Gelatinase B has been suggested to intervene at different stages of the cyclical changes in female reproduction (1–3): in the menstrual cycle, ovulation, implantation, parturition, and involution of the mammary glands after lactation. Gelatinase B has also been implicated in the process of growth and development of the embryo (4, 5). So far, the only reported spontaneous phenotype of gelatinase B deficiency is a delayed ossification of the growth plate in long bones (6). Most other phenotypes of gelatinase B are induced tissue reactions of the skin (7), the lung (8), the central nervous system or bone (9), and the aortic wall (10). Is there any spontaneous effect of gelatinase B ablation on reproductive capacity?

Gelatinase B–deficient mice were generated by a functional knockout of the active and zinc-binding domain of MMP-9 as previously described (9). In the three reports published to date (6, 9, 11), which described structurally distinct null alleles in the gene, gelatinase B–deficient mice were found to reproduce. However, in the course of studying the induction of autoimmune diseases in these animals, we noted a significantly diminished breeding efficiency of the gelatinase B–deficient mice as compared with wild-type controls.

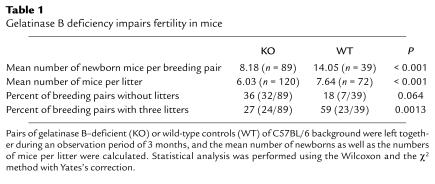

During a test period of 3 months, the number of mice born per breeding pair is significantly lower in the gelatinase B–deficient than in the wild-type mice. In addition, the individual litters in knockout mice are smaller, and the percentage of infertile breeding pairs is elevated in the gelatinase B–deficient mice, whereas maximal litter numbers were observed in the wild-type mice (Table 1). The percentages of breeding pairs with 0, 1, 2, or 3 litters were respectively 18, 5, 18, and 59 for the wild-type mice (n = 39), versus 36, 20, 17, and 27 for the gelatinase B–deficient mice (n = 89) (P = 0.007, χ2 with Yates’s correction = 12.10, 4 × 2 contingency table, 3 degrees of freedom). Control and knockout mice were bred on C57BL/6 background. We observed a quantitatively similar suppression of fertility in gelatinase B–deficient mating pairs whether we compared MMP-9–/– animals with their wild-type littermates or with wild-type breeding pairs that carried the pure C57BL/6 background genotype. Hence, the differences seen in fertility are not caused by genetic background effects but, indeed, by gelatinase B deficiency. Further studies are required to elucidate whether this spontaneous phenotype may be attributed to male or to female fertility.

Table 1.

Gelatinase B deficiency impairs fertility in mice

Matings of heterozygous mice resulted in the expected mendelian frequency of MMP-9+/+ (101/359, 28.1%), MMP-9–/– (81/359, 22.6%) and MMP-9+/– (177/359, 49.3%) mice (9), suggesting that embryonic and fetal development of homozygous mutant mice were not impaired, as also observed by Vu et al. (6).

Based on the combination of a reduced breeding efficiency of homozygous gelatinase B–deficient mice and the occurrence of the expected mendelian frequency of MMP-9+/+, MMP-9–/–, and MMP-9+/– mice in heterozygous matings, we conclude that decreased fertility is a spontaneous phenotype of gelatinase B deficiency. This finding reinforces the role of gelatinase B in the establishment and maintenance of a normal pregnancy and suggests that influencing gelatinase B activity may be a target in birth control. In addition, decreased fertility is anticipated in the treatment with nonselective and selective MMP-inhibitory drugs that are currently used in clinical trials for inflammatory and neoplastic diseases.

Acknowledgments

B. Dubois is a research assistant of the Fund for Scientific Research (Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek–Vlaanderen [FWO-Vlaanderen]). This work was supported by the Charcot Foundation, Fortis FB Insurances, and the FWO-Vlaanderen in Belgium, and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants SFB 405 and EU BIO4-CT-96007) and the Volkswagen Foundation (grant I/72-422) in Germany. The authors thank Jan Mertens and Marcel Huybrechts for excellent animal care in the specific pathogen–free facility and J. Van Damme for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jeziorska M, Nagase H, Salamonsen LA, Woolley DE. Immunolocalization of the matrix metalloproteinases gelatinase B and stromelysin 1 in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. J Reprod Fertil. 1996;107:43–51. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1070043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Librach CL, et al. 92-kD type IV collagenase mediates invasion of human cytotrophoblasts. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:437–449. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vadillo-Ortega F, et al. 92-kd type IV collagenase (matrix metalloproteinase-9) activity in human amniochorion increases with labor. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:148–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canete SR, Gui YH, Linask KK, Muschel RJ. Developmental expression of MMP-9 (gelatinase B) mRNA in mouse embryos. Dev Dyn. 1995;204:30–40. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002040105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh LYS, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9/gelatinase B is required for process outgrowth by oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8464–8475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08464.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vu TH, et al. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Z, et al. Gelatinase B-deficient mice are resistant to experimental bullous pemphigoid. J Exp Med. 1998;188:475–482. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase deficiencies affect contact hypersensitivity: stromelysin-1 deficiency prevents the response and gelatinase B deficiency prolongs the response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6885–6889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois B, et al. Resistance of young gelatinase B-deficient mice to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and necrotizing tail lesions. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1507–1515. doi: 10.1172/JCI6886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pyo R, et al. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1641–1649. doi: 10.1172/JCI8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itoh T, et al. Experimental metastasis is suppressed in MMP-9-deficient mice. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:177–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1006603723759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]