Abstract

Background

Over 100 genes have been implicated in the aetiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). A detailed understanding of their independent and cumulative contributions to disease burden may help guide various clinical and research efforts.

Methods

Using targeted high-throughput sequencing, we characterised the variation of 10 Mendelian and 23 low penetrance/tentative ALS genes within a population-based cohort of 444 Irish ALS cases (50 fALS, 394 sALS) and 311 age-matched and geographically matched controls.

Results

Known or potential high-penetrance ALS variants were identified within 17.1% of patients (38% of fALS, 14.5% of sALS). 12.8% carried variants of Mendelian disease genes (C9orf72 8.78%; SETX 2.48%; ALS2 1.58%; FUS 0.45%; TARDBP 0.45%; OPTN 0.23%; VCP 0.23%. ANG, SOD1, VAPB 0%), 4.7% carried variants of low penetrance/tentative ALS genes and 9.7% (30% of fALS, 7.1% of sALS) carried previously described ALS variants (C9orf72 8.78%; FUS 0.45%; TARDBP 0.45%). 1.6% of patients carried multiple known/potential disease variants, including all identified carriers of an established ALS variant (p<0.01); TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) (n=2/2 sALS). Comparison of our results with those from studies of other European populations revealed significant differences in the spectrum of disease variation (p=1.7×10−4).

Conclusions

Up to 17% of Irish ALS cases may carry high-penetrance variants within the investigated genes. However, the precise nature of genetic susceptibility differs significantly from that reported within other European populations. Certain variants may not cause disease in isolation and concomitant analysis of disease genes may prove highly important.

Keywords: Genetic Epidemiology, Motor Neurone Disease

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a terminal neurodegenerative disease characterised by the degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons. Lifetime risk is approximately 1/4001 and in most instances an underlying cause cannot be established. Nonetheless, 22 genes have been implicated in Mendelian forms of the condition while a further 82 have been associated with disease risk (http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk).2

A detailed understanding of disease heterogeneity is important to facilitate appropriate stratification of subcohorts for clinical research purposes. However, the relative importance of identified ALS genes is largely unknown and to date the most comprehensive studies have analysed only six or seven disease-associated genes.3 4 Investigation of the cumulative effect of variation across distinct disease loci has also been limited, although a significant excess in the co-occurrence of putative disease variants among fALS patients has recently been demonstrated.5 There is also little known as to how the genetic aetiology of ALS varies across populations. Previous studies have suggested significant variability in the importance of specific disease genes,6 7 but these studies have involved comparisons of selected patient cohorts and no comparative study of population-based cohorts has yet been performed.

To establish the relative and cumulative frequencies of disease variants across 33 of the most well-established ALS-related genes, we analysed a population-based cohort of 444 Irish ALS cases and 311 age-matched and geographically matched controls by multiplexed targeted high-throughput sequencing. This represents the most extensive survey of ALS loci to date. To assess the importance of disease heterogeneity across populations, we compare our results with those reported by previous population-based studies of major disease genes. We also search for correlations in the co-occurrence of putative disease variants and investigate the importance of cumulative susceptibility across distinct disease loci.

Materials and methods

Study participants

All participating patients were recruited between 1999 and 2011 through the ALS Register of the Republic of Ireland or the ALS Register of Northern Ireland.8 All patients were of Irish ancestry and met the revised El Escorial criteria for possible, probable or definite ALS. Patients with an identifiable family history of ALS among first, second or third degree relatives were classified as ‘familial’, otherwise patients were classified as ‘sporadic’. Controls were neurologically normal at the time of blood donation and included the spouses of attending patients and volunteers recruited at primary care offices across the country. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants and the study was approved by the research and ethics committee in Beaumont Hospital, Dublin.

Targeted resequencing

Indexed paired-end Illumina sequencing libraries10 were prepared for 444 cases and 311 controls. Libraries were enriched for the coding exons of target genes using custom SureSelect kits (Agilent, Santa Clara, California, USA) and resequenced at either TrinSeq (Dublin, Ireland) or GATC Biotech (Konstanz, Switzerland). Generated sequencing reads were aligned to the GRCh37 build of the human genome using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) V.0.6.1.11 Subsequent quality control, depth of coverage analyses, power analyses, variant calling and variant annotation were performed using SAMtools V.0.1.18,12 the GATK V.2.1–2,13 Picard V.1.60 (http://picard.sourceforge.net/), Variant Effect Predictor V.2.7,14 Python V.2.7.3 (http://www.python.org/) and R V.2.14.1 (http://www.r-project.org/) along with the March 2012 release from the 1000 genomes project,15 the ESP6500 release from the NHLBI exome sequencing project (Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, Washington, USA (URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) (Accessed 18 July 2012)) and Ensembl 69.16 Further details on library preparation, target enrichment, sequencing and the analysis of sequence data are provided in the supporting materials and methods.

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise indicated, all statistical analyses were conducted in R V.2.14.1.

Evaluation of high-penetrance disease models

One-tailed binomial tests were used to assess whether the frequencies of variant carriers within a series of control cohorts were higher than could be accounted for under high-penetrance disease models.17 These control cohorts included an Irish panel (internal controls), a European panel (internal controls, the ESP6500—European American cohort, the 1000 genomes—European cohort) and a global panel (internal controls, the full ESP6500 cohort, the full 1000 genomes cohort). The expected carrier frequencies were taken as the product of patient carrier frequencies and the respective population risks for ALS (Irish 1/290; European 1/397; Global 1/397).1 High-penetrance disease models were rejected when the p value associated with any one of the three cohorts was <0.05. Carriers were defined as individuals homozygous for the variant allele for the evaluation of recessive disease models and individuals homozygous/ heterozygous for the variant allele for the evaluation of dominant disease models.

Analysis of variant co-occurrence

One-tailed binomial tests were used to explore whether the frequencies of cases carrying multiple splice site/non-synonymous ALS gene variants exceeded chance expectation. As per van Blitterswijk et al,5 the expected frequency of this occurrence was taken as (the number of cases carrying ≥1 variant/the total number of cases)*(the number of controls carrying ≥1 variant/ the total number of controls). Variants were excluded from these analyses, if the frequency of carriers among European/Global controls from the ESP6500 and 1000 genomes projects exceeded one of several potential critical values (see online supplementary tables S3 and S4 for details).

The frequency with which carriers of previously reported ALS variants also carried variants of additional Mendelian disease genes (3/43) was used to estimate the probability of observing multiple Mendelian disease gene variants among all identified carriers of a given ALS variant (ie, 33/33 C9orf72 hexanucleotide expansion carriers OR 2/2 TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) carriers OR 2/2 FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) carriers).

Analysis of population heterogeneity

The burden of putative disease variants across ANG, C9orf72, FUS, OPTN, SOD1 and TARDBP within the Irish and Italian ALS populations was compared first using c-alpha tests where singleton variants were collapsed into a single per locus count18 and second using allele count-based Fisher exact tests. To avoid artificial inflation of population differences due to biases in missing genotype rates, c-alpha test permutations were performed at each variant site independently.

Single variant association testing

Variants were tested for association with case–control status using PLINK V.1.07.19 Allelic, dominant and recessive disease models were tested using Fisher exact tests. Multiple testing correction was performed by the Westfall and Young permutation method. Synonymous variants were not considered in the correction of p values obtained from non-synonymous or splice site variants. Association tests were performed with and without sample filtering based on status for established disease mutations and a family history of ALS.

Results

Study participants

Four hundred and forty-four Irish ALS patients (57.7% men; mean age of onset=61.7±12.0 years; 65.4% spinal onset, 31.8% bulbar onset, 2.8% generalised onset) and 311 age-matched and geographically matched controls (47.2% men; mean age of sampling = 60.3±11.8 years) were included in the study. Fifty-three patients (11.9%) were recruited through the population-based Northern Irish ALS Register (Belfast, Northern Ireland) while the remaining 391 (88.1%) were recruited through the Irish ALS Register.8 Fifty patients (11.3%) were classified as ‘familial’ while 394 (88.7%) were classified as ‘sporadic’ according to recently published criteria.9 Twenty-four of the sporadic (6.1%) and 15 of the familial (30.0%) patients previously tested positive for pathogenic expansions of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat.20

Targeted resequencing

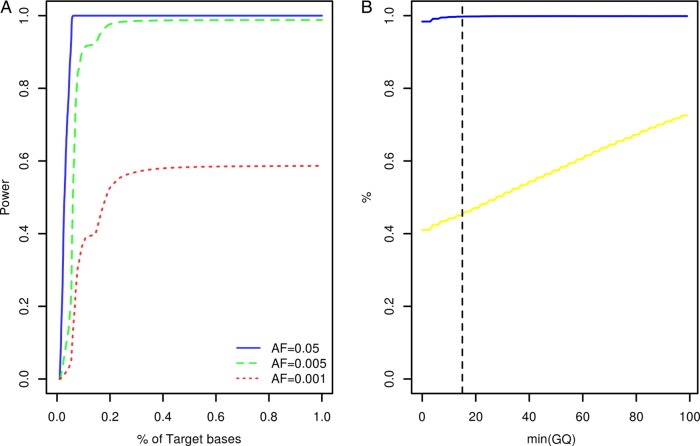

Study participants were screened for variants within the coding exons of 10 genes previously associated with Mendelian forms of ALS (ALS2, ANG, C9orf72, FUS, OPTN, SETX, SOD1, TARDBP, VAPB, VCP) and 23 low penetrance/tentative ALS genes (ATXN2, CHMP2B, DCTN1, DPP6, ELP3, FGGY, FIG4, GRN, HFE, IFNK, ITPR2, MAPT, MOB3B, NEFH, NIPA1, PARK7, PON1, PON2, PON3, PRPH, SIGMAR1, SPG11, UNC13A). At the time of target gene selection, the causative variant within the chromosome 9p linkage region had not been resolved and accordingly MOB3B and IFNK were included as tentative ALS genes.21 Given the large number of study participants and target exons involved, samples were resequenced using a multiplexed targeted high-throughput sequencing strategy.22 In total, 26.3×106 sequencing reads mapping to target positions were generated. Ninety-nine per cent of target bases were covered by at least 1 sequencing read and on an average each target position was covered by a mean of 27.3 sequencing reads per sample (see online supplementary table S1). Power to observe any variant with a patient allele frequency ≥0.5% was estimated to range from 0% to 98.8% across target positions with a median of 98.7% (IQR: 98.3–98.8%, figure 1A). A more detailed account of the distribution of variant detection power across target genes can be found in online supplementary figure S1. Four hundred and seventy-seven potential sequence variants were identified across target intervals (see online supplementary table S2). Ninety-five of these were designated as possible machine errors (see online supplementary materials and methods and table S2) and are not considered further. To evaluate the accuracy of genotypes inferred across the remainder of sites, genotypes called for 567 samples across 85 variants (target intervals ±50 bp) were compared with genotypes previously ascertained using Illumina HumanHap 550,23 Illumina Human610-Quad (deCODE Genetics, Reykjavik, Iceland) and Illumina OmniExpressExome-8v1 (Atlas Biolabs, Berlin, Germany) single nucleotide polymorphism BeadChip assays. This comparison revealed a genotype concordance rate of 98.9% among sequencing and BeadChip calls following genotype quality control (figure 1B, see online supplementary materials and methods).

Figure 1.

Target gene resequencing. (A) Cumulative density plot outlining the distribution of power to observe variants with patient allele frequencies of 0.05, 0.005 and 0.001. Power estimates were derived from the distribution of sequence coverage across target positions (see online supplementary materials and methods). (B) X-axis denotes the minimum sequencing genotype quality score (GQ) accepted for inference of sample genotypes across 85 variant sites. The blue line denotes the relationship between minimum GQ and the rate of concordance among sample genotypes ascertained by resequencing and sample genotypes ascertained using BeadChip assays. The yellow line denotes the relationship between minimum GQ and missing genotype rate among the sequencing call sets (n=567 samples). The vertical dotted line indicates the GQ threshold employed during this study (see online supplementary materials and methods). AF, allele frequency.

ALS-related variants

Based on the frequencies of carriers among internal controls and samples analysed by the NHLBI exome sequencing and 1000 genomes projects, all but 52 sequence variants were excluded as causing ALS with high penetrance (see the Methods section). Two of these represented previously described ALS variants; TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S])24–26; FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]).27 The remainder included 15 synonymous variants, 1 splice site variant (DCTN1:c.2887–2A>G), 20 missense variants classified as ‘deleterious’ by SIFT28 or ‘possibly/ probably damaging’ by PolyPhen29 and 14 missense variants classified as ‘tolerated’ by SIFT and ‘benign’ by PolyPhen. For the purpose of this study, all but the 15 synonymous variants were regarded as potentially disease causing. Seventy-six patients (38.0% of fALS, 14.5% of sALS, 17.1% of combined) carried either one of these potential disease variants or a previously described ALS variant, with 57 (34.0% of fALS, 10.2% of sALS, 12.8% of combined) carrying variants of Mendelian disease genes (table 1. C9orf72 39;SETX 11; ALS2 7; FUS 2; TARDBP 2; OPTN 1; VCP 1. ANG, SOD1, VAPB 0), 21 (6.0% of fALS, 4.6% of sALS, 4.7% of combined) carrying variants of low penetrance/tentative ALS genes (table 2. SPG11 7; ELP3 3; CHMP2B 2; DCTN1 2; MAPT 2; DPP6 1; FGGY 1; HFE 1; ITPR2 1; PON2 1; UNC13A 1. ATXN2, FIG4, GRN, IFNK, MOB3B, NEFH, NIPA1, PARK7, PON1, PON3, PRPH, SIGMAR1 0) and 43 (30.0% of fALS, 7.1% of sALS, 9.7% of combined) carrying a known ALS variant (table 1. C9orf72 39; FUS 2; TARDBP 2).

Table 1.

Putative disease variants of Mendelian ALS genes

| Gene | Variant | SIFT | PolyPhen | Model | fALS | sALS | IRL | EUR | GLO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS2* | c.3094C>T(p.[Arg1032Cys]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 0/49 | 1/375 | 0/274 | NR | NR |

| ALS2* | c.2606A>C(p.[Gln869Pro]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/390 | 0/290 | NR | NR |

| ALS2* | c.2566A>G(p.[Thr856Ala]) | Tolerated | Possibly damaging | D | 0/47 | 1/373 | 0/253 | NR | NR |

| ALS2* | c.2408A>G(p.[Lys803Arg]) | Tolerated | Possibly damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/391 | 0/289 | NR | NR |

| ALS2* | c.2098A>G(p.[Thr700Ala]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 2/386 | 0/279 | NR | NR |

| C9orf72 | Repeat expansion | – | – | D | 15/45 | 24/367 | 0/188 | NR | NR |

| FUS | c.1574C>T(p.[Pro525Leu]) | Deleterious | Possibly damaging | D | 0/43 | 2/319 | 0/250 | NR | NR |

| OPTN | c.1192C>G(p.[Gln398Glu]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 1/368 | 0/243 | NR | NR |

| SETX | c.7682C>T(p.[Ser2561Leu]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 2/358 | 0/253 | 1/4553 | 1/6756 |

| SETX | c.7645G>A(p.[Val2549Ile]) | Deleterious | Benign | D | 0/50 | 2/389 | 0/305 | 0/4605 | 1/6808 |

| SETX | c.5842A>G(p.[Met1948Val]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/388 | 0/279 | NR | NR |

| SETX | c.5587A>G(p.[Thr1863Ala]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 1/50 | 0/391 | 0/278 | NR | NR |

| SETX | c.2975A>G(p.[Lys992Arg]) | Deleterious | Benign | R | 1/50 | 0/388 | 0/280 | NR | NR |

| SETX | c.2842C>A(p.[Pro948Thr]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 1/50 | 0/387 | 0/282 | NR | NR |

| SETX | c.2755G>C(p.[Val919Leu]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 1/384 | 0/266 | NR | NR |

| SETX | c.814C>G(p.[His272Asp]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/387 | 0/280 | NR | NR |

| TARDBP | c.859G>A(p.[Gly287Ser]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 2/390 | 0/300 | NR | NR |

| VCP | c.2249A>G(p.[Asn750Ser]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 1/389 | 0/306 | NR | NR |

Variants previously associated with ALS are shown in bold.

*Gene conventionally associated with recessively inherited ALS.

D—Variant may cause disease in a dominant fashion and carrier frequencies relate to heterozygote carriers.

R—Variants may cause disease in a recessive fashion and carrier frequencies relate to homozygous carriers.

NR—Variant not reported within either the 1000 genomes or ESP6500 datasets (samples of European ancestry=4679, total number of samples=7595).

ALS2—ENST00000264276; FUS—ENST00000254108; OPTN—ENST00000263036; SETX—ENST00000224140; TARDBP—ENST00000240185; VCP—ENST00000358901.

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ESP, Exome Sequencing Project.

Table 2.

Putative disease variants of low penetrance/tentative ALS genes

| Gene | Variant | SIFT | PolyPhen | Model | fALS | sALS | IRL | EUR | GLO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHMP2B | c.118A>G(p.[Lys40Glu]) | Deleterious | Possibly damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/373 | 0/261 | NR | NR |

| CHMP2B | c.123G>T(p.[Gln41His]) | Deleterious | Possibly damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/373 | 0/263 | NR | NR |

| DCTN1 | c.2887-2A>G(p.?) | – | – | D | 0/39 | 2/239 | 0/246 | NR | NR |

| DPP6 | c.883G>A(p.[Glu295Lys]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/390 | 0/296 | NR | NR |

| ELP3 | c.206G>T(p.[Arg69Leu]) | Deleterious | Benign | D | 0/50 | 1/381 | 0/294 | NR | NR |

| ELP3 | c.326G>A(p.[Cys109Tyr]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 1/50 | 1/390 | 0/278 | 1/4578 | 1/6781 |

| FGGY | c.1716G>A(p.[Met572Ile]) | Tolerated | Possibly damaging | D | 0/48 | 1/376 | 0/285 | NR | NR |

| HFE | c.766G>A(p.[Val256Ile]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 1/388 | 0/295 | NR | NR |

| ITPR2 | c.3614G>A(p.[Arg1205Gln]) | Tolerated | Probably damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/371 | 0/266 | NR | NR |

| MAPT | c.284C>T(p.[Thr95Met]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/10 | 1/50 | 0/50 | 1/4349 | 1/6549 |

| MAPT | c.698C>T(p.[Pro233Leu]) | Tolerated | Probably damaging | D | 0/14 | 1/79 | 0/80 | NR | NR |

| PON2 | c.661T>G(p.[Ser221Ala]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/49 | 1/381 | 0/257 | NR | NR |

| SPG11* | c.7324G>C(p.[Ala2442Pro]) | Deleterious | Probably damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/391 | 0/282 | NR | NR |

| SPG11* | c.4343G>A(p.[Cys1448Tyr]) | Deleterious | Possibly damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/388 | 0/300 | NR | NR |

| SPG11* | c.3680A>G(p.[Lys1227Arg]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 1/50 | 0/390 | 0/302 | NR | NR |

| SPG11* | c.2577A>C(p.[Gln859His]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 1/380 | 0/267 | NR | NR |

| SPG11* | c.1930A>T(p.[Thr644Ser]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 1/49 | 0/382 | 0/265 | NR | NR |

| SPG11* | c.1529G>A(p.[Ser510Asn]) | Tolerated | Probably damaging | D | 0/50 | 1/389 | 0/282 | NR | NR |

| SPG11* | c.394A>G(p.[Ser132Gly]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/50 | 1/391 | 0/279 | NR | NR |

| UNC13A | c.3098T>A(p.[Val1033Asp]) | Tolerated | Benign | D | 0/49 | 1/372 | 0/286 | NR | NR |

D—Variant may cause disease in a dominant fashion and carrier frequencies relate to heterozygote carriers.

NR—Variant not reported within either the 1000 genomes or ESP6500 datasets (samples of European ancestry=4679, total number of samples=7595).

CHMP2B—ENST00000263780; DCTN1—ENST00000361874; DPP6—ENST00000377770; ELP3—ENST00000256398; FGGY—ENST00000371218; HFE—ENST00000357618; ITPR2—ENST00000381340; MAPT—ENST00000344290; PON2—ENST00000222572; SPG11—ENST00000261866; UNC13A—ENST00000519716.

*Gene conventionally associated with recessively inherited ALS.

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ESP, Exome Sequencing Project.

Patient phenotypes

Both patients carrying the TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) substitution were sporadic and presented with bulbar onset disease at 66/67 years of age. One patient remains alive at 51 months from disease onset, while the other died 49 months from disease onset. Both patients were cognitively intact. Both carriers of the FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) substitution were also sporadic. They exhibited an exceptionally young age of onset (13/21 years) and rapid disease progression (disease duration: 11–17 months). One patient experienced spinal onset disease while the other experienced bulbar onset. Both were cognitively intact. A detailed account of the phenotype exhibited by C9orf72 repeat expansion carriers has been provided previously.20 Further details on the phenotypes of all patients determined to carry known or possible disease variants are listed in online supplementary table S5.

Co-occurrences of ALS gene variants

Analysis of the number of cases carrying multiple rare or low-frequency variants revealed no detectable excesses across either the Mendelian genes alone or the entire dataset (see online supplementary tables S3 and S4). Seven patients (4.0% of fALS, 1.3% of sALS, 1.6% of combined) carried two variants classified as known or potential ALS variants in the previous analysis (online supplementary table S5). In the case of four of these individuals, both variants fell within Mendelian disease genes. Notably, these four individuals included both identified carriers of the TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S])) variant, who were observed to also carry either an ALS2:c.2566A>G(p.Thr856Ala) or an SETX:c.814C>G(p.His272Asp) substitution. The probability of such an observation for all carriers of any previously reported ALS variant was estimated to be less than 1%, suggesting that these co-occurrences may be pathologically meaningful. Other observed co-occurrences of putative disease variants included ALS2:c.2098A>G(p.Thr700Ala) and SETX:c.7682C>T(p.Ser2561Leu), the C9orf72 repeat expansion and CHMP2B:c.123G>T(p.Gln41His), the C9orf72 repeat expansion and SETX:c.2842C>A(p.Pro948Thr), the C9orf72 repeat expansion and SPG11:c.3680A>G(p.Lys1227Arg), the DCTN1:c.2887-2A>G splice acceptor site variant and SPG11:c.1529G>A(p.Ser510Asn). Further details on these patients can be found in online supplementary table S5.

Variation in the frequency of ALS variants across populations

To assess the potential importance of genetic heterogeneity across populations, we compared the estimated frequencies of ANG, C9orf72, FUS, OPTN, SOD1 and TARDBP disease variants among Irish patients with those reported by population-based studies of Italian cohorts.3 4 The difference was statistically significant (combined p=1.7×10−4, table 3), supporting a correlation between genetic susceptibility and population of origin. Of the 32 variants analysed, only the C9orf72 repeat expansion and the FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) substitution were observed among both Irish and Italian patients. The C9orf72 expansion was significantly more common among Irish patients (8.78% vs 4.39%, p=3.95×10−4) while SOD1 and TARDBP variants were significantly more common among Italian patients (SOD1: 2.00% vs 0.00%, p=3.8×10−3. TARDBP: 2.00% vs 0.45%, p=0.035). The overall frequencies of FUS and OPTN variants were similar (FUS: 0.30% vs 0.45%, p=0.61. OPTN: 0.20% vs 0.23%, p=1). ANG variants were identified only among Italian patients but the frequency difference was not significant (0.30% vs 0.00%, p=0.56).

Table 3.

The frequencies of ALS variants are population specific

| Gene | Variant | % Italian (n=1003) | % Irish (n=444) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANG | c.232A>G(p.K54E) | 0.1 | 0 | 0.56* |

| c.338G>A(p.W89X) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.433C>T(p.R121C) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| C9orf72 | Repeat Expansion | 4.39 | 8.78 | 3.95×10−4* |

| FUS | c.1542G>C(p.R514S) | 0.1 | 0 | 0.18†, 0.61* |

| c.1562G>T(p.R521L) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.1574C>T(p.P525L) | 0.1 | 0.45 | ||

| OPTN | c.1192C>G(p.GLn398Glu) | 0 | 0.23 | 1†, 1* |

| c.1499T>C(p.L500P) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.1703T>C(p.L568S) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| SOD1 | c.34G>T(p.D11Y) | 0.3 | 0 | 3.7×10−3* |

| c.59A>G(p.N19S) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.63C>G(p.F20L) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.115C>G(p.L38V) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.142G>T(p.V47F) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.203T>C(p.L67P) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.256G>A(p.G85S) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.271G>A(p.D90N) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.272A>C(p.D90A) | 0.3 | 0 | ||

| c.281G>A(p.G93D) | 0.3 | 0 | ||

| c.328G>T(p.D109Y) | 0.2 | 0 | ||

| c.400_402delGAA(p.E133del) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.435G>C(p.L144F) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| TARDBP | c.800A>G(p.N267S) | 0.2 | 0 | 0.026†, 0.035* |

| c.859G>A(p.Gly287Ser) | 0 | 0.45 | ||

| c.881G>T(p.G294V) | 0.2 | 0 | ||

| c.909A>C(p.Q303H) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.1009A>G(p.M337V) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.1102G>A(p.G368S) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.1144G>A(p.A382T) | 0.9 | 0 | ||

| c.1147A>G(p.I383V) | 0.1 | 0 | ||

| c.1169A>G(p.N390S) | 0.3 | 0 | ||

| Combined | – | 9.07 | 9.91 | 1.7×10−4†, 0.25* |

Analysed variants include the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion and non-synonymous variants reported as patient specific. Analysis of TARDBP was restricted to exon 6 while analysis of FUS was restricted to exons 14 and 15 and analysis of OPTN was restricted to exons 5, 9, 12 and 14.3.

*Comparison of combined variant frequencies using a Fisher exact test.

†Comparison of independent variant frequencies using a c-α test.

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Single variant association testing

Case–control association tests were performed under additive, dominant and recessive disease models and under various sample and variant inclusion criteria; however, no significant associations with disease risk were observed.

Discussion

We have screened a population-based cohort of 444 Irish ALS patients and 311 age-matched and geographically matched controls for variants within the coding exons of 33 previously reported ALS genes. This represents the most extensive survey of known ALS loci to date and is the first to employ a multiplexed targeted next-generation sequencing strategy to efficiently analyse multiple ALS loci simultaneously. The resulting dataset exhibited high sensitivity in terms of predicted power to identify rare patient variants and high accuracy in terms of genotype assignment.

We found that up to 17.1% of Irish ALS cases (38.0% of fALS, 14.5% of sALS) may carry high-penetrance disease variants within the investigated genes. However, only 10 of the 33 genes analysed represent well-established Mendelian disease genes, and it is anticipated that many of the possible disease variants identified will not be ALS related. Additionally, it should be noted that variants of ALS2 and SPG11 were observed solely in heterozygous configurations, but that these genes have previously been associated with ALS only under recessive disease models.30 31 It is also worth noting that as reported in previous studies,32 no disease variants could be identified within the coding sequence of the C9orf72 gene.

A total of 9.7% of the patients (30% of fALS, 7.1% of sALS) were found to carry previously reported ALS variants, with 8.78% carrying the C9orf72 repeat expansion, 0.45% carrying the FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) substitution and 0.45% carrying the TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) substitution. The phenotype of FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) carriers was consistent with that reported previously,27 with both patients exhibiting an exceptionally young age of onset and rapid disease progression. Conversely, we observed that carriers of the TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) variant exhibited a disease of comparatively late onset and slow progression. Review of TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) carriers reported across this study and previous publications24–26 revealed that disease onset ranged from 52 to 70 years of age while disease duration ranged from 49 to ≥93 months.

Despite prior evidence to support models of high disease penetrance, 62% of C9orf72 expansion carriers and all FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) and TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) carriers were classified as sporadic. Modelling of the effects of penetrance and family size on the rate of familial disease has previously shown that inheritance of high-penetrance variants can occur in the absence of a detectable family history.33 Conversely, the presence of a family history does not necessarily infer the presence of a common disease aetiology9 and it is not always the case that disease variants are inherited. For example, the FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) substitution has been reported to occur as a de novo event in multiple cases.27 Taken together, our results therefore support the contention that the distinction between familial and sporadic disease is of limited utility from both clinical and research perspectives.

Substantial differences have been described in the general spectrum of rare and low-frequency genetic variations across populations.15 34 A degree of population differentiation would therefore also be anticipated in the genetics of disease pathogenesis. Formal comparison of our results with those reported by studies of major disease genes in Italy confirmed that this is the case with ALS. We observed significant differences in the nature of genetic susceptibility across the two populations (p=1.7×10−4), finding that only two of the 32 variants identified among either Irish or Italian patients could be identified among both. One of these shared variants was the FUS:c.1574C>T(p.[P525L]) substitution, which is notable as limited population differentiation may have been predicted a priori, given the associated age of mortality and the importance of de novo occurrence. The other was the C9orf72 repeat expansion, which has been shown to occur with high frequency among various European populations.3 5 35 However, we observed that the expanded allele occurred with a significantly higher frequency in the Irish population than the Italian (Irish=8.78% , Italian=4.39%, p=3.95×10−4). Conversely, we observed that variants of SOD1and TARDBP were significantly more common among Italian patients than Irish (SOD1:Irish=0.00%, Italian=2.00%, p=3.8×10−3. TARDBP:Irish=0.45%, Italian=2.00%, p=0.035). The absence of SOD1 variants in the Irish population is particularly striking, as the gene is believed to make significant contributions to disease burden across Scandinavia (9.6%),36 the USA (7.5%),3,7 Germany (12%—familial cases only),38 Italy (2.1%),3 France (56%—familial cases only)39 and Korea (3.9%).7

A recent analysis of ALS patients from the Netherlands revealed that mutations of multiple ALS-associated genes could be identified in 9/57 families (p=1.57×10−7),5 suggesting that oligogenic susceptibility may play an important role in ALS aetiology. In the current study, we searched for excesses in the co-occurrence of rare and low-frequency variations across a wider panel of disease genes. Our findings did not reveal any significant deviations from chance expectation, even when the analysis was restricted to genes analysed in the Dutch study (data not shown). However, we did observe that 1.6% of patients (4.0% of fALS, 1.3% of sALS) carried multiple variants classified as known or potential high-penetrance ALS variants and that this included all identified carriers of one previously reported ALS variant (p<0.01). This variant occurred within the TARDBP gene (TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S])), which is noteworthy as the strongest evidence for oligogenic-based disease in the Dutch analysis also related to a TARDBP variant (c.1055A>G(p.[N352S])). TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) has previously been identified among patients from Italy,24 France26 and the UK25 but has not yet to our knowledge been reported in healthy controls. As studies that have previously reported the variant analysed the TARDBP gene in isolation, it is not known whether carriers identified elsewhere also carry additional disease variants. The potential relevance of oligogenic susceptibility in ALS aetiology means that the exploration of oligogenic models may become increasingly important in disease gene mapping and studies of genotype–phenotype correlations. It also means that known disease genes should be studied together rather than in isolation and that patients testing positive for disease variants at one locus should not be excluded from subsequent analysis of additional disease loci.

No associations were established between any of the identified variants and case–control status. However, power to evaluate the pathogenicity of low-frequency variants was limited and further investigation of patients and matched controls by future studies may reveal disease-relevant effects. We have therefore provided a complete account of the variation identified across both cases and controls (see online supplementary table S2).

Strong correlations have been observed between patient phenotypes and individual disease variants20 27 and it may be the case that other clinical features such as the frequency of cognitive impairment, the burden of disability and drug response also vary across populations. While the clinical phenotype within European populations is broadly similar, our data would suggest that general extrapolation of findings from individually characterised ancestral populations must be undertaken with caution. A deeper understanding of disease heterogeneity across populations will require further analysis of representative patient cohorts, and is likely to be of benefit in cohort stratification for future clinical trials.

In conclusion, we have used targeted high-throughput sequencing to conduct an extensive population-based survey of ALS gene variant frequencies. We found that 17.1% of Irish cases may carry high-penetrance disease variants within the investigated genes, with previously established disease variants accounting for up to 9.7%. We have also found that the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion represents the most common of these variants. Our study was limited by the exclusion of more recently reported disease genes like SQSTM140 and UBQLN241 and by the absence of any functional analyses of putative disease variants. However, we identified significant differences in the frequencies of disease variants between Irish and other European populations, demonstrating that distinct patient populations cannot always be treated as homogenous. Finally, we also uncovered evidence that supports the potential relevance of oligogenic susceptibility in ALS aetiology and suggests that the TARDBP:c.859G>A(p.[G287S]) variant may not cause disease in isolation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KPK: study design. Preparation of genomic sequencing libraries and target enrichment. Alignment of sequence data and related quality control. Variant calling and related quality control. All statistical analyses, drafting of manuscript. RLM: study design. Preparation of genomic sequencing libraries and target enrichment. Alignment of sequence data and related quality control, drafting of manuscript. SB: study design. Investigation of patient family histories. ME: cognitive testing of patients. MH: data management and retrieval from the Irish ALS Register. EMK: next-generation sequencing and related quality control at TrinSeq. PC: next-generation sequencing and related quality control at TrinSeq. DWM: next-generation sequencing and related quality control at TrinSeq. CGD: provision of DNA and clinical details relating to patients from Northern Ireland. DGB: study design and supervision, editing of manuscript. OH: principal investigator, study design and supervision, patient collection and phenotyping, director of the ALS Register, drafting and editing of manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Health Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement n° 259867, the Irish Health Research Board and the charities Trinity Foundation and Research Motor Neurone. Next-generation sequencing was performed in TrinSeq (http://www.medicine.tcd.ie/sequencing), a core facility funded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) under Grant No. [SFI/07/RFP/GEN/F327/EC07] with support from the Trinity Centre for High Performance Computing.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Research and Ethics committee in Beaumont Hospital, Dublin.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Johnston CA, Stanton BR, Turner MR, Gray R, Blunt AH, Butt D, Ampong MA, Shaw CE, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in an urban setting: a population based study of inner city London. J Neurol 2006;253:1642–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abel O, Powell JF, Andersen PM, Al-Chalabi A. ALSoD: a user-friendly online bioinformatics tool for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Hum Mutat 2012;33:1345–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chio A, Calvo A, Mazzini L, Cantello R, Mora G, Moglia C, Corrado L, D'Alfonso S, Majounie E, Renton A, Pisano F, Ossola I, Brunetti M, Traynor BJ, Restagno G. Extensive genetics of ALS: a population-based study in Italy. Neurology 2012;79:1983–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lattante S, Conte A, Zollino M, Luigetti M, Del Grande A, Marangi G, Romano A, Marcaccio A, Meleo E, Bisogni G, Rossini PM, Sabatelli M. Contribution of major amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genes to the etiology of sporadic disease. Neurology 2012;79:66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Blitterswijk M, van Es MA, Hennekam EAM, Dooijes D, van Rheenen W, Medic J, Bourque PR, Schelhaas HJ, van der Kooi AJ, de Visser M, de Bakker PIW, Veldink JH, van den Berg LH. Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:3776–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Es MA, Dahlberg C, Birve A, Veldink JH, van den Berg LH, Andersen PM. Large-scale SOD1 mutation screening provides evidence for genetic heterogeneity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:562–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon M-J, Baek W, Ki C-S, Kim HY, Koh S-H, Kim J-W, Kim SH. Screening of the SOD1, FUS, TARDBP, ANG, and OPTN mutations in Korean patients with familial and sporadic ALS. Neurobiol Aging 2012;33:1017.e17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Toole O, Traynor BJ, Brennan P, Sheehan C, Frost E, Corr B, Hardiman O. Epidemiology and clinical features of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Ireland between 1995 and 2004. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:30–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne S, Bede P, Elamin M, Kenna K, Lynch C, McLaughlin R, Hardiman O. Proposed criteria for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011;12:157–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig DW, Pearson JV, Szelinger S, Sekar A, Redman M, Corneveaux JJ, Pawlowski TL, Laub T, Nunn G, Stephan DA, Homer N, Huentelman MJ. Identification of genetic variants using bar-coded multiplexed sequencing. Nat Methods 2008;5:887–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010;26:589–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009;25:2078–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20:1297–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics 2010;26:2069–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 2012;491:56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flicek P, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Brent S, Carvalho-Silva D, Clapham P, Coates G, Fairley S, Fitzgerald S, Gil L, Gordon L, Hendrix M, Hourlier T, Johnson N, Kahari AK, Keefe D, Keenan S, Kinsella R, Komorowska M, Koscielny G, Kulesha E, Larsson P, Longden I, McLaren W, Muffato M, Overduin B, Pignatelli M, Pritchard B, Riat HS, Ritchie GRS, Ruffier M, Schuster M, Sobral D, Tang YA, Taylor K, Trevanion S, Vandrovcova J, White S, Wilson M, Wilder SP, Aken BL, Birney E, Cunningham F, Dunham I, Durbin R, Fernandez-Suarez XM, Harrow J, Herrero J, Hubbard TJP, Parker A, Proctor G, Spudich G, Vogel J, Yates A, Zadissa A, Searle SMJ. Ensembl 2012. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40(Database issue):D84–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenna KP, McLaughlin RL, Hardiman O, Bradley DG. Using reference databases of genetic variation to evaluate the potential pathogenicity of candidate disease variants. Hum Mutat 2013;34:836–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neale BM, Rivas MA, Voight BF, Altshuler D, Devlin B, Orho-Melander M, Kathiresan S, Purcell SM, Roeder K, Daly MJ. Testing for an unusual distribution of rare variants. PLoS Genet 2011;7:e1001322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PIW, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byrne S, Elamin M, Bede P, Shatunov A, Walsh C, Corr B, Heverin M, Jordan N, Kenna K, Lynch C, McLaughlin RL, Iyer PM, O'Brien C, Phukan J, Wynne B, Bokde AL, Bradley DG, Pender N, Al-Chalabi A, Hardiman O. Cognitive and clinical characteristics of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis carrying a C9orf72 repeat expansion: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:232–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Ber I, Camuzat A, Berger E, Hannequin D, Laquerriere A, Golfier V, Seilhean D, Viennet G, Couratier P, Verpillat P, Heath S, Camu W, Martinaud O, Lacomblez L, Vercelletto M, Salachas F, Sellal F, Didic M, Thomas-Anterion C, Puel M, Michel B-F, Besse C, Duyckaerts C, Meininger V, Campion D, Dubois B, Brice A. Chromosome 9p-linked families with frontotemporal dementia associated with motor neuron disease. Neurology 2009;72:1669–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenny EM, Cormican P, Gilks WP, Gates AS, O'Dushlaine CT, Pinto C, Corvin AP, Gill M, Morris DW. Multiplex target enrichment using DNA indexing for ultra-high throughput SNP detection. DNA Res 2011;18:31–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cronin S, Berger S, Ding J, Schymick JC, Washecka N, Hernandez DG, Greenway MJ, Bradley DG, Traynor BJ, Hardiman O. A genome-wide association study of sporadic ALS in a homogenous Irish population. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17:768–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrado L, Ratti A, Gellera C, Buratti E, Castellotti B, Carlomagno Y, Ticozzi N, Mazzini L, Testa L, Taroni F, Baralle FE, Silani V, D'Alfonso S. High frequency of TARDBP gene mutations in Italian patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mutat 2009;30:688–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirby J, Goodall EF, Smith W, Highley JR, Masanzu R, Hartley JA, Hibberd R, Hollinger HC, Wharton SB, Morrison KE, Ince PG, McDermott CJ, Shaw PJ. Broad clinical phenotypes associated with TAR-DNA binding protein (TARDBP) mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurogenetics 2010;11:217–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard J-P, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, Pradat P-F, Camu W, Meininger V, Dupre N, Rouleau GA. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet 2008;40:572–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conte A, Lattante S, Zollino M, Marangi G, Luigetti M, Del Grande A, Servidei S, Trombetta F, Sabatelli M. P525L FUS mutation is consistently associated with a severe form of juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuromuscul Disord 2012;22:73–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 2009;4:1073–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 2010;7:248–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orlacchio A, Babalini C, Borreca A, Patrono C, Massa R, Basaran S, Munhoz RP, Rogaeva EA, St George-Hyslop PH, Bernardi G, Kawarai T. SPATACSIN mutations cause autosomal recessive juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2010;133(Pt 2):591–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Hentati A, Deng HX, Dabbagh O, Sasaki T, Hirano M, Hung WY, Ouahchi K, Yan J, Azim AC, Cole N, Gascon G, Yagmour A, Ben-Hamida M, Pericak-Vance M, Hentati F, Siddique T. The gene encoding alsin, a protein with three guanine-nucleotide exchange factor domains, is mutated in a form of recessive amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet 2001;29:160–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harms MB, Cady J, Zaidman C, Cooper P, Bali T, Allred P, Cruchaga C, Baughn M, Libby RT, Pestronk A, Goate A, Ravits J, Baloh RH. Lack of C9ORF72 coding mutations supports a gain of function for repeat expansions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging 2013. Published Online First: Epub Date.10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Chalabi A, Lewis CM. Modelling the effects of penetrance and family size on rates of sporadic and familial disease. Hum Hered 2011;71:281–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tennessen JA, Bigham AW, O'Connor TD, Fu W, Kenny EE, Gravel S, McGee S, Do R, Liu X, Jun G, Kang HM, Jordan D, Leal SM, Gabriel S, Rieder MJ, Abecasis G, Altshuler D, Nickerson DA, Boerwinkle E, Sunyaev S, Bustamante CD, Bamshad MJ, Akey JM. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science 2012;337:64–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majounie E, Renton AE, Mok K, Dopper EGP, Waite A, Rollinson S, Chio A, Restagno G, Nicolaou N, Simon-Sanchez J, van Swieten JC, Abramzon Y, Johnson JO, Sendtner M, Pamphlett R, Orrell RW, Mead S, Sidle KC, Houlden H, Rohrer JD, Morrison KE, Pall H, Talbot K, Ansorge O, Hernandez DG, Arepalli S, Sabatelli M, Mora G, Corbo M, Giannini F, Calvo A, Englund E, Borghero G, Floris GL, Remes AM, Laaksovirta H, McCluskey L, Trojanowski JQ, Van Deerlin VM, Schellenberg GD, Nalls MA, Drory VE, Lu C-S, Yeh T-H, Ishiura H, Takahashi Y, Tsuji S, Le Ber I, Brice A, Drepper C, Williams N, Kirby J, Shaw P, Hardy J, Tienari PJ, Heutink P, Morris HR, Pickering-Brown S, Traynor BJ. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:323–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen PM, Nilsson P, Keranen ML, Forsgren L, Hagglund J, Karlsborg M, Ronnevi LO, Gredal O, Marklund SL. Phenotypic heterogeneity in motor neuron disease patients with CuZn-superoxide dismutase mutations in Scandinavia. Brain 1997;120(Pt 10):1723–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown JA, Min J, Staropoli JF, Collin E, Bi S, Feng X, Barone R, Cao Y, O'Malley L, Xin W, Mullen TE, Sims KB. SOD1, ANG, TARDBP and FUS mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a United States clinical testing lab experience. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012;13:217–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niemann S, Joos H, Meyer T, Vielhaber S, Reuner U, Gleichmann M, Dengler R, Muller U. Familial ALS in Germany: origin of the R115G SOD1 mutation by a founder effect. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1186–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millecamps S, Salachas F, Cazeneuve C, Gordon P, Bricka B, Camuzat A, Guillot-Noel L, Russaouen O, Bruneteau G, Pradat P-F, Le Forestier N, Vandenberghe N, Danel-Brunaud V, Guy N, Thauvin-Robinet C, Lacomblez L, Couratier P, Hannequin D, Seilhean D, Le Ber I, Corcia P, Camu W, Brice A, Rouleau G, LeGuern E, Meininger V. SOD1, ANG, VAPB, TARDBP, and FUS mutations in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: genotype-phenotype correlations. J Med Genet 2010;47:554–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fecto F, Yan J, Vemula SP, Liu E, Yang Y, Chen W, Zheng JG, Shi Y, Siddique N, Arrat H, Donkervoort S, Ajroud-Driss S, Sufit RL, Heller SL, Deng H-X, Siddique T. SQSTM1 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2011;68:1440–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng H-X, Chen W, Hong S-T, Boycott KM, Gorrie GH, Siddique N, Yang Y, Fecto F, Shi Y, Zhai H, Jiang H, Hirano M, Rampersaud E, Jansen GH, Donkervoort S, Bigio EH, Brooks BR, Ajroud K, Sufit RL, Haines JL, Mugnaini E, Pericak-Vance MA, Siddique T. Mutations in UBQLN2 cause dominant X-linked juvenile and adult-onset ALS and ALS/dementia. Nature 2011;477:211–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.