Abstract

Prescriptions written by general practitioners and medical specialists were studied and compared to determine the type, time of onset and clinical importance of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) in an attempt to reduce further complications.

In 2007, 28, 956, 638 prescriptions and 15, 610, 912 prescriptions in 2008 were filled by pharmacies affiliated with medical science universities. These prescriptions, prescribed by physicians from 33 Iranian medical universities nationwide were then evaluated with a prescription processing software named Pardazesh Nosakh. After processing and analyzing the data, DDIs were discovered in 14 different medical specialists consisting of internists, cardiologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, neurosurgeons, general surgeons, infectious diseases, urologists, dermatologists, ENT, ophthalmologists, orthopedists, and pediatrician. The results were then analyzed through methods applied in the book of Drug Interaction Facts.

The results revealed that in 2007-2008, 0.77% of prescriptions had DDIs out of which 0.67% were with significant clinical importance. The percentage of interactions with significant clinical importance was higher in prescriptions of medical specialists and of those, cardiologists and internists ranked top on the list, while dermatologists ranked the lowest. The most common interacting combination prescribed was digoxin and furosmide in 2007-2008, and captopril and triamteren in 2008-2009. Moreover, this study showed that polypharmacy was an important factor which led to DDIs. Drug interactions were common among outpatients prescribed multiple medications and the rate of DDIs increased with the number of drugs prescribed.

It is our opinion that by being up-to-date on drug information and participating in related educational classes and workshops, physicians can increase the chances of choosing the correct drug treatment and hence significantly decrease possible DDIs side effects.

Key Words: Drug-drug interactions, Clinical significant, Polypharmacy, Patient

Introduction

Among medical errors, potentially serious drug-drug interactions (DDIs) have recently received increased attention. Currently available estimates of DDI incidences vary widely depending on the method of defining and finding potential DDIs and the method of defining the population assessed. Published studies have reported proportions of potential DDIs ranging from 2.2% to 30% in hospitalized patients and from 9.2% to 70.3% in ambulatory patients (1-3).

A DDI can be defined as a pharmacological or clinical response to the administration of a drug combination, different from that of anticipated one from the known effects of the two agents when given alone. The clinical result of a DDI may be manifested as antagonism, synergism, or idiosyncratic (4).

The consequences of mistakes and drug errors such as drug interactions affect millions of patients every year and contribute to 5% of patient admissions into hospitals (5-8). These medical errors also increase the patients› expenses, which ultimately affects the whole society (9).

There is little knowledge in terms of the epidemiology of DDIs on the clinical level and most evidence and documentations on this come from case reports, voluntary studies and/or through reports from DDIs detected in admitted hospital patients (10-16).

The treatment of a disease usually requires the use of more than one drug. When patients have multiple symptoms, it becomes necessary to prescribe a number of drugs. In this case, physicians must consider the possibility of DDIs. DDIs mostly occur among drugs with a low therapeutic index having a small difference between their therapeutic and toxic or lethal dose. This means, with the slightest change in the dosage of a drug, it can produce dangerous and harmful effects. The severity of illness in the patient being treated is also another predisposing factor to DDIs, such that treating cardiovascular, collagen vascular, and infectious disease and psychiatric disorders have the greatest potential for dangerous drug interactions.

Drug interactions are one of the most important drug mistakes known and are only predictable and preventable by revision of previous documentations, reports, and clinical studies (8). However, most physicians are unaware of major and clinically important drug interactions (17-21); thus, equipping physicians› clinics with a computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system can warn physicians of impending drug interactions, and should this system be further supervised by pharmacologists, especially focusing on DDIs, this, to a large extent will reduce possible complications and consequences (20, 22, 23).

Experimental

This study was performed using Pardazesh Nosakh, a prescription processing software program, provided by the National Committee of Rational Drug Use. This program was developed for the DOS operating system and Novell Network in 1998. After a pilot run in the Medical University of Mashhad, the application was published for all Iranian Medical universities.

In this cross-sectional study, all data from March 21, 2007 to December 21, 2009 were analyzed. Data of the physicians› prescriptions were collected from 33 different medical science universities nationwide. Available data on prescriptions included physician identification, name, strength, and quantity of the medications dispensed. Due to the greater clinical importance of major DDIs, moderate and minor DDIs were not considered in this study.

From March 21, 2007 to March 20, 2008, 28, 956, 638 prescriptions were gathered. The number of prescriptions from March 21, 2008 to December 20, 2009 (in the spring, summer, and autumn) was 15, 610, 912. After processing and analyzing all of the prescriptions, the total occurrence of DDIs made by all physicians was determined and separated according to general practitioners and medical specialists. Data were from 14 different medical specialists consisting of internists, cardiologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, neurosurgeons, general surgeons, infectious diseases, urologists, dermatologists, ENT, ophthalmologists, orthopedists, and pediatrician. The results were then analyzed by methods that were applied in the book Drug Interaction Facts (DIF) (24). DIF rated DDIs in a five-item summary measure based on the severity and corresponding documentation (probable, suspected, possible, and unlikely) for each drug interaction.

Results and Discussion

This study analyzed 28,956,638 prescriptions from March 21, 2007 to March 20, 2008 and 15, 610, 912 prescriptions from March 21, 2008 to December 20, 2009 from 33 different medical universities in Iran (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 1.

Result of processing and analyzing the total prescriptions

|

2008-2009

|

2007-2008

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | %SI | NP | %MI | Total NP | NP | %SI | NP | %MI | Total NP | |

| 110,837 | 0.71 | 140,498 | 0.90 | 15,610,912 | 194,009 | 0.67 | 222,966 | 0.77 | 28,956,638 | All of physicians |

| 11,990 | 9.01 | 1 2,681 | 9.53 | 133,047 | 25,526 | 7.30 | 27,044 | 7.74 | 349,496 | Cardiologist |

| 60 | 0.04 | 80 | 0.06 | 137,947 | 164 | 0.06 | 217 | 0.07 | 297,314 | Dermatologist |

| 391 | 0.17 | 538 | 0.24 | 228,455 | 663 | 0.12 | 853 | 0.15 | 570,150 | ENT |

| 77,905 | 0.69 | 97,480 | 0.86 | 11,282,948 | 116,067 | 0.50 | 149,599 | 0.74 | 20,292,902 | General practitioners |

| 639 | 0.32 | 833 | 0.42 | 198,365 | 1,819 | 0.36 | 2,294 | 0.46 | 499,681 | General surgeon |

| 1,291 | 0.15 | 1,398 | 0.17 | 845,843 | 95 | 0.07 | 1180 | 0.08 | 1,450,666 | Gynecologist |

| 948 | 0.73 | 1,111 | 0.86 | 129,257 | 1,901 | 0.74 | 2149 | 0.83 | 257,951 | Infectious disease |

| 38,917 | 1.16 | 53,481 | 1.73 | 4,327,964 | 66,766 | 0.96 | 85,273 | 1.30 | 8,663,736 | All of medical specialists |

| 16,795 | 2.16 | 19,761 | 2.54 | 777,710 | 24,295 | 1.82 | 28,634 | 2.14 | 1,338,054 | Internist |

| 2,928 | 1.43 | 6,203 | 3.04 | 204,226 | 3,060 | 0.86 | 4,706 | 1.29 | 365,579 | Neurologist |

| 347 | 0.33 | 614 | 0.59 | 104,429 | 388 | 0.19 | 804 | 0.39 | 206,481 | Neurosurgeon |

| 129 | 0.05 | 165 | 0.07 | 137,947 | 395 | 0.07 | 460 | 0.09 | 535,621 | Ophthalmologist |

| 328 | 0.12 | 492 | 0.18 | 270,933 | 570 | 0.11 | 768 | 0.15 | 500,391 | Orthopedist |

| 815 | 0.11 | 1,011 | 0.13 | 774,807 | 1,862 | 0.11 | 2,158 | 0.13 | 1,695,170 | Pediatrist |

| 1,866 | 1.33 | 4,159 | 2.97 | 139,970 | 4,068 | 1.20 | 8,571 | 2.53 | 338,411 | Psychiatrist |

| 390 | 0.30 | 4,435 | 3.42 | 129,755 | 1,005 | 0.39 | 5,435 | 2.10 | 258,771 | Urologist |

NP: Number of Prescription; SI: Significant Interactions; MI: Major Interactions

Table 3.

Evaluation of prescriptions (Rapid and Delayed Onset in DDIS).

|

2008-2009

|

2007-2008

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no * | %Delayed | no * | %Rapid | no * | %Delayed | no * | %Rapid | All of physicians |

| 1,405,481 | 8.8 | 498,120 | 2.54 | 2,385,690 | 7.51 | 734,601 | 2.16 | |

| 45,629 | 34.3 | 14,417 | 10.84 | 101,331 | 28.99 | 32,822 | 9.39 | Cardiologist |

| 1,382 | 1 | 105 | 0.08 | 2,870 | 0.97 | 421 | 0.14 | Dermatologist |

| 10,181 | 4.46 | 1,163 | 0.51 | 19,876 | 3.49 | 2,435 | 0.43 | ENT |

| 990,502 | 8.78 | 317,847 | 2.82 | 1,527,800 | 7.53 | 499,955 | 2.46 | General practitioners |

| 13,570 | 6.84 | 6,300 | 3.18 | 30,558 | 6.12 | 9,395 | 1.88 | General surgeon |

| 18,798 | 2.22 | 9,232 | 1.09 | 28,610 | 1.97 | 15,731 | 1.08 | Gynecologist |

| 16,007 | 12.38 | 5,233 | 4.05 | 24,622 | 9.55 | 6,184 | 2.4 | Infectious disease |

| 497,652 | 16.09 | 108,637 | 2.74 | 785,614 | 12.57 | 151,502 | 2.06 | All of medical specialists |

| 127,679 | 16.42 | 48,744 | 6.27 | 181,861 | 13.59 | 47,471 | 3.55 | Internist |

| 119,345 | 58.44 | 11,128 | 5.45 | 117,739 | 32.21 | 9,017 | 2.47 | Neurologist |

| 16,866 | 16.15 | 988 | 0.95 | 33,214 | 16.09 | 2,378 | 1.15 | Neurosurgeon |

| 8,600 | 3.4 | 497 | 0.2 | 15,165 | 2.83 | 1,183 | 0.22 | Ophthalmologist |

| 16,766 | 6.19 | 872 | 0.32 | 14,284 | 2.85 | 1,547 | 0.31 | Orthopedist |

| 18,359 | 2.37 | 3,037 | 0.39 | 36,165 | 2.13 | 6,733 | 0.4 | Pediatrist |

| 70,524 | 50.39 | 4,288 | 3.06 | 155,780 | 46.03 | 9,824 | 2.9 | Psychiatrist |

| 13,946 | 10.75 | 2,633 | 2.03 | 23,539 | 9.10 | 6,361 | 2.46 | Urologist |

no*: number of prescriptions

A total of 20, 292, 902 prescriptions in 2007- 2008 and 11, 282, 948 prescriptions in 2008-2009 belonged to general practitioners and 8, 663,736 prescriptions in 2007-2008 and 4, 327, 964 prescriptions in 2008-2009 belonged to medical specialists. The percentage of interactions with significant clinical importance was higher in prescriptions of medical specialists and of those, cardiologists and internists ranked top on the list, while dermatologists ranked the lowest. The mean items per prescriptions (MIP) and percentage of prescriptions with more than four items per prescriptions (% > 4IP) are shown in Table 2. MIP and % > 4IP were highest in the cardiologists, general practitioners, internists and infectious disease specialists in 2007-2008, while MIP and % > 4IP were highest among cardiologists, infectious disease specialists, internists, and neurologists in 2008-2009.

Table 2.

The mean items per prescriptions (M.I.P) and the percentage of prescriptions with more than four items per prescriptions (> 4IP) from -March 21, 2007 to -December 20, 2009

|

2008-2009

|

2007-2008

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % > 4IP | M.I.P | % > 4IP | M.I.P | ||

| 21 | 3.26 | 19 | 3.26 | All of physicians | |

| 37 | 3.67 | 31 | 3.67 | Cardiologist | |

| 3 | 2.06 | 4 | 2.13 | Dermatologist | |

| 13 | 2.89 | 10 | 2.96 | ENT | |

| 24 | 3.41 | 21 | 3.41 | General practitioners | |

| 12 | 2.76 | 11 | 2.85 | General surgeon | |

| 7 | 2.50 | 5 | 2.43 | Gynecologist | |

| 25 | 3.42 | 15 | 3.12 | Infectious disease | |

| 15 | 2.91 | 11 | 2.83 | All of medical specialists | |

| 26 | 3.41 | 19 | 3.23 | Internist | |

| 25 | 3.35 | 13 | 2.93 | Neurologist | |

| 8 | 2.71 | 8 | 2.87 | Neurosurgeon | |

| 13 | 2.89 | 2 | 2.22 | Ophthalmologist | |

| 11 | 2.81 | 7 | 2.67 | Orthopedist | |

| 15 | 2.98 | 11 | 2.94 | Pediatrist | |

| 15 | 2.88 | 14 | 3.03 | Psychiatrist | |

| 8 | 2.35 | 7 | 2.50 | Urologist | |

The percentage of prescriptions with rapid onset interactions was highest among cardiologists. In contrast, the percentage of prescriptions with delayed onset interactions was the highest with psychiatrists in 2007-2008 and the highest in the neurologists in 2008-2009 (Table 3). The list of medications in Table 4 indicated that digoxin and diuretics were commonly associated with DDIs. The most common interacting combination prescribed was digoxin and furosmide in 2007-2008, and captopril and triamteren in 2008-2009 (Tables 5 and 7).

Table 4.

Short list of common interacting medications

| Digoxin |

| Diuretics |

| HMG CoA reductase Inhibitors |

| Allopurinol |

| ACE Is |

| Warfarin |

| Gemfibrozil |

| Haloperidol |

| Amiodarone |

| Clonidine |

Table 5.

Top of 10 DDIs pairs by incidence per 100 prescriptions from March 21, 2007 to march 20, 2009.

| Drug 2 | Drug 1 | % | no * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin | Furosmide | 0.11 | 74,084 |

| Captopril | Triamterene-H | 0.09 | 67,619 |

| Gemfibrozil | Atrovastatin | 0.08 | 65,103 |

| Haloperidol | Propranolol | 0.04 | 26,789 |

| Amitriptyline | Clonidine | 0.03 | 20,666 |

| Doxycycline | Penicilline G | 0.01 | 8,526 |

| Chlorpromazine | Propranolol | 0.01 | 8,049 |

| Propranolol | Verapamil | 0.009 | 6,904 |

| Amiodaron | Digoxin | 0.008 | 6,417 |

| Azithromycine | Atrovastatin | 0.007 | 5,727 |

no*: number of prescriptions

Table 7.

The results of investigation of major DDIS from march 21, 2007 to December 20, 2009

| Documentation | Total of prescriptions | no 2 * | no 1 * | Onset | Significance | Severity | Drug 2 | Drug 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| probable | 74,084 | 29,901 | 44,183 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Furosemide | Digoxin |

| probable | 64,063 | 24,406 | 39,657 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Triamterene | Captopril |

| suspected | 65,083 | 29,543 | 35,540 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Atorvastatin | Gemfibrozil |

| probable | 59,640 | 27,962 | 31,678 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Triamterene | Enalapril |

| possible | 39,497 | 14,650 | 24,847 | Rapid | 4 | Major | Codeine | Cimetidine |

| suspected | 38,075 | 14,369 | 23,706 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Lovastatin | Gemfibrozil |

| possible | 26,789 | 11,679 | 15,110 | Rapid | 4 | Major | Propranolol | Haloperidol |

| unlikely | 25,205 | 11,198 | 14,007 | Delayed | 5 | Major | Hydrochlorothiazide | Allopurinol |

| probable | 21,706 | 7,919 | 13,787 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Spironolactone | Captopril |

| probable | 20,666 | 9,040 | 11,626 | Rapid | 1 | Major | Clonidine | Amitriptyline |

| probable | 11,586 | 4,703 | 6,883 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Hydrochlorothiazide | Digoxin |

| possible | 9,756 | 3,729 | 6,027 | Rapid | 4 | Major | Fluoxetine | Metoclopramide |

| suspected | 8,526 | 2,906 | 5,620 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Penicillin G | Doxycycline |

| probable | 8,326 | 3,237 | 5,089 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Spironolactone | Enalapril |

| probable | 8,049 | 3,008 | 5,041 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Propranolol | Chlorpromazine |

| suspected | 7,365 | 2,621 | 4,744 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Simvastatin | Gemfibrozil |

| probable | 6,904 | 2,509 | 4,395 | Rapid | 1 | Major | Verapamil | Propranolol |

| probable | 6,417 | 2,372 | 4,045 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Digoxin | Amiodarone |

| probable | 7,818 | 4,004 | 3,814 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Atorvastatin | Azithromycin |

| suspected | 5,991 | 2,396 | 3,595 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Nortriptyline | Cisapride |

| suspected | 6,717 | 3,488 | 3,229 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Sulfasalazine | Methotrexate |

| possible | 4,651 | 1,548 | 3,103 | Rapid | 4 | Major | Trazodone | Fluoxetine |

| suspected | 4,596 | 1,656 | 2,940 | Delayed | 2 | Major | Warfarin | Penicillin G |

| possible | 4,219 | 1,427 | 2,792 | Delayed | 4 | Major | Captopril | Allopurinol |

| probable | 4,620 | 1,913 | 2,707 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Lovastatin | Azithromycin |

| probable | 4,107 | 1,448 | 2,659 | Rapid | 1 | Major | Verapamil | Atenolol |

| possible | 5,395 | 2,764 | 2,631 | Rapid | 4 | Major | Omeprazole | Methotrexate |

| suspected | 7,266 | 4,929 | 2,237 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Naproxen | Methotrexate |

| suspected | 3,352 | 1,239 | 2,113 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Trifluoperazine | Cisapride |

| suspected | 3,510 | 1,410 | 2,100 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Propranolol | Clonidine |

| established | 3,471 | 1,450 | 2,021 | Delayed | 1 | Major | Warfarin | Aspirin |

no1*: Number of prescriptions with the major DDIs from March 21, 2007 to march 20, 2008; no2*: Number of prescriptions with the major DDIs from March 21, 2007 to December 20, 2009

Our findings also revealed the most alarming DDIs in prescriptions from March 21, 2007 to December 20, 2009 with significant clinical importance by incidence per 100 prescriptions as shown in Table 5.

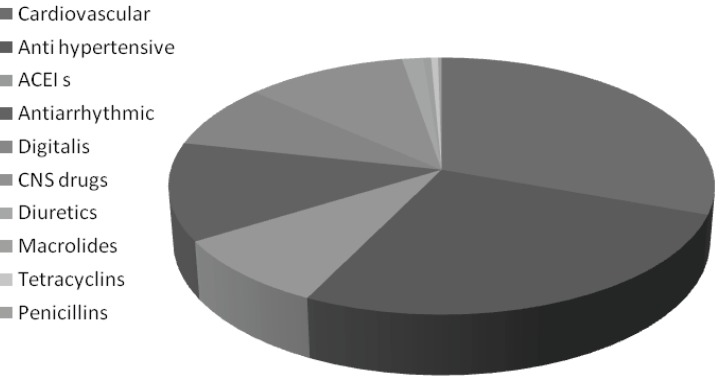

The study of DDIs in the present population showed that the highest DDIs with clinical importance were the antihypertensive drugs such as beta blockers, calcium channel blockers followed by ACE-Is (Table 6).

Table 6.

Abundance of drug categories in the drug interactions

| %Incidence per total of prescriptions | drug categories |

|---|---|

| 85 | Cardiovascular |

| 74 | Anti hypertensive |

| 24.78 | ACEI s |

| 34.44 | Antiarrhythmic |

| 22.63 | Digitalis |

| 30.08 | CNS drugs |

| 4 | Diuretics |

| 1 | Macrolides |

| 1 | Tetracyclins |

| 1 | Penicillins |

Based on these results, the increase in DDIs in the prescriptions occurs when number of items per prescription increased, which led to a rise in the index of DDIs with clinical significance.

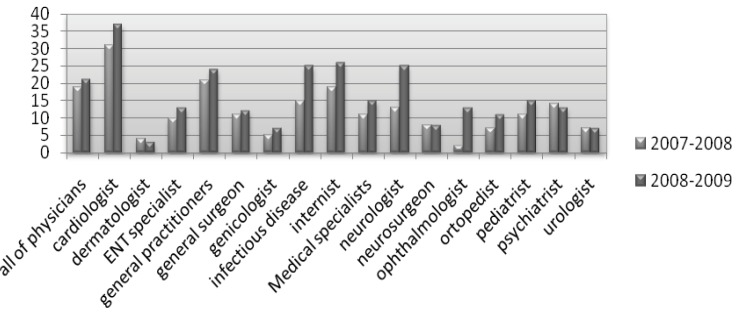

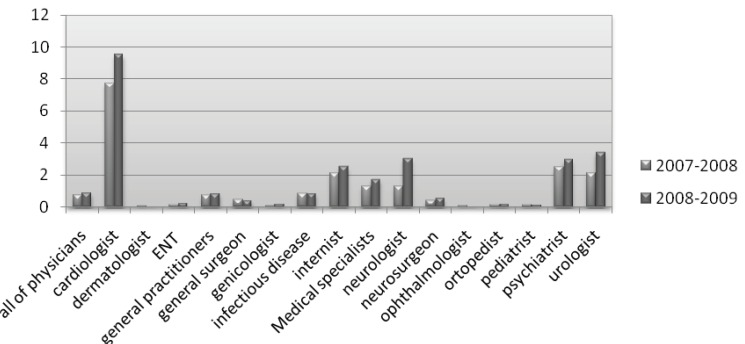

This study revealed that with the increase of percentage in prescriptions with more than four items per prescription in the years 2008-2009, as compared to 2007-2008 (Figure 1), significant major DDIs in the prescriptions of all physicians, general practitioners, and medical specialists in 14 different fields significantly increased. (Figure 2) This was clearly visible in the prescriptions of cardiologists, internists, General practitioners, infectious disease specialists and neurologists who had a greater number of items per prescription.

Figure 1.

The percentage of prescriptions with more than four items per prescription in the years 2008-2009 as compared to 2007-2008

Figure 2.

Major drug interactions in the prescriptions of all physicians in the years 2008-2009 as compared to 2007-2008

Polypharmacy is an important factor which leads to DDIs; however, the more the number of items per prescriptions, the more the likelihood of DDI’s occurance. Straubhaar et al. (25) reported in a study at the University Hospital Basel that hospitalization of patients with heart failure resulted in an increase in the number of drugs prescribed per patient and, thereby, also in the number of potentially interacting drug combinations per patient. During the hospital stay, close medical monitoring combined with continuous nursing and therapeutic care is generally guaranteed, but this may profoundly change after discharge. The elderly generally have several concurrent diseases (26) and consequently, the number of drugs used to treat them is greater, and the greater the number of drugs, the higher the possibility of DDIs. Malone et al. (27), using the prescription database of a North American insurance company with 46 million clients, carried out a retrospective study of the prevalence of 25 clinically relevant interactions. They found that their clients of 70 years or more made up to 7.1% of the total population, but they suffered from 44.8% of all DDIs.

In three past studies on primary care, the rates of potential DDIs for patients receiving two or more drugs were 24.3%, 29.5%, and 42.0%, respectively (28, 39). Another study reported 2.2% of prescriptions with adverse interacting drugs in relation to all prescriptions (30, 31).

In another study, all drug pairs concurrently prescribed to 9481 adults aged 50 to 75 years were evaluated in a health-screening examination. More than 52% of the patients received a combination therapy of drug pairs and 881 (6.4%) were identified as interacting. Of these 881 interactions, 132 (15.0%) were of major severity and 101 of 132 (76.5%) were considered manageable. Only 31 (23.5%) of 132 major interactions (3.5% of all interacting pairs) offered no management options and should thus have been avoided (32). The results of this study and past studies, especially on DDIs in Iran when compared to the present, showed that its percentage is rising and continues to pose problems (33-36).

In primary health care, 9-70% of patients are reported to be exposed to drugs with the risk of a drug interaction, with 1-23% of major significance (37-42). A French study reports an incidence of 27 per 10,000 prescriptions with contraindicated DDIs in an ambulatory outpatient population (43). During hospital admission, the number of DDIs per patient increased with potential clinically relevant DDIs occurring in 1 out of 70 prescriptions (44-47). In another study, 22 potential DDIs of clinical relevance and 65 of ‘possible’ clinical relevance per 100 outpatients per year were recorded. Reported incidences in outpatients ranged from 9.2% to 70.3% for DDIs of any severity and from 1.2% to 23.3% for those considered of major significance (31, 1, 48-51).

In addition, Chen et al. (52) found an incidence of 1.9 per 1000 patient (95% confidence interval 1.5, 2.3) of prescribed potentially hazardous/contraindicated DDIs. They identified multiple possible causes (e.g., lack of knowledge of the DDIs or of the patient medication history) and system failures (e.g., incomplete medication records, lack of communication between primary and secondary care or between the prescriber and the patient) for the dispensing of contraindicated drug combinations.

Unfortunately, there are little supportive data on the incidence of potential DDIs in other large ambulatory populations. Few published studies have determined such errors exclusively, with most aggregating various types of potential medication errors.

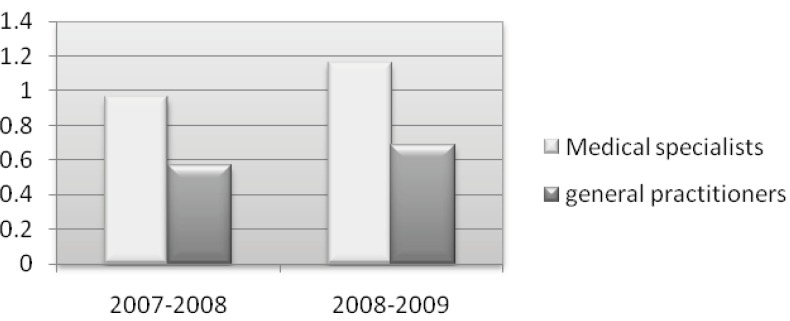

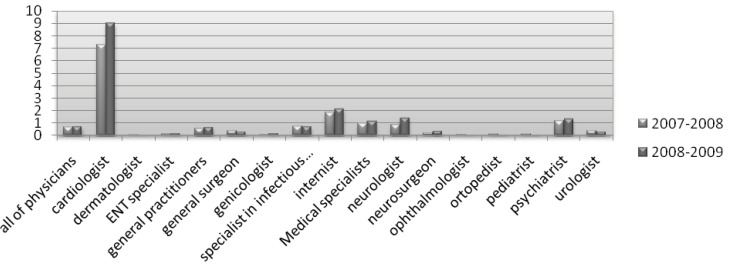

Quite frequently, the determination of medication errors found in studies has been part of a planned intervention that might include medication selection or dosage assessment (53-55), laboratory monitoring (54-56), or inappropriate prescribing (56, 59). Moreover, most studies on medication errors have involved interventions in hospitalized or with institutionalized patients, but not with outpatients (54, 56, 60-64). In the year 1988, Dumbro et al. (28) reported that out of the total number of DDIs they had discovered, 17% were of great significance, while in our study, we found major DDIs with significant clinical importance as shown in Table 2. Comparing general practitioners and medical specialists, it is evident that from March 21, 2007 to December 20, 2009, more alarming DDIs were found in the prescriptions of medical specialists (Figure 3). The same observation was made when we compared the prescriptions resulting in major DDIs of clinical importance (Figure 4). It seems that medical specialists deal more with potent drugs with a low therapeutic index that might be a cause of more DDIs in their prescriptions.

Figure 3.

Major drug interactions with significant clinical importance in the prescriptions of general and specialist practitioners

Figure 4.

Major drug interactions with significant clinical importance in the prescriptions of all physicians in the years 2008-2009 as compared to 2007-2008

Figure 5.

Abundance of drug categories in the DDIs

The results of our study also revealed that the most common drugs associated with major interactions of significant clinical importance were those prescribed by cardiologists. Previous studies have also shown that prescriptions of cardiologists had the highest rate of DDIs (65). With regard to the interactions detected, other studies without intervention by pharmacists found more DDIs in the fields of cardiology (27.9%), hematology (23.4%), neurology (2.7%), psychiatry (5.3%), and gastroenterology (5.1%). In addition, 151 DDIs were detected during the three-month follow-up period. The interactions found most frequently were: digoxin-furosemide, furosemid-corticoid, AAS-low molecular weight heparin, amiodarone-furosemide, omeprazole-diazepam, phenytoin-corticoid and AAS-oral antidiabetics (65, 66), while in our study, we found that the most common interacting combination prescribed were: digoxin-furosmide, captopril-plustriamteren, gemfibrozil-atorvastatin, enalapril-triamteren, cimetidine-codeine, gemfibrozil-lovastatin, and haloperidol-propranolol.

Shivo et al. (67) in the year 2000 carried out a study in Finland that showed harmful interactions between over the counter (OTC) drugs (especially NSAIDs and analgesics) and prescription drugs. This shows that DDIs do not solely occur with prescription drugs, but food and other OTC drugs purchased and consumed by patients also play a role and could sometimes be responsible for treatment failure.

Conclusions

Potential drug interactions are frequent among outpatients prescribed multiple medications and the rate is directly related to the number of drugs prescribed. It is our opinion that physicians must pay closer attention to DDIs, especially cardiovascular, antihypertensive, ACEIs, antiarrhythmic, digitalis, and CNS drugs and diuretics and the DDIs between OTC drugs and prescription drugs, especially in terms of side effects and the economic burden that they may produce. Moreover, adhering to the correct policies of writing prescriptions, being up-to-date on drug information, and participating in related educational classes and workshops by physicians, may significantly increase the chances of the appropriate drug being selected for treatment and hence quicker patient recovery .

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the National Committee of Rational Drug Use and the RUD committees of the universities for collecting the data used in this study. The assistance of Dr. Nasrin Khoshnevis, Ahmadali Mostoufi, Dr. Nooshin Mohammad Hoseini, Dr. Arash Tehrani Banihashemi and Alireza Yari for data collection is also highly appreciated.

References

- 1.Jankel CA, Speedie SM. Detecting drug interactions: a review of the literature. DICP. 1990;24:982–89. doi: 10.1177/106002809002401014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jankel CA, Fitterman LK. Epidemiology of drug-drug interactions as a cause of hospital admissions. Drug Saf. 1993;9:51–59. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199309010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajebi G, Mortazavi SA. An Investigation of drug interactions in hospital pharmacy prescriptions. Iranian J. Pharm. Res. 2002;1:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatro DS, editor. Drug Interaction Facts. St. Louis, MO: Facts and Comparisons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta- analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1200–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elinarson TR. Drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:832–840. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbasi Nazari M, Khanzadeh Moqhadam N. Evaluation of pharmacokinetic drug interactions in prescriptions of intensive care unit (ICU) in a teaching hospital. Iranian J. Pharm. Res. 2006;5:215–218. [Google Scholar]

- 8.David N, Juurlink Mamdani M, Kopp A, Laupacis A. Drug-Drug interactions Among Elderly Patients hospitalized for drug toxicity, JAMA. 2003;289:1652–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha AK, Kuperman GJ, Rittenberg E, Teich JM, Bates DW. Identifying hospital admissions due to adverse drug events using a computer- based monitor. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug saf. 2001;10:113–119. doi: 10.1002/pds.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro LE, Shear NH. Drug- drug interactions: how scared should we be? CMAJ. 1999;161:1266–1267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson JE, Bates DW. Preventable medication errors: identifying and eliminating serious drug interactions. J AM Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41:159–160. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansten PD, Horn JR, Hazlet TK. ORCA: OpeRational Classific Action of drug interactions. J AM Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study. N Engl Med. 1991;324:377–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention: ADE prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1995;274:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halkin H, Katzir I, Kurman I, Jan J, Malkin BB. Preventing drug interactions by online prescription screening in community pharmacies and medical practices. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:260–265. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.114228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catherine C Peng, Peter A Glassman, Iny R Marks, Curtis Fowler, Brenda Castiglione, Chester B Good. Retrospective Drug Utilization Review: Incidence of Clinically Relevant Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in a Large Ambulatory Population. Journal of managed care pharmacy (JMCP) 2003;9:513–522. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaoul R, Shahory R, Tamir A, Jaffe M. Comparison between pediatricians and family practitioners in the use of the prokinetic cisapride for gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1118–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langdorf MI, Fox JC, Marwah RS, Montague BJ, Hart MM. Physician versus computer knowledge of potential drug interactions in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1321–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weideman RA, Bernstein IH, Mckinney WP. Pharmacist recognition of potential drug interactions. Amj Health Syst Pharm. 1999:1524–1529. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.15.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavuto NJ, Woosley RL, Sale M. Pharmacies and prevention of potentially fatal drug interactions. JAMA. 1996;275:1086–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glassman PA, Simon B, Belperio P, Lanto A. Improving recognition of drug interactions: benefits and barriers to using automated drug alerts. Med Care. 2002;40:1161–1171. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hazlet TK, Lee TA, Hansten PD, Horn JR. Performance of community pharmacy drug interaction software. J AM Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41:200–204. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Del Fiol G, Rocha BH, Kuperman GJ, Bates DW, Nohama P. Comparison of two knowledge bases on the detection of drug- drug interactions. Proc AMIA Symp. 2000:171–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatro DS, editor. Drug Interaction Facts. St. Louis, MO: Facts and Comparisons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straubhaar B, Krähenbühl S, Schlienger RG. The prevalence of potential drug-drug interactions in patients with heart failure at hospital discharge. Drug Saf. 2006;29:79–90. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger T, Dormann H, Ahne G, Runge U, Azaz-Livshits T, Neubert A. Identification of adverse drug reactions in geriatric inpatients using a computerised drug database. Drugs Aging. 2003;20:769–76. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200320100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malone DC, Hutchins DS, Haupert H, Hansten P, Duncan B, Van Berger RC. Assessment of potential drug-drug interactions with a prescription claims database. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1983–91. doi: 10.2146/ajhp040567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dambro MR, Kallgren MA. Drug interactions in a clinic using COSTAR. Comput. Biol. Med. 1988;18:31–8. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(88)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurfees JF, Dotson RL. Drug interactions in the elderly. J. Fam. Pract. 1987;25:477–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gosney M, Tallis R. Prescription of contraindicated and interacting drugs in elderly patients admitted to hospital. Lancet. 1984;8:564–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linnarsson R. Drug interactions in primary health care. A retrospective database study and its implications for the design of a computerized decision support system. Scand J. Prim Health Care. 1993;11:181–6. doi: 10.3109/02813439308994827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergk V, Gasse C, Rothenbacher D, Loew M, Brenner H, Haefeli WE. Drug interactions in primary care: impact of a new algorithm on risk determination. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;76:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ansari KU, Singh S, Pandey RC. Evaluation of prescribing pattern of doctors for rational drug therapy. Indian J Pharmacol. 1998;30:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jahangiri Bijan, Delfan Aziz, Fahimi Fanak. The Study of 5100 Prescriptions in Tehran. Nabz. 1375;5:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mortaza-Semnani K, Saeidi M, Qaripour M. The study of drug interactions of cardiovascular drugs on insurance prescriptions of shahre sari›s drug stores in the years 1378-1379. Research Medical Article of the University of Medicine, Mazandaran. 1380;32:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karami Narges. The Study of Outpatient Prescriptions for the Effects of Drug Interactions. Doctorate Thesis of Pharmacology. Tehran: Pharmacology Department of the University of Medical Sciences; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bjerrum L, Andersen M, Petersen G. Exposure to potential drug interactions in primary health care. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2003;21:153–8. doi: 10.1080/02813430310001806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jankel CA, Speedie S. Detecting drug interactions: a review of the literature. Ann. Pharmacother. 1990;24:982–9. doi: 10.1177/106002809002401014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Björkman IK, Fastbom J, Schmidt IK. The Pharmaceutical Care of the Elderly in Europe Research (PEER) Group. Drug-drug interactions in the elderly. Ann. Pharmacother. 2002;36:1675–81. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergendal L, Friberg A, Schaffrath A. Potential drug-drug interactions in 5,125 mostly elderly out-patients in Gothenburg, Sweden. Pharm World Sci. 1995;17:152–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01879709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa AJ. Potential drug interactions in an ambulatory geriatric population. Fam. Pract. 1991;8:234–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/8.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosholm JU, Bjerrum L, Hallas J. Polypharmacy and the risk of drug-drug interactions among Danish elderly. Dan. Med. Bull. 1998;45:210–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guédon-Moreau L, Ducrocq D, Duc MF. Absolute contraindications in relation to potential drug interactions in outpatient prescriptions: analysis of the first five million prescriptions in 1999. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003;59:689–95. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0684-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Köhler GI, Bode-Böger SM, Busse R. Drug-drug interactions in medical patients: effects of in-hospital treatment and relation to multiple drug use. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;38:504–13. doi: 10.5414/cpp38504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grönroos PE, Irjala KM, Huupponen RK. A medication database--a tool for detecting drug interactions in hospital. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:13–7. doi: 10.1007/s002280050330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glintborg B, Andersen SE, Dalhoff K. Drug-drug interactions among recently hospitalized patients-frequent but mostly clinically insignificant. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(9):675–681. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0978-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cruciol-Souza JM, Thomson JC. Prevalence of potential drug-drug interactions and its associated factors in a Brazilian teaching hospital. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9(3):427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bjorkman IK, Fastbom J, Schmidt IK, Bernsten CB. Drug-drug interactions in the elderly. Ann Pharmacotherapy. 2002;36:1675–81. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Costa AJ. Potential drug interactions in an ambulatory geriatric population. Fam. Pract. 1991;8:234–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/8.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergendal L, Friberg A, Schaffrath A. Potential drug--drug interactions in 5,125 mostly elderly out-patients in Gothenburg, Sweden. Pharm. World Sci. 1995;17:152–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01879709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bjerrum L, Andersen M, Petersen G, Kragstrup J. Exposure to potential drug interactions in primary health care. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2003;21:153–8. doi: 10.1080/02813430310001806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen YF, Avery AJ, Neil KE, Johnson C, Dewey ME, Stockley IH. Incidence and possible causes of prescribing potentially hazardous/contraindicated drug combinations in general practice. Drug Saf. 2005;28:67–80. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teich JM, Merchia PR, Schmiz JL, Kuperman GJ, Spurr CD, Bates DW. Effects of computerized physician order entry on prescribing practices. Arch Inter Med. 2000;160:2741–47. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Falconnier AD, Haefeli WE, Schoenenberger RA, Surber C, Martin- Facklam M. Drug dosage in patients with renal failure optimized by immediate concurrent feedback. J. Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:369–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016006369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barker KN, Flynn EA, Pepper GA, Bates DW, Mikeal RL. Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002;162:1897–1903. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raschke RA, Gollihare B, Wunderlich TA. A computer alert system to prevent injury from adverse drug events: development and evaluation in a community teaching hospital. JAMA. 1998;280:1317–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schiff GD, Aggarwal HC, Kumar S, McNutt RA. Prescribing potassium despite hyperkalemia: medication errors uncovered by linking laboratory and pharmacy information systems. Am. J. Med. 2000;109:494–97. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galanter WL, Didomenico R, Polikaitis A. Analysis of medication safety alerts for inpatient digoxin use with computerized physician order entry. J. Gen Intern. Med. 2002;17 doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monane M, Matthias DM, Nagle BA, Kelly MA. Improving prescribing patterns for the elderly through an online drug utilization review intervention: a system linking the physician, pharmacist and computer. JAMA. 1998;280:1249–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lesar TS, Briceland L, Stein DS. Factors related to errors in medication prescribing. JAMA. 1997;277:312–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA. 1998;280:1311–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuperman GJ, Bates DW, Teich JM, Schneider JR, Cheiman D. A new knowledge structure for drug-drug interactions. Proc Annu Symp. Comput. Appl. Med. Care. 1994:836–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 1999;282:267–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson JF, Kuperman GJ, Shek C, Bates DW. Physician responses to lifethreatening drug-drug interaction alerts. J. Gen Intern. Med. 2001;16 [Google Scholar]

- 65.J Peral Aguirregoitia, U Lertxundi Etxebarria, M J Martínez Bengoechea, O Mora Atorrasagasti, E Franco Lamela and I Gabilondo Zelaia, Prospective assessment of drug interactions in hospitalized patients using a computer programme, Farm. Hosp. 2007;31:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s1130-6343(07)75719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dambro MR, Kallgren MA. Drug interaction in a clinic using Costar. Comput Biol. Med. 1988;18:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(88)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sihvo S, Klaukka T, Martikainen J. Frequency of daily over-the-counter drug use and potential clinically significant over-the-counter-prescription drug interactions in the Finnish adult population. Eur J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000;56:496–799. doi: 10.1007/s002280000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]