Abstract

Purpose

T1 quantification of contrast agents, such as super-paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles, is a challenging but important task inherent to many in vivo applications in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In this work, a sweep imaging with Fourier transformation using variable flip angles (VFA-SWIFT) method was proposed to measure T1 of aqueous SPIO nanoparticle suspensions.

Methods

T1 values of various iron concentrations (from 1 to 7 mM) were measured using VFA-SWIFT and three-dimensional (3D) spoiled gradient-recalled echo with variable flip angles (VFA-SPGR) sequences on a 7T MR scanner. For validation, T1 values were also measured using a spectroscopic inversion-recovery (IR) sequence on a 7T spectrometer.

Results

VFA-SWIFT demonstrated its advantage for quantifying T1 of highly concentrated aqueous SPIO nanoparticle suspensions, but VFA-SPGR failed at the higher end of iron concentrations. Both VFA-SWIFT and VFA-SPGR yielded linear relationships between the relaxation rate and iron concentrations, with relaxivities of 1.006 and 1.051 s−1•mM−1 at 7T, respectively, in excellent agreement with the spectroscopic measurement of 1.019 s−1•mM−1.

Conclusion

VFA-SWIFT is able to achieve accurate T1 quantification of aqueous SPIO nanoparticle suspensions up to 7 mM.

Keywords: T1 mapping, super-paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles, sweep imaging with Fourier transformation (SWIFT), positive contrast

Introduction

Super-paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles have been widely used as T2 or contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Various applications including visualization of vasculature, macrophage uptake, and cell labeling have been demonstrated (1–3). Recently studies demonstrated that SPIO nanoparticles could be applied to hyperthermia treatment of cancer (4,5). However, as the SPIO concentration increases, MR signal loss and image distortions become more prominent in the regions near the SPIO nanoparticles.

In recent years, ultra-short echo time (UTE) (6,7) and sweep imaging with Fourier transformation (SWIFT) (8,9) sequences have been designed to shorten the time interval between signal excitation and acquisition, down to several microseconds. Therefore, short signal loss can be minimized. For example, the UTE sequence was applied to visualize short materials (10). The T1 estimation of low concentrations (up to 1.2 mM) of SPIO nanoparticles was conducted by using the UTE sequence (11). Springer et al. assessed T1 values in materials and tissues (e.g. cortical bones) with extremely fast signal decay using the UTE sequence combined with a variable flip angle method (12).

Similarly, the SWIFT sequence was implemented for detection of calcifications in rat brain and SPIO-labeled stem cells grafted in the myocardium (13,14). Recently Chamberlain et al. proposed a Look-Locker saturation recovery method integrated with SWIFT to measure T1 with an adiabatic half passage followed by a spoiler gradient to achieve saturation (15). Despite the breakdown of the linear relationship at ultra high concentrations (above 1 mg Fe/mL), they demonstrated that SWIFT could be used to measure T1 at iron concentrations (0.3–1.5 mg Fe/mL) previously almost impossible by MRI.

With SWIFT, the signal is measured in the steady state; thus, image contrast can be optimized by properly adjusting the flip angle close to the Ernst angle, the ideal condition at which the signal intensity reaches its peak for a given T1 (8,16). The spoiled steady state nature of the SWIFT technique provides an opportunity to derive a T1 map through measurements conducted with variable flip angles (VFA). In many in vivo applications of SPIO nanoparticles, such as cell tracking and therapeutic response evaluation, the iron concentration is at low or medium levels. In this work we hypothesize that the VFA-SWIFT sequence is able to measure T1 of ferrofluids, consisting of SPIO nanoparticle solutions with higher range of iron concentrations than usually encountered (from 1 to 7 mM).

When attempting to measure T1 using VFA methods, an ambiguous solution for T1 can sometimes result when using an inhomogeneous radiofrequency field B1 for excitation. To overcome this difficulty, we utilize a birdcage coil that provides a better B1 field homogeneity (i.e., more uniform spin excitation and reception) compared to a surface coil. In addition, we use a scheme of small step-size, multiple flip angles for accuracy of estimation. For the purpose of comparison, T1 values were also quantified using the three-dimensional (3D) spoiled gradient-recalled echo at variable flip angles (VFA-SPGR) sequence. In order to verify the obtained results, relaxation data were also acquired with a spectroscopic inversion recovery (IR) sequence and resulting T1 values are compared with those measured by VFA-SWIFT and VFA-SPGR.

Theory

For a general steady state MR scan, the signal intensity is theoretically given by (16):

| (1) |

where , and M0 and θ represent proton density and flip angle, respectively. With fixed TE and TR, T1 can be measured through scans at multiple flip angles (16,17):

| (2) |

The terms E1 and can be numerically solved as the slope and coordinate intercept of Eq. (2) through a linear least-squares fit, and T1 can then be estimated from the natural logarithm of E1 (17). However, for materials with short values, the signal intensity, S(θ), given by Eq. (1) will decay exponentially and result in a poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) when TE is close to or longer than , which could dramatically influence the accuracy of the derived T1 using Eq. (2).

For the SWIFT sequence, the magnetic field variation resulting from the applied gradient field is generally large compared to other potential perturbations, such as magnetic field inhomogeneity and magnetic susceptibility differences, and these effects are minimal in acquired images (8) due to the simultaneous high bandwidth excitation and acquisition. Additionally, SWIFT images are minimally influenced by transverse relaxation, since the dead time between signal excitation and acquisition is usually much shorter than values (8). Under these circumstances, a region of interest (ROI) in a SWIFT image is immune to signal loss due to values of the scanned subject if signal pileup artifacts are included in the ROI (14). This leads to independent signal intensity for the ROI in the following form (8):

| (3) |

Therefore, VFA-SWIFT provides a method for T1 estimation that can ignore the influence of signal loss caused by the fast decay and allow for quantification of ferrofluid with high iron concentrations.

Methods

Data Acquisition

Commercially available ferrofuild (EMG 509, FerroTec, Santa Clara, CA) was diluted into seven different iron concentrations: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 mM Fe, where 1 mM Fe is about 0.056 mg Fe/mL. The diluted ferrofluid was then filled into plastic vials (0.3 mL in volume). All vials together with a vial of purified water (labeled as 0) were then embedded into a rectangular container, which was filled with 1% agar gel. The MR experiment was performed on a 7 Tesla Varian Magnex small animal scanner (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) that provides a maximum gradient strength of 440 mT/m. The phantom was vertically placed in the center of a transmit/receive birdcage coil with a diameter of 7.2 cm.

First, 3D radial SWIFT images were obtained using a hyperbolic secant pulse with the dimensionless shape factor n = 1 and truncation factor β = 7.6, respectively (8,9). The pulse had a spectral width (sw) of 62.5 kHz and included 256 gaps. The length of the pulse elements and gaps were 4 and 12 μs, respectively. The dead time between the end of each pulse element and the beginning of signal acquisition was set to 3.9 μs, referred to as the effective TE. Complex data in the radial k-space consisted of 64,000 spokes, which covered a spherical field-of-view (FOV) of 803 mm3. The repetition time (TR) was equal to 6 ms, including a 1.9 ms-interval between two sequential hyperbolic secant pulses. Before actual data acquisition, 512 dummy scans were implemented to generate a steady state. Multiple flip angles, from 4° to 36° with a step size of 2°, were applied for T1 estimation.

Next, for comparison purposes, a general steady state scan of the phantom was performed using a 3D SPGR sequence. To minimize signal loss caused by the decay, the shortest TE achievable for the 7T scanner was selected. The scan parameters were: TE/TR = 2.95/6 ms, sw = 62.5 kHz, FOV = 803 mm3, matrix size = 2563, and 512 dummy scans were performed to reach a steady state. Both RF and gradient spoils were implemented to enhance the T1 weighted contrast and eliminate any residual signal. As in the SWIFT scan, the flip angles were varied from 4° to 36° with a step size of 2°.

In order to verify the estimated T1 values derived by the MRI-based approaches, spectroscopic data were acquired using a vertical 7T Varian NMR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). An inversion-recovery (IR) pulse sequence was implemented, and the IR delays (TI) were varied from 10 ms to 690 ms with an increment of 20 ms for vials 1 to 7. Between two IR scans, a 3 s time interval was inserted after the data acquisition to allow a full recovery of the magnetization.

Furthermore, in order to estimate how T2 influences the flip angles of SWIFT, T2 of the highest iron concentration solution (vial 7) was measured using a Carr-Purcell Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) sequence on the 7T spectrometer, with 40 different TE values varied uniformly from 0.1 to 4 ms, and with TR ≈ 1 s.

Data Processing

The k-space data of the SWIFT sequence were processed using signal processing and gridding code (http://www.cmrr.umn.edu/swift/) written in LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin, TX) and interpolated with a Kaiser-Bessel function onto a Cartesian grid (18) utilizing compiled Matlab mex code (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Complex images were then obtained by using the Fourier transforms of the 3D k-space data in a Cartesian coordinate frame.

Least-square fits were implemented based on Eqs. (2) and (3) for every voxel of the VFA-SWIFT images to derive the T1 map of different concentrations of aqueous SPIO nanoparticle suspensions. As a comparison, the T1 map was also calculated using the 3D SPGR images at different flip angles. For the spectroscopic IR data, T1 values of the vials 1 to 7 were obtained by fitting Eq. (4):

| (4) |

where A is a scaling factor. To minimize errors, the largest measurable T1 for the ferrofluid was cut off at 2.5 s in this work. T1 mapping and data fitting codes were implemented in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

T2 of the vial 7 was obtained using the spectroscopic CPMG data by fitting Eq. (5):

| (5) |

For SWIFT and SPGR, the average SNR of vial 7 was derived experimentally by dividing the mean signal intensity inside the vial by the noise standard deviation.

Results

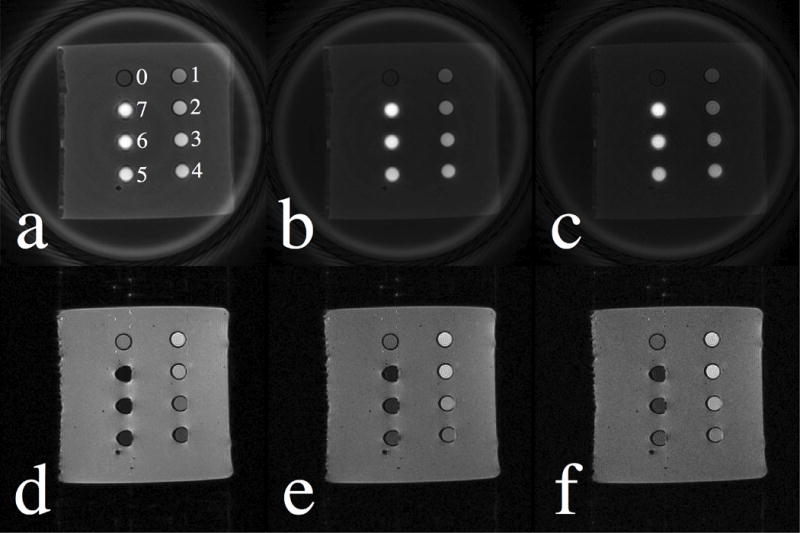

Fig. 1 displays the magnitude images acquired with SWIFT (1st row) and SPGR (2nd row) sequences at flip angles of 10° (1st column), 20° (2nd column), and 30° (3rd column). Vials with different iron concentrations were labeled in Fig. 1(a), where vial 0 only contained purified water and vials 1 through 7 corresponded to iron concentrations ranging from 1 to 7 mM (see Table 1 for details). As shown for the SWIFT images, signal intensity of the water and agar gel decayed as the flip angle increased. The vials with higher concentrations of SPIO nanoparticles appeared brighter than those with lower concentrations. As can be seen in Fig. 1(a), line-broadening and off-resonance artifacts become more apparent as the concentration increases beyond 5 mM (vials 5 through 7). In the SPGR images, signal from background agar gel was also decreased at larger flip angles, similar to that seen in the SWIFT images. However, for vials containing more than 3 mM iron (vial 3 through 7), decay becomes strong and dominant with SPGR, resulting in significant signal loss, image distortions, and negative contrast. Conversely, the SWIFT sequence provided positive contrast for the SPIO nanoparticle solutions.

Figure 1.

SWIFT and SPGR images acquired at flip angles of 10° (1st column), 20° (2nd column), and 30° (3rd column) are illustrated in the first and second row, respectively. In Fig. 1(a), vials with purified water and different iron concentrations are labeled from 0 to 7 (see the Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

Iron concentrations (1 mM Fe is approximately 0.056 mg Fe/mL) of the different vials are listed in the second column. The T1 values estimated by the VFA-SWIFT, VFA-SPGR and spectroscopic IR based methods are presented in the last three columns.

| Vial Numbers | Concentrations [mM] | Estimated T1 Values [ms] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| VFA-SWIFT | VFA-SPGR | IR | ||

| 1 | 1 | 733.2 ± 29 | 679.9 ± 26 | 714.7 |

| 2 | 2 | 446.7 ± 23 | 412.4 ± 24 | 435.4 |

| 3 | 3 | 296.5 ± 18 | 289.6 ± 17 | 306.7 |

| 4 | 4 | 212.9 ± 12 | 233.8 ± 18 | 242.1 |

| 5 | 5 | 183.1 ± 15 | 167.8 ± 21 | 183.2 |

| 6 | 6 | 153.1 ± 13 | − | 152.2 |

| 7 | 7 | 137.8 ± 14 | − | 132.9 |

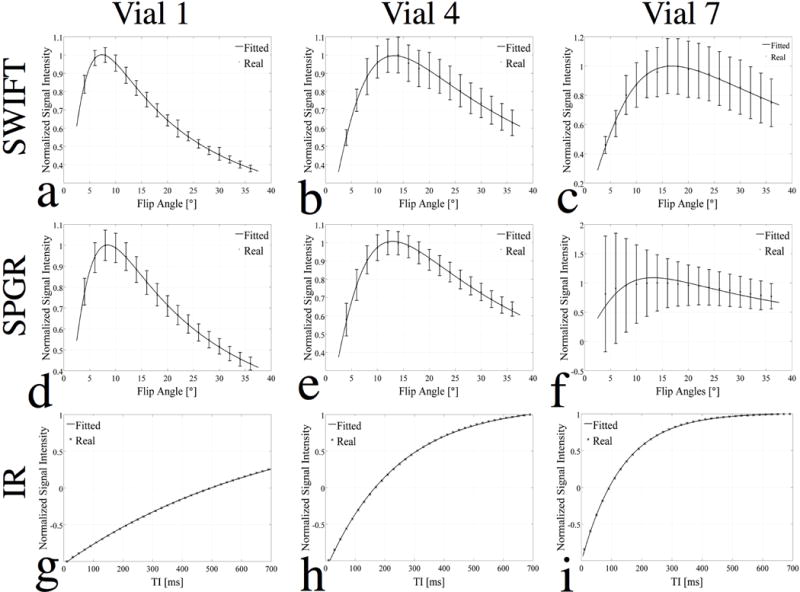

Further analyses of these imaging data are shown in Fig. 2. The plots show the normalized (with respect to its maximum value) and averaged signal intensity of vials 1, 4, and 7 (representing a low, medium, and high concentration) as a function of flip angles for the VFA-SWIFT (1st row) and VFA-SPGR (2nd row), and as a function of TI for the spectroscopic measurement (3rd row). A linear least-squares fitting was done first using Eq. (2) to estimate the slope and coordinate intercept, and then the two quantities were plugged back into Eq. (1) for SPGR and Eq. (3) for SWIFT to re-plot the signal intensity (shown as the solid line) as a function of flip angles. Along with the increment in iron concentration, the standard deviation (shown as error bars) increased accordingly. The Ernst angle for vials 1, 4, and 7 were at approximately 7°, 13° and 17°; thus, the corresponding signal peak at the Ernst angle could be observed in Figs. 2(a–e). However, the iron concentration in vial 7 was so high that the signal was degraded significantly because of the fast decay for the SPGR images, resulting a flatter plot than that of vials 1 and 4 and large error bars. Thus, Fig. 2(f) failed to match the fitting curve because the signal at different flip angles was contaminated by noise. As shown in Figs. 2(g–i), the spectroscopic IR data were well fitted to Eq. (4). The signal null points, which were decreased as the iron concentrations increased, were noticed at TI of 500, 170 and 90 ms for vials 1, 4, and 7, respectively.

Figure 2.

Plots of normalized signal intensity (averaged within each vial) of vials 1 (1st column), 4 (2nd column) and 7 (3rd column), representing a low, medium, and high concentration, as a function of flip angles for SWIFT (1st row) and SPGR (2nd row), and of inverse recovery decays (TI) for spectroscopic IR method (3rd row). For the SWIFT and SPGR studies, the flip angle was fitted to the normalized signal using Eqs. (1–3). For the spectroscopic IR method, TI was fitted to the normalized signal using Eq. (4).

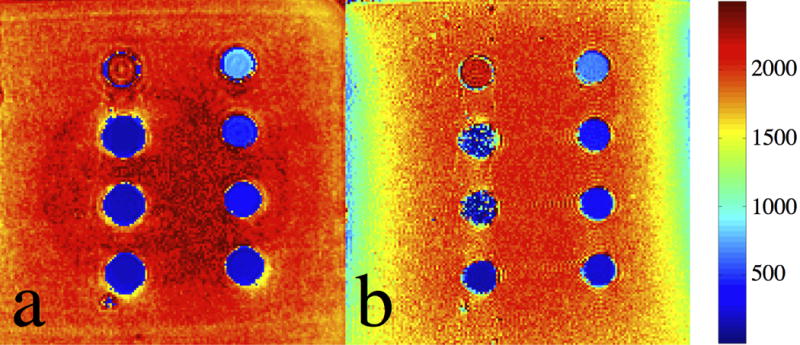

Fig. 3 shows the estimated T1 maps resulting from the (a) VFA-SWIFT and (b) VFA-SPGR acquisitions. According to the figure, both sequences resulted in a good T1 estimation when concentrations were lower than 5 mM (vial 0 through 5). T1 of ferrofluid in vials 6 and 7 could only be obtained from Fig. 3(a), but not from Fig. 3(b). This indicates that the SWIFT sequence is more suitable for measuring T1 of ferrofluid at high concentrations, compared to the 3D SPGR sequence. As seen from the two T1 maps, T1 was decreased and the line-broadening and off-resonance artifacts become significant along with the increase of concentrations. Furthermore, two shaded regions can be observed at both the left and right sides of Fig. 3(b), indicating the estimated T1 of agar gels at these regions was influenced by the magnetic field inhomogeneity.

Figure 3.

T1 maps of the SPIO phantom estimated by using the (a) VFA-SWIFT and (b) VFA-SPGR based approaches. The unit of the color bar is in [ms].

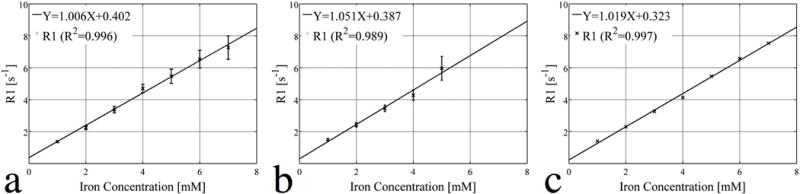

Figs. 4(a–c) present the linear fitting of the relaxation rate R1 to the various iron concentrations for the VFA-SWIFT, VFA-SPGR, and spectroscopic based methods. Fig. 4(a) shows that a linear relationship between R1 and the iron concentration is valid for all concentrations up to 7 mM. According to the fit, the specific relaxivity (r1) of the ferrofluid was 1.006 s−1•mM−1 under a 7T magnetic field. Fig. 4(b) presents a similar fit as that of Fig. 4(a), but without considering the last two data points (not shown) due to the significant signal loss caused by the effect. By using the first five data points, the resulting relaxivity was equal to 1.051 s−1•mM−1. In Fig. 4(c), a nearly perfect linear fitting is shown and the relaxivity derived by the spectroscopic IR approach was equal to 1.019 s−1•mM−1. The corresponding R2 values were 0.996, 0.989 and 0.997 for Figs. 4(a–c), respectively. However, for the VFA-SPGR result in the Fig. 4(b), standard deviations of the estimated R1 increased significantly at 5 mM compared to that at low concentrations and the corresponding SWIFT result.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of the different vials are linearly fitted to their R1 values estimated by the (a) VFA-SWIFT, (b) VFA-SPGR and (c) spectroscopic IR based methods. Notice that data from vials 6 and 7 were not included in the fitting due to the signal loss caused by fast T2* decay. The r1 values (slope) of the fits in (a), (b) and (c) are equal to 1.006, 1.051, and 1.019 s−1•mM−1. The R2 values of the three fits are equal to 0.996, 0.989 and 0.997.

Table 1 summarizes the quantitative T1 estimates for the various iron concentrations using the VFA-SWIFT, VFA-SPGR, and spectroscopic methods. The first two columns list the vial numbers and their iron concentrations, while the estimated T1 are given in the last three columns. Note that the VFA-SPGR method was unable to estimate T1 for high iron concentrations. Additionally, standard deviations of the T1 values measured by VFA-SWIFT are slightly smaller than that measured by VFA-SPGR, especially at higher concentrations. The highest concentration at which the VFA-SPGR method can reliably measure T1 is about 5 mM. By comparing with the spectroscopic measurements, it can be seen that both VFA-SWIFT and VFA-SPGR provide accurate estimates of T1 when the iron concentration is in the low to medium range, but only VFA-SWIFT reliably measures T1 at high iron concentrations.

Based on Eq. 5, the estimated T2 of the vial 7 is about 1.04 ms by fitting data acquired at all the echo times in the CPMG measurement. For the vial 7, the averaged experimental SNR of the SWIFT images is about 3–5 times bigger than that of the SPGR images.

Discussion

In the past, T1 estimation of highly concentrated ferrofluid has usually suffered from signal loss caused by the rapid decay. This study presents the VFA-SWIFT method to map T1 of aqueous suspensions containing SPIO contrast agents, along with comparisons with two other common approaches: VFA-SPGR and spectroscopic IR. Here, the SWIFT sequence was applied to scan the SPIO sample vials using multiple flip angles. Since the dead time between the signal excitation and acquisition is shortened to 3.9 μs, signal loss caused by decay is minimized. Consequently, the signal intensity is dependent on proton density, flip angle, T1, and TR values. Furthermore, the vials filled with ferrofluid displayed T1-weighted positive contrast, where the SNR of these vials was higher than that of the agar gel alone in the SWIFT images (Fig. 1). Since decay has minimal influence on the SWIFT images, the theoretical model (Eq. (3)) for T1 measurement and the experimental data agreed reasonably well (as seen in Figs. 2(a–c)). As a result, relatively small error bars were obtained for the estimated R1 values of ferrofluid even at high concentrations (as shown in Fig. 4(a)).

Measurements obtained with VFA-SPGR and spectroscopic IR methods were compared with those measured by VFA-SWIFT. In the SPGR sequence, a minimally allowed TE of 2.95 ms was utilized, aiming to minimize signal loss caused by high iron concentration. By using this short TE, MR signals resulting from SPIO concentrations up to 4 mM (vial 4) were still comparable to the background signal of agar gel (as shown in the 2nd row of Fig. 1). Based on the SPGR images, we were able to measure the T1 of the first five vials (with concentrations up to 5 mM), although the standard deviations increased with concentration (as shown in the Fig. 4(b)). However, compared to the VFA-SWIFT, this method was more susceptible to signal loss. The spectroscopic IR measurement was used as a reference in this work, and it demonstrated that VFA-SWIFT and VFA-SPGR allowed accurate estimations of T1 for ferrofluid at iron concentrations up to 7 and 5 mM, respectively.

SWIFT has demonstrated advantages over SPGR in detecting materials with short values. However, with the modest acquisition bandwidth (62.5 kHz) used in the present SWIFT experiments, it was not possible to entirely eliminate influences from the strong magnetic field inhomogeneity caused by SPIO nanoparticles. The 3D Fourier transform of the T2 decay in time results in a blurring function in the image space, as line-broadening and off-resonance artifacts appeared in the area surrounding the vials of high iron concentrations (19). Additionally, with the same noise standard deviation, the relative SNR ratio of SWIFT and SPGR can be estimated by the ratio of Eqs. (3) and (1) with the consideration of the receiver duty cycles, or explicitly , where Tacq is the total acquisition time. Although both sequences had the same acquisition bandwidth, the gaps in the SWIFT pulse introduce a 50% deduction of Tacq in this work. Furthermore, only half of the acquired data points (128) were used for image reconstruction in SWIFT, introducing an additional 50% deduction of Tacq. Hence, the theoretically estimated ratio of SNRs of SWIFT and SPGR should approximate to , which is slightly higher than the experimental ratio.

Furthermore, with the currently used acquisition bandwidth, the flip angle will be smaller than the expected value when T2 is extremely short due to significant decay during the pulse. With VFA-SWIFT, this effect would result in greater T1 error as the SPIO concentration increases. However, depending on the excitation bandwidth and T2 value, this error may be mitigated (9,20). An excitation performance could be estimated by the coefficient (9). The largest effect will occur with vial 7, which has the shortest T2 (1.04 ms) among all the vials. However, with the RF bandwidth used in this work (62.5 kHz), the coefficient is equal to 0.998, implying that the effect of T2 could be ignored during the RF transmission of SWIFT in this work. Therefore, despite these potential sources of error, this study clearly demonstrates that the proposed VFA-SWIFT method is valid for iron concentrations up to 7 mM at 7T, when the flip angles are selected to be between 4° to 36°.

According to Figs. 4(a) and 4(c), T1 changes proportionally with the iron concentration up to 7 mM. This suggests that iron quantification, from low to high concentrations, can be performed using our proposed method. This is potentially crucial for cell labeling, cell tracking, and hyperthermia treatment of cancer when using SPIO nanoparticles. In addition, due to the unique image contrast, T1 maps of short materials (such as cortical bone and teeth) might eventually be utilized in clinical diagnoses.

It was recently reported that the Look-Locker saturation recovery method was combined with SWIFT to measure T1 of ferrofluid at ultra high concentrations (15). Additionally, the UTE sequence is another approach that can shorten the effective TE down to a few microseconds, allowing for T1 measurement of short materials (11,12). The difference between SWIFT and UTE is that in SWIFT encoding gradients are always on, whereas in 3D UTE a hard pulse is used to excite signal first and then the gradient is ramped on. Due to this difference, in the presence of short T2* that is comparable with the ramping time, UTE images are expected to be more blurry (19). Recently, a continuous SWIFT was designed to eliminate the T2* decay even more than the current version of SWIFT (21). An MR approach with zero echo time (ZTE) was achieved to measure short T2 samples (e.g. human teeth) and yielded detailed depictions with very good delineation of the mineralized dentin and enamel layers (22). However, comparisons with UTE, ZTE, and continuous SWIFT on T1 mapping are beyond the scope of this work.

In conclusion, a VFA-SWIFT sequence was implemented to successfully quantify T1 of SPIO nanoparticle solutions up to 7 mM. The result was compared with the T1 values derived by VFA-SPGR and spectroscopic IR approaches. Although the VFA-SPGR sequence failed to estimate the T1 at high concentrations, both VFA-SWIFT and VFA-SPGR presented good linear relationships between the relaxation rate R1 and iron concentrations, with relaxivities of approximately 1.006 and 1.051 s−1•mM−1 at 7T, which is close to the spectroscopic IR result of 1.019 s−1•mM−1. The proposed method in this work is potentially useful for quantification of low to high concentrations of SPIO nanoparticles for in vivo MRI applications.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the following grants: NIH P41RR008079, P41EB015894, R21CA139688, KL2RR033182, and S10RR023706 from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. In addition we thank Dr. John Glushka and Dr. Khan Hekmatyar for MR data acquisition, Brian Hanna and Michael Tesch for continued collaboration in development of the SWIFT package.

References

- 1.Cromer Berman SM, Kshitiz, Wang CJ, Orukari I, Levchenko A, Bulte JW, Walczak P. Cell motility of neural stem cells is reduced after SPIO-labeling, which is mitigated after exocytosis. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;69(1):255–262. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards JM, Shaw CA, Lang NN, Williams MC, Semple SI, Macgillivray TJ, Gray C, Crawford JH, Alam SR, Atkinson AP, Forrest EK, Bienek C, Mills NL, Burdess A, Dhaliwal K, Simpson AJ, Wallace WA, Hill AT, Roddie PH, McKillop G, Connolly TA, Feuerstein GZ, Barclay GR, Turner ML, Newby DE. In vivo mononuclear cell tracking using superparamagnetic particles of iron oxide: feasibility and safety in humans. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2012;5(4):509–517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.972596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramaswamy S, Schornack PA, Smelko AG, Boronyak SM, Ivanova J, Mayer JE, Jr, Sacks MS. Superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) labeling efficiency and subsequent MRI tracking of native cell populations pertinent to pulmonary heart valve tissue engineering studies. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(3):410–417. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gneveckow U, Jordan A, Scholz R, Bruss V, Waldofner N, Ricke J, Feussner A, Hildebrandt B, Rau B, Wust P. Description and characterization of the novel hyperthermia- and thermoablation-system MFH 300F for clinical magnetic fluid hyperthermia. Medical physics. 2004;31(6):1444–1451. doi: 10.1118/1.1748629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Q, Wang L, Cheng R, Mao L, Arnold RD, Howerth EW, Chen ZG, Platt S. Magnetic nanoparticle-based hyperthermia for head & neck cancer in mouse models. Theranostics. 2012;2:113–121. doi: 10.7150/thno.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyler DJ, Robson MD, Henkelman RM, Young IR, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance imaging with ultrashort TE (UTE) PULSE sequences: technical considerations. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2007;25(2):279–289. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robson MD, Gatehouse PD, Bydder M, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance: an introduction to ultrashort TE (UTE) imaging. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2003;27(6):825–846. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Park JY, Garwood M. Fast and quiet MRI using a swept radiofrequency. J Magn Reson. 2006;181(2):342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Moeller S, Garwood M. Gapped pulses for frequency-swept MRI. J Magn Reson. 2008;193(2):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goto H, Fujii M, Iwama Y, Aoyama N, Ohno Y, Sugimura K. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of articular cartilage of the knee using ultrashort echo time (uTE) sequences with spiral acquisition. J Med Imag Radiat On. 2012;56(3):318–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2012.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang LJ, Zhong XD, Wang LY, Chen HW, Wang YA, Yeh JL, Yang L, Mao H. T1 Weighted Ultrashort Echo Time Method for Positive Contrast Imaging of Magnetic Nanoparticles and Cancer Cells Bound With the Targeted Nanoparticles. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2011;33(1):194–202. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springer F, Steidle G, Martirosian P, Syha R, Claussen CD, Schick F. Rapid Assessment of Longitudinal Relaxation Time in Materials and Tissues With Extremely Fast Signal Decay Using UTE Sequences and the Variable Flip Angle Method. Invest Radiol. 2011;46(10):610–617. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31821c44cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehto LJ, Sierra A, Corum CA, Zhang J, Idiyatullin D, Pitkanen A, Garwood M, Grohn O. Detection of calcifications in vivo and ex vivo after brain injury in rat using SWIFT. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou R, Idiyatullin D, Moeller S, Corum C, Zhang H, Qiao H, Zhong J, Garwood M. SWIFT detection of SPIO-labeled stem cells grafted in the myocardium. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;63(5):1154–1161. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamberlain R, Etheridge M, Idiyatullin D, Corum C, Bischof J, Garwood M. Measuring T1 in the presence of very high iron concentrations with SWIFT. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haacke EM. Magnetic resonance imaging : physical principles and sequence design. New York: J. Wiley & Sons; 1999. p. xxvii.p. 914. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treier R, Steingoetter A, Fried M, Schwizer W, Boesiger P. Optimized and combined T1 and B1 mapping technique for fast and accurate T1 quantification in contrast-enhanced abdominal MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;57(3):568–576. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson JI, Meyer CH, Nishimura DG, Macovski A. Selection of a Convolution Function for Fourier Inversion Using Gridding. Ieee T Med Imaging. 1991;10(3):473–478. doi: 10.1109/42.97598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahmer J, Bornert P, Groen J, Bos C. Three-dimensional radial ultrashort echo-time imaging with T2 adapted sampling. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;55(5):1075–1082. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson PE, Gurney PT, Nayak K, Gold GE, Pauly JM, Nishimura DG. Designing long T2 suppression pulses for ultrashort echo time imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;56(1):94–103. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idiyatullin D, Suddarth S, Corum CA, Adriany G, Garwood M. Continuous SWIFT. J Magn Reson. 2012;220:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiger M, Pruessmann KP, Bracher AK, Kohler S, Lehmann V, Wolfram U, Hennel F, Rasche V. High-resolution ZTE imaging of human teeth. NMR Biomed. 2012;25(10):1144–1151. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]