Abstract

Using the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction, this study examines the effects of exposure to sexual content on television by genre, specifically looking at comedy, drama, cartoon, and reality programs, on adolescents’ sex-related cognitions and behaviors. Additionally, we compared the amount and explicitness of sexual content as well as the frequency of risk and responsibility messages in these four genres. Findings show that overall exposure to sexual content on television was not related to teens’ engagement in sexual intercourse the following year. When examined by genre, exposure to sexual content in comedies was positively associated while exposure to sexual content in dramas was negatively associated with attitudes regarding sex, perceived normative pressure, intentions, and engaging in sex one year later. Implications of adolescent exposure to various types of content and for using genre categories to examine exposure and effects are discussed.

Keywords: television, integrated model of behavioral prediction, sexual behavior, television genres, adolescents

The sources and content of sex-related information that adolescents receive have important consequences for their subsequent knowledge and behavior (Berenson, Wu, Breitkopf and Newman, 2006; Bleakley, Hennessey, Fishben and Jordan, 2009; Kirby, 2002). Thus, parents, policy makers, and child advocates worry about adolescents’ exposure to sexual content in the media. Concerns about teen pregnancy and STD rates are among the foremost concerns outlined in the Surgeon General’s (2001) “Call to action to promote sexual health and responsible sexual behavior.”

Concern regarding the link between adolescents’ exposure to sexual media content and their initiation of sexual activity may be warranted because teens report various media among their primary sources of information about sexual behavior (Bleakley, Hennessey, Fishbein and Jordan, 2009; Hoff, Greene and Davis, 2003). Furthermore, studies indicate that watching more sexual content in the media contributes to sexual activity among adolescents (e.g., Brown et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2004; Hennessey, Bleakley, Fishbein and Jordan, 2009; Pardun, L’Engle and Brown, 2005). For example, Martino and colleagues (2005) surveyed non-sexually active 12- to 14-year-old teens regarding their degree of exposure to 23 popular television programs containing sexual talk and behaviors. One year later, this sexual media exposure was positively related to teens’ beliefs that the majority of their peers were having sex and their feelings of self-efficacy regarding safe-sex practices. Conversely, exposure was negatively related to the teens’ expectations of negative consequences of sex. Each of these psychosocial outcomes was in-turn significantly predictive of teens’ initiation of sexual intercourse by the time of the second interview.

In another longitudinal study, Collins and colleagues (2004) twice surveyed a national sample of 12- to 17-year-olds over a one-year interval. The researchers examined the role of overall exposure to sexual content in a sample of television shows popular with teens, their relative exposure to messages in the sample of programs regarding the risks and responsibilities of sex, and exposure to sexual talk versus behavior in the programs. They found that for those who were virgins at the start of the study, watching programs high in sex content was a significant predictor of sexual intercourse initiation a year later after controlling for a number of other related factors (e.g. age, parent education, and sensation-seeking). Results did not differ based on exposure to sex-related talk versus behavior. Additionally, they found that African American teens with high exposure to programs with risk and responsibility messages were less likely to engage in intercourse, though this relationship was not found for teens from other racial groups. In a subsequent analysis of the same data, the group found that teens with higher exposure to sexual television content during the baseline survey were more likely to experience unplanned pregnancies within the following three years (Chandra et al., 2008).

Using similar designs, Brown et al. (2006) and Bleakley et al. (2008) queried adolescents about their sexual behavior and media diet, including television, movies, music, and magazines. Content analyses were conducted to determine the amount of sexual content in the media listed by teens, and then participants were re-interviewed one or two years later. Both studies found that teens exposed to a heavier diet of sexual content across media were more likely than those who were less-exposed to such content to have had sexual intercourse in the time between interviews. It is not yet clear, however, whether significant relationships with sexual behavior may exist for teens’ exposure to sex content within a particular medium (e.g. television), which are obscured in combination with other media sources.

To promote healthy sexual behavior among teens, one particular charge from the Surgeon General’s call to action (2001) is directed at media producers: “With respect to media programming, the portrayal of sexual relationships should be mature, and honest, and responsible sexual behavior should be stressed” (p. 16). However, a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation (Kunkel, Eyal, Finnerty, Biely and Donnerstein, 2005) indicates that television content of a sexual nature (i.e. talk about sex and depiction of sexual behaviors) has been steadily rising since 1998. Specifically, a detailed content analysis of a composite week of television programming in 1998 revealed 56% of programs contained at least some sexual content. This proportion grew to 64% of television shows in 2002, reaching 70% in 2005.

Of further note is the fact that television messages reflecting the risks and responsibilities of sexual behavior (e.g. STDs, contraception use, the benefits of waiting to have sex) have not risen at the same rate. Only 9% of television programs with sexual content contained at least one risk or responsibility message in 1998. This rate rose only to 14% in 2005, despite the fact that 70% of programs overall contained sexual content. Programs conveying a primary emphasis on the risk and responsibilities associated with sex were particularly rare, accounting for only 1% of shows analyzed in each year. A recent meta-analysis indicates that the rate of these messages per hour on primetime television has decreased from 0.47 in 1987 to 0.24 messages per hour in 2004 (Hetsroni, 2007). Thus, while the majority of television programming contains sexual content, only a small number of those programs present sexual behavior in a realistic and responsible manner (e.g. reflecting possible negative consequences of sexual initiation as well as appropriate practices for avoiding unplanned pregnancies and STDs).

The possibility remains that not all sexual content in the media is “created equal.” That is, combining different genres of content in one estimate of exposure, as the studies described above have done, may obscure stronger underlying relationships. Television genres represent a “taxonomy” of programs, categorized by certain content element combinations, and as such may contain different messages regarding sexual behavior (Bielby and Bielby, 1994; Neale, 2008). As described by Bielby and Bielby (1994):

Television genres are conventions regarding the content of television series – formulas that prescribe the format, themes, premises, characterizations, etc. In contemporary television, consensus among writers, producers, programmers, advertisers, and audiences over the boundaries of genres is probably greater than in any other area of popular culture. Ideas for new series are “pitched” in terms of widely recognized genres, while network scheduling decisions, advertisers’ purchasing decisions, and audience viewing patterns are all based, to some extent, upon shared understandings about program categories (p. 1292).

Within primetime television, Bielby and Bielby (1994) describe situation comedies, drama programs and reality shows as particularly “basic” genres within the industry.

Genres differ both in how much sexual content programs contain, as well as in the nature of sexual content portrayals. For example, programs in one genre may tend to include more plotlines or discrete messages about unplanned pregnancies or STDs, which could serve as a warning to teens about the negative consequences of sex. Conversely, programs representative of other genres may tend to portray sex as fun and free of risks or negative consequences. To the extent these varying patterns of sex content portrayals do exist, they likely differ in their impact on teens’ sex-related cognitions and behaviors as well.

Kunkel et al’s (2005) content analysis suggests that genre differences do exist. The authors found that among shows in a composite week of television programming, 87% of both comedy and drama series contained sexual content compared to only 67% of talk shows and 28% of reality programs. Though comedies and dramas were fairly equal in their propensity to contain sex-related talk (i.e. 85% and 83% of programs respectively), drama series more commonly depicted sexual behaviors (47%) compared to comedies (39%). Dramas were also slightly more likely to contain risk and responsibility messages (18% of programs) than comedies (13%). This difference was even more pronounced when comparing exclusively primetime shows 17% of primetime drama programs contained risk and responsibility messages, compared to 5% of comedy shows.

Furthermore, violence has been found to differentially affect behavior based on program genre. In a meta-analysis of the influence of televised violence on aggressive behavior, Paik and Comstock (1994) found evidence that violent content portrayed in cartoons and other fantasy programs had greater impact than that of other genres such as sports programs, news, and westerns. Though all genres of programming indicated a positive link between violent content and aggressive behavior, there was a wide range in the magnitude of these effects.

It is not yet clear, however, whether the genre differences in sexual content hold among the programs most popular with adolescents or how the differences in content by genre may influence their behavior. Guided by the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction (Fishbein, 2008; Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010), we analyzed exposure to sexual content in television separately by genre to examine how variations in content lead to differences in their influence on adolescents’ sexual behaviors. The present study utilized data from the Annenberg Sex and Media Study (ASAMS) to investigate relationships among adolescents’ exposure to sexual content in various television genres, and sex-related psychosocial and behavioral outcomes. In this analysis we included four television genres found to be most popular with teens surveyed for ASAMS: cartoons1, comedies, dramas, and reality programs.2

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The goals of the present study were two-fold. First, we examined the differences in sex content by genre in the television programs that teens watch most. Specifically, we were interested in potential variations in the overall amount of sexual content (i.e. combined talk and depiction), as well as what differences there were in sexual content portrayals by genre (i.e. explicitness of sex depicted or implied and number of risk/responsibility messages).

Research Question 1a: Are there differences in the amount of sex content by genre within the television shows that adolescents watch most?

Research Question 1b: Are there differences in the portrayal of sex content (i.e. frequency of risk/responsibility messages and explicitness of sexual behavior depicted or discussed) by genre within the television shows that adolescents watch most?

Additionally, guided by the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction, we investigated whether possible differences in amount and nature of sexual content by genre are associated with differences in the relationships between exposure and adolescents’ sexual cognitions and behaviors. The theoretical principles of the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction (Fishbein, 2008; Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010) are derived from the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), the health belief model (Janz and Becker, 1984; Rosenstock, 1974), and social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977; 1997). The Integrated Model contends that the best predictor of behavior is one’s intention to perform or not perform the behavior, and that intention is determined by some combination of an individual’s attitudes, perceived social normative pressure, and self-efficacy regarding the particular behavior (Fishbein, 2008; Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010). These constructs, in turn, are determined by underlying beliefs held by the individual regarding the outcomes expected by performing the behavior (i.e. attitudes), the normative expectations of specific social referents regarding the behavior (i.e. perceived social normative pressure), and the ability to perform the behavior in the face of possible barriers (i.e. self-efficacy). Moreover, the theory contends that these beliefs may be formed or altered in response to external sources, including the media.

The Integrated Model assumes that behavior is primarily determined by intentions, although one may not always be able to act on one’s intentions due to prohibitive environmental factors or a lack of skills and abilities. A measure of self-efficacy is often used as a proxy for the factors influencing actual control, rather than directly measuring environmental factors, skills, and abilities. Therefore, behavior is considered a function of both intentions and self-efficacy (Webb and Sheeran, 2006). Further, background variables such as personality traits, demographic characteristics, media exposure, and past behavior, are expected to influence behavior only indirectly. That is, their influence on behavior is assumed to be mediated by the more proximal variables in the Integrated Model. In the reasoned action literature, this is known as the assumption of “theoretical sufficiency,” but whether a given background variable of interest will or will not have an effect on the more proximal variables is an empirical question. Many prior studies have used the Integrated Model to show how background variables such as media exposure affect the model’s psychosocial constructs among a number of health-related behaviors. These studies included analyses of risky behaviors like adolescent sex initiation (Sieverding, Adler, Witt and Ellen, 2005), smoking initation (Flay et al., 1994; Harakeh et al., 2004), and unsafe driving among teens and adults (Armitage, Norman and Conner, 2002; Desrichard, Roche and Begue, 2007; Elliott, Armitage and Baughan, 2003), as well as healthy behaviors such as cancer screening (Jennings-Dozier, 1999), condom use (Armitage, Norman and Conner, 2002) and exercise (Rhodes, Courneya and Jones, 2004).

Because the predictive values of attitudes, perceived norms and perceived self-efficacy vary between populations and target behaviors (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2009), we inquired about which of the constructs would be most predictive of sexual behavior for our sample of adolescents. It is conceivable that any combination of these three psychosocial constructs could significantly influence teens’ intentions to engage in sexual behavior. Thus,

Research Question 2: Which of the three direct psychosocial constructs in the Integrated Model (i.e. attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and self-efficacy) most strongly predicts adolescents’ intentions to engage in sexual behavior?

Given the prior findings regarding the influence of exposure to sexual content on television (e.g., Martino et al., 2005; Collins et al., 2004), we anticipated a positive relationship between adolescents’ total exposure to sexual content on television and their sexual behavior. Thus,

Hypothesis 1: Overall exposure to sexual content on television (i.e. all television programs combined) has a positive association with adolescents’ sexual behavior.

Finally, we anticipated that exposure to sexual content in each genre will either favorably or unfavorably influence attitudes, perceived norms, and self-efficacy, which in turn will affect behavioral intention and ultimately sexual behavior. Therefore, we ask if there are variations in the impact of sexual content by genre, and how differences, if any, might operate through the Integrated Model. Specifically, one possibility is that the quantity of sexual messages drives potential differences, such that adolescents who view genres containing the most sexual content would have attitudes, perceived norms, and/or self-efficacy that are more favorable towards sex, and consequently will have higher intentions to engage in sexual behavior and higher rates of actual sexual behavior. Conversely, it may be the nature of sex content that matters, in which case adolescents who commonly view programs with certain types of messages about sex will have more pro-sex attitudes, perceived norms, and/or self-efficacy, as well as increased intentions and rates of sexual behavior, regardless of the overall amount of sexual content in that genre. Further, it is possible that exposure to sexual content in each genre differentially affects distinct paths in the Integrated Model. Because this is the first known study to examine differences in television’s impact on adolescents based on genre, we approach these potential differences as research questions. Thus,

Research Question 3: Does exposure to sexual content on television by genre differentially affect adolescents’ sexual behavior?

Research Question 4: Does exposure to sexual content on television by genre differentially affect the three direct psychosocial constructs of in the Integrated Model (i.e. attitudes, perceived norms, self-efficacy) that predict intention to have sex in the next 12 months?

Methods

The Annenberg Sex and Media Study (ASAMS) was a five-year investigation of the relationship between sex in the media and self-reported sexual behavior in adolescents. It was designed to investigate whether sexual content in the media shapes adolescents’ sexual development. Data presented in this paper are part of two major components: (1) the second and third waves of a three wave web-based longitudinal survey of youths 14–16 years of age at time of recruitment, and (2) a content analysis of sexual content in television shows.

Survey

Data collection took place via a web-based survey fielded during the spring and summer of 2005, 2006, and 2007. Adolescent respondents were recruited through print and radio advertisements, direct mail, and word of mouth to complete the survey. Respondent eligibility criteria included age at the time of the initial survey (14, 15, or 16) and race/ethnicity (White, African-American, or Hispanic). The sampling strategy was quota-driven with a desire for roughly equal sample sizes in all Race*Age*Gender cells (a 3*3*2 design). In practice, adolescent Hispanic respondents in the Philadelphia metropolitan area were extremely difficult to locate and recruit, so their cell frequencies are low.

The survey was launched in April 2005 following a test of the technology and a pre-test of the survey instrument. The survey was accessible from any computer with Internet access. Participants were given the option of taking the survey at the University or an off-site location (e.g. home, school, or community library). Respondents were assigned a password to access the survey, as well as an identification number and personal password to ensure confidentiality and privacy protection. Respondents were compensated $25 dollars upon completion of the survey at each wave, and on average, took one hour to complete the survey. Those respondents who completed all 3 waves of the survey received a bonus of $25. After submitting respondent assent/parental consent forms, 547 adolescents ages 14 to 16 completed the survey at Wave 1 (in 2005). There are a small number of missing values although retention rates over the three waves of data collection were high (87% of the initial sample were successfully recontacted in all waves and 94% of the initial sample participated in at least 2 of 3 waves). The analysis presented in the paper utilized respondents who completed both the second and third waves (N=474); the respondents were 63.1% female, 43.0% African-American, 42.8% White, 11.2% Hispanic, and 3.0% other, and had a mean age of 15.96 years in the second wave and 16.98 in the third wave.

Content Analysis

In the survey, respondents were asked how frequently they watch specific television programs. The list of television shows was constructed to reflect popular titles for teenagers and/or the general public at the time of the survey; it was compiled from website rankings (including www.top5s.com/tvweek), an audience research company (TRU data), and pilot surveys. This list was created to provide depth and breadth among programs, acknowledging that all shows could not be represented.

The most commonly viewed television programs – among the respondents (according to our survey results) – were selected for content analysis. For each program identified, the sample included three randomly selected episodes; the unit of analysis was the television episode.3 The four most prevalent genres of television programs included in both the survey and content analysis were cartoons (N=7), comedies (N=13), dramas (N=9), and reality (N=11), resulting in a total of 40 programs included in this analysis. The titles of the shows in each genre are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Television Programs Included in Each Genre

| Cartoon | Comedy | Drama | Reality |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Dad | All of Us | 7th Heaven | American Idol |

| Boondocks | Boy Meets World | Degrassi | America’s Next Top Model |

| Family Guy | Chappelle Show | Desperate Housewives | Extreme Home Makeover |

| Futurama | Fresh Prince of Bell Air | ER | Fear Factor |

| Simpsons | Friends | Gilmore Girls | The Gauntlet |

| Southpark | Girlfriends | Grey’s Anatomy | Parental Control |

| Spongebob Squarepants | Half & Half | House | Pimp My Ride |

| One on One | OC | Real World | |

| Seinfeld | One Tree Hill | Room Raiders | |

| Sex in the City | Super Nanny | ||

| That 70s Show | Surreal Life | ||

| That’s So Raven | |||

| Will and Grace |

Source: ASAMS Content Analysis Year 2

The sexual content variables were constructed according to the Integrated Model of Behavioral Prediction and followed coding procedures consistent with prior content analyses of sexual content (Kunkel et al., 2005). A team of fifteen undergraduate students were recruited and trained over the course of an academic year to recognize and code the variables. The sharing of similar backgrounds among coders is what aids reliability (Krippendorff, 2004; Neuendorf, 2002). All coders were college sophomores and juniors. Weekly meetings, which included in-depth discussion of the codebook and practice group coding of media content, provided consistency and reliability across coders, by reducing each coder’s subjective biases (Berelson, 1952; Riffe et al., 1998).

Three variables of theoretical interest for this analysis were overall sex content, explicitness of sexual content, and number of risk and responsibility messages. Overall sexual content was coded as the proportion of sexual content in each program (i.e. the prevalence of sexual talk and behavior). This item is a dichotomous measure that indicates whether a television program had none/a little or some/a lot of sexual content (% agreement = 81.0%; Krippendorf’s Alpha=.62); 72.5% of programs had some/a lot of sexual content. Explicitness of sexual content is the extent of topics discussed or depicted in each program. This variable was operationalized with a seven-point scale ranging from 0 to 6 which was created by combining a series of dichotomous items concerning whether certain sexual behaviors were discussed or portrayed in a show, from the least to most explicit (i.e. anal sex) (M=3.75; SD=2.08). The percent agreement between coders for all items used for this scale ranged from 76.2% to 100% (average agreement = 94.0%; Krippendorf’s Alpha for all items in scale = .64). The explicitness scale was created in the same fashion as that by Hennessy et al (2008). Finally, risk and responsibility was conceptualized in a similar fashion as Kunkle et al (2005) as the prevalence of depictions or discussion of sexual patience, sexual precaution, or sexual risks or negative consequences. This variable was coded as the total number of messages per program (M=0.51; SD=0.93) that concerned the following topics: condoms, safe sex, abstinence, unplanned pregnancy, abortion, HIV, and STDs. The percent agreement between coders for items used for this scale ranged from 97.6% to 100% (average agreement = 99.0%; Krippendorf’s Alpha for all items in scale = .76). Examples include scenes such as a character uses an EPT test to find out if she has accidentally become pregnant, and a male character and a female character decide not to have sex because a condom is not available.

Exposure to Sex Content by Television Genre

Respondents were asked to rate their amount of exposure to each television program on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (often), measured in the second wave of the survey. The respondents’ reported exposure and the content analysis’ overall sexual content rating were multiplied together for each program. These scores were summed for each genre resulting in sexual content exposure measures specific to cartoons, comedies, dramas, and reality shows (Cartoons M=4.97; SD=4.40; Comedies: M=10.36; SD=6.86; Dramas: M=6.07; SD=5.42; Reality: M=4.22; SD=4.25); these four measures were each standardized since there were different numbers of titles between genres. Additionally, an exposure measure for sexual content among all television shows was constructed summing the standardized scores of the four genres; this construction of the variable in this fashion accounts for there being different number of titles in each genre, such that one genre having more titles does not overwhelm the measure. The analysis used exposure measures asked in the second wave of the study.4

Integrated Model Measures

The survey collected measures of intention, attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and self-efficacy with respect to engaging in sexual intercourse in the next 12 months. All items were on a 7-point scale that ranged from −3 to 3, measured in the second wave of the survey. For the direct measure of intention, respondents were asked to rate the following three items ranging from unlikely to likely: “I am willing to…,” “I will…,” and “I intend to…” “have sexual intercourse in the next 12 months.” The scale of intention was created by computing the mean of the three items (alpha = 0.96; M=0.10; SD=2.26). For attitudes, respondents were asked five items: “My having sexual intercourse in the next 12 months would be…” “bad/good,” “foolish/wise,” “unpleasant/pleasant,” “not enjoyable/enjoyable,” and “harmful/beneficial.” The mean of these items was computed to create the scale of attitudes (alpha=0.91; M=0.24; SD=1.60). Regarding perceived normative pressure, four items were asked of the respondents: “Most people who are important to me think I should not/should have sexual intercourse in the next 12 months,” “Most people like me will not/will have sexual intercourse in the next 12 months,” “Most people like me have not had/have had sexual intercourse,” and “Most people like me have not had/have had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months.” These items were averaged to compute the scale of perceived normative pressure (alpha=0.81; M=−0.10; SD=1.65). The survey measured self efficacy using a single item (M=0.91; SD=2.24) that asked “If I really wanted to I am certain that I could not/could have sexual intercourse in the next 12 months (Answer even if you don’t have a boyfriend or girlfriend).” Like content exposure items, the analysis employed Integrated Model measures that were collected in the second wave.

Dependent Variable – Had Sex in the Past 12 Months

Respondents were asked, “Have you ever had sex (i.e. penis in vagina) with a partner?” The variable was coded into a dichotomous variable that indicates whether they had sex in the past 12 months; 51.0% reported having had sex in the past 12 months. This measure of behavior was collected in the third wave, one year after the Integrated Model and exposure items were measured.

Analyses

To determine differences in sexual content between genres, a series of one way analysis of variance tests (ANOVA) with planned contrasts was conducted; the dependent variables from the content analysis were overall amount of sexual content, explicitness of sexual behaviors, and risk and responsibility. To consider the direct effect of exposure on having had sex in the past 12 months, logistic regression models were conducted separately for each of the genre and overall TV measures, and another with all four genres as predictors.

To examine whether attitudes, perceived normative pressure, or self-efficacy was most predictive of intention to have sex in the next 12 months, a path analysis of the basic raw form of the Integrated Model was conducted using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2006) because of the program’s ability to estimate models with categorical endogenous variables. In this model, paths led from attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and self-efficacy to intention. The error terms for attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and self-efficacy were allowed to correlate with each other.5 Finally, having had sex in the past 12 months was predicted by intentions and self-efficacy.

Finally, to understand how exposure to sexual content by genre works through the Integrated Model, a model was estimated in which the exposure measures of sexual content in each of the four genres were exogenous to the Integrated Model. Each genre had paths to attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and self-efficacy. The four genre exposure measures were all correlated with each other.

Because having had sex in the past 12 months was dichotomous, both models employed a robust weighted least squares estimation method. To assess the fit of the models, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Chi-Square were estimated;6 conventional standards for good model fit for the CFI is .95 or higher and .05 or lower for the RMSEA (Hu and Bentler, 1995; Kaplan, 2000; Kline, 2005).7

Results

Table 2 presents the differences in sexual content between genres. There was moderate evidence for differences in amount of sexual content; reality TV had significantly less overall sexual content than dramas. Regarding explicitness, reality TV had significantly less explicit sexual behaviors than cartoons, comedies, and dramas. Finally, dramas on average presented significantly more risk and responsibility messages than cartoons, comedies, and reality programs.

Table 2.

Amount and Explicitness of Sexual Content, and Risk and Responsibility Messages by Television Genre

| Means | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Cartoons (N=7) | Comedies (N=13) | Dramas (N=9) | Reality (N=11) | F | |

|

|

|||||

| Amount of Sexual Content† | 0.71 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 2.81 |

| Explicitness of Sexual Content†† | 4.14 | 4.23 | 5.00 | 2.27 | 4.42** |

| Risk and Responsibility††† | 0.57 | 0.54 | 1.56 | 0.09 | 4.40** |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Source: ASAMS Content Analysis Year 2

Note: Analysis is a ANOVA with planned contrasts

Reality is significantly lower than dramas (p<.01).

Reality is significantly lower than cartoons (p<.05), comedies (p<.05), and dramas (p<.01).

Drama is significantly higher than cartoons (p<.05), comedies (p<.05), and reality (p<.001).

Table 3 presents the direct effect of exposure to sexual content in each of the four genres and all programs combined on having sex in the past 12 months. The effect of each genre was first estimated separately (Models 1–4) and then together (Model 6) to account for the correlation among the exposure scores; additionally, the effect of exposure to sexual content among all TV programs was measured (Model 5). Exposure to sexual content when all TV programs were combined (Model 5) did not predict having had sex. Looking at the genres when modeled separately, only sexual content exposure in comedies (Model 2) significantly increased the likelihood of having had sex (β = .15; p<.01). When all genres were in the same model (Model 6), exposure to comedies positively predicted having had sex (β = .27; p<.001), while dramas negatively predicted having had sex (β = −.17; p<.01); neither cartoons nor reality programs significantly predicted having had sex.8

Table 3.

Direct Effect of Exposure to Sex Content on Having Had Sex in the Past 12 Months

| Regression Coefficients Predicting Having Had Sex in the Past 12 Months: b (β) (Exp(b))

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|

|

||||||

| Cartoon | −.07 (−.04) (0.93) | - | - | - | - | −.18 (−.10) (0.83) |

| Comedy | - | .27** (.15) (1.31) | - | - | - | .50*** (.27) (1.62) |

| Drama | - | - | −.14 (−.08) (0.87) | - | - | −.32** (−.17) (0.74) |

| Reality | - | - | - | −.08 (−.04) (0.93) | - | −.09 (−.05) (0.91) |

| All Programs | - | - | - | - | .00 (.00) (1.00) | - |

| N | 447 | 446 | 445 | 445 | 443 | 443 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .06 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Source: ASAMS Longitudinal Survey and Content Analysis

Notes: Analysis is a series of logistic regression models. The exposure to sex content in each genre and sex content in for all TV programs were from the second wave of the survey and content analysis. The having had sex in the past 12 months dependent variable is from the third wave of the survey.

Prior to any examination of how exposure to sexual content in each genre may influence behavior via the Integrated Model, it is first necessary to consider relationships within the model by itself without the background exposure measures. The raw model (i.e. without any exposure measures; N = 439) met all conventional standards of model fit (Chi-sq = 2.88, p = .24; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .03). Adolescents’ attitudes towards sexual initiation was the strongest predictor of intention (β = .42; p<.001), followed by perceived normative pressure (β = .36; p<.001) and self-efficacy (β = .16; p<.001). Finally, having had sex in the past year was significantly predicted by intention (β = .55; p <.001) but not self-efficacy.

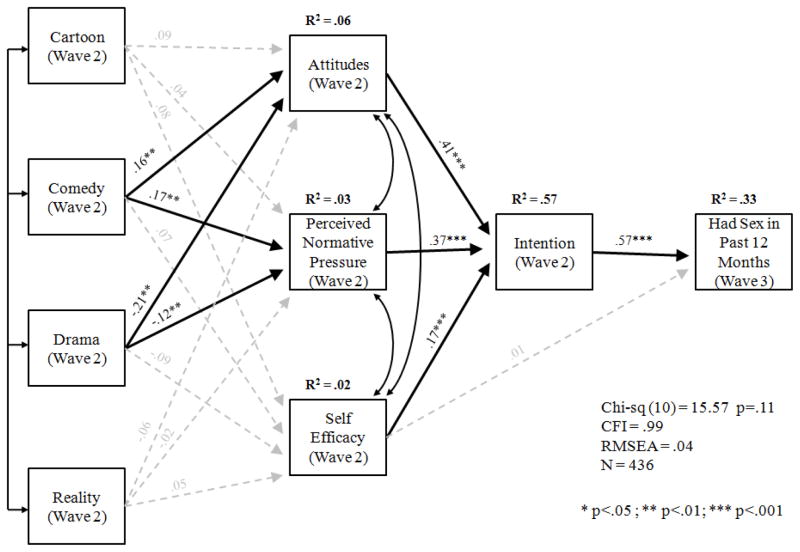

Figure 1 presents the path analysis testing how exposure to sexual content in the various genres worked through the Integrated Model. Similar to the previous model without the exposure measures, this model also meets conventional standards of good model fit (Chi-sq (10) = 15.57, p = .11; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04).

Figure 1. Path Analysis of Exposure to Sex Content in Television Genres on Having Sex among Adolescents through the Integrated Model.

Source: ASAMS longitudinal survey and content analysis. Notes: Had sex in past 12 months is from wave 3; all other variables were measured one year prior in wave 2. Analysis uses a robust weighted least squares estimation method conducted using Mplus software. Non-significant paths are dashed light grey lines. All coefficients are standardized. To measure R2 of categorical dependent variables, Mplus uses a continuous latent response variable approach (see McKelvey and Zavoina, 1975); thus, R2 for had sex in past 12 months uses this approach.

Within this model, exposure to sexual content in comedies positively predicted attitudes (β = .16; p<.01), while dramas negatively predicted attitudes (β = −.21; p<.01). Similarly, perceived normative pressure was positively predicted by comedies (β = .17; p<.01) and negatively predicted by dramas (β = −.12; p<.05). Exposure to sexual content in cartoons and reality programs did not have a significant effect on attitudes, perceived normative pressure, or self-efficacy. Thus, none of the genres predicted self-efficacy. Like the raw model without the exposure variables, attitudes was the strongest predictor of intention in this model as well (β = .41; p<.001), followed by perceived normative pressure (β = .37; p<.001) and self-efficacy (β = .17; p<.001). Having had sex in the past 12 months was significantly predicted by intention (β = .57; p<.001) but not by self-efficacy.9 R2 statistics for all endogenous variables are presented in Figure 1.

Further, there are significant indirect effects from exposure to sexual content by genre to having had sex in the past 12 months. The indirect effects were estimated in Mplus, which multiplies the path coefficients together. There were significant total indirect effects for comedies (β = .08; p<.01) and dramas (β = −.08; p <.01). For comedies, the indirect paths that went through attitudes (β = .04; p<.05) and perceived normative pressure (β = .04; p<.05) were significant. For dramas, there was a significant indirect effect through attitudes (β = −.05; p<.01). Cartoons and reality programs had no significant indirect effects.10

Discussion

Among television programs popular with adolescents, there were clear distinctions between genres in the amount and explicitness of sexual content and the number of risk and responsibility messages. There was some evidence that reality programming had less overall sex content than the other genres, specifically dramas. This may be due to the fact that sexual content would be out of place in many of the reality programs, such as Super Nanny or Extreme Home Makeover. Additionally, the sexual content that does exist in reality programs was less explicit than in the other genres. Finally, dramas had substantially more risk and responsibility messages than the other genres almost three times as much on average.

Combining the data from the content analysis with the survey allowed for insight into how exposure to the sexual content among teens influenced their engagement in sexual intercourse. Contrary to our predictions, we found that overall exposure to sex content on TV did not predict having had sex among adolescents in this sample. Though consistent with findings from Bleakley et al. (2008) and Pardun, L’Engle and Brown (2005), our results are contrary to those of Collins and colleagues (2004) and Martino and colleagues (2005), which indicated positive associations between global estimates of exposure to sexual content on television and adolescents’ sexual behavior. These differences may be due to changes in the programs that are popular with teens (e.g. more viewing of reality television shows), or they may reflect methodological differences between studies. For example, the present study includes adolescents who were 14–16 years of age at recruitment, while Martino’s and Collins’ studies participants were as young as 12. Future studies should look carefully at potential differences in relationships for older and younger adolescents. Furthermore, these prior studies involved only 23 programs popular with teens, which may have had particularly high concentrations of sexual content. Our study analyzed the 40 television programs in the four genres most commonly viewed by our sample, and thus may have contained more variability in content.

The third and fourth research questions, which sought potential differences in the Integrated Model’s psychosocial constructs, intention, and behavior based on television genre, yielded the most interesting results. Our analyses indicated diverse relationships between individual genres and behavior that could not be explained by differences in quantity of sexual content alone. Cartoons and reality programs did not have a significant impact on attitudes, perceived normative pressure, or self-efficacy when controlling for the other three genres, and therefore did not have any effect on having had sex. In contrast, the other three genres had roughly the same amount and explicitness of sexual content. Moreover, exposure to sexual content in comedies was positively associated and exposure to sexual content in dramas was negatively associated with the two constructs that were most predictive of intention: attitudes and perceived normative pressure. Because exposure to sexual content in comedies and dramas affected these two dominant paths, they produced a change in teens’ sexual behavior, but in opposite directions.

This paper went one step further than other studies by breaking estimates of total sex exposure into genre categories. Indeed, we found that analyzing exposure to sexual content by genre not only explained significantly more of the variance in behavior compared to exposure to total television sex content, but also that the relationship was not consistent among genres. Looking specifically at attitudes, exposure to sexual content in comedies made adolescents think more positively about having sex, while dramas made them think more negatively. The same opposite effects of comedies and dramas on perceived normative pressure were also found. What this suggests is that methodologically, when analyzing exposure to sexual content in television programs, considering all programs together as one unit is misleading because diverse effects of the specific genres are obscured. However, when television programs are analyzed separately by genre the differential effects of television exposure to sexual content are revealed.

The difference in effects of the four genres on attitudes and subsequent behavior reflected patterns of differences found in the content analysis. Cartoons, comedies, and dramas were all statistically equivalent in their amount of sexual content and explicitness of sexual content. The variable in which one of these three genres differed was risk and responsibility; dramas had many more messages about the risks and responsibilities of sex than did cartoons and comedies.11 Therefore, we suspect dramas may have had their negative effect on attitudes because the risk and responsibility message which they contained were counteracting the sexual content, which made adolescents think more negatively about sex. Comedies, on the other hand, had significantly fewer risk and responsibility messages, but an equal amount of overall sexual content as dramas. This was consistent with our finding that exposure to sexual content in comedies boosted teens’ sex-related attitudes (i.e. made them feel more favorably about having sex), and had a subsequent positive association with intention to have sexual intercourse as well as the actual behavior.

Additionally, it is possible that some further aspect of comedies renders the sexual content they contain more influential on adolescents’ increased likelihood to engage in sexual behaviors. That is, some characteristic of the structure or content of comedy programs may lead viewers to process the messages within them differently than other genres, leading to their heightened impact. One possibility may be the use of humor. Research from other content and outcome domains provide guiding examples of the influence of humor for further exploration in this area. In the realm of media violence, analyses have indicated particular risk of learning and imitation of aggression when violence is portrayed in a humorous light (e.g. Berkowitz, 1970; Gunter and Furnham, 1984; Villani, 2001). Scholars have interpreted this finding to mean that humor likely “trivializes” violence, making it seem less serious or harmful (Gunter and Furnham, 1984; Potter and Warren, 1998). The humorous nature of sexual content in television comedies may have a similar affect on adolescents’ perceptions of sex. That is, sexual intercourse may seem more “trivial” and less consequential to them when depicted in a comical context, leading to more favorable attitudes as well as increased learning and imitation.

Another intriguing possibility has been studied in regards to the influence of political humor in late-night comedy talk shows (e.g. Bill Maher and Conan O’Brien). Experimental studies have shown that the impact of political jokes can be quite powerful, and may even show a lagged effect whereby influence increases with time (Nabi, Moyer-Guse, and Byrne, 2007; Young, 2008), also known as the “sleeper effect.” Specifically, humor appears to motivate viewers to process content (i.e. because it is entertaining), while disrupting their critical scrutiny of messages. In addition, though it is thoroughly attended to and processed, content that is classified as humorous is often “discounted” by viewers as “just a joke,” and irrelevant to attitudes and judgments. Over time, the content of the discounted message is remembered, but the source of that message is not, leading to an increased opportunity for the content to impact attitudes and judgments (Nabi, Moyer-Guse, and Byrne, 2007; Young, 2008). It is possible that teens may similarly discount humorous sexual television content, while still carefully processing information and suspending defensive criticism. This humorous sexual content may then have subtle, yet powerful impact on teens’ attitudes and behaviors, particular if source and content have been disassociated over time.

In contrast, the nature of sexual content portrayal in dramas may lead to less trivialization of sexual behavior among teen viewers. Davis and Mares (1998) found this to be true in a study of the influence of talk shows on adolescents. They found that more exposure to talk shows was associated with higher perceived frequency of the deviant behaviors discussed (e.g. teen pregnancy, multiple sexual partners, and abuse) among teens. Viewing more talk shows, however, was inversely related to trivialization; teens who watched more of this content rated the depicted deviant teen behaviors as more problematic than their peers who watched few or no talk shows. The authors theorized that these findings were driven by the negative reactions of talk show hosts and studio audience members to the deviant behavior of guests, serving to “reinforce traditional moral codes.” They stated, “it looks almost as though talk shows serve as cautionary tales, heightening teens’ perceptions of how often certain behaviors occur and how serious social issues are” (p. 85). As noted earlier, because very few teens in our sample reported watching talk shows, this genre was not included in the content analysis nor asked of respondents in the survey. However, the sex-related risk and responsibility messages and themes in dramas may operate in a similar fashion as deviant behaviors portrayed in talk shows. That is, exposure to messages about the risks (e.g. HIV, pregnancy) and responsibilities of sexual behavior (e.g. birth control, emotional implications for self and partner) embedded in drama narratives may serve to amplify teens’ awareness of the serious implications and negative potential outcomes associated with sexual behavior.

Though the use of longitudinal data strengthens the support for causality in the hypothesized direction (i.e. television sex exposure influences sex-related cognitions and behavior), the possibility remains that the true nature of the relationship is reversed or non-causal. Specifically, it is possible that teens that have already formed intentions to have sexual intercourse are drawn to certain types of programming (i.e. comedies with a lot of sexual content and few risk and responsibility messages; see Bleakley et al., 2008). It may also be that both intention to have sex, and propensity to watch certain genres of programming with more sexual content are caused by some unaccounted-for third factor. Future research should attempt to rule out these possibilities with alternative types of analyses or experimental studies.

In addition, our ability to carefully describe specifics regarding the influence of risk and responsibility messages is limited by the amorphous nature of its conceptualization. A broad range of behaviors is coded as “risk and responsibility,” varying from condom use, to abortion, to sex crimes. Still, findings indicated that these messages broadly serve as a protective factor for teenagers, and we believe it may be more feasible to encourage producers to incorporate more risk and/or responsibility messages into storylines than to eliminate or drastically decrease sex-related media content overall. Future research should separate “risk” from “responsibility” messages more explicitly, to enable more detailed analyses of whether there are differential effects of the two.

Finally, we used common television genre categories, as described by Bielby and Bielby (1994) and others (e.g. Creeber, 2008), for which enough teens in our sample viewed programs to make each genre inclusion valuable. It may be that genres, and the self-evident nature of their taxonomy, may be taken for granted in the industry and in research, by which the current conceptualization of genre in industry and research is not optimal. An examination of existing content analyses reveals very few which explicitly explain what structural or content factors were used to determine genre assignments. What is more, standard media fare is ever-evolving, potentially rendering traditional conceptualizations of “genre” inaccurate. In fact, Turner (2008) urges “Television genres and programming formats are notoriously hybridized…and becoming more so” (p. 8). Further, though statistical power considerations constricted the number of television shows we could include in this analysis, the range of program titles included in this analysis may be somewhat limiting to the generalizability of results. Future research should seek to replicate this research with genre categories consisting of different programs.

Our findings indicate that how programs are broken up and grouped together makes a considerable difference for understanding the effects of television sex content on adolescents. The genre differences uncovered in this study are likely driven by variation in both the number and nature of sexual depictions typically portrayed. These findings are particularly important in light of the increasingly sexual television content that is not only available to but also produced to target adolescents. A prominent example is MTV’s “Skins,” which has met such considerable criticism from parents and child advocates since its premiere in January 2011 that the majority of its original marketers pulled their advertisement funding from the series (PTC, 2011; Schuker, 2011; Stelter, 2011). While episodes of “Skins” feature a cast of teenagers engaging frequently in drug and alcohol use, sexual behavior, and other risky and deviant behaviors, the characters are often not rewarded for these behaviors. On the contrary, the program often depicts the dangers of engaging in these risky behaviors by portraying the offending characters as out of control, unhealthy and unhappy (Marcus, 2011). Our analyses indicate that the influence of programs such as “Skins” on adolescents may depend not only on the amount and explicitness of the sexual content they contain, but also the more nuanced nature of the messages surrounding that content.

Future research needs to provide a better understanding of what characteristics of programs are particularly influential, and how best to conceptualize and operationalize “genre,” in order to more accurately understand television effects. Further, studies should explore whether and how genre effects occur in other media (e.g. movies and music), looking at how other genre types, those that are distinct from genres in television, differentially affect sexual behavior in adolescents. While such an examination was outside the scope of the present study, there is reason to suspect that genre-specific influence is not limited to television.

Acknowledgments

We would first and foremost like to thank the recently deceased Martin Fishbein for his dedication and guidance on this project, and without whom this paper would not exist. Also, gratitude is extended to the many colleagues and friends who have provided advice on this paper. This paper was made possible by Grant number 5R01HD044136 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD.

Biography

Jeffrey A. Gottfried is a doctoral candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and a senior researcher of the Annenberg Public Policy Center. Sarah E. Vaala is a doctoral candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and a researcher in the Annenberg Children & Media Lab. Amy Bleakley is a Research Scientist in the Health Communication Group of the Annenberg Public Policy Center. Michael Hennessy is Senior Research Analyst in Health and Political Communication at the Annenberg Public Policy Center. Amy Jordan is the director of the Media and the Developing Child sector of the Annenberg Public Policy Center.

Footnotes

Though the cartoons included in this analysis could also be described as comedies (see Table 1), we felt that the fact that they are animated instead of live-action sets them apart, and could have implications for how viewers interpret and are influenced by sexual content within them.

It should be noted that talk shows were not included in this study because there were not enough shows that were popular among adolescents to reliably be analyzed. In fact, the only show that might be considered a talk show that was popular among the adolescents in the sample and thereby included in the content analysis and survey was MTV’s TRL.

For a more in depth explanation of the content analysis see Bleakley et al (2008); see also Collins, Elliott and Miu (2009).

The television shows in the survey and content analysis varied between waves of the panel study. Therefore, a repeated measures analysis was deemed inappropriate for this study.

The measurement errors for attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and self-efficacy were correlated with one another. The errors were allowed to correlate since nowhere in the Integrated Model (or its antecedents) is there an explicit theory about the causal ordering of attitude, normative pressure, and self-efficacy. Thus, an appropriate SEM approach here is to estimate the correlations between their error terms (Preacher and Hayes, 2008, p. 882–883). This penalizes the SEM model in terms of R2 for the mediating Integrated Model direct measures. Estimation with correlated errors between attitudes, normative pressure, and self-efficacy has become common (e.g. Hull et al, 2010).

Though X2 was considered as a measure of model fit, it is the least indicative because of sensitivity to larger sample sizes.

Missing data for the logistic regression and SEM models was handled using listwise deletion. Across analyses, the highest percent of missing data was only 8%. With little amounts of missing data, there is no added benefit of handling missing data with a more complicated method than listwise deletion.

There is no evidence of any problems of multicollinearity between the four genre sexual exposure variables. The largest variance inflation factor (VIF) is 1.42, which is well below the convention of 10 or higher being an indicator of multicollinearity (see Dielman, 2005).

The survey contained another measure of sexual behavior, a scale of the extent of sexual behavior in the respondent’s lifetime. This item is an 8-point scale from least to most advanced behavior. A score of 0 means that that respondent had never done any of the behaviors and a score of 7 means that the respondent had done all of the behaviors (Mean = 4.43; SD = 2.16). In the Integrated Model framework, it is theoretically problematic to use this measure as a dependent variable since there is a lack of correspondence of the behavior and time frame between the dependent and mediating variables (i.e. the attitudes, normative pressure, self-efficacy, and intention measures specifically ask about vaginal sex in the next 12 months, whereas this behavior and time frame is not the same for this alternative sexual behavior scale; see Fishbein and Ajzen, 2010). Putting the problem of correspondence aside, a model estimated with this dependent variable presents similar results to the model with the dichotomous variable in Figure 1. The only differences from the model in Figure 1 is that cartoons modestly predicted attitudes (β = .11; p<.05), dramas modestly predicted self-efficacy (β = −.12; p<.05), and self-efficacy significantly predicted the dependent variable of lifetime sexual behavior (β = .13; p<.01). This model shows that exposure by genre did not only have an effect on having had vaginal intercourse, but other sexual behaviors as well. It must be noted, though, that the model does not fit as well as with the model with the dichotomous item as the dependent variable (chi-sq [10] = 19.74, p<.05; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .05), which suggests that the model’s specification is not as appropriate because of the lack of correspondence between the dependent variable and the mediating variable.

An alternative model was tested with direct paths from exposure to sexual content in each genre to intention. To compare this alternative model with the model presented in Figure 1, a chi-square difference test was estimated. This test showed that the addition of the direct effects on intention did not significantly improve the model fit (chi-square for difference testing (4) = 2.86; p=.58), suggesting that the effects presented in Figure 1 are mediated through the indicated pathways, not by direct effects. This finding is also keeping with the Integrated Model’s previously mentioned theoretical sufficiency assumption; that is, behavior is best predicted by intention to perform a given behavior, which is in turn best predicted by attitudes, perceived normative pressure, and self-efficacy regarding the behavior (Fishbein and Azjen, 2010; Hennessy et al, 2010). Additional variables should not improve the prediction of behavior directly, but rather their impact is mediated through these three psychosocial constructs. Model sufficiency is best tested by examining violations in the prediction of intention only, and therefore, this alternative model includes the direct paths to intention; “the test of model sufficiency should be restricted to the prediction of intentions only because all reliable variance in intention should be predicted by attitudes, perceived normative pressure and perceived control [i.e. self-efficacy]” (Hennessy et al, 2010, pp. 233), a statement that is confirmed by this alternative model.

While the effect of cartoons on attitudes only approached significance by traditional conventions (β = .09, p<.10), the effect was in the same direction as comedies. This is consistent with the finding that cartoons had an amount of sexual content as comedies and dramas that was not statistically different, but like comedies did not have as many risk and responsibility messages.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey A. Gottfried, Email: jgottfried@asc.upenn.edu, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, 3620 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104

Sarah E. Vaala, Email: svaala@asc.upenn.edu, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, 3620 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104

Amy Bleakley, Email: ableakley@asc.upenn.edu, Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania, 202 S. 36th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Michael Hennessy, Email: mhennessy@asc.upenn.edu, Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania, 202 S. 36th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Amy Jordan, Email: ajordan@asc.upenn.edu, Annenberg Public Policy Center, University of Pennsylvania, 202 S. 36th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

References

- Abma JC, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Dawson BS. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2002. National Center for Health Statistics: Vital and Health Statistics. 2004;23(24) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Albarracín D. Predicting and changing behavior: a reasoned action approach. In: Ajzen I, Albarracín D, Hornik R, editors. Prediction and Change of Health Behavior. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Norman P, Conner M. Can the Theory of Planned Behaviour mediate the effects of age, gender and multidimensional health locus of control? British Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7:299–316. doi: 10.1348/135910702760213698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson B. Content analysis in communication research. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Berenson AB, Wu ZH, Breitkopf CR, Newman J. The relationship between source of information and sexual behavior among female adolescents. Contraception. 2006;73:274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. Aggressive humor as a stimulus to aggressive responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1970;16(4):710–717. doi: 10.1037/h0030077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielby WT, Bielby DD. All hits are flukes”: Institutionalized decision making and the rhetoric of network prime-time program development. American Journal of Sociology. 1994;99(5):1287–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Hennessy M, Jordan A, Chernin A, Stevens R. Developing respondent-based multi-media measures of exposure to sexual content. Communication Methods and Measures. 2008;2:43–64. doi: 10.1080/19312450802063040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. It works both ways: The relationship between exposure to sexual content in the media and adolescent sexual behavior. Media Psychology. 2008;11:1–19. doi: 10.1080/15213260802491986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, L’Engle KL, Pardun CJ, Guo G, Kenneavy K, Jackson C. Sexy media matter: Exposure to sexual content in music, movies, television and magazines predicts black and white adolescents’ sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1018–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Miu A. Does watching sex on television predict teen pregnancy? Findings from a national longitudinal survey of youth. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1047–1054. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Berry SH, Kanouse DE, Kunkel D, Hunter SB, Miu A. Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):280–289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Elliott MN, Miu A. Linking media content to media effects: The RAND television and adolescent sexuality study. In: Jordan AB, Kunkel D, Manganello J, Fishbein M, editors. Media Messages and Public Health. A Decisions Approach to Content Analysis. New York: Routledge; 2009. pp. 154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Creeber G, editor. The television genre book. 2. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Mares ML. Effects of talk show viewing on adolescents. Journal of Communication. 1998;48(3):69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dielman TE. Applied regression analysis: A second course in business and economic statistics. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Thomson Learning; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Desrichard O, Roche S, Begue L. The theory of planned behavior as mediator of the effect of parentalsupervision: A study of intentions to violate driving rules in a representative sample of adolescents. Journal of Safety Research. 2007;38:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MA, Armitage CJ, Baughan CJ. Drivers’ compliance with speed limits: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):964–972. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Hu FB, Siddiqui O, Day LE, Hedeker D, Petraitis J, Richardson J, Sussman S. Differential influence of parental smoking and friends’ smoking on adolescent initiation and escalation of smoking. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994;35(3):248–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M. A reasoned action approach to health promotion. Medical Decision Making. 2008;28(6):834–844. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08326092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. NY: Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter B, Furnham A. Perceptions of television violence: Effects of programme genre and type of violence on viewers’ judgments of violent portrayals. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1984;23:155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1984.tb00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harakeh Z, Scholte RHJ, Vermulst AA, de Vries H, Engels RCME. Parental factors and adolescents’ smoking behavior: An extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Preventative Medicine. 2004;39:951–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Brown L, DiClemente R, Romer D, Valois R, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Salazar L. Differentiating between precursor and control variables when analyzing Reasoned Action theories. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:225–236. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9560-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Validating an index of adolescent sexual behavior using psychosocial theory and social trait correlates. AIDS Behavior. 2008;12:321–331. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9272-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Estimating the longitudinal association between adolescent sexual behavior and exposure to sexual media content. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46(6):586–596. doi: 10.1080/00224490902898736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetsroni A. Three decades of sexual content on prime-time network programming: A longitudinal meta-analytic review. Journal of Communication. 2007;57:318–348. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff T, Greene L, Davis J. National survey of adolescents and young adults: Sexual health knowledge, attitudes and experience. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hull SJ, Hennessy M, Bleakley A, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Identifying the causal pathways from religiosity to delayed adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;48:1–11. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.521868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings-Dozier K. Predicting intentions to obtain a pap smear among African American and Latina women: Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior. Nursing Research. 1999;48(4):198–205. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Antecedents of adolescent initiation of sex, contraceptive use, and pregnancy. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26(2):473–485. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Eyal K, Finnerty K, Biely E, Donnerstein E. Sex on TV 4: A Kaiser Family Foundation Report. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. Getting under your skins. Redding Record Searchlight. 2011 Feb 10; Available at: http://www.redding.com/news/2011/feb/10/ruth-marcus-getting-under-your-145skins/

- Martino SC, Collins RL, Kanouse DE, Elliott M, Berry SH. Social cognitive processes mediating the relationship between exposure to television’s sexual content and adolescents’ sexual behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89(6):914–924. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey R, Zavoina W. A statistical model for the analysis of ordinal level dependent variables. Journal of Mathematical Sociology. 1975;4:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi RL, Moyer-Guse E, Byrne S. All joking aside: A serious investigation into the persuasive effect of funny social issue messages. Communication Monographs. 2007;74(1):29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Neale S. Genre and television. In: Creeber G, editor. The television genre book. 2. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008. pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf KA. The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Paik H, Comstock G. The effects of television violence on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Communication Research. 1994;21(4):516–546. [Google Scholar]

- Pardun CJ, L’Engle KL, Brown JD. Linking exposure to outcomes: Early adolescents’ consumption of sexual content in six media. Mass Communication & Society. 2005;8(2):75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Parents Television Council. PTC calls on Feds to investigate “Skins” on MTV for child pornography and exploitation. 2011 Jan 20; Press release. Available at: http://www.parentstv.org/PTC/news/release/2011/0120.asp.

- Potter WJ, Warren R. Humor as camouflage of televised violence. Journal of Communication. 1998;48:40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K, Hayes A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffe D, Lacy S, Fico FG. Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes RE, Courneya KS, Jones LW. Personality and social cognitive influences on exercise behavior: adding the activity trait to the theory of planned behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2004;5:243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:1–8. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Orr M, Lindberg LD, Diaz DC. Changing behavioral risk for pregnancy among high school students in the United States, 1991–2007. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuker LAE. MTV’s “Skins” loses more advertisers. The Wall Street Journal. 2011 Jan 25; Available at: http://online.wsj.com/

- Sieverding JA, Adler N, Witt S, Ellen J. The influence of parental monitoring on adolescent sexual initiation. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:724–729. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetler B. A racy show with teenagers steps back from a boundary. The New York Times. 2011 Jan 19; Available at: http://nytimes.com/

- [Accessed, 20 November, 2009];Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior. 2001 Jun; from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/sexualhealth/index.html. [PubMed]

- Turner G. Genre, hybridity and Mutation. In: Creeber G, editor. The television genre book. 2. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2008. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Villani S. Impact of media on children and adolescents: A 10-year review of the research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):392–401. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(1):6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DG. The privileged role of the late-night joke: Exploring humor’s role in disrupting argument scrutiny. Media Psychology. 2008;11:119–142. [Google Scholar]