Abstract

The goal of the current study was to examine the moderating role of in-group social identity on relations between youth exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior in the community and aggressive behaviors. Participants included 770 mother-child dyads living in interfaced neighborhoods of Belfast. Youth answered questions about aggressive and delinquent behaviors as well as the extent to which they targeted their behaviors toward members of the other group. Structural equation modeling results show that youth exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior is linked with increases in both general and sectarian aggression and delinquency over one year. Reflecting the positive and negative effects of social identity, in-group social identity moderated this link, strengthening the relationship between exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior in the community and aggression and delinquency towards the out-group. However, social identity weakened the effect for exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior in the community on general aggressive behaviors. Gender differences also emerged; the relation between exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior and sectarian aggression was stronger for boys. The results have implications for understanding the complex role of social identity in inter-group relations for youth in post-accord societies.

Keywords: social identity, political violence, Northern Ireland, aggression, delinquency

Among the many topics of interest to researchers, clinicians, and policymakers concerned with political violence, is the question of whether violent societies produce aggressive and delinquent youth. Across multiple contexts including the United States, Croatia, and Israel and Palestine there is evidence that youth exposed to violence are at a great risk for a range of negative behaviors including aggression, and delinquent behaviors, such as stealing, carrying a weapon, and destroying property (Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Jacques-Tiura & Baltes, 2009; Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Kerestes, 2006; Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998; Qouta, Punämaki, Miller, & El-Sarraj, 2008). The development of aggressive and delinquent tendencies stem from a range of individual and environmental factors including parent expressions of and responses to conflict (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2004; Patterson, Dishion, & Bank, 1988), cultural mores regarding the use of aggression (Henry et al, 2000; Nipedal, Nesdale, & Killen, 2010), genetics (Caspi et al., 2002), and physiological and biological markers of reactivity (Gordis, Granger, Susman, & Trickett, 2006), among other factors.

There is no simple relationship between violence exposure and youth outcomes, thus, researchers must identify culturally-relevant factors that may increase or decrease the likelihood that growing up in a violent society will result in the development of aggression, delinquency, or the perpetration of violence. Understanding these relationships has implications for individual and community well-being, and in contexts of political violence, findings may have implications for understanding the role that youth play in perpetuating intergroup conflict. In some cases, the history or presence of ethno-political conflict provides an additional motivation for youth to participate in sectarian aggressive and delinquent acts targeted at “the other.”

Social psychological processes are especially important to consider in communities where histories of group dynamics are an integral component of everyday life (Bar-Tal, 2007). In particular, strength of in-group social identity affects intergroup processes such as prejudice and discrimination (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Cairns, 1996). In the face of intergroup threat, strongly identifying with an in-group can accentuate negative responses to that threat, increasing the likelihood of prejudiced attitudes, and in some instances, the endorsement of aggressive behavioral responses (Fisher, Haslam, & Smith, 2010; Struch & Schwartz, 1989), the destruction of property, or other behaviors that make a symbolic statement directed at the entire out-group (Barber, 2009).

At the same time, having strong affiliations with an in-group does not automatically mean one will dislike or even show negative attitudes or behaviors towards out- group members (Brewer, 1999). In other words, in-group love does not equate to out-group hate. As Brewer notes, “Indeed in-group love can be compatible with a range of attitudes toward corresponding out-groups, including mild positivity, indifference, disdain, or hatred” (p. 430). Strongly identifying with an in-group provides individuals with a host of potential resources that can promote positive well-being (Haslam, Jetten, Postmes, & Haslam, 2009) and positive behaviors towards others such as the use of social support and helping behaviors (Haslam & Reicher, 2006; Sabatier, 2008). Identifying with an in-group and interpreting experiences of intergroup threat within a collective identity may encourage individuals to work within the group towards positive social change (Hammack, 2010). The current paper will interrogate these paradoxical roles of social identity, described by Hammack (2010) as the burden and benefit of social identity, by examining how social identity promotes or mitigates the use of aggressive and delinquent behaviors in the face of inter-group threat. Specifically, we will examine the role of youth social identity as a moderator of the relationship between exposure to sectarian threat, and aggressive and delinquent behaviors. We will also examine these relations as they relate to youth expression of sectarian behaviors (i.e., aggressive and delinquent acts directed at out-group members) in post-accord Belfast.

Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987), postulate the interplay between the social context and an individual’s psychological needs that motivate the development of in-group and out-group attitudes and behaviors. More specifically, individuals derive self-esteem from groups with which they identify and the drive to maintain this self-esteem directs attitudes and behaviors towards others. Individuals who identify with the in-group are more likely to view out-group members as more dissimilar compared to in-group members, and they are also more likely to form negative attitudes about out-group members (Bizman & Yinon, 2001; Branscombe & Wann, 1994). Using the minimal group paradigm, a large body of empirical studies has demonstrated that merely placing individuals into groups based on insignificant characteristics is sufficient to create these group-based differences in attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Brewer, 1979; Cadinu & Rothbart, 1996; DiDonato, Ullrich & Krueger, 2011; Eurich-Fulcer & Schofield, 1995; Struch & Schwartz, 1989). It is expected that the relations between intergroup dynamics and intergroup attitudes and behaviors will be more pronounced in areas of conflict where ethno-political identities are highly salient and reminders about group differences and competition are marked on street corners and discussed in the daily news.

Tests of the social psychological processes coming out of social identity theory have recently included youth. Nesdale and colleagues have conducted multiple laboratory based studies showing that in-group norms and out-group threat interact to increase negative intergroup attitudes and intentions to aggress (e.g., Duffy & Nesdale, 2010; Nesdale & Flesser, 2001). For example, Nesdale, Maass, Durkin, and Griffiths (2005) found that children showed more prejudiced attitudes when the in-group had a norm of exclusion and when they were threatened by the out-group. Both factors were directly related to prejudice, and prejudice was highest when both the norm of exclusion and out-group threat were present. Extending this work to understand children’s intentions to aggress, Nesdale, Miliner, Duffy and Griffiths (2009) found that a simulated group competition induced aggressive intentions towards the out-group. In contexts of protracted political violence such as Belfast, where group identities are highly salient, and where exclusion is a norm expressed through segregated living, we expect that the links between social identity and threat are strong, potentially resulting in an increased risk for youth to act out against members of the other group.

Although it is hypothesized that in-group identity strengthens links between intergroup threat and negative attitudes and behaviors toward the out-group, correlates of social identity such as political activity and ideological commitment to in-group goals have also been examined as buffering mechanisms for adults and youth. Political activity and ideological commitment to in-group goals may serve to reduce the negative effects of conflict on mental health (Cairns, 1996; Punamäki, 1996; Punamäki & Suleiman, 1990). Connection to the in-group and commitment to group goals provide individuals with a number of resources including social support, a source of meaning, and a collective psychological motivation for social change (Barber, 2009; Hammack, 2010; Haslam & Reicher, 2006;Wexler, DiFluvio, & Burke, 2009).

Particularly in the face of threat, strength of social identity as an indicator of group affiliation may provide youth with a framework to understand their personal experiences of political and ethnic conflict. The narrative of collective experience shared by a particular group may provide meaning, group resources, and a broader purpose for social change (Wexler et al, 2009; Slone, 2009). Comparing the experiences of Palestinian youth during the first Intifada and Bosnian youth during the war that broke up the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Barber (2008) found that the narrative of the struggle that was passed down to Palestinian youth provided a pre-existing system within which they were able to construct and reconstruct their experiences and identities, providing them with meaning and purpose within the Palestinian struggle. This was counter to the experiences of the Bosnian youth who reported shock and powerlessness in response to the onset of violence. The ability to make sense of their experiences may have contributed to the differences in mental health outcomes seen between the Palestinian and Bosnian youth (Barber, 2008; McCouch, 2008). Slone (2009) also found differences in responses between Palestinian and Israeli youth suggesting that the narrative of the struggle and hope for Palestinian autonomy may protect these youth from the psychological distress of violence political events.

Social identity may also work to bring individuals together to work towards positive social change (Hammack, 2010; Haslam & Reicher, 2006). The idea is that when groups experience threat and their options as individuals to leave that group are limited or non-existent, their most viable option is to pull together as a group and work towards furthering the goals and status of the in-group (Haslam, 2001; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Thus, to the extent that social identity improves mental health and well-being and promotes a move towards positive social change, social identity may be considered a buffering mechanism for youth in contexts of political conflict. Both of these benefits may contribute to more positive in-group interactions, thus decreasing aggression and violence.

To explore further the role of youth social identity in relation to political violence and aggression and delinquency, the current study utilized survey data from a large sample of youth living in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Data were drawn from a longitudinal study designed to examine the multiple processes and risk and protective factors that affect youth development in contexts of political violence (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, Schermerhorn, Merrilees & Cairns, 2009).

The ongoing conflict between groups in Northern Ireland is rooted in issues of nationality and the constitutional position of Northern Ireland (Cairns & Darby, 1998; McGrellis, 2005). On one side are the Unionists (Protestants) wanting Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom, whilst the Nationalists (Catholics) are seeking Irish unification and the removal of Northern Ireland’s constitutional place within the United Kingdom. Although the conflict dates back several centuries, contemporary studies of the conflict typically focus on the 30-year period (1968-1998) of violence known as the Troubles. This period was characterized by frequent, violent, armed confrontations between various combinations of State forces, illegal paramilitary groups, and civilians. Since the Troubles began, more than 3,600 people have been killed, around 20,000-30,000 imprisoned, and some 50,000 reported as injured (Cairns & Darby, 1998; Cairns, Wilson, Gallagher, & Trew, 1995; McEvoy & Shirlow, 2009). The Belfast Agreement, signed in 1998, led to the creation of a power-sharing administration between the political parties representing these groups (Unionists and Nationalist/Republicans). Both sectarian and nonsectarian community antisocial behaviors remain significant issues, especially for people living in the interfaced areas of Belfast (McGrellis, 2005). Interfaced areas are defined as adjacent communities (one Catholic, one Protestant) living along a disputed territorial border that is usually defined by security walls and other physical constructs that aim to reduce contact between such communities (Shirlow and Murtagh, 2006). Within Belfast, less that 23% of Catholics and 17% of Protestants live in what are interpreted as shared neighborhoods (Shirlow and Murtagh, 2006). Thus, despite the signing of the peace agreement, Northern Ireland, and the interfaced communities of Belfast in particular, continue to be plagued by inter-group tension (MacGinty, Muldoon, & Ferguson, 2007).

In Belfast, where a majority of youth live in segregated spaces and attend segregated schools (Campbell, Cairns, & Mallett, 2004) norms of exclusion are experienced in daily life, and the threat of sectarian violence and antisocial behaviors persist (MacGinty et al., 2007). These contextual risks motivated two goals for the current study. The first goal was to examine the relation between exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior and adolescents’ aggressive and delinquent behaviors. In addition to answering standard questions about aggressive and delinquent behaviors, adolescents were asked how often they were likely to commit aggressive and delinquent acts directed at members of the out-group. This allowed us to distinguish between how exposure to sectarian threat relates to general aggression or delinquency, and to aggressive and delinquent acts directed specifically at the out-group.

The second goal was to examine the role of adolescent social identity as a moderating factor in the relation between out-group threat and aggression and delinquency. Examining moderation allows us to examine how the co-occurrence of sectarian threat and social identity predict aggression against the out-group and general aggression. This approach assumes that adolescents experience the threat posed by the other group through the lens of their current strength of social identity. It was expected that higher levels of social identity would strengthen the relation between exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior and aggression against the out-group. Drawing from the literature suggesting individual and group benefits of social identity, youth strength of social identity was also examined as a moderator of the link between sectarian threat and overall aggressive and delinquent behaviors and delinquency.

For several reasons, gender differences in the links among these factors are also examined. First, boys are more likely than girls to commit aggressive and delinquent behaviors (Moffit, Caspi, Rutter, & Silva, 2001) and the gap in frequency of these behaviors between males and females increases through late adolescence (Hicks et al., 2007). Boys have also reported more experience with political violence (Muldoon, 2004). Using interview data with young children, Connolly, Smith, and Kelly (2002) found that boys were more likely to identify with a community and make sectarian comments. Relevant to the observed benefits of social identity and the stress and coping process (Punamäki, 1996; Punamäki & Suleiman, 1990), research suggests that negative affect, such as anger, due to stress is more likely to result in aggression for males compared to females (Sadeh, Javdani, Finy, & Verona, 2011). Research has also shown that when anger is the emotional response to intergroup threat, an individual is more likely to respond in a hostile way against the out-group (Mackie, Devos, & Smith, 2000). Thus, it is expected that both relations between intergroup threat and aggression and delinquency against the out-group, and the moderating role of social identity on behaviors against the out-group will be stronger for boys.

Method

Participants

Participants for the current study included 770 mother-child dyads from the 3rd (Time 1) and 4th (Time 2) waves of the ongoing study on the impact of political violence on families in Belfast. The sample was equally divided by gender (boys=378, girls=392). In the current analyses, the average age of adolescents at Time 1 was 13.58 years old (SD = 1.98, range 8 to 19), and the average age at Time 2 was 14.63 years old (SD = 1.96, range 9 to 19). Mothers’ mean age was 38.59 (SD=6.18; range: 27-62). Thirty-eight percent (n= 292) of mothers were married or living as married; 19% were separated or divorced (n=148); 2% were widowed (n=17); and 38% (n=289) were never married.

Of the 770 families at Time 1, 82% returned at Time 2 (N=631). There were only two significant differences between the full sample at Time 1 and those families that did not participate at Time 2. First, Protestants were less likely to participate at Time 2 (χ2 (2) =10.84, p=.004). The sample was 62% Protestant and 38% Catholic at Time 1 and 60% Protestant and 40% Catholic at Time 2. The ethnic composition of the sample at Time 1 and Time 2 approximates the overall population of Northern Ireland (57% Protestant, 43% Catholic; Darby, 2001). Second, mothers who rated their children as having more conduct problems were less likely to return at Time 2 (t=5.55, p<.001). There were no other group differences between the two time points for any of the other study variables: sectarian antisocial behavior, aggression, sectarian aggression, delinquency, social identity, gender, or age. Finally, consistent with the demographics of Northern Ireland, all study participants were White.

Neighborhoods

Given that the majority of politically-motivated crime occurs within segregated communities, along interface lines and in areas with high social deprivation (Mesev, Shirlow, & Downs, 2009), families were recruited from areas in Belfast with this profile. Study areas were relatively similar in terms of socio-economic status. In Northern Ireland, all 582 wards are indexed based on a social deprivation measure. The ranking is determined by income, employment, health, education, proximity to services, crime, and the quality of the living environment. All of the study wards were in the worst fifth and over 75% were in the worst tenth of the most-deprived wards in Northern Ireland (NISRA, 2010).

Procedures

In the targeted neighborhoods, families were selected using stratified random sampling to achieve a gender balance; eligible families had to have a child living in the home initially between the ages of 10 and 17 years old. In this developmental stage, children and adolescents are aware of Catholic/Protestant differences and more likely to be exposed to, or victims and perpetrators of, sectarian antisocial behavior (Cairns, 1987). In addition, the majority of the children in the study were born after the signing of the peace agreement.

The study was conducted under the approval and direction of the Institutional Review Board at all participating universities. Mothers and children provided consent and assent, respectively, before participating and all questionnaires were administered as interviews in the participant’s home by professionals from an established market research firm in Northern Ireland. Interviews were conducted in separate rooms to ensure privacy and lasted approximately one hour; families received a modest financial compensation for their participation.

Measures

Exposure to Sectarian Antisocial Behavior (SAB)

The SAB scale was developed in a culturally-informed manner through focus groups and a two-wave pilot test in Northern Ireland (Goeke-Morey et al., 2009). In the current study, youth were asked to report on their exposure to and knowledge of sectarian antisocial behavior (SAB) in the community over the past three months. The scale of 12 items included politically-motivated events such as name calling by people from the other community, stones or objects thrown over walls and deaths or serious injury caused by the other community. Participants indicated the frequency of SAB using a 5-point Likert scale from 0 = “not in the last 3 months” to 4 = “every day” with a possible range from 0 to 48. Higher scores represent more experiences with sectarian antisocial behavior in the three months prior to data collection. For the current analyses, a manifest variable was constructed using a composite measure: all 12 SAB items at Time 2 were summed for each child. The internal consistency of the scale was good (Cronbach’s α = .94).

Social Identity

Youth reported on their level of attachment to, or strength of their Catholic/Protestant social identity (Brown, Condor, Mathews, Wade, & Williams, 1986) at time 2. This measure has been used in numerous studies in Northern Ireland (Cairns, Kenworthy, Campbell, & Hewstone, 2006; Merrilees et al., 2011). After stating which community he/she belonged to, adolescents were asked 5 items such as if they are a person who identifies with the (insert Catholic or Protestant) community and a person who feels strong ties with the (insert Catholic or Protestant) community. Participants responded to questions on a 5-point Likert scale from 1= “never” to 5 = “very often.” Total scores ranged from 5 to 25; higher scores indicated stronger social identity, or in-group identification. Youth scores were added for a composite manifest variable of social identity. The internal consistency of social identity was strong (Cronbach’s α = .95).

Aggression

The aggression and anger scale measured overt and direct acts of physical and psychological aggression for individuals in early adolescence (Orpinas & Frankowsi, 2001). The 11-item scale includes two dimensions: Physical and Verbal Aggression, and Anger, the emotional state that leads to aggressive acts. Youth report on the numbers of times they have done or experienced statements such as I fought back when someone hit me first, I encouraged other students to fight and I got into a physical fight because I was angry in the last seven days to reduce recall bias. Possible answers range from 0 = “none” to 6 = “more than 6” on a 7-point Likert scale with a total summed score of 0 to 66. The scale has content validity with teachers and experts on youth aggression. In the original sample, construct validity was confirmed through correlations with teachers’ ratings of aggression and the number of fights at school, number of injuries due to fights, and the number of days the student carried a weapon to school. The scale has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ranged from .86 to .88) and the test-retest coefficient was .63 one year later (Orpinas & Frankowsi, 2001). These consistency ratings do not vary by gender, ethnicity or grade. In the current study, a composite of the 11 items was summed and entered as one manifest variable for a latent variable representing aggressive and delinquent behaviors.

Delinquency

Delinquent acts were reported with 14 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (McCrystal, Higgins & Percy, 2006). This measure was developed for use with adolescents in Northern Ireland as part of a longitudinal study of adjustment (McAloney, McCrystal, Percy, & McCartan, 2009). Sample items included stolen or ridden in a stolen car, van or motorbike, deliberately damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you, and written things or sprayed paint on property that did not belong to you. Recognizing the lower base rate of delinquent acts compared to aggressive acts and feelings, responses for this scale measured the frequency of engaging in these behaviors over the past 12 months. Responses ranged from 0 = “never” to 5 = “10 or more times” with a total possible score of 56.

Conduct Problem

Conduct problems were measured using the 5-item subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) completed by the mothers. A sample item from the conduct subscale is My child fights a lot. My child makes other people do what he/she wants; mothers reported how much these items were typical of their child over the past six months on a 3-point Likert scale 0 = “not true,” 1 = “somewhat true,” and 2 = “certainly true.” Composite scores for the conduct problems subscale were entered as a manifest predictor for the latent variable of aggressive and delinquent behaviors. Cronbach’s α for the two time points were .70 and .51, respectively.

Sectarian Aggression and Delinquency

The frequency with which youth committed aggressive and delinquent acts that were directed at the out-group was assessed. After responding to the 11-item aggression and anger scale and the 14-item delinquent acts scale, youth were asked: “Thinking about all these things, how often did you do them toward people or things from the other community?” Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 = “never” to 4 = “very often.” Higher scores were a sign that the adolescent committed antisocial behaviors to ‘get at’ the other community more often. The latent variable of sectarian acts was constructed using the responses to these two single-item questions as manifest indicators and the two outcome variables were allowed to correlate, accounting for the overlap between the two constructs.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

The means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for all manifest variables are included in Table 1. Independent t-tests were conducted to examine gender differences in all study variables. The results of these tests show that boys reported more exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior (t (549) = 3.46, p = .001), more aggressive behaviors (time 1: t (767) = 3.55, p < .001; time 2: t (614) = 3.27, p < .001), and more delinquent behaviors (time 1: t (763) = 2.64, p = .009). In terms of sectarian behaviors, boys also reported more aggressive (1: t (749) = 3.60, p < .001) and delinquent behaviors (1: t (719) = 2.48, p = .013) directed at the other group. Mothers also reported more conduct problems for boys compared to girls (time 1: t (767) = 1.81, p = .071; time 2: t (612) = 3.79, p < .001). There was no significant difference in youth reports of social identity.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations for all manifest variables and factors.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SAB | 2.93 | 6.91 | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Social Identity | 18.85 | 5.34 | -.04 | - | |||||||||

| 3. SDQ conduct Time 1 | 2.56 | 2.24 | .15*** | -.05 | - | ||||||||

| 4. SDQ conduct Time 2 | 2.08 | 1.72 | .26*** | -.06 | .49*** | - | |||||||

| 5. Aggression Time 1 | 3.82 | 7.51 | .32*** | -.10* | .24*** | .35*** | - | ||||||

| 6. Aggression Time 2 | 2.41 | 5.56 | .42*** | -.10* | .21*** | .31*** | .68*** | - | |||||

| 7. Delinquency Time 1 | 1.33 | 4.16 | .24*** | -.06 | .19*** | .25*** | .59*** | .44*** | - | ||||

| 8. Delinquency Time 2 | .91 | 3.60 | .39*** | -.08 | .17*** | .23*** | .35*** | .61*** | .64*** | - | |||

| 9. Sectarian Aggression Time 1 | .30 | .64 | .14** | -.05 | .05 | .13** | .33*** | .23*** | .37*** | .15*** | - | ||

| 10. Sectarian Aggression Time 2 | .38 | .71 | .16*** | -.01 | .06 | .13** | .13** | .20*** | .17*** | .21*** | .37*** | - | |

| 11. Sectarian Delinquency Time 1 | .18 | .52 | .15** | -.03 | .03 | .10* | .19*** | .21*** | .35*** | .20*** | .55*** | .37*** | - |

| 12. Sectarian Delinquency Time 2 | .28 | .65 | .18*** | -.04 | .01 | .09* | .06 | .13** | .14** | .197** | .32*** | .54*** | .37*** |

Note:

Correlation significant at p<.05 (2-tailed) and

p<.001 (2-tailed).

Model Test

Pertinent to the main hypotheses, structural equation modeling was used to test the model seen in Figure 1. Structural equation modeling (SEM) provides several advantages over traditional multiple regression approaches (Dunn, Everitt & Pickles, 1993). SEM allows for the creation of latent variables which decreases the bias due to measurement error as shared variance and measurement error are estimated, providing a more reliable measure of the latent construct. Additional advantages are the ability to evaluate the fit of the proposed model as a whole and the ability to compare models based on model fit indices. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used, which adequately estimates parameters with missing data under the assumption that the data is missing at random.

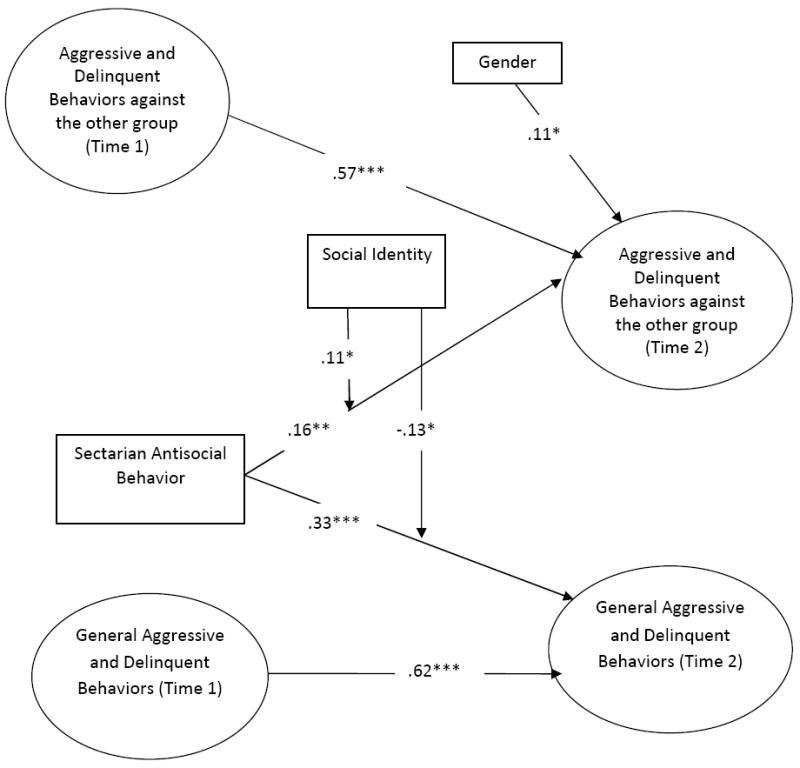

Figure 1.

Structural equation modeling results for the relations between sectarian antisocial behavior, social identity and youth aggressive and delinquent behaviors. Note: The main effect for social identity was also estimated predicting both the latent variable for general aggression and delinquency and the latent variable for aggression and delinquency toward the out-group. Both paths were non-significant. Gender was estimated as a predictor of both outcome variables but only significantly predicted sectarian behaviors. Correlations between gender and all exogenous variables were also estimated but not included in the model for the sake of readability.

Several indices of model fit are reported: the relative χ2 index (χ2/df); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the normative fit index, and the comparative fit index (NFI, CFI; Bentler, 1990). Acceptable model fit is suggested by scores below 3 on the χ2/df index (Bollen, 1989), values above .90 for the CFI and NFI (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and RMSEA values below .08.

The measurement model was first tested to support use of the latent variables. A confirmatory factor model with the four latent variables (aggressive and delinquent behaviors Time 1 and Time 2, and aggression and delinquency towards the out-group at Time 1 and Time 2) was constructed. All factors were allowed to correlate and error terms for the same scale or item were allowed to correlate over time. The results of this model test suggest that the model fit the data (χ2 (54)= 185.18; χ2/df =3.43; CFI = .95; NFI = .93; RMSEA = .049 (90%CI (.041-.057).

To test for the moderating role of social identity on aggression, SAB, social identity, and the interaction term were modeled as manifest variables. SAB and social identity were both centered. The centered predictors and the product of the centered variables were included in the model (Aiken & West, 1991).

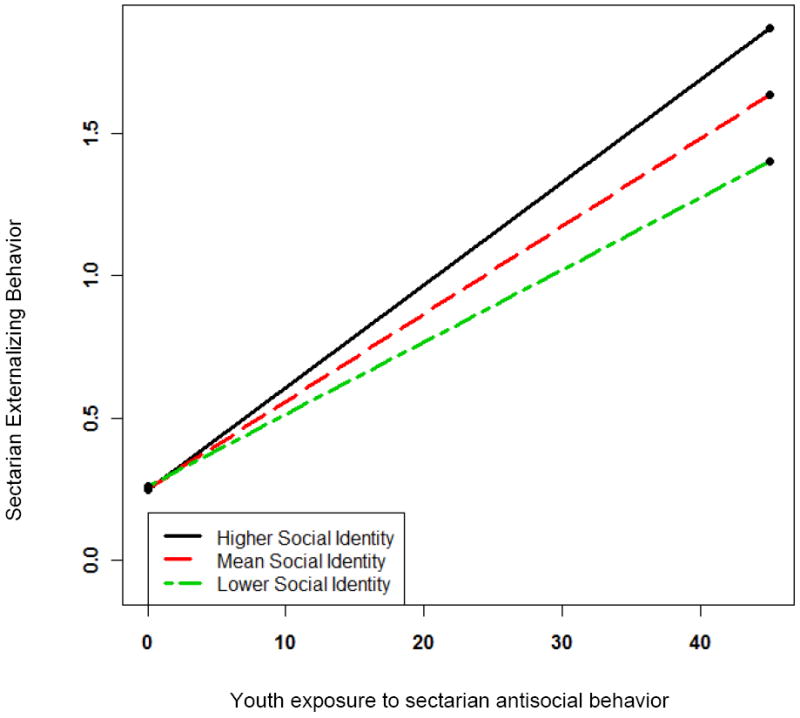

Tests of the main model suggest that the model fits the data well (See Figure 1). Unstandardized and standardized regression paths for the model are included in Table 2. Both outcome variables tested were stable between Time 1 and Time 2 (Sectarian Acts: β = .57, p < .001; General behaviors: β = .62, p < .001). Controlling for sectarian acts one year earlier, exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior (SAB) over the previous three months was related to more aggressive and delinquent behaviors directed at the out-group (β = .16, p = .001). This relationship was stronger for youth reporting higher levels of social identity (β = .11, p = .03). Exposure to SAB was also related to higher levels of general aggressive and delinquent behaviors (β = .33, p < .001); however, for youth reporting higher levels of social identity, the strength of the relationship between SAB and general aggressive behaviors was weaker (β = -.13, p <.001). A graphical depiction of the interaction for predicting sectarian behaviors can be seen in Figure 2. Consistent with suggestions for graphing continuous interactions (Aiken & West, 1991), the relations between the predictor (SAB) and the outcome (aggression and delinquency directed at the out-group) were graphed for the mean level of the moderator (social identity), and one standard deviation above (high social identity) and below (low social identity) the mean.

Table 2.

Results of main model testing the moderating effect of youth social identity on the relations between exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior and aggressive and delinquent behaviors

| General Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors | Sectarian Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| b | S.E. | β | b | S.E. | β | |

|

|

||||||

| Gender | -.06 | .23 | -.01 | .12 | .05 | .11* |

| Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors Time 1 | .50 | .03 | .63*** | - | - | - |

| Sectarian Aggressive and Delinquent | - | - | - | .64 | .07 | .57*** |

| Behaviors Time1 | ||||||

| SAB | .19 | .02 | .33*** | .012 | .004 | .16*** |

| Social Identity | -.03 | .03 | -.01 | -.001 | .005 | -.01 |

| SAB × Social Identity | -.013 | .004 | -.13*** | .001 | .001 | .11* |

Note:

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001.

The hash marks indicate that the variable was not included as a predictor of the latent variable representing that outcome.

Figure 2.

The interaction between sectarian antisocial behavior and social identity predicting sectarian behaviors.

Gender Differences

Differences between boys and girls were also explored. Multi-group analysis was attempted in AMOS; however when the model was fitted separately for boys and girls, the model resulted in a non-positive definite matrix potentially indicating model misspecification. To simplify the exploration of these tests gender differences were then examined using moderated multiple regression. To test for the differences in processes for boys and girls the manifest variables of the latent variables were summed. To create the interaction terms, all variables (other than gender) were centered and then multiplied together. This process resulted in eight predictor variables. All terms were entered simultaneously. No significant gender difference emerged in the prediction of general aggressive and delinquent behaviors. The standardized regression coefficients predicting youth behaviors against the out-group can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Tests of the 3-way interaction between Gender, SAB and Social Identity predicting Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors.

| General Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors | Sectarian Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| b | S.E. | β | b | S.E. | β | |

| Gender | -.26 | .55 | -.01 | .12 | .10 | .05 |

| Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors Time 1 | .55 | .03 | .63*** | - | ||

| Time 1 Sectarian Aggressive and Delinquent Behaviors | - | .54 | .05 | .44*** | ||

| SAB | .47 | .12 | .37*** | .07 | .02 | .37*** |

| Social Identity | -.32 | .16 | -.19 | .02 | .03 | .08 |

| SAB × Social Identity | .01 | .02 | -.02 | .02 | .004 | .49*** |

| Gender × SAB | -.14 | .08 | -.16 | -.03 | .02 | -.27* |

| Gender × Social Identity | .17 | .10 | .16 | -.02 | .02 | -.11 |

| Gender × SAB × Social Identity | -.02 | .02 | -.14 | -.01 | .003 | -.43** |

Note:

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001.

The hash marks indicate that the variable was not included as a predictor of the variable representing that outcome.

A significant interaction between SAB and gender was found, with the relationship between SAB and aggressive and delinquent behaviors against the out-group stronger for boys than girls (boys coded as 0 and girls coded as 1: β = -.27, p = .044). A significant three-way interaction suggested a difference between boys and girls in the way that social identity moderated the link between sectarian threat and behaviors against the out-group (β =- .43, p = .001). The moderating role of social identity on the link between SAB and behaviors against the out-group was stronger for boys than girls. This implies that social identity may be acting as a stronger factor for boys compared to girls.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine the impact of youth social identity on the link between exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior and both general and sectarian aggression and delinquency in a community that has experienced protracted political violence. The results demonstrated that youth exposure to sectarian antisocial behavior was related to increases in both general and sectarian aggressive and delinquent behaviors. The results also demonstrated that for youth who identify more strongly with their in-group, threat posed by the other group in the form of sectarian antisocial behavior is more likely to lead to sectarian aggressive and delinquent behaviors, that is, behaviors directed toward the out-group. This finding was consistent with previous work showing that when group identity is salient, youth are more likely to show prejudiced attitudes and behavioral intentions to aggress toward out-group members in the face of intergroup threat (Nesdale et al., 2005; Nesdale et al., 2009; Struch & Schwartz, 1989). Social identity theory would also predict that in the face of intergroup threat, youth who are highly identified with the in-group may be motivated to differentiate from the other group and increase the status of their own group by derogating the other (Branscombe & Wann, 1994). It is also important to note that the main effect for social identity was non-significant for both general aggression and aggression directed at the out-group. This further supports the notion that in-group love does not necessarily result in out-group hate. It is only in the face of intergroup threat that social identity related to aggression against the out-group.

At the same time, social identity decreased the strength of the relationship between sectarian threat and general aggression and delinquency. This multi-faceted role of social identity is consistent with the current conceptualizations of social identity as both a potential risk and protective factor (Hammack, 2010). For some youth, strong identification with the in-group may play a protective role giving meaning to the negative experience of sectarian antisocial behavior thus reducing the likelihood of becoming involved in aggression or anti-social behaviors. There are two potentially overlapping explanations for why we saw a decrease in general aggression for youth with a stronger sense of social identity. It is possible that youth with higher social identity are receiving more social support from in-group members, or that this social support allied with a high level of social identity allows them to make meaning of the threat they experience, both of which could be decreasing the potential for negative emotional responses to intergroup threat. It is also possible that in the face of intergroup threat, youth with higher in-group social identity are motivated to improve relations within their group. Given the overall low frequencies of youth indicating they act out for the sake of getting at out-group members, and that these youth live generally segregated lives, it is safe to assume that most of their aggression and delinquent behaviors are directed at in-group members. Thus, the observed decrease in aggression and delinquency for high identifiers may reflect that some youth are motivated to improve relations within their own group when faced with inter-group threat.

The results also support the hypothesis that social identity would be a stronger motivating factor for boys compared to girls. That is, social identity strengthened the link between sectarian anti-social behavior and aggression and delinquency against the out-group more for boys than girls. Social identity may be more salient for boys (Connolly et al., 2002), and as a result, a stronger influence on the impact of environmental risk on behaviors. This finding is also consistent with previous literature suggesting that boys are both more likely to experience political violence (Muldoon, 2004) and exhibit aggressive behaviors (Moffit et al., 2001). The results do not necessarily indicate that boys are more affected by political violence compared to girls. Rather, the results were consistent with the notion that expressions of emotional experiences are more likely to be directed outward for males as compared to females (Sadeh et al., 2011). These findings suggest that in a setting of protracted conflict, the role of gender should also be considered in the link between political violence and adolescent outcomes.

The current study advances our understanding of the role of intergroup threat and aggressive and delinquent behaviors in a real-world setting of political violence; however, the limitations of the study design should be noted. One important limitation is the survey approach. As with all surveys conducted outside of the laboratory, causation should be interpreted with caution and lurking third variables may be threats to the validity of the findings. At the same time, the two-wave data is an advance from cross-sectional designs and allows for the examination of rank order change, giving more confidence to the direction of relations. An additional limitation is the scope of questions asked regarding the expression of sectarian behaviors. It is possible that young people express hostilities towards the out-group in a variety of ways not captured in the questions used in the current study. The limited scope of this variable may have attenuated findings. Future research should explore how youth express these behaviors and what their goals and motivations are in doing so. For example Leonard (2010) noted that when she talked to Catholic and Protestant young people in Belfast about their apparently casual involvement in rioting she found that “their participation was imbued with political undertones” (Leonard, 2010). Future research should also include examination of internalizing problems such as depression and anxiety, and positive outcomes such as pro-social behaviors.

Future research should also consider the degree to which adolescent expression of aggression and hostility towards out-group members is an expression of political activism. As Dawes’ (1990) observed in South Africa “that where the youthful political activist is highly socialized…..his or her use of violence will be contained within the political struggle” (pg. 37). Evidence to support the idea that sectarian aggression does not spill over into non-sectarian aggression comes from early observations of young people in Northern Ireland charged with “terrorist” (i.e. political; Cairns, 1987) offenses. According to Cairns, there was both anecdotal and empirical evidence indicating that young people charged with political offenses, when compared to their peers charged with “ordinary” crime, were less likely to have an existing criminal record. This would suggest that youth who are aggressing against the out-group may not be the same youth aggressing against in-group members, or aggressing more generally. This further suggests that social identity is operating differently for different youth. Future research should continue to identify when and for whom experiences of intergroup threat and political violence will result in increased use of aggression and delinquency directed at targeted others and when it is expressed more generally.

We also recognize that identity is multidimensional and dynamically changing over time. Recent work examining the components and construction of identity, specifically for youth in contexts of political violence, has shown the richness and complexity of youth identity. For example, there may be important differences in the roles of national and religious identity (Muldoon, McLaughlin, & Trew, 2007). Research drawing from social identity theory has shown that it may act as a mediating or process-level variable changing in the face of intergroup threat (Haslam & Reicher, 2006; Muldoon, Schmid, & Downes, 2009). Examining the extent to which sectarian threat predicts changes in social identity which then predict aggression and other out-group behaviors is an important direction for future research.

The current study has important implications for societies considering implementing programs designed to alter the nature of group identity in hopes of decreasing negative out-group expressions. While the costs or burden associated with group identities is recognized, the benefits must also be recognized and more fully understood (Hammack, 2010). The collective nature of social identity in a setting of political conflict has implications for conflict transformation and peaceful coexistence (Lederach, 2005; Minow, 1998). Political opportunists may take advantage of collective identities to mobilize violent campaigns, for example (Kaufman, 1996). At the same time, social identity may protect low status groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) and individuals from the negative impact of intergroup tension (Merrilees et al., 2011). Finally, a sense of collective identity and shared in-group beliefs may help social groups mobilize for constructive social change (Comas-Díaz, Lykes & Alarcón, 1998; Martín-Baró, 1996; Barber, 2009). Thus, social identity may bring both individual psychological as well as collective and social benefits to youth growing up in post-conflict environments (Hammack, 2010). At the same time the costs associated with positive change in the face of trauma has also been discussed within the literature on posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). Recent studies linking posttraumatic growth to negative outcomes such as PTSD symptoms and out-group bias have further demonstrated the complexity of unfolding psychological outcomes in post-trauma situations (Hobfoll et al., 2007) suggesting the need for more longitudinal work in this area.

The findings from the current study advance understanding of complex youth behaviors in a setting of protracted conflict. Going beyond showing the negative relationship between exposure to violence and aggressive and delinquent behaviors, the current study also highlights how social identity and gender can affect this relationship. Understanding these patterns of risk and resilience has implications for adolescents and for the broader community. Moreover, the identification of which factors contribute to more aggression against the out-group may also have important policy implications for the continuation of intergroup animosity and the possibilities of more positive peace in Northern Ireland.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many families in Northern Ireland who have participated in the project. We would also like to express our appreciation to project staff, graduate students, and undergraduate students at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Ulster.

This research was support by NICHD grant 046933-05 to E. Mark Cummings.

Contributor Information

Christine E. Merrilees, University of Notre Dame

Ed Cairns, University of Ulster.

Laura K. Taylor, University of Notre Dame

Marcie C. Goeke-Morey, The Catholic University of America

Peter Shirlow, Queen’s University, Belfast.

E. Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing andinterpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Contrasting portraits of war: Youth’s varied experiences with political violence in Bosnia and Palestine. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:298–309. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Adolescents and War. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D. Sociopsychological foundations of intractable conflicts. American Behavioral Scientist. 2007;50:1430–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizman A, Yinon Y. Intergroup and interpersonal threats as determinants of prejudice: The moderating role of in-group identification. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2001;23:191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Boothby N, Strang A, Wessells M, editors. A World Turned Upside Down: Social Ecologies of Children and War. Westport, CT: Kumarian Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Wann DL. Collective self-esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1994;24:641–657. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB. In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB. The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love or outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues. 1999;55:429–444. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 136–262. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Condor S, Mathews A, Wade G, Williams J. Explaining intergroup differentiation in an industrial organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 1986;59:273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Cadinu MR, Rothbart M. Self anchoring and differentiation process in the Minimal Group setting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:661–677. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E. Caught in the crossfire: Children and the Northern Ireland conflict. Belfast: Appletree Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E. Children and Political Violence. Blackwell; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E, Darby J. The conflict in Northern Ireland: Causes, consequences and controls. American Psychologist. 1998;53(7):754–760. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E, Kenworthy J, Campbell A, Hewstone M. The role of in-group identification, religious group membership and intergroup conflict in moderating in-group and out-group affect. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2006;45:701–716. doi: 10.1348/014466605x69850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns E, Wilson R, Gallagher T, Trew K. Psychology’s contribution to understanding the conflict in Northern Ireland. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. 1995;1:131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Cairns E, Mallett J. Northern Ireland: The Psychological Impact of “The Troubles”. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma Special Issue: The Trauma of Terrorism: Sharing Knowledge and Shared Care, An International Handbook. 2004;9:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IV, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L, Lykes MB, Alarcón RD. Ethnic conflict and the psychology of liberation in Guatemala, Peru, and Puerto Rico. American Psychologist. 1998;53:778–792. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.7.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly P, Smith A, Kelly B. Too young to notice? The cultural and political awareness of 3-6 year olds in Northern Ireland. 2002 Retrieved from www.paulconnolly.net/publications/report_2002a.htm.

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Schermerhorn AC, Merrilees CE, Cairns E. Children and political violence from a social ecological perspective: Implications from research on children and families in Northern Ireland. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:16–38. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. Everyday marital conflict and child aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:191–202. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019770.13216.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes A. The effects of political violence on children: A consideration of South African and related studies. International Journal of Psychology. 1990;25:13–31. [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato TE, Ullrich J, Krueger JI. Social perceptions as induction and inference: An integrative model of intergroup differentiation, in-group favoritism, and differential accuracy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:66–83. doi: 10.1037/a0021051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Nesdale D. Group norms, intra-group position and children’s aggressive intentions. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2010;7:696–716. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G, Everitt B, Pickles A. Modeling covariances and latent variables using EQS. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eurich-Fulcer R, Schofield JW. Correlated versus uncorrelated social categorizations: The effect on intergroup bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P, Haslam SA, Smith L. “If you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” Social identity salience moderates support for retaliation in response to collective threat. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice. 2010;14:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Baltes BB. Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1227–259. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Ellis K, Merrilees CE, Schermerhorn AC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. The differential impact on children of inter- and intra-community violence in Northern Ireland. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. 2009;15:367–383. doi: 10.1080/10781910903088932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis EB, Granger DA, Susman EJ, Trickett PK. Asymmetry between salivary cortisol and α-amalayse reactivity to stress: relation to aggressive behavior in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan P. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:101–116. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL. Identity as burden or benefit? Youth, historical narrative, and the legacy of political conflict. Human Development. 2010;53:173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SA. Psychology in organizations: The social identity approach. London: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SA, Jetten J, Postmes T, Haslam C. Social identity, health and well-being: An emerging agenda for applied psychology. Journal of Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2009;58:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Haslam SA, Reicher S. Stressing the group: Social identity and the unfolding dynamics of responses to stress. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:1037–1052. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Guerra N, Huesmann R, Tolan P, VanAcker R, Eron L, et al. Normative influences on aggression in urban elementary school classrooms. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:59–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1005142429725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Kramer MD, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McCue M. Gender differences and developmental change in externalizing disorders from late adolescence to early adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:433–447. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Hall BJ, Canetti-Nisim D, Galea S, Johnson RJ, Palmieri PA. Refining our understanding of traumatic growth in the face of terrorism: Moving from meaning cognitions to doing what is meaningful. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2007;56:345–366. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;61:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman C. Possible and impossible solutions to ethnic conflicts. International Security. 1996;20:136–75. [Google Scholar]

- Keresteš G. Children’s aggressive and prosocial behavior in relation to war exposure: Testing the role of perceived parenting and child’s gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lederach JP. The challenge of terror: A travelling essay. Peace and Conflict Studies. 2005;12:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard M. What’s recreational about’ recreational rioting? Children on the streets in Belfast. Children and Society. 2010;24:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Cicchetti D. An ecological-transactional analysis of children and contexts: The longitudinal interplay among child maltreatment, community violence, and children’s symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:235–257. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800159x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie DM, Devos T, Smith ER. Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:602–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGinty R, Muldoon OT, Ferguson N. No War, No Peace: Northern Ireland after the Agreement. Political Psychology. 2007;28:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Baró I. Writings for a Liberation Psychology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McAloney K, McCrystal P, Percy A, McCartan C. Damaged youth: Prevalence of community violence exposure and implications for adolescent well-being in post-conflict Northern Ireland. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:635–648. [Google Scholar]

- McCouch RJ. The effects of wartime violence on young Bosnians’ postwar behaviors: Policy contours for the reconstruction period. In: Barber BK, editor. Adolescents and war: how youth deal with political violence. NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McCrystal P, Higgins K, Percy A. Brief Report: School exclusion drug use and delinquency in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy K, Shirlow P. Reimagining DDR: Ex-combatants, leadership and moral agency in conflict transformation. Theoretical Criminology. 2009;13:31–59. [Google Scholar]

- McGrellis S. Pushing the boundaries in Northern Ireland: young people, violence and sectarianism. Contemporary Politics. 2005;11:53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees CE, Cairns E, Goeke-Morey MC, Schermerhorn AC, Shirlow P, Cummings EM. Associations between mothers’ experience with the Troubles in Northern Ireland and mothers’ and children’s psychological functioning: The moderating role of social identity. Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;39:60–75. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesev V, Shirlow P, Downs J. The Geography of Conflict and Death in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2009;99:893–903. [Google Scholar]

- Minow M. Between Vengeance and Forgiveness. Boston: Beacon Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex differences in antisocial behaviour: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon OT. Children of the Troubles: The Impact of Political Violence in Northern Ireland. Journal of Social Issues Special Issue: The Cost of Conflict: Children and the Northern Irish Troubles. 2004;60:453–468. [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon OT, McLaughlin K, Trew K. Adolescents’ perceptions of national identification and socialization: A grounded analysis. Journal of Peace research. 2008;45:681–695. [Google Scholar]; British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 25:579–594. [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon OT, Schmid K, Downes C. Political violence and psychological well-being: The role of social identity. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2009;58:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D, Flesser D. Social identity and the development of children’s group attitudes. Child Development. 2001;72:506–517. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D, Maass A, Durkin K, Griffiths J. Group Norms, Threat, and Children’s Racial Prejudice. Child Development. 2005;76:652–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D, Milliner E, Duffy A, Griffiths JA. Group membership, group norms, empathy, and young children’s intentions to aggress. Aggressive Behavior. 2009;35:244–258. doi: 10.1002/ab.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nipedal C, Nesdale D, Killen M. Social group norms, school norms, and children’s aggressive intentions. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:195–204. doi: 10.1002/ab.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Frankowski R. The Aggression Scale: A self-report measure of aggressive behavior for young adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ, Bank L. Family interaction: A process model of deviancy training. Aggressive Behavior. 1984;10:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Punamäki R. Can ideological commitment protect children’s psychosocial well-being in situations of political violence? Child Development. 1996;67:55–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punamaki RL, Sulieman R. Predictors and effectiveness of coping with political violence among Palestinian children. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;29:67–77. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1990.tb00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamäki R, Miller T, El-Sarraj E. Does war beget child aggression? Military violence, gender, age and aggressive behavior in two Palestinian samples. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:231–244. doi: 10.1002/ab.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier C. Impact of internal political violence in Colombia on preadolescents’ well-being: Analysis of risk and protective factors; Paper presented at the 20th Biennial International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development; Würzburg, Germany. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh N, Javdani S, Finy SM, Verona E. Gender differences in emotional risk for self- and other-directed violence among externalizing adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:106–117. doi: 10.1037/a0022197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirlow P, Murtagh B. Belfast: Segregation, Violence and the City. London: Pluto Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Slone M. Growing up in Israel: Lessons on understanding the effects of political violence on children. In: Barber BK, editor. Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence. NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Struch N, Schwartz SH. Intergroup aggression: Its predictors and distinctness from in-group bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:364–373. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S, editors. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin LW, editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma and transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Cambridge, MA, US: Basil Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler LM, DiFluvio G, Burke TK. Resilience and marginalized youth: making a case for personal and collective meaning-making as part of resilience research in public health. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]