Abstract

Objective To determine the effects of a policy of “use acupuncture” on headache, health status, days off sick, and use of resources in patients with chronic headache compared with a policy of “avoid acupuncture.”

Design Randomised, controlled trial.

Setting General practices in England and Wales.

Participants 401 patients with chronic headache, predominantly migraine.

Interventions Patients were randomly allocated to receive up to 12 acupuncture treatments over three months or to a control intervention offering usual care.

Main outcome measures Headache score, SF-36 health status, and use of medication were assessed at baseline, three, and 12 months. Use of resources was assessed every three months.

Results Headache score at 12 months, the primary end point, was lower in the acupuncture group (16.2, SD 13.7, n = 161, 34% reduction from baseline) than in controls (22.3, SD 17.0, n = 140, 16% reduction from baseline). The adjusted difference between means is 4.6 (95% confidence interval 2.2 to 7.0; P = 0.0002). This result is robust to sensitivity analysis incorporating imputation for missing data. Patients in the acupuncture group experienced the equivalent of 22 fewer days of headache per year (8 to 38). SF-36 data favoured acupuncture, although differences reached significance only for physical role functioning, energy, and change in health. Compared with controls, patients randomised to acupuncture used 15% less medication (P = 0.02), made 25% fewer visits to general practitioners (P = 0.10), and took 15% fewer days off sick (P = 0.2).

Conclusions Acupuncture leads to persisting, clinically relevant benefits for primary care patients with chronic headache, particularly migraine. Expansion of NHS acupuncture services should be considered.

Introduction

Migraine and tension-type headache give rise to notable health,1,2 economic,2 and social costs.2,3 Despite the undoubted benefits of medication,4 many patients continue to experience distress and social disruption. This leads patients to try, and health professionals to recommend, non-pharmacological approaches to headache care. One of the most popular approaches seems to be acupuncture. Each week 10% of general practitioners in England either refer patients to acupuncture or practise it themselves,5 and chronic headache is one of the most commonly treated conditions.6

A recent Cochrane review of 26 randomised trials of acupuncture for headache concluded that, although existing evidence supports the value of acupuncture, the quality and amount of evidence are not fully convincing.7 The review identifies an urgent need for well planned, large scale studies to assess the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of acupuncture under “real” conditions. In 1998 the NHS National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment commissioned us to conduct such a trial (trial number ISRCTN96537534). Our aim was to estimate the effects of acupuncture in practice8: we established an acupuncture service in primary care; we then sought to determine the effects of a policy of “use acupuncture” on headache, health status, days off sick, and use of resources in patients with chronic headache compared with a policy of “avoid acupuncture.” This reflects two real decisions: that made by general practitioners when managing the care of headache patients and that made by NHS entities when commissioning health services.

Methods

The protocol and recruitment methods have been published previously.9,10 The study included 12 separate sites consisting of a single acupuncture practice and two to five local general practices. Study sites were located in Merseyside, London and surrounding counties, Wales, and the north and south west of England.

Accrual of patients

Practices searched their databases to identify potential participants. General practitioners then sent letters to suitable patients, providing information about the trial. A researcher at the study centre conducted recruitment interviews, eligibility screening, and baseline assessment by telephone. Patients' conditions were diagnosed as migraine or tension-type headache, following criteria of the International Headache Society (IHS).11 Patients aged 18-65 and who reported an average of at least two headaches per month were eligible. Patients were excluded for any of the following: onset of headache disorder less than one year before or at age 50 or older; pregnancy; malignancy; cluster headache (IHS code 3); suspicion that headache disorder had specific aetiology (IHS code 5-11); cranial neuralgias (IHS code 12); and acupuncture treatment in the previous 12 months. Eligible patients completed a baseline headache diary for four weeks. Patients who provided written informed consent, had a mean weekly baseline headache score of 8.75 or more, and completed at least 75% of the baseline diary were randomised to a policy of “use acupuncture” or “avoid acupuncture.” Given a power of 90% and an α of 5%, we estimated that we would require 288 evaluable patients to detect a reduction in headache score of 35% in the acupuncture group, compared with 20% in controls. We assumed a dropout rate of about 25% and planned to randomise 400 patients.

Randomisation

We used randomised minimisation (“biased coin”) to allocate patients. The minimised variables were age, sex, diagnosis (migraine or tension-type), headache score at baseline, number of years of headache disorder (chronicity), and number of patients already allocated to each group, averaged separately by site. We used a secure, password protected database to implement randomisation, which was thus fully concealed.

Treatment

Patients randomised to acupuncture received, in addition to standard care from general practitioners, up to 12 treatments over three months from an advanced member of the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists. All acupuncturists in the study had completed a minimum of 250 hours of postgraduate training in acupuncture, which included the theory and practice of traditional Chinese medicine; they had practised acupuncture for a median of 12 years and treated a median of 22 patients per week. The acupuncture point prescriptions used were individualised to each patient and were at the discretion of the acupuncturist. Patients randomised to “avoid acupuncture” received usual care from their general practitioner but were not referred to acupuncture.

Outcome assessment

Patients completed a daily diary of headache and medication use for four weeks at baseline and then three months and one year after randomisation. Severity of headache was recorded four times a day on a six point Likert scale (box) and the total summed to give a headache score. The SF-36 health status questionnaire was completed at baseline, three months, and one year. Every three months after randomisation, patients completed additional questionnaires that monitored use of headache treatments and days sick from work or other usual activity. While the study was under way we added an additional end point: we contacted patients one year after randomisation and asked them to give a global estimate of current and baseline headache severity on a 0-10 scale. This enabled us to obtain data from patients who were unwilling to complete diaries, for use in sensitivity analysis.

Statistical considerations

The primary outcome measure was headache score at the one year follow up. Secondary outcome measures included headache score at three months, days with headache, use of medication scored with the medication quantification scale (MQS),12,13 the SF-36, use of resources, and days off usual activities. We revised the statistical plan to employ adjusted rather than unadjusted analyses after publication of the initial protocol but before we conducted any analyses. We analysed our data on Stata 8 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) using ANCOVA for continuous end points, χ2 for binary data, and negative binomial regression for count data such as number of days of sick leave. We entered minimisation variables into regression models as covariates. We analysed data according to allocation, regardless of the treatment received. We conducted sensitivity analyses to examine the possible effect of missing data (see appendix on bmj.com).

Likert scale of headache severity

0: no headache

1: I notice the headache only when I pay attention to it

2: Mild headache that can be ignored at times

3: Headache is painful, but I can do my job or usual tasks

4: Very severe headache; I find it difficult to concentrate and can do only undemanding tasks

5: Intense, incapacitating headache

Results

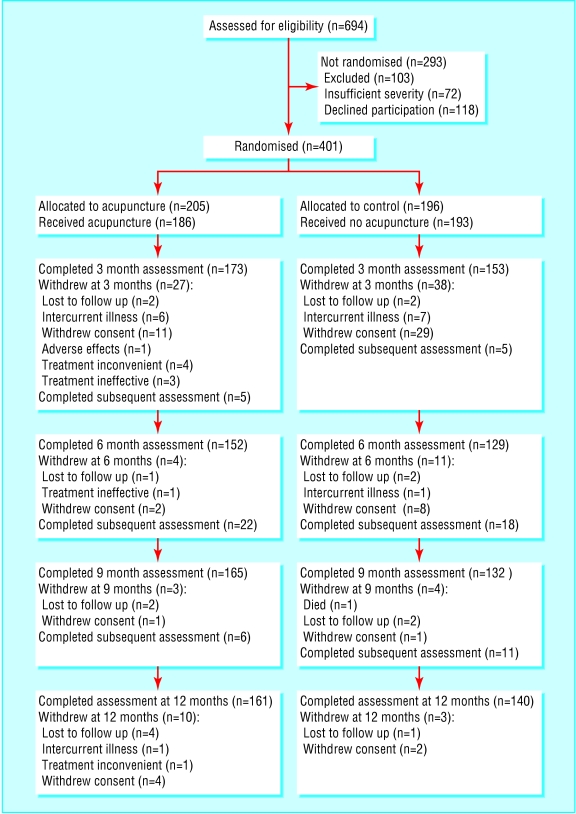

Recruitment took place between November 1999 and January 2001. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the trial. Compliance of patients was good: only three patients in the control group reported receiving acupuncture outside the study. Acupuncture patients received a median of nine (interquartile range 6-11) treatments, with a median of one treatment per week. The dropout rate was close to that expected and approximately balanced between groups. Patients who dropped out were similar to completers in terms of sex, diagnosis, and chronicity, but they were slightly younger (43 v 46 years, P = 0.01) and had higher headache score at baseline (29.3 v. 25.6, P = 0.04). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics by group for the 301 patients who completed the trial: the groups are highly comparable. Thirty one of the patients who withdrew provided three month data, and an additional 45 provided a global assessment. Only 6% of patients (12 in each group) provided no data for headache after randomisation.

Fig 1.

Flow of participants through the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages) of participants unless otherwise indicated

| Acupuncture (n=161) | Control (n=140) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) |

46.4 (10.0) |

46.2 (10.8) |

| Female |

133 (83) |

120 (86) |

| Migraine diagnosis |

152 (94) |

132 (94) |

| Tension-type headache |

9 (6) |

8 (6) |

| Mean chronicity in years (SD) | 21.3 (14.5) | 21.9 (13.3) |

Table 2 shows results for medical outcomes for patients completing 12 month follow up. In the primary analysis mean headache scores were significantly lower in the acupuncture group. Scores fell by 34% in the acupuncture group compared with 16% in controls (P = 0.0002). This result was highly robust to sensitivity analysis for missing data (smallest difference between groups of 3.85, P = 0.002; see appendix on bmj.com). When we used the prespecified cut-off point of 35% as a clinically significant reduction in headache score, 22% more acupuncture patients improved than controls, equivalent to a number needed to treat of 4.6 (95% confidence interval 9.1 to 3.0). The difference in days with headache of 1.8 days per four weeks is equivalent to 22 fewer days of headache per year (8 to 38). The effects of acupuncture seem to be long lasting; although few patients continued to receive acupuncture after the initial three month treatment period (25, 10, and 6 patients received treatment after 3, 6, and 9, months, respectively), headache scores were lower at 12 months than at the follow up after treatment. Medication scores at follow up were lower in the acupuncture group, although differences between groups did not reach significance for all end points. In an unplanned analysis we summed and scaled all medication taken by patients after randomisation and compared groups with adjustment for baseline scores. Use of medication use fell by 23% in controls but by 37% in the acupuncture group (adjusted difference between groups 15%; 95% confidence interval 3%, 27%; P = 0.01). SF-36 data generally favoured acupuncture (table 3), although differences reached significance only for physical role functioning, energy, and change in health.

Table 2.

Headache and medication outcomes. Higher scores indicate greater severity of headache and increased use of medication. Differences between groups are calculated by analysis of covariance. Values are means (SD) unless otherwise indicated

|

Baseline |

After treatment (at three months after randomisation) |

At 12 months |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End point | Acupuncture (n=161) | Controls (n=140) | Acupuncture (n=159) | Controls (n=136) | Difference‡ | 95% CI | P value | Acupuncture (n=161) | Controls (n=140) | Difference‡ | 95% CI | P value |

| Weekly headache score |

24.6 (14.1) |

26.7 (16.8) |

18.0 (14.8) |

23.7 (16.8) |

3.9 |

1.6 to 6.3 |

0.001 |

16.2 (13.7) |

22.3 (17.0) |

4.6 |

2.2 to 7.0 |

0.0002 |

| Days of headache in 28 days |

15.6 (6.6) |

16.2 (6.7) |

12.1 (7.2) |

14.3 (7.3) |

1.8 |

0.7 to 2.9 |

0.002 |

11.4 (7.5) |

13.6 (7.5) |

1.8 |

0.6 to 2.9 |

0.003 |

| Clinically relevant improvement in score* |

— |

— |

65 (41%) |

37 (27%) |

14% |

3% to 24% |

0.014 |

87 (54%) |

45 (32%) |

22% |

11% to 33% |

0.0001 |

| Clinically relevant improvement in frequency† |

— |

— |

36 (23%) |

17 (13%) |

10% |

2% to 19% |

0.024 |

49 (30%) |

21 (15%) |

15% |

6% to 25% |

0.002 |

| Scaled pain medication (weekly) |

16.5 (18.1) |

14.3 (17.6) |

11.0 (13.6) |

11.4 (14.1) |

1.6 |

−0.7 to 3.9 |

0.16 |

8.5 (12.2) |

8.7 (12.6) |

1.2 |

−0.6 to 3.1 |

0.19 |

| Scaled prophylactic medication (weekly) |

9.0 (17.8) |

13.3 (22.2) |

7.9 (17.6) |

11.5 (21.3) |

0.7 |

−2.4 to 3.8 |

0.7 |

5.0 (14.4) |

11.1 (21.3) |

3.9 |

0.5 to 7.4 |

0.026 |

| Use of any prophylactic medication in 28 days | 40 (25%) | 45 (32%) | 34 (21%) | 39 (29%) | 7% | −3% to 17% | 0.15 | 22 (14%) | 37 (26%) | 13% | 4% to 22% | 0.005 |

As defined in study protocol: 35% or greater improvement in headache score from baseline.

International Headache Society definition: 50% or greater reduction in days with headache.14

Adjusted difference: positive favours acupuncture.

Table 3.

Health status as scored on the SF-36: values are means (SD)

|

Baseline |

After treatment (three months after randomisation) |

At 12 months |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End point | Acupuncture | Controls | Acupuncture | Controls | Difference* | 95% CI | P value | Acupuncture | Controls | Difference* | 95% CI | P value |

| Physical functioning |

n=161: 81.9 (21.1) |

n=139: 85.3 (18.4) |

n=156: 82.6 (20.7) |

n=134: 81.7 (21.3) |

3.0 |

−0.2 to 6.2 |

0.07 |

n=157: 82.6 (23.3) |

n=138: 82.3 (20.2) |

2.7 |

−0.7 to 6.0 |

0.12 |

| Role functioning physical |

n=161: 60.4 (40.2) |

n=139: 59.4 (38.6) |

n=154: 63.5 (41.4) |

n=134: 56.7 (40.8) |

5.0 |

−3.6 to 13.5 |

0.3 |

n=156: 70.0 (39.2) |

n=137: 60.3 (41.3) |

8.8 |

0.6 to 17.0 |

0.036 |

| Role functioning emotional |

n=160: 73.2 (36.6) |

n=140: 69.6 (39.4) |

n=155: 72.4 (39.7) |

n=130: 74.7 (36.3) |

−5.1 |

−13 to 2.9 |

0.2 |

n=154: 76.0 (37.0) |

n=136: 70.1 (39.2) |

4.9 |

−3.5 to 13.4 |

0.3 |

| Energy or fatigue |

n=161: 47.9 (19.9) |

n=140: 52.2 (20.2) |

n=154: 51.3 (21.6) |

n=134: 51.8 (20.8) |

1.9 |

−1.8 to 5.7 |

0.3 |

n=158: 55.4 (20.7) |

n=139: 54.2 (20.7) |

4.2 |

0.6 to 7.7 |

0.02 |

| Emotional wellbeing |

n=161: 66.0 (15.0) |

n=140: 67.0 (14.1) |

n=156: 66.6 (15.3) |

n=134: 67.8 (14.0) |

−0.9 |

−3.8 to 2.0 |

0.5 |

n=158: 68.3 (15.4) |

n=139: 68.9 (14.7) |

0.0 |

−2.9 to 2.9 |

1 |

| Social functioning |

n=161: 71.0 (24.9) |

n=140: 73.6 (21.6) |

n=156: 73.6 (24.8) |

n=134: 75.4 (22.6) |

−0.8 |

−5.6 to 4.1 |

0.8 |

n=158: 77.9 (25.2) |

n=138: 74.8 (23.2) |

4.2 |

−0.8 to 9.2 |

0.10 |

| Pain |

n=160: 59.8 (23.3) |

n=140: 66.3 (21.3) |

n=156: 64.3 (23.6) |

n=134: 64.6 (23.5) |

2.4 |

−2.5 to 7.3 |

0.3 |

n=158: 65.0 (24.5) |

n=139: 63.7 (22.2) |

4.4 |

−0.2 to 9.0 |

0.063 |

| General health |

n=161: 60.2 (21.1) |

n=140: 64.0 (21.8) |

n=156: 61.1 (21.1) |

n=134: 61.8 (22.1) |

2.1 |

−1.0 to 5.3 |

0.2 |

n=158: 61.9 (22.5) |

n=139: 62.5 (22.9) |

3.0 |

−0.4 to 6.5 |

0.09 |

| Health change | n=161: 52.5 (15.4) | n=140: 53.4 (17.0) | n=154: 58.0 (18.9) | n=133: 50.6 (18.3) | 7.7 | 3.5 to 12.0 | 0.0004 | n=158: 62.8 (20.1) | n=137: 55.5 (18.4) | 7.9 | 3.5 to 12.3 | 0.0004 |

Higher scores indicate better quality of life. Differences between groups are calculated by analysis of covariance.

Adjusted difference: positive favours acupuncture.

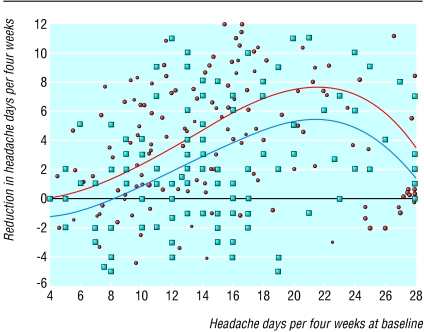

We conducted interaction analyses to determine which patients responded best to acupuncture. Although improvements in mean headache score over control were much larger for migraine patients (4.9; 95% confidence interval 2.4, 7.5, n = 284) than for patients who did not meet the criteria for migraine (1.1; 95% confidence interval - 2.4 to 4.5, n = 17), the small numbers of patients with tension-type headache preclude us from excluding an effect of acupuncture in this population. The interaction term for baseline score and group was positive and significant (P = 0.004), indicating larger effects of treatment on patients with more severe symptoms, even after controlling for regression to the mean. Predicted improvements in headache score for each quartile of baseline score in acupuncture patients are 22%, 26%, 35%, and 38%; figure 2 shows comparable data for days with headache. Neither age nor chronicity nor sex influenced the results of acupuncture treatment.

Fig 2.

Frequency of headache at baseline and after treatment. Red dots are actual values for patients in the acupuncture group; blue squares are for controls. The straight line represents no change: observations above the line improved. The curved lines are regression lines (upper red line for acupuncture, lower blue line for controls) that can be used as predictions. Some outliers have been removed

Table 4 shows data on use of resources. Patients in the acupuncture group made fewer visits to general practitioners and complementary practitioners than those not receiving acupuncture and took fewer days off sick. Confirming the excellent safety profile of acupuncture,15 the only adverse event reported was five cases of headache after treatment in four subjects.

Table 4.

Use of resources. Values are means (SD)

| Resource | Acupuncture | Controls | Difference between groups* | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of visits to: |

|||||

| General practitioner |

1.7 (2.5) |

2.3 (3.6) |

0.77 |

0.56 to 1.06 |

0.10 |

| Specialist |

0.22 (0.9) |

0.14 (0.6) |

1.13 |

0.34 to 3.73 |

0.8 |

| Complementary therapist |

2.0 (7.1) |

2.3 (6.8) |

0.56 |

0.18 to 1.72 |

0.3 |

| No of days off sick | 12.6 (18.9) | 13.8 (16.2) | 0.84 | 0.64 to 1.09 | 0.2 |

Visits to acupuncturists and physiotherapists are excluded.

Adjusted difference between groups. Results are expressed as an incident rate ratio—the proportion of events in the acupuncture group compared with controls. Values less than one indicate fewer events in the acupuncture group. For example, the value of 0.77 for visits to general practitioners means that acupuncture patients made 23% fewer visits.

Discussion

Main findings

Acupuncture in addition to standard care results in persisting, clinically relevant benefits for primary care patients with chronic headache, particularly migraine, compared with controls. We also found improvements in quality of life, decreases in use of medication and visits to general practitioners, and reductions in days off sick. Methodological strengths of our study include a large sample size, concealed randomisation, and careful follow up. We have maximised the practical value of the trial by comparing the effects of clinically relevant alternatives on a diverse group of patients recruited directly from primary care.8

Limitations

Control patients did not receive a sham acupuncture intervention. One hypothesis might be that the effects seen in the acupuncture group resulted not from the physiological action of needle insertion but from the “placebo effect.” Such an argument is not relevant to an assessment of the clinical effectiveness of acupuncture because in everyday practice, patients benefit from placebo effects. None the less, good evidence from randomised trials shows that acupuncture is superior to placebo in the treatment of migraine.7,16 Furthermore, this study was modelled on Vincent's earlier double blind, placebo controlled trial in migraine,17 which makes direct comparison possible. If placebo explained the activity of acupuncture we would expect patients in our control group, who received no treatment, to experience smaller improvements than Vincent's placebo treated controls, leading to a larger difference between groups. However, improvements in our controls (7.1% from a baseline headache score of 26.7) were similar to those in Vincent's trial (10.5% from 27.2) and differences between groups are non-significantly smaller in the current trial (4.1 v 8.1). This implies that our findings perhaps cannot be explained purely in terms of the placebo effect. That said, we are unable to rule out such an explanation given our lack of placebo control.

Patients in the trial were not blinded and may therefore have given biased assessments of their headache scores. Measures to minimise bias included minimum contact between trial participants and the study team, extended periods of anonymised diary completion and coaching patients about bias. The difference between groups is far larger (odds ratio for response 2.5) than empirical estimates of bias from failure to blind (odds ratio 1.2).18 The similarity of our results to those of the prior blinded study provides further evidence that bias does not completely explain the apparent effects of acupuncture.

Patients recorded all treatments for headache during the course of the study. Use of medication and other therapies (such as chiropractic) was lower in patients assigned to acupuncture, indicating that the superior results in this group were not due to confounding by off-study interventions.

Comparison with other studies

A strength of the current trial is that its results are congruent with much of the prior literature on acupuncture for headache. Effects found in this study that have been previously reported include: differences between acupuncture and control for migraine7,16,19 that increased between follow up after treatment and one year16; unconvincing effects for tension-type headache20-23; improvements in severity as well as frequency16,24 and increased benefit in patients with more severe headaches.16

Conclusion

A policy of using a local acupuncture service in addition to standard care results in persisting, clinically relevant benefits for primary care patients with chronic headache, particularly migraine. Expansion of NHS acupuncture services for headache should be considered.

What is already known on this topic

Acupuncture is widely used to treat chronic pain

Several small trials indicate that acupuncture may be of benefit for chronic headache disorders

The methodological quality of these studies has been questioned

What this study adds

Acupuncture led to persisting, clinically relevant reduction in headache scores

Patients receiving acupuncture used less medication, made fewer visits to general practitioners, and took fewer days away from work or other usual activities

Expansion of NHS acupuncture services for chronic headache, particularly migraine, should be considered

Additional tables A and B and a description of the sensitivity analyses are on bmj.com

Additional tables A and B and a description of the sensitivity analyses are on bmj.com

The views are those of the authors and not that of the NHS. We thank the following for their contributions: Claire Allen was consumer representative; Tim Lancaster provided advice on recruitment methods; Kate Hardy was the study nurse. Acupuncture was provided by Kyriakos Antonakos, Ann Beavis, Reg D'Souza, Joan Davies, Nadia Ellis (who is a coauthor of this paper), Sara Jeevanjee, Maureen Lovesey, Bets Mitchell, Alison Nesbitt, Steve Reece, Stephanie Ross, and Hetty Salmon-Roozen.

Contributors: AJV conceived, designed and analysed the study and is its guarantor; RWR, CEZ, CMS, and NE contributed to the original design with particular contributions to outcome assessment (RWR, CMS); patients and treatment (CEZ); acupuncture treatment (NE). RM contributed to design of resource outcome assessment; RM, RvH and PF contributed to development of data collection methods for sensitivity analysis.

Funding: The trial (ISRCTN96537534) was funded by NHS R&D National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment (NCCHTA) grant: 96/40/15.

Competing interests: NE provides acupuncture as part of her private physiotherapy practice.

Ethical approval: South West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and appropriate local ethics committees.

References

- 1.Solomon GD. Evolution of the measurement of quality of life in migraine. Neurology 1997;48(suppl): S10-15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Stewart WF, Lipton RB. The economic and social impact of migraine. Eur Neurol 1994;34(suppl 2): S12-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ, Bigal ME, Kolodner K, Liberman JN, et al. Patterns of health care utilization for migraine in England and in the United States. Neurology 2003;60: 441-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine—Current understanding and treatment. New Engl J Med 2002;346: 257-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas KJ, Nicholl JP, Fall M. Access to complementary medicine via general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51: 25-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wadlow G, Peringer E. Retrospective survey of patients of practitioners of traditional Chinese acupuncture in the UK. Complement Ther Med 1996;4: 1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melchart D, Linde K, Fischer P, Berman B, White A, Vickers A, et al. Acupuncture for idiopathic headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(1): CD001218. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA 2003;290: 1624-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vickers A, Rees R, Zollman C, Smith C, Ellis N. Acupuncture for migraine and headache in primary care: a protocol for a pragmatic, randomized trial. Complement Ther Med 1999;7: 3-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarney R, Fisher P, van Haselen R. Accruing large numbers of patients in primary care trials by retrospective recruitment methods. Complement Ther Med 2002;10: 63-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia 1988;8: 1-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masters-Steedman S, Middaugh SJ, Kee WG, Carson DS, Harden RN, Miller MC. Chronic-pain medications: equivalence levels and method of quantifying usage. Clin J Pain 1992;8: 204-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kee WG, Steedman S, Middaugh SJ. Medication quantification scale (MQS): update of detriment weights and medication additions. Am J Pain Management 1998;8: 83-8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tfelt-Hansen P, Block G, Dahlof C, Diener HC, Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: second edition. Cephalalgia 2000;20: 765-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, Ernst E. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ 2001;323: 485-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melchart D, Thormaehlen J, Hager S, Liao J, Linde K, Weidenhammer W. Acupuncture versus placebo versus sumatriptan for early treatment of migraine attacks: a randomized controlled trial. J Intern Med 2003;253: 181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincent CA. A controlled trial of the treatment of migraine by acupuncture. Clin J Pain 1989;5: 305-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273: 408-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico PE, Airola G, Tolardo G, Mana O, et al. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache 2002;42: 855-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White AR, Eddleston C, Hardie R, Resch KL, Ernst E. A pilot study of acupuncture for tension headache, using a novel placebo. Acupuncture Med 1996;14: 11-5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karst M, Rollnik JD, Fink M, Reinhard M, Piepenbrock S. Pressure pain threshold and needle acupuncture in chronic tension-type headache—a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Pain 2000;88: 199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karakurum B, Karaalin O, Coskun O, Dora B, Ucler S, Inan L. The “dry-needle technique”: intramuscular stimulation in tension-type headache. Cephalalgia 2001;21: 813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karst M, Reinhard M, Thum P, Wiese B, Rollnik J, Fink M. Needle acupuncture in tension-type headache: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 2001;21: 637-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenhard L, Waite P. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine headaches: pilot study. N Z Med J 1983;96: 663-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]