Abstract

Objective

To understand rates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability and factors correlated with HPV vaccine acceptability.

Design

Meta-analyses of cross-sectional studies.

Data sources

We used a comprehensive search strategy across multiple electronic databases with no date or language restrictions to locate studies that examined rates and/or correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability. Search keywords included vaccine, acceptability and all terms for HPV.

Review methods

We calculated mean HPV vaccine acceptability across studies. We conducted meta-analysis using a random effects model on studies reporting correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability. All studies were assessed for risk of bias.

Results

Of 301 identified studies, 29 were included. Across 22 studies (n=8360), weighted mean HPV vaccine acceptability=50.4 (SD 21.5) (100-point scale). Among 16 studies (n=5048) included in meta-analyses, perceived HPV vaccine benefits, anticipatory regret, partner thinks one should get vaccine and healthcare provider recommendation had medium effect sizes, and the following factors had small effect sizes on HPV vaccine acceptability: perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness, need for multiple shots, fear of needles, fear of side effects, supportive/accepting social environment, perceived risk/susceptibility to HPV, perceived HPV severity, number of lifetime sexual partners, having a current sex partner, non-receipt of hepatitis B vaccine, smoking cigarettes, history of sexually transmitted infection, HPV awareness, HPV knowledge, cost, logistical barriers, being employed and non-white ethnicity.

Conclusions

Public health campaigns that promote positive HPV vaccine attitudes and awareness about HPV risk in men, and interventions to promote healthcare provider recommendation of HPV vaccination for boys and mitigate obstacles due to cost and logistical barriers may support HPV vaccine acceptability for men. Future investigations employing rigorous designs, including intervention studies, are needed to support effective HPV vaccine promotion among men.

Keywords: Hpv, Vaccination, Men, Meta-Analysis, Attitudes

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI), causing a substantial burden of disease in men and women.1 2 In the USA, half of sexually active men and women contract HPV at some point in their lives.1 The prevalence of anal HPV infection is estimated at around 15% in heterosexual men, 60% in men who have sex with men (MSM) who are HIV negative, and 95% in HIV positive MSM.3–5

Worldwide, the majority of anal and penile cancers among men are associated with HPV infection.6 7 The high prevalence of anal HPV among MSM is associated with 44 times higher incidence of anal cancer,7 and among HIV positive MSM approximately 60 times higher incidence of anal cancer than that of the general population.8 Heterosexual men infected with HPV, in addition to increasing their own risks of anal and penile cancers, may contribute to increasing female sexual partners’ risks of developing cervical cancer.9

HPV vaccination for men

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (HPV4; Gardasil) was licensed in the USA for men in 2009.10 In 2011 the US Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices approved and recommended routine use of HPV4 for boys aged 11–21 years, with approval for administration up to age 26 years, in order to prevent genital warts and anal cancer.10 HPV4 is recommended for MSM through age 26 years. HPV4 is over 90% effective in preventing a variety of types of HPV infection and genital warts in young men.11 It has also demonstrated efficacy among MSM in preventing anal epithelial neoplasias that are precursors to anal cancer.12

Nevertheless, substantial debate surrounds HPV4 vaccination programmes for men.13 Based on mathematical models suggesting that male HPV4 vaccination programmes exceed cost-effectiveness thresholds,14–16 many European countries do not include men in HPV vaccination programmes, as in the USA, Canada and Australia,10 17 18 instead focusing on achieving expanded coverage among women to promote herd immunity.19 Support for male HPV4 vaccination programmes is based on evidence of substantial clinical benefits to men,20 cost-effectiveness among MSM,21 largely excluded from mathematical models, increased cost-effectiveness for men with the addition of non-cervical outcomes to mathematical models,15 22 23 and benefits of a gender-neutral (universal) approach to vaccination.17 22 24 Furthermore, most mathematical models calling into question the cost-effectiveness of male HPV4 vaccination presume 70% or greater coverage among women,14–16 an estimate that is not supported by data from the USA (three-dose coverage in women ∼32%)10 and many European countries.19

HPV vaccine acceptability

Vaccine acceptability is a crucial factor in uptake.23 The majority of investigations of HPV vaccine acceptability have focused on women.25 A systematic review of six US studies focused on young women identified HPV vaccine acceptability ranging from 55% to 100% although meta-analysis was not conducted and results were not disaggregated by sex.26

A review of 23 quantitative and qualitative studies of HPV vaccine acceptability for men reported a range of acceptability from 33% to 78%.25 The majority of studies indicated parents and healthcare providers (HCP) were more supportive of HPV vaccination for women than men.25 Two review articles,22 23 one after US licensure of HPV4 for men,22 describe challenges to achieving broad coverage and the importance of understanding vaccine acceptability for men.

In light of current US recommendations for HPV vaccination of men,10 we conducted quantitative syntheses (meta-analyses, weighted mean acceptability, t tests) to assess: (1) rates of HPV vaccine acceptability and (2) factors correlated with HPV vaccine acceptability among men.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We followed preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.27 We included original research studies using quantitative methods that examined rates of HPV vaccine acceptability and/or barriers, facilitators, attitudes, sociodemographic characteristics or other factors associated with acceptability of HPV vaccines. Studies that did not use quantitative methods, report original data, include men or examine HPV vaccine acceptability were not included in this analysis. Types of participants included men reporting on HPV vaccine acceptability. We contacted corresponding authors to provide missing and unreported data or raw data sets when studies did not report sufficient information to be included in meta-analyses.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was HPV vaccine acceptability rates among men. The secondary outcomes were factors associated with HPV vaccine acceptability: sociodemographic characteristics, HPV vaccine attitudes, HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge, HPV risk perceptions, behavioural risk, HPV vaccine endorsements and structural factors.

Search strategy

We used a comprehensive search strategy to locate articles meeting inclusion criteria across multiple electronic databases: Cochrane Library, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, AIDSLine, CINAHIL, EMBASE, PsychInfo, Social Science Abstracts, Ovid MEDLINE, Scholars Portal, Social Sciences Citation Index, Dissertation Abstract International, ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts database, Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSA) Sociological Abstracts, Proquest Research Library, CSA Social Services Abstracts database and AgeLine Database. Databases were searched with no language, geographical or time restrictions; the last search date was 1 March 2013.

Data collection process

All titles and abstracts from the reference lists of articles were screened for inclusion. The full article was obtained when the first reviewer determined the article might meet inclusion criteria based on the study objectives. Two reviewers (CHL and KA or ND) then assessed each article for inclusion based on study type and outcome measures, with a third reviewer (PAN) available to arbitrate in case of disagreement.

Data extraction

We developed a data extraction form using Microsoft Excel. Two reviewers (CHL, KA or ND) extracted the following data: article information (ie, year of publication, author, journal); descriptive data (ie, sample size, country, participant demographics); methods and study design; and outcomes/key findings. Data regarding any variables examined as possible correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability was sought. We developed a list of themes related to HPV vaccine acceptability based on review of the variables explored in the included articles.

Risk of bias

We assessed risk of bias using items from the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) ‘Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies’,28 which we modified for use with cross-sectional studies. We assessed selection bias (representativeness of sample, participation rate), data collection method (validity, reliability) and study design using a rating rubric to determine if each component had low, moderate or high risk of bias.28 Studies with no ‘high risk of bias’ ratings were considered to have an overall low risk of bias, one ‘high risk of bias’ rating moderate risk of bias, and more than one ‘high risk of bias’ rating a high overall risk of bias. No studies were excluded on the basis of risk of bias.

Data analysis

For studies that quantified HPV vaccine acceptability, we linearly transformed acceptability ratings onto a 0–100 scale. We calculated mean HPV vaccine acceptability for each study and weighted mean acceptability overall. Subgroup analyses were prespecified. For studies that reported participant sexual orientation we calculated weighted mean acceptability for gay/bisexual/MSM and heterosexual men, and used unpaired t tests to compare HPV vaccine acceptability by sexual orientation.

Meta-analysis was conducted on studies that examined similar correlates or predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability. We used V.2 of Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software to calculate effect sizes for each variable, with a random effects model to compensate for clinical and methodological diversity between studies. We combined coefficients across studies for each variable that was examined in order to derive a global estimate of its correlation with HPV vaccine acceptability. We calculated the Q statistic to assess homogeneity of correlations across studies (within-study variability) and the I2 index to assess the degree of heterogeneity (between-study variability).

We included all studies examining correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability that provided sufficient data (eg, correlations, ORs, χ2 statistics or t values) in the meta-analysis. As the majority of studies did not evaluate interventions, we did not conduct meta-analysis on dichotomous (intervention vs control group) data.

Results

Study selection

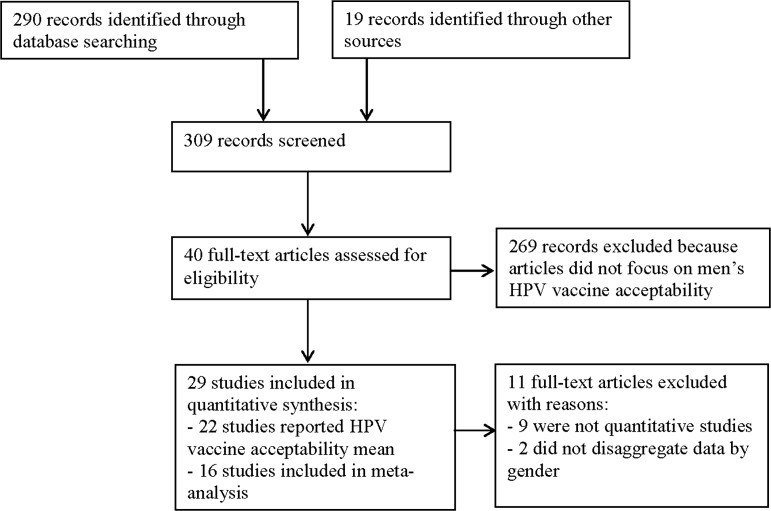

The literature search yielded 309 studies (see figure 1), with 100% agreement between reviewers (CHL, KA or ND) in selecting relevant articles. Of the 40 relevant studies, we excluded 9 because they were not quantitative and 2 because data were not disaggregated by gender. Twenty-nine remaining studies were included in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of articles selection progress for human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among men review.

Study characteristics

Two reviewers (CHL, KA or ND) determined whether the same sample and study were used more than once. The 29 articles9 24 29–55 reflect 24 original studies,9 29 30 34–47 49–55 all published in English. Half (n=12) of the studies were conducted in the USA, three in Australia, two in Sweden (n=2), and one each in Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore and South Korea. Ninety-one per cent (n=21) of the study samples were adult men; two studies were conducted among adolescent boys aged 14–19 years.29 43 Study characteristics and mean HPV vaccine acceptability are outlined in table 1.

Table 1.

Studies addressing human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability, study characteristics and risk of bias, ordered by mean vaccine acceptability (n=29)*

| HPV vaccine acceptability mean† | Author(s) | Population | Age (range, mean) | Sexual orientation/behaviour‡ (%) | Sample size | Country | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 94.0 | Rand et al29 | Adolescents | 15–17, M=N/R | N/R | 22 | USA | High |

| 93.6§ | Daley et al30; Daley et al31 | Adults | 18–70, M=27.8 | N/R | 296 | USA | High |

| 77.5 | Jones et al45 | College students | 18–32, M=N/R | N/R | 138 | USA | High |

| 74.3 | Gottvall et al43 | Adolescents | 14–19, M=16.0 | N/R | 608 | Sweden | High |

| 74.0 | Gilbert et al32; Gilbert et al33; McRee et al48; Reiter et al51 | Adults | 18–59, M=N/R | Gay/bisexual | 306 | USA | Moderate |

| 71.5¶ | Hernandez et al44 | Adults | 18–79, M=N/R | MSM (20.0%); heterosexual (80.0%) | 445 | USA | High |

| 70.8 | Petrovic et al35 | Adults | 18–26, M=22.3 | N/R | 121 | Australia | High |

| 68.8 | Bynum et al38 | College students | N/R, M=20.6 | Heterosexual (91.1%); Gay/bisexual/unsure (4.5%); Unknown (4.5%) | 575 | USA | High |

| 65.8 | Chelimo et al39 | College students | N/R, M=19.8 | N/R | 38 | New Zealand | High |

| 65.5 | Gerend et al42 | College students | 18–24, M=18.8 | Heterosexual | 356 | USA | Low |

| 64.4 | Thomas et al55 | Adults | 22–56, M=36.6 | MSM | 191 | USA | High |

| 62.0 | Daley et al30; Daley et al31 | College students | 18–22, M=N/R | N/R | 198 | USA | High |

| 55.4 | Oh et al49 | Adults | N/R, M=53.1** | N/R | 496 | South Korea | High |

| 48.0 | Lenselink et al46 | College students | 18–25, M=19.8 | N/R | 223 | Netherlands | High |

| 47.3 | Marshall et al47 | Adults | N/R, M=N/R | N/R | 852 | Australia | High |

| 47.0 | Simatherai et al53 | Adults | 19–71, M=27.0** | MSM (100.0%) | 200 | Australia | High |

| 45.3 | Crosby et al40 | College students | 18–24, M=20.2 | History of same-sex experience (6.1%); No same-sex experience (93.9%) | 148 | USA | High |

| 37.0 | Reiter et al9; Gilbert et al32; Gilbert et al33; McRee et al48 | Heterosexual men | 18–59, M=N/R | Heterosexual | 297 | USA | Moderate |

| 36.0 | Wheldon et al34 | Adults | 18–29, M=21.6 | Gay/bisexual | 179 | USA | High |

| 34.3†† | Sundstrom et al54 | Adults | 18–30, M=23** | MSM, heterosexual | 1712 | Sweden | High |

| 33.0 | Ferris et al24; Ferris et al41 | Adults | 18–45, M=N/R | Heterosexual (95.4%), Gay/bisexual (4.6%) | 571 | USA | High |

| 28.9†† | Young et al36 | Adults | 18–31, M=21.2 | N/R | 143 | Philippines | High |

| 8.2 | Blodt et al37 | Vocational students | 18–25, M=N/R | N/R | 245 | Germany | High |

| N/R | Pitts et al50 | Adults | 18–54, M=34.8 | N/R | 930 | Singapore | High |

| N/R | Sauvageau et al52 | Adults | 18–69, M=44.8 | N/R | 154 | Canada | High |

Mean acceptability 56.64 (SD 21.32; median=62.0; SEM 4.45; 95% CI 47.42 to 65.86); N=8360 (22 studies); Range: 8.2–94.0.

Weighted mean acceptability: 50.43 (SD 21.49).

*Twenty-three unique samples were included in calculation of overall mean acceptability.

†Acceptability on a 0–100 point scale.

‡Mean acceptability across race/ethnicity.

§Sexual orientation or behaviour, as reported by authors.

¶Mean acceptability across sexual orientation.

**Median.

††Mean acceptability for vaccines with different costs.

MSM, men who have sex with men; N/R, Not reported.

The majority of studies (n=20; 83%) had high risk of bias,29 34–41 43–47 49 50 52–55 three (13%) moderate risk of bias9 30 51 and one (2%) low risk of bias.42 All studies were cross-sectional in design except for two cohort studies.42 44 Eight studies (33%) used random sampling9 30 37 47 49–52 54; 16 studies used non-random sampling techniques.

Twenty-nine studies quantified HPV vaccine acceptability among men (see table 1). We included 22 studies (n=8360)9 24 29 30 34–47 49 51 53–55 in the calculation of mean HPV vaccine acceptability because in several cases9 24 30–33 41 48 51 different studies were based on the same sample. In one study we treated two samples separately as the authors reported separate means and correlates for men enrolled in a clinical study and college students.30 31 Among these 22 investigations, mean HPV vaccine acceptability ranged from 8.2 to 94.0 with overall mean acceptability of 56.6 (SD 21.3) (weighted mean=50.4, SD 21.5).

In the nine studies that reported HPV vaccine acceptability and sexual orientation, weighted mean acceptability was 58.44 (SD 16.76) among gay/bisexual/MSM (n=986) and 50.98 (SD 19.67) among heterosexuals (n=1713),9 35 41 42 44 51 53–55 although not statistically significant (t (2699)=0.24, p=0.81).

Meta-analytic results: correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability among men

Sufficient data were provided to examine the association between HPV vaccine acceptability and factors in seven categories: sociodemographics, HPV knowledge, HPV risk perceptions, HPV vaccine attitudes, endorsement from others, behavioural risk indicators and structural barriers. Table 2 reports weighted mean correlational effect sizes measuring the association of each factor with HPV vaccine acceptability and 95% CIs, as well as the Q test of homogeneity and I2 index of between-study variability. I2 values of 25% represent low, 50% medium and 75% high heterogeneity.56 Sixteen studies (n=5048) were included in the meta-analysis.9 24 30 34–37 40 42 44–56

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of correlates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability among men (n=16)9 24 30 34–37 40 42 44–56

| Theme | Factor | Number of studies | Effect size | Homogeneity index, Q | Between-study variability, I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV vaccine attitudes | Perceived HPV vaccine benefits | 335 42 52 | 0.51 (0.31, 0.66), p<0.001 | 6.03, p<0.05 | 83.42 |

| Anticipatory regret if not vaccinated | 29 51 | 0.27 (0.21, 0.32), p<0.001 | 0.59, p=0.44 | 0.00 | |

| Perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness | 69 31 37 42 44 51 | 0.19 (0.12, 0.26), p<0.001 | 12.01, p<0.05 | 58.36 | |

| Fear of needles | 430 31 36 40 | −0.11 (−0.21, −0.00), p<0.05 | 2.38, p=0.49 | 0.00 | |

| Fear of side effects | 724 30 35–37 40 44 | −0.09 (−0.14, −0.04), p<0.01 | 3.95, p=0.56 | 0.00 | |

| HPV vaccine endorsements | HCP recommended HPV vaccine | 59 24 30 31 51 | 0.42 (0.13, 0.64), p<0.01 | 50.84, p<0.01 | 92.13 |

| Partner thinks should get vaccine | 224 44 | −0.41 (−0.51, −0.31), p<0.001 | 1.62, p=0.20 | 38.32 | |

| Supportive/accepting social environment | 430 35 36 44 | 0.18 (0.08, 0.27), p<0.001 | 4.82, p=0.19 | 37.65 | |

| HPV risk perceptions | Perceived HPV risk/susceptibility | 109 31 35–37 40 42 45 49 51 | 0.25 (0.15, 0.34), p<0.001 | 40.99, p<0.01 | 78.05 |

| Perceived HPV severity | 79 30 35 40 42 49 51 | 0.09 (0.03, 0.16), p<0.001 | 11.05, p=0.09 | 45.73 | |

| Behavioural risk indicators | Number of lifetime sexual partners | 637 42 44–46 52 | 0.18 (0.09, 0.28), p<0.01 | 11.95, p<0.05 | 58.16 |

| Have a current/recent sex partner | 624 35 36 40 42 46 | 0.17 (0.04, 0.30), p<0.05 | 25.72, p<0.01 | 80.56 | |

| Did not receive hepatitis B vaccine | 29 51 | −0.16 (−0.02, −0.08), p<0.001 | 1.02, p=0.31 | 2.84 | |

| Smokes cigarettes | 49 24 44 51 | 0.12 (0.02, 0.22), p<0.05 | 7.06, p=0.07 | 57.50 | |

| History of STI | 430 40 44 51 | 0.10 (0.01, 0.18), p<0.05 | 2.99, p=0.39 | 0.00 | |

| HPV education | HPV awareness | 424 42 46 51 | 0.17 (0.05, 0.30), p<0.01 | 8.83, p<0.05 | 66.02 |

| HPV knowledge | 109 30 31 34 35 42 45 46 50 51 | 0.09 (0.01, 0.16), p<0.05 | 37.84, p<0.01 | 76.22 | |

| Structural barriers | Cost | 730 31 35 36 40–42 | −0.17 (−0.25, −0.07), p<0.001 | 31.94, p<0.01 | 81.22 |

| Logistical barriers (hassle, time) | 69 30 36 42 44 51 | −0.16 (−0.32, −0.00), p<0.05 | 49.20, p<0.01 | 89.84 | |

| Need for multiple shots | 230 31 | −0.16 (−0.27, −0.05), p<0.01 | 0.23, p=0.89 | 0.00 | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Employed | 39 36 51 | 0.13 (0.03, 0.22), p<0.05 | 0.49, p=0.78 | 0.00 |

| Non-white ethnicity | 89 30 31 35 42 44 45 51 | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15), p<0.01 | 6.86, p=0.44 | 0.00 | |

| Education | 99 30 31 35–37 44 49 51 | 0.08 (−0.00, 0.16), p=0.054 | 15.95, p<0.05 | 49.86 |

HCP, healthcare providers; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

We used a random effects model in the meta-analysis to account for between-study variability. As the small number of studies examining many factors precluded subanalyses of moderator variables or meta-regression, we examined individual results to identify potential reasons for between-study variability. Substantive (ie, participant characteristics) and methodological (ie, sample size) differences may have impacted between-study variability.

We identified factors associated with HPV vaccine acceptability across seven domains.

HPV vaccine attitudes: acceptability was positively correlated with perceived HPV vaccine benefits (r=0.51, p<0.001), anticipatory regret (r=0.27, p<0.001), perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (r=0.19, p<0.001); and negatively correlated with fear of needles (r=−0.11, p<0.05) and fear of side effects (r=−0.09, p<0.01).

HPV vaccine endorsement: acceptability was positively correlated with HCP recommendation (r=0.42, p<0.01), supportive/accepting social environment for HPV vaccines (r=0.18, p<0.001) and negatively correlated with partner thinks one should get the vaccine (r=−0.41, p<0.001).

HPV risk perceptions: perceived risk or perceived susceptibility to HPV infection (r=0.25, p<0.001) and perceived HPV severity (r=0.09, p<0.001) were positively associated with acceptability.

Behavioural risk indicators: number of lifetime sexual partners (r=0.18, p<0.01), having a current sex partner (r=0.17, p<0.05), smoking cigarettes (r=0.12, p<0.05) and history of STI (r=0.10, p<0.05) were positively correlated with HPV vaccine acceptability. Non-receipt of hepatitis B vaccine was negatively correlated with acceptability (r=−0.16, p<0.001).

HPV awareness (ie, having heard about HPV) (r=0.17, p<0.01) and HPV knowledge (ie, correctly answering questions about HPV) (r=0.09, p<0.05) were positively associated with acceptability.

Structural barriers: vaccine cost (r=−0.17, p<0.001), logistical barriers (eg, hassle, time, transportation) (r=−0.16, p<0.05) and need for multiple shots/doses (r=−16, p<0.01) were negatively correlated with HPV vaccine acceptability.

Sociodemographic characteristics: being employed (r=0.13, p<0.05) and non-white (vs white) ethnicity (r=0.09, p<0.05) were positively associated with HPV vaccine acceptability. Educational level, included in the majority of studies examined, approached significance (r=0.08, p=0.05).

Perceived HPV vaccine benefits, anticipatory regret, HCP recommendation and partner thinks one should get vaccine had medium effect sizes on HPV vaccine acceptability (see table 2), based on Cohen's classification.57 The remaining correlates had low effect sizes.

Discussion

This meta-analysis reveals a moderate level of HPV vaccine acceptability among men (50.4 on a 100-point scale) across 22 studies totalling 8360 participants, with a wide range of acceptability (8.2–94.0) across studies. In contrast, acceptability was considerably higher (55.0–100.0) in a review of US studies focused on young women,26 although mean acceptability was not reported.

Meta-analysis results across 16 studies (n=5048) indicate the influence of positive HPV vaccine attitudes, HCP recommendation, perceived HPV risk and HPV awareness and knowledge on HPV vaccine acceptability for men. Health promotion messaging that fosters positive attitudes about HPV vaccination benefits for men, accurate HPV risk perceptions, and that enhances awareness and knowledge regarding HPV may increase the acceptability of HPV vaccination for men.

We found no significant difference in HPV vaccine acceptability between gay, bisexual and other MSM, who would benefit most from HPV4 vaccination,7 8 and heterosexual men. Results from the meta-analysis suggest that in addition to promoting HPV4 vaccination for all boys and young men,23 25 48 51 targeted messaging for young MSM to support perceived HPV vaccine benefits and effectiveness, and accurate perceptions of HPV risk may increase acceptability.

HCP recommendation, the correlate with the second highest impact on HPV vaccine acceptability after perceived HPV vaccine benefits, has been identified as an important factor in HPV vaccine acceptability for girls,26 and patient acceptance of hepatitis B vaccines.58 HCP-identified barriers to hepatitis B vaccination—lack of government reimbursement, patient non-disclosure of risk and inadequate time to assess risk59—suggest that in addition to promoting HCP recommendation of HPV4 vaccination for boys, it is important to assess systemic and structural barriers that may impede HCP recommendation.

The impact of HPV risk perceptions, awareness and knowledge on HPV vaccine acceptability is notable given evidence of low levels of HPV knowledge and awareness among men.32 50 60 Mechanisms to foster accurate HPV risk perceptions and awareness might involve addressing the prevalence of HPV infection and its association with cancers among men, highlighting cancer prevention as a benefit of HPV vaccination for boys48 and challenging false beliefs that HPV vaccines are not relevant for men.25

Notably, out-of-pocket cost, as reported in earlier reviews,22 23 25 logistical barriers and the need for a series of injections were negatively associated with acceptability. In meta-analysis these structural barriers had a greater impact than HPV vaccine knowledge (the most often studied correlate) and effect sizes equal to behavioural risk factors. In addition to tailored educational interventions government financing of HPV4 vaccination, and interventions to reduce barriers in access to vaccination may significantly increase HPV4 vaccine acceptance among men.

Finally, further research is needed to explore the negative association between partner thinks one should get the HPV vaccine and HPV vaccine acceptability, based on only two studies.24 44 Partner endorsement might implicate stigma and the association of HPV as a women's disease.25

Limitations to this meta-analysis include the absence of intervention studies, the relatively small number of studies and exclusion of unpublished studies, with few studies from each of several countries outside the USA. The lack of intervention studies precludes using RevMan 5 for meta-analyses; and some correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability are based on few studies. The limited number of studies in each setting precludes subanalysis by country. Additional studies overall and within each setting will help to identify possible differences in acceptability, including by healthcare systems and culture. Two studies of parental acceptance of HPV vaccines for male adolescents were included in the calculation of mean acceptability though not included in meta-analysis; given different challenges to uptake for adolescents and adults, meta-analysis of parental acceptance of HPV vaccination for boys is indicated.

Another limitation is due to the high risk of bias among the majority of studies included in the meta-analysis; this is indicative of weak study designs (ie, cross-sectional, non-random sampling) and suggests caution in generalising the results. However we used a random effects model that takes into account between-study and within-study variability, which suggests that the effect sizes approximate an appropriate mean of a distribution of effects. This meta-analysis provides a quantitative synthesis of the literature, indicating correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability and the magnitude and direction of these associations among a large sample of men across different studies.

Finally, as most of the studies reviewed were conducted before the US Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices recommended routine HPV4 vaccination of men, levels and correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability may shift with additional post-2011 studies. However, low HPV vaccine coverage among young women in the USA and Europe since licensure in 200610 18 suggests the importance of synthesising available evidence on acceptability to guide evolving policy recommendations.

This meta-analysis suggests the importance of future investigations using more rigorous designs, including intervention research, to address factors that promote HPV vaccine acceptability among men. Generally lower levels of support for HPV vaccination among HCP and parents for young boys versus young girls11 25 and the particular need for HPV4 vaccination in gay/bisexual/MSM, indicate the importance of routinely disaggregating data by sex and sexual orientation in future investigations of HPV vaccine acceptability.

Overall, the moderate level of vaccine acceptability among men in the case of HPV, the most common STI, supports the need for evidence-informed interventions to address widespread gaps between HPV vaccine recommendations and actual use.

Key messages.

A moderate level of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability (50.4 on a 100-point scale) was reported among 8360 men across 22 studies.

Perceived HPV vaccine benefits and healthcare provider recommendation were the two most influential correlates of HPV vaccine acceptability among men.

HPV vaccine cost and logistical barriers may pose significant obstacles to uptake.

HPV vaccination campaigns targeting men should promote awareness of HPV, HPV-associated cancer risks and HPV vaccine efficacy, and healthcare providers’ recommendation of HPV vaccination for boys.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Handling editor Jackie A Cassell.

Contributors: PAN conceptualised the study, contributed to data analysis and led writing of the manuscript. CHL, KA and ND reviewed titles and abstracts for inclusion in the review, read the articles and reviewed the manuscript. CHL conducted meta-analysis and drafted the methods and results.

Funding: This research was funded in part by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (funding reference number THA-118570) through the Canadian HIV Vaccine Initiative, and the Canada Research Chairs program (950-204522).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is HPV? http://www.cdc.gov/hpv/WhatIsHPV.html (accessed 24 Apr 2013)

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and men: questions and answers. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts/hpv-vph/hpv-vph-man-eng.php (accessed 24 Apr 2013)

- 3.Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Efirdc JT, et al. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS 2005;19:1407–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstone S, Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection among HIV-seronegative men who have sex with men. J Infect Dis 2011;203:66–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyitray AG, da Silva RJC, Baggio ML, et al. Age-specific prevalence of and risk factors for anal human papillomavirus (HPV) among men who have sex with women and men who have sex with men: the HPV in men (HIM) study. J Infect Dis 2011;203:49–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection. http://www.cdc.gov/std/HPV/STDFact-HPV.htm#common (accessed 29 Apr 2013)

- 7.Frisch M, Glimelius B, van den Brule AJ, et al. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. N Eng J Med 1997;337:1350–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frisch M, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in human with human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndromes. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1500–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiter PL, Brewer NT, Smith JS. Human papillomavirus knowledge and vaccine acceptability among a national sample of heterosexual men. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:241–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males–Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6050a3.htm (accessed 24 Apr 2013)

- 11.Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med 2011;364:401–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Eng J Med 2011;365:1576–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castle PE, Zhao FH. Population effectiveness, not efficacy, should decide who gets vaccinated against human papillomavirus via publicly funded programs. J Infect Dis 2011;204:335–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brisson M, van de Velde N, Franco EL, et al. Incremental impact of adding boys to current human papillomavirus vaccination programs: role of herd immunity. J Infect Dis 2011;204:372–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:244–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JJ, Goldie SJ. Cost effectiveness analysis of including boys in a human papillomavirus vaccination programme in the United States. BMJ 2009;339:b3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Public Health Agency of Canada. Update on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines: recommendations. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/12vol38/acs-dcc-1/index-eng.php#a5 (accessed 29 Apr 2013)

- 18.Australian Cancer Research Foundation. World-first HPV vaccination plan will protect young Australian men from cancer. http://acrf.com.au/2012/world-first-hpv-vaccination-plan-will-protect-young-australian-men-from-cancer/ (accessed 24 Apr 2013)

- 19.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Stemming cervical cancer: European agency calls for more HPV vaccinations. http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/european-agency-recommends-hpv-vaccine-for-all-girls-a-854323.html (accessed 24 Apr 2013)

- 20.Marty R, Roze S, Bresse X, et al. Estimating the clinical benefits of vaccinating boys and girls against HPV-related diseases in Europe. BMC Cancer 2013;13:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JJ. Targeted human papillomavirus vaccination of men who have sex with men in the USA: a cost-effectiveness modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:845–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stupiansky NW, Alexander AB, Zimet GD. Human papillomavirus vaccine and men: what are the obstacles and challenges? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012;25:86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL. HPV vaccine and males: issues and challenges. Gynecol Oncol 2010;117:S26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferris DG, Waller JL, Miller J, et al. Variables associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptance by men. J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liddon N, Hood J, Wynn BA, et al. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine for males: a review of the literature. Journal of Adolescent Health 2010;46:113–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med 2007;45:107–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:ee1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas H. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/view/eng/14.html (accessed 29 Apr 2013)

- 29.Rand CM, Schaffer SJ, Humiston SG, et al. Patient-provider communication and human papillomavirus vaccine acceptance. Clin Pediatr 2011;50:106–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daley EM, Marhefka SL, Buhi ER, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine intentions among men participating in a human papillomavirus natural history study versus a comparison sample. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:644–52 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daley EM, Marhefka SL, Buhi ER, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in HPV knowledge and vaccine intentions among men receiving HPV test results. Vaccine 2011;29:4013–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert P, Brewer NT, Reiter PL, et al. HPV vaccine acceptability in heterosexual, gay, and bisexual men. Am J Mens Health 2011;5:297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbert PA, Brewer NT, Reiter PL. Association of human papillomavirus-related knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs with HIV status: a national study of gay men. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2011;15:83–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheldon CW, Daley EM, Buhi ER, et al. Health beliefs and attitudes associated with HPV vaccine intention among young gay and bisexual men in the southeastern United States. Vaccine 2011;29:8060–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrovic K, Burney S, Fletcher J. The relationship of knowledge, health value and health self-efficacy with men's intentions to receive the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. J Health Psychol 2011;16:1198–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young AP, Crosby RA, Jagger KS, et al. Influences on HPV vaccine acceptance among men in the Philippines. J Men's Health 2011;8:126–35 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blödt S, Holmberg C, Müller-Nordhorn J, et al. Human papillomavirus awareness, knowledge and vaccine acceptance: a survey among 18–25 year old male and female vocational school students in Berlin, Germany. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:808–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bynum SA, Brandt HM, Friedman DB, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors: examining human papillomavirus-related gender differences among African American college students. J Am Coll Health 2011;59:296–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chelimo C, Wouldes TA, Cameron LD. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptance and perceived effectiveness, and HPV infection concern among young New Zealand university students. Sex Health 2010;7:394–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, et al. Gardasil for guys: correlates of intent to be vaccinated. J Mens Health 2011;8:119–25 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferris DG, Waller JL, Miller J, et al. Men's attitudes towards receiving the human papillomavirus vaccine. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2008;12:276–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerend MA, Barley J. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among young adult men. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gottvall M, Larsson M, Hoglund AT, et al. High HPV vaccine acceptance despite low awareness among Swedish upper secondary school students. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2009;14:399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Thompson PS, et al. Acceptability of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccination among adult men. Hum Vaccin 2010;6:467–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones M, Cook R. Intent to receive an HPV vaccine among university men and women and implications for vaccine administration. J Am Coll Health 2008;57:23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenselink CH, Schmeink CE, Melchers WJG, et al. Young adults and acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Public Health 2008;122:1295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall H, Ryan P, Roberton D, et al. A cross-sectional survey to assess community attitudes to introduction of human papillomavirus vaccine. Aust NZ J Public Health 2007;31:235–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McRee A, Reiter PL, Chantala K, et al. Does framing human papillomavirus vaccine as preventing cancer in men increase vaccine acceptability? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1937–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oh J, Lim MK, Yun EH, et al. Awareness of and attitude towards human papillomavirus infection and vaccination for cervical cancer prevention among adult males and females in Korea: a nationwide interview survey. Vaccine 2010;28:1854–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pitts M, Smith A, Croy S, et al. Singaporean men's knowledge of cervical cancer and human papillomavirus (HPV) and their attitudes towards HPV vaccination. Vaccine 2009;27:2989–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reiter PL, Brewer NT, McRee AL, et al. Acceptability of HPV vaccine among a national sample of gay and bisexual men. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:197–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sauvageau C, Duval B, Gilca V, et al. Human papilloma virus vaccine and cervical cancer screening acceptability among adults in Quebec, Canada. BMC Public Health 2007;7:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simatherai D, Bradshaw CS, Fairley CK, et al. What men who have sex with men think about the human papillomavirus vaccine. Sex Transm Infect 2009;85:148–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sundstrom K, Tran TN, Lundholm C, et al. Acceptability of HPV vaccination among young adults aged 18–30 years–a population based survey in Sweden. Vaccine 2010;28:7492–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas EA, Goldstone SE. Should I not shouldn't I: Decision making, knowledge and behavioral effects of quadrivalent HPV vaccination in men who have sex with men. Vaccine 2011;29:570–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samoff E, Dunn A, Vandevanter N, et al. Predictors of acceptance of hepatitis B vaccination in an urban sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Sex Transm Dis 2004;31:415–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daley MF, Hennessey KA, Weinbaum CM, et al. Physician practices regarding adult hepatitis B vaccination: a national survey. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:491–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newman PA, Roberts KJ, Masongsong E, et al. Anal cancer screening: barriers and facilitators among ethnically diverse gay, bisexual, transgender, and other men who have sex with men. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 2008;20:328–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]