Abstract

Objectives

Depressive symptoms and physical inactivity are health risks among minority older adults. This study examined whether social support moderated the relationship of depressive symptoms to walking behavior among 217 community-dwelling, Hispanic older adults.

Method

Cross-sectional analyses were used to test whether different forms of social support interacted with depressive symptoms to affect both likelihood and amount of walking.

Results

Analyses showed a significant interaction between depressive symptoms and instrumental support related to the likelihood of walking and a marginally significant interaction between depressive symptoms and instrumental social support related to the amount of walking. Depressive symptoms were associated with a lower likelihood and lower amount of walking among participants receiving high levels of instrumental social support (e.g., help with chores) but not low instrumental support. Emotional and informational support did not moderate the depression to walking relationship.

Conclusion

Receiving too much instrumental support was related to sedentary behavior among depressed older adults.

Keywords: older adults, Hispanics/Latinos, depressive symptoms, walking, social support

Depressive symptoms have been associated with low levels of physical activity in various populations, including older adults (Dunn, Trivedi, & O'Neal, 2001; Krause, Goldenhar, Liang, Jay, & Maeda, 1993; Kritz-Silverstein, Barrett-Connor, & Corbeau, 2001; Morgan & Bath, 1998). Symptoms of depression, such as diminished interest in activities and fatigue, can in and of themselves interfere with activities of daily living and physical activity (e.g., Crane, 2005; Machado, Gignac, & Badley, 2008; Nguyen, Koepsell, Unutzer, Larson, & LoGerfo, 2008; Satariano, Haight, & Tager, 2000). However, there may be other mechanisms by which depressive symptoms influence physical activity. A better understanding of these mechanisms may help promote physical activity, a health behavior related to many positive health outcomes including positive quality of life (Bassuk & Manson, 2005; Bath & Morgan, 1998; Hirvensalo, Rantanen, & Heikkinen, 2000; Nelson et al., 2007; Reynolds, Haley, & Kozlenko, 2008; Taylor et al., 2004).

Social support is a factor that may prevent depressive symptoms from leading to a sedentary lifestyle, promoting healthy behaviors, mental and physical health. Existing research shows that certain forms of social support may protect individuals from depressive symptoms (Barnett & Gotlib, 1988; Dean, Kolody, & Wood, 1990; Lu, 1999), high blood pressure (Uchino, Cacioppo, & Keicolt-Glaser, 1996), metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease, among other health problems (Horsten, Mittleman, Wamala, Schenck-Gustaffson, & Orth-Gomer, 1999; Smith & Ruiz, 2002). There is evidence that social relationships may influence health outcomes through their impact on neouroendocrine and immune functioning, among other physiological mechanisms (see Seeman, 2000; Uchino, 2006). Social support may also improve health by encouraging healthy behaviors, such as physical activity (Stahl et al., 2001). Indeed, family and other members in one's own social network can monitor and exert pressure on individuals to behave in healthier ways (Tucker, 2002; Umberson, 1987). Having someone provide support and encouragement to exercise has been found to increase exercise (Oka, King, & Young, 1995). Similarly, receiving support to exercise in the form of an exercise partner or friends/family members who exercise regularly can also improve physical activity (Booth, Owen, Bauman, Clavisi, & Leslie, 2000; Shores, West, Theriault, & Davison, 2009).

More general forms of social support—in other words, support not specifically directed toward encouraging physical activity—have also been related to physical activity, although not in a consistent manner. In a cross-sectional study of adults aged 20 to 79, Fischer Aggarwal, Liao, and Mosca (2008) found that both emotional and instrumental support (e.g., receiving help with chores) were associated with more physical activity. Conversely, Kaplan, Lazarus, Cohen, and Leu (1991) reported that social isolation and being unmarried (a possible indicator of lower social support) were related to physical inactivity 9 years later in the Alameda County study. In a study of 50- to 68-year-olds, Hawkley, Thisted, and Cacioppo (2009) found that loneliness, which tapped into a person's satisfaction with his or her social network, was related to a higher likelihood of physical inactivity over 3 years. However, the literature is unclear regarding how different forms of social support influence physical activity, specifically among older adults with depressive symptoms.

Among the complexities of this type of research is that social support has multiple dimensions and that not all have had consistent or even positive effects on health and well-being (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001; Krause & Rook, 2003; Newsom & Schulz, 1998; Seeman, 2000; Uchino, 2009). A distinction has been made between the structural aspects of social support, which include group membership, network size, and frequency of contact, versus the functional aspects of social support, which encompass the type of support received, such as emotional, informational, or instrumental support (see Cohen & Wills, 1985).

Cohen and Wills (1985) further clarified certain complexities of this research by proposing two theoretical models to explain how social support might influence health. The stress-buffering model suggests that social connections are most beneficial when individuals are distressed, whereas the main effects model suggests that social connections are beneficial whether the person is distressed or not. Some have found that structural aspects of social support (e.g., integration within a social network) may have a more direct effect on health as posited by the main effects model, whereas functional aspects of social support (e.g., emotional support) may be more likely to buffer the impact of distress by promoting better coping strategies (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001).

Building on these theoretical models and existing research, this article examines the role of social support as a possible mechanism by which depressive symptoms are related to walking in a sample of Hispanic older adults. The main research question asks whether the relationship of depressive symptoms to walking differs depending on whether older adults experience different forms of functional social support. Specifically, analyses investigate whether emotional, instrumental, informational, and overall functional social support interact with depressive symptoms to affect the likelihood and amount of walking. Given the inconsistent findings from previous studies, results of this study are expected to fill a gap in the literature by providing additional information on the ways in which depressive symptoms, social support, and walking are related to one another among older adults. In particular, analyses may help explain whether functional social support (i.e., emotional, informational, or instrumental support) might buffer the effects of depressive symptoms on walking. This is a particularly important research question for vulnerable subgroups of U.S. older adults, including Hispanic older adults and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES), who tend to have high rates of both depressive symptoms (Black, Markides, & Miller, 1998; Falcón & Tucker, 2000; Mendes de Leon, Rapp, & Kasl, 1994) and physical inactivity (Crespo, Ainsworth, Keteyian, Heath, & Smit, 1999; Marquez, McAuley, & Overman, 2004). Previous findings with this sample of Hispanic older adults show high levels of depressive symptoms, comparable with or higher than other population-based samples of U.S. Hispanic older adults (Perrino, Mason, Brown, & Szapocznik, 2009). A strength of this study is its focus on walking behavior, the most common and accessible form of physical activity among older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999). Given the challenging factors involved in effectively preventing and managing depressive symptoms and physical inactivity among older adults (see Fiske, Wetherell, & Gatz, 2009; King, Rejeski, & Buchner, 1998), identifying other potential mechanisms that may affect walking can lead to better targeted prevention and treatment interventions.

Method

Participants

Data were collected as part of a larger, population-based, prospective cohort study of Hispanic older adults in Miami, Florida, titled “The Hispanic Elders' Behavioral Health Study,” which focuses on the relationship between neighborhood environmental factors and older adults' well-being, specifically the built (physical) environment and residents' mental health outcomes (for further details on the larger project, please consult Brown et al., 2009). To obtain a population-based sample, all 16,000 households in a single urban Miami community were enumerated to identify all Hispanic adults 70 years or older. One Hispanic older adult was randomly selected from each block in which at least one older adult lived. Of all 3,322 older adults enumerated, 521 were randomly chosen and approached for participation. To participate, individuals at baseline had to (a) be 70 years of age or older, (b) have immigrated from a Spanish-speaking country, (c) reside in this specific Miami neighborhood, (d) reside in housing in which he or she can walk outside (excluded nursing homes), (e) be of sufficient physical health to go outside, and (f) score 17 or above on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), a test of global cognitive functioning. Of the 521 initially approached, 30 had died since enumeration, 87 had moved or could not be located/contacted, 95 refused participation, 10 had incorrect home addresses, 24 did not meet full eligibility criteria, and 2 moved to a different block from which a participant had already been sampled, resulting in 273 participants who provided informed consent and completed the baseline assessment.

Participants completed yearly, home-based assessments in Spanish. This study utilizes data collected at the 2-year follow-up (the study's third assessment time point) because walking behavior was not assessed at the preceding baseline or 1-year follow-up assessments. The 2-year follow-up was completed between 2004 and 2005, and the sample had decreased from 273 to 217. Attrition was due to death (n = 25), refusal (n = 11), moving out of the region (n = 7), and loss to follow up (n = 13). Compared with participants remaining at follow-up, participants who were lost to follow-up were older (80.48 vs. 77.96; F(1, 269) = 5.1, p = .008) and more likely to be male (63.0% vs.43.9%; χ2 = 6.80, p = .009). There were no statistically significant differences between participants who remained or were lost to follow-up on baseline education, income, marital status, depression score, or social support. Fewer than 1% of yearly evaluations were missed by survivors at each time point for reasons other than those given above (i.e., the participant could not be engaged for that year's evaluation). Additional missing data for the measures of depressive symptoms, social support, and walking were less than 1% (i.e., the participant either refused or could not complete either the depressive symptoms or the physical activity measure).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Depressive Affect subscale of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale or CES-D (Radloff, 1977), which reliably assesses depressive mood symptoms while removing somatic symptoms that are at least partly confounded with age and physical health in older populations (Fonda & Herzog, 2001). This subscale is made up of seven items assessing depressive symptoms in the preceding week, such as “I felt lonely” and “I had crying spells.” Responses are made on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 = rarely or none of the time (<1 day) to 3 = most or almost all of the time (5-7 days). A continuous total sum score is computed such that higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms. The Cronbach's alpha in this sample was .82. The CES-D has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and has been used successfully with Hispanic and Spanish-speaking older adults (Black et al., 1999).

Social support was assessed using four indicators of social support. The first, overall social support, was composed of 10 items measuring frequency/amount of social support received by the participant in the last month (Krause & Markides, 1990). It is scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 = never to 3 = very often. The Cronbach's alpha was .81. This 10-item scale is made up of the following three social support subscales: (a) Instrumental Social Support made up of two items on assistance received with daily tasks such as chores, groceries, and the like (Cronbach's α = .73); (b) Emotional Social Support made up of four items involving supportive behaviors received related to comfort and caring (α = .74); and (c) Informational Social Support made up of four items related to advice and information received (α = .81).

Walking

Participants were asked to report their walking routes during the preceding 7 days using the timeline follow-back technique (Sobell & Sobell, 1996), an established interview method that uses a calendar as a cue to remind the respondent of life events in the last week. The events are recorded on the calendar to assist recall before asking for target behaviors (in this case, walking). In this method, the assessor begins by producing a 7-day calendar form and placing the day of the week for each of the 7 days, asking the participant to recall events that have occurred in any of the past 7 days, including destinations outside the home (e.g., trip to the doctor, friend's birthday). Next, the assessor shows the calendar form to the older adults, along with a large map of the neighborhood. The calendar is used to cue the participant's memory for his or her behaviors in the last 7 days that might be associated with walking (e.g., walking to a friend's house for a birthday). Then, the assessor shows the participant where he or she lives on the map and asks the participant where he or she walked on for each day's walking trip and what route he or she took to get there. The assessor traces the actual route walked on the map and notes the specific blocks walked. This process is repeated for the return route, including a note of any transportation that the older adult might have taken on either the initial or return trips (e.g., car, bus, taxi). Data were transformed into a specific identification number assigned to that block, and the number of blocks that are walked is then summed to obtain “total blocks walked.”

Control variables include gender, age, years of education, marital status (married versus unmarried), perceived financial strain, and body mass index (BMI). Perceived financial strain was assessed using a single item about how difficult it was to pay for basic needs using a response scale ranging from 1 = easy to 7 = very difficult. Participant height (measured in meters) and weight (measured in kilograms) were assessed and used to calculate BMI, an indirect measure of body fat computed as weight (kg) / [height (m)]2 (CDC, 2010).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the University of Miami's Institutional Review Board. Participants who evidenced suicide ideation or clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms were assessed by a study psychologist or mental health counselor and were referred for further mental health assistance in the community.

Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, 2008). Preliminary analyses examined variable distributions and sample characteristics. Statistical analyses investigated whether the relationship between older adults' depressive symptoms and walking varied by the amount of social support they received. In terms of walking, both the likelihood of walking (binary variable of number of blocks walked vs. any blocks walked) and the amount of walking (continuous variable of number of blocks walked) were examined. For the binary outcome, logistic regression analyses examined the interaction of depressive symptoms and social support using the outcome variable of no walking versus walking. For the continuous outcome, a negative binomial regression was used because of the count nature of the outcome variable (e.g., number of blocks walked) as well as the fact that the variable was substantially skewed.

To test the moderation effect of the social support variables, the interactions of depressive symptoms by overall social support, instrumental social support, emotional social support, and informational social support were tested separately for significance in the regression analyses. For both analyses, main effects for depressive symptoms and social support were also entered into the regression. If a significant Depressive symptoms × Social support interaction was found, regression analyses were reconducted separately for the subpopulation using the median split on the social support variable. Analyses controlled for age, gender, education, marital status, perceived financial strain, and BMI.

Results

Sample characteristics and descriptive information

The mean age was 79.95 (SD = 6.0; range = 72-102). Sixty-two percent were female. Baseline statistics indicate that all participants were Hispanic, 86% being Cuban and 10% from Central or South American countries. Participants had lived in the United States for an average of 29 years. The sample was of low SES, with 71% reporting annual household income less than US$10,000 and most reporting working-class jobs prior to retirement (e.g., factory worker, housekeeper). The sample averaged 7.1 years of education (SD = 4.3; range = 0-20 years). Approximately, 32% (n = 69) of participants were married and 75% were not. Of the 145 unmarried, approximately 55% (80) were widowed, 32% (47) were divorced, and 12% (18) were never married.

Ranges, means, and standard deviations for the main study and control variables are presented in Table 1. The average score on depressive symptoms was 3.87 (SD = 4.18; range = 0-18). As noted, the walking behavior variable (i.e., blocks walked) was skewed, with a mean of 25.2 (SD = 40.4; range = 0-302). Approximately, 44% (n = 93) of participants did not walk any blocks at all (i.e., nonwalkers), whereas 56% (n = 120) had walked at least one block (i.e., walkers).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Main and Control Variables.

| Variable | N | Range | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main study variables | ||||

| Depressive symptoms | 212 | 0-18 | 3.87 | 4.18 |

| Social support | ||||

| Total | 212 | 0-26 | 10.09 | 5.88 |

| Instrumental | 211 | 0-6 | 3.24 | 2.45 |

| Emotional | 212 | 0-12 | 5.08 | 2.85 |

| Informational | 212 | 0-8 | 1.76 | 2.12 |

| Blocks walkeda | 213 | 0-302 | 25.20 | 40.40 |

| Control variables (continuous onlyb) | ||||

| Age | 212 | 72-102 | 79.95 | 6.00 |

| Education | 211 | 0-20 | 7.14 | 4.28 |

| Financial need | 212 | 1-7 | 3.33 | 2.00 |

| BMI | 202 | 16.04-52.67 | 27.49 | 5.20 |

Note. BMI = body mass index.

56% (n = 120) walked at least 1 block. 44% (n = 93) did not walk at all.

Categorical control variables of gender and marital status reported in text.

Regression and moderator analyses

As shown in Table 2, the negative binomial regression showed a significant main effect between depressive symptoms and walking such that higher levels of depressive symptoms were related to fewer blocks walked (b = −.083, p = .003). Results also show a significant main effect of social support on walking such that higher levels of instrumental social support were related to fewer blocks walked (b = −.232, p < .001). Control variables in this analysis were gender, age, education, financial strain, marital status, and BMI.

Table 2. Negative Binomial Regression and Logistic Regression Results.

| Logistic regression (Dependent variable: walking vs. no walking) | Negative binomial regression (Dependent variable: number of blocks walked) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Main effects model: b (SE) | Model with interaction: b (SE) | Main effects model: b (SE) | Model with interaction: b (SE) | |

| Depressive symptoms | −.074 (.04); p = .066 | .051 (.07); p = .495 | −.083 (.03); p = .003 | −.022 (.04); p = .557 |

| Instrumental social support | −.211 (.08), p = .005 | −.073 (.10); p = .457 | −.232 (.05); p < .001 | −.148 (.06); p = .014 |

| Interaction of Depressive symptoms × Instrumental social support | — | −.036 (.02); p = .044 | — | −.018 (.01); p = .058 |

Note. Control variables: gender, age, education, financial strain, marital status, and body mass index.

For the models including the interaction terms, the logistic regression analysis showed that controlling for these same variables, instrumental social support significantly moderated the relationship between depressive symptoms and the likelihood of walking (b = −.036; OR = 0.97, p = .044). Similarly, the negative binomial regression showed a marginally significant interaction between depressive symptoms and instrumental social support as related to number of blocks walked (b = −.018, p = .058).

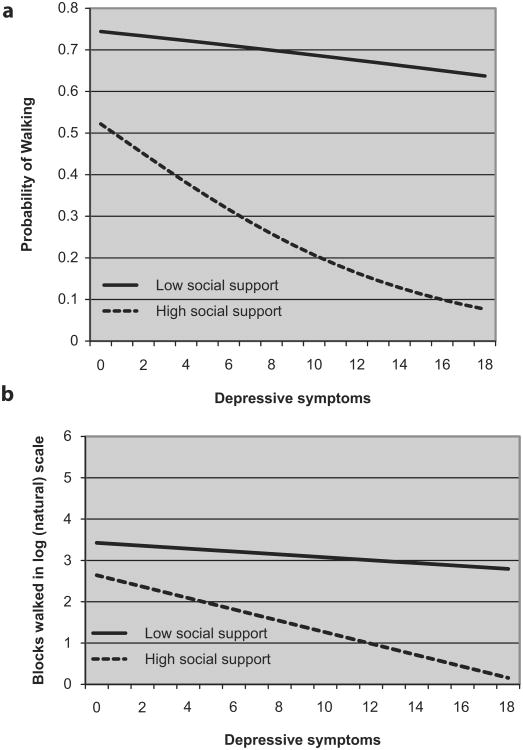

Post hoc analyses were subsequently conducted to identify the locus of this interaction by performing a median split of the instrumental support variable and then examining whether depressive symptoms were associated with the likelihood of walking (versus not walking) separately for those older adults in the lower half of instrumental support scores and those in the upper half of instrumental support scores. These findings are illustrated in Figure 1 (a and b). Again, adjusting for the same control variables, higher depressive symptoms were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of walking but only for participants receiving higher levels of instrumental social support (b = −.143; OR = 0.87, p = .023). Depressive symptoms were unrelated to the likelihood of walking for participants receiving lower levels of instrumental support (b = −.028; OR = 0.97, p = .654). Similarly, higher depressive symptoms were related to less walking (i.e., fewer blocks walked) for those with higher levels of instrumental social support (b = −.138, p < .001). However, depressive symptoms were not related to the amount of walking for those with lower levels of instrumental social support (b = −.035, p = .319). There were no statistically significant interactions between depressive symptoms and any of the other three social support variables in relation to the likelihood of walking or amount of walking, including overall social support, emotional or informational social support.

Figure 1. Relationship between depressive symptoms and (a) probability of walking and (b) amount of walking (i.e., number of blocks walked) by amount of instrumental social support received (high vs. low).

Discussion

Initial study results indicate that higher levels of depressive symptoms were significantly related to fewer blocks walked. This finding supports the conclusions of several previous research studies that depressive symptoms may interfere with older adults' walking behavior (Dunn et al., 2001; Krause et al., 1993; Kritz-Silverstein et al., 2001; Penninx, Leveille, Ferrucci, van Eijk, & Guralnik, 1999; Perrino, Mason, Brown, & Szapocznik, 2010). This is important, given the health benefits associated with physical activity (Bath & Morgan, 1998; Taylor et al., 2004).

The interaction analyses found no evidence that functional social support (i.e., total, emotional, informational, instrumental support) buffered the negative impact of depressive symptoms on walking, as suggested by the stress buffering theory of social support (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Instead, results show evidence that receiving high levels of instrumental social support was related to a lower likelihood of walking among older adults with high levels of depressive symptoms. In contrast, among older adults receiving lower levels of instrumental support, there was no significant relationship between depressive symptoms and the likelihood of walking.

Although some forms of social support have been found to promote health and health behaviors (Dean et al., 1990; Uchino et al., 1996), the present findings suggest that too much instrumental support, for example, assistance with chores and shopping, may have the reverse effect by reducing the likelihood of walking among depressed older adults. Even well-intentioned efforts by family members or caregivers to help older adults by completing daily tasks for them may inadvertently eliminate their need or motivation to walk. These supportive acts can limit opportunities to obtain some of the salutary effects associated with walking.

An alternate way by which instrumental support may lower older adults' likelihood of walking is by interfering with their self-efficacy to walk. When daily living tasks are carried out for them, older adults may receive the implicit message that they are unable or ineffective at doing the tasks themselves, thus reducing their self-efficacy for walking (Clark, 1999; Lee, Arthur, & Avis, 2008) and conceivably encouraging helplessness and dependence (see, for example, Langer & Rodin, 1976; Lawton, Moss, Winter, & Hoffman, 2002). Indeed, self-efficacy in one's own exercise ability is an important predictor of physical activity among older adults (Booth et al., 2000). Similarly, providing too much instrumental support may reduce opportunities to independently engage in activities that may enhance feelings of accomplishment and self-worth. For instance, Lawton et al. (2002) found that engaging in “personal projects,” which may include personal care, shopping, and home maintenance, was related to positive mental health and feelings of accomplishment in older adults. Similarly, personal responsibility for tasks has been found to enhance older adults' alertness, active participation, and feelings of well-being (Langer & Rodin, 1976), and engagement in these activities can provide critical opportunities for personal reinforcement, ultimately improving mental health (see Fiske, Wetherell, & Gatz, 2009).

Indeed, it is likely that a good person–environment fit between the individual's competencies and the support provided by the environment is an important determinant of walking behavior among older adults. In Lawton and Nahemow's Competence-Press Model (1973), an individual's level of adaptive behavior is a consequence of environmental demands that are commensurate with his or her competencies. Consistent with this model, an environment in which daily living tasks are performed for an able older adult may encourage sedentary behavior.

Other research findings support the present study's results. In a cross-sectional study of veterans with cancer, Sultan et al. (2004) found that more instrumental support was related to poorer physical health–related quality of life. It is possible that receiving too much instrumental support may have interfered with potentially beneficial health behaviors such as physical activity, which may ultimately impact perceived physical health (Nelson et al., 2007). Others have found that high levels of instrumental social support increase the risk of disability among older adults (Hays, Saunders, Flint, Kaplan, & Blazer, 1997; Mendes de Leon, Gold, Glass, Kaplan, & George, 2001; Seeman, Bruce, & McAvay, 1996). The process of “deconditioning” is hypothesized to be the operating force, whereby receiving assistance diminishes the older adult's ability to carry out these tasks and function independently (Siegler, Stineman, & Maislin, 1994). Similarly, physical activity is related to better physical functioning and lower risk of disability among older adults (see Nelson et al., 2007). It has been argued that social support will promote health only if it encourages personal competence and self-efficacy to engage in health-protective behaviors (Berkman, 1995).

Another notable finding from the current study is that other forms of social support, including emotional, informational, and total levels of social support, did not affect the relationship between depressive symptoms and walking, either positively or negatively. Unlike instrumental support, neither emotional nor informational support involves physically performing tasks for the older adult, and this may be the reason why these forms of support did not affect walking behavior. Moreover, it is important to consider that the receipt of support does not necessarily mean that is it positive, welcome, or helpful in ameliorating depressive symptoms or the consequences of depressive symptoms. For instance, Cruza-Guet, Spokane, Caskie, Brown, and Szapocznik (2008) found that informational support (e.g., advice, explanations) was associated with greater psychological distress among the older adults in the current study's sample. The authors hypothesize that older adults may dislike receiving advice or explanations, interpreting this type of information as critical or implying cognitive decline, further increasing the older adult's distress levels. Nagumey, Reich, and Newsom (2004) found that older men who reported a preference for being more independent were more likely to have negative responses to receiving social support. Tucker (2002) found that attempts by social network members to influence older adults' health behaviors can result in positive health behaviors; however, when there is limited satisfaction with these relationships, older adults may show negative affect as well as attempt to hide unhealthy behaviors. Indeed, certain social interactions or patterns can have a negative impact on physical and mental health (see Seeman, 2000).

This study has a number of limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not permit a determination regarding the causal direction of these relationships or whether bidirectional relationships between the variables may be present. This limits the conclusions that can be drawn from these analyses. Second, the sample size is fairly small and the low levels of walking in this group may have resulted in insufficient power to detect significant interaction effects with some of the social support variables or more than a marginally significant interaction effect for the continuous outcome variable of amount of walking. Third, analyses did not directly control for health and disability even though these factors can be related to depressive symptoms, physical inactivity (Berkman et al., 1986; Lian, Gan, Pin, Wee, & Ye, 1999), and amount of social support received. However, the use of the CES-D measure's Depressive Affect subscale may provide some control for the effects of health and disability. As noted, this subscale reliably assesses depressive mood symptoms without the somatic symptoms items, which are at least partly confounded with age and physical health in older populations (Fonda & Herzog, 2001). Fourth, although the study's physical activity measure assesses walking, the most common form of physical activity among older adults (CDC, 1999), the self-report measure has certain shortcomings. It is not an objective measure, such as pedometers or accelerometers, it only assesses walking in the preceding week, and it does not assess the intensity, duration, or regularity of walking, all of which can impact health outcomes (Nelson et al., 2007).

There are characteristics of the present study's sample that may have further influenced the findings. This sample is composed of an “older” sample of older adults (70 to 100 years old), who may be at greater risk of health problems and less likely to engage in physical activity than “younger” older adults (Kaplan et al., 1991; Newsom, Kaplan, Huguet, & McFarland, 2004). Nonetheless, low rates of physical activity are common among older adults across the United States (Eyler, Brownson, Bacak, & Housemann, 2003; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 1996), particularly Hispanics and other minority groups (Kruger, Ham, & Sanker, 2008, Marquez et al., 2004), including those of low SES (Yancey et al., 2005). As such, the study's findings are most likely to reflect the reality of many present-day, disadvantaged older adults.

This study's findings add to the literature by establishing a connection between depressive symptoms, social support, and walking, and offering an additional explanation of how depressive symptoms might influence walking behavior among older adults. It is important to stress that these results do not suggest that family members and caregivers should limit or withhold social support from older adults. Instead, they suggest that as depressive symptoms increase, social support must be well targeted to the older adults' true needs. That is, instrumental assistance should be commensurate with, but not substantially exceed, the person's real physical need for assistance (e.g., Langer & Rodin, 1976; Lawton, 1985). Otherwise, there is a risk that this assistance might interfere with physical activity, reducing opportunities for older adults to experience the salutary benefits that walking and completing these tasks can provide. Indeed, the findings suggest that providing emotional and informational social support does not carry a risk of interfering with older adults' walking behavior. Although examining and replicating these findings in other samples and in longitudinal studies will be necessary, clinicians serving older adults with depressive symptoms may be well served to monitor the type and amount of support provided by others to ensure there are no unintended consequences on health behaviors. Given the challenges of successfully preventing and managing depression and physical inactivity among older adults (see Fiske et al., 2002; King et al., 1998), a better understanding of the mechanisms by which depressive symptoms and physical inactivity are related should lead to more targeted prevention interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This work was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant No. MH 63709 (J. Szapocznik, PI; A. Spokane, co-PI), by a National Institute on Aging Grant No. AG 027527 (J. Szapocznik, PI; S. Brown, co-PI), by a National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases Grant No. DK 74687 (J. Szapocznik, PI), and by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Grant No. 037377.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The online version of this article can be found at: http://jah.sagepub.com/content/23/6/974

References

- Barnett PA, Gotlib IH. Psychosocial functioning and depression: Distinguishing antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;104(1):97–126. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.104.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Epidemiological evidence for the role of physical activity in reducing risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99:1193–1204. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00160.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath PA, Morgan K. Customary physical activity and physical health outcomes in later life. Age & Ageing. 1998;27(S3):29–34. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.suppl_3.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1995;57:245–254. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Berkman CS, Kasl S, Freeman DH, Leo L, Ostfeld AM, et al. Brody JA. Depressive symptoms in relation to physical health and functioning in the elderly. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;124:372–388. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Espino DV, Mahurin R, Lichtenstein MJ, Hazuda HP, Fabrizio D, … Markides KS. The influence of noncognitive factors on the mini-mental state examination in older Mexican Americans: Findings from the Hispanic EPESE—Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52:1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Markides KS, Miller TQ. Correlates of depressive symptomatology among older community-dwelling Mexican Americans: The Hispanic EPESE. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1998;53B:S198–208. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth ML, Owen N, Bauman A, Clavisi O, Leslie E. Social-cognitive and perceived environmental influences associated with physical activity in older Australians. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:15–22. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SC, Mason CA, Lombard JL, Martinez F, Plater-Zyberk E, Spokane AR, et al. Szapocznik J. The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of “eyes on the street”. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2009;64B:234–246. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity and health: Older adults. 1999 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/sgr/olderad.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About BMI for adults. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html.

- Clark DO. Physical activity and its correlates among urban primary care patients aged 55 years and older. Journals of Gerontology Psychological & Social Sciences. 1999;54(1):S41–48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.1.s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PB. Fatigue and physical activity in older women after myocardial infarction. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care. 2005;34(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo CJ, Ainsworth BE, Keteyian SJ, Heath GW, Smit E. Prevalence of physical inactivity and its relation to social class in U.S. adults: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1999;31:1821–1827. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199912000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruza-Guet MC, Spokane AR, Caskie GIL, Brown SC, Szapocznik J. The relationship between social support and psychological distress among Hispanic elders in Miami, Florida. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:427–441. doi: 10.1037/a0013501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean A, Kolody B, Wood P. Effects of social support from various sources on depression in elderly persons. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1990;31:148–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O'Neal HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2001;33:S587–S597. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler AA, Brownson RC, Bacak SJ, Housemann RA. The epidemiology of walking for physical activity in the United States. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2003;35:1529–1536. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084622.39122.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcón LM, Tucker KL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among Hispanic elders in Massachusetts. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;55B(2):S108–S116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Aggarwal BA, Liao M, Mosca L. Physical activity as a potential mechanism through which social support may reduce cardiovascular risk. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2008;23(2):90–96. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305074.43775.d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:363–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonda SJ, Herzog R. Patterns and risk factors of change in somatic and mood symptoms among older adults. Annals of Epidemiology. 2001;11:361–368. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Health Psychology. 2009;28:354–363. doi: 10.1037/a0014400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays JC, Saunders WB, Flint EP, Kaplan BH, Blazer DG. Social support and depression as risk factors for loss of physical function in late life. Aging & Mental Health. 1997;1:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvensalo M, Rantanen T, Heikkinen E. Mobility difficulties and physical activity as predictors of mortality and loss of independence in the community-living older population. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2000;48:493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsten M, Mittleman MA, Wamala SP, Schenck-Gustaffson K, Orth-Gomer K. Social relations and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged Swedish women. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk. 1999;6:391–397. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan GA, Lazarus NB, Cohen RD, Leu DJ. Psychosocial factors in the natural history of physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1991;7:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78:458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Rejeski WJ, Buchner DM. Physical activity interventions targeting older adults: A critical review and recommendations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;15:316–333. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Goldenhar L, Liang J, Jay G, Maeda D. Stress and exercise among the Japanese elderly. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;36:1429–1441. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90385-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Markides K. Measuring social support among older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1990;30(1):37–53. doi: 10.2190/CY26-XCKW-WY1V-VGK3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Rook KS. Negative interactions in late life: Issues in the stability and generalizablity of conflict across relationships. Journal of Gerontology Psychological & Social Sciences. 2003;58:P88–99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E, Corbeau C. Cross-sectional and prospective study of exercise and depressed mood in the elderly. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;153:596–602. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J, Ham SA, Sanker S. Physical inactivity during leisure time among older adults—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2005. Journal of Aging & Physical Activity. 2008;16:280–291. doi: 10.1123/japa.16.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer EJ, Rodin J. The effects of choice and enhanced personal responsibility for the aged: A field experiment in an institutional setting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1976;34:191–198. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.34.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. The elderly in context: Perspectives from environmental psychology and gerontology. Environment and Behavior. 1985;17:501–519. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Moss MS, Winter L, Hoffman C. Motivation in later life: Personal projects and well-being. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:539–547. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Nahemow LE. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer&M C, Lawton MP, editors. The psychology of adult development and aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1973. pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Lee LL, Arthur A, Avis M. Using self-efficacy theory to develop interventions that help older people overcome psychological barriers to physical activity: A discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45:1690–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian WM, Gan GL, Pin CH, Wee S, Ye HC. Correlates of leisure-time physical activity in an elderly population in Singapore. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1578–1580. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L. Personal or environmental causes of happiness: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;139(1):79–90. doi: 10.1080/00224549909598363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado GPM, Gignac MAM, Badley EM. Participation restrictions among older adults with osteoarthritis: A mediated model of physical symptoms, activity limitations, and depression. Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Care & Research) 2008;59(1):129–135. doi: 10.1002/art.23259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez DX, McAuley E, Overman N. Psychosocial correlates and outcomes of physical activity among Latinos: A review. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science. 2004;26:195–229. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon CF, Gold DT, Glass TA, Kaplan L, George LK. Disability as a function of social networks and support in elderly African Americans and Whites: The Duke EPESE 1986-1992. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56B:S179–190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.3.s179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon CF, Rapp SS, Kasl SV. Financial strain and symptoms of depression in a community sample of elderly men and women: A longitudinal study. Journal of Aging and Health. 1994;6:448–468. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan K, Bath PA. Customary physical activity and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Age & Ageing. 1998;27:35–40. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.suppl_3.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagumey AJ, Reich JW, Newsom JT. Gender moderates the effects of independence and dependence desires during the social support process. Psychology & Aging. 2004;19:215–218. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, et al. Castaneda-Sceppa C. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1094–1105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Kaplan MS, Huguet N, McFarland BH. Health behaviors in a representative sample of older Canadians: Prevalences, reported change, motivation to change, and perceived barriers. Gerontologist. 2004;44:193–205. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Schulz R. Caregiving from the recipient's perspective: Negative reactions to being helped. Health Psychology. 1998;17:172–181. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HQ, Koepsell T, Unutzer J, Larson E, LoGerfo JP. Depression and use of a health plan sponsored physical activity program by older adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(2):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka RK, King AC, Young DR. Sources of social support as predictors of exercise adherence in women and men ages 50 to 65 years. Women & Health. 1995;1:161–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JTM, Guralnik JM. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: Longitudinal evidence from the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Brown SC, Mason CA, Szapocznik J. Depressive symptoms among urban Hispanic older adults in Miami: Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates. Clinical Gerontologist. 2009;32:26–42. doi: 10.1080/07317110802478024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Mason CA, Brown SC, Szapocznik J. The relationship between depressive symptoms and walking among Hispanic older adults: A longitudinal, cross-lagged panel analysis. Aging & Mental Health. 2010;14:211–219. doi: 10.1080/13607860903191374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SL, Haley WE, Kozlenko N. The impact of depressive symptoms and chronic diseases on active life expectancy in older Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16:425–432. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816ff32e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satariano WA, Haight TJ, Tager IB. Reasons given by older people for limitation or avoidance of leisure time physical activity. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:505–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE. Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2000;14:362–370. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Bruce ML, McAvay GJ. Social network characteristics and onset of ADL disability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1996;54B:S214–222. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.4.s191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shores KA, West ST, Theriault DS, Davison E. Extra-individual correlates of physical activity attainment in rural older adults. Journal of Rural Health. 2009;25:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler EL, Stineman MG, Maislin G. Development of complications during rehabilitation. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1994;154:2185–2190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Ruiz JM. Psychosocial influences on the development and course of coronary heart disease: Current status and implications for research and practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:548–568. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback user's guide: A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug abuse. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS, Inc. SPSS for Windows 18. Chicago, IL: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl T, Rutten A, Nutbeam D, Kannas L, Abel T, Luschen G, et al. van der Zee VJ. The importance of the social environment for physically active lifestyle— Results from an international study. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan S, Fisher DA, Voils CI, Kinney AY, Sandler RS, Provenzale D. Impact of functional social support on health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:2737–2743. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AH, Cable NT, Faulkner G, Hillsdon M, Narici M, Van der Bij AK. Physical activity and older adults: A review of health benefits and effectiveness of interventions. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2004;22:703–725. doi: 10.1080/02640410410001712421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS. Health-related social control within older adults' relationships. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:P387–95. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.p387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. What a lifespan approach might tell us about why distinct measures of social support have differential links to physical health. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2009;26(1):53–62. doi: 10.1177/0265407509105521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Keicolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1987;28:306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity and health: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Author; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey AK, Robinson RG, Ross RK, Washington R, Goodell HR, Goodwin NJ, et al. Wong MJ. Discovering the full spectrum of cardiovascular disease: Minority Health Summit 2003—American Heart Association Advocacy Writing Group. Circulation. 2005;111(10):e140–149. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157744.30181.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]