Abstract

Objectives

Recent preclinical studies suggest that treating glioblastoma (GBM) with a combination of targeted chemotherapy and radiotherapy may enhance the anti-tumor effects of both therapies. However, the effects of these treatments on glioma growth and progression are poorly understood.

Methods

In this study we have tested the effects of combination therapy in a mouse glioma model that utilizes a PDGF-IRES-Cre-expressing retrovirus to infect adult glial progenitors in mice carrying conditional deletions of Pten and p53. This model produces tumors with the histological features of GBM with 100% penetrance, making it a powerful system to test novel treatments. Sunitinib is an orally active, small molecule inhibitor of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) critical for tumor growth and angiogenesis, including PDGF receptors. We investigate the addition of Sunitinib to radiotherapy, and use bioluminescence imaging to characterize the effects of treatment on glioma growth and progression.

Results

Treating our PDGF-driven mouse model with either Sunitinib or high-dose radiation alone delayed tumor growth and had a modest but significant effect on survival, while treating with low-dose radiation alone failed to control glioma growth and progression. The addition of Sunitinib to low-dose radiation caused a modest, but significant delay in tumor growth. However, no significant survival benefit was seen as tumors progressed in 100% of animals. Histological analysis revealed a reduction in vascular proliferation and a marked increase in brain invasion. An additional study combining Sunitinib with high-dose radiation revealed a fatal toxicity despite individual monotherapies being well tolerated.

Discussion

These results show that the addition of Sunitinib to radiotherapy fails to significantly alter survival in GBM despite enhancement of the effects of radiation. Furthermore, an enhanced risk of toxicity associated with combined therapy must be considered in the design of future clinical studies.

Keywords: glioblastoma, PDGF, radiation, radiotherapy, sunitinib, sutent, SU1128, VEGF

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and most aggressive primary malignant brain tumor [1]. Despite advancements in GBM therapy, the prognosis for patients undergoing standard treatment remains approximately 14 months [2]. Ionizing radiation is a critical component of standard therapy for GBM in addition to surgical resection and chemotherapy. However, GBMs are highly radioresistant and tumors invariably recur. Novel therapies that target mechanisms of radioresistance in GBM may enhance cure rates and offer a better-tolerated alternative to systemic chemotherapies.

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and their ligands have been implicated in radioresistance and may offer important therapeutic targets for tumor radiosensitization [3–5]. Radiation has been shown to upregulate RTKs, including VEGF and PDGF receptors, with clear roles in tumor angiogenesis, endothelial cell survival, and tumor cell proliferation [6–12]. Within the tumor, a release of these “pro-survival” signals in response to radiation may contribute to radioresistance. Thus, modulation of RTK signaling might decrease radioresistance and enhance the clinical benefits of radiation. A variety of preclinical studies have shown that radiotherapy, combined with the blockade of VEGF and PDGF receptors, augments the anti-tumor effects of the individual therapies [9, 13–31]. However, the effects of these therapies on glioma growth and progression remain poorly understood. In addition, it is unclear how such combined therapies should be administered.

Sunitinib is an orally active, small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of renal cell-carcinoma (RCC), imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) [32, 33], and progressive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [34]. Sunitinib selectively inhibits various RTKs critical for tumor growth and angiogenesis, including VEGF and PDGF receptors [27, 35–37]. While Sunitinib monotherapy is insufficient to adequately suppress GBM progression [38], there are data to suggest that the addition of Sunitinib to radiotherapy may be a promising treatment strategy for GBM [39]. However, to date no study has combined Sunitinib with radiation in an intracranial model of GBM.

Our lab has generated a murine model of GBM that uses a PDGF-IRES-Cre expressing retrovirus to infect adult glial progenitors in mice carrying conditional deletions of Pten and p53 [40]. This model produces brain tumors with the histological features of GBM with 100% penetrance and provides a useful model system in which to test novel therapies. We investigated the effects of the addition of Sunitinib to radiotherapy on tumor growth, progression, and survival using this model. We demonstrated that while Sunitinib and high-dose radiation were well tolerated individually and delayed tumor growth effectively to extend survival, the combination of Sunitinib with high-dose radiation resulted in a dose-dependent, fatal toxicity. Furthermore, we showed that while low-dose radiation alone failed to alter tumor growth significantly, the combination of Sunitinib with low-dose radiation delayed tumor growth, but did not have a significant effect on survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor formation

Primary tumors were induced in the subcortical white matter of transgenic mice carrying conditional deletions of Pten and p53 and stop-floxed luciferase protein using a PDGF-IRES-Cre retrovirus as described previously [40]. Malignant glioma cells were then isolated from virus-induced primary tumors as described previously [40]. Anesthetized mice underwent stereotactic injection of isolated glioma cells (1.5 × 104 cells or 2.0 × 104 cells) into the subcortical white matter (stereotactic coordinates relative to bregma: 2 mm anterior, 2 mm lateral, 2 mm deep) using a Hamilton syringe with a 33-gauge needle (1.5 µl at 0.4 µl/min). All animal work was performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines of Columbia University.

Sunitinib and vehicle formulation

Sunitinib (SU11248 or sutent, Pfizer, New York, USA) solution was prepared weekly for oral gavage. The solution composition was: Sunitinib 0.0125–0.5%, Hydrochloric acid (HCl, used as 5N solution) 1 to 1.02 molar ratio of Sunitinib, polysorbate 80 0.5%, polyethylene glycol 300 10%, sodium hydroxide (0.1N solution) to pH ~ 3.3 – 3.7, in distilled water to 100%. An identical vehicle solution without Sunitinib was used as control. Mice receiving Sunitinib (60 mg/kg) or vehicle solution were gavaged daily on a five-day-on/two-day-off treatment cycle (5/2 schedule) until the end of the study.

Radiation

Mice were anesthetized daily with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine and fractionated radiotherapy was delivered using a Mark 1 Cesium-137 irradiator (JL Shepherd and Associates) at a dose rate of 0.7138 min/Gy. Body shielding was used to ensure selective irradiation of the head. Radiation was delivered as low-dose 2 Gy fractions over 30 days (2 Gy/day, 5/2 schedule), or high-dose 6 Gy fractions over 10 days (6 Gy/day, 5/2 schedule), to either a maximum dose of 60 Gy or until the initial onset of symptoms. Low-dose hypofractionated radiation was chosen to reflect standard fractionated doses used in human GBM [41]. High-dose hypofractionated radiation was designed to facilitate the complete administration of 60 Gy within the rapid course of our tumor model.

Survival Studies

Adult transgenic mice carrying a conditional deletion of PTEN and p53 and stop-floxed luciferase protein were injected with primary tumor cells as described above. Tumor growth was monitored three times weekly with bioluminescence imaging (see below). Treatment was initiated 6–9 days post injection (dpi) to allow time for measurable tumor growth to occur. In one study, treatment was initiated at 17 dpi in an attempt to better characterize the effects of treatment initiation on a larger initial tumor burden. To ensure comparable tumor size between treatment groups, animals were sequentially sorted into treatment groups in order of descending bioluminescence signal on the day of treatment initiation. In animals receiving Sunitinib in addition to radiotherapy, radiation was administered at least 30 minutes (min) after administration of Sunitinib to allow for systemic delivery of the drug. Animals were monitored daily for signs or symptoms related to tumor burden such as weight loss, seizures, posturing, and nasal and/or periorbital hemorrhage. In accordance with IACUC guidelines, animals were euthanized at the first sign of morbidity and brains were harvested.

Bioluminescence imaging

Bioluminescence imaging using an IVIS Imaging System 100 Series (Xenogen, Alameda, Ca) was used to monitor tumor burden three times weekly beginning 6 days post injection. Bioluminescence imaging determines emitted light as a measure of the relative number of viable tumor cells in the tumor and correlates with tumor burden (data not shown). Briefly, 100 µL of D-luciferin (3 mg/mL, Gold Biotechnology, USA) in sterile PBS was administered via intra-peritoneal injection. Twenty minutes later, animals were imaged at a distance of 25 cm from the light detector. Bioluminescence was recorded as the number of photons per minute (photons/min) in a region of interest (ROI) placed selectively around the mouse’s head. Images were analyzed using Living Image software, version 2.50 (Xenogen).

Toxicity studies

Non-tumor bearing mice of the same strain used in the survival studies were placed in groups and selected to receive one of eight different treatment schedules. Schedules tested included: combined Sunitinib and high-dose radiotherapy [S+R]; combined Sunitinib and high-dose radiotherapy following two days of Sunitinib pre-treatment [S, (S+R)]; high-dose radiotherapy administered alone following two days of Sunitinib pre-treatment [S, R]; high-dose radiotherapy followed by daily Sunitinib maintenance [R, S’]; Sunitinib pre-treatment sequentially followed by high-dose radiotherapy alone and subsequent daily Sunitinib maintenance [S, R, S’]; high-dose radiation alone [R]; Sunitinib combined with low-dose radiotherapy and subsequent daily Sunitinib maintenance (2 Gy/day, 20 Gy, [(S+r), S’]). Animals were monitored daily for signs or symptoms related to treatment-associated toxicities. All animals surviving 14 days after the end of their respective treatment schedule were considered to have survived therapy.

Histological Analysis

All animals underwent intracardiac perfusion with 15 mL ice cold PBS, followed by 15 mL cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) prior to tissue harvesting. Brains were removed and fixed overnight at 4 degrees in 4% PFA. Tumor tissue was paraffin embedded, microtome sectioned (5 µm sections) and processed for hematoxylin and eosin stains.

Statistical Analysis

Survival analysis was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method with logrank test. Mean bioluminescence between two groups underwent Mann Whitney non-parametric analysis, and Kruskal-Wallis analysis was performed in situations with greater than two groups. All statistical analysis was performed using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

High-dose radiation delays tumor growth and prolongs survival

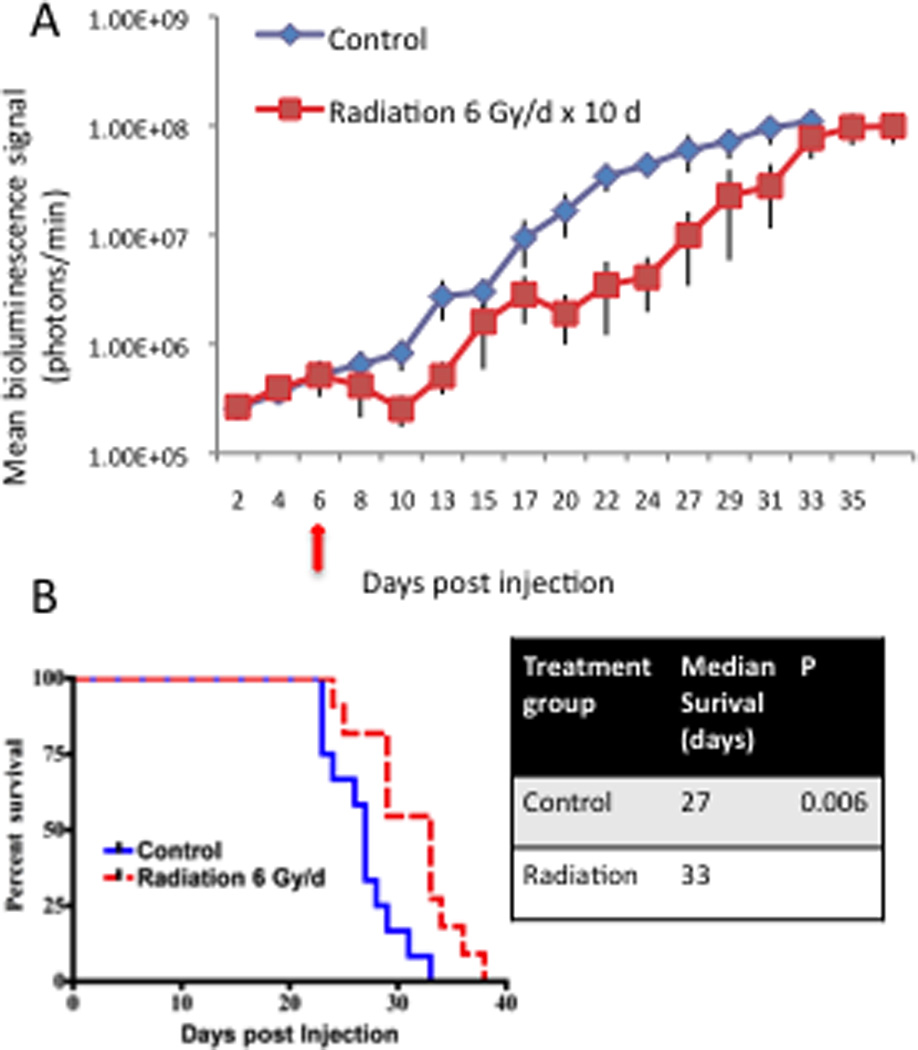

To establish an effective radiation dose and measure its effects on tumor growth and progression, tumors were induced by cell injection (2.0 × 104 cells). At 6 dpi, mean tumor burden was measured and animals were sequentially sorted in order of descending bioluminescence signal to receive either high-dose radiation (6 Gy/day, 5/2 schedule; n = 12), or to serve as controls (n = 12) and not receive radiation. High-dose radiation effectively delayed tumor growth as measured by bioluminescence imaging (Fig 1A). Radiation-induced tumor growth delay resulted in a statistically significant increase in median overall survival from 27 days to 33 days (p = 0.006, Fig 1B). Despite therapy, all animals eventually succumbed to tumor-induced morbidity.

Figure 1. High-dose radiation delays tumor growth and prolongs survival.

(A) Plot of tumor growth rates in control animals (blue line) and animals receiving high-dose radiation (6 Gy × 10 days, 5/2 schedule) selectively to the head (red line). Treatment was initiated at 6 dpi (red arrow). Each line shows the changes in the mean value of the luciferase signal from each group. Bars show the S.E.M at each time point. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the survival of control mice vs. mice receiving high-dose radiation. High-dose radiation significantly extended median survival to 33 dpi from 27 dpi in controls. The p value for the comparison is shown in the right panel.

The addition of Sunitinib to high-dose radiotherapy results in fatal toxicity

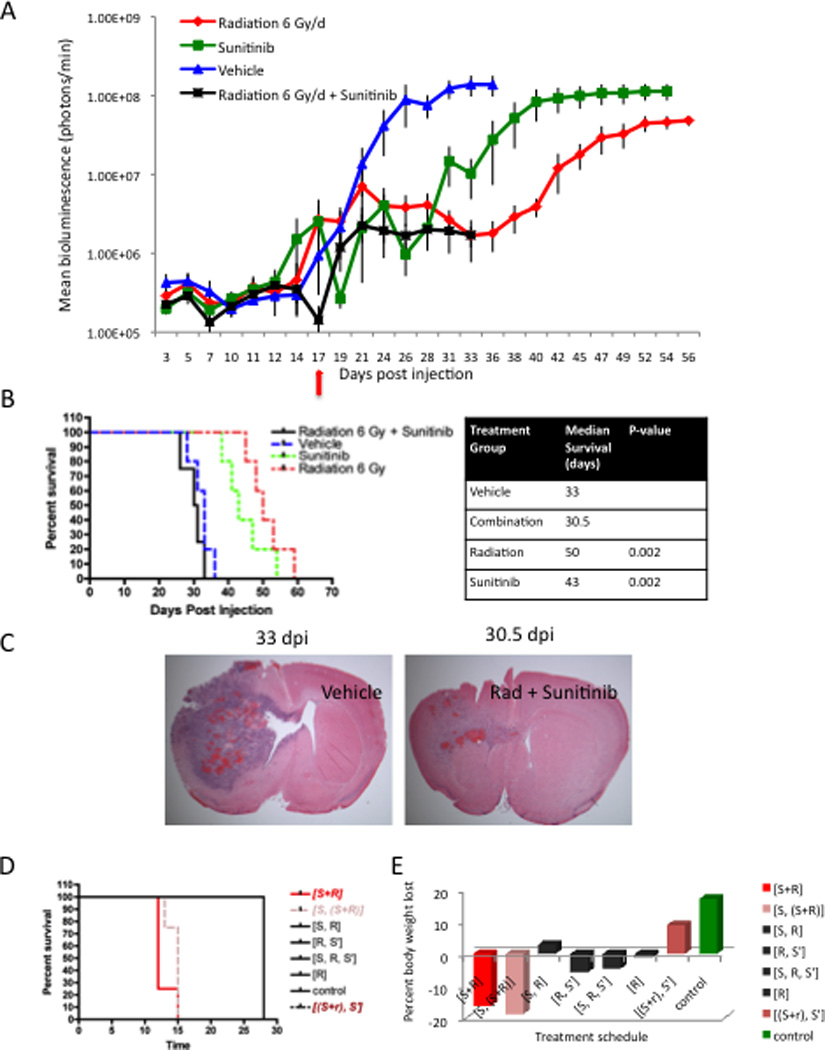

To test whether the addition of Sunitinib to high-dose radiotherapy enhanced the anti-tumor effects of either therapy alone, tumors were induced by cell injection (1.5 × 104 cells) as described above. At 17 dpi, mean tumor burden was recorded and animals were sequentially sorted in order of descending bioluminescence signal into groups as described above. Individual groups received one of four treatments: Sunitinib monotherapy (60 mg/kg, 5/2 schedule; n = 5), high-dose fractionated radiation (6-Gy/day, 5/2 schedule; n = 5), combined administration of Sunitinib and high-dose radiation (n = 5) followed by daily Sunitinib maintenance until the end of the study, or a vehicle solution identical to the Sunitinib solution without the addition of Sunitinib. In addition, animals receiving combination therapy were pretreated for two days with Sunitinib prior to the initiation of radiation.

Sunitinib and high-dose radiation were individually well tolerated and capable of delaying tumor growth compared with a vehicle solution (Fig 2A). Median overall survival was increased from 33 days in animals receiving vehicle solution to 43 days and 50 days with Sunitinib and radiation monotherapies, respectively (p = 0.002, Fig 2B). However, animals succumbed to large morbidity-inducing tumors suggesting that tumors had adapted and progressed despite treatment.

Figure 2. The addition of Sunitinib to high-dose radiotherapy results in fatal toxicity.

(A) Plot depicting tumor growth rates in our 4 experimental treatment groups. Treatment was initiated at 17 dpi (red arrow). Each line shows the changes in the mean value of the luciferase signal from each group. Bars show S.E.M at each time point. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the survival of our 4 experimental groups. Sunitinib (green line) or high-dose radiation (red line) alone extended median survival from 33 dpi in vehicle treated mice (blue line) to 43 dpi and 50 dpi, respectively. Animals receiving combination therapy developed early signs/symptoms of morbidity and were euthanized reducing median overall survival to 30.5 dpi. The p values for significant comparisons are shown in the right panel. (C) Low powered micrographs confirm tumor growth delay at similar time points after injection and initiation of treatment by showing H&E stains of tumors in mice that received vehicle solution or combination therapy and were sacrificed for evidence of morbidity (D) Kaplan-Meier curves comparing survival of tumor-naïve mice receiving one of eight treatment schedules: combined Sunitinib and high-dose radiotherapy [S+R]; combined Sunitinib and high-dose radiotherapy following two days of Sunitinib pre-treatment [S, (S+R)]; high-dose radiotherapy administered alone following two days of Sunitinib pre-treatment [S, R]; high-dose radiotherapy followed by Sunitinib maintenance [R, S’]; Sunitinib pre-treatment sequentially followed by high-dose radiotherapy alone and subsequent Sunitinib maintenance [S, R, S’]; high-dose radiation [R]; Sunitinib combined with low-dose radiotherapy and subsequent Sunitinib maintenance (2 Gy/day, 20 Gy, [(S+r), S’]). All mice receiving [S, (S+R)] and [S+R] showed evidence of morbidity and were euthanized reducing their median survival to 13 dpi and 14 dpi, respectively. All other treatment schedules were well tolerated with mice surviving until the study’s end. (E) Bar graphs showing mean percent body weight lost during treatment. Mice receiving [S+R] lost an average of 16% of their overall body weight. Mice receiving [S, (S+R)] lost an average of 19% of their overall body weight.

Of note, 100% of animals receiving combination therapy were sacrificed early due to signs of treatment-associated toxicity and thus, a significant survival advantage could not be assessed. Symptoms included: weight loss, posturing, poor grooming and immobility. Early sacrifice reduced the median overall survival of animals receiving combination therapy to 30.5 days versus 33 days in vehicle-treated mice (Fig 2B). Bioluminescence imaging revealed that the addition of Sunitinib to high-dose radiation effectively delayed tumor growth compared with vehicle solution or Sunitinib alone (Fig 2A). Tumor burden at the onset of morbidity was significantly smaller than in time-matched vehicle-treated animals supporting a non-tumor-related cause of morbidity (vehicle 1.38 × 108 ± 4.08 × 107 photons/min, combination 1.70 × 106 ± 9.33 × 105 photons/min, p = 0.009). Reduced tumor burden was confirmed by histological analysis (Fig 2C). Of note, no qualitative evidence of hemorrhage, robust inflammation, or frank necrosis was seen to suggest a mechanism of toxicity. Thus, while the addition of Sunitinib to high-dose radiation effectively delayed tumor growth, the occurrence of fatal treatment-associated toxicities revealed a therapeutic limit to combination therapy.

Treatment-induced toxicity suggests a therapeutic limit to combination therapy

To confirm toxicity with the concurrent administration Sunitinib and high-dose radiation, control, un-injected, tumor-naïve mice (n = 35) were subjected to a variety of treatment schedules as described above. Sunitinib and high-dose radiation were well tolerated when administered individually or in sequence (Fig 2D). However, all mice receiving Sunitinib and high-dose radiation concurrently ([S+R]; [S, (S+R)]) developed signs of general toxicity identified by weakness, posturing, poor grooming, immobility, and an average loss of 16%–19% of body weight by the end of 2 dosing schedules (Fig 2D,E). Of note, the addition of Sunitinib to low-dose radiation (2-Gy/day, 5/2 schedule, [(S+r), S’]) was well tolerated and all animals survived treatment (Fig 2D,E). Thus, we confirmed that the addition of Sunitinib to high-dose radiation resulted in a fatal toxicity that was not evident with either monotherapy alone or in sequence. In addition, these studies revealed that Sunitinib could be combined safely with low-dose radiation.

The combination of Sunitinib and low-dose radiotherapy has modest effects on tumor growth, but no significant effect on survival

To characterize the effects of the addition of Sunitinib to low-dose radiation, tumors were induced in mice by cell injection (2.0 × 104 cells) as described above. At 9 dpi, animals were sorted into treatment groups. We performed three survival studies using a single primary tumor-derived cell line.

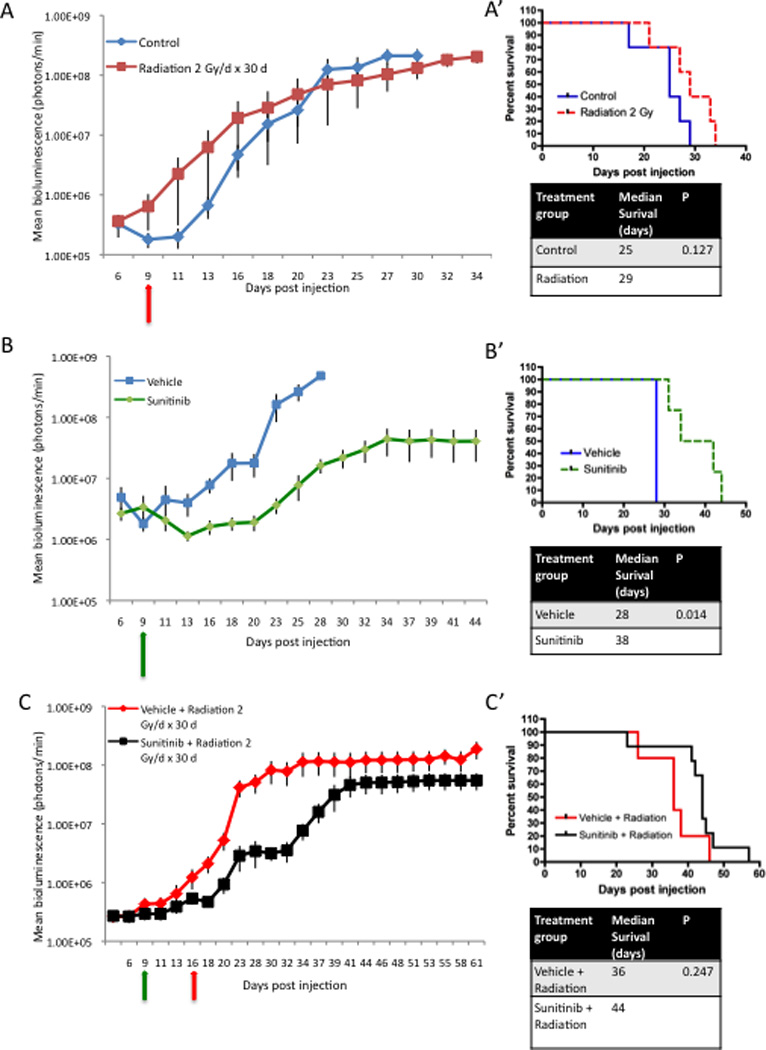

To characterize the effects of low-dose radiation (2 Gy/day, 5/2 schedule) in our model, animals were sorted to serve as controls (n = 5) or to receive low-dose radiation (n = 5). Treatment attenuated tumor growth slightly as measured by bioluminescence imaging (Fig 3A). Tumor growth delay failed to significantly increase median overall survival (25 days vs. 29 days; p = 0.127; Fig 3A’). Thus, while low-dose radiation was well tolerated in our model, it failed to show therapeutic benefit.

Figure 3. Low-dose radiation attenuates tumor growth without survival benefits.

(A) Plot of tumor growth rates in control animals (blue line) and animals receiving low-dose radiation (2 Gy × 30 days, 5/2 schedule) selectively to the head (red line). Treatment was initiated at 9 dpi (red arrow). Each line shows the changes in the mean value of the luciferase signal from 5 mice per group. Bars show the S.E.M at each time point. (A’) Kaplan-Meier curves show that low-dose radiation insignificantly increases survival from 25 dpi to 29 dpi compared with controls. The p value is in the right panel. (B) Plot of tumor growth rates vehicle solution (blue line) or Sunitinib (green line) treated animals. Treatment was initiated at 9 dpi (green arrow). (B’) Kaplan-Meier curves showing that Sunitinib significantly increased median survival from 28 dpi to 38 dpi, as compared with a vehicle solution. The p value is shown in the right panel. (C) Plot of tumor growth rates in animals from our combined treatment groups. Treatment was initiated at 9 dpi (green arrow) with either a vehicle solution (n = 4) or Sunitinib therapy (n = 7). Low-dose radiation was initiated at 16 dpi (red arrow). (C’) Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrate the addition of Sunitinib vs. a vehicle solution to low-dose radiation extended survival from 36 dpi to 44 dpi. The survival difference was not significant. The p value for the comparison is shown in the right panel.

To confirm the efficacy of Sunitinib, groups began treatment with either Sunitinib (60 mg/kg, 5/2 schedule) or a vehicle solution (5/2 schedule). Consistent with previous data, Sunitinib effectively delayed tumor growth and resulted in a statistically significant increase in median overall survival from 28 days to 38 days (p = 0.014; Fig 3B,B’).

To investigate the efficacy of the combination of Sunitinib and low-dose radiotherapy, groups began treatment with either Sunitinib (60 mg/kg, 5/2 schedule; n = 9) or a vehicle solution (5/2 schedule; n = 6). In a variation on previous experiments, low-dose radiation (2 Gy/day, 5/2 schedule) was initiated after one week of treatment with either Sunitinib or vehicle solution (16 dpi). Each animal was scheduled to receive a total dose of 60 Gy in combination with Sunitinib or vehicle solution followed by Sunitinib or vehicle maintenance therapy until the end of the survival study. The addition of Sunitinib to low-dose radiation delayed tumor growth as compared with the combination of radiation and a vehicle solution (Fig 3C). Tumor growth delay increased the median overall survival from 36 days in the radiation and vehicle group to 44 days in the radiation and Sunitinib group. However, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.247; Fig 3C’). Suntinib and radiation increased overall survival from 38 days to 44 days compared to Sunitinib monotherapy. However, this also failed to reach significance (p = 0.106).

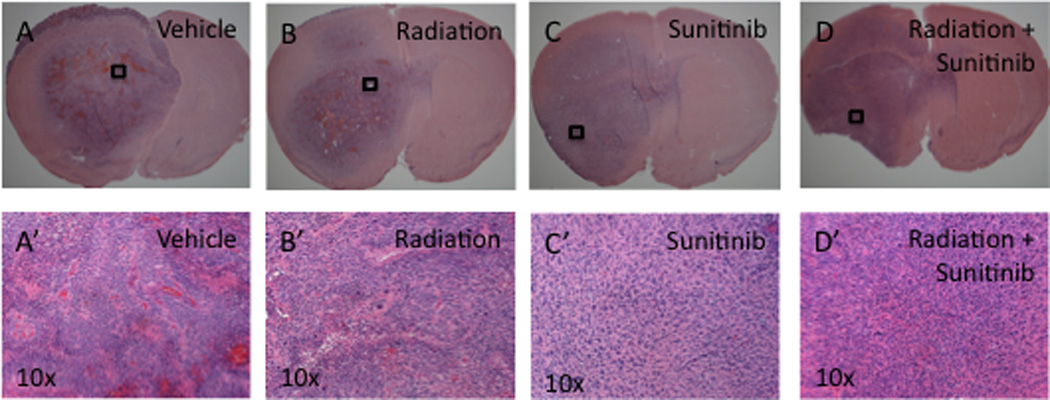

Sunitinib alone or in combination with radiation results in morphologically distinct tumors

Despite therapy, large morbidity-inducing brain tumors developed in 100% of animals suggesting that tumors were adapting to therapy (Fig 4). Postmortem analysis of all animals demonstrated tumor growth primarily in the subcortical white matter ipsilateral to the injection site. Consistent with published work in this model [40], untreated and vehicle-treated controls developed tumors with the histological features of human GBM on H&E including: diffuse parenchymal infiltration, marked vascular proliferation, and pseudopalisading necrosis (Fig 4A, A’). Tumors treated with both high-dose and low-dose radiotherapy resembled vehicle-treated tumors on H&E with the addition of increased nuclear pleomorphism and an abundance of multinucleated cells (Fig 4B, B’).

Figure 4. Sunitinib alone or in combination with radiation results in morphologically distinct tumors.

(A–D) Low and (A’–D’) high powered (10×) micrographs showing H&E stains of end stage tumors from mice in our 4 treatment groups. (A, A’) Tumors formed in mice receiving vehicle solution show histological features of GBM, including areas of pseudopalisading necrosis. (B, B’) Tumors formed in mice receiving low-dose radiation show evidence of radiation damage such as multinucleated giant cells, in addition to the histological features of GBM. (C, C’) Tumors formed in mice receiving Sunitinib alone or (D, D’) in combination with low-dose radiation showed altered morphology represented by diffuse infiltration, a delicate vascular pattern, perineuronal satellitosis, and a notable absence of necrosis.

In contrast, whether administered alone or in combination with radiotherapy, Sunitinib altered tumor morphology as seen on H&E (Fig 4C, C’, D, D’). Qualitative analysis of these lesions confirmed previous findings in our model [42]. Histological analysis demonstrated a greater and more diffuse level of infiltration, a delicate vascular pattern, perineuronal satellitosis, and a notable absence of necrosis. Tumors subjected to combination therapy demonstrated the histological characteristics of Sunitinib-treated tumors with the addition of increased nuclear pleomorphism and multinucleated cells characteristic of radiation therapy (Fig 4D, D’). Thus, Sunitinib therapy was sufficient to cause a consistent change in tumor morphology, suggesting an adaptive response of the tumor to therapy.

DISCUSSION

Radiation remains a critical component of GBM therapy. However, GBM is characteristically radioresistant and despite initial responses to treatment, tumors invariably recur. To date, adjunctive systemic chemotherapies have added little to overall survival in the setting of GBM and are associated with a variety of poorly tolerated side effects [2]. Targeted chemotherapy may offer a promising new GBM treatment strategy. Several previous studies suggested that targeted inhibitors of PDGF and VEGF signaling associated with tumor angiogenesis and survival are well tolerated and may enhance the cure rates of ionizing radiation [7, 22, 39, 43]. However, these studies looked mainly at xenograft glioma models that may not accurately recapitulate the natural tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, multiple-drug regimens have been used to achieve inhibition of multiple RTKs. The current study addresses the addition of the receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor Sunitinib to radiation in an in vivo intracranial model of GBM. Our results show that Sunitinib enhances the effects of low-dose radiation on tumor growth delay without effects on overall survival as tumors rapidly adapt and progress despite therapy. We also show that the addition of Sunitinib to a higher dose of radiation results in a fatal toxicity despite the safe and effective administration of the individual therapies, suggesting a therapeutic limit to combination therapy.

While monotherapy with either Sunitinib or high-dose radiation was well tolerated and capable of controlling GBM, combined therapy created a fatal toxicity in both tumor-bearing and tumor-naïve mice. This is the first study to identify negative effects with this combination. Preclinical investigations of Sunitinib in combination with radiation, performed in hind-limb xenograft models of GBM, failed to reveal significant negative side effects [39]. However, hind-limb xenograft models of GBM do not address the effects of cytotoxic therapies on normal brain structures. In one study examining orthotopic human GBM cell-line xenografts (U251-NG2), radiation after anti-VEGF treatment was well tolerated and effective at reducing tumor progression [44]. In this study combination therapy was delivered over a six-week period by brachytherapy that permitted high-dose irradiation of the tumor (21.5 Gy) with lower dosing of the adjacent normal mouse tissue (8 Gy). Furthermore, PDGF signaling was not inhibited which is different from our study.

The mechanism by which combination therapy produced negative side effects remains unclear. Clinical trials combining the VEGF inhibitor Bevacizumab with Temozolomide during and after radiation have generally reported only mild side effects, including a small risk of cerebral and GI hemorrhage [45–47]. However, these studies report a relatively frequent occurrence of cerebral ischemia and it has been proposed that combination therapy may potentiate a radiation-induced occlusive arteriopathy [45]. In the current study, we failed to see gross evidence of hemorrhage, inflammation or frank necrosis in tumors treated with the combination of Sunitinib and high-dose radiation. This implies that the toxic effects of combined therapy have a more subtle mechanism of action. Sunitinib may enhance the cytotoxic effects of radiation on surrounding brain or block signaling pathways affecting the repair of normal brain injured by radiation. It is also possible that combination therapy potentiates negative effects on other susceptible tissues within the area of irradiation, such as the pharynx, esophagus, or trachea, and that negative effects on these tissues caused or contributed to the negative effects of therapy. Further investigation is needed to determine if either of these factors contributed to morbidity and mortality in our cohort. Importantly, as clinical trials investigating the addition of Sunitinib to radiotherapy have been proposed, the possibility that combination therapy may elicit toxic side effects must be considered in the design of these trials.

We used bioluminescence imaging to characterize the effects of therapy on tumor growth. Our results demonstrate that administration of either high-dose radiation or Sunitinib attenuated tumor growth while administration of low-dose radiation failed to significantly alter tumor progression. The addition of Sunitinib to high-dose radiation did show evidence of effective tumor growth delay on bioluminescence imaging and histology. However, the therapeutic effects were limited due to the toxicity in all animals receiving combined therapy. Interestingly, the addition of Sunitinib to low-dose radiation enhanced tumor growth delay as compared with radiation alone. In future studies it will be important to determine if the effects of combined therapy are additive or synergistic, and if these effects can be optimized, within the limits conferred by toxicity, to provide a significant improvement in survival.

This is the first report to address the effects of combination therapy with Sunitinib and radiation on overall survival in an intracranial model of GBM. The addition of Sunitinib to low-dose radiation failed to increase overall survival despite evidence of increased tumor growth delay. In a recent phase II study, patients treated with the anti-VEGF antibody Bevacizumab in combination with Temozolomide during and after radiation therapy showed improved progression-free survival without improvement in overall survival [45]. Delayed tumor growth without an associated increase in overall survival could still hold clinical significance as progression-free survival influences patient quality of life. Furthermore, compared with systemic chemotherapies currently employed in GBM therapy, Sunitinib is well tolerated with few side effects. Therefore, Sunitinib may offer a safe and effective adjuvant to standard therapies.

Progression in spite of radiation therapy may be due to any number of the proposed mechanisms of radioresistance [10, 48]. In our study, histological analysis of tumors treated with either Sunitinib alone or in combination with radiotherapy showed phenotypic changes associated with progression in the setting of therapy. It is possible that additional RTK signaling pathways are upregulated in the setting of VEGFR and PDGFR blockade. Furthermore, a tumor’s specific molecular signature may be an important indicator of treatment response [40, 49]. In future studies, better understanding the mechanisms of tumor progression will guide us in glioma patient selection and therapy design.

CONCLUSION

These results show that the addition of Sunitinib to radiotherapy enhances the effects of radiation in the brain and delays GBM growth without altering overall survival at the studied doses. Additional studies are needed to better understand benefits and limitations combination therapy, as well as to identify the mechanisms by which gliomas evolve and evade therapy. Furthermore, a risk of toxic side effects with combined therapy must be considered in the design of future clinical studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This project was supported by NIH/NINDS (grant no. PC-R01NS066955-01). A special thanks to Richard Leung, Benjamin Amendolara, Mike Castelli, Simon Hanft, MD, and Jason Ellis, MD for their support and expertise.

References

- 1.CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous Sytem Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2004–2006. Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hovinga KE, et al. Radiation-enhanced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion in glioblastoma multiforme cell lines--a clue to radioresistance? J Neurooncol. 2005;74(2):99–103. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-4204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaifer CA, Huang J, Lin PC. Glioblastoma cells incorporate into tumor vasculature and contribute to vascular radioresistance. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(9):2063–2075. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li HF, Kim JS, Waldman T. Radiation-induced Akt activation modulates radioresistance in human glioblastoma cells. Radiat Oncol. 2009;4:43. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lerman OZ, et al. Low-dose radiation augments vasculogenesis signaling through HIF-1-dependent and -independent SDF-1 induction. Blood. 2010;116(18):3669–3676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorski DH, et al. Blockage of the vascular endothelial growth factor stress response increases the antitumor effects of ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1999;59(14):3374–3378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund EL, et al. Differential regulation of VEGF, HIF1alpha and angiopoietin-1, -2 and-4 by hypoxia and ionizing radiation in human glioblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(6):833–838. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timke C, et al. Combination of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor/platelet-derived growth factor receptor inhibition markedly improves radiation tumor therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(7):2210–2219. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown CK, et al. Glioblastoma cells block radiation-induced programmed cell death of endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;565(1–3):167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner HH, et al. Autocrine pathways of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in glioblastoma multiforme: clinical relevance of radiation-induced increase of VEGF levels. J Neurooncol. 2004;66(1–2):129–138. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000013495.08168.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori K, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase, ERK1/2, is essential for the induction of vascular endothelial growth factor by ionizing radiation mediated by activator protein-1 in human glioblastoma cells. Free Radic Res. 2000;33(2):157–166. doi: 10.1080/10715760000300711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li M, et al. Small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor signaling (SU9518) modifies radiation response in fibroblasts and endothelial cells. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CG, et al. Anti-Vascular endothelial growth factor treatment augments tumor radiation response under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. Cancer Res. 2000;60(19):5565–5570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachsberger P, Burd R, Dicker AP. Improving tumor response to radiotherapy by targeting angiogenesis signaling pathways. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2004;18(5):1039–1057. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Reilly MS. Radiation combined with antiangiogenic and antivascular agents. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2006;16(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siemann DW, et al. Differentiation and definition of vascular-targeted therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(2 Pt 1):416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan LW, Camphausen K. Angiogenic tumor markers, antiangiogenic agents and radiation therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2003;3(3):357–366. doi: 10.1586/14737140.3.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teicher BA, et al. Antiangiogenic treatment (TNP-470/minocycline) increases tissue levels of anticancer drugs in mice bearing Lewis lung carcinoma. Oncol Res. 1995;7(5):237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdollahi A, et al. SU5416 and SU6668 attenuate the angiogenic effects of radiation-induced tumor cell growth factor production and amplify the direct anti-endothelial action of radiation in vitro. Cancer Res. 2003;63(13):3755–3763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachsberger PR, et al. Effect of the tumor vascular-damaging agent, ZD6126, on the radioresponse of U87 glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(2 Pt 1):835–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ning S, et al. The antiangiogenic agents SU5416 and SU6668 increase the antitumor effects of fractionated irradiation. Radiat Res. 2002;157(1):45–51. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)157[0045:taasas]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin RJ, et al. Simultaneous inhibition of the receptor kinase activity of vascular endothelial, fibroblast, and platelet-derived growth factors suppresses tumor growth and enhances tumor radiation response. Cancer Res. 2002;62(6):1702–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu B, et al. Broad spectrum receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, SU6668, sensitizes radiation via targeting survival pathway of vascular endothelium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58(3):844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zips D, et al. Enhanced susceptibility of irradiated tumor vessels to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2005;65(12):5374–5379. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards E, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling in the response of vascular endothelium to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 2002;62(16):4671–4677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wachsberger P, Burd R, Dicker AP. Tumor response to ionizing radiation combined with antiangiogenesis or vascular targeting agents: exploring mechanisms of interaction. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(6):1957–1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oertel S, et al. Human glioblastoma and carcinoma xenograft tumors treated by combined radiation and imatinib (Gleevec) Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;182(7):400–407. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergers G, et al. Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(9):1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saharinen P, Alitalo K. Double target for tumor mass destruction. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(9):1277–1280. doi: 10.1172/JCI18539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erber R, et al. Combined inhibition of VEGF and PDGF signaling enforces tumor vessel regression by interfering with pericyte-mediated endothelial cell survival mechanisms. FASEB J. 2004;18(2):338–340. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0271fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodman VL, et al. Approval summary: sunitinib for the treatment of imatinib refractory or intolerant gastrointestinal stromal tumors and advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(5):1367–1373. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rock EP, et al. Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary: Sunitinib malate for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor and advanced renal cell carcinoma. Oncologist. 2007;12(1):107–113. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raymond E, et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):501–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendel DB, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(1):327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mena AC, Pulido EG, Guillen-Ponce C. Understanding the molecular-based mechanism of action of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor: sunitinib. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21(Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000361534.44052.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Folkman J. Angiogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neyns B, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib malate in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2011;103(3):491–501. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schueneman AJ, et al. SU11248 maintenance therapy prevents tumor regrowth after fractionated irradiation of murine tumor models. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):4009–4016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lei L, et al. Glioblastoma Models Reveal the Connection between Adult Glial Progenitors and the Proneural Phenotype. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker MD, Strike TA, Sheline GE. An analysis of dose-effect relationship in the radiotherapy of malignant gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5(10):1725–1731. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(79)90553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sisti J. "Abstract 323. Treating a PDGF-Driven Model of Glioblastoma with Sunitinib Slows Tumor Growth and Prolongs Survival But Induces a Marked Increase in Tumor Cell Invasion" Abstracts from the 2009 Joint Meeting of the Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons (AANS/CNS) Section on Tumors: October 22–24, 2009: New Orleans, LA. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(5):564–699. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geng L, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling leads to reversal of tumor resistance to radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61(6):2413–2419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verhoeff JJ, et al. Tumour control by whole brain irradiation of anti-VEGF-treated mice bearing intracerebral glioma. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(17):3074–3080. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai A, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab plus temozolomide during and after radiation therapy for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(2):142–148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vredenburgh JJ, et al. Addition of Bevacizumab to Standard Radiation Therapy and Daily Temozolomide Is Associated with Minimal Toxicity in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gutin PH, et al. Safety and efficacy of bevacizumab with hypofractionated stereotactic irradiation for recurrent malignant gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(1):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang JE, et al. Radiotherapy and radiosensitizers in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2007;5(11):894–902. 907–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chahal M, et al. MGMT modulates glioblastoma angiogenesis and response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(8):822–833. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]