Abstract

BACKGROUND

Anxiety is a common and impairing problem in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). There is emerging evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) could reduce anxiety in children with high-functioning ASD.

OBJECTIVE:

To systematically review the evidence of using CBT to treat anxiety in children and adolescents with ASD. Methods for this review were registered with PROSPERO (CRD42012002722).

METHODS:

We included randomized controlled trials published in English in peer-reviewed journals comparing CBT with another treatment, no treatment control, or waitlist control. Two authors independently screened 396 records obtained from database searches and hand searched relevant journals. Two authors independently extracted and reconciled all data used in analyses from study reports.

RESULTS:

Eight studies involving 469 participants (252 treatment, 217 comparison) met our inclusion criteria and were included in meta-analyses. Overall effect sizes for clinician- and parent-rated outcome measures of anxiety across all studies were d = 1.19 and d = 1.21, respectively. Five studies that included child self-report yielded an average d = 0.68 across self-reported anxiety.

CONCLUSIONS:

Parent ratings and clinician ratings of anxiety are sensitive to detecting treatment change with CBT for anxiety relative to waitlist and treatment-as-usual control conditions in children with high-functioning ASD. Clinical studies are needed to evaluate CBT for anxiety against attention control conditions in samples of children with ASD that are well characterized with regard to ASD diagnosis and co-occurring anxiety symptoms.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, cognitive–behavior therapy, anxiety, children, adolescents, randomized controlled trial, meta-analysis

Kanner first described 45anxiety and excessive fearfulness in his initial account of autism.1 Anxiety disorders are frequently comorbid in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ranging from 40% to 84% for any anxiety disorder, 8% to 63% for specific phobias, 5% to 23% for generalized anxiety, 13% to 29% for social anxiety, and 8% to 27% for separation anxiety disorders.2–5 In addition to subjective distress, anxiety contributes to impairment in adaptive functioning6 and is among the primary reasons for mental health referrals in ASD.7 Therefore, the development and testing of effective treatments for anxiety in ASD is an important public health priority.

Community surveys indicate that 45% to 83% of children with ASD receive pharmacotherapy.8 Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in typically developing children with anxiety disorders,9 few drug studies have targeted anxiety in children with ASD.10–12 Results of a recent trial indicate that citalopram is not effective for repetitive behavior in youth with ASD.13 Atypical antipsychotics risperidone14,15 and aripiprazole16–18 have been reported to reduce irritability in children with ASD. However, side effects such as weight gain and metabolic abnormalities19 underscore the value of nonpharmacological treatments in ASD.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a first line of treatment for anxiety in typically developing children, and there is emerging evidence that CBT can be helpful for anxiety in children with ASD. In typically developing children with anxiety disorders, CBT has been evaluated in >40 randomized studies20 showing positive response in 50% to 60% of participants and moderate to large effect sizes (ESs) across studies.21 Theoretical underpinnings of CBT assume that pathologic anxiety is the result of an interaction between excessive physiologic arousal, cognitive distortions, and avoidance behavior.22 Accordingly, the core components of CBT include teaching emotion regulation skills aimed at reducing physiologic arousal and maladaptive thinking, followed by systematic exposure to feared situations to eliminate avoidant behavior. In clinical trials, separation and generalized anxiety disorders and social phobia are often grouped together because of the high degree of overlap in symptoms and the distinction from other anxiety disorders (eg, obsessive–compulsive disorder [OCD] and posttraumatic stress disorders).23,24 There is emerging evidence that given appropriate modifications, such as breaking anxiety management skills into concrete small steps, adding visual aids and written assignments, and giving a greater role to parents as coaches of new skills,25 CBT may be also helpful for reducing anxiety in children with high-functioning ASD. The purpose of this review was to systematically appraise the evidence for using CBT to treat anxiety in children and adolescents with higher-functioning ASD.

Method

Search Strategy to Identify Studies

We searched the electronic databases of Medline (1946–March Week 3, 2013), PubMed (March 19, 2013), PsycINFO (1967–March Week 3, 2013), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 2 of 12, February 2013) for relevant trials using search terms (and matching Medical Subject Headings) including “autism,” “Asperger,” “pervasive developmental disorder,” “behavior therapy,” and “cognitive-behavioral therapy.” In addition, we hand searched the references of appropriate papers for this study, as well as any appropriate review articles in this area for citations of additional relevant published and unpublished research. Details of the protocol for this systematic review, including a copy of the search strategy, were registered on PROSPERO (CRD42012002722).

Selection of Studies

Two reviewers independently evaluated the titles and abstracts of the located studies to determine eligibility for inclusion in this meta-analysis using the following criteria: (1) included patient population with a primary diagnosis of ASD, (2) compared a group of patients receiving CBT for anxiety with a group of patients in a control condition (eg, waitlist, treatment as usual [TAU]), and (3) included at least 1 standardized measure of anxiety. Case studies, single-case designs, and qualitative case reports were not considered for this meta-analysis. We did not have an inclusion criterion for the children’s level of cognitive functioning, but all studies included in this meta-analysis were conducted with subjects who had high-functioning ASD, defined as IQ above 70. No published studies to our knowledge have evaluated CBT in children with ASD and IQ below 70.

Variable Definitions and Coding

We coded 9 variables related to research methods, participant characteristics, treatment characteristics, and study results, which are shown in Table 1. For research methods, we coded the sample size, the type of control condition used (eg, waitlist control, no treatment control, alternative treatment), diagnostic assessments, outcome measures (as described below), and risk of bias, which was assessed by using the Jadad scale, which assigns a score of 1 to 5 based on a trial’s randomization, blinding, and attrition.26 For participant characteristics, we coded the mean age and gender distribution. For treatment characteristics, we extracted the format of CBT used in the study. For the ES, we calculated the standardized mean difference between posttreatment means of the treatment and comparison groups using Cohen’s d for each outcome category using Wilson’s ES calculators based on the formulas provided in Lipsey and Wilson (2001)27 and housed on the Campbell Collaboration web site (http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/resources/effect_size_input.php). All variables and ES estimates were double coded, and all discrepancies were resolved through mediation and, if necessary, a third opinion.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Trials of CBT for Anxiety in Children With High-Functioning ASD

| Source | Jadad Score | Participants | CBT Format | Control Condition | Diagnostic Assessment | Anxiety Outcome Measure | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sofronoff et al (2005) | 1 | N = 71, 65 boys, age range 10–12 y | 6 2-h group sessions of CBT with child only or with child and parent | Waitlist | Diagnosis of Asperger syndrome by pediatrician in community | SCAS-P | 0.10 |

| Chalfant et al (2007) | 2 | N = 47, 35 boys, mean age = 10.8 y, SD = 1.4 y, range 8–13 y | 12 2-h group sessions using the Cool Kids manual72 | Waitlist | Diagnosis of ASD by pediatrician, psychiatrist, or psychologist in community; ADIS-C/P | SCAS-P | 4.34 |

| SCAS-C | 2.69 | ||||||

| RCMAS | 3.34 | ||||||

| Wood et al (2009) | 3 | N = 40, 27 boys, mean age = 9.2 y, SD = 1.5 y, range 7–11 y | 15 90-min individual sessions using modular format73 | Waitlist | ADOS, ADI-R, WISC, ADIS-C/P | ADIS-C/P Clinical Severity Rating (blinded to treatment assignment) | 2.53 |

| MASC-P | 1.23 | ||||||

| MASC-C | 0.03 | ||||||

| Sung et al (2011) | 2 | N = 70, 66 boys, mean age = 11.2 y, SD = 1.8 y, range 9–16 y | 16 90-min group sessions using in-house curriculum | Social recreation | ADOS, WISC | SCAS-C | 0.07 |

| McNally Keehn et al (2012) | 3 | N = 22, 21 boys, mean age = 11.3 y, SD = 1.5 y, range 8–14 y | 16 90-min individual sessions using the Coping Cat manual74 | Waitlist | ADOS, ADI-R, WASI, ADIS-P | ADIS-P Interference Rating (blinded to treatment assignment) | 1.33 |

| SCAS-P | 0.95 | ||||||

| SCAS-C | 0.49 | ||||||

| Reaven et al (2012) | 2 | N = 50, 48 boys mean age = 10.4 y, SD = 1.7 y, range 7–14 y | 12 90-min group sessions using Face Your Fears curriculum75 | TAU | ADOS, WASI, SCARED | ADIS-P Clinical Severity Rating (blinded to treatment assignment) | 0.61 |

| Storch et al (2013) | 3 | N = 45, 36 boys, mean age = 8.9 y, SD = 1.3 y, range 7–11 y | 16 60- to 90-min sessions using the Behavioral Intervention for Anxiety in Children With Autism Program76 | TAU | ADOS, ADI-R, ADIS-C/P | PARS (blinded to treatment assignment) | 1.40 |

| ADIS-C/P Clinical Severity Rating (blinded to treatment assignment) | 0.91 | ||||||

| MASC-P | 0.49 | ||||||

| RCMAS | 0.37 | ||||||

| White et al (2013) | 3 | N = 30, 23 boys, mean age = 14.6 y, SD = 1.5 y, range 12–17 y | 13 75- to 90-min sessions of individual CBT plus 7 group sessions of social skills training77 | Waitlist | ADOS, ADI-R, WASI, ADIS-C/P | PARS (blinded to treatment assignment) | 0.33 |

| CASI anxiety scale | 0.38 |

ADI-R, Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised; ADIS-C/P, Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule–Child and Parent; ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; CASI, Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory; MASC-C, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children–Child; MASC-P, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children–Parent; PARS, Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale; and RCMAS, Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale; SCAS-C, Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale–Child Report; SCAS-P, Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale–Parent Report; SCARED, Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

Outcome Measures

The outcome measures for our analyses were standardized measures of anxiety. We found parent-, clinician-, and child-reported outcomes, which we analyzed separately for this review. Acceptable measures of parent-rated child anxiety included the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale–Parent Report,28 the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children–Parent,29 and the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory–4 ASD Anxiety Scale (CASI).30 Acceptable measures of clinician-rated child anxiety included the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS)31 and the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS).32 Acceptable measures of child- (self-) reported anxiety included the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale–Child Report,28 the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children–Child,29 and the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS).33

One study34 used 2 clinician-rated measures of anxiety (PARS and ADIS), and 1 study35 used 2 self-report measures of anxiety (RCMAS and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale [SCAS]). Because measures of anxiety are likely to be highly intercorrelated, we decided against averaging measures within categories. We included the PARS from the Storch et al34 study because this scale has been designed to measure severity of anxiety in clinical trials and it has been used as a primary outcome in the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study.9 We decided to include the SCAS from the Chalfant et al35 study because this measure has been a most commonly used self-report in studies of CBT for anxiety in ASD (see Table 1).

Meta-analytic Procedures

We estimated the difference between treatment and comparison conditions for each study by calculating the standardized mean difference ES. The ES estimate was calculated from the posttreatment scores and standard deviations provided in each study report. We chose the standardized mean difference ES over the weighted mean difference because multiple measures with different scales were used to assess the anxiety outcomes. We then combined results for the studies examining CBT separately for each informant (parent, clinician, and child) using 3 random effects meta-analyses with an inverse variance weighted mean ES. A random effects model was used as our primary synthesis metric for the meta-analysis because there was evidence of heterogeneity between the trials (eg, use of different treatment manuals, use of different outcome measures). We conducted separate meta-analyses for each outcome informant, which are shown in Figs 2, 3, and 4 for parent-rated anxiety, clinician-rated anxiety, and child-reported anxiety, respectively. Given the large variance in ESs across studies, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis by conducting a meta-analysis with the largest ES removed.36 Because recent criticism has been raised about the validity of the Q-statistic as a test of homogeneity in meta-analyses,37 we estimated heterogeneity for each study using I2, which estimates the proportion of between-study variance.38

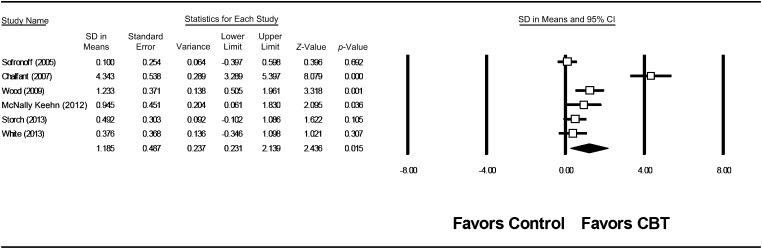

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of parent-rated anxiety random effects meta-analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of clinician-rated anxiety random effects meta-analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of child-rated anxiety random effects meta-analysis.

Results

Study Selection

We located 396 studies in our search. Eight studies34,35,39–44 involving 469 participants (252 treatment, 217 comparison) met our inclusion criteria and were included in the analyses. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses45 flow diagram of study selection is shown in Fig 1. The characteristics of the 8 included studies are shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA (Moher et al 2009) flow diagram of search.

Parent-Rated Anxiety

Six studies involving 251 children (141 treatment, 110 comparison) comparing CBT with waitlist or TAU for children with ASD included parent-rated anxiety outcome measures.34,35,39,40,42,43 As shown in Fig 2, CBT was superior to control conditions for anxiety symptoms in children with ASD as reported by the parents (random effects model ES = 1.19; 95% CI, 0.23 to 2.14; z = 2.44, P = .02; fixed effect model ES = 0.78). However, one study35 had an ES estimate (d = 4.34) that was much larger than that of the other studies (range, d = 0.10–1.23). We explored this effect by conducting a sensitivity analysis by removing the outlier, and we found that the estimated weighted mean ES would decrease from 1.19 to 0.57 (95% CI, 0.16 to 0.97; z = 2.73, P = .006) with the Chalfant et al study removed. We found a moderate degree of heterogeneity for the use of CBT on parent-rated anxiety, Q(5) = 54.8, P < .001; I2 = 91%. The heterogeneity with the Chalfant et al study removed for the Q-statistic was not statistically significant, but I2, though significantly lower, remained high, Q(4) = 7.46, P = .11; I2 = 46%.

Clinician-Rated Anxiety

Five studies involving 166 children with ASD (75 treatment, 91 comparison) comparing CBT with waitlist or TAU with clinician-rated outcomes were located.34,40–43 As shown in Fig 3, CBT was superior to control conditions for anxiety in children with ASD as reported by the clinicians (random effects model ES = 1.21; 95% CI, 0.50 to 1.97; z = 3.36, P = .001; fixed effect model ES = 1.10). Again, 1 study40 had an ES estimate (d = 2.53) that was much larger than that of the other studies (range, d = 0.33–1.40). We performed a sensitivity analysis to examine this effect by removing the Wood et al study and found a decrease in the estimated weighted mean ES from 1.21 to 0.89 (95% CI, 0.37 to 1.41; z = 3.37, P = .001). We found little heterogeneity for the use of CBT in clinician-reported anxiety, Q(4) = 17.8, P = .001; I2 = 77%. The heterogeneity with the Wood et al study removed for the Q-statistic was not statistically significant; although significantly lower, I2 remained high, Q(3) = 6.34, P = .10; I2 = 53%.

Child-Reported Anxiety

Five studies involving 175 children with ASD (90 treatment, 85 comparison) comparing CBT with waitlist, TAU, or social recreation control condition with child-reported outcomes were located.34,35,40,42,44 One study34 did not report the total score for the child-reported outcome (RCMAS), so we averaged all reported RCMAS subscales to calculate the ES estimate that was included in the meta-analysis. Figure 4 depicts a forest plot of the effect of CBT on child-reported anxiety. CBT for anxiety was not significantly different from control conditions as reported by the children (random effects model ES = 0.68 (95% CI, −0.17 to 1.54; z = 1.56, P = .12; fixed effect model ES = 0.48). Furthermore, this effect appears to be largely driven by 1 study,35 with an ES of 2.69 (ESs in other studies ranges from 0.03 to 0.49). We performed a sensitivity analysis by removing the Chalfant et al study and found that the estimated weighted mean ES decreased from 0.68. to 0.17 (95% CI, −0.13 to 0.47; z = 1.09, P = .27). We again found large heterogeneity, Q(4) = 34.67, P < .001; I2 = 88%, with all studies included, but not with the Chalfant et al study removed, Q(3) = 1.00, P = .80; I2 = 0%.

Publication Bias

Our final meta-analytic consideration was publication bias.46 A funnel plot is often used to detect publication bias, which can be analyzed visually. However, analysis of funnel plots with a small number of studies is not recommended because of the significant effects the addition of more studies can have.47 Therefore, we did not analyze publication bias using funnel plots, but given the large differences in ESs, we would expect additional research to have major effects on the results, thus indicating a strong possibility of publication bias. Given a possibility of publication bias, which we could not statistically examine because of the small number of studies, we also computed the fixed effect model for comparison, which is reported in the text but not shown in the figures.

Discussion

We located 8 randomized controlled studies evaluating CBT for anxiety in children and adolescents with ASD.34,35,39–44 Overall ESs on clinician- and parent-rated outcome measures of anxiety were d = 1.19 and d = 1.21, respectively, and in the large range. When the outlying studies were removed, the magnitude to these effects decreased to d = 0.57 for the parent ratings and d = 0.89 for the clinician ratings, but they remained statistically significant (ie, CBT was superior to control conditions). The magnitude of effects of CBT for anxiety relative to waitlist or TAU control conditions in children with ASD is similar to effects of CBT for anxiety in typically developing children.48,49 In contrast, most ES estimates of self-report of anxiety yielded small ESs, with 4 of 5 studies showing ES values less than 0.50 and 1 study showing an outlying ES of 2.69. The average d = 0.68 across the 5 studies was reduced to d = 0.19 when this outlier was removed. Based on these results, we conclude that parent ratings and clinician ratings of anxiety are sensitive to detecting treatment change with CBT for anxiety in children with high-functioning ASD. Although we found significant heterogeneity with all studies included, we deemed moderator analyses inappropriate because of the small number of studies involving mostly small sample sizes.

The difference in magnitude of ESs for clinician- and parent-rated anxiety relative to child self-report brings up a question of validity and reliability of anxiety measures in ASD. There is continuing debate among researchers as to whether anxiety in ASD is a true comorbidity or manifestation of core ASD symptoms.50 Thus, it is conceivable that it might be difficult for parents and clinicians who are asked to rate anxiety in children participating in CBT studies to distinguish anxiety from the core and associated symptoms of ASD. For example, “insistence on sameness” is tied to anxiety due to changes in routines; repetitive behaviors may be performed to reduce anxiety,51 and interruption of stereotyped behaviors often leads to anxiety.52 Two anxiety disorders, OCD and social phobia, may be difficult to diagnose because of their overlap with the core ASD symptoms of repetitive and stereotyped behaviors and impaired social interaction, respectively. Symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (ie, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and sleep problems) closely resemble common associated features of ASD. For example, children with OCD commonly have recurring, bothersome thoughts that are difficult to dislodge and distressing rituals that are often directed at removing contaminants or preventing harm. In contrast, children with ASD are less likely to have clearly identifiable obsessions and insight into the senseless nature of a compulsion.53 Repetitive and restricted behaviors tend to decrease in frequency with age and may be less severe in children with higher-functioning autism than in children with autism and intellectual disability.54 Nonetheless, some children with ASD, particularly higher-functioning children, can be diagnosed with OCD and may engage in repetitive behavior to reduce anxiety.51 Although it is often assumed that people with ASD are not interested in social contact, children with ASD may be aware of their social isolation and want it to be different. Awareness of social deficits and the legacy of failure in the social domain may amplify social anxiety in youth with higher-functioning forms of ASD.55–57 In turn, the presence of a co-occurring social anxiety disorder may compound social disability in autism. There is emerging evidence that anxiety disorders can be reliably diagnosed in children with ASD using structured psychiatric interviews.58 Positive response to CBT compared with waitlist and TAU control conditions on parent- and clinician-rated outcomes suggests that parents and clinicians can identify change in anxiety symptoms in children with ASD.

The magnitude of ESs on the child self-report of anxiety was small in 4 of 5 studies, with an average d = 0.19 after 1 outlying study was removed. In typically developing children with anxiety disorders, self-report of anxiety is also less sensitive to treatment change than parent and clinician ratings. For example, the average child self-report was d = 0.36 in 1 meta-analysis59 and d = 0.44 in the other.60 Regarding the discrepancy between parent and child reports of anxiety, it is noteworthy that cross-informant disagreements are a norm rather than the exception in assessment of child psychopathology.61,62 It is possible that children do not perceive their anxiety symptoms as being as troublesome as their parents do, which would attenuate the change in child self-report from pretreatment to posttreatment. Thus, parent ratings commonly reveal greater levels of anxiety in children with ASD than child self-reports.63,64 Alternatively, children may indeed perceive treatments as less helpful than their parents do. In the latter case, it is possible that CBT improves behaviors such as avoidance, a change that parents may interpret as reduction of anxiety but to a lesser extent than the subjective experience of distress that is reflected in self-report. Lastly, the utility of child self-report in children with ASD can be compromised by poor communication skills and cognitive impairment. However, because CBT requires verbal communication, only children capable of participating in verbal therapy were invited to participate in the studies included in this review. Furthermore, internal consistency coefficients of self-report of anxiety in children with high-functioning autism are commonly adequate.65 Although studies included in this meta-analysis did not estimate reliability of child self-reports in their samples, high levels of internal consistency were reported for these measures in other studies. Specifically, in children with high-functioning ASD the Cronbach α coefficients were 0.91 for the SCAS,66 0.92 for the MASC,65 and 0.88 for the RCMAS.67 Thus, it is unlikely that lack of change in child self-report of anxiety is caused by unreliability of child self-reports in ASD. Given that CBT for anxiety is a child-focused intervention that is conducted with the child and requires high levels of motivation and cooperation, child self-report of anxiety appears to be an important source of information about treatment success.

Regarding control conditions, 5 studies compared CBT for anxiety with waitlist, 2 with TAU, and 1 with an attention control condition (see Table 1). Because most children with ASD receive psychoeducational services or pharmacotherapy, subjects randomized to waitlist (as well as subjects randomized to CBT) were allowed to continue their ongoing treatments. Thus, we combined waitlist-controlled studies with studies that used TAU-controlled conditions because these 2 types of control conditions in studies of children with autism appear to be essentially the same. We note that there was considerable heterogeneity among the studies in describing concomitant treatments including providing no information,35,39 reporting a number of subjects receiving concomitant medication,41,43,44 and reporting medication, psychological, and school-based services.34,42 Careful characterization of concomitant treatments including medication and psychoeducational and behavioral interventions in future randomized controlled studies will enable estimating the effects of these concomitant treatments on the magnitude of response to CBT for anxiety.

Only one study compared CBT with an attention control condition that included age-appropriate social and recreational activities (eg, puzzles, treasure hunt) that were conducted in a group format by therapists who encouraged participation and adherence to group rules similar to that of CBT.44 There was no difference between CBT and the social recreation control conditions using child self-report measures of anxiety. However, this study was significantly limited by failure to evaluate the levels of the child’s anxiety before the beginning of the treatment, suggesting a possibility that many children in the study were not anxious. Careful evaluation of co-occurring anxiety symptoms and clear criteria for inclusion based on the presence and severity of anxiety are needed to enable interpretation of change after treatment. However, well-designed studies of CBT versus nonspecific treatment control conditions with children with ASD and clinically significant levels of anxiety are needed to evaluate whether reduction of anxiety is caused by CBT rather than attention from a therapist.

All studies reported using structured manuals to deliver CBT for anxiety and provided detailed descriptions of treatments in the method sections. Five treatment manuals have been published (referenced in Table 1) and can be used in clinical practice and dissemination and implementation studies. Most studies provided detailed descriptions of adaptations of CBT for children with ASD or included modules addressing the role of core ASD symptoms in the experience and expression of anxiety in ASD.40,68 Although comparison of session-by-session contents of these manualized interventions is beyond the scope of this meta-analysis, it is noteworthy that two studies did not use exposure exercises as part of their CBT interventions.39,44 Research with typically developing children and adults suggests that exposure to anxiety-provoking situations is a key component of CBT for anxiety.69 It is likely that exposure is also a necessary component of CBT for anxiety in children with ASD. Three studies also included large social skills components as part of treatment.34,40,43 Given the core impairment in social functioning and a possibility that anxiety and social deficits in ASD may be interrelated, combining CBT with social skills seems clinically relevant, and these studies support the feasibility of combined treatments. However, randomized studies with larger samples are needed to evaluate the relative contributions of these interventions. Alternatively, studies using single subject70 or dismantling designs71 can illuminate the relative effects of multiple behavioral interventions or techniques.

Despite these promising results, the research on CBT for anxiety in ASD has noteworthy methodological limitations in subject characterization, outcome assessment, and use of waitlist or TAU as a control condition. Two studies included children with a preexisting ASD diagnosis that was not confirmed by the study investigators,35,39 and 2 studies did not report whether children with ASD met criteria for co-occurring anxiety disorder or a cutoff for clinically significant levels of anxiety.35,44 Importantly, only 1 study used a matched active comparison control,44 but this study was also limited by the lack of a comprehensive anxiety assessment at baseline and reliance solely on child self-report of anxiety for outcome evaluation. It is possible that these limitations in subjects’ characterization have contributed to the wide range of ESs observed in this meta-analysis. These limitations can be addressed in the future studies of CBT for anxiety in ASD by using comprehensive assessment for subject characterization with regard to both ASD diagnosis and presence and severity of co-occurring anxiety, comparing CBT with well-designed and clinically relevant alternative treatment conditions that do not include elements of CBT, and reporting concomitant pharmacological, behavioral, and psychoeducational treatments that children receive as they participate in clinical trials.

The meta-analysis was also conducted on a small sample of studies with known methodological flaws; it is likely that the inclusion of additional studies would have significant impact on the results. Additional limitations of this review include the strong possibility of publication bias, which we tried to control for by providing meta-analytic results with 1 study removed, although to our knowledge the collection of randomized controlled trials of CBT for anxiety is the largest collection of a treatment technique for ASD other than that of secretin.

Conclusions

Eight randomized controlled studies of CBT for anxiety in children and adolescents with ASD were located and yielded significant effects of CBT relative to waitlist or TAU control conditions. Parent ratings and clinician assessments of anxiety but not child self-reports of anxiety were sensitive to treatment change. Future studies should evaluate CBT for anxiety against attention control conditions in samples of children with ASD that are well characterized with regard to ASD diagnosis and co-occurring anxiety symptoms.

Glossary

- ADIS-C

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule–Child Version

- ADIS-P

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule–Parent Version

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- CASI

Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory–4 ASD Anxiety Scale

- CBT

cognitive-behavior therapy

- ES

effect size

- OCD

obsessive-compulsive disorder

- PARS

Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale

- RCMAS

Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale

- SCAS

Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale

- TAU

treatment as usual

Footnotes

Dr Sukhodolsky contributed to the development of the review protocol, made decisions about eligibility, drafted the full review, and revised the manuscript; Dr Bloch contributed to the development of the review protocol, extracted and analyzed the data, and reviewed the manuscript; Ms Panza made decisions about eligibility, extracted and analyzed the data, and reviewed the manuscript; Dr Reichow contributed to the development of the review protocol, made decisions about eligibility, extracted and analyzed the data, and drafted the full review; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered with PROSPERO (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) (identifier CRD42012002722).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported in part by grants K01 MH079130 (Dr Sukhodolsky) and K23MH091240 (Dr Bloch). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr. Reichow receives royalties from an edited book on evidence-based treatments in autism; the other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Bruin EI, Ferdinand RF, Meester S, de Nijs PFA, Verheij F. High rates of psychiatric co-morbidity in PDD-NOS. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(5):877–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leyfer OT, Folstein SE, Bacalman S, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: interview development and rates of disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36(7):849–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muris P, Steerneman P, Merckelbach H, Holdrinet I, Meesters C. Comorbid anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 1998;12(4):387–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(8):921–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallett V, Lecavalier L, Sukhodolsky DG, et al. Exploring the manifestations of anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders [published online ahead of print February 2013]. J Autism Dev Disord. 10.1007/s10803-013-1775-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skokauskas N, Gallagher L. Mental health aspects of autistic spectrum disorders in children. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2012;56(3):248–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oswald DP, Sonenklar NA. Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(3):348–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2753–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag RJ, van der Hoeven J. Buspirone in the management of anxiety and irritability in children with pervasive developmental disorders: results of an open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):56–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Namerow LB, Thomas P, Bostic JQ, Prince J, Monuteaux MC. Use of citalopram in pervasive developmental disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(2):104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin A, Koenig K, Anderson GM, Scahill L. Low-dose fluvoxamine treatment of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders: a prospective, open-label study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33(1):77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King BH, Hollander E, Sikich L, et al. STAART Psychopharmacology Network . Lack of efficacy of citalopram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behavior: citalopram ineffective in children with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(6):583–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, et al. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network . Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(5):314–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/114/5/e634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus RN, Owen R, Kamen L, et al. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1110–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1533–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stigler KA, Diener JT, Kohn AE, et al. Aripiprazole in pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified and Asperger’s disorder: a 14-week, prospective, open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(3):265–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDougle CJ, Stigler KA, Erickson CA, Posey DJ. Atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(suppl 4):15–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seligman LD, Ollendick TH. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20(2):217–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, Albano AM, V, Weersing R, Curry J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):930–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendall PC. Guiding theory for therapy with children and adolescents. In: Kendall PC, ed. Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive–Behavioral Procedures. 3rd ed New York: Guilford; 2006:3–30 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: a randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(2):282–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(1):100–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moree BN, Davis TE., III Cognitive–behavioral therapy for anxiety in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders: modification trends. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2010;4(3):346–354 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spence SH. A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(5):545–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.March J. Manual for the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC). Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Gadow KD, et al. Parent-rated anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders: frequency and association with core autism symptoms and cognitive functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(1):117–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Child Version. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 32.RUPP Anxiety Study Group . The Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale (PARS): development and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1061–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I think and feel: a revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1978;6(2):271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Storch EA, Arnold EB, Lewin AB, et al. The effect of cognitive–behavioral therapy versus treatment as usual for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(2):132–142, e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chalfant AM, Rapee R, Carroll L. Treating anxiety disorders in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: a controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(10):1842–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-analysis. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S. A randomised controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(11):1152–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Har K, Chiu A, Langer DA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):224–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reaven J, Blakeley-Smith A, Culhane-Shelburne K, Hepburn S. Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: a randomized trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):410–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McNally Keehn RH, Lincoln AJ, Brown MZ, Chavira DA. The Coping Cat program for children with anxiety and autism spectrum disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(1):57–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, et al. Randomized controlled trial: Multimodal Anxiety and Social Skill Intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(2):382–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sung M, Ooi YP, Goh TJ, et al. Effects of cognitive–behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011;42(6):634–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. Publication Bias in Meta-analysis: Prevention, Assessment, and Adjustments. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sterne JAC, Becker BJ, Egger M. The funnel plot. In: Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Boernstein M, eds. Publication Bias in Meta-analysis: Prevention, Assessment, and Adjustments. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2005:75–98 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynolds S, Wilson C, Austin J, Hooper L. Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(4):251–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James A, Soler A, Weatherall R. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4(4):CD004690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerns CM, Kendall PC. The presentation and classification of anxiety in autism spectrum disorder. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2012;19(4):323–347 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: comparisons to mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volkmar F, Cook EH, Jr, Pomeroy J, et al. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(12 suppl. 1):32S–54S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruta L, Mugno D, D’Arrigo VG, Vitiello B, Mazzone L. Obsessive–compulsive traits in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(1):17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esbensen AJ, Seltzer MM, Lam KSL, Bodfish JW. Age-related differences in restricted repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(1):57–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bachevalier J, Loveland KA. The orbitofrontal–amygdala circuit and self-regulation of social–emotional behavior in autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(1):97–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bellini S. Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2004;19(2):78–86 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chamberlain B, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E. Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(2):230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ung D, Arnold EB, De Nadai AS, et al. Inter-rater reliability of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV in high-functioning youth with autism spectrum disorder [published online ahead of print March 27, 2013]. J Dev Phys Disabil. 10.1007/s10882-013-9343-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ishikawa SI, Okajima I, Matsuoka H, Sakano Y. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2007;12(4):164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silverman WK, Pina AA, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(1):105–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Los Reyes A, Youngstrom EA, Swan AJ, Youngstrom JK, Feeny NC, Findling RL. Informant discrepancies in clinical reports of youths and interviewers’ impressions of the reliability of informants. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(5):417–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101(2):213–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lopata C, Toomey JA, Fox JD, et al. Anxiety and depression in children with HFASDs: symptom levels and source differences. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(6):765–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Murray MJ, Ahuja M, Smith LA. Anxiety, depression, and irritability in children with autism relative to other neuropsychiatric disorders and typical development. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2011;5(1):474–485 [Google Scholar]

- 65.White SW, Schry AR, Maddox BB. The assessment of anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(6):1138–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Russell E, Sofronoff K. Anxiety and social worries in children with Asperger syndrome. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(7):633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mazefsky CA, Kao J, Oswald DP. Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2011;5(1):164–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sze KM, Wood JJ. Enhancing CBT for the treatment of autism spectrum disorders and concurrent anxiety. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2008;36(4):403–409 [Google Scholar]

- 69.McNally RJ. Mechanisms of exposure therapy: how neuroscience can improve psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(6):750–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sukhodolsky DG, Gorman BS, Scahill L, Findley DB, McGuire J. Exposure and response prevention with or without parent management training for children with obsessive–compulsive disorder complicated by disruptive behavior: a multiple-baseline across-responses design study. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(3):298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sukhodolsky DG, Golub A, Stone EC, Orban L. Dismantling anger control training for children: a randomized pilot study of social problem-solving versus social skills training components. Behav Ther. 2005;36(1):15–23 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lyneham HJ, Abbott MJ, Wignall A, Rapee RM. The Cool Kids Family Program: Therapist Manual. Sydney, Australia: Macquarie University; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wood JJ, McLeod BD. Child Anxiety Disorders: A Family-Based Treatment Manual. New York, NY: Norton; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kendall PC, Hedtke KA. Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy for Anxious Children: Therapist Manual, 3rd ed. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reaven J, Blakely-Smith A, Nichols S, Hepburn S. Facing Your Fears: Facilitator's Set. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wood JJ, Drahota A. Behavioral Intervention for Anxiety in Children With Autism. Los Angeles, CA: University of California–Los Angeles; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 77.White SW, Albano AM, Johnson CR, et al. Development of a cognitive–behavioral intervention program to treat anxiety and social deficits in teens with high-functioning autism. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13(1):77–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]