Abstract

Hippocampus is essentially involved in learning and memory processes, and is known to be a target for androgen actions. The high density of the androgen receptors in hippocampus shows that there must be some relationship between androgens and memory. Androgen effects on spatial memory are complex and contradictory. Some evidence suggests a positive correlation between androgens and spatial memory. While some other reports indicated an impairment effect. The present study was conducted to assess the effect of 3α diol on spatial discrimination of rats. Adult male rats were bilaterally cannulated into CA1 region of hippocampus and then received 3α diol (0.2, 1, 3 and 6 μg/ 0.5 μL/side), indomethacin (1.5, 3 and 6 μg/ 0.5 μL/side), indomethacin (3 μg/ 0.5 μL/side) + 3α diol (1μg/ 0.5 μL/side), 25-35 min before training in Morris Water Maze task. Our results showed that injection of 3α diol (1, 3 and 6 μg/ 0.5 μL/ side) and indomethacin (3 and 6 μg/ 0.5 μL/side) significantly increased the escape latency and traveled distance to find hidden platform. It is concluded that intra CA1 administration of 3α diol and indomethacin could impair spatial learning and memory in acquisition stage. However, intra hippocampal injection of indomethacin plus 3α diol could not change spatial learning and memory impairment effect of indomethacin or 3α diol in Morris Water Maze task.

Key Words: Androgens, Spatial memory, 3α diol, indomethacin, Morris water maze, GABAA receptor

Introduction

Steroid hormones are synthesized in the gonads and reach brain via the blood circulation (1, 2). In addition, the local endogenous synthesis of estrogens and androgens from cholesterol occurs in glial cells, astrocytes and neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system by the mediation of cytochrome P450 and non P450 enzymes (1-4). Steroids not only affect the sexual behavior responses, but also the ability of the brain to process, store and retrieve sensory information. Neuromodulatory function of steroid hormones have been investigated in the hippocampus, because the hippocampus is attractive as a center of learning and memory (2). Androgens can enhance neural excitability in the hippocampus of male rats and increase dendritic spine density in the CA1 and CA3 regions of the dorsal hippocampus (5).

Changes in gonadal steroids levels over the time of life, in addition to causing the variations in cognitive function, contribute to neurodegenerative disorder such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (6-8).

The male rat hippocampus is rich in androgen receptors expressing cells (1, 9, 10), so that the much of the work on steroid-induced learning, has focused on the effects of androgens in the hippocampal spatial memory. The literature of androgen effects on spatial memory is complex and contradictory (1, 5, 9-11). Some evidence suggests that androgens can impair memory in animals (12). It has been shown that the injection of testosterone in the CA1 region of hippocampus impaired spatial memory in adult male rats (1, 9, 10, 13-17). Several reports also indicated that chronic treatment with androgens impaired spatial learning and retention of spatial information in young and middle-aged animals (13, 18). In contrast, some studies show a positive correlation between testosterone (T) and its metabolites and spatial ability (19-23). For instance men with lower levels of T due to hypogonadism or aging demonstrate poorer cognitive performance, and these deficits can be reduced by androgen-replacement therapy (21, 24). Also studies in animal models have shown that gonadectomized (GDX) male rodent show poorer performance in spatial learning (25).

One of the complexities in understanding the effects of androgens is that these steroids have very broad spectrum of activity. At least in part, this is because androgens represent substrate for the synthesis of several biologically active metabolites (6, 26).

Our previous studies showed that testosterone impaired learning and memory (1, 5, 9, 10, 11). An important question is how it may have its effects on spatial memory. Testosterone is readily metabolized in the brain by the 5α-reductase enzyme to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which is subsequently converted by the 3α –hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzyme (3α-HSD) to nonaromatizable metabolite 5α –androstan-3α, 17β- diol (3α-diol) (20, 27, 28). Systematic administration of 3α-diol to gonadectomized (GDX) rats enhances cognitive performance in the inhibitory avoidance, place learning and object recognition tasks (28); however, there is no information about the effect of intrahippocampal injection of 3α-diol on spatial learning and memory.

Indomethacin is a poorly water-soluble, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (29) anda prostaglandin blocker which powerfully inhibits 3α-HSD reduction (30). Indomethacin can act as a 3α-HSD inhibitor, then, by blocking testosterone and DHT‘s metabolism to 3α-diol, it can affect memory process. Some of studies have shown that indomethacin as 3α-HSD blocker may affect on testosterone and 3α-diol metabolism in spatial learning and memory procedure (20, 28). In addition, it is well known as a nonselective COX inhibitor. COX (cyclooxygenase) enzymes catalyze the first two committed steps in the biosynthesis of prostanoids (30-33). Indomethacin as a nonselective COX inhibitor, can affect on learning and memory. Several lines of evidence indicate a potential role for COX in the physiological mechanisms underlying memory function. For example, nonspecific COX inhibitors such as indomethacin impair passive avoidance memory in chicks and prevent the learning-induced increase in prostaglandin (PG) release, which occurs 2 h after training (33).

Because of the contradictory effects of testosterone and its metabolites on spatial learning and memory and also as there is no information about hippocampal effect of 3α-diol, in this study we investigated the effect of intrahippocampal administration of 3α-diol on learning and memory in presence or absence of indomethacin (3α-HSD blocker) in Morris Water Maze task.

Experimental

Male albino Wistar rats (200-250 g) obtained from the Pasteur Institute of Iran were used in experiments. Rats were housed five per cage in large cages before surgery and individually in small cages after surgery, and were maintained at room temperature of 23 ± 2 ºC under standard 12:12 h light-dark cycle with lights on at 07:00 am. Food and water were available ad libitum. Experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the recommendations internationally accepted principles for the use of experimental animals.

Surgery

Rats were anesthetized using a ketamineandxylazine (100 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg, IP) and placed in a stereotaxic instrument (Stoelting, USA). Bilateral guide cannulas were implanted in the right and left CA1 and were attached to the skull surface using dental cement jeweler’s screws. Stereotaxic coordinates based on Paxinos and Watson’s Atlas of the rat brain (34) was: anterior-posterior (AP), -3.8 mm from bregma; medial-lateral (ML), ±2.2 mm from midline; and dorsal-ventral (DV), -2.7 mm from the skull surface.

Microinjection procedure

Intracerebral injections were administered through guide cannula (23-gauge) using injection needles (30-gauge) connected by polyethylene tubing to 0.5 μL Hamilton microsyringes. The injection needle was inserted 0.5 mm beyond the tip of the cannula. Then 0.5 μL of vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) or different doses of 3α- diol (Sigma, U.S.A) and indomethacin (Daroopakhsh Co. Iran) were injected into each side of CA1 region during 2 min and the needles were left in place for an additional 60 s to allow for diffusion of solution away from the needle tip. DMSO and 3α- diol were injected 30-35 min and indomethacin 20-25 min before testing each day. The other procedure of injection was administered for rats that received two drugs or two doses of vehicle together. In this procedure 0.5 μL of DMSO plus 0.5 μL DMSO were injected in intact and sham group with 30 min interval, also 3 μg/ 0.5 μL of indomethacin plus 1 μg /0.5 μL of 3α- diol were injected with 25 min interval. Then the test began after a delay of 30 min each day.

Behavioral assessment

Apparatus

The Morris Water Maze (MWM) is one of the most frequently used laboratory tools in behavioral neuroscience (35) that relies on distal cues to navigate away from start locations around the perimeter of an open swimming area to locate a submerged escape platform (36, 37). The water maze is a black circular tank 140 cm in diameter and 60 cm in height. The tank was filled with water (21±1ºC) to a depth of 25 cm. The maze was located in a room containing many extra maze cues (e.g. bookshelves, refrigerator, and posters). The maze was divided geographically into four quadrants (Northeast (NE), Northwest (NW), Southeast (SE), Southwest (SW)) and starting positions (North (N), South (S), east (E),West (W)) that were equally spaced around the perimeter of the tank. A hidden circular platform (diameter 10 cm) was located in the center of the SW quadrant, submerged 1 cm below the surface of the water. A video camera above the water maze was connected to a video monitor and computer software (Ethovision XT, version 7), and was used to track the animals‘ path and to calculate the escape latency, traveled distance and swimming speed.

Procedure

Each animal received four trials of one block per day in 4 consecutive days (11, 16). Each rat was placed in the water facing the wall of the tank at one of the four designated starting points and was allowed to swim and find the hidden platform located in SW quadrant of the maze on every trial. Starting points varied in a quasi-random fashion so that in each trial the animal started from each location only once and never started from the same place again. During each trial, each rat was given 90 s to find the hidden platform. If rat found the platform it was allowed to remain on it for 20 sec. If rat failed to find the platform within 90 sec, it was placed on platform for 20 sec. During the first 4 days the platform position remained constant. On day 5, the platform was elevated above the water surface and placed in SE quadrant. This assessed Visio-motor coordination toward a visible platform. All tests began at 8:00 am.

Histology

Following behavioral testing, animals were sacrificed by decapitation and brains were removed. For histological examination of cannulae and needle placement in CA1 region, 100 μm thick sections was taken, mounted on slides, stained with cresyl violet and the cannulae track was examined for each rat. Only those animals whose cannulae were exactly placed in the CA1 region were used for data analysis.

Experiment 1

The first experimental group consisting of intact and sham-operated rats received bilateral microinjection of 0.5 μL vehicle (DMSO or 0.5 μL DMSO+0.5 μL DMSO) into CA1 region of hippocampus. The aim of this experiment was to compare the effects of intrahippocampal vehicle injection with intact group of rats on MWM performance. A total of 27 rats were divided into three groups mentioned above.

Experiment 2

The aim of this experiment was to determine the effect of intrahippocampal 3α-diol injection (one of the metabolites of testosterone), on MWM performance. A total of 40 rats were divided into four groups and received different doses of 3α- diol (0.2, 1, 3 and 6 μg/0.5 μL/side) 30-35 min before MWM test.

Experiment 3

The aim of this experiment was to determine the effect of intrahippocampal indomethacin injection (as a 3α-HSD inhibitor) on MWM performance. A total of 27 rats were divided into three groups and received different doses of indomethacin (1.5, 3 and 6 μg/0.5 μL/side) 20-25 min before MWM test.

Experiment 4

The aim of this experiment was to determine the effect of intrahippocampal injection of indomethacin plus 3α- diol, on MWM performance. A total of 8 rats were received 3 μg/0.5 μL/side indomethacin + 1 μg/0.5 μL/side 3α- diol respectively, 30 min before test.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was done by Kolmogorov-semimov test at first, to examine the normal distribution. Data obtained over training days from hidden platform tests and in visible platform were analyzed by t-test for comparison between two groups and one- way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey,s test for multiple comparisons. All results have been shown as mean ± SEM. In all statistical comparisons, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Experiment 1: the effects of vehicles

Hidden platform trials (days 1-4)

The results obtained from intact, vehicle (DMSO and DMSO+DMSO) indicate no significant difference in escape latency (F2, 80= 0.211, p = 0.810), traveled distance (F2, 80 =1.197, p = 0.307) and swim speed between groups (F2, 80=1.838, p = 0.166). These results indicated that injection of DMSO or injection DMSO+DMSO together had no effect on spatial learning and swimming ability.

Visible platform trials (day 5)

There was no significant difference in performance among intact, DMSO and DMSO+DMSO groups on the visible platform for latency (F2, 19=0.36, p = 0.965) or for traveled distance (F2, 19=0.347, p = 0.712).

Experiment 2: the effect of 3α-diol

Hidden platform trials (days 1-4)

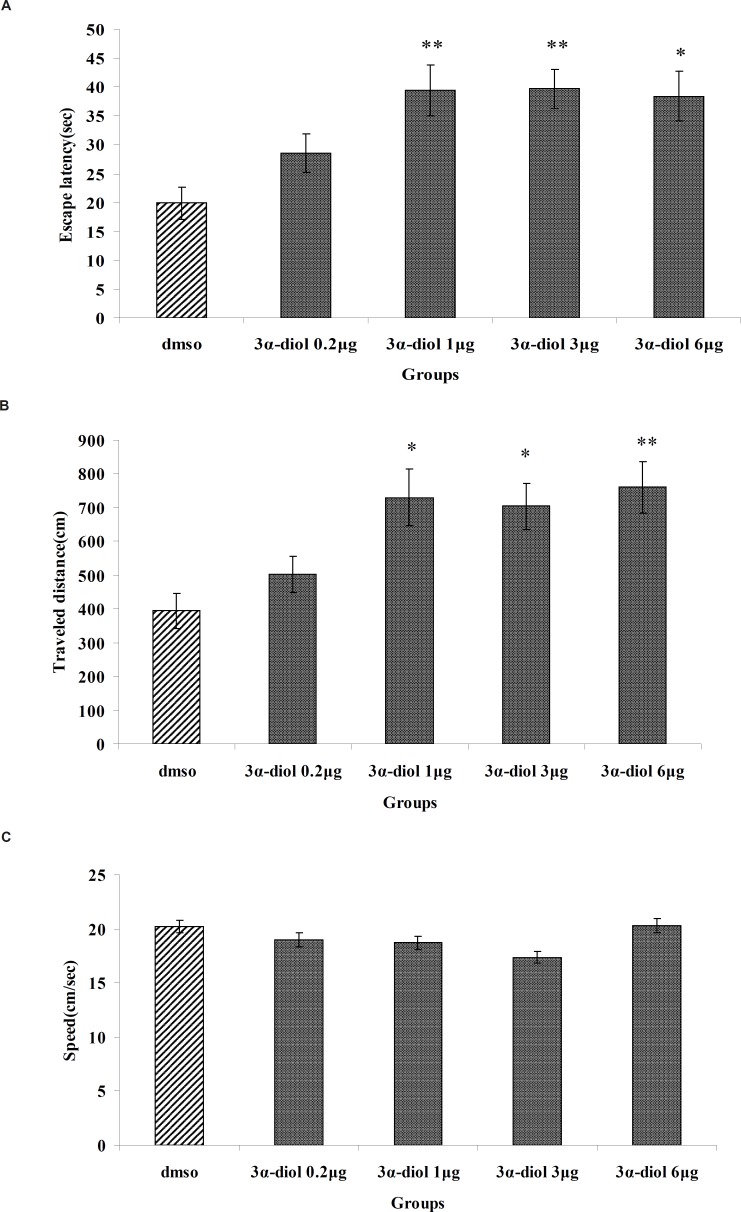

Figure 1 show results obtained from the injection of 3α-diol or DMSO (control). A significant difference was generally found in escape latency (F5, 166= 5.713, p < 0.001) and traveled distance (F5, 166= 5.281, p < 0.001) between groups (fig. 1A and B). But no significant differences found in swimming speed (F5, 166= 1.825, p > 0.05) (Figure 1C). Post hoc multiple comparisons showed that 3α- diol at dose of 1, 3 and 6 μg significantly impaired acquisition of spatial learning compared to the control group.

Figure 1.

The effect of intra-CA1 administration of 3α-diol and DMSO on acquisition of spatial memory in MWM task. The columns represent the mean ± SEM. average escape latency (A) traveled distance (B) and swimming speed (C) across all training days (* p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 indicate significant difference vs. DMSO group).

Visible platform trials (day5)

There was no significant difference of performance among the groups on visible platform day for escape latency (F5, 41=0.741, p = 0.597) or for traveled distance (F5, 41=1.173, p = 0.339).

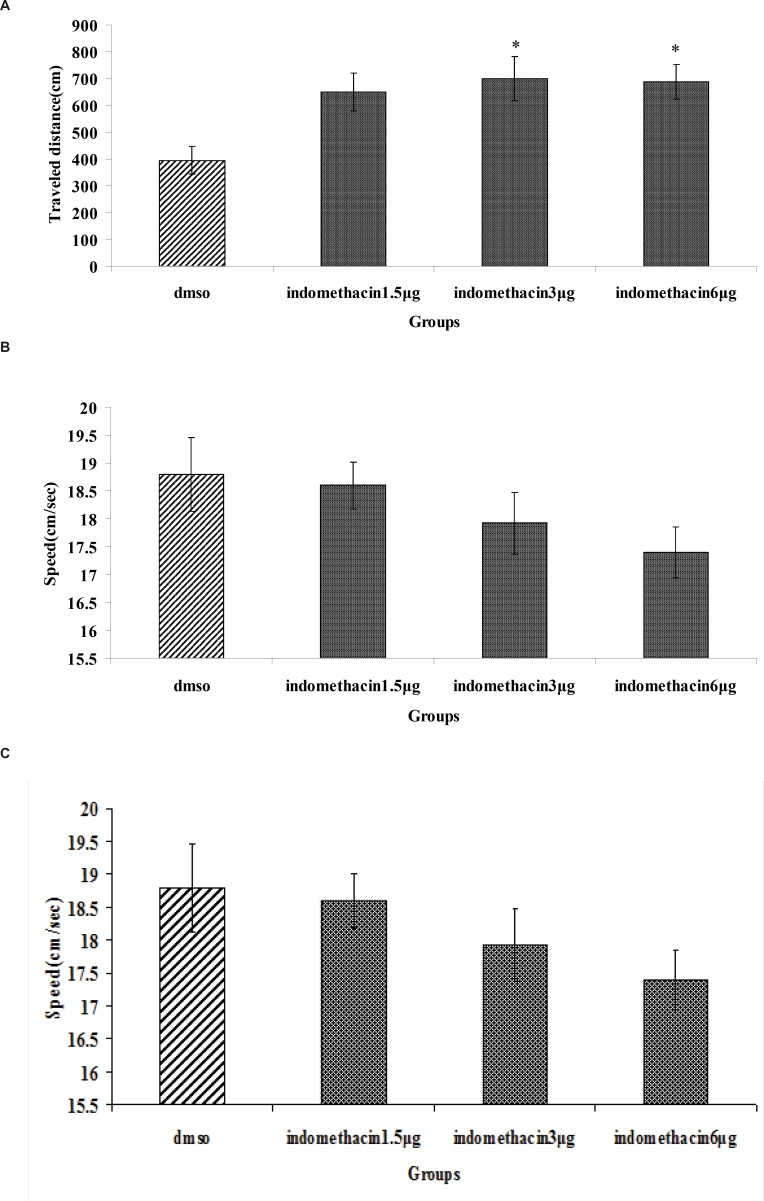

Experiment 3: the effect of indomethacin

Hidden platform trials (days 1-4)

The effect of indomethacin or DMSO (control) is shown in Figure 2. A significant difference was generally found in escape latency (F3, 112=4.974, p = 0.003) and traveled distances (F3, 112=3.761, p = 0.013) between groups (Figure 2A and B). But no significant differences were found in swimming speed (F3, 112=1.530, p=0.211) (Figure 2C). Post hoc multiple comparisons showed that the rats treated with 3 and 6 μg indomethacin had significantly impaired acquisition of spatial learning compared to the control group.

Figure 2.

The effect of intra-CA1 administration of indomethacin and DMSO on acquisition of spatial memory in MWM task. The columns represent the mean ± S.E.M. average escape latency (A), traveled distance (B) and swimming speed (C) across all training days (* p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 indicate significant difference vs. DMSO group).

Visible platform trials (day5)

There was no significant difference of performance among the groups on visible platform day for escape latency (F3, 28=0.790, p = 0.510) or for traveled distance (F3, 28=2.625, p = 0.075).

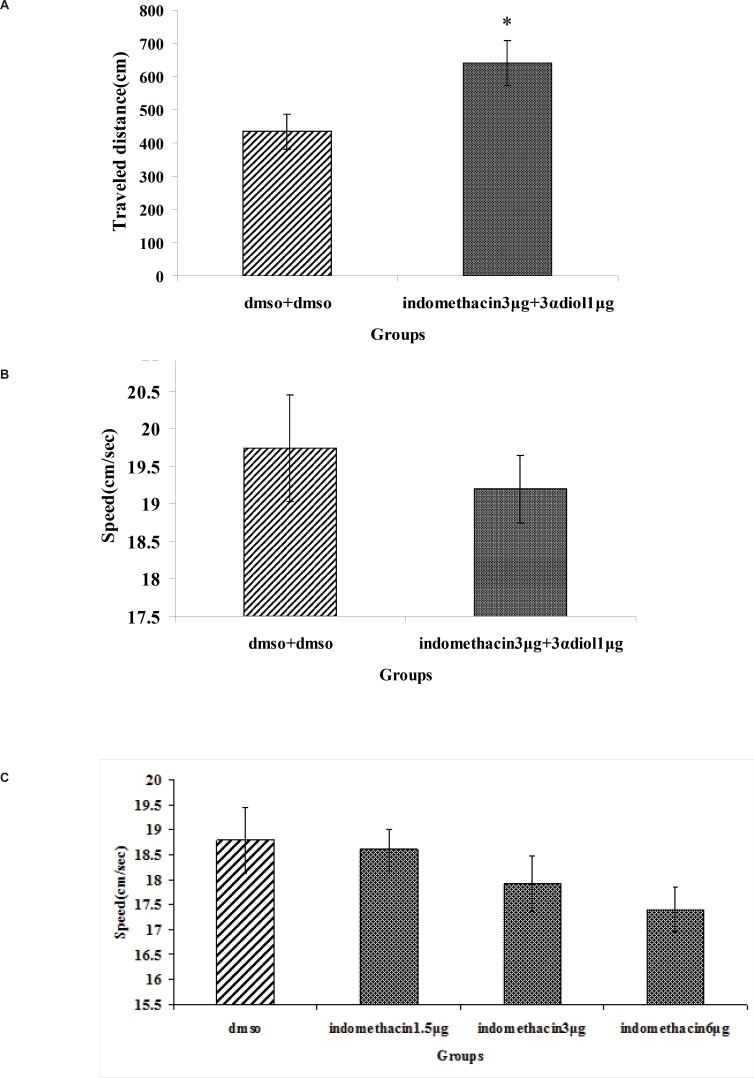

Experiment 4: The effect of indomethacin + 3α-diol

Hidden platform trials (days 1-4)

A significant difference was generally found in escape latency (T62=4.65, p = 0.029) and traveled distance (T62=3.265, p = 0.02) (Figure 3A and B). But no significant differences were found in swimming speed (T62=10.885, p = 0.521) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

The effect of intra-CA1 administration of indomethacin + 3α- diol and DMSO + DMSO on acquisition of spatial memory in MWM task. The columns represent the mean ± SEM. average escape latency (A), traveled distance (B) and swimming speed (C) across all training days (* p < 0.05 indicate significant difference vs. DMSO + DMSO group).

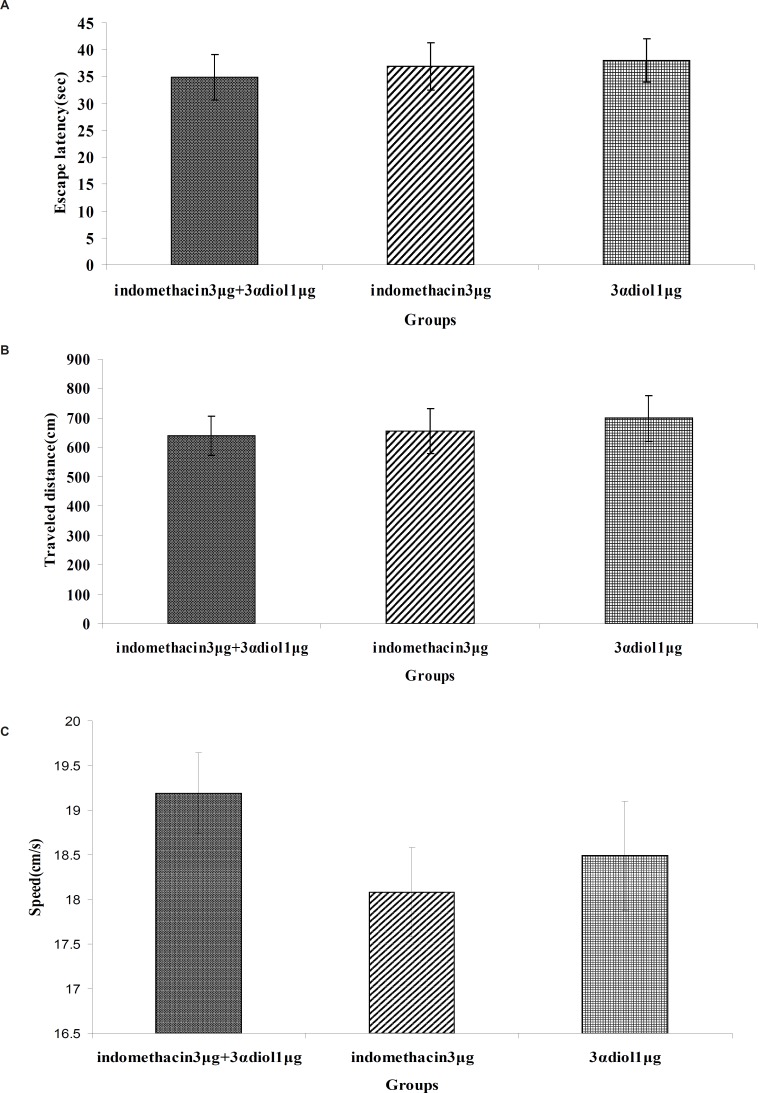

Fig. 4(A, B and C) revealed that there were no significant differences in escape latency(F2,97= 0.139, p = 0.870), traveled distance (F2,97= 0.170, p = 0.844) and swimming speed (F2,97=1.054, p = 0.353) between indomethacin 3 μg + 3α- diol 1 μg , indomethacin 3 μg and 3α- diol 1 μg group. These data indicated that presence of indomethacin can not inhibit impairing effect of 3α- diol on spatial memory.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the effect of intra-CA1 administration of indomethacin + 3α-diol, indomethacin and 3α-diol on acquisition of spatial memory in MWM task. The columns represent the mean ± SEM. average escape latency (A), traveled distance (B) and swimming speed (C) across all training days. There was no significant differences between the three groups

Visible platform trials (day5)

There was no significant difference of performance among the groups on visible platform day for escape latency (F14=2.912, p = 0.697) or for traveled distance (F14=3.204, p = 0.421).

Discussion

Our experiments showed that there was not significant difference in spatial learning and memory among the intact rats and sham operated groups (DMSO and DMSO+DMSO). DMSO was used as a vehicle in other investigation with similar conditions (10, 11). In this experiment we saw that the double injection of vehicle (DMSO+DMSO) had no significant effect on learning and memory. This finding is consistent with some other reports (1, 5, 9, 10, 11, 16).

The results of experiment 2 indicated that intrahippocampal injection of 3α- diol in doses 1, 3 and 6 μg/0.5 μL impaired spatial learning in adult male rats in MWM task.

Since there were no significant differences between the control and experimental groups on the 5th day of training in visible platform, it can be inferred that the observed changes could not be attributed to alterations of non-mnemonic factors such as motivation, motor, or sensory processes induced by the treatments.

This study, taken with other previous ones shows conflicting effects of androgens on cognition and suggests that cognitive-hormone interactions are quite complex. In several studies, androgens impaired spatial learning and memory (1, 5, 9, 10, 14-16) however, some other studies reported that androgens such as testosterone enhanced spatial memory (19-23).

Androgens could exert these effects on memory through genomic and non-genomic pathways. The genomic pathway typically takes at least more than half an hour and involves long-term effects of androgens affecting gene expression via the intracellular androgen receptors. In addition to the classical genomic effects of steroids, many neurosteroids induce non-genomic effects by means of putative cell surface receptors that are manifested within in seconds to few minutes which can involve the modulation of neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels, ranging from activation of G-protein coupled membrane receptors or sex hormone- binding globulin receptors, stimulation of different protein kinases to direct modulation of voltage and gated ion- channels and transporters (5, 9, 11, 38-40).

Our previous study revealed that testosterone via both genomic and non-genomic pathways impairs long term memory (9).

It has been demonstrated that neurons and glia express enzymes able to convert testosterone to estradiol and several 5α-reduced androgens such as dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Further metabolism of DHT results in the formation of 5α-androstane-3,17β –diol (3α-diol) (41), that is capable of eliciting estrogen receptor-dependent responses (42-44). There are several possible explanations for the impairing effect of 3α-diol on spatial memory. The first possibility is that the oxidative 3 hydroxy steroid dehydrogenases (HSDs) can convert 3α-diol back to DHT, leading to increased androgenic stimulation. Since, DHT has stronger androgenic effect than to 3α-diol (44), the obtained results may be related to the conversion of 3α-diol to DHT then to testosterone. In this way, androgen responsiveness is considered to depend on steroid transforming enzymes in brain (44).

The second possibility is based on this fact that in addition to the effect on estrogen receptor (ER), 3α-diol also affects on learning and memory through non-genomic pathway. One of the best-documented examples of non-genomic actions of steroids is the ability of these hormones to activate GABAA receptors. Neurosteroids have been reported to modulate GABAergic function by increasing GABAA receptor opening frequency and duration (6). Activation of the GABAA receptor complex by such neurosteroids results in opening of its central Cl- conducting pore, which leads to a hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane and inhibition of neuronal firing (40). The major groups of neuroactive steroids and their metabolites are progesterone, dehydrocorticosterone and some of their metabolites. 3α-diol acts like the analogous metabolites of progesterone and corticosterone, such as allopregnanolon, that enhances GABA-benzodiazepine regulated chloride channel function (42, 44, 45). In general, they mediate their actions not through classic steroid receptors, but through other mechanisms such as ligand-gated ion-channels including GABAA, glutamate or opioid receptors (40). On the other hand the biphasic effects of progesterone are consistent with a critical role for GABA-mediated responses. Progesterone, like DHT, is rapidly converted in the brain to 5α–reduced metabolites, some of which potentiate GABA action on the GABA-benzodiazepine-chloride channel complex (6). Therefore the effects of androgens such as 3α-diol could be mediated in much the same way as the rapid responses of progesterone, via enhancement of GABAergic neurotransmission.

Beside, some studies have shown that all hippocampal subregions are rich in GABAA receptors and that some neurosteroids such as allopregnanolone can inhibit neural activity in the CA1 and dental gyrus areas of the hippocampus (3, 46, 47). Treatment with GABAA receptor active substances such as, benzodiazepine, can inhibit learning and memory in humans and animals (3, 38). Acute treatment with neurosteroids that have GABA-modulatory effects impairs learning and memory. In contrast, steroids that act as GABAA receptor antagonists enhance learning and memory (48-50).

The third possibility is based on this fact that there is an interaction between steroids and the serotonin system in the hippocampus. Some evidence showed that steroids such as estrogen and also progesterone metabolites such as alloprognanolone can affect spatial learning and memory via the serotonin system (19). Additionally, a direct interaction between the GABA and the serotonin systems in the hippocampus is proven, where serotoninergic neurons often end at inhibitory GABAergic interneurons (3, 51). Many studies have shown that excitation of serotoninergic neurotransmission impairs learning and memory, whereas, reduction of serotonin activity can improve these processes (51-54). Serotonin and GABA systems may therefore interact in the hippocampus; a region important for cognitive functions (3, 56) and 3α-diol, probably via this way induce impairment in learning and memory performance.

Steroid hormones also modulate the memory processes perhaps by their relationship with other neurotransmitter system such as acetylcholine, dopamine, noradrenaline and glutamate, and by their relationship with the cerebral regions that participate in these phenomena (5, 10). Based on the evidences, testosterone and its metabolites, 3α-diol, can reduce acetylecholine release in the hippocampus, via positively modulationg hippocampal GABAergic interneurons that is shown to induce memory impairment (5, 57). Many studies have also shown that NMDA receptors are critical for synaptic plasticity and long term memory (LTM) (53, 58, 59). Testosterone by acting as non-selective sigma (σ) antagonist may produce a tonic damping of the function of sigma receptors and consequently a decrease in NMDA receptor function (5, 60). Therefore, these facts provide a reliable evidence for the explanation the effects of 3α-diol (as a one metabolite of testosterone) on spatial learning and memory.

The results of experiment 3 indicated that intrahippocampal injection of indomethacin at doses 3 and 6 μg/0.5 μL impaired spatial learning in adult male rats.

The results of experiment 4 showed that intrahippocampal injection of indomethacin 3 μg/0.5 μL +3α A-diol 1 μg/0.5 μL, impaired spatial learning and memory in adult male rats, similar to indomethacin and 3α A-diol.

Our reason for using indomethacin come from the Frye et al. (2010) which mentioned that indomethacin can act as 3α-HSD inhibitor. Further blocking testosterone’s or DHT‘s metabolism to 3α-diol with indomethacin decreases cognitive performance and increases anxiety behavior of gonadally-intact and/or DHT-replaced rats (20, 28). In experiments 2 and 3 we assayed the effect of 3α-diol and indomethacin alone on learning and memory. Our finding shows that both 3α-diol and indomethacin impaired acquisition learning and memory performance. In experiment 4, we used indomethacin as 3α-HSD inhibitor to prevent the effect of endogenous 3α-diol on learning and memory and then studied the effect of exogenous 3α-diol on the acquisition stage of learning and memory. Our results show that exogenous 3α-diol has impairment effect on acquisition memory and indomethacin could not prevent the impairing effect of 3α-diol while indomethacin had impairment effects of its own. Beside, there is no significant difference between intra-CA1 administration of indomethacin + 3α-diol, indomethacin and 3α-diol on acquisition stage using one way ANOVA. It is possible that 3α-diol’s effects to impair cognitive performance cannot be influenced by indomethacin. On the other hand, indomethacin as a nonselective COX inhibitor (31-33), and can affect learning and memory. Thus, COX (cyclooxygenase) enzymes catalyze the first two committed steps in the biosynthesis of prostanoids. Several lines of evidence indicate a potential role for COX in the physiological mechanisms underlying memory function and indomethacin as COX inhibitors impair these mechanisms. For example, indomethacin as a COX inhibitors impairs passive avoidance memory in chicks and prevents the learning- induced increase in prostaglandin (PG) release, which occurs 2 h after training (33).

In summary, it is concluded that intra CA1 administration of 3α diol and indomethacin could impair spatial learning and memory. Also intra hippocampal injection of indomethacin plus 3α-diol could not change spatial learning and memory impairment effect of indomethacin or 3α-diol in MWM task.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Department of Physiology and Pharmacology of Pasteur Institute for supporting this research by a grant.

References

- 1.EmamianSh , Naghdi N, Sepehri H, Jahanshahi M, Sadeghi Y, Choopani S. Learning impairment caused by intra-CA1 microinjection of testosterone increases the number of astrocytes. Behav. Brain. Res. 2010;208:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hojo Y, Murakami G, Mukai H, Higo Sh, Hatanaka Y, Ogiue-Ikeda M, Ishii H, Kimoto T, Kawato S. Estrogen synthesis in the brain-Role in synaptic plasticity and memory. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2008;290:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birzniece V, Bäckström T, Johansson IM, Lindblad C, Lundgren P, Löfgren M, Olsson T, Ragagnin G, Taube M, Turkmen S, Wang MD, Wihlbäck AC, Zhu D. Neuroactive steroid effects on cognitive functions with a focus on the serotonin and GABA systems. Brain. Res. Rev. 2006;51:212–239. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellon SH, Griffin LD. Neurosteroids: biochemistry and clinical significance. Trends. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;13:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harooni HE, Naghdi N, Sepehri H, HaeriRohani A. Intra hippocampal injection of testosterone impaired acquisition, consolidation and retrieval of inhibitory avoidance learning and memory in adult male rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 2008;188:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maclusky NJ, Hajszan T, Prange-kiel J, Leranth C. Androgen modulation of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience. 2006;138:957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, Kawas C, Blackman MR, Harman SM, Resnick SM. Free testosterone and risk for Alzheimer disease in older men. Neurology. 2004;62:188–193. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang MX, Jacobs D, Stern Y, Marder K, schofield P, Gurland B, Andrews H, Mayeux R. Effect of oesterogen during menopause on risk and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1996;348:429–432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naghdi N, Asadollahi A. Genomic and nongenomic effects of intahippocampal microinjection of testosterone on long-term memory in male adult rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 2004;153:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naghdi N, Nafisy N, Majlessi N. The effects of intrahippocampal testosterone and flutamide on spatial localization in the Morris water maze. Brain. Res. 2001;897:44–51. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naghdi N, Majlessi N, Bozorgmehr T. The effect of intrahippocampal injection of testosterone enanthate (an androgen receptor agonist) and anisomysin (protein synthesis inhibitor) on spatial learning and memory in adult, male rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 2005;156:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brosens JJ, Tullet J, Varshochi R, Lam EWF. Steroid receptor action. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2004;18:265–283. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouchie C, Kimura D. The relationship between testosterone levels and cognitive ability patterns. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1991;16:323–334. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(91)90018-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goudsmith E, Van De Poll NE, Swaab DF. Testosterone fails to reserve spatial memory decline in aged rats and impairs retention in young and middle-aged animals. Behav. Neural. Biol. 1990;53:6–20. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(90)90729-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hampson E. Spatial cognition in humans: possible modulation by androgens and esterogens. J. Psychiatry. Neurosci. 1995;20:397–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moradpour F, Naghdi N, Fathollahi Y. Anastrozole improved testosterone-induced impairment acquisition of spatial learning and memory in the hippocampal CA1 region in adult male rats. Behav. Brain. Res. 2006;175:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talebi A, Naghdi N, Sepehri H, RezayofA The Role of Estrogen Receptors on Spatial Learning and Memory in CA1 Region of Adult Male Rat Hippocampus. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2010;9:183–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogiue-Ikeda M, Tanabe N, Mukai H, Hojo Y, Murakami G, Tsurugizawa T, Takata N, Kimoto T, Kawato S. Rapid modulation of synaptic plasticity by estrogens as well as endocrine disrupters in hippocampal neuron. Brain. Res. Rev. 2008;57:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander GM, Packard MG, Hines M. Testosterone has rewarding affective properties in male rats: implications for the biological basis of sexual motivation. Behav. Neurosci. 1994;108:424–428. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frye CA, Edinger KL, Seliga AM, Wawrzycki JM. 5α–reduced androgens may have actions in the hippocampus to enhance cognitive performance of male rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janowsky JS, Oviatt SK, Orwoll ES. Testosterone influences spatial cognition in older men. Behav. Neurosci. 1994;108:325–332. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborne DM, Edinger K, Frye CA. Chronic administration of androgens with actions at estrogen receptor beta have anti-anexiety and cognitive-enhancing effects in male rats. AGE. 2009;31:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9114-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandsrom NJ, Kim JH, Wasserman MA. Testosterone modulates performance on a spatial working memory task in male rats. Horm. Behav. 2006;50:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund BC, Bever-Stille KA, Perry PJ. Testosterone and andropause: the feasibility of testosterone replacement therapy in older men. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;8:951–956. doi: 10.1592/phco.19.11.951.31574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vazquez-Pereyara F, Rivas-Arancibia S, Loaeza-Del Castillo A, Schneider Rivas S. Modulation of short term and long term memory by steroid sexual hormones. Life. Sci. 1995;56:255–260. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00067-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labrie F, Luu-The V, Labrie C, Belanger A, Simard J, Lin SX, Pelletier G. Endocrine and intracrine sources of androgens in women: inhibition of breast cancer and other roles of androgens and their precursor dehydroepiandrosterone. Endocr. Rev. 2003;24:152–182. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinlein CA, Chang C. The role of androgen receptors and androgen-binding proteins in nongenomic androgen actions. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;16:2181–2187. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frye CA, Edinger KL, Lephart ED, Walf AA. 3α-androstanediol, but not testosterone, attenuates age-related decrements in cognitive, anxiety, and depressive behavior of male rats. Aging. Neurosci. 2010;2:1–21. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nokhodchi A, Javadzadeh Y, Siahi-shadbad MR, Barzegar-jalali M. The effect of type and concentration of vehicles on dissolution rate of a poorly soluble drug (indomethacin) from liquisolid compacts. J. pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2005;8:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders BK. Sex, drugs and sports: prostaglandins, epitestosterone and sexual development. Med. Hypotheses. 2007;69:829–835. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institoris A, Farkas E, Berczi S, Sule Z, Bari F. Effects of cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition on memory impairment and hippocampal damage in the early period of cerebral hypoperfusion in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;574:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lima M, Reksidler A, Vital M. Cyclooxygenases inhibitors indomethacin and picroxicam produced dual effects on dopamine-related behaviors in rats. RevistaSaúde e Ambiente-Health and Environment J. 2008;9:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teather LA, Packard MG, Bazan NG. Post-Training Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibition impairs memory Consolidation. Learn. Mem. 2002;9:41–47. doi: 10.1101/lm.43602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paxinos G. Watson C. 2nd ed. New York: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hooge R D, De Deyn PP. Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain. Res. Rev. 2001;36:60–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mora Paul C, Magda G, Abel S. Spatial memory: Theoretical basis and comparative review on experimental methods in rodents. Behav. Brain. Res. 2009;203:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in thetreatment of insomnia. CMAJ. 2000;162:225–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Azzawi FA. Mechanism of androgen receptor action. Maturitas. 2008;63:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michels G, Hoppe UC. Rapid actions of androgens. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:182–198. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy DS. Testosterone modulation of seizure susceptibility is mediated by neurosteroids 3α- androstanediol and 17β-estradiol. Neuroscience. 2004;129:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genazzani AR, Pluchino N, Freschi L, Ninni F, Luisi M. Androgens and the brain. Maturitas. 2007;57:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pak TR, Chung WC, Lund TD, Hinds LR, Clay CM, Handa RJ. The androgen metabolite, 5 apha-androstane-3beta, 17 beta-diol, is a potent modulator of estrogen receptor-beta 1- mediated gene transcription in neuronal cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:147–155. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettersson H, Lundqvist J, Oliw E, Norlin M. CYP7B1-mediated metabolism of 5-androstane-3,17- diol (3-Adiol): A novel pathway for potential regulation of the cellular levels of androgens and neurosteroids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1791:1206–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frye CA, Van Keuren KR, Erskine MS. Behavioral effects of 3 alpha-androstanediol.I: modulation of sexual receptivity and promotion of GABA-stimulated chloride flux. Behav. Brain. Res. 1996;79:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Landgren S, Wang MD, Backstrom T, Johansson S. Interaction between 3 alpha- hydroxyl-5 alpha-pregnan-20-one and carbachol in the control of neuronal excitability in hippocampal slices of female rats in defined phases of the oestrus. Acta. Physiol. Scand. 1998;162:77–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.0287f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain: I. Telencephalon, diencephalons, mesensephalon. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frye CA, Strugis JD. Neurosteroids affect spatial/ reference, working, and long-term memory of female rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1995;64:83–96. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathews DB, Morrow AL, Tokunaga S, McDaniel JR. Acute ethanol administration and acute allopregnanolone administration impair spatial memory in the Morris water task. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2002;26:1747–1751. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000037219.79257.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vallee M, Mayo W, Koob GF, Le Moal M. Neurosteroids in learning and memory processes. Int.Rev. Neurobiol. 2001;46:273–320. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(01)46066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacab RL, Goldman-Rakic PS. Segregation of serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT3 receptors in inhibitory circuits of the primate cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;417:337–348. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000214)417:3<337::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Zahrani S, Ho M, Martinez V, Cabrera M, Bradshaw C, Szabadi E. Effect of destruction of the 5-hydroxytryptaminergic pathways on the acquisition of temporal discrimination and memory for duration in a delayed conditional discrimination task. Psychopharmacology. 1996;123:103–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02246287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dubrovsky B. Neurosteroids, neuroactive steroids, and symptoms of affective disorders. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006;84:644–655. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McEntee , WJ , Crook TH. Serotonin, memory, and the aging brain. Psychopharmacology. 1991;103:143–149. doi: 10.1007/BF02244194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riekkinen PJR, Jäkälä P, Sirviö J, Riekkinen P. The effects of increased serotoninergic and decreased cholinergic activities on spatial navigation performance in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991;39:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90392-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sibille E, Pavlides C, Benke D, Toth M. Genetic inactivation of the serotonin (1A) receptor in mice results in down regulation of major GABA (A) receptor alpha subunits, reduction of GABA (A) receptor binding, and benzodiazepine- resistant anxiety. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:2758–2765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02758.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moor E, DeBoer P, Westerink BH. GABA receptors and benzodiazepine binding sites modulate hippocampal acetylcholine release in-vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;359:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dubrovsky BO. Steroids, neuroactive steroids and neurosteroids in psychopathology. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;29:169. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santos SD, Carvalho AL, Calderia MV, Duarte CB. Regulation of AMPA receptors and synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience. 2009;158:105–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Debonnel G, Bergeron R, Montigny CD. Potentiation by dehydroepiandrosterone of the neonatal response to N-methyl-D-aspartate in the CA3 region of the rat dorsal hippocampus: an affect mediated via sigma receptors. J. Endocrinol. 1996;150:33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]