Abstract

Objectives

In patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), the presence of non-caseating mucosal granuloma is sufficient for diagnosing Crohn disease (CD) and may represent a specific immune response or microbial-host interaction. The cause of granulomas in CD is unknown and their association with the intestinal microbiota has not been addressed with high-throughput methodologies.

Methods

The mucosal microbiota from three different pediatric centers was studied with 454 pyrosequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the fungal small subunit (SSU) ribosomal region in transverse colonic biopsy specimens from 26 controls and 15 treatment naïve pediatric CD cases. Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) was tested with real-time PCR. The correlation of granulomatous inflammation with C-reactive protein (CRP) was expanded to 86 treatment naïve CD cases.

Results

The CD microbiota separated from controls by distance based redundancy analysis (dbRDA; p=0.035). Mucosal granulomata found in any portion of the intestinal tract associated with an augmented colonic bacterial microbiota divergence (p=0.013). The granuloma based microbiota separation persisted even when research center bias was eliminated (p=0.04). Decreased Roseburia and Ruminococcus in granulomatous CD were important in this separation. However, principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) did not reveal partitioning of the groups. CRP levels above 1mg/dl predicted the presence of mucosal granulomata (OR: 28 [6–134.32]; 73% sensitivity, 91% specificity).

Conclusions

Granulomatous CD associates with microbiota separation and CRP elevation in treatment naïve children. However, overall dysbiosis in pediatric CD appears rather limited. Geographical/center bias should be accounted for in future multi-center microbiota studies.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, microbiota, fungi, granuloma, inflammatory bowel disease

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are disorders that affect more than four million people worldwide (1). The incidence of IBD has significantly increased globally over the last century and recent observations indicate their ongoing emergence (2, 3). The diagnosis of IBD is based on clinical history, physical examination, serology, radiological studies, endoscopy, and histology (4). While no ideal non-invasive biomarker exists for IBD, the assessment of C-reactive protein (CRP) is commonly employed during the diagnostic process. CRP serum levels have shown value in indicating prognosis, response to therapy, and disease activity in CD (5–7).

About 25% of IBD patients present during childhood or adolescence (8) with somewhat different disease characteristics than adults (9). The distinction between CD and UC in as many as 15% of adult and 20% of pediatric IBD cases can be challenging (10). The occurrence of a granuloma is pathognomic of CD and is helpful in distinguishing Crohn colitis from UC. The cause of non-caseating granulomas in CD is unknown and their presence has not been conclusively linked to specific microorganisms, including Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) (11, 12). In the meantime, the intestinal microbiota plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of CD where disease phenotype as well as host genotype are associated with specific shifts in composition (13) depending on the location (ileum, colon) and sample (feces, mucosa) examined (14, 15). The fecal microbiota differs from mucosal (16) with the later likely being more relevant for intestinal immunomodulation (17).

The advancement of culture independent methodologies has shed light on the complexity and dynamic structure of the human microbiota. However, variation between interrogation methods, sampling, and the IBD populations studied has confounded the clear characterization of disease associated microbiota and its potential pathogenic role (18). Moreover, the possible confounding effects of longstanding inflammation and ongoing anti-inflammatory treatment have rarely been accounted for in microbiota studies of IBD. In the meantime, recent findings demonstrated the significant microbiota modifying effects of frequently used pharmacotherapy in the disease group (19).

Pediatric IBD cases present a unique opportunity to examine the biological components of IBD pathogenesis following a suspected shorter duration of the disease than in adults. Furthermore, if samples are obtained at the time of the diagnostic procedure, subjects will most likely be treatment naïve. The largest microbiota investigation on pediatric colonic mucosal samples from IBD patients with limited medication exposure was conducted on 12 CD cases and 17 controls with bacterial cultures and real-time PCR of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene for 14 separate species (20). While yeast are acknowledged as potential pathogens in CD (21), high-throughput fungal metagenomic analyses have not been applied to pediatric cases of IBD.

In this study, we examined transverse colonic mucosal biopsy samples by massively-parallel pyrosequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the fungal small subunit (SSU) ribosomal region in 15 treatment naïve pediatric CD cases and 26 controls. The microbiota associations of CD were correlated with histological, clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Samples

Control patients (abdominal pain: 8; irritable bowel syndrome: 4; hematochezia: 3; solitary juvenile polyp: 3; diarrhea: 2; perianal fissure: 2; GERD: 2; and 1 of each: gastritis, healthy [polyposis in sister]) were recruited prior to endoscopy following informed consent through the institutional review board (IRB) approved tissue banks of the Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic (EK-1796/08); the Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Consortium Registry at the Baylor College of Medicine (H-17654); and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH; 2009p001287) (table 1). Only patients with grossly and histologically normal mucosa at colonoscopy were designated as controls.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of treatment naïve Crohn disease patients and controls

| Age (years) | Gender | Ethnicity | Montreal classification

|

Terminal ileum intubation | # biopsy | Site of granuloma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Location | B | ||||||||

| Crohn disease | Granulomas | 15.6 | F | AA | A1 | L3 L4 | B1 | yes | 32 | >4 sites |

| 13.5 | M | C | A1 | L2 L4 | B1 | yes | 29 | Duo, sigmoid | ||

| 16.3 | F | C | A2 | L3 L4 | B1 | yes | 71 | Stom, TI, Trans, RS | ||

| 13 | F | C | A1 | L3 L4 | B1 | yes | 43 | Stom, TI, Des, RS | ||

| 17.3 | M | AA | A2 | L3 L4 | B1 | yes | 43 | Des | ||

| 15 | F | C | A1 | L2 L4 | B2 | no | 16 | Sigmoid | ||

| 8.11 | F | C | A1 | L3 L4 | B1 | yes | 25 | Rectum | ||

| 16.9* | M | C | A2 | L3 L4 | B1 | yes | 30 | >4 sites | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| No granulomas | 7.1 | F | C | A1 | L2 L4 | B1 | no | 29 | ||

| 16.9 | M | C | A2 | L3 | B1 | yes | 25 | |||

| 8.1 | F | C | A1 | L2 L4 | B1 | yes | 30 | |||

| 15 | M | C | A1 | L3 L4 | B1 | yes | 28 | |||

| 16.1 | M | C | A2 | L3 | B1 | yes | 32 | |||

| 9.6* | M | C | A1 | L3 | B1 | yes | 15 | |||

| 13* | F | C | A1 | L2 | B2 | no | 6 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Control | Center | Diagnosis | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Baylor | 5 | M | C | Juvenile polyp | ||||||

| 15 | F | C | Abdominal pain | |||||||

| 8 | F | C | Abdominal pain | |||||||

| 13 | M | AA | Abdominal pain | |||||||

| 5 | F | C | Abdominal pain | |||||||

| 8 | F | C | Hematochezia | |||||||

| 12 | M | C | Diarrhea | |||||||

| 13 | M | C | Abdominal pain | |||||||

| 10 | M | C | Abdominal pain | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| MGH | 14 | F | C | Diarrhea | ||||||

| 17 | F | C | Hematochezia | |||||||

| 11 | F | C | Gastritis | |||||||

| 11 | F | C | Perianal fissure | |||||||

| 12 | M | U | GERD | |||||||

| 16 | M | C | IBS | |||||||

| 18 | M | C | GERD | |||||||

| 11 | M | C | IBS | |||||||

| 18 | M | C | Abdominal pain | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| CZ | 3.5 | M | C | Juvenile polyp | ||||||

| 13.5 | F | C | IBS | |||||||

| 14 | M | C | Juvenile polyp | |||||||

| 15 | F | C | Hematochezia | |||||||

| 16.5 | M | C | Perianal fissure | |||||||

| 17 | F | C | Abdominal pain | |||||||

| 17 | F | C | IBS | |||||||

| 17.5 | F | C | Healthy | |||||||

Baylor: Baylor College of Medicine; MGH: Massachusetts General Hospital, CZ: Czech Republic; F: female; M: male; AA: African-American; C: Caucasian; U: unknown; A: age; B: behavior. Montreal classification (23) was based on microscopic findings. The granuloma positive group had gastric involvement more commonly than granuloma negative patients (p=0.026). Terminal ileal (TI) sampling and the number of biopsies analyzed by traditional histology did not differ significantly between the granuloma positive and negative groups. Stom: stomach; duo: duodenum; trans: transverse colon; des: descending colon; RS: rectosigmoid colon.

Crohn disease patients from MGH, others were from Baylor. GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome

Treatment naïve CD cases were recruited prior to their first diagnostic colonoscopy in Baylor and MGH whose disease was determined based upon clinical, biochemical and histological characteristics. Neither CD patients nor controls reported the use of antibiotics within 6 months of sampling. Transverse colonic mucosal samples were snap frozen on dry ice or in liquid N2 immediately after biopsy and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Table 1 shows demographic characteristics and Montreal classification of the patients studied. Age, gender, ethnicity and disease location was similar between granuloma positive and negative patients. Age and gender did not differ significantly between CD and controls. Studies indicate that the proximal and distal colonic microbiota may differ (22). Therefore, we aimed to interrogate the middle/average of the mucosal bacterial community by studying transverse colonic mucosa samples.

CRP correlation was extended to 86 treatment naïve pediatric CD cases. Granulomatous CD was defined as the presence of granuloma or a distinct giant cell in at least one biopsy specimen. Histological severity of inflammation was graded between 0–3 (none to severe) based on the pathology reports incorporating epithelial damage, architectural distortion, and white blood cell infiltration of the lamina propria and epithelium by a physician observer (SM). Only patients who had both esophago-gastro-duodensocopy and colonoscopy evaluation were included. Only CRP values obtained 1 week prior to or at endoscopy were considered. Histological assessment of terminal ileum was made at similar frequency between granulomatous and non-granulomatous CD groups.

DNA Extraction

After thawing, the colonic mucosal biopsies were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 seconds and resuspended in 500μl RLT buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) (with β-mercaptoethanol). Sterile 5mm steel beads (Qiagen) and 500μl sterile 0.1mm glass beads (Scientific Industries, Inc., NY, USA) were added for complete bacterial lyses in a Qiagen TissueLyser (Qiagen), run at 30Hz for 5min. Samples were centrifuged briefly, 350 μl of RTL and 200μl of 100% ethanol were added to a 100μl aliquot of the sample supernatant. This mixture was added to a DNA spin column, and DNA recovery protocols were followed as instructed in the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) starting at step 5 of the Tissue Protocol. DNA was eluted from the column with 30μl water and samples were diluted accordingly to a final concentration of 20ng/μl. DNA samples were quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nyxor Biotech, Paris, France).

Massively Parallel bTEFAP

Bacterial tag-encoded FLX-Titanium amplicon pyrosequencing (bTEFAP) was performed as described previously (24). (For details, see supplementary Methods, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A115).

Bacterial Diversity Data Analysis

Prior to analysis, sequences shorter than 300bp were removed and sequences were depleted of any non-bacterial ribosome sequences and chimeras using the Black Box Chimera Check software B2C2 (described and freely available at http://www.researchandtesting.com/B2C2.html). To determine the identity of bacteria in the remaining sequences, they were first queried using a distributed BLASTn.NET algorithm (25) against a database of high quality 16S rRNA bacterial sequences derived from NCBI. (For details, see supplementary Methods, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A115).

Fungal Diversity Analysis

Multivariate analysis of both bacteria and fungi were based on measures of multivariate distance (i.e., dbRDA). However, the specific distance measure most used for bacteria (UniFrac) was not available for fungi. Therefore, the Bray-Curtis distance measure was used in this case, which is a robust measure of distance for community datasets (26). The primer set to detect fungal small subunit (SSU) ribosomal region was as follows: SSU-F: 5′-TGG AGG GCA AGT CTG GTG-3′; SSU-R: 5′-TCG GCA TAG TTT ATG GTT AAG-3′. Bar-coding, quality filtration and taxonomic assignment were performed as in the bacterial analyses.

Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) Testing

The DNA extraction steps for MAP samples were the same as for the bacterial diversity testing. The only difference was that we used Qiagen TissueLyser to run at 30Hz for 20min to break MAP cells. The designed MAP primers and probe were as follow: MAPIS-F, 5′-TGG GTT GAT CTG GAC AAT GAC GGT-3′; MAPIS-R, 5′-TAA CCA TGC AGT AAT GGT CGG CCT-3′; MAPIS-probe, 5′-/56-FAM/TAC GGA GGT GGT TGT GGC ACA A/3IABkFQ/-3′. MAP ATCC strains (19689, 19851, 43544, 15769, 19074, 25219) were used as positive controls, and Mycobacterium intracellulare ATCC strains (13950, 16985, 25122) were used to test primer cross reaction. The quantitative real-time PCRs were performed by a Roche Light Cycler 480. The PCR reactions were as follows: deactivation, 95°C for 10sec; amplification, 35 cycles of 95°C for 15sec, 60°C for 1min (27).

Further Statistical and Bioinformatic Analysis

Unpaired, two tailed t-tests, odds ratio and two sided Fischer’s exact test calculations were also utilized in the group comparisons. Statistical significance was declared at p<0.05. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Crohn disease associates with significant bacterial microbiota separation

Distance based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) showed significant separation between the CD associated colonic mucosal microbiota and the microbiota of controls (p=0.035; figure 1A). The most abundant genera differences were in Roseburia (decrease) Sutterella (increase) Eubacterium (decrease) and Subdoligranulum (decrease) in CD compared to control (supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A116). Interestingly, 9 out of the 15 CD samples separated more distantly from controls (figure 1A).

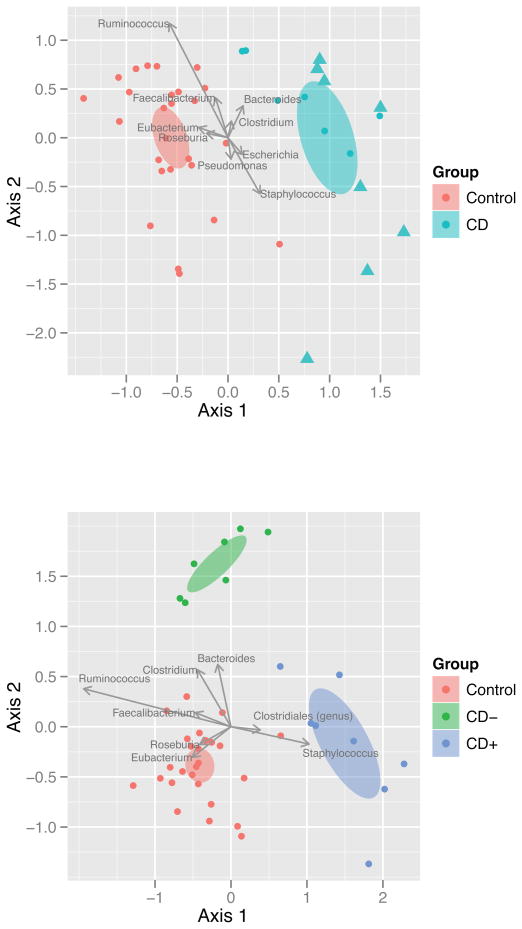

Figure 1. Distance based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) biplots of bacterial genera. Upper panel.

Biplot of the dbRDA results for bacteria (genera) comparing the control (C, red) and Crohn disease (CD, blue) groups. Ellipses represent the 95% confidence interval around group centroids. Arrows indicate the contribution of individual taxa to the dbRDA axes, and only those taxa with the largest contributions are shown. CD patient samples designated with triangles had granuloma detected in their intestinal mucosal biopsies. Granulomatous CD patients were observed to separate more distinctly from controls than non-granulomatous CD. There was only one non-granulomatous CD sample, which separated with the granulomatous samples (i.e.: outside of the 95% CD confidence interval away from controls: dot among triangles: total of 9 CD samples [1 non-granulomatous, 8 granulomatous] parting more than the other 6 non-granulomatous samples). C to CD separation was significant (p=0.035). Lower panel: Biplot of the dbRDA results for bacteria (genera) comparing the control (C, red), CD with granuloma (CD+, blue), and CD without granuloma (CD−, green) groups. Partitioning between these groups was more significant than (p=0.013) between control and CD alone.

Mucosal granuloma indicates distinct microbiota separation in CD

When the clinical and histological data of the 9 CD patients with more distinct microbiota separation was reviewed, the only significant finding was the presence of granuloma or a distinct giant cell in at least one biopsy sample from either the upper or the lower gastrointestinal tract in 8 out of the 9 patients (figure 1A). None of the other 6 patients in the study whose microbiota separated less distinctly had granuloma or giant cell observed. The presence of granuloma significantly predicted a discrete colonic mucosal microbiota separation in CD (p=0.0014) with 88.8% sensitivity and 100% specificity. dbRDA incorporating the presence or absence of granuloma supported this observation since the microbiota separation was more prominent when this histological parameter was taken into account (p=0.013, figure 1B). In the meantime, principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) did not show significant microbiota divergence between the groups (supplementary Fig 1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117) revealing the utility of dbRDA when limited dysbiosis is present in association with disease, or disease subtypes.

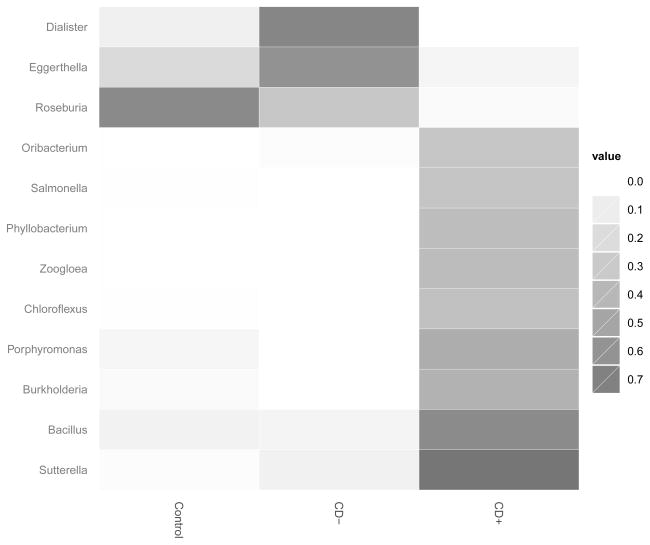

Heatmap of the indicator species analysis at the genera (figure 2) and the species (supplementary Fig 2, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117) level showed that CD patients with granuloma had a higher number of genera and species significantly differentiating the colonic mucosal microbiota from controls than patients without granuloma. ANOVA results for the genera and species comparisons between granuloma positive-, negative CD and controls are presented in supplementary Tables 2 and 3 (http://links.lww.com/MPG/A118).

Figure 2. Heatmap summary of the indicator species analysis performed on the bacterial microbiota at the genera level.

Only those genera that contained indicator values with p<0.05 are shown. The heatmap values are indicator scores, calculated based upon the relative frequency and the relative average abundance in the groups. Only abundance based numeric comparisons for this figure are provided in supplementary tables 2 to 4. C: control group; CD−: granuloma negative Crohn disease; CD+: granuloma positive Crohn disease.

While there were 32 genera differing (with Student t test p<0.05) between granuloma positive CD patients and controls (supplementary Table 4, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119), only 4 of such could be detected in granuloma negative cases (supplementary Table 5, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). None of the 4 genera separating granuloma negative CD from controls represented more than 0.4% of the bacterial populations in any of the samples studied.

The most prominent genera distinguishing granulomatous CD from non-granulomatous were: Ruminococcus, Roseburia, Eggerthella (decrease) and Porphyromonas (increase) (figure 2 and supplementary table 6 [http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119]). There was a trend for the genera Faecalibacterium to be decreased in the transverse colonic mucosa of granulomatous CD patients compared to granuloma negative ones (supplementary table 6 [http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119]; p=0.073). Additionally, Dialister (figure 2) was absent in 7 out of 8 granuloma positive cases, but detectable in 6 out of 7 granuloma negative CD cases (OR: 0.0238 [0.0012 to 0.4679]; p=0.0087). On the contrary, Porphyromonas was, present in 5 out of 8 granulomatous CD patients, but was undetectable in the granuloma negative cases (p=0.026). Histological severity of inflammation in the transverse colon (in adjacent biopsies to ones analyzed for microbiota) was not significantly different between granuloma positive and negative cases (p=0.212). Only the abundance of Ruminococcus showed significant correlation (inverse correlation: supplementary Fig 3, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117) with microscopic inflammation among the above 6 genera (the others had no significant correlation with inflammation, not shown).

There were no species differentiating granuloma positive from negative CD. However, there were 16 species differing between CD and controls (supplementary Table 7, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). When the presence of granuloma was taken into account, there were 61 species significantly differing in average abundance between granulomatous CD and controls (supplementary Table 8, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119) while only 18 such could be detected between granuloma negative CD and controls (supplementary Table 9, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). Notably, Ruminococcus gnavus was significantly increased in granuloma negative CD only (supplementary Table 7, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, while detected and distinguished by our microbiota analysis, was not among the significantly partitioning species in any of the comparisons.

Bacterial richness and diversity analyses did not reveal significant differences between control, granuloma positive, and negative groups (supplementary Figs 4–6, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117).

Fungal Malassezia genus associates with granuloma positive CD

Fungal dbRDA showed no significant separation between controls and granuloma positive or negative cases of CD (supplementary Fig 7, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117). However, the genus Malassezia was significantly associated with granulomatous CD. ANOVA for fungal genera showed only Malassezia to differentiate significantly between the observed groups (FDR=0.02). A significantly higher proportion of granulomatous CD patients had Malassezia exceeding a cutoff value of 1% (6 out of 7 [one sample could not be amplified]; OR: 25.2 [2.45–259.24], p=0.0025) compared to control (5 out of 26). Samples from granuloma positive CD patients more commonly had Malassezia >1% compared to granuloma negative cases (2 out of 7) in the transverse colonic mucosa as well (OR:15 [1.03–218.31], p=0.102).

MAP was not found in the biopsy specimens

We tested for the presence of MAP by real-time PCR. None of the samples studied was positive.

Significant geographical bias

Center and geographic bias was not addressed during the initial evaluations with the intention to identify common microbiota associations (independently from geographical location) of CD in industrialized countries. However, control and disease samples were skewed by sites (Table 1). Therefore, geographic effects on microbiota composition (28) may have significantly influenced our results. Indeed, while PCoA did not separate the sites, dbRDA did (supplementary Fig 8, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117), indicating potential center bias. Consequently, we separately analyzed the results from the center from which most samples were obtained (Baylor). Geographical/center bias on microbiota composition could have resulted from multiple factors including genetic and dietary differences between the populations studied, variation in bowel cleansing regimens (29), and differing methods of sample freezing (dry ice vs. liquid nitrogen).

Center bias modified the results of bacterial genus and species comparisons between the control, CD, and granuloma based comparisons. Nevertheless, granuloma based microbiota separation persisted (p=0.04; supplementary Fig 9, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117) and several bacterial genera and species remained different between the groups of the Baylor cohort (supplementary Tables 10–16, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). Namely, Roseburia and Eubacterium were consistently decreased in CD mucosa (supplementary Table 10, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119), while Roseburia and Ruminococcus (including R. bromii, callidus, gnavus, obeum, and yet unclassified Ruminococcus species) were less abundant in granulomatous CD than in non-granulomatous, with Porphyromonas being more abundant in the colonic mucosa of granuloma positive patients (supplementary Table 12, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). At the species level, Eubacterium ramulus and Roseburia species (sp, yet unclassified Roseburia species) were consistently decreased in CD (supplementary Table 13, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). Granulomatous CD cases were mostly the reason for this separation in respect of Roseburia sp (supplementary Tables 14 and 16, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). Importantly, Dialister was less than 0.045% abundant in all granulomatous CD samples, while more than 0.07% in all non-granulomatous CD cases in the Baylor cohort (p=0.0013). Dialister invisus specifically was less abundant (<0.044%) in all granulomatous CD samples, while it was present at 0.044% or more in non-granulomatous CD (p=0.0152).

When the Baylor cohort was analyzed by fungal metagenomics, the association of Malassezia with granulomatous CD was less prominent (5 out of 6 CD+ cases >1%, while 3 out of 9 in control; p=0.12). However, Saccharomyces (2 out of 11 in CD, 8 out of 9 in control; p=0.0055) and Candida (3 out of 11 CD, 7 out of 9 control; p=0.07) were surprisingly less frequently detectable in all the Baylor CD samples (same between granulomatous and non-granulomatous) than controls. These findings pertained to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (detectable in 2 out of 11 in CD, 8 out of 9 in control; p=0.0055) and Candida albicans (detectable in 1 out of 11 in CD, 5 out of 9 in control; p<0.05) as well. These findings warrant further investigation since opposing results (i.e. increased abundance of Candida albicans specifically) were obtained from mouth swabs and stool specimens from CD patients and family members (30).

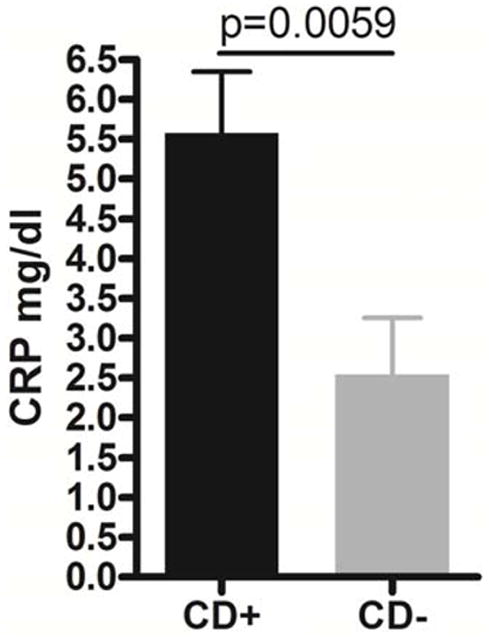

Mucosal granuloma is predicted by CRP levels in treatment naïve pediatric CD

When the clinical and laboratory parameters of the CD patients were compared, the patients with granulomatous CD had a trend for higher levels of serum CRP than patients without granuloma. We decided to use an arbitrary cutoff value of CRP (> 1mg/dl). By this means, a CRP > 1mg/dl predicted granulomatous CD by 80% sensitivity and 100% specificity in the microbiota study cohort (p=0.007). This level of CRP would have forecasted the observed more significant microbiota separation as well (OR: 16 [1.09–243.26]; p=0.089; 80% sensitivity, 80% specificity). The analysis was extended to a larger population of treatment naïve pediatric CD cases (86 patients, 56% of whom had granuloma/giant cell detected in at least 1 biopsy sample from the upper or the lower intestine). Within this larger population CRP > 1mg/dl significantly predicted granulomatous CD (OR: 28 [6–134.32]; p<0.00001; 73% sensitivity, 91% specificity). The average level of serum CRP was also significantly higher in the granulomatous CD group than in patients without granuloma (p=0.0059; figure 3). CRP testing for the 86 patients was performed in more than 4 different laboratories. However, CRP for 53 patients was tested in the same laboratory. If we examined only these cases, sensitivity (76%) and specificity (100%) for CRP > 1mg/dl predicting granulomatous Crohn disease increased (p<0.00001) compared to the collective cohort tested in multiple laboratories.

Figure 3. C-reactive protein (CRP) results.

CRP levels were higher (average 5.58 mg/dl) in granulomatous CD (CD+) than in patients without granuloma (CD−; average 2.54 mg/dl). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

The commensal microbiota is recognized to play an important role in a number of common human disorders including IBD (31–33). In the meantime, it is extremely difficult to overcome or incorporate the tremendous number of confounding variables, which characterize IBD focused clinical microbiota research (31). Therefore, the pathogenic role of IBD related dysbiosis and its potential therapeutic implications remain questionable (32).

In this study we analyzed pediatric transverse colonic mucosal biopsy samples from treatment naïve CD cases and controls, which enabled us to overcome several of the potential confounding issues of microbiota analysis in IBD, such as: examining a clinical subpopulation of patients (9) (early onset, with limited time for chronic inflammation); elimination of treatment bias (19); studying the mucosa associated microbiota, relevant for intestinal immunomodulation (17); and avoiding colonic location dependent microbiota variation (16). However, several limitations of our analysis are still present: (i) small sample size arising from the strict selection of patients; (ii) the nature of the control population, for whom a colonoscopy was indicated and a number of whom may have dysbiosis compared to healthy children regardless of having no obvious intestinal inflammation (34); (iii) lack of data regarding specific host genetic factors, such as polymorphisms in IBD susceptibility genes, which can associate with microbiota variation (13, 15); iv: significant center bias according to dbRDA. Nevertheless, our data suggest a microbiota separation within pediatric CD colonic mucosa (figure 1) that is modulated by the presence of granulomatous inflammation in any part of the intestinal tract independently from geographic bias (figure 1 and supplementary figure 8, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117). In a similar study of colonic mucosal samples from adult patients, only about 30% of CD cases separated from controls (35). However, the latter study tested mucosal samples from surgical cases (likely manifesting in patients with long lasting and/or more aggressive inflammation) without accounting for the effects of treatment, and utilizing a control population of largely (62%) colon cancer patients who themselves may have significant dysbiosis (36). In addition, whereas we directly tested for differences in the microbiota (using dbRDA), they did not (using PCoA to summarize overall variation). In fact, direct comparison between the PCoAs of the Frank et al. study (35) and ours (supplementary figure 1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117) indicates an even less prominent dysbiosis in treatment naïve pediatric CD than in the chronically treated, adult, surgical cases. The limited dysbiosis is further emphasized by the fact that none of the direct taxa comparisons in this study were significant after correcting for multiple tests (supplementary Tables 1–16, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A116, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A118, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119). However, this latter result may be a consequence of the small sample sizes originating from the challenges in obtaining treatment naïve samples. Therefore, the direct taxa comparisons represent only trends, which need to be verified in further studies with larger sample sizes.

We also detected a significant correlation between granulomatous CD and colonic mucosal microbiota variation by dbRDAs. Granuloma is a pathognomic feature of CD in the clinical setting of IBD and can be detected in 21–60% of patients, with a higher frequency in children (10, 37, 38). The pathogenesis of granuloma formation in CD is unknown, although some studies hypothesize that specific bacterial components may play role (39). Granulomas in pediatric CD have been associated with an increased incidence of perianal disease and gastritis (10). MAP has been detected in a higher number of pediatric patients with granulomatous CD than controls (40), but these observations were not confirmed with similar methodology from adult CD patients in biopsies containing mucosal granuloma (12). Therefore, the importance of MAP in regards to IBD pathogenesis remains questionable.

Roseburia was decreased in the colonic mucosa of our CD proband, which was largely attributable to the subjects with granuloma irrespective from geographic bias. This was not observed by Willing and colleagues who only found significant decreases of this genus in the ileum and feces of ileal CD patients, but not in the mucosa of the large bowel of colonic CD patients (14), perhaps indicating that granulomatous CD patients were more common in the ileal CD group of their cohort than in the group with colonic disease. Interestingly, a decrease in Roseburia was recently found in the colonic mucosa of young adult mice sensitive to experimental colitis secondary to maternal dietary modification (41), and in patients with ulcerative colitis as well (42).

A decrease in Ruminococcus (supplementary Tables 4, 6, 12, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A119) was detected in our granulomatous CD patients, which was also correlated with the severity of mucosal inflammation (supplementary Fig 6, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A117). Similar results were obtained from the colonic mucosa of adults (43), but not controlled for therapy, granulomas, or inflammation. Perhaps this may be the reason for the discordance between our results and this later manuscript in respect to Eubacterium, where we found a CD associated decrease (supplementary Table 3, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A118) as opposed to Verma and colleagues (43).

Although we could associate granulomatous CD with the decreased presence of Dialister, and increased detection of Porphyromonas and Malassezia, none of these bacterial and fungal taxa were exclusive for differentiating this CD phenotype when examined in all the samples. Malassezia can induce granulomatous inflammation (44), and at least 1 case has been reported of Malassezia furfur sepsis in a patient with CD (45). However, when geographical bias was considered, the association of Malassezia with granulomatous CD was less prominent. In the meantime, Dialister separated all granulomatous samples with being less abundant than in non-granulomatous CD from the Baylor cohort, which pertained to Dialister invisus specifically as well. A decrease in Dialister invisus has been observed in stool from patients with CD and their relatives, supporting our findings (46).

Our results underscore that the presence of giant cells or granulomas in CD are important associates of microbiota composition and should be incorporated into future work in the metagenomics of this disorder.

The finding of CRP levels >1mg/dl correlating with granulomatous CD and microbiota separation in treatment naïve patients is also novel and important for indicating this molecule as a potential biomarker for host-microbial interactions in this disease group. Previous investigations did not reveal association between granulomatous CD and CRP (10), but it is unclear whether this was selectively examined in treatment naive patients, and a cutoff point of significance was not established.

This study includes the first high-throughput microbiota analysis of treatment naive CD incorporating bacterial and fungal metagenomics on colonic mucosal specimens. Therefore, it can be considered as pilot study for future, larger-scale, high-throughput metagenomic investigations in treatment naïve intestinal samples from IBD patients. Our findings support that stringent, geographic/center, clinical, molecular, and histologic selection of patients can further our understanding of dysbiosis in IBD and the relationship between the microbiota and immune responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: R.K. was supported in part by the Broad Medical Research Program, the Broad Foundation (IBD-0252); the Child Health Research Career Development Agency of the Baylor College of Medicine (NIH # 5K12 HD041648); and a Public Health Service grant DK56338, funding the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center, which supported the Baylor biorepository as well. The biorepository of MassGeneral Hospital was supported by The Pediatric IBD Foundation and H.W. was supported in part by philanthropic support from Martin Schlaff.

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for participating in the study, and Antone R. Opekun for his assistance.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- bTEFAP

bacterial tag-encoded FLX amplicon pyrosequencing

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CRP

c-reactive protein

- IBD

inflammatory bowel diseases

- dbRDA

distance based redundancy analysis

- MAP

Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis

- OR

odds ratio

- PCoA

principal coordinates analysis

- RDP

Ribosomal Database Project

- SSU

small subunit

- UC

ulcerative colitis

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jpgn.org).

Data access: Microbial sequences were uploaded to the EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database under the accession number: SRA048320.1

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: RK, SED, HSW ; acquisition of data: RK, SAVM, DN,JLK, YS, SR, JB, HSW; analysis and interpretation of data: RK, SAVM, SBC, SED JLK, YS; drafting of the manuscript: RK, SAVM, DN; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: RK, SBC, HSW; statistical analysis: SBC, SED; obtained funding: RK, HSW; material support: JB, technical support: SR.

References

- 1.Loftus EV., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing Incidence and Prevalence of the Inflammatory Bowel Diseases with Time, Based on Systematic Review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. e42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braegger CP, Ballabeni P, Rogler D, et al. Epidemiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Is There a Shift Towards Onset at a Younger Age? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:141–144. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318218be35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis JD. The utility of biomarkers in the diagnosis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1817–1826. e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solem CA, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al. Correlation of C-reactive protein with clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and radiographic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:707–12. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000173271.18319.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, et al. C-reactive protein: a predictive factor and marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Results from a prospective population-based study. Gut. 2008;57:1518–23. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.146357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurgens M, Mahachie John JM, Cleynen I, et al. Levels of C-reactive protein are associated with response to infliximab therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:421–7. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelsen J, Baldassano RN. Inflammatory bowel disease: the difference between children and adults. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14 (Suppl 2):S9–11. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, et al. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1114–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Matos V, Russo PA, Cohen AB, et al. Frequency and clinical correlations of granulomas in children with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:392–8. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812e95e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan P, Kelly RG, Lee G, et al. Bacterial DNA within granulomas of patients with Crohn’s disease--detection by laser capture microdissection and PCR. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1539–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toracchio S, El-Zimaity HM, Urmacher C, et al. Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis and Crohn’s disease granulomas. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1108–11. doi: 10.1080/00365520802116455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank DN, Robertson CE, Hamm CM, et al. Disease phenotype and genotype are associated with shifts in intestinal-associated microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:179–84. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willing BP, Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, et al. A pyrosequencing study intwins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1844–1854. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehman A, Sina C, Gavrilova O, et al. Nod2 is essential for temporal development of intestinal microbial communities. Gut. 2011;60:1354–62. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.216259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, et al. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swidsinski A, Ladhoff A, Pernthaler A, et al. Mucosal flora in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:44–54. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagalingam NA, Lynch SV. Role of the microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(5):968–84. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lepage P, Hasler R, Spehlmann ME, et al. Twin study indicates loss of interaction between microbiota and mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:227–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conte MP, Schippa S, Zamboni I, et al. Gut-associated bacterial microbiota in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2006;55:1760–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.078824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poulain D, Sendid B, Standaert-Vitse A, et al. Yeasts: neglected pathogens. Dig Dis. 2009;27 (Suppl 1):104–10. doi: 10.1159/000268129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Momozawa Y, Deffontaine V, Louis E, et al. Characterization of bacteria in biopsies of colon and stools by high throughput sequencing of the V2 region of bacterial 16S rRNA gene in human. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey MT, Walton JC, Dowd SE, et al. Photoperiod modulates gut bacteria composition in male Siberian hamsters (Phodopus sungorus) Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:577–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dowd SE, Zaragoza J, Rodriguez JR, et al. Windows.NET Network Distributed Basic Local Alignment Search Toolkit (W.ND-BLAST) BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills DK, Entry JA, Voss JD, et al. An assessment of the hypervariable domains of the 16S rRNA genes for their value in determining microbial community diversity: the paradox of traditional ecological indices. FEMSMicrobiol Ecol. 2006;57:496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowd SE, Delton Hanson J, Rees E, et al. Survey of fungi and yeast in polymicrobial infections in chronic wounds. J Wound Care. 2011;20:40–7. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2011.20.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fallani M, Young D, Scott J, et al. Intestinal microbiota of 6-week-old infants across Europe: geographic influence beyond delivery mode, breast-feeding, and antibiotics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:77–84. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d1b11e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrell L, Wang Y, Antonopoulos D, et al. Standard colonic lavage alters the natural state of mucosal-associated microbiota in the human colon. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Standaert-Vitse A, Sendid B, Joossens M, et al. Candida albicans colonization and ASCA in familial Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1745–53. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young VB, Kahn SA, Schmidt TM, et al. Studying the Enteric Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Getting through the Growing Pains and Moving Forward. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:144. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sartor RB. Key questions to guide a better understanding of host-commensal microbiota interactions in intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:127–32. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagy-Szakal D, Kellermayer R. The remarkable capacity for gut microbial and host interactions. Gut Microbes. 2011;2:178–82. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.3.16107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saulnier DM, Riehle K, Mistretta TA, et al. Gastrointestinal microbiome signatures of pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1782–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, et al. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13780–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobhani I, Tap J, Roudot-Thoraval F, et al. Microbial dysbiosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molnar T, Tiszlavicz L, Gyulai C, et al. Clinical significance of granuloma in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3118–21. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubio CA, Orrego A, Nesi G, et al. Frequency of epithelioid granulomas in colonoscopic biopsy specimens from paediatric and adult patients with Crohn’s colitis. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1268–72. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.045336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pierik M, De Hertogh G, Vermeire S, et al. Epithelioid granulomas, pattern recognition receptors, and phenotypes of Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2005;54:223–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee A, Griffiths TA, Parab RS, et al. Association of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis with Crohn Disease in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:170–4. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181ef37ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaible TD, Harris RA, Dowd SE, et al. Maternal methyl-donor supplementation induces prolonged murine offspring colitis susceptibility in association with mucosal epigenetic and microbiomic changes. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1687–96. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vermeiren J, Van den Abbeele P, Laukens D, et al. Decreased colonization of fecal Clostridium coccoides/Eubacterium rectale species from ulcerative colitis patients in an in vitro dynamicgut model with mucin environment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;79(3):685–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verma R, Verma AK, Ahuja V, et al. Real-time analysis of mucosal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4279–82. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01360-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desai HB, Perkins PL, Procop GW. Granulomatous dermatitis due to Malassezia sympodialis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1085–7. doi: 10.5858/2010-0588-CRR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhargava P, Longhi LP. Images in clinical medicine. Peripheral smear with Malassezia furfur. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:e25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm063672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joossens M, Huys G, Cnockaert M, et al. Dysbiosis of the faecal microbiota in patients with Crohn’s disease and their unaffected relatives. Gut. 2011;60:631–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.223263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.