Abstract

Background

Naltrexone is approved for the treatment of alcohol dependence when used in conjunction with a psychosocial intervention. This study was undertaken to examine the impact of 3 types of psychosocial treatment combined with either naltrexone or placebo treatment on alcohol dependency over 24 weeks of treatment: (1) Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) + medication clinic, (2) BRENDA (an intervention promoting pharmacotherapy) + medication clinic, and (3) a medication clinic model with limited therapeutic content.

Methods

Two hundred and forty alcohol-dependent subjects were enrolled in a 24-week double- blind placebo-controlled study of naltrexone (100 mg/d). Subjects were also randomly assigned to 1 of 3 psychosocial interventions. All patients were assessed for alcohol use, medication adherence, and adverse events at regularly scheduled research visits.

Results

There was a modest main treatment effect for the psychosocial condition favoring those subjects randomized to CBT. Intent-to-treat analyses suggested that there was no overall efficacy of naltrexone and no medication by psychosocial intervention interaction. There was a relatively low level of medication adherence (50% adhered) across conditions, and this was associated with poor outcome.

Conclusions

Results from this 24-week treatment study demonstrate the importance of the psychosocial component in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Moreover, results demonstrate a substantial association between medication adherence and treatment outcomes. The findings suggest that further research is needed to determine the appropriate use of pharmacotherapy in maximizing treatment response.

Keywords: Alcohol Dependence, Treatment, Naltrexone, Psychotherapy

There continues to be a need to develop better treatment models for alcohol dependence as evidenced by the relatively low rates of access to treatments found in epidemiological studies (Grant et al., 2004). The Institute of Medicine has suggested that intervening for alcohol dependence with pharmacotherapy in the primary care setting or other nonspecialty care settings may be an effective way to address the gap between treatment need and lack of access (Institute of Medicine, 1996, 2005). Currently, there are 3 FDA-approved pharmacotherapies available for the treatment of alcohol dependence—disulfiram, naltrexone (both oral and depot formulations), and acamprosate. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, has been used successfully in the treatment of alcohol dependence (e.g., O’Malley et al., 1992 and Volpicelli et al., 1992) and is safe and well tolerated (Croop et al., 1997; O’Malley et al., 1992; Volpicelli et al., 1992). The majority of studies continue to show a greater efficacy of naltrexone over placebo either in the main (Anton et al., 1999; Jaffe et al., 1996; Monterosso et al., 2001; Morris et al., 2001; Volpicelli et al., 1997b) or secondary analysis (Chick et al., 2000; Heinala et al., 2001; Monti et al., 2001; Oslin et al., 1997). Although this evidence for the effectiveness of naltrexone is compelling, a few studies have failed to show the efficacy of naltrexone (Kranzler et al., 2000; Krystal et al., 2001).

So far, all clinical intervention research studies except 2 (Latt et al., 2002; O’Malley et al., 2003) have delivered naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence only in the context of a formal psychosocial intervention (CBT, MET, MM, etc). However, many of these interventions require a substantial commitment to specialty training and require multiple visits by the patient. Thus, the effectiveness of naltrexone in the absence of formal psychotherapy has not been well investigated. In addition, there are several types of psychosocial interventions that could be effectively combined with pharmacotherapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be an effective psychosocial treatment for alcohol dependence (Kadden et al., 1995) and has been theorized to be beneficial for enhancing naltrexone effectiveness (Anton et al., 1999; Jaffe et al., 1996; O’Malley et al., 1992). A CBT-based intervention was used for all subjects in a study that showed naltrexone to be superior to placebo (Anton et al., 1999), and group CBT was shown to enhance the effectiveness of naltrexone over group supportive therapy in a study by Heinala et al. (2001). Recently, a 12-week study demonstrated that the combination of naltrexone and CBT was more effective than placebo or motivational enhancement therapy (MET) with or without naltrexone (Anton et al., 2005). It is theorized that this effect may relate to the need for addressing psychosocial issues not specifically dealt with in MET. CBT has specific modules on family conflict, social skills training to deal with high-risk situations, and coping with craving, which are not generally part of MET therapy. However, a larger NIAAA-supported COMBINE study failed to demonstrate an advantage of receiving CBT treatment while taking naltrexone compared to taking naltrexone with Medical Management (MM), a less-intensive therapy (Anton et al., 2006). Less-intensive motivationally based interventions such as MM have been theorized to provide a strong platform in which to deliver pharmacotherapy (Pettinati et al., 2004). The BRENDA model (Volpicelli et al., 1997a) was also designed specifically to be used in combination with pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence and includes motivational enhancement counseling with a goal of promoting reductions in alcohol use while promoting adherence to treatment. BRENDA served as the psychosocial intervention in a trial that found naltrexone to be superior to placebo (Monterosso et al., 2001), suggesting that it is a viable intervention. Delivered by nurses or other allied health professionals, BRENDA or MM could be used in multiple clinical settings including specialty care or primary care. The BRENDA and MM models are based on MET but includes specific discussions around pharmacotherapy. BRENDA does not include the structure found in CBT and, in particular, does not have modules for family involvement, methods for social skills training, or coping with craving.

The aims of this project were to test the main effects of naltrexone/placebo and the main effects of specific psychosocial interventions, including a medication clinic model alone, over the course of 24 weeks of treatment. The medication clinic model was included to mimic clinical practice typically seen in nonspecialty settings such as primary care. This model of care is common in the treatment of depression. The CBT condition was included as the “gold standard” treatment with proven efficacy in the treatment for addiction. We hypothesized moderate-to-large treatment effects favoring naltrexone as well as between the 3 psychosocial intervention groups, with CBT and BRENDA hypothesized to be better than the medication clinic model. The sample size (240 subjects) was sufficient to demonstrate at least moderate differences in the main effects assuming 80% or better treatment adherence over the 24 weeks. The original hypothesis also included a testing of the interaction between psychosocial intervention and medication; however, the sample size would only be sufficient for very large interaction effects. The focus on 24 weeks of treatment was based on reports of several post-treatment follow-up results (Anton et al., 1999; Monti et al., 2001; O’Malley et al., 1996), which suggested that discontinuing naltrexone after 3 months leads to a gradual return to heavy alcohol use, and that longer durations of naltrexone administration might be useful.

METHODS

Two hundred and forty outpatients were enrolled in a 24-week, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of naltrexone 100 mg/d for alcohol dependence. The trial was double-blind with respect to medication. Study participants were recruited through advertisements in the local media. Eligible subjects had to be at least 18 years of age, meet DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence as assessed by the SCID diagnostic interview, and obtain a minimum of 3 consecutive days of abstinence prior to the start of the study medication. Subjects were not included if they had a current DSM-IV diagnosis of any psychoactive substance dependence (SCID diagnosis) other than alcohol or had evidence of opioid abuse in the past 30 days, as assessed by both self-report and/or urine drug screen at admission to treatment. Subjects could not be taking psychotropic medications or have evidence of current severe psychiatric symptoms based on a SCID diagnosis of psychosis, mania, or PTSD. Subjects also could not have severe medical illnesses such as active hepatitis and could not have significant hepatocellular injury, as evidenced by elevated total bilirubin levels. Female patients who were pregnant, nursing, or not using a reliable method of contraception were also excluded. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania, and all subjects provided written informed consent prior to study participation.

Study Design

Subjects were randomized to 1 of 6 conditions: (1) naltrexone given in the context of a medication clinic visit (doctor Only), (2) placebo plus medication clinic visit (Doctor only), (3) naltrexone plus medication clinic visit and BRENDA (Volpicelli et al., 1997a), (4) placebo plus medication clinic visit and BRENDA, (5) naltrexone plus medication clinic visit and CBT, and (6) placebo plus medication clinic visit and CBT. Subjects on active medication received 100 mg of naltrexone daily if tolerated. If not, patients were maintained on 50 mg/d. Subjects on placebo received identical appearing pills according to the same regimen. The decision to use 100-mg doses was based on the following observations. A dosing study for naltrexone has never been conducted, but there is evidence of significant intraindividual differences in metabolism to suggest that some patients require higher doses to achieve detectable serum levels (McCaul et al., 2000). It has also been observed that a 50-mg dose provides highly variable blockade of the kappa and delta opioid receptors and this may relate to efficacy (Weerts et al., 2007).

Psychosocial Treatments

Medication clinic visits consisted of a total of 9, 5- to 10-minute sessions with a research physician over 24 weeks. The sessions were initially weekly, spacing out to twice per month then monthly over the last 3 months of the trial. Each time the research physician saw the subject, she/he informally asked about alcohol use and any medication side effects or recent illnesses. She/he also dispensed medication and reminded the subject to call prior to taking any other medications to prevent drug interactions. Subjects were expected to return their study medication blister cards at each visit for pill counts. In both the BRENDA and CBT conditions, subjects could receive up to 18 sessions starting weekly during the first 12-weeks of treatment, and then every other week thereafter. Staff in the BRENDA and CBT conditions were supervised at least monthly to maintain fidelity of the treatments. The supervisors for each condition were consistent throughout the trial. Based on supervision and a 10% review and rating of random audiotapes, there was no evidence of therapeutic drift over the course of the trial. The ratings were based on the presence of key elements of each therapy model and were applied as a simple checklist.

BRENDA was conducted by a nurse practitioner with sessions lasting 20 to 30 minutes (Volpicelli et al., 1997a). BRENDA, a manualized psychosocial intervention that includes motivational enhancement counseling, is an acronym for the following 6-stage framework that comprises the treatment: Bio-psychosocial evaluation, Report to patient on assessments including linking drinking to health status and social problems, Empathetic understanding of the patient’s situation, Needs that must be addressed, Direct advice to patient on how to meet those needs, and Assess reaction/behaviors of patient to advice and adjust as necessary for best care. Each session focused on progress made toward the goal of reducing alcohol consumption. Each session also focused on adherence to treatment (attendance and pharmacotherapy). Advice centered on problem-solving skills and promoting positive self-change. While abstinence is the stated goal for each patient, reductions in drinking were encouraged while working toward this goal. Supervision by JRV was available monthly or as needed.

The CBT techniques were conducted by a CBT-trained therapist (clinical psychologist or social worker) with sessions lasting 50 to 60 minutes. CBT uses a functional analysis to identify and process drinking-urge triggers and life problems using a problem-solving/skills training format along with practice assignments (Kadden et al., 1995). Typical skill modules included in CBT treatment are: coping with craving and handling a lapse, drink refusal skill, general problem solving, all-purpose coping, and Mood Management. Supervision from PG was available at least monthly or as needed.

Assessment Instruments

Outcome and adherence measures were obtained by trained technicians who were blinded to medication assignment and were not directly involved in the treatment of subjects. Medication adherence was measured using a method of well-marked blister cards, pill counts, and patient interviews (Pettinati et al., 2000), while clinic visit attendance was tracked by chart reviews. Adverse events were monitored weekly by the research physician’s probing for side effects commonly associated with naltrexone. All adverse events/side effects were considered during the trial unless they were reported prior to randomization. In the case of pre-existing symptoms, the symptom was only considered an adverse effect if it represented a worsening of that symptom.

Standard research assessments measured the amount of drinking, severity of alcohol problems, and psychosocial functioning. None of the research assessments were made available to clinical staff. The instruments included the Time Line Follow-Back (TLFB) method of assessing alcohol consumption (Sobell and Sobell, 1992; Sobell et al., 1988) and the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC) (Miller et al., 1995). The TLFB is a semi-structured interview that uses a calendar format to record the quantity and frequency of drinking per day during a stated period of time. In this instance, drinking reports were recorded for the 90 days preceding enrollment, as well as during the treatment period following randomization. Quantity of alcohol was recorded in standard drinks (e.g., a 12-oz beer, a 5-oz glass of wine, or a 1½ oz shot of liquor). Heavy drinking (relapse) was defined as 5 or more drinks in a single day for men, and 4 or more for women. The heavy-drinking criteria were based on other pharmacotherapy trials, although lower levels of consumption could be considered significant (Anton, 1996; Kranzler et al., 2001; Volpicelli et al., 1992). The DrInC is a 50-item self-report questionnaire that measures adverse consequences of alcohol abuse in 5 areas: physical, social, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and impulse control (Miller et al., 1995). The DrInC was normed in a sample of individuals seeking treatment for alcohol problems in either outpatient or inpatient settings; decile rankings are provided for males and females in relation to the comparison group.

Statistical Analysis

For demographic and pretreatment drinking characteristics, means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. General linear modeling and logistic regression, respectively, were used to assess group differences. These analyses were similarly used to analyze quantitative and categorical variables measured during treatment, including research participation variables, adverse effects, and drinking characteristics. The principal outcome analyses used generalized estimating equations to investigate the joint effects of medication group and psychosocial intervention group on drinking outcomes over the 24-week treatment phase of the study (Diggle et al., 2002). Outcomes were considered in each of the 6, 4-week blocks of time. These analyses, unlike survival analyses, do not restrict the analytic focus to the first day of heavy drinking when there can be more than 1 day of heavy drinking over time. Four types of outcomes were considered including the number of days per time block of abstinence, the number of days per time block of heavy drinking, and binary categories of any drinking in the time block or any heavy drinking. Because of skewed distributions for the number of days of abstinence or heavy drinking, log transformations were applied. The models included terms from the main effects of medication and psychotherapy groups, and their interaction, and terms for linear and quadratic time trends, together with 2- and 3-way interactions between medication group, psychotherapy group, and the time trends. These models accommodate the possibility of different quadratic time trends for each of the 6 medication by psychotherapy groups. The quadratic trends were included in the models to allow for the possibility that responses might decrease (or increase) early in treatment and then change less quickly over the rest of the treatment. To present results comparable with results commonly reported in other studies, time to first day of heavy drinking was also investigated using survival analyses.

In an exploratory analysis, log-linear models were used to assess patterns of nonadherence over time. In this context, medication nonadherence was defined as the first day in the trial that the patient stopped taking medication for 7 days or more, including the point of early dropout from the study. Subjects, who both relapsed and were medication nonadherent, were further classified regarding the timing of these 2 events. Subjects who reported relapsing and becoming medication nonadherent within a 5-day window were coded as having both events occur at the same time; otherwise the 2 events were coded separately.

The longitudinal analyses using GEE models described above use all available data, and ignore any missing data, and are valid only when missingness is independent of all covariates and responses. We therefore investigated separately the effects of adherence to clinic visits and adherence to medication, as well as missing data on outcomes. A pattern mixture strategy (Park and Lee, 1999) was used to assess the sensitivity of the results to the assumption that missing data were ignorable, by classifying each subject into one of the main missing data patterns present in the data, e.g., a binary variable indicating completer versus noncompleter, or an ordinal variable indicating time to dropout. Pattern mixture models test for an association between treatment effect and missing data by testing for interactions between these indicator variables and the main design variables (medication group, psychotherapy group, time). Significant interactions provide evidence of variation in treatment effect across different types of missing data pattern, and hence suggest that analyses ignoring missing data are invalid. Valid estimates are obtained by averaging over-estimated effects over the different “missingness” patterns in the pattern mixture model (Hedeker and Gibbons, 1997). For investigating the effects of adherence on outcome with protection against unmeasured confounding by randomization, we used a longitudinal random effects logistic model developed by Small et al. (2005), which represents an extension of the instrumental variable regression method by Nagelkerke et al. (2000). The goal of these analyses was to obtain an estimate of the effect of treatment relative to control in a population where participants adhered to their assigned treatment. Neither the usual intent-to-treat analysis, nor an analysis based on the “as treated” status of participants, would yield a valid estimate of the effect, unless adherent participants were comparable to nonadherent participants on covariates and responses. The instrumental variable (IV) approach of Nagelkerke et al. (2000) replaces the assumption that adherent participants are comparable to nonadherent participants by a requirement that randomization has no direct effect on outcome, and that its only effect on outcome is the indirect effect via treatment received. Thus, randomization serves as an “instrumental variable”. The contribution was to extend the IV approach to longitudinal trials (Small et al., 2005). Their model yields estimates of the effect of assignment to treatment compared with assignment to control at a given time point, among those participants who would adhere to treatment if assigned to it. Small et al. (2005) chose a random effect approach, and the effect is regarded as conditional on the participant’s random effect.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

For the overall sample, the average age of the subjects was 41 (SD = 9.4) with the majority being male (72.9%) and Caucasian (72.9%). The average years of education was 13.9 (2.7), and 85% were employed. There were no significant differences by treatment assignment on any baseline variable except race (χ2 = 6.32, df = 2, p < 0.05; Table 1). Clinical characteristics prior to treatment suggest that subjects drank an average of 71.6 (27.4) percent of days during the 90 days preceding enrollment, and drank heavily on an average of 64.3 (29.8) percent of these days. Subjects drank an average of 8.7 (6.6) drinks per day during this period. With regard to problem drinking, the average DrInC Score was 28.4 (9.1). The average score for males was 28.6 (9.4) and for females was 27.9 (8.3), which was not significantly different from each other. These average scores fell into the bottom 30 and 40% relative to the normative sample of males and females, respectively. As the normative sample included individuals treated in inpatient settings, this represents a significant degree of alcohol-related problems in the outpatient sample of this study. There were no significant differences between treatment assignments on pretreatment drinking characteristics (Table 1). For each of the outcome measures, baseline covariates were used to adjust for differences at baseline. The following 4 variables were used as covariates in analyses of all outcome variables except for abstinence: percent days heavy-drinking pretreatment, age, race, and gender. Age, race, and gender were included based on the literature suggesting possible effects of each of these on naltrexone response or treatment response in general, even though the groups were not imbalanced on any of these variables. Percent days drinking prior to treatment was substituted as a covariate for percent days heavy drinking prior to treatment in the analysis of abstinence.

Table 1.

Pretreatmenta Drinking and Demographic Characteristics of Sample

| Naltrexone/CBT (n = 40) | Placebo/CBT (n = 40) | Naltrexone/BRENDA (n = 39) | Placebo/BRENDA (n = 40) | Naltrexone/Doctor only (n = 41) | Placebo/Doctor only (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [M(SD)] | 44.6 (10.8) | 44.3 (12.5) | 43.5 (9.5) | 44.3 (10.2) | 41.7 (10.7) | 43.9 (11.1) |

| Male (%) | 72.5 | 72.5 | 74.4 | 72.5 | 73.2 | 72.5 |

| Caucasian (%) | 57.5 | 70.0 | 76.3 | 87.5 | 78.0 | 70.0 |

| Married (%) | 20.0 | 30.0 | 41.0 | 35.9 | 31.7 | 38.5 |

| Education years [M(SD)] | 14.0 (3.21) | 13.6 (1.9) | 14.1 (2.4) | 14.0 (2.82) | 13.6 (2.4) | 14.0 (3.3) |

| Employed (%) | 80.0 | 87.5 | 84.6 | 87.5 | 85.4 | 85.0 |

| Clinical paramaters | ||||||

| DrInC Score (range 0 to 60) | 29.0 (9.8) | 28.0 (10.6) | 28.6 (8.8) | 29.3 (8.7) | 27.8 (8.2) | 27.6 (9.2) |

| ASI Alcohol Score | 0.70 (0.20) | 0.73 (0.18) | 0.69 (0.16) | 0.70 (0.15) | 0.68 (0.19) | 0.68 (0.20) |

| Days drinking (%) | 72.5 (27.4) | 74.3 (27.6) | 65.7 (29.0) | 70.9 (28.5) | 76.3 (22.1) | 70.0 (30.0) |

| Days of heavy drinking (%) | 65.6 (30.0) | 65.1 (30.4) | 61.9 (29.1) | 61.7 (31.0) | 70.8 (26.7) | 60.5 (32.2) |

| Drinks per day | 9.4 (9.1) | 9.1 (6.6) | 7.2 (6.0) | 8.0 (5.1) | 10.1 (6.5) | 8.0 (5.6) |

| DrInC Score (range 0 to 60) | 29.0 (9.8) | 28.0 (10.6) | 28.6 (8.8) | 29.3 (8.7) | 27.8 (8.2) | 27.6 (9.2) |

There were no significant main effects at the p < 0.1 level between naltrexone and placebo, between psychosocial intervention groups, or between medication assignment and psychosocial intervention assignment with the exception of an interaction between race and psychosocial intervention group.

Ninety days preceding enrollment.

Eight subjects failed to participate after randomization and were excluded from analyses of variables assessed during treatment. The subjects were randomized to the following groups: Doctor only/naltrexone (n = 1), Doctor only/placebo (n = 1), BRENDA/naltrexone (n = 3), BRENDA/placebo (n = 1), and CBT/naltrexone (n = 2). There was no medication [Wald = 1.88, df = 1, OR = 0.32 (95% CI: 0.06 to 1.63), p = 0.171] or psychosocial intervention effect [Wald = 0.00, df = 1, OR = 0.99 (95% CI: 0.42 to 2.35), p = 0.982] on not participating in at least 1 follow-up assessment.

Research Participation

As shown in Table 2, 77% of the subjects provided complete data on drinking during the 24-week trial (>160 days of info). There were no medication or psychosocial intervention group assignment effects on research participation.

Table 2.

Trial Completion, Treatment Adherence and Adverse Events of Subjects in Each Treatment Group

| Naltrexone/CBT (n = 40) | Placebo/CBT (n = 40) | Naltrexone/BRENDA (n = 39) | Placebo/BRENDA (n = 40) | Naltrexone/Doctor only (n = 41) | Placebo/Doctor only (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed research visits (%) | 65.0 | 80.0 | 76.9 | 87.5 | 80.5 | 72.5 |

| Drop outs (main reasons) (values represent the number of subjects) | ||||||

| Withdrew consent | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No reason given | 9 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| Known drinking (self-report or family) | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Clinical visits | ||||||

| Clinical sessions (%) | 50.1 (30.1) | 67.1 (28.0) | 65.1 (33.1) | 70.7 (30.1) | 78.8 (30.3) | 73.1 (30.3) |

| Clinical sessions by psychosocial interventiona (%) | 58.6 (29.1) | 67.9 (31.6) | 76.0 (30.3) | |||

| Medication | ||||||

| Taking medication (% days) | 55.7 (39.7) | 64.7 (33.1) | 64.9 (37.3) | 65.3 (36.7) | 63.9 (35.4) | 61.8 (36.4) |

| Took medication on 80% of days during the first 12 weeks (%) | 64.9 | 67.5 | 72.2 | 66.7 | 67.5 | 69.2 |

| Took medication on 80% of days over the entire 24 weeks (%) | 45.0 | 47.5 | 56.4 | 57.5 | 48.8 | 47.5 |

| Adverse effects (most common) (the % reflects the percentage of patients reporting an adverse event anytime during the trial) | ||||||

| Headache (%) | 40.0 | 52.5 | 43.6 | 52.5 | 58.5 | 42.5 |

| Nausea (%) | 50.0 | 40.0 | 43.6 | 45.0 | 43.9 | 25.0 |

| Vomiting (%) | 15.0 | 22.5 | 28.2 | 15.0 | 24.4 | 17.5 |

| Anxiety (%) | 40.0 | 42.5 | 41.0 | 35.0 | 43.9 | 52.5 |

| Insomnia (%)b | 10.0 | 10.0 | 25.6 | 15.0 | 36.6 | 10.0 |

No treatment effects were significant except for an effect of behavioral therapy on treatment attendancea and an effect of medication group on insomniab.

Treatment Adherence

Subjects attended an average of 67.5 (31.3) percent of psychosocial intervention sessions, and took medication an average of 62.7 (36.2) percent of days during the trial. About half (50.4%) took medication on 80% or more of the trial days (considered adherent). There were no significant differences between naltrexone and placebo or between psychosocial interventions on percent of completed research visits, percent days taking medication, or percent who took medication on 80% of days (Table 2). There was a significant difference between psychosocial interventions in the percent of therapy sessions attended. Subjects in the CBT condition attended a significantly lower proportion of clinical visits than did subjects in the Doctor only condition (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ2 = 21.77, df = 2, p < 0.001). All subjects for who took medication took at least 1 dose of 100 mg of naltrexone, 19 subjects (13 of which were on naltrexone) required a dose reduction in medication for more than 5 days. Of these subjects 8 had at least 1 heavy-drinking day and 4 required reductions in medication for most of the trial days all of whom were on naltrexone.

Side Effects

The percentage of subjects by medication–therapy group that reported specific adverse effects is shown in Table 2. Naltrexone-treated subjects (24.2 vs. 11.7%) were significantly more likely to report having had insomnia than subjects receiving placebo (χ2 = 8.103, df = 1, p < 0.01). None of the other side effects differed significantly in occurrence between conditions.

Longitudinal Effects of Treatment

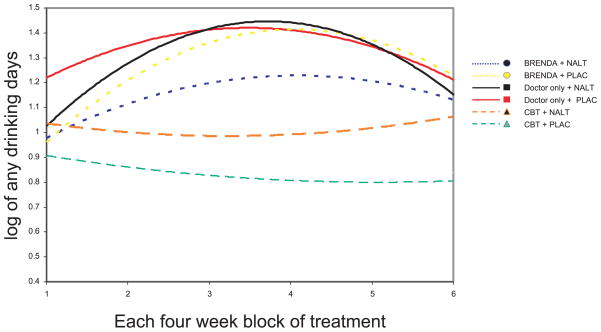

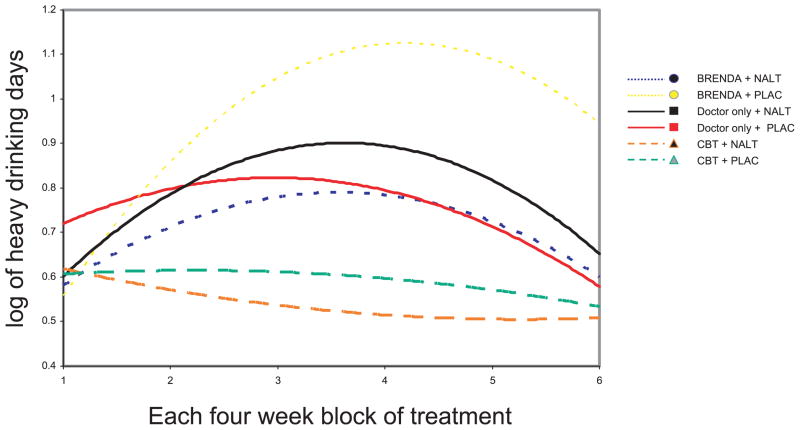

As shown in Fig. 1, the overall trajectory for the number of days of any alcohol use is consistently lower in subjects assigned to CBT, and initially increases and then declines slightly in the other psychosocial intervention groups. Thus, there was a significant quadratic psychosocial intervention by time effect favoring treatment with CBT for the number of days of any drinking (χ2 = 8.29, df = 2, p < 0.01). Similarly, there was a significant quadratic psychosocial intervention by time effect favoring CBT when considering any drinking during the whole of each month (χ2 = 9.38, df=2, p < 0.01). As shown in Fig. 2, the overall trajectory for the number of days of heavy drinking is also consistently lower in subjects assigned to CBT and increases over time in the other psychosocial interventions. Thus, there was a significant linear psychosocial intervention by time effect favoring treatment with CBT for the number of days of any heavy drinking (χ2 = 10.33, df = 2, p < 0.001). Similarly, there was a significant linear psychosocial intervention by time effect favoring CBT when considering any heavy drinking during the whole month (χ2 = 13.15, df = 2, p < 0.001). There were no significant effects of medication by time or medication by psychosocial intervention by time.

Fig. 1.

The number of days of any drinking (log transformed) during each 4-week time block by group. The CBT group demonstrated significantly lower drinking than the other therapy groups (p < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

The number of days of any heavy drinking (log transformed) during each 4-week time block by group. The CBT group demonstrated significantly fewer periods of heavy drinking than the other therapy groups (p < 0.001).

In all of these models, age, prestudy drinking, and to some degree gender are all associated with treatment outcomes. For instance, older age was associated with a greater number of days of abstinence (χ2 = 9.09, df=1, p < 0.01) and fewer heavy-drinking days (χ2 = 19.89, df = 1, p < 0.001). Similarly, greater prestudy drinking was associated with a greater number of days of drinking (χ2 = 15.40, df = 1, p < 0.003) and greater heavy-drinking days (χ2 = 15.41, df = 1, p < 0.001). Women had a greater number of days of drinking (χ2 = 6.29, df = 1, p < 0.05) and greater heavy-drinking days (χ2 = 8.94, df=1, p < 0.01) than men. There was no effect of race on outcome.

Descriptive Outcomes Collapsing Alcohol Consumption Over the Entire Time Period

Overall 20.7% of the subjects were abstinent during their participation. However, there were no significant treatment effects on rates of abstinence (Table 3). The proportion of subjects with any heavy drinking was 62.07%. There were no significant treatment effects for relapse to heavy drinking. Continuous measures of drinking also showed no treatment effects except for a lower percent of days drinking in those receiving CBT.

Table 3.

Descriptive Outcomes of the Medication or Psychosocial Intervention Groups on Drinking Outcomes Collapsed Over the Entire Study Period

| Medication main effects

|

Psychosocial intervention main effects

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naltrexone (n = 120) | Placebo (n = 120) | Medication effects | CBT (C) (n = 80) | BRENDA (B) (n = 79) | Doctor only (D) (n = 81) | B vs. D | C vs. D | |

| Abstinent (%) | 21.1 | 20.3 | OR = 0.93 | 24.4 | 21.3 | 16.5 | OR = 0.82 | OR = 0.62 |

| Any heavy drinking (%) | 60.5 | 63.6 | OR = 0.86 | 59.0 | 61.3 | 65.8 | OR = 0.96 | OR = 0.79 |

| Days drinking (%) | 18.0 (22.4) | 18.4 (23.0) | η2 = 0.00 | 13.7 (20.2) | 19.9 (22.2) | 21.0 (24.9) | η2 = 0.00 | η2 = 0.02 |

| Days heavy drinking (%) | 9.2 (15.5) | 11.2 (17.6) | η2 = 0.01 | 7.6 (14.7) | 11.9 (17.0) | 11.2 (17.5) | η2 = 0.00 | η2 = 0.01 |

| Drinks per day | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.6 (3.2) | η2 = 0.00 | 1.1 (3.3) | 1.6 (2.6) | 1.4 (2.0) | η2 = 0.01 | η2 = 0.00 |

Analyses include age, race, gender and prestudy heavy drinking days as covariates. Effect sizes are partial eta-squared for continuous outcomes (days drinking, days heavy drinking, and drinks per day) and adjusted odds ratios for binary outcomes (abstinent and any heavy drinking). Odds ratios are in direction of worse outcomes. There were no significant differences for the main effects of medication or psychosocial intervention.

Additional Longitudinal Analyses

There was a moderate degree of missing data (23% of the drinking data was not available). A pattern mixture strategy was used to assess the sensitivity of the results to the assumption that missing data were ignorable (Park and Lee, 1999). Due to the limited amount of missing data, a binary variable indicating dropout versus completion was used as a pattern variable. This variable was then included as a main effect and in interaction terms with the medication, psychosocial intervention, and time variables in GEE models similar to those described above. These analyses showed no significant interaction between missing data patterns and medication by psychosocial intervention by time, suggesting that the results may not be confounded by unmeasured factors influencing the missing data.

There were significant associations over time between medication adherence (defined as 80% or greater rates of pill taking) and time to first day of heavy drinking, with greater adherence associated with a longer time to first day of heavy drinking (χ2 = 20.6, df = 1, p < 0.0001). However, there were no “between-medication group” differences in time to first day of heavy drinking, when considering adherent and nonadherent subjects separately.

The investigation of the effects of adherence to psychosocial intervention and, separately, adherence to medication on outcomes based on the longitudinal random effects logistic model with instrumental variables did not change the overall interpretation of the longitudinal results and are not presented for space considerations.

Exploring Patterns of Medication Nonadherence and Heavy Drinking

There was a significant correlation between having a 7-day or greater period of medication nonadherence and heavy drinking (χ2 = 11.25, df = 1, p < 0.001). One hundred and two subjects had both episodes of heavy drinking and were nonadherent to medication for a period of at least 7 days (42.5% of the total sample). For the 102 subjects who relapsed and had periods of nonadherence to medication, the timing of these events was determined. sixty-five (63.7%) reported relapsing before discontinuing medication, 18 (17.6%) reported discontinuing medication before relapsing, and 19 (18.6%) reported relapsing and discontinuing medication within a 5-day interval.

DISCUSSION

There was a consistent finding that patients assigned to CBT had lower rates of heavy drinking and greater rates of abstinence over the 24 weeks of treatment. Although the differences in effect were small and may not represent clinically meaningful effects, the direction of the effect was consistent in all measures and present despite lower rates of treatment adherence. This effect was also only evident when considering time (Figs. 1 and 2) and not when collapsing results over the entire 24 weeks (Table 3). The longitudinal analyses were the principal tests of our hypotheses and are a more robust test of outcomes than collapsing results into 1 metric. The results in Table 3 were provided as simply descriptive outcomes. It is also noted that the response to CBT at 24 weeks is less than seen in similar studies lasting 12 weeks perhaps reflecting the chronic relapsing nature of addiction (Anton et al., 2005; O’Malley et al., 1992; Project MATCH Research Group, 1998). As the CBT model has more contact than either of the other models, it is possible the effect relates more to therapeutic alliance and time in treatment. The results from this trial failed to demonstrate an effect of naltrexone over placebo. The relapse rates in the naltrexone-treated group are significantly greater than most published trials, perhaps related to the longer duration of the trial (Bouza et al., 2004; Srisurapanont and Jarusuraisin, 2005). However, there were relatively high rates of medication nonadherence over the course of this 24-week trial, and there was an association between drinking outcomes and medication adherence, such that medication adherent subjects had a longer time to first day of heavy drinking, but this effect did not differ between the medication and placebo groups. It is important to recognize that substantial reductions in alcohol use were achieved by the majority of participants. This was true even in the least therapeutic condition (medication clinic only plus placebo) in which the percentage of heavy-drinking days declined from 60 to 12% of the days. While the study failed to differentiate outcomes between BRENDA and medication clinic only, it would be inappropriate to conclude from these results that none of the 3 treatment arms were therapeutic as there were substantial improvements in outcomes and the design of the study did not include a control group that received no treatment.

The lack of overall naltrexone efficacy could be due to type II error; some literature reviews have demonstrated only modest between-group treatment differences from naltrexone (Kranzler et al., 2001; Streeton and Whelan, 2001). However, there is evidence to suggest that mixed findings in the literature could be due, at least in part, to predictable differences in patient responsiveness to naltrexone as well as adherence. The current trial was conducted as a classical randomized clinical trial designed to demonstrate the efficacy of the treatment components; however, several recent reports suggest that the effects of naltrexone are not universal and should be targeted toward certain populations. Prior work has suggested that family history may play a key role in response to naltrexone in placebo-controlled trials (King et al., 1997; Monterosso et al., 2001; Rohsenow, 2007 #6344). In addition, recent lines of investigation suggest that a genetic polymorphism may be associated with treatment response (Oslin et al., 2003). Compared with trials designed to examine individual response patterns, trials that select promising subgroups such as family history positive or those subjects with a particular genotype may be expected to demonstrate more consistent and stronger positive findings. Thus it is entirely possible that CBT may be a treatment with more general effects and naltrexone may have select efficacy in a smaller select group of individuals genetically disposed to differential opioid release during alcohol ingestion. If this is demonstrated in future trials, then we can begin to consider algorithms for treatment that incorporate genetics, efficacy, as well as patient preference.

The role of treatment adherence is also of interest in this study. The lack of an effect of the type of psychotherapy on medication adherence was disappointing and suggests that adherence to treatment is not simply determined by the treatment type but includes alternative explanations. While each of the treatment conditions allowed for discussion of medication adherence, the intervention specifically targeted to enhance adherence appeared to provide no better treatment adherence than the other conditions. One must also consider the use of 100 mg as a factor in the high rates of nonadherence, although there did not appear to be high rates of adverse events, except insomnia that was more common with naltrexone there were more naltrexone treated subjects who had dose reductions than placebo treated. This trial was substantially different from most of the efficacy trials in the designed duration. As nonadherence increases with time, the duration of the trial would impact the interaction between adherence and treatments on outcomes. To explore this issue, we investigated the temporal relationship between the first day of heavy drinking and first episode of medication nonadherence. The assumption is sometimes made that subjects start drinking heavily because they have stopped taking an effective medication, but it is also plausible that some patients stop taking medication because they determine that the medication is not working for them. That is, they start to drink heavily while taking the medication, and, seeing that the medication does not help them control the drinking, they stop the medication. The results from our post-hoc analysis of the temporal association of drinking and relapse highlight that, for a substantial number of participants (64%), relapse preceded nonadherence. Even when using the depot formulation in a placebo-controlled trial, only 64% of subjects received all 6 months of double-blind medication (Garbutt et al., 2005).

Another alternative to nonadherence would be the clinical practice of adaptive treatment. For example, once subjects begin to relapse while continuing to attend therapy, they could be reassigned to an alternative treatment plan such as a different or adjunctive medication or more intensive psychosocial therapy. Such adaptive designs in which treatment is adjusted for nonresponders, including sequential randomized designs, should be tested to see if they can improve subject adherence and outcome. The methodology exists for this type of study and allows for both estimates of the efficacy in the primary contrast as well as estimates of the adaptations (Collins et al., 2004;Murphy et al., 2007).

Limitations that may have affected the interpretation of the psychosocial effects include the lack of blinding and the potential therapeutic effects of the research staff. While attempts were initially made to blind research staff to the type of psychosocial intervention delivered, this proved futile as patients often mentioned what treatment they received. Thus, the outcome assessments were not conducted blind to psychosocial intervention, although the blind for medication assignment was maintained. The research staff also had frequent visits with each patient and in effect may have overwhelmed the lack of contact in the medication clinic only group. Finally, we relied on pill counts from blister cards to measure adherence. Although this method has been accepted as one of the better methods for clinical trials, it also likely represents an over-estimate of adherence as some subjects may simply discard their medications rather than take the medication (Pettinati et al., 2000).

Although the original intent of this trial was to test for medication by psychosocial intervention interactions, the sample size was sufficient only to test for very large effects and would only be testable if the main effects were significant. Therefore, it was not surprising to find a lack of evidence for a psychosocial intervention by medication by time effect. In addition to the sample size, the relatively high rates of nonadherence may have also accounted for the lack of interactive effects.

The nonlinear outcome results are also of interest. There appears to have been a number of subjects who improved at the end of the trial, particularly in the medication clinic only group. While there does not appear to be an obvious explanation to the effect, the presence of this improvement could have had a marked impact on the interpretation of the results.

In addition, self-report may call into question the reliability of the sequence of drinking and medication nonadherence. On the one hand, this latter concern could be partially mitigated by the lack of connection between the questions as they were asked of the subjects and our later juxtaposition of them. That is, the subjects were not directly asked which event occurred first, but this information was extracted from their separate reports of each type of event. More objective measures of medication adherence could increase the confidence in assessing the temporal sequence of drinking and medication nonadherence. Finally, this study focused specifically on alcohol-dependent patients without significant co-occurring mental health problems. While this is the most common pattern of illness in the community (Grant et al., 2004), it is not typical of the patients seen in specialty substance abuse clinics, and thus the results may be difficult to apply in those settings.

In summary, CBT was found to be more effective in the treatment of alcohol dependence over 24 weeks than the other psychosocial interventions. However, there was no evidence that adding naltrexone to a psychosocial intervention improved drinking outcomes. There was also a temporal relation between medication nonadherence and drinking that suggested that longer treatment trials may be problematic, particularly trials with a classical fixed randomized design that does not have the flexibility to adapt treatment for nonresponders. Also, studies of naltrexone that target specific patient subpopulations such as those with a family history are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse # AA 07517, National Institute on Mental Health (#) 1K08 MH01599-01, and National Institute on Drug Abuse P50 DA 12756 and P60 DA005186.

References

- Anton RF. New methodologies for pharmacological treatment trials for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:3A–9A. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P, Waid LR, Myrick H, Voronin K, Thevos A, Wang W, Woolson R. Naltrexone combined with either cognitive behavioral or motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:349–357. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000172071.81258.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, Latham PK, Malcolm RJ, Dias JK. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1758–1764. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouza C, Magro A, Munoz A, Amate JM. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2004;99:811–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chick J, Anton R, Checinski K, Croop R, Drummond DC, Farmer R, Labriola D, Marshall J, Moncrieff J, Morgan MY, Peters T, Ritson B. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:587–593. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prev Sci. 2004;5:185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croop RS, Faulkner EB, Labriola DF. The safety profile of naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism. Results from a multicenter usage study. The Naltrexone Usage Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240090013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger S. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. 2. Oxford University Press Inc; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, Loewy JW, Ehrich EW, Vivitrex Study G. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial [see comment] [erratum appears in JAMA. 2005 Apr 27;293(16):1978] JAMA. 2005;293:1617–1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Applications of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychol Methods. 1997;2:64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Heinala P, Alho H, Kiianmaa K, Lonnqvist J, Kuoppasalmi K, Sinclair JD. Targeted use of naltrexone without prior detoxification in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a factorial double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:287–292. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series. Vol. 2005. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AJ, Rounsaville B, Chang G, Schottenfeld RS, Meyer RE, O’Malley SS. Naltrexone, relapse prevention, and supportive therapy with alcoholics: an analysis of patient treatment matching. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1044–1053. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadden R, Carroll K, Donovan D, Cooney N, Monti P, Abrams D, Litt M, Hester R, editors. Cognitive Behavioral Coping Skills Therapy Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating Individuals with Alcohol Abuse and Dependence. NIH; Rockville: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Volpicelli JR, Frazer A, O’Brien CP, King AC, Volpicelli JR, Frazer A, O’Brien CP. Effect of naltrexone on subjective alcohol response in subjects at high and low risk for future alcohol dependence. Psychopharmacology. 1997;129:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s002130050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler H, Modesto-Lowe V, VanKirk J. Naltrexone vs. nefazadone for treatment of alcohol dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:493–503. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Van Kirk J, Kranzler HR, Van Kirk J. Efficacy of naltrexone and acamprosate for alcoholism treatment: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1335–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study G. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence [comment] N Engl JMed. 2001;345:1734–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latt NC, Jurd S, Houseman J, Wutzke SE. Naltrexone in alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial of effectiveness in a standard clinical setting. Med J Aust. 2002;176:530–534. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul ME, Wand GS, Rohde C, Lee SM. Serum 6-beta-naltrexol levels are related to alcohol responses in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1385–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, Tonigan J, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An Instrument for assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse. Vol. 4. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Monterosso JR, Flannery BA, Pettinati HM, Oslin DW, Rukstalis M, O’Brien CP, Volpicelli JR. Predicting treatment response to naltrexone: the influence of craving and family history. Am J Addict. 2001;10:258–268. doi: 10.1080/105504901750532148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Swift RM, Gulliver SB, Colby SM, Mueller TI, Brown RA, Gordon A, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, Asher MK. Naltrexone and cue exposure with coping and communication skills training for alcoholics: treatment process and 1-year outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1634–1647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris PL, Hopwood M, Whelan G, Gardiner J, Drummond E. Naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial [comment] Addiction. 2001;96:1565–1573. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA, Lynch KG, Oslin D, McKay JR, TenHave T, Murphy SA, Lynch KG, Oslin D, McKay JR, TenHave T. Developing adaptive treatment strategies in substance abuse research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 2):S24–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelkerke N, Fidler V, Bernsen R, Borgdorff M. Estimating treatment effects in randomized clinical trials in the presence of non-compliance. Stat Med. 2000;19:1849–1864. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20000730)19:14<1849::aid-sim506>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Rode S, Schottenfeld R, Meyer RE, Rounsaville B. Six-month follow-up of naltrexone and psychotherapy for alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:217–224. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley S, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Schottenfeld RS, Meyer RE, Rounsaville B. Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:881–887. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Rounsaville BJ, Farren C, Namkoong K, Wu R, Robinson J, O’Connor PG. Initial and maintenance naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence using primary care vs specialty care: a nested sequence of 3 randomized trials. Arch InternMed. 2003;163:1695–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, Pettinati H, Gelernter J, Volpicelli JR, O’Brien CP. A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1546–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin D, Liberto JG, O’Brien J, Krois S, Norbeck J. Naltrexone as an adjunctive treatment for older patients with alcohol dependence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5:324–332. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199700540-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park T, Lee S-Y. Simple pattern-mixture models for longitudinal data with missing observations. StatMed. 1999;18:2933–2941. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19991115)18:21<2933::aid-sim233>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP, Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Pierce JD, Jr, O’Brien CP. Improving naltrexone response: an intervention for medical practitioners to enhance medication compliance in alcohol dependent patients. J Addict Dis. 2000;19:71–83. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati H, Weiss R, Miller W, Donovan D, Ernst DBJR. DHHS Publication # 04–5289. NIAAA; Bethesda, MD: 2004. Medical Management Treatment Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Medically Trained Clinicians Providing Pharmacotherapy as Part of the Treatment for Alcohol Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Miranda R, Jr, McGeary JE, Monti PM. Family history and antisocial traits moderate naltrexone’s effects on heavy drinking in alcoholics. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:272–281. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small D, TenHave T, Joffe M, Cheng J. Random effects logistic models for analyzing efficacy of a longitudinal randomized treatment with non-adherence. Stat Med. 2005;25:1981–2007. doi: 10.1002/sim.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. In: Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption, in Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Litten R, Allen J, editors. Humana Press Inc; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M, Gloria L, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1461145704004997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeton C, Whelan G. Naltrexone, a relapse prevention maintenance treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36:544–552. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O’Brien CP, Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence [see comment] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP. BRENDA Manual: Compliance Enhancement Techniques with Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol and Drug Dependence. Gilford Press; Philadelphia, PA: 1997a. [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli JR, Rhines KC, Rhines JS, Volpicelli LA, Alterman AI, O’Brien CP, Volpicelli JR, Rhines KC, Rhines JS, Volpicelli LA, Alterman AI, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone and alcohol dependence. Role of subject compliance [see comment] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997b;54:737–742. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200071010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerts E, Kim Y, Wand G, Dannals R, Lee J, Frost J, McCaul M. Differences in Delta- and Mu-Opioid Receptor Blockade Measured by Positron Emission Tomography in Naltrexone-Treated Recently Abstinent Alcohol-Dependent Subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;33:653–665. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]