Abstract

Background

Stickler syndromes types 1, 2 and 3 are usually dominant disorders caused by mutations in the genes COL2A1, COL11A1 and COL11A2 that encode the fibrillar collagens types II and XI present in cartilage and vitreous. Rare recessive forms of Stickler syndrome exist that are due to mutations in genes encoding type IX collagen (COL9A1 type 4 Stickler syndrome and COL9A2 type 5 Stickler syndrome). Recently, recessive mutations in the COL11A1 gene have been demonstrated to result in fibrochondrogenesis, a much more severe skeletal dysplasia, which is often lethal. Here we demonstrate that some mutations in COL11A1 are recessive, modified by alternative splicing and result in type 2 Stickler syndrome rather than fibrochondrogenesis.

Methods

Patients referred to the national Stickler syndrome diagnostic service for England, UK were assessed clinically and subsequently sequenced for mutations in COL11A1. Additional in silico and functional studies to assess the effect of sequence variants on pre-mRNA processing and collagen structure were performed.

Results

In three different families, heterozygous COL11A1 biallelic null, null/missense or silent/missense mutations, were found. They resulted in a recessive form of type 2 Stickler syndrome characterised by particularly profound hearing loss and are clinically distinct from the recessive types 4 and 5 variants of Stickler syndrome. One mutant allele in each family is capable of synthesising a normal α1(XI) procollagen molecule, via variable pre-mRNA processing.

Conclusion

This new variant has important implications for molecular diagnosis and counselling families with type 2 Stickler syndrome.

Keywords: Stickler syndrome, Recessive Inheritance, Alternative Splicing

Introduction

Type XI collagen along with type II collagen, forms the heterotypic fibrillar collagen fibrils found in cartilage and vitreous. It is a heterotrimer, encoded by three genes COL11A1 (MIM 120280), COL11A2 (MIM 120290) and COL2A1 (MIM 120140),1–7 the latter also encodes the homotrimer type II collagen that constitutes the major component of these collagen fibrils. Although type XI collagen is a quantitatively minor component of the fibrils it has an important role in regulating fibrillogenesis.8 Mutations of all three genes can result in different types of Stickler syndrome (MIM 108300, 604841, 184840),9–11 which is usually an autosomal dominant disorder with variable phenotype that includes myopia, retinal detachment, premature osteoarthritis, hearing loss, facial dysmorphism and midline clefting that can manifest as Pierre Robin sequence, or an isolated cleft palate.12 The COL11A2 gene is not expressed in the eye and mutations in that gene do not result in an eye phenotype.13 A recessive form of Stickler syndrome (MIM 614134, 614284)14 15 has been reported in association with null alleles of type IX collagen genes (COL9A1 MIM 120210 and COL9A2 MIM 120260). Type IX collagen connects heterotypic type II/XI collagen fibrils to other components of the extracellular matrix.16 17

A recent systematic review of published information on hearing loss in Stickler syndrome18 concluded that more than half of all patients have some form of hearing loss, but that this may vary between the different types. Hearing loss is usually mild to moderate, however when associated with COL11A1 and COL11A2 it is more common, more severe and presents at a younger age than for COL2A1. In the recessive forms, due to mutations in type IX collagen, the hearing loss is variable and has been described as mild to severe.14 15

The recessive disorder fibrochondrogenesis (MIM 228520), which is usually lethal, has also been shown to be due to mutations in COL11A1.19 20 In that disorder the mutations are either a combination of null alleles and missense mutations or biallelic null alleles. The carrier parents showed only mild clinical features such as myopia or hearing loss and were not considered to have Stickler syndrome.

COL11A1, COL11A2 and COL2A1 are all subject to alternative splicing,21 22 where inclusion or exclusion of exons encoding the N-propeptide region of the molecules results in isoforms that can vary in their interaction with other components of the extracellular matrix23 and growth factors such as TGFβ1 and BMP-2.24 As previously demonstrated, mutations in the alternatively spliced exon 2 of COL2A1 result in a non-systemic (or predominantly ocular) form of type 1 Stickler syndrome25 (MIM 609508). Here we demonstrate that mutations, in two families, affecting the alternatively spliced exon 9 (also referred to as exon 8 or variable region 2)26 27 of COL11A1 which is not expressed in cartilage,28 are modified by the natural alternative splicing that occurs in this gene. Both cases have a second mutation, but the combination of the two results in a recessive form of type 2 Stickler syndrome with profound hearing loss, rather than the more severe fibrochondrogenesis. In addition, we describe a third family with recessive type 2 Stickler syndrome that have a silent mutation which is variably spliced and able to express at least some normal α1(XI) collagen.

Materials and methods

Three families referred to the national Stickler syndrome diagnostic service for England were assessed clinically and with informed written consent, subsequently screened for mutations in COL11A1. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee.

Gene analysis

The COL11A1 gene was analysed by amplification and sequencing of all exons as previously described.29 In addition, possible regions of gene deletion/duplication were examined by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification using commercially available probes (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). The cDNA numbering is derived from the COL11A1 transcript NM_001854.3. The exons are numbered 1–68 as described in the reference sequences (NM_001854.3, NM_080692.2 and NM_080693.3), where exons 6, 7 and 9 are alternatively spliced, rather than numbered as exons 1–67 as in Annunen et al27 Transcript NM_001854.3 contains exons 6 and 9 (also referred to as exon 6A and 8, respectively) but not exon 7 (also referred to as exon 6B).

Mutation analysis

The effect of sequence variants on pre-mRNA processing was assessed in silico and functionally. Functional studies were performed using either minigenes as splicing reporters or cultured cells obtained from a heterozygous carrier. The minigene system USR1330 consisted of a cassette of four exons (43–46) from the COL2A1 gene into which a test exon could be inserted to obtain normal and variant hybrid minigene constructs. These could then be expressed in cultured mammalian cells. Cultured dermal fibroblasts obtained from patients were incubated with and without emetine, an inhibitor of nonsense mediated decay (NMD). RNA prepared from either transfected or patients’ cells was analysed by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) as previously described.30

Sequence variations were analysed in silico, using Alamut V.2.0 (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France), a software package that uses four different programmes to predict the effect of variants on pre-mRNA splicing (as previously described)30 and three programmes to analyse the effect of amino acid changes on protein function. These are PolyPhen-2, sorting intolerant from tolerant (SIFT) and align Grantham variation Grantham deviation (GVGD), which are also freely available as separate stand alone utilities, (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/, http://sift.jcvi.org/, http://agvgd.iarc.fr/).

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA isolated from cultured cells of the carrier for the c.2607A>G, p.Ala869Ala was reverse transcribed with a gene specific primer and superscript II (Invitrogen, http://www.invitrogen.com). The relative amount of the G allele was compared with the expression of the A allele by quantitative PCR using primers located in exon 32 and 33 and fluorescently labelled cDNA probes specific for each allele. RNA from a normal individual was used as a positive control for the A allele and a negative control for the G allele. Each reaction was performed in triplicate and this was repeated three times. A chromo4 machine (BioRad, http://www.bio-rad.com) was used to measure the amount of fluorescence produced from each amplification reaction, and the Opticon-Monitor software (BioRad, http://www.bio-rad.com) was used to measure the relative difference in expression between the normal A and mutant G allele.

Results

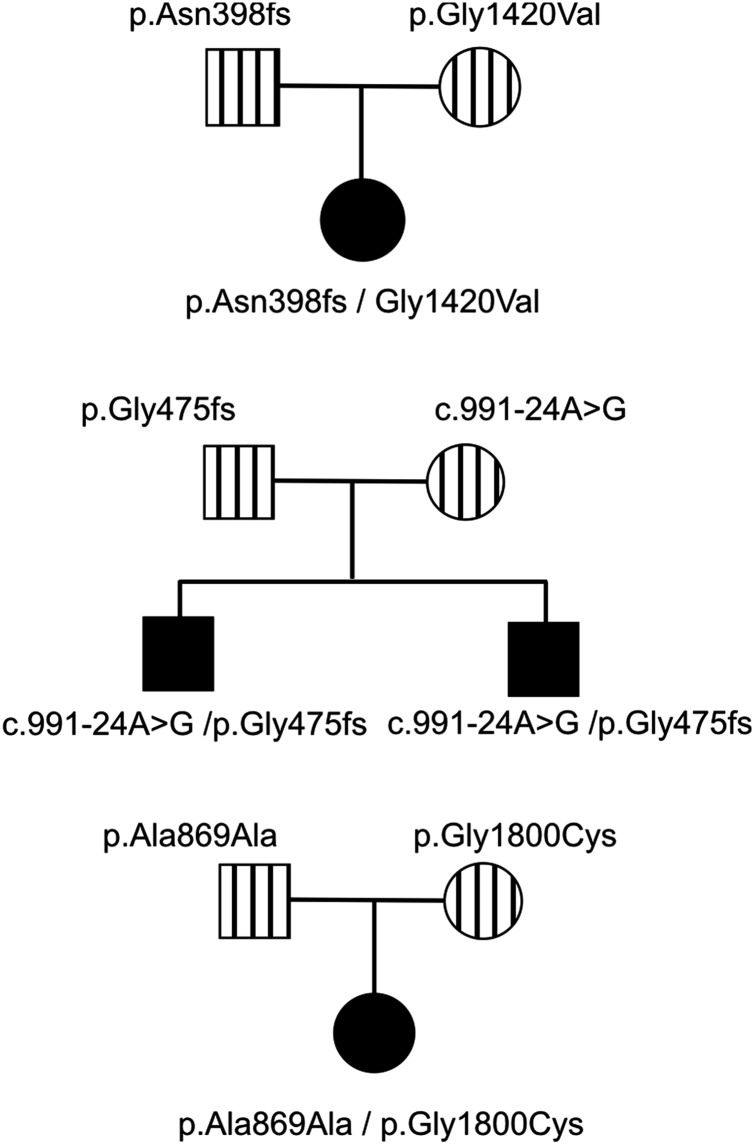

In each family, two unique mutations/variants were found as illustrated in figure 1 and online supplementary figure S1.

Figure 1.

Inheritance patterns of mutations. The pedigrees indicate the inheritance of each mutation in three different families. Solid squares/circles indicate individuals with type 2 Stickler syndrome. Vertical bars are carriers that had minor clinical signs associated with Stickler syndrome or a normal clinical appearance.

Family 1

The proband had been born with a cleft palate and subsequently found to be profoundly deaf with no recordable response from the left ear up to 100 dB and only a barely recordable response at 250 Hz/100 dB for the right ear. She communicates as an adult with sign language. Despite being hypermetropic (+3.50DS right, +4.50DS left) ophthalmological assessment revealed a hypoplastic vitreous gel architecture,29 without the membranous or beaded congenital vitreous anomaly. Assessment of her parents revealed insignificant, age-compatible sensorineural hearing loss for her mother (25 dB/4000 Hz) and mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss in her father (40 dB/1000–4000 Hz). Both parents had unremarkable vitreous architecture, exhibiting only mild age related vitreous syneresis. The pedigree is illustrated in figure 1.

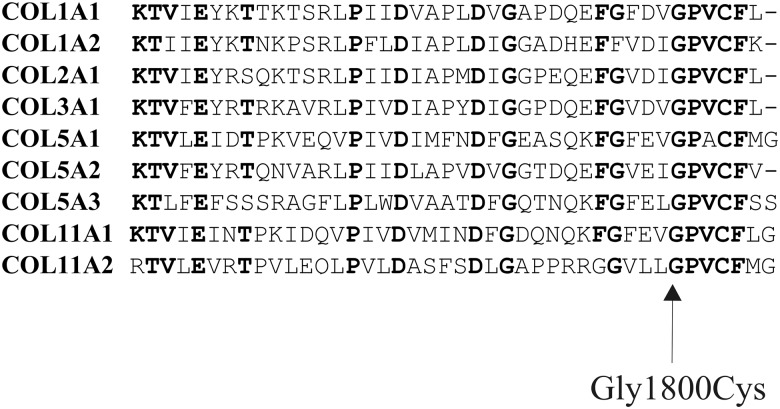

Mutations in exon 9 (c.1191delT, p.Asn398Metfs*19) and exon 58 (c.4259G>T, p.Gly1420Val) were found in the proband. Analysis of the parents’ DNA showed that the proband had inherited one mutation from each parent. The c.1191delT mutation has been previously reported, but erroneously located in exon 6 instead of exon 9.31 Because skipping of exon 9 would leave the message inframe and a functional collagen expressed, studies using RNA obtained from cultured dermal fibroblasts with the exon 9 mutation (c.1191delT) were used to assess whether any nonsense associated exon skipping resulted from this mutation. Cultured dermal fibroblasts which constitutively express the alternatively spliced exon 9 were treated with a nonsense mediated decay inhibitor. Amplification of cDNA (figure 2A), showed that the uninhibited cells produced a homozygous cDNA sequence which included exon 9, and since nonsense associated exon skipping would have resulted in a heterozygous sequence, this demonstrated that only the normal allele was expressed. Cells treated with the NMD inhibitor expressed both alleles, thereby confirming that the mutant allele would normally be naturally degraded by this cellular RNA quality surveillance system. However in tissues not expressing exon 9 the mutation would be naturally removed from the mature transcript. The p.Gly1420Val mutation disrupted the Gly-Xaa-Yaa amino acid repeat sequence of the collagen molecule, which is typical of pathogenic mutations in collagen molecules, and was predicted to be pathogenic by all three protein analysis tools in Alamut.

Figure 2.

Analysis of exon 9 mutations c.1191delT and c.991-24A>G by RT-PCR. RNA from a cell line heterozygous for the c.1191delT mutation was analysed by RT-PCR and sequenced (A). cDNA from cells incubated with emetine to inhibit NMD (−NMD) had the frameshift mutation, whereas cDNA from uninhibited cells (+NMD) had a homozygous sequence from the normal allele only. COL11A1 exon 9, including 682 bp of surrounding intron sequence, was amplified from genomic DNA containing the c.991-24A>G mutation (B). This was cloned into the splicing reporter USR13, between COL2A1 exons 44 and 45. Normal and mutant alleles were expressed in MIO-M1 cells, with the resulting RNA analysed by RT-PCR and sequencing (B). The variant cDNA had an additional 23 bp, which corresponded to the sequence from COL11A1 IVS8 and a de novo acceptor splice site created by the mutation. Green=A, red=T, blue=C, black=G.

Family 2

Two young boys, with severe and profound hearing loss, presented with parents who exhibited only mild clinical signs associated with Stickler syndrome, but were not considered to have the disorder. The proband was referred at age 20 months having been born with congenital high myopia (−7DS bilaterally), Pierre Robin sequence and profound hearing loss (90 dB), for which he had been treated with bilateral cochlear implants. His newborn brother (18 days old) also had Pierre Robin sequence and auditory brainstem assessment demonstrated no recordable responses at over 95 dB; typanometry was normal. Audiometry findings were confirmed on retesting and cochlear implants are planned. Their father had a high arched palate and mild, asymptomatic high tone hearing loss. The mother exhibited mild, asymptomatic hearing loss (35 dB/1000–2000 Hz); she also reported a history of hearing loss in her family. She had healthy compact vitreous gel architecture. The pedigree is illustrated in figure 1. Analysis of COL11A1 identified a frameshift mutation c.1421dupC, p.Gly475Argfs*9 in exon 13 and a sequence variant c.991-24A>G in intron 8 which was absent from the dbSNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) variation database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp). In silico analysis of this variant predicted that it created an alternative exon 9 acceptor splice site. It was also analysed functionally using minigenes, by cloning the normal and variant alleles into the splicing reporter USR13. This vector has been successfully used to assess other non-AG-GT splice site mutations that result in exon skipping and dominant type 2 Stickler syndrome (see online supplementary figure S2), including one (c.1845+5G>A) known to result in exon skipping in cultured cells.29 The normal and mutant minigenes produced a small amount of exon skipping, which reflected that this exon is alternatively spliced. However, the full length mutant cDNA appeared larger than the normal cDNA. This was confirmed by specifically amplifying and sequencing transcripts which included the 255 bp exon 9 (figure 2, see online supplementary figure S2B). The mutant transcript contained an insertion of an additional 23 bp at the start of exon 9 which corresponded to the creation of an acceptor splice site by the mutation, as predicted by in silico analysis. It caused a shift in the reading frame and a downstream premature termination codon. Despite the normal acceptor splice site being present, it was not used in the minigene experiments, as the sequence obtained from the variant clone was homozygous (figure 2B). Because exon 9 is not expressed in all tissues (NM_080630.3, transcript variant C) this mutation, like the c.1191delT mutation, would be naturally removed from transcripts in those tissues and have no effect.

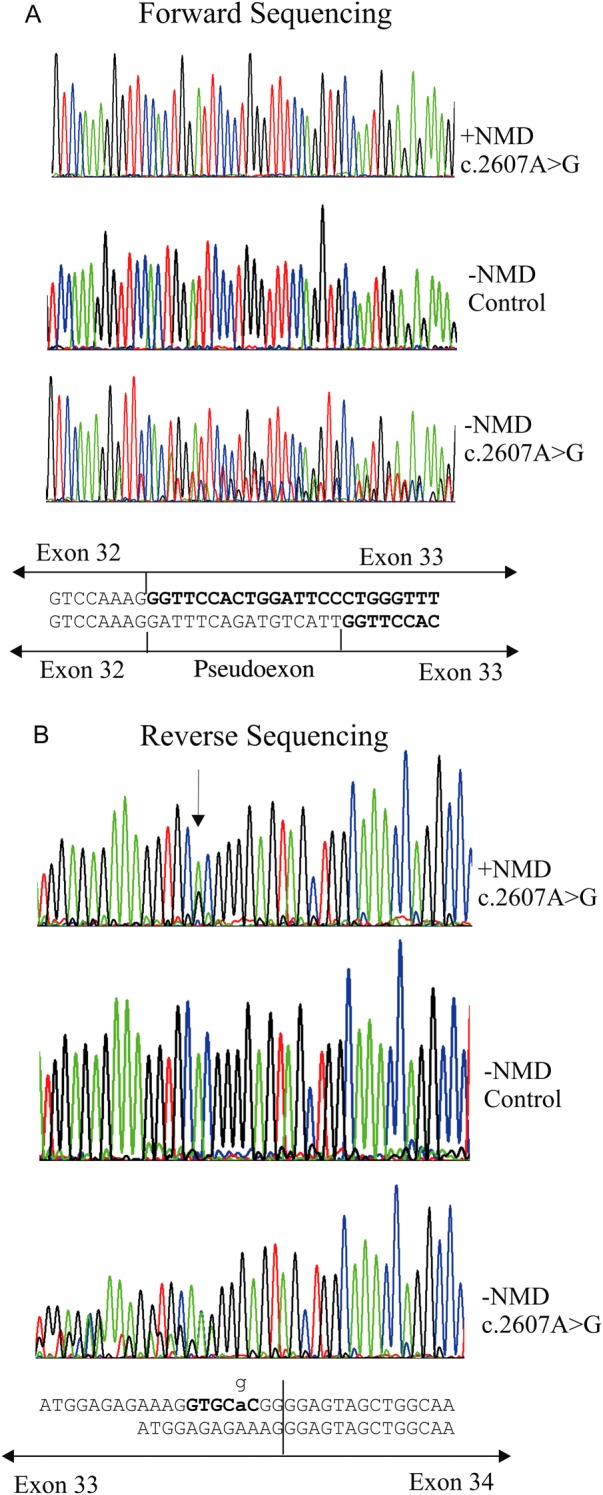

Family 3

The proband was a young girl (figure 3), born prematurely at 32 weeks and tube fed for 4 weeks, but without any evidence of a cleft palate. Hearing loss was diagnosed at 5 weeks of age, later being confirmed with pure tone audiometry which showed severe mixed conductive and sensorineural hearing loss from 250 Hz–8000 Hz with flat tympanometry. At 2 years of age concerns about visual development and a very pale fundal reflex led to referral for investigation of a possible retinal dystrophy. Refraction under cycloplegia revealed high myopia (−12:50DS right, −12:50DS left) and slit-lamp examination noted the type 2 beaded vitreous anomaly, associated with mutations in COL11A1.29 Despite the high refractive error, the discs were of normal size and configuration. A clinical diagnosis of probable type 2 Stickler syndrome was made. Full field electroretinogram, pattern reversal visual evoke potential and flash visual evoke potential were normal. Both parents exhibited healthy compact vitreous gel architecture and no evidence of hearing loss on audiology testing. The proband exhibited clinical joint laxity, but with no evidence of dysplastic changes of the hips or pelvis visible on radiology. Analysis of COL11A1 identified a silent variant c.2607A>G, p.Ala869Ala and a missense alteration c.5398G>T, p.Gly1800Cys. Both of these changes are novel and were absent from the dbSNP variation database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp). Analysis of the parents’ DNA showed that the silent variant was inherited from the father and the missense change from the mother. Analysis in silico predicted that the silent DNA variant created a donor splice site within exon 33 and also a potential binding site for the splicing factor SRp55. Using RNA obtained from the father's cultured dermal fibroblasts, RT-PCR demonstrated three splice isoforms (figure 4). First, RNA from cells uninhibited for NMD had the normal and variant sequence, demonstrating that the variant allele could be spliced normally, although there appeared to be unequal peak heights in the sequence chromatogram (figure 4). Using RNA from cells where NMD was inhibited, the use of the variant sequence as a donor splice site was observed by sequencing in the reverse direction, confirming the in silico prediction. In addition to the variant creating a donor splice site in the exon, sequencing in the forward direction also identified insertion of 16 nucleotides between exons 32 and 33. An examination of intron 32 showed that the inserted sequence was present at c.2557–186 to −171, it was preceded by a cag sequence and followed by the sequence gtaagt, which matched consensus acceptor and donor splice sites, respectively. Therefore the inserted sequence represented a pseudoexon which was activated by the c.2607A>G variant. Both of the misspliced transcripts resulted in frameshifts and premature termination of translation, reducing the level of expression from the mutant G allele. Quantitative RT-PCR indicated that the expression of the G allele was approximately 42 ± 3.5% of the normal A allele (data not shown), meaning that the misspliced transcripts represented around 58% of transcripts from the G allele.

Figure 3.

Facial photographs of a child with recessive type 2 Stickler syndrome. The child has c.2607A>G, p.Ala869Ala and c.5398G>T, p.Gly1800Cys mutations in COL11A1. The p.Gly1800Cys was inherited from her mother who is also shown.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR analysis of the c.2607A>G, p.Ala869Ala mutation. Cultured cells from a heterozygous carrier were incubated with (−NMD) or without (+NMD) emetine to inhibit nonsense mediated decay. NMD was also inhibited in a normal cell line as a control. RNA was analysed by RT-PCR and sequenced in the forward (A) and reverse (B) directions. Text sequence represents the sequence seen in uninhibited cells (upper) and the additional sequence obtained from inhibited cells (lower). In (A) an additional sequence was located between exons 32 and 33 (in bold type), which corresponded to a pseudoexon in intron 32. In the reverse direction, the mutant sequence (arrowed) was present in cDNA from uninhibited (+NMD) cells. When nonsense mediated decay was inhibited an additional transcript was seen which corresponded to the use of the GTGCAC sequence (in bold) as a donor splice site.

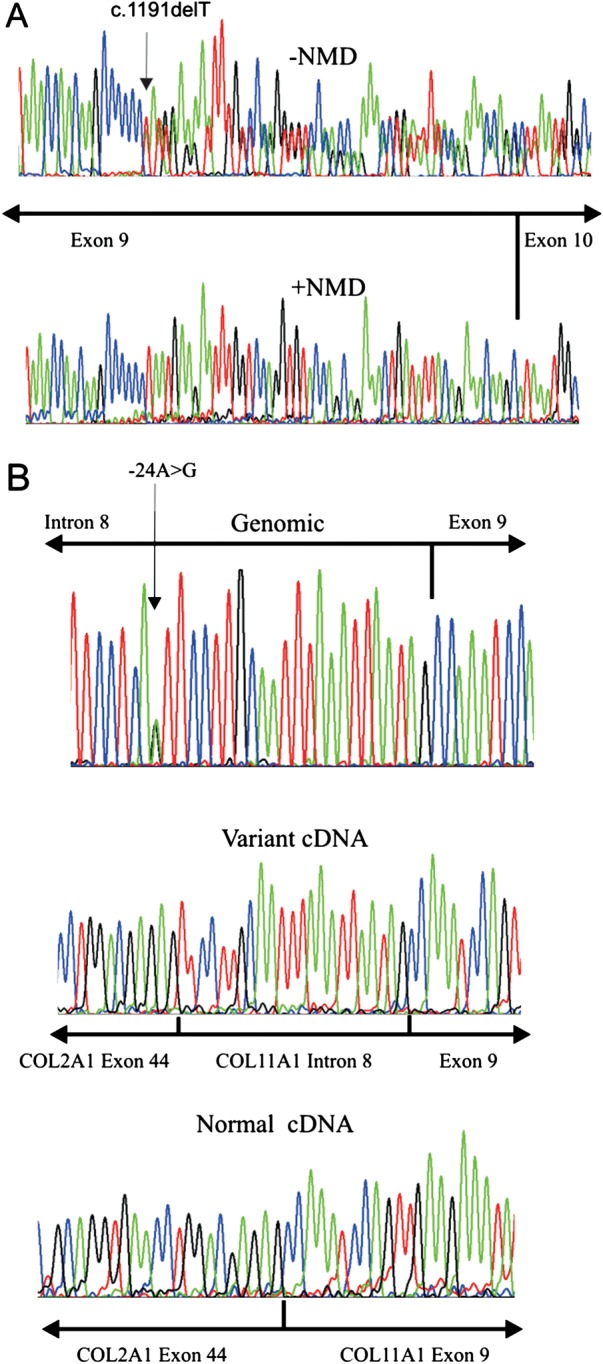

The missense change inherited from the mother changed a conserved glycine to cysteine in the C-propeptide region of the molecule (figure 5). Disruption to the pattern of cysteines in the C-propeptide of collagen molecules has been found in various other collagenopathies32 and in silico analysis predicted that the amino acid change was damaging.

Figure 5.

Multiple sequence alignment of the C-termini of the fibrillar collagens. Amino acids identical in at least seven of the nine protein sequences are in bold type. The position of the p.Gly1800Cys mutation is indicated.

Discussion

Stickler syndrome is usually a dominant disorder due to mutations in the collagen genes COL2A1, COL11A1 and COL11A2. Although there are rare recessive forms, these have all been reported in consanguineous families where the mutations have been homozygous.14 15 31 33 Here we report three non-consanguineous families with a novel recessive form of type 2 Stickler syndrome, without consanguinity to assist interpretation of the sequence variants detected. In all three, the phenotype is different from that documented with recessive type IX collagen mutations14 15 and is characterised by unusually severe/profound hearing loss. In two children this required cochlea implants, while an adult patient communicates by sign language.

The majority of mutations that result in dominant type 2 Stickler syndrome have been found to affect consensus splice sites in the COL11A1 gene and result in exon skipping. Because of the nature of exons in collagen genes, which typically encode a complete set of Gly-Xaa-Yaa amino acid repeat sequences, such mutations result in shortened α1(XI) procollagens that exert a dominant negative effect upon normal gene products with which they coassemble. Other mutations alter obligate glycines that must occur at every third position in the 1014 residue collagen triple helical domain.

Further phenotypes associated with mutations in COL11A1 are Marshall syndrome and fibrochondrogenesis. Marshall syndrome is a differential diagnosis to type 2 Stickler syndrome, it results mainly from exon skipping mutations of COL11A1 and differs in the severity of facial features that may be present.27 Fibrochondrogenesis was first characterised molecularly by Tompson et al,19 who found heterozygous null alleles inherited along with a substitution of an obligate glycine on the second allele. Later Akawi et al20 characterised two families who both had biallelic null mutations. Here we have demonstrated how, due to alternative splicing, which can be either natural or pathogenic in origin, similar null/missense or biallelic null mutations result in Stickler syndrome rather than fibrochondrogenesis (table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of recessive mutations in families 1, 2 and 3

| Mutation | Effect | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Family 1 | ||

| c.1191delT, p.Asn398Metfs*19 | Premature termination of translation and NMD | Only affects transcripts containing exon 9 |

| c.4259G>T, p.Gly1420Val | Disrupts the collagen Gly-Xaa-Yaa helical domain |

Classical type of collagen mutation |

| Family 2 | ||

| c.991-24A>G | Creates cryptic acceptor splice site, premature termination of translation and NMD | Only affects transcripts containing exon 9 |

| c.1421dupC, p.Gly475Argfs*9 | NMD | Null allele |

| Family 3 | ||

| c.2607A>G, p.Ala869Ala | Normal and Missplicing, premature termination of translation and NMD | Reduces the level of expression from the mutant allele |

| c.5398G>T, p.Gly1800Cys | Disrupts pattern of C-propeptide cysteines | Known to be disruptive in other collagen C-propeptides. |

Exon 9/intron 8 mutations

The c.1191delT mutation seen in family 1 has been previously reported in a homozygous state,31 emphasising the recessive nature of this mutation. However, Alzahrani et al31 erroneously located the mutation in exon 6. As in family 1 the patient described by Alzahrani et al31 had hearing loss, cleft palate but not myopia, although vitreoretinal degeneration was present in both. Alzahrani et al suggested that the resulting Stickler phenotype questioned whether fibrochondrogensis was simply a case of COL11A1 deficiency, and failed to consider that in fact exon 9 is naturally alternatively spliced26–28 and that only transcripts expressing this exon (NM_001854.3, NM_080692.2 transcript variants A and B) will be affected. Whereas transcript variant C (NM_080693.3) expressed in cartilage will not be altered. The examples of recessive Stickler syndrome that we describe here demonstrate that their premise is likely to be incorrect, and that the recessive Stickler syndrome phenotype is more probably due to the ability to synthesise normal α1(XI) collagen molecules because the mutations are removed by naturally occurring alternative splicing.

The expression of COL11A1 exon 9 in rat long bones is similar to the expression of the long form of type II collagen, that contains the region encoded by exon 2 of COL2A1.34 Both are present in immature chondrocytes but disappear as these cartilage precursors differentiate and mature. This would explain why the resulting phenotype in these individuals presented as Stickler syndrome rather than fibrochondrogenesis. As with the mechanism that removes mutations in exon 2 from COL2A1 and results in a non-systemic form of Stickler syndrome,25 so the natural alternative splicing of COL11A1 exon 9 modifies the effect of the mutations, consequently the severity of abnormal skeletal development is reduced. However, this exon is expressed in Meckel's cartilage26 which gives rise to the malleus and incus of the inner ear, in addition to the anterior ligament of the malleus tympanic plate,35 which is likely to explain why there is a more severe hearing than skeletal phenotype in these patients.

Like the c.1191delT mutation the c.991-24A>G mutation in intron 8, seen in family 2, will only affect tissues that express exon 9. Although not obviously pathogenic a combination of functional minigene analysis, in silico analysis, absence from the variation sequence databases and inheritance patterns, together indicate the pathogenic nature of this mutation. The family with the c.991-24A>G mutation also had a frameshift c.1421dupC mutation, predicted to result in two null alleles, similar to the families described by Akawi et al,20 except that here one (c.991-24A>G) is modified by alternative splicing of exon 9, whereas those causing fibrochondrogenesis affect constitutive exons.

Glycine substitution

As with the cases of fibrochondrogenesis described by Tompson et al,19 one patient characterised here possesses similar null/missense mutations, but has Stickler syndrome instead. The missense mutation p.Gly1420Val was coinherited with a null allele due to a mutation (c.1191delT) in the alternatively spliced exon 9. The missense mutation was also present in the patient's mother who exhibited only age-related hearing loss and no other clinical signs usually associated with mutations of COL11A1. This may be surprising, however, in other fibrillar collagens the substitution of obligate glycines can result in a wide range of phenotypic severity from lethal to mild, with the genes for type I collagen and osteogenesis imperfecta being the most studied.36 To date only eleven glycine substitutions have been described in COL11A1, and so the range of possible resulting phenotypic variation is currently unknown and difficult to predict from any particular missense mutation. The heterozygous carriers of similar glycine substitutions described by Tompson et al19 were also not considered to have Stickler syndrome and presented with only mild phenotypes, such as myopia or hearing loss. It would therefore appear that as with the quantitatively major collagens such as type I and type II collagen, substitutions of an obligate glycine in α1(XI) collagen can result in a spectrum of phenotypes, some resulting in Stickler syndrome, while others may produce only subtle clinical features not recognised as that disorder. The report of recessive Marshall syndrome37 in a consanguineous family with a homozygous glycine substitution in α1(XI) collagen supports this conclusion. In heterozygous cases of recessive type 2 Stickler syndrome there is a risk that a glycine substitution may be mistaken for dominant mutation, and the recessive nature of the change overlooked.

Silent mutation

As has previously been seen in COL2A1 and type 1 Stickler syndrome,29 here a silent mutation in COL11A1 results in missplicing of the COL11A1 transcript. The silent c.2607A>G, p.Ala869Ala mutation in family 3 resulted in three different splice isoforms. First it was spliced normally, second the mutation created a de novo donor splice site (as predicted by in silico analysis) and third it also activated a pseudoexon in the preceding intron. Both of the misspliced isoforms resulted in premature termination of the message and were only detected after inhibition of nonsense mediated decay. The effect of this mutation is to reduce the level of expression of the mutant allele, without resulting in a null allele. Unlike in families 1 and 2, where naturally occurring alternative splicing removes the mutation from certain tissues, here it was variation caused by the mutation that modified the phenotype. It is possible that the proportion of the various isoforms may differ from tissue to tissue, depending upon the expression of transacting splicing factors, but this has not been investigated.

C-propeptide mutation

Family 3 also had a novel C-propeptide mutation, changing a conserved glycine residue and incorporating an extra cysteine into the C-propeptide. This domain of the fibrillar collagens has a highly conserved pattern of cysteine residues which are important in forming intramolecular and intermolecular disulphide bonds during the trimerisation process of a collagen molecule.38 39 Although mutations in the C-propeptide of other fibrillar collagens have been described, this is the first example of a C-propeptide mutation in α1(XI) collagen. In other collagens, mutations within this domain can produce a wide variety of phenotypes depending upon how they affect its folding and function.32 It is likely that this extra cysteine will disrupt this process, as do similar mutations, that also create additional cysteines in the C-propeptides of α1(I) and α1(II) collagens.40–42 Along with the silent mutation c.2607A>G, p.Ala869Ala, inherited from the father, they result in Stickler syndrome. Because the silent mutation can also be spliced normally, it is not clear what phenotype would result if this novel C-propeptide mutation had been inherited with a null allele.

In summary, the identification here of a recessive form of type 2 Stickler syndrome, associated with unusually profound hearing loss, highlights the necessity for a detailed examination of both parents and a detailed gene analysis. It should not be assumed that a glycine substitution in the α1(XI) collagen helix is dominant and the sole pathogenic cause of type 2 Stickler syndrome. Of the 77 type 2 Stickler patients, with characterised dominant mutations seen in our clinic, none had profound (ie, greater than 95 dB) hearing loss (unpublished data), which agrees with the recent review by Acke et al.18 In this respect, families 1 and 2 were distinctive in their profound hearing loss, which may be an indication that it is associated with a recessive mode of inheritance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the technical and scientific staff in the Regional Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Cambridge UK, for their assistance with the genetic analysis. We would also like to thank AGNSS (http://www.specialisedservices.nhs.uk).

Footnotes

Contributors: The patients were examined clinically and detailed family histories obtained by GSF, AM, BC, MML, ATM, AVP, and MPS. RNA studies were designed by AJR and performed by AJR and DH. In silico analysis was performed by AJR. The manuscript was written by AJR JDS and MPS, proof-read and edited by the other authors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Cambridge Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Web resources: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) http://www.omim.org

dbSNP database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp.

References

- 1.Burgeson RE, Hollister DW. Collagen heterogeneity in human cartilage: identification of several new collagen chains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1979;87:1124–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheah KS, Stoker NG, Griffin JR, Grosveld FG, Solomon E. Identification and characterization of the human type II collagen gene (COL2A1). Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1985;82:2555–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris NP, Bächinger HP. Type XI collagen is a heterotrimer with the composition (1α,2α,3α) retaining non-triple-helical domains. J Biol Chem 1987;262:11345–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard M, Yoshioka H, Rodriguez E, Van der Rest M, Kimura T, Ninomiya Y, Olsen BR, Ramirez F. Cloning and sequencing of pro-α1 (XI) collagen cDNA demonstrates that type XI belongs to the fibrillar class of collagens and reveals that the expression of the gene is not restricted to cartilagenous tissue. J Biol Chem 1988;263:17159–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura T, Cheah KS, Chan SD, Lui VC, Mattei MG, van der Rest M, Ono K, Solomon E, Ninomiya Y, Olsen BR. The human alpha 2(XI) collagen (COL11A2) chain. Molecular cloning of cDNA and genomic DNA reveals characteristics of a fibrillar collagen with differences in genomic organization. J Biol Chem 1989;264:13910–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayne R, Brewton RG, Mayne PM, Baker JR. Isolation and characterization of the chains of type V/type XI collagen present in bovine vitreous. J Biol Chem 1993;268:9381–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JJ, Eyre DR. Structural analysis of cross-linking domains in cartilage type XI collagen. Insights on polymeric assembly. J Biol Chem 1995;270:18865–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaschke UK, Eikenberry EF, Hulmes DJ, Galla HJ, Bruckner P. Collagen XI nucleates self-assembly and limits lateral growth of cartilage fibrils. J Biol Chem 2000;275:10370–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad NN, Ala-Kokko L, Knowlton RG, Jimenez SA, Weaver EJ, Maguire JI, Tasman W, Prockop DJ. Stop codon in the procollagen II gene (COL2A1) in a family with the Stickler syndrome (arthro-ophthalmopathy). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991;88:6624–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vikkula M, Mariman ECM, Lui VCH, Zhidkova NI, Tiller GE, Goldring MB, van Beersum SEC, de Waal Malefijt MC, Vandenhoogen FHJ, Ropers HH, Mayne R, Cheah KSE, Olsen BR, Warman ML, Brunner H. Autosomal dominant and recessive osteochondrodysplasias associated with the COL11A2 locus. Cell 1995;80:431–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards AJ, Yates JRW, Williams R, Payne SJ, Pope FM, Scott JD, Snead MP. A family with Stickler syndrome type 2 has a mutation in the COL11A1 gene resulting in the substitution of glycine 97 by valine in α1(XI) collagen. Hum Mol Genet 1996;5:1339–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snead MP, Yates JRW. Clinical and Molecular Genetics of Stickler syndrome. J Med Genet 1999;36:353–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunner HG, van Beersum SEC, Warman ML, Olsen BR, Ropers H-H, Mariman ECM. A Stickler syndrome gene is linked to chromosome 6 near the COL11A2 gene. Hum Mol Genet 1994;3:1561–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Camp G, Snoeckx RL, Hilgert N, van den Ende J, Fukuoka H, Wagatsuma M, Suzuki H, Smets RM, Vanhoenacker F, Declau F, Van de Heyning P, Usami S. A new autosomal recessive form of Stickler syndrome is caused by a mutation in the COL9A1 gene. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:449–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker S, Booth C, Fillman C, Shapiro M, Blair MP, Hyland JC, Ala-Kokko L. A loss of function mutation in the COL9A2 gene cause autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155:1668–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holden P, Meadows RS, Chapman KL, Grant ME, Kadler KE, Briggs MD. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein interacts with type IX collagen, and disruptions to these interactions identify a pathogenetic mechanism in a bone dysplasia family. J Biol Chem 2001;276:6046–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parsons P, Gilbert SJ, Vaughan-Thomas A, Sorrell DA, Notman R, Bishop M, Hayes AJ, Mason DJ, Duance VC. Type IX collagen interacts with fibronectin providing an important molecular bridge in articular cartilage. J Biol Chem 2011;286:34986–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acke FR, Dhooge IJ, Malfait F, De Leenheer EM. Hearing impairment in Stickler syndrome: a systematic review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tompson SW, Bacino CA, Safina NP, Bober MB, Proud VK, Funari T, Wangler MF, Nevarez L, Ala-Kokko L, Wilcox WR, Eyre DR, Krakow D, Cohn DH. Fibrochondrogenesis results from mutations in the COL11A1 type XI collagen gene. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87:708–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akawi NA, Al-Gazali L, Ali BR. Clinical and molecular analysis of UAE fibrochondrogenesis patients expands the phenotype and reveals two COL11A1 homozygous null mutations. Clin Genet 2012;82:147–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan MC, Sandell LJ. Differential expression of a cysteine-rich domain in the amino-terminal propeptide of type II (cartilage) procollagen by alternative splicing of mRNA. J Biol Chem 1990;265:10334–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhidkova NI, Justice SK, Mayne R. Alternative mRNA processing occurs in the variable region of the pro- α1(XI) and pro-α2(XI) collagen chains. J Biol Chem 1995;270:9486–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warner LR, Brown RJ, Yingst SM, Oxford JT. Isoform-specific heparan sulfate binding within the amino-terminal noncollagenous domain of collagen α1(XI). J Biol Chem 2006;281:39507–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Y, Oganesian A, Keene DR, Sandell LJ. Type IIA procollagen containing the cysteine-rich amino propeptide is deposited in the extracellular matrix of prechondrogenic tissue and binds to TGF-β1 and BMP-2. J Cell Biol 1999;144:1069–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richards AJ, Martin S, Yates JRW, Baguley DM, Pope FM, Scott JD, Snead MP. COL2A1 exon 2 mutations: Relevance to the Stickler and Wagner syndromes. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:364–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies GB, Oxford JT, Hausafus LC, Smoody BF, Morris NP. Temporal and spatial expression of alternative splice-forms of the alpha1(XI) collagen gene in fetal rat cartilage. Dev Dyn 1998;213:12–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Annunen S, Korkko J, Czarny M, Warman ML, Brunner HG, Kääriäinen H, Mulliken JB, Tranebjaerg L, Brooks DG, Cox GF, Cruysberg JR, Curtis MA, Davenport SL, Friedrich CA, Kaitila I, Krawczynski MR, Latos-Bielenska A, Mukai S, Olsen BR, Shinno N, Somer M, Vikkula M, Zlotogora J, Prockop DJ, Ala-Kokko L. Splicing mutations of 54-bp exons in the COL11A1 gene cause Marshall syndrome, but other mutations cause overlapping Marshall/Stickler phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet 1999;65:974–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui Y, Kimura T, Tsumaki N, Nakata K, Yasui N, Araki N, Hasimoto N, Uchida A, Ochi T. Splicing patterns of type XI collagen transcripts act as molecular markers for osteochondrogenic tumors. Cancer Lett 1998;124:143–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards AJ, McNinch A, Martin H, Oakhill K, Rai H, Waller S, Treacy B, Whittaker J, Meredith S, Poulson A, Snead MP. Stickler syndrome and the vitreous phenotype: mutations in COL2A1 and COL11A1. Hum Mut 2010;31:E1461–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards AJ, McNinch A, Whittaker J, Treacy B, Oakhill K, Poulson A, Snead MP. Splicing analysis of unclassified variants in COL2A1 and COL11A1 identifies deep intronic pathogenic mutations. Eur J Hum Genet 2012;20:552–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alzahrani F, Alshammari MJ, Alkuraya FS. Molecular pathogenesis of fibrochondrogenesis: is it really simple COL11A1 deficiency? Gene 2012;551: 480–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourhis JM, Mariano N, Zhao Y, Harlos K, Exposito JY, Jones EY, Moali C, Aghajari N, Hulmes DJ. Structural basis of fibrillar collagen trimerization and related genetic disorders. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012;19:1031–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nikopoulos K, Schrauwen I, Simon M, Collin RW, Veckeneer M, Keymolen K, Van Camp G, Cremers FP, van den Born LI. Autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome in two families is caused by mutations in the COL9A1 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4774–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris NP, Oxford JT, Davies GB, Smoody BF, Keene DR. Developmentally regulated alternative splicing of the α1(XI) collagen chain: spatial and temporal segregation of isoforms in the cartilage of fetal rat long bones. J Histochem Cytochem 2000;48:725–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung KS, Park HH, Ting K, Takita H, Apte SS, Kuboki Y, Nishimura I. Modulated expression of type X collagen in Meckel's cartilage with different developmental fates. Dev Biol 1995;170:387–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marini JC, Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, San Antonio JD, Milgrom S, Hyland JC, Körkkö J, Prockop DJ, De Paepe A, Coucke P, Symoens S, Glorieux FH, Roughley PJ, Lund AM, Kuurila-Svahn K, Hartikka H, Cohn DH, Krakow D, Mottes M, Schwarze U, Chen D, Yang K, Kuslich C, Troendle J, Dalgleish R, Byers PH. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum Mutat 2007;28:209–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khalifa O, Imtiaz F, Allam R, Al-Hassnan Z, Al-Hemidan A, Al-Mane K, Abuharb G, Balobaid A, Sakati N, Hyland J, Al-Owain M. A recessive form of Marshall syndrome is caused by a mutation in the COL11A1 gene. J Med Genet 2012;49:246–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dion AS, Myers JC. COOH-terminal propeptides of the major human procollagens. Structural, functional and genetic comparisons. J Mol Biol 1987;193:127–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lees JF, Bullied NJ. The role of cysteine residues in the folding and association of the COOH-terminal propeptide of types I and III procollagen. J Biol Chem 1994;269:24354–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bateman JF, Lamande SR, Hannagan M, Moeller I, Dahl HH, Cole WG. Chemical cleavage method for the detection of RNA base changes: experience in the application to collagen mutations in osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Med Genet 1993;45:233–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishimura G, Nakashima E, Mabuchi A, Shimamoto K, Shimamoto T, Shimao Y, Nagai T, Yamaguchi T, Kosaki R, Ohashi H, Makita Y, Ikegawa S. Identification of COL2A1 mutations in platyspondylic skeletal dysplasia, Torrance type. J Med Genet 2004;41:75–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoornaert KP, Vereecke I, Dewinter C, Rosenberg T, Beemer FA, Leroy JG, Bendix L, Björck E, Bonduelle M, Boute O, Cormier-Daire V, De Die-Smulders C, Dieux-Coeslier A, Dollfus H, Elting M, Green A, Guerci VI, Hennekam RC, Hilhorts-Hofstee Y, Holder M, Hoyng C, Jones KJ, Josifova D, Kaitila I, Kjaergaard S, Kroes YH, Lagerstedt K, Lees M, Lemerrer M, Magnani C, Marcelis C, Martorell L, Mathieu M, McEntagart M, Mendicino A, Morton J, Orazio G, Paquis V, Reish O, Simola KO, Smithson SF, Temple KI, Van Aken E, Van Bever Y, van den Ende J, Van Hagen JM, Zelante L, Zordania R, De Paepe A, Leroy BP, De Buyzere M, Coucke PJ, Mortier GR. Stickler syndrome caused by COL2A1 mutations: genotype-phenotype correlation in a series of 100 patients. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18:872–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.