Abstract

Voltage control over enzymatic activity in voltage-sensitive phosphatases (VSPs) is conferred by a voltage-sensing domain (VSD) located in the N terminus. These VSDs are constituted by four putative transmembrane segments (S1 to S4) resembling those found in voltage-gated ion channels. The putative fourth segment (S4) of the VSD contains positive residues that likely function as voltage-sensing elements. To study in detail how these residues sense the plasma membrane potential, we have focused on five arginines in the S4 segment of the Ciona intestinalis VSP (Ci-VSP). After implementing a histidine scan, here we show that four arginine-to-histidine mutants, namely R223H to R232H, mediate voltage-dependent proton translocation across the membrane, indicating that these residues transit through the hydrophobic core of Ci-VSP as a function of the membrane potential. These observations indicate that the charges carried by these residues are sensing charges. Furthermore, our results also show that the electrical field in VSPs is focused in a narrow hydrophobic region that separates the extracellular and intracellular space and constitutes the energy barrier for charge crossing.

INTRODUCTION

The voltage-sensitive phosphatase (VSP) isolated from the tunicate Ciona intestinalis (Ci-VSP) is a membrane-embedded, voltage-controlled phosphatase (Murata et al., 2005; Villalba-Galea, 2012b). As do other members of the VSP family, Ci-VSP exhibits enzymatic activity using phosphoinositides as substrates (Guipponi et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2001; Murata et al., 2005; Iwasaki et al., 2008; Halaszovich et al., 2009, 2012; Kohout et al., 2010; Ratzan et al., 2011; Kurokawa et al., 2012). Catalytic activity of Ci-VSP is controlled by the N terminus, which is thought to be folded into a bundle of four putative transmembrane segments forming a voltage-sensing domain (VSD; Kumánovics et al., 2002; Murata et al., 2005; Ratzan et al., 2011; Sutton et al., 2012; Villalba-Galea, 2012a). The fourth (S4) segment contains charge residues likely conferring the character of voltage sensor to this domain. The S4 segment spans from glycine 214 to glutamine 239, containing five arginines. Four of these residues, R223, R226, R229, and R232, are arranged in a canonical every-third-residue array, which is typically found in the S4 segment of voltage-gated channels (Fig. 1 A; Murata et al., 2005; Villalba-Galea, 2012b). Thus, these residues are thought to be the main sensing charge bearers in the S4 segment of Ci-VSP.

Figure 1.

Mutating R217 affects both voltage dependence and kinetics of charge movement. (A) Structural model of the VSD of Ci-VSP built using the package MODELLER and taking the structure of the chimeric potassium channel Kv1.2/Kv2.1 (2R9R; Long et al., 2007) as template. Segments S1 to S3 are displayed in gray. The S4 segment (green) contains five arginines (blue). Arginine 217 faces the extracellular space, whereas the remaining four arginines point toward the core of the VSD. (B) Sensing currents from mutants C363S, R217Q-C363S, and R217E-C363S. The HP for these recordings was −60 mV for C363S, −90 mV for R217Q-C363S (hereafter R217Q), and −120 mV for R217E-C363S (hereafter R217E). Respectively, voltage ranged from −80 to 160 mV, −120 to 40 mV, and −140 to 20 mV. (C) Net charge versus potential (Q-V) curves for the mutants C363S, R217Q, and R217E. Fitted parameters are reported in Table 1. (D) Time constant for the sensing currents of the mutants in B and C. Both R217Q and R217E displayed faster ON-sensing current than the background construct C363S at all potentials tested (see R217 modulates the voltage dependence of Ci-VSP for detail). Error bars are SD.

The fifth and most extracellular S4 arginine, R217, is located six residues away from the canonical array, suggesting that this residue may not participate in voltage sensing. However, mutating R217 to a glutamine shifts the voltage dependence of Ci-VSP toward negative potentials (Dimitrov et al., 2007; Kohout et al., 2008; Villalba-Galea et al., 2008). This observation indicates that R217 electrically interacts with the voltage-sensing machinery of the VSD. Thus, whether the charge carried by R217 is a sensing charge remains unclear.

Toward understanding the role of the Ci-VSP’s S4 arginines in voltage sensing, we performed a histidine scan according to the paradigm established for the voltage-gated, potassium-selective channel Shaker (Starace et al., 1997; Starace and Bezanilla, 2001, 2004). In the present study, we show that the charge located in position 217 does not participate in voltage sensing. Instead, this charge seems to bias the local membrane potential modulating the voltage dependence for sensing charge movement. Also, here we show that replacing R223 with a histidine enables a proton conductance at negative potential, indicating that this residue has simultaneous access to both the extracellular and intracellular space when the VSD is in the resting state. Finally, we show that histidines replacing the remaining arginines, namely R226, R229, and R232, can be titrated from the extracellular space when the sensor is in the activated state. These combined findings indicate that the arginines R223 through R232 cross the hydrophobic core of the VSD as a function of the membrane potential, implying that these residues are the sensing charge carriers of the S4 segment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mutagenesis and expression of Ci-VSP mutants

Ci-VSP mutants were generated by standard site-directed mutagenesis and verified by sequencing as described previously (Villalba-Galea et al., 2008). Mutations were introduced in Ci-VSP cloned in the vector pSD64TF (courtesy of Y. Okamura, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) carrying the mutation C363S. This mutation was introduced to eliminate catalytic activity (Murata et al., 2005).

For expression of Ci-VSP in Xenopus laevis oocytes, cDNA was linearized with XbaI and transcribed using an SP6 mMessage mMachine RNA polymerase kit (Ambion). Xenopus oocytes were injected with 50 nl of 0.5–1 µg/µl RNA and incubated at 16°C until used. The incubation solution (SOS) contained (mM) 100 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 2 Na-pyruvate, 0.050 EDTA, and 10 HEPES. The solution was titrated to pH 7.5 with NaOH.

Electrophysiology

Sensing currents were measured from oocytes 2–4 d after cRNA injection using the cut-open oocyte voltage clamp technique (Taglialatela et al., 1992; Stefani and Bezanilla, 1998) as described previously (Villalba-Galea et al., 2008). In brief, sensing currents were evoked by voltage steps (100–800 ms, 1–10-s intervals) from a holding potential (HP) of −60 to −90 mV to potentials ranging from −140 to 140 mV. Linear capacity currents were compensated analogically using the amplifier compensation circuit. The external recording solutions contained (mM) 100 N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMG), 2 CaCl2, and 100 of a pH buffer used as anion. The high concentration of buffer was used to tightly control pH. The buffers used for this study were HEPES for pH 7.4, MES for pH 5.0–6.5, and CHES for pH 9.0. The internal solution contained (mM) 100 NMG, 100 HEPES, and 2 EGTA. All solutions were titrated with methanesulfonic acid.

Electrophysiological data were acquired at 250 kHz, filtered at 100 kHz, and oversampled at 5–20 kHz for storage. Data acquisition and voltage protocol were performed using a custom-made program by C.A. Villalba-Galea using LabVIEW (National Instruments). Analysis was performed by a custom-made program by C.A. Villalba-Galea using Java (Oracle), and fits were performed in Origin (OriginLab).

Analysis

All experiments were performed at room temperature. Data are given as mean ± SD of the mean and value ± SE for fitted parameters.

Net-charge (Q) versus membrane potential (V) curves (Q-V curves) were generated by numerically integrating sensing currents (I) and plotting the values with respect to V. To quantify the voltage dependence of charge movement, Q-V curves were fit to a single two-state Boltzmann distribution, which is defined as follows:

where QMAX is the maximum net charge observed, zQ is the apparent charge of the VSD (also known as the slope of the distribution), V1/2 is the half-maximum potential at which Q(V) = QMAX/2, F is Faraday’s constant, R is the ideal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature. Q-V curves are usually normalized by QMAX for averaging.

The decay phase of sensing currents were fitted to a double exponential, and the weighted mean time constant was used to characterize the kinetics of sensing charge movement with respect to membrane potential. The weighted mean time constant (τON) was calculated as follows:

Where, Ai and τi are the amplitude and time constant of the i-th component.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows simultaneous fits of QON-V and τ-V for the mutants C363S, R217Q-C363S, and R217E-C363S. Fig. S2 shows assay of charge loss in the mutant R217Q-C363S at a pulsing frequency of 1–4 Hz. Fig. S3 shows fluorescence resonance energy transfer between fluorescent protein–tagged Ci-VSP constructs. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.201310993/DC1.

RESULTS

Our main goal was to identify what residues in the S4 segment function as carriers of charge that sense the difference in electric potential across the membrane. We refer to these charges as sensing charges. For this study, we were particularly focused on the five arginines found in the S4 segment of Ci-VSP. To date, three of these arginines have been regarded as a sensing charge, namely R217, R229, and R232 (Murata et al., 2005; Dimitrov et al., 2007; Kohout et al., 2008). However, a detailed description of the role of these residues in voltage sensing was yet to be provided.

We generated S4 segment arginine-to-histidine mutants and combined voltage pulse protocols and manipulation of the external pH (pHEXT) to probe whether these residues were able to access the extracellular milieu as a function of the membrane potential. Based on the work of Starace et al. (1997) and Starace and Bezanilla (2001, 2004), the underlying assumption was that sensing charge-carrying residues (sensing residues) are exposed to the intracellular space when the VSD is in the resting state and moved toward the extracellular side when the VSD is activated. If the replacing histidine was extracellularly exposed after activation, then decreasing the pHEXT would increase the probability for it to be protonated, increasing the total charge mobilized across the membrane during deactivation.

The approach described above was taken for all of the five arginines of the S4 segment. For residue R217, however, we first produced two additional mutants that neutralized or reversed the charge at this position. These mutations were studied to further understand the effects of mutating R217 on the voltage dependence of Ci-VSP.

R217 modulates the voltage dependence of Ci-VSP

Sensing currents were recorded from the mutants R217Q and R217E expressed in Xenopus oocytes using the cut-open voltage clamp technique (Taglialatela et al., 1992; Stefani and Bezanilla, 1998). These mutations were introduced using the catalytically inactive mutant (C363S) as background to avoid potential changes in the dynamic of the VSD caused by alteration in the concentration of phosphoinositides (Villalba-Galea et al., 2009; Kohout et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2012). For these recordings, the HP was set to −60 mV for C363S, −90 mV for R217Q, and −120 mV for R217E (Fig. 1 B). The net charge mobilized during activation (QON) was calculated by numerical integration of sensing currents (ON-sensing currents; ION) and plotted as a function of the membrane potential (V). The resulting plots, QON-V curves, were fitted to a single two-state Boltzmann distribution (see Materials and methods), and the fitted parameters were used to assess voltage dependence. For the mutant R217Q, the half-maximum potential (V1/2) was displaced −73 ± 0.9 mV with respect to the background construct, C363S; the charge-reverting mutation R217E added a further displacement of −51 ± 1.4 mV (Table 1). The zQ values showed a reduction of nearly 30% for the mutant R217Q with respect to the C363S. This could be interpreted as a reduction in the total sensing charge. However, the R217E mutant decreased only ∼15% with respect to C363S. This observation indicated that the decrease in zQ observed with the mutant R217Q may not be accounted for by the reduction in the total of sensing charges. This issue is discussed in detail below.

Table 1.

Fitted parameters of QON-V from R217 mutants

| Mutant | V1/2 | zQ | n |

| mV | |||

| C363S | 57 ± 0.4 | 1.56 ± 0.03 | 5 |

| R217Q-C363S | −16 ± 0.5 | 1.07 ± 0.02 | 3 |

| R217E-C363S | −67 ± 0.9 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 5 |

| R217H-C363S pH 6.1 | −13 ± 3 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 5 |

| 58 ± 1 | 1.60 ± 0.08 | ||

| R217H-C363S pH 7.4 | −14 ± 6 | 1.0 ± 0.04 | 5 |

| 28 ± 3 | 2.0 ± 0.6 |

When two values of V1/2 and zQ are given, the fit corresponds to a sum of two two-state Boltzmann functions.

Along with changes in voltage dependence, the R217 mutants also displayed faster ION when compared with C363S. To quantify the kinetic of ION, the decay phase of sensing current traces was fitted to a double exponential function, and a weighted mean time constant (τON) was calculated from the relative contribution of the times constants (see Materials and methods for details). Given the difference in voltage dependence between the R217 mutants, the τON was plotted as a function of the normalized net-charge (Q/QMAX). This type of plot uses the relative activity of the VSD as a reference, thus allowing us to compare the changes in the kinetics of activation of these mutants. The resulting τON-Q/QMAX curve showed that a common feature shared by the mutants is that τON sharply decreased when >75% of the charge was mobilized (Fig. 1 D). As estimated from the plots in Fig. 1 D, time constants observed when mobilizing half of the maximum net sensing charge (Q1/2) were 33 ms, 8 ms, and 6 ms for C363S, R217Q, and R217E, respectively (Fig. S1 B). Although these observations indicate that a positive charge in position 217 contributes to an increase in the energy barrier for the transition between the resting and active state of the VSD, it does not imply that R217 is a sensing charge.

Modulation of the voltage dependence by titration of R217H

If R217 carries a sensing charge, neutralizing it will decrease QMAX; adding the charge back will recover the initial value of QMAX. To implement this idea, R217 was replaced with a histidine on our common background construct C363S, producing the double mutant R217H-C363S, hereafter referred to as R217H. Titrating this histidine residue by decreasing the pHEXT will introduce a positive charge at position 217, which in turn should increase QMAX only if this residue carries a sensing charge.

Sensing currents were recorded from the mutant R217H expressed in oocytes. To assess whether the histidine in this position changed its accessibility when the voltage was modified, we first verified that, by manipulating the pHEXT, we were able to change the charge of the histidine in position 217 as indicated by a modulation of the voltage dependence of sensing currents. We observed that switching from pHEXT 7.4 to 6.1 slowed down ION (Fig. 2 A) at all potentials (Fig. 2 B). Yet, integration of ION yielded QON-V curves that were shifted around 24 mV toward more positive potentials at the half-maximum charge when pHEXT was changed from 7.4 to 6.1. This observation suggested that voltage dependence was shifted by the titration of the introduced histidine. To confirm that this effect was caused by the mutation, we recorded sensing currents from the background mutant C363S and found that the Q-V curves differed only in 7 ± 2.7 mV between pHEXT 7.4 ad 6.1 (Fig. 2 D). These results indicated that the modulation of voltage dependence by pHEXT was the consequence of introducing the mutation R217H. Furthermore, close inspection of the Q-V curves revealed the presence of two discernible components. Fitting the Q-V curves to a sum of two two-state Boltzmann distributions (Table 1) showed that the relative contribution of the more negative component to the total charge movement was 57 ± 3% (n = 5) and 75 ± 11% (n = 5) at pHEXT 6.1 and 7.4 (n = 5), respectively. The above observations suggested that the introduction of a histidine at position 217 gave rise to two populations of sensors, in which the histidine in position 217 is either protonated or not. Therefore, we concluded that protonation of R217H adds a positive charge at position 217.

Figure 2.

Mutant R217H. (A) Sensing currents from the mutant R217H-C363S at pHEXT 7.4 and 6.1. The HP for the recordings was −90 mV. After a 200-ms prepulse to −120 mV, test pulses ranged from −150 to 140 mV. (B) QON-V curves for the records in A. As shown, no changes were observed in the QON,MAX when pHEXT was modified. (C) Time constants versus potential (τ-V) curves display at least two components, where ON-sensing currents at pH 6.1 were slower than those observed at pH 7.4 at equivalent potentials. (D) QON-V curves for C363S at pHEXT of 7.4 and 6.1 were very similar to each other. In contrast, the mutant R217H displayed strong pHEXT sensitivity. QON-V were normalized to the QON,MAX observed at pH 7.4. No changes in QMAX were observed as a function of pHEXT. QON-V curves had two components and the relative proportion of them changed with pHEXT, where the component at more positive potential increases as pHEXT decreases (see Modulation of the voltage dependence by titration of R217H). Error bars are SD.

If both populations of VSDs, protonated and non-protonated, were independent, one would expect that the V1/2 values would remain unchanged and that pHEXT would modulate the relative contribution of these components. The expectation of independent VSD is supported by evidence suggesting that Ci-VSP is a monomeric protein (Kohout et al., 2008). Here, we found that, indeed, the V1/2 of the more negative component did not change as a function of the pHEXT. However, the more positive component shifted from 28 mV at pHEXT 7.4 to 58 mV at pHEXT 6.1. It could be claimed that this shift in voltage dependence is a consequence of changes in the charge of ionizable groups that bias the local electric field. However, our observations indicated that manipulating pHEXT does not affect voltage dependence for charge movement of the background construct (Fig. 2 D), indicating that the protonation of other residues does not affect voltage dependence. In addressing this conundrum, we rationalized that an intermediate V1/2 value of the more positive component at pHEXT 7.4 may arise from interactions between VSDs when Ci-VSP was expressed at high levels, as it is the case in this study. To explore this possibility, Ci-VSP constructs tagged with CFP and YFP were simultaneously expressed in oocytes. Analysis of the fluorescent emission spectra revealed that fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) occurred between these constructs, indicating that monomers were separated from each other by only few tenths of Angstroms (Fig. S3). Based on these results, we argue that when expressed at high density, monomers of Ci-VSP may cluster or segregate in small domains, leading to interactions between the VSD that may modulate voltage dependence, particularly at low pHEXT. Addressing this issue is beyond the scope of this study.

The total sensing charge was not affected by titration of R217H

To directly address whether a charged residue at position 217 contributes to the sensing of membrane potential, we quantified the maximum net charge observed as a function of pHEXT. One example is shown in Fig. 2 C, where it is clear that the absolute maximum charge is unaffected by histidine titration. To consider a large number of experiments, we normalized QON-V curves with respect to the QON,MAX obtained at pHEXT 7.4 (QON,MAX,pH7.4). The mean QON/QON,MAX,pH7.4-V curve revealed no changes in the normalized QON,MAX observed (Fig. 2 D). Therefore, we concluded that a charge at position 217 does not participate in the sensing of the electrical field across the plasma membrane.

The mutation R223H produces a proton current in the resting state

The next residue in the S4 segment of Ci-VSP is R223. Inconveniently, expression of the double mutant R223H-C363S was deleterious to the health of the oocytes: oocytes died or had membranes with very low resistance shortly after injection with mRNA. Arguably, this was caused by the translocation of protons mediated by the mutant. Because charge movement in Ci-VSP is observed at positive potential (Fig. 1), the histidine replacing R223 may have been dwelling in the hydrophobic core mediating proton translocation, which likely was deleterious for the oocytes’ well-being. Thus, we reasoned that shifting the voltage dependence of the VSD toward negative potentials would decrease the influx of proton at resting potential (about −20 mV when expressing the R223H mutant) and thus increase the rate of oocyte survival. Therefore, to overcome this problem, we introduced the mutation R223H on the background of the double mutation R217Q-C363S. It is important to remember that we showed here that R217 does not participate in voltage sensing. Therefore, this double mutant does not change the total number of gating charges, but shifts voltage dependence to more negative potential. This latter double mutant was used as background construct for all the remaining arginine-to-histidine mutants studied here.

Recordings from oocytes expressing the triple mutant R217Q-R223H-C363S, hereafter R223H, showed an inwardly rectifying conductance (Fig. 3 A) instead of sensing currents. This conductance was activated at potentials below −20 mV (Fig. 3 B). Also, decreasing the pHEXT increased the magnitude of the current. (Fig. 3 A). Furthermore, changing the pHEXT to 9.0 not only decreased the magnitude of the currents (Fig. 3 B), but also reverted the direction of the flow displaying a reversal potential (VREV) around −94 mV (Fig. 3 C). Because the predicted proton VREV was about −96 mV under our experimental conditions, we concluded the mutation R223H enabled a proton-selective conductance.

Figure 3.

Mutant R223H. (A) Current recorded from Xenopus oocytes expressing the mutant R217Q-R223H-C363S. The currents are likely carried by protons as their amplitude increases with the acidification of the external medium. HP was 40 mV, and test pulses ranged from −140 to 50 mV. (B) Current amplitudes at the end of the test pulse were normalized with respect to the end-of-the-step amplitude recorded at −100 mV and pHEXT 7.4. Current displays several-fold increase at pHEXT 6.0, while decreasing at pHEXT 9.0, when compared with currents recorded at pHEXT 7.4. Error bars are SD. (C) Normalization to the module of the maximum current at each potentials revealed that at pHEXT 9.0 (blue diamonds), the current reversed at potential around −90 mV, as expected if protons are the charge carriers.

These observations indicate that the electrical field across the VSD of Ci-VSP is likely focused in a narrow region, or “hydrophobic plug,” where at negative potentials the histidine replacing R223 dwells, bridging the passage of protons from the extracellular milieu to the interior of the cell. Furthermore, these results point out that, analogous to voltage-gated channels (Starace et al., 1997; Starace and Bezanilla, 2001, 2004; Asamoah et al., 2003; Long et al., 2007; Chakrapani et al., 2010), the VSD of Ci-VSP is likely to display water-filled crevices on both sides of the membrane, providing access to a hydrophobic plug.

R226H produces a current in the “up” state of the S4

The triple mutant R217Q-R226H-C363S, hereafter referred to as R226H, was also found to conduct protons. However, in contrast to the mutant R223H, no conductances were observed at very negative potentials when the sensor was in the resting state. Instead, a small sensing-like current was activated during depolarization (Fig. 4, A and C). In contrast, unambiguous currents were observed during repolarization, and their magnitude increased as the pHEXT decreased (Fig. 4). We could not discern what fraction of the transient currents observed during deactivation was carried by either protons or sensing charge. However, given the great increase in the amplitude of the current caused by decreasing pHEXT, these currents were most likely mediated by a proton conductance. To quantify the effect of the pHEXT, integration of the deactivating transient current yielded the net translocated charge (QOFF), which was plotted against the potential of the activating pulse (Fig. 4 B). The resulting QOFF-V curves from each individual experiment were normalized with respect to the corresponding maximum QOFF (QOFF,MAX) observed at pHEXT 6.0. Fitting the normalized QOFF-V curves to a two-state single Boltzmann showed that the voltage dependence of charge movement was shifted to more negative potential as the pHEXT was made more acidic (Table 2). The maximum normalized QOFF obtained from these fits were −0.037 ± 0.001 (n = 4), −0.575 ± 0.004 (n = 4), and −1.03 ± 0.006 (n = 4) for pHEXT 7.4, 7.0, and 6.0, respectively. These observations indicate that the histidine at position 226 was accessible from the extracellular side of the membrane after activation of the VSD.

Figure 4.

Mutant R226H. (A and B) Currents recorded from Xenopus oocytes expressing the mutant R217Q-R226H-C363S were evoked by applying test pulses ranging from −140 to 100 mV from an HP of −90 mV. Decreasing the pHEXT from 7.4 (A, top) to 6.0 (A, bottom) increased the amplitude of ITAIL. (B) Integration of ITAIL yielded QOFF that increased as the pHEXT decreased (see R226H produces a current in the “up” state of the S4 for details). (C) Leak-corrected ISTEP values show that in the active state, the VSD of the mutant R226H conducts protons, as revealed by the change in VREV as a function of pHEXT. Error bars are SD.

Table 2.

Fitted parameters of QOFF-V to a two-state Boltzmann function for the mutant R226H

| pHEXT | V1/2 | zQ | n |

| mV | |||

| 7.4 | −89 ± 7 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 4 |

| 7.0 | −30 ± 1 | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 4 |

| 6.0 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 4 |

After linear subtraction of leak current, the amplitude and reversal potential of the currents during the voltage step (ISTEP) depended on pHEXT (Fig. 4 C). The current amplitudes of traces from individual experiments were normalized with respect to the amplitude of the current recorded at the end of the 800-ms step to 0 mV at pHEXT 6.0. As shown in Fig. 4 C, increasing pHEXT shifted the VREV for the ISTEP toward negative voltages. The observed values for VREV were 50 ± 2 mV (n = 4) and −19 ± 3 mV (n = 4) at pHEXT 6.0 and 7.0, respectively. The VREV at pHEXT 7.4 could not be determined because of the small current amplitude of ISTEP at negative potentials. Nevertheless, the modulation of the VREV by pHEXT strongly suggests that the currents mediated by the mutant R226H are carried by protons. In addition, the values of VREV suggest that the expression of the mutant R226H had caused acidification of the oocyte cytosol. We surmise that this could be the cause for the rapid deterioration of oocytes after cRNA injection.

R229H produces an “up” state current

The possible involvement of the fourth charge in the S4 segment, R229, as a gating charge was assessed with transient currents recorded from oocytes expressing the triple mutant R217Q-R229H-C363S, mutant R229H hereafter. From an HP of −90 mV, these transient currents resembled sensing currents because they were observed right after the beginning of test pulses above −80 mV (Fig. 5 A) when the pHEXT was 7.4. At pHEXT 5.0, no transient currents were observed (Fig. 5 A, right). We argue that, like in the case of the mutant R217H (Fig. 2), decreasing pHEXT slows down charge movement; thus, sensing currents have very slow kinetics that cannot be resolved.

Figure 5.

Mutant R229H. (A) Currents recorded from Xenopus oocytes expressing the mutant R217Q-R229H-C363S were evoked by applying test pulses ranging from −120 to 80 mV. Test pulses were delivered from an HP of −90 mV. The amplitude of the current at the beginning of the test pulse decreased at pHEXT 5.0. The amplitude of the tail sensing currents increased as pHEXT decreased (red arrows). (B) Normalized ITAIL-V curves at pHEXT 7.4, 6.5, and 5.0. Currents from individual experiments were normalized with respect to the module of the maximum tail current observed at pHEXT 7.4. Normalized tail current (I/IMAX) increased 8 ± 2 as pHEXT decreased from 7.4 (left) to 5.0 (right). Error bars are SD.

In contrast, the amplitude of current observed during repolarization (tail currents, ITAIL; Fig. 5 B) increased as pHEXT was lowered. The amplitude of ITAIL after an 80-mV pulse was 8 ± 2 times larger at pHEXT 5.0 (n = 4) compared with pHEXT 7.4. These observations are consistent with the idea that these tail currents are carried by protons. However, we could not rule out the possibility that other ionic species could be conducted as well. As it was for the case of the mutant R226H, our data indicated that decreasing pHEXT increased the amplitude of the current enabled by the presence of a histidine replacing R229. Therefore, we conclude that R229H also participates in voltage sensing.

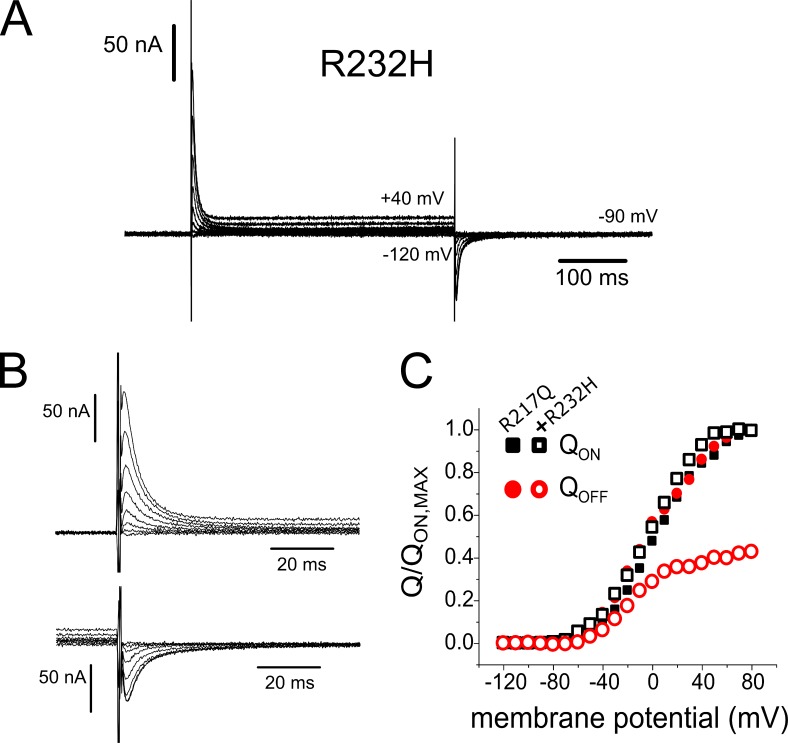

Charge loss by R232H deprotonation

To finalize our histidine scan of the S4 segment, we studied the possible participation of the fifth charge, R232, as a sensing charge using the triple mutant R217Q-R232H-C363S, hereafter R232H. Recording from oocytes expressing this construct did not exhibit any discernible conductance. Instead, we observed sensing currents (Fig. 6 A) that resembled those recorded from the background construct R217Q-C363S (Fig. 1 A). In spite of these similarities, we noticed that IOFF values from R232H were noticeably smaller than ION (Fig. 6 B). Integration of IOFF confirmed that QOFF was smaller than QON at all tested potentials (Fig. 6 C). The simplest explanation for this loss in sensing charge was that the histidine replacing R232 was deprotonated after activation. To test this hypothesis, we recorded currents from the background mutant R217Q and confirmed that no charge loss was observed in QOFF for this mutant (Fig. 6 C). Thus, we concluded that the loss of charge was related to the presence of the mutation R232H.

Figure 6.

Mutant R232H. (A) Sensing currents from the mutant R217Q-R232H-C363S evoked by 400-ms test pulses from −140 to 40 mV with an HP of −90 mV. Sensing current recordings were recorded at pH 7.4. (B) Detail of the ON- and OFF-sensing currents (ION and IOFF, respectively) from the record in A. (C) QON- and QOFF-V curves obtained from numerical integration of the ION (black open squares) and IOFF (red open circles) from the example shown in A. Solid symbols are for the QON (black solid squares)- and QOFF-V (red solid circles) curves for the mutant R217Q from an individual experiment. The fit to a single Boltzmann shows a V1/2 for the QON of −8 mV (error 1 mV) with a slope of 1.33 (error = 0.06). QOFF at 40 mV was 39% of QON,MAX.

We argue that the net loss of charge observed implies that after activation, the deprotonated state of histidine replacing R232 may be a more energetically favorable form of this residue and, therefore, effectively decreases the affinity (decreasing the pKa) of the histidine for protons. If this was the case, then increasing the concentration of protons should compensate for the decrease in affinity, mitigating the charge loss. To test this hypothesis, we recorded sensing currents at different pHEXT, calculated individual QON-V and QOFF-V curves, and normalized these curves with respect to QON,MAX (Fig. 7 A). The normalized mean QOFF,MAX values were 0.85 ± 0.08 (n = 4), 0.62 ± 0.14 (n = 5), and 0.43 ± 0.12 (n = 7) at pHEXT 6.5, 7.4, and 9.0, respectively. These observations clearly indicated that decreasing the pHEXT mitigated the loss of charge, as hypothesized.

Figure 7.

Charge loss at the OFF is pHEXT dependent. (A) Mean QON- and QOFF-V from individual experiments normalized with respect to QON,MAX at pH 7.4. Increasing pHEXT caused a larger loss of charge in QOFF (see Charge loss by R232H deprotonation for details). (B) QON,MAX values for individual experiments were normalized with respect to QMAX at pH 7.4 (QMAX,pH7.4), showing that the maximum QON net charge is independent of pHEXT. (C) pHEXT dependence of the V1/2 value of the QON. The slight shift of V1/2 by pHEXT is not significantly different (P < 0.05). (D) The pHEXT dependence of the apparent charge of the fitted Boltzmann distributions to the QON is not significant (P < 0.01). Error bars are SD.

Charge loss observed after activation

The results reported above also indicated that the histidine replacing R232 was accessible from the extracellular side of the membrane after activation. This suggested that charge loss may be caused by the translocation and eventual deprotonation once the histidine residue reaches the extracellular environment. As hypothesized above, the deprotonation may be caused by a change in the histidine’s Kd after activation. One implication of this idea is that the Kd is unaltered in the resting state and only the conformational changes associated with the activation of the sensor cause the decay in affinity for proton of the histidine. To address this idea, we next tested whether changing pHEXT affects QON,MAX. The values of QON,MAX obtained for each oocyte were normalized by the value of QON,MAX obtained at pHEXT 7.4 from the same oocyte. The means of normalized QON,MAX (QON,MAX/QON,MAX,pH7.4) were nearly equal to 1 at pHEXT 6.5 and 9.0 (Fig. 7 B). Therefore, changes in pHEXT do not alter the protonation status of the histidine at position 232 when the VSD is in the resting state. Furthermore, fitting the QON-V curves to a Boltzmann distribution revealed that the voltage dependence was almost unaltered, only shifting from 0 ± 6 mV (n = 4) at pH 6.5 to −10 ± 6 mV (n = 7) at pHEXT 9.0 (Fig. 7 C). The corresponding zQ values were unchanged as well, showing values ranging between 1.3 ± 0.2 and 1.4 ± 0.2 (Fig. 7 D).

Mutation R232H causes voltage sensor “trapping”

Thus far, we have found that histidine replacing four of the five native arginines was able to cross the hydrophobic plug of Ci-VSP as a function of the membrane potential. Yet, we were puzzled by the fact that deprotonation of R232H accounts for >55% of charge loss at pH 9.0. It was not immediately obvious why the removal of one of four charged residues sensing the membrane potential accounts for more than half of the total sensing charge. We reasoned that, in addition to the deprotonation of the histidine, the VSD may be “trapped” in a very stable state from which returning to the resting state was too slow for currents to be resolved with our recording setup.

To probe for the existence of a trapped state, we recorded sensing currents evoked by successive activating pulses. We reasoned that if activation is leading VSD into a trapped state, then successive activation will increase the number of VSDs trapped, thus decreasing the QON. To test this hypothesis, we recorded sensing currents evoked by trains of 25 250-ms pulses to 50 mV at 4 Hz. To minimize the contribution of deprotonation to the loss of charge, these recordings were performed at pHEXT 6.5. As proposed, pulsing at 4 Hz caused the largest decrease in ION amplitude (Fig. 8 A), reducing QON >50% after the 20th pulse (Fig. 8 B, black circles). Such reduction in QON was not observed with the background construct R217Q, which showed a mere 10% decay in QON only between the first and second pulse (Fig. 8 B, gray circles) and no further decrease during subsequent pulses. These combined observations led us to conclude that most of the charge loss observed with the mutant R232H is a consequence of the histidine mutation. In addition, no change in the decay time constant of ION was observed in the recording (Fig. 8 A), which is consistent with the idea that the charge decrease was caused by a reduction of the number of nontrapped sensors. Hence, we argue that the charge loss was caused by at least two processes: one was the fast initial deprotonation of R232H, and the second was a slow transition leading the VSD to a trapped state.

Figure 8.

Repetitive pulsing decreases QON. (A) From an HP of −90 mV, 80-ms test pulses were delivered at 4 Hz, causing a decrease in the amplitude of ON-sensing currents (ION). Recording was performed at pHEXT 6.5 to minimize charge loss by deprotonation. No changes in kinetics were detected (inset). (B) QON for the mutant R232H and R217Q were calculated by numerical integration of ION. A reduction of 54% in amplitude at the 25th pulse was observed for the R232H mutant, whereas a <10% decrease was observed for R217Q.

Voltage sensor trapping depends on activation frequency

Next, we reasoned that decreasing the frequency should decrease the magnitude of charge lost because increasing the period between activation pulses may allow a larger fraction of the VSD to return to the resting state. To address this idea, we performed recording at pulsing ranging from 0.1 to 2 Hz. As hypothesized, pulsing at 4 Hz caused the greatest decrease in QON, whereas pulsing at frequencies <1 Hz reduced QON by <10% (Fig. 9 A). To quantify the kinetics of trapping, QON values were normalized by the QON,MAX and plotted with respect to the number of trials (QON/QON,MAX trial plot; Fig. 9 A). Fitting QON/QON,MAX trial plots to a double exponential function yielded time constants for the fast initial phase that ranged from 6 ± 2 s (n = 5) at 0.2 Hz to 0.31 ± 0.03 s (n = 5) at 4 Hz (Fig. 9 B). Recording at frequencies of 1 Hz and above showed a slower component with time constants of 8 ± 1 s (n = 5) at 1 Hz and 1.7 ± 0.1 s (n = 5) at 4 Hz (Fig. 9 B). The relative contribution of both components to charge loss was also dependent on the pulsing frequency. At 4 Hz, the slow and fast components accounted for a fraction loss of 0.30 ± 0.01 and 0.20 ± 0.01 (n = 5), respectively (Fig. 9 C). It is noteworthy that no contribution of the slow component was observed when pulsing at frequency under 1 Hz. These observations are consistent with the idea that two components are the result of the existence of two distinct mechanisms causing the apparent loss of sensing charges.

Figure 9.

QON decreases as a function of frequency. (A) QON values were normalized with respect to the initial QON (QON,0) and plotted against the trial number, which were evoked at the frequency indicated on the right. The time course of the QON decay was fitted to two exponentials (red traces). (B) Fitted fraction of QON loss related to each component. The weight of the slow component increases as a function of pulsing frequency, whereas the fast component tended to saturate above 2 Hz. The slow component has no contribution at 0.5 Hz and lower frequencies. (C) Fitted time constants for the fast and slow components decrease exponentially as a function of frequency, with a tendency to saturate at about 2 Hz. Error bars are SD.

In the case of the mutant R217Q, pulsing at 4 Hz also reduced QON, but only by ∼10% (Fig. S2). This observation suggested that the slow component in the decay QON may be caused by VSD relaxation (Villalba-Galea et al., 2008; Villalba-Galea, 2012b). Thus, we speculate that the second component observed in the QON,QON,MAX trial curve of the R232H may be a relaxation-like process leading the VSD into a trapped state. Thus, the trapped state may be a stabilized form of the relaxed state of the VSD of Ci-VSP. This conjecture is currently being investigated.

DISCUSSION

Individual replacement of S4 arginines by histidine allowed us to assess the role of these residues in voltage sensing. Here, we found that R223, R226, R229, and R232 are carriers of sensing charges, whereas R217 is not. However, neutralization of this latter residue by replacing it with glutamine (mutant R217Q) shifts the voltage dependence of sensing currents >60 mV toward negative potentials, as shown previously (Villalba-Galea et al., 2008). Furthermore, reversing the charge with glutamate (R217E) caused an additional negative shift of −50 mV. These observations suggest that the charge in position 217 biases the voltage across the VSD. A similar effect was observed by neutralizing the most extracellular arginines in the putative S4 segment of the VSP isolated from Danio rerio, known as Dr-VSP. In this case, the neutralizing mutation R153Q causes a negative shift of over −80 mV for sensing charge movement (Hossain et al., 2008). In spite of this qualitative similarity, an intriguing outcome is that neutralization or charge reversion at R217 changed the fitted zQ values of the Q-V curves by 30% for R217Q and <15% for R217E, whereas R153Q decreased zQ by 60% for Dr-VSP (Hossain et al., 2008). Also, the kinetics of sensing currents recorded from the mutant R153Q were faster than those for the wild-type construct (Hossain et al., 2008). These combined observations may indicate that mutating R153 in Dr-VSP and R217 in Ci-VSP has a similar impact in the dynamic of the VSD, making them functionally equivalent in spite of the large difference on the effect over the zQ value.

On this latter issue, we would like to emphasize that changes in the zQ value are not a reliable way to measure sensing charge of a VSD. To illustrate this idea, let us consider the effect of the mutation I165R on the voltage dependence of Dr-VSP. In this case, it has been shown that increasing the number of charges in the S4 segment decreased the slope of Q-V curves (Hossain et al., 2008). The lack of correlation between the number of sensing charges and the zQ value has also been reported for Shaker. Recently, it was shown that mutation of noncharged residues of this voltage-gated channel can modify the steepness of the Q-V curve without altering the number of gating charges (Lacroix et al., 2012). In that study, it was shown that the total charge is mobilized in at least two stages, which may have distinct voltage dependences. Hence, the slope of the overall Q-V curve does not reflect the total sensing (gating) charge of the VSD (Lacroix et al., 2012).

Here, we have established that the zQ value may not be used to rule out R217 as a sensing charge. However, by the same token, this parameter cannot be used to establish whether a residue is a sensing charge either. Thus, to address this problem, we turned our attention to the mutation R217H, which allows us to manipulate the charge at position 217 by pH titration of the histidine residue. Contrary to other R217 mutants, QON-V curves of the mutant R217H clearly displayed two components that we identified as two populations of VSDs that differed in the protonation status of the 217 histidine. Particularly, one population had a more positive V1/2 when R217H was protonated; the other population had a more negative V1/2 because R217H was not protonated. However, the observation to be highlighted is that the overall Q-V curve showed no change in the QMAX regardless of the pHEXT (Fig. 2), implying that R217 is not a sensing charge of Ci-VSP.

Regarding the residues contained in the canonical every-third-residue array, all mutants were able to translocate protons across the plasma membrane. It is to be noted that the mutation R217Q clearly improves the quality of the oocytes’ health, presumably because of a shift in voltage dependence that helps shutting down the proton conductance at resting conditions. Our results indicate that, although the charge of the residue at position 217 is not a sensing charge, it has a strong impact on voltage dependence of charge movement. We hypothesize therefore that most of these changes in voltage dependence are the result of an electrical bias that affects the effective membrane potential.

In the case of R223H, this mutant conducted protons at negative potentials, when the VSD was in the resting state (Fig. 3). The recorded proton currents resembled those reported in the early 2000s involving arginine-to-histidine mutations in the potassium-selective, voltage-gated channel Shaker (Starace and Bezanilla, 2004). As shown in that study, replacing the first sensing arginine of this channel’s S4 segment (R362) enabled a proton-selective conductance in the resting state (Starace and Bezanilla, 2004). Given the qualitative similarity of the effects of these mutations in Shaker and Ci-VSP, we concluded that R223 is the first sensing charge in the S4 segment of Ci-VSP. Furthermore, this finding also indicates that the electrical field must be focused on a narrow hydrophobic region, similar to what has been described for Shaker (Starace and Bezanilla, 2004; Ahern and Horn, 2005).

Also similar to what has been shown before for Shaker (Starace et al., 1997; Starace and Bezanilla, 2001), the mutants R226H and R229H did not mediate a “down state” current. Instead, activation of the VSD evoked a small proton conductance (Fig. 4). We observed an increase in the QOFF carried during IOFF for the mutant R226H when pHEXT was decreased, suggesting that R226H resembles the mutant R371H of Shaker (Starace and Bezanilla, 2001). In contrast, the mutation R229H produced tail currents likely carried by protons when the VSD was activated. Tail current amplitudes increased when the extracellular side was acidified (Fig. 5). All of these findings are consistent with the existence of a narrow hydrophobic plug in the core of the VSD of Ci-VSP where the electric field is focused.

R232 is the most intracellular arginine of the S4 segment. Here, we found that in the R232H mutant the QOFF was smaller than QON at all potentials >0 mV. This observation suggests that, at positive voltages, the S4 segment moves toward the extracellular space, R232H passes the hydrophobic plug, and the maximum QOFF is decreased partially because of deprotonation of the histidine. The fact that the histidine in position 232 becomes accessible to the extracellular space is a strong indication that R232 is a sensing charge.

The impact of R232H on charge movement dynamics indicates that R232 is also involved in VSD relaxation. Repetitive activation of the VSD decreases QON. At 4 Hz, this decay occurs in two phases (Fig. 9). The first, fast, phase accounted for ∼20% of the charge lost, whereas the second, slow, phase added up to 30% to the loss of QOFF. The first phase seemingly involved deprotonation of the histidine at position 232. In contrast, the second phase may correspond to VSD relaxation. Our data suggest that conformational changes drive the VSD into a highly stable state. As a consequence, a fraction of the IOFF became too slow to be resolved in our recordings. Examples of this type of phenomenon have been described in voltage-gated channels. In particular, Shaker activation of the VSD causes an “immobilization” of gating charges related to relaxation of the VSD (Lacroix et al., 2011; Labro et al., 2012). It is possible that in VSP, the relaxed state may be stabilized by the histidine replacing R232. After deprotonation, a fraction of VSD is trapped; thus, sensing currents are slow and cannot be resolved. Consequently, successive pulsing to positive potentials evokes smaller current. As illustrated in Fig. 10, at negative potentials, the VSD dwells in the histidine-protonated resting state (RP). At more positive potentials, the VSD is driven to a protonated active state (AP). There the histidine releases a proton (AD). When the membrane potential is kept positive, a new transition leads to a trapped active state (AT). This transition may be driven by VSD relaxation. Polarizing the membrane to negative potentials will bring the VSD back to the RP state. The transition from an AD state to a resting deprotonated state (RD) will occur with a faster rate than the transition from the AT to the trapped resting state (RT). When the VSD is in the state AT, sensing charge movement is very slow. Thus, sensing currents are undetectable.

Figure 10.

Kinetic scheme to account for the charge loss in the mutant R232H. At negative potentials, the VSD dwells in the resting state (RP), where the residue R232H remains protonated (R232H-H+). Pulsing to more a positive potential promotes the transition to the active state (AP). From AP, the residue R232H can transit to a deprotonated active state (AD), becoming uncharged (R232H). If the membrane potential is returned to negative values, the fraction of VSD in the AP state can return to the RP state, whereas those in the AD state will return to deprotonated resting state (RD). If the membrane potential remains positive, a secondary transition will take place, leading the VSD to a locked active state (AT). This state is stable and transitions from it are infrequent, making this state a pseudo-absorbing state. Upon returning to negative potentials, a transition to a hypothetical locked resting state (RT) is expected. It assumed that transitions between these active states are voltage independent and so are those between resting states.

In summary, all arginine-to-histidine mutants except R217H were able to translocate protons across the membrane, suggesting that the structure of the VSD exhibits water-filled crevices penetrating the protein from both sides. Thus, as for voltage-gated channels (Starace and Bezanilla, 2004; Ahern and Horn, 2005), the electrical field is focused in a narrow hydrophobic region in the core of the VSD of Ci-VSP, modulating the energy barrier that the arginines must cross to act as sensing charges.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Diomedes E. Logothetis for his invaluable support to this project. Also, we would like to thank Drs. Louis J. De Felice and I. Scott Ramsey for their critical comments and discussions.

This work was supported through discretionary funds provided by the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at the Virginia Commonwealth University (to C.A. Villalba-Galea) and by National Institutes of Health grant GM030376 (to F. Bezanilla).

Edward N. Pugh Jr. served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- HP

- holding potential

- VSD

- voltage-sensing domain

- VSP

- voltage-sensitive phosphatase

References

- Ahern C.A., Horn R. 2005. Focused electric field across the voltage sensor of potassium channels. Neuron. 48:25–29 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah O.K., Wuskell J.P., Loew L.M., Bezanilla F. 2003. A fluorometric approach to local electric field measurements in a voltage-gated ion channel. Neuron. 37:85–97 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01126-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani S., Sompornpisut P., Intharathep P., Roux B., Perozo E. 2010. The activated state of a sodium channel voltage sensor in a membrane environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:5435–5440 10.1073/pnas.0914109107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov D., He Y., Mutoh H., Baker B.J., Cohen L., Akemann W., Knöpfel T. 2007. Engineering and characterization of an enhanced fluorescent protein voltage sensor. PLoS ONE. 2:e440 10.1371/journal.pone.0000440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guipponi M., Tapparel C., Jousson O., Scamuffa N., Mas C., Rossier C., Hutter P., Meda P., Lyle R., Reymond A., Antonarakis S.E. 2001. The murine orthologue of the Golgi-localized TPTE protein provides clues to the evolutionary history of the human TPTE gene family. Hum. Genet. 109:569–575 10.1007/s004390100607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaszovich C.R., Schreiber D.N., Oliver D. 2009. Ci-VSP is a depolarization-activated phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate 5′-phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 284:2106–2113 10.1074/jbc.M803543200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaszovich C.R., Leitner M.G., Mavrantoni A., Le A., Frezza L., Feuer A., Schreiber D.N., Villalba-Galea C.A., Oliver D. 2012. A human phospholipid phosphatase activated by a transmembrane control module. J. Lipid Res. 53:2266–2274 10.1194/jlr.M026021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.I., Iwasaki H., Okochi Y., Chahine M., Higashijima S., Nagayama K., Okamura Y. 2008. Enzyme domain affects the movement of the voltage sensor in ascidian and zebrafish voltage-sensing phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 283:18248–18259 10.1074/jbc.M706184200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H., Murata Y., Kim Y., Hossain M.I., Worby C.A., Dixon J.E., McCormack T., Sasaki T., Okamura Y. 2008. A voltage-sensing phosphatase, Ci-VSP, which shares sequence identity with PTEN, dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:7970–7975 10.1073/pnas.0803936105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout S.C., Ulbrich M.H., Bell S.C., Isacoff E.Y. 2008. Subunit organization and functional transitions in Ci-VSP. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:106–108 10.1038/nsmb1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout S.C., Bell S.C., Liu L., Xu Q., Minor D.L., Jr, Isacoff E.Y. 2010. Electrochemical coupling in the voltage-dependent phosphatase Ci-VSP. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6:369–375 10.1038/nchembio.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumánovics A., Levin G., Blount P. 2002. Family ties of gated pores: evolution of the sensor module. FASEB J. 16:1623–1629 10.1096/fj.02-0238hyp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa T., Takasuga S., Sakata S., Yamaguchi S., Horie S., Homma K.J., Sasaki T., Okamura Y. 2012. 3′ Phosphatase activity toward phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate [PI(3,4)P2] by voltage-sensing phosphatase (VSP). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:10089–10094 10.1073/pnas.1203799109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labro A.J., Lacroix J.J., Villalba-Galea C.A., Snyders D.J., Bezanilla F. 2012. Molecular mechanism for depolarization-induced modulation of Kv channel closure. J. Gen. Physiol. 140:481–493 10.1085/jgp.201210817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix J.J., Labro A.J., Bezanilla F. 2011. Properties of deactivation gating currents in Shaker channels. Biophys. J. 100:L28–L30 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix J.J., Pless S.A., Maragliano L., Campos F.V., Galpin J.D., Ahern C.A., Roux B., Bezanilla F. 2012. Intermediate state trapping of a voltage sensor. J. Gen. Physiol. 140:635–652 10.1085/jgp.201210827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Kohout S.C., Xu Q., Müller S., Kimberlin C.R., Isacoff E.Y., Minor D.L., Jr 2012. A glutamate switch controls voltage-sensitive phosphatase function. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:633–641 10.1038/nsmb.2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S.B., Tao X., Campbell E.B., MacKinnon R. 2007. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 450:376–382 10.1038/nature06265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y., Iwasaki H., Sasaki M., Inaba K., Okamura Y. 2005. Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature. 435:1239–1243 10.1038/nature03650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan W.J., Evsikov A.V., Okamura Y., Jaffe L.A. 2011. Voltage sensitive phosphoinositide phosphatases of Xenopus: their tissue distribution and voltage dependence. J. Cell. Physiol. 226:2740–2746 10.1002/jcp.22854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starace D.M., Bezanilla F. 2001. Histidine scanning mutagenesis of basic residues of the S4 segment of the shaker K+ channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 117:469–490 10.1085/jgp.117.5.469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starace D.M., Bezanilla F. 2004. A proton pore in a potassium channel voltage sensor reveals a focused electric field. Nature. 427:548–553 10.1038/nature02270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starace D.M., Stefani E., Bezanilla F. 1997. Voltage-dependent proton transport by the voltage sensor of the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 19:1319–1327 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80422-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani E., Bezanilla F. 1998. Cut-open oocyte voltage-clamp technique. Methods Enzymol. 293:300–318 10.1016/S0076-6879(98)93020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton K.A., Jungnickel M.K., Jovine L., Florman H.M. 2012. Evolution of the voltage sensor domain of the voltage-sensitive phosphoinositide phosphatase VSP/TPTE suggests a role as a proton channel in eutherian mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29:2147–2155 10.1093/molbev/mss083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taglialatela M., Toro L., Stefani E. 1992. Novel voltage clamp to record small, fast currents from ion channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Biophys. J. 61:78–82 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81817-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba-Galea C.A. 2012a. New insights in the activity of voltage sensitive phosphatases. Cell. Signal. 24:1541–1547 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba-Galea C.A. 2012b. Voltage-controlled enzymes: the new Janus Bifrons. Front Pharmacol. 3:161 10.3389/fphar.2012.00161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba-Galea C.A., Sandtner W., Starace D.M., Bezanilla F. 2008. S4-based voltage sensors have three major conformations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:17600–17607 10.1073/pnas.0807387105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalba-Galea C.A., Miceli F., Taglialatela M., Bezanilla F. 2009. Coupling between the voltage-sensing and phosphatase domains of Ci-VSP. J. Gen. Physiol. 134:5–14 10.1085/jgp.200910215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S.M., Downes C.P., Leslie N.R. 2001. TPIP: a novel phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase. Biochem. J. 360:277–283 10.1042/0264-6021:3600277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.