Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To describe the incidence, injury severity, resource use, mortality, and costs for children with gunshot injuries, compared with other injury mechanisms.

METHODS:

This was a population-based, retrospective cohort study (January 1, 2006–December 31, 2008) including all injured children age ≤19 years with a 9-1-1 response from 47 emergency medical services agencies transporting to 93 hospitals in 5 regions of the western United States. Outcomes included population-adjusted incidence, injury severity score ≥16, major surgery, blood transfusion, mortality, and average per-patient acute care costs.

RESULTS:

A total of 49 983 injured children had a 9-1-1 emergency medical services response, including 505 (1.0%) with gunshot injuries (83.2% age 15–19 years, 84.5% male). The population-adjusted annual incidence of gunshot injuries was 7.5 cases/100 000 children, which varied 16-fold between regions. Compared with children who had other mechanisms of injury, those injured by gunshot had the highest proportion of serious injuries (23%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 17.6–28.4), major surgery (32%, 95% CI 26.1–38.5), in-hospital mortality (8.0%, 95% CI 4.7–11.4), and costs ($28 510 per patient, 95% CI 22 193–34 827).

CONCLUSIONS:

Despite being less common than other injury mechanisms, gunshot injuries cause a disproportionate burden of adverse outcomes in children, particularly among older adolescent males. Public health, injury prevention, and health policy solutions are needed to reduce gunshot injuries in children.

Keywords: trauma, children, health services, violence

What’s Known on This Subject:

Gunshot injuries are an important cause of preventable injury and mortality in children, with emergency services often providing the initial care for patients. However, there is little recent population-based research to guide public health, injury prevention, and health policy efforts.

What This Study Adds:

Gunshot injuries are uncommon in children, but cause greater injury severity, need for major surgery, mortality, and costs compared with other injury mechanisms. There is also large variation in the population-adjusted incidence of pediatric gunshot injuries between regions.

Gunshot-related injuries are a leading cause of death and non-fatal injury among children and adolescents in the United States.1 Gunshot injuries rank second only to motor vehicle crashes as a cause of death for children ages 15 to 19 years.1 From 2001 through 2010, 29 331 children age 0 to 19 years died of gunshot-related injuries.1 Another 155 000 children were injured seriously enough to undergo treatment in emergency departments (EDs).1 After peaking in 1994, the gunshot-related mortality rate for children ages 0 to 19 years fell 54.6% by 2003, but has remained almost unchanged since.1

Pediatric gunshot-related injury and death has been the subject of several population-based epidemiologic studies from the mid-1980s through 2002.2–8 Other studies during this time period grouped gunshot injuries with other forms of intentional injury.9,10 More recent population-based research has been limited and focused exclusively on mortality11,12 or was restricted to hospital-based samples.13–15 Data from the National Violent Death Reporting System provide insight into the problem,16 although only include fatalities. Thus, there remains a lack of recent population-based research on gunshot-related injuries in children, with almost no studies evaluating or integrating the important role of emergency medical services (EMS) in the care of these patients.

To address these important research gaps, we conducted a population-based study of injured children served by EMS agencies in 5 regions of the western United States, matched to ED and hospital records. By using a large sample starting with 9-1-1 EMS contact, we compared children with gunshot injuries to those with other injury mechanisms regarding incidence, injury severity, hospital interventions, mortality, and costs.

Methods

Study Design

This was a multiregion, population-based, retrospective cohort study using the Western Emergency Services Translational Research Network (WESTRN). Eleven institutional review boards in 5 regions approved this protocol and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Study Setting

The study included injured children evaluated by 47 EMS agencies serving more than 2.2 million children17 in 5 regions and transporting to 93 hospitals (11 Level I, 5 Level II, and 77 non-tertiary community and private hospitals) over a 3-year period. The 5 regions included: Portland, OR/Vancouver, WA (4 counties); King County, WA; Sacramento, CA (2 counties); Santa Clara, CA (2 counties); and Denver County, CO. Each of these regions represents a predefined geographic “footprint” consisting of a central metropolitan area and surrounding areas (suburban and some rural), defined by EMS agency service areas.

Patient Population

We included all injured children up to age 19 years for whom the 9-1-1 EMS system was activated within the 5 predefined geographic regions from January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2008. Injured children were identified by provider primary impression in EMS patient care reports. Specifying the sample in this manner allowed us to identify a broad, population-based, out-of-hospital injury cohort of children served by EMS providers in multiple trauma systems. We excluded children transferred between hospitals without an initial presentation involving EMS and 9-1-1 calls without patient contact.

Variables

We recorded out-of-hospital variables from EMS electronic health records exported from each EMS agency and transmitted to a central data coordinating center. In regions where multiple EMS agencies (eg, fire departments and private ambulance agencies) care for the same patients, we matched EMS records at the patient level. We have previously detailed and rigorously evaluated the methods for constructing this cohort18 and have validated the all-electronic data collection processes used in this study.19

The primary exposure variable of interest was mechanism of injury (15 categories), as recorded by EMS providers. EMS agencies collected mechanism of injury based on standardized categories outlined in the National EMS Information System20 for “cause of injury.” The guidelines for collecting this variable in electronic patient care reports were based on standard EMS training and charting practices in these agencies. Because of small numbers of children in certain categories, we collapsed the mechanism variable into 6 categories: gunshot (including powder-charged and air guns), cut or piercing (eg, stabbing), occupant motor vehicle crashes, pedestrians struck by motor vehicles, falls, struck by blunt object (eg, assaults), and “other” mechanisms.

To evaluate the mechanism of injury term, we matched EMS chart narratives available from 2 sites (Portland, OR and Denver, CO) by using all available sources of EMS patient care reports (fire agencies, ambulance agencies, and base-hospital phone records transcribed from EMS calls). Chart narratives provide contextual descriptions of the scene, patient, and circumstances surrounding the injury event. We assessed inter-rater reliability by randomly sampling 20% of patients with non-missing values for mechanism and a matched chart narrative (n = 1915). An investigator blinded to the EMS-coded mechanism term abstracted these records for mechanism of injury by using the same categories. We then compared the 2 independent mechanism terms using κ scores, which ranged from 0.64 (“other” category) to 0.93 (motor vehicle occupant). In addition, we abstracted all available chart narratives for patients with gunshot injuries to estimate the proportion of injuries from powder-charged firearms versus air guns (including BB, pellet, and paint ball guns) in the sample.

We also collected out-of-hospital disposition, EMS transport mode, patient demographics (age, gender), field trauma activation status (a dichotomous measure of patients meeting predefined field trauma triage criteria), initial field physiologic measures (systolic blood pressure, Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score, respiratory rate), out-of-hospital procedures (intubation attempt, intravenous line placement), and transport destination (including hospital type). We categorized hospital destinations as major trauma centers (Level I and II trauma hospitals) based on their American College of Surgeons accreditation status and state-level designations versus non-tertiary hospitals. We also recorded the occurrence of inter-hospital transfer after initial EMS transport.

Outcomes

Hospital outcome measures included abbreviated injury scale (AIS) score, injury severity score (ISS), surgical interventions, blood transfusion, in-hospital mortality, and average per-patient acute care costs. To determine hospital outcomes, we matched EMS records to hospital records using probabilistic linkage (LinkSolv v8.2; Strategic Matching, Inc, Morrisonville, NY). Record linkage methodology has been used to link large EMS data files to hospital records in previous studies,21 validated for matching ambulance records to trauma registry data22 and rigorously evaluated in this database.18 Sources of electronic hospital records included local trauma registries, state hospital discharge databases, and state ED databases (3 sites did not have ED data available). Because AIS and ISS are not collected in state discharge or ED databases, we used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes and a mapping function (ICDPIC, Stata v 11; StataCorp, College Station, TX) to convert ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes to AIS and ISS values.23 Previous studies have validated the process of mapping administrative diagnosis codes to generate anatomic injury scores24,25 and we have previously validated ICDPIC-generated injury scores against chart-abstracted scores in this database.26 We defined “serious injury” as an AIS ≥3 in specific body regions and ISS ≥16 for overall injury severity.27 We categorized major surgical interventions by body region: abdominal, thoracic, spine, brain, neck, and vascular (including interventional radiology procedures). The methods for calculating per-patient acute care costs are described in the Supplemental Information; we did not evaluate costs beyond the acute care period.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the sample and compare children with gunshot injuries versus those injured by other mechanisms. We calculated annual incidence estimates by averaging the number of children injured by each mechanism over the 3-year period (numerator) and by using 2010 census data17 for each region to define the at-risk population of children (denominator).

To preserve the population-based sampling design and minimize bias in the analysis, we used multiple imputation28 to handle missing values for important out-of-hospital variables. These variables included mechanism of injury (13% missing), physiologic measures (16%–29% missing), and EMS procedures (3%–8% missing). Details on the use of multiple imputation in this study are included in the Supplemental Information. For analyses of hospital measures, we restricted the sample to children transported to acute care hospitals with matched hospital records available. As a sensitivity analysis, we recalculated estimates for hospital measures by using all transported children (matched and unmatched to hospital records) with multiple imputation to impute missing hospital outcomes. We managed the database and conducted analyses using SAS (v 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 49 983 injured children age 0 to 19 years were evaluated by EMS providers in the 5 regions over the 3-year period, of whom 505 (1.0%) had gunshot injuries. Among children with gunshot injuries, 421 (83.2%) were between age 15 and 19 years, and 427 (84.5%) were male. For children injured by other mechanisms (n = 49 478), 24 283 (49.1%) were between age 15 and 19 years, and 29 003 (58.6%) were male. Among children with gunshot injuries who had an EMS chart narrative available for review (n = 184, 36.4% of all children injured by gunshot), there were 27/184 (14.7%) air gun injuries, 156/184 (84.8%) firearm injuries, and 1/184 (0.5%) could not be determined. Children with gunshot injuries had greater out-of-hospital physiologic compromise, required more EMS medical procedures, had a higher proportion of deaths declared in the field, and had more field trauma activations, as compared with children injured by other mechanisms (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Injured Children Served by EMS in 5 Regions

| Children Injured by Gunshots; n = 505 (1% of total) | Children Injured by Non-Gunshot Mechanisms; n = 49 478 | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics (%) | ||

| 0–4 y | 5 (1.0%) | 7607 (15.4%) |

| 5–9 y | 16 (3.2%) | 6789 (13.7%) |

| 10–14 y | 64 (12.6%) | 10 799 (21.8%) |

| 15–19 y | 421 (83.2%) | 24 283 (49.1%) |

| Male | 427 (84.5%) | 29 003 (58.6%) |

| Regionsa | ||

| A | 26 (5.2%) | 3255 (6.6%) |

| B | 78 (15.4%) | 9675 (19.6%) |

| C | 108 (21.4%) | 10 587 (21.4%) |

| D | 160 (31.7%) | 17 857 (36.1%) |

| E | 133 (26.3%) | 8104 (16.4%) |

| Mechanism of injury (%) | ||

| Gunshot | 505 (100%) | — |

| Cut or pierce | — | 1262 (2.6%) |

| Struck by blunt object | — | 6224 (12.6%) |

| Fall | — | 11 942 (24.1%) |

| Motor vehicle crash | — | 14 357 (29.0%) |

| Pedestrian versus automobile | — | 1737 (3.5%) |

| Other | — | 13 956 (28.2%) |

| Out-of-hospital physiologic measures, procedures received, and triage statusb (%) | ||

| Age-adjusted hypotension | 58 (11.4%) | 2388 (4.8%) |

| GCS score 13–15 | 448 (88.7%) | 48 504 (98.0%) |

| GCS score 9–12 | 10 (2%) | 571 (1.2%) |

| GCS score ≤8 | 47 (9.3%) | 403 (0.8%) |

| Intubation attempt | 44 (8.6%) | 208 (0.4%) |

| Intravenous line placement | 321 (63.5%) | 9452 (19.1%) |

| Met ≥1 field trauma triage criteria | 276 (54.7%) | 7742 (15.7%) |

| Out-of-hospital disposition | ||

| Death in the field | 11 (2.2%) | 49 (0.1%) |

| No transport | 42 (8.2%) | 12 500 (25.3%) |

| Transport by ground ambulance | 451 (89.3%) | 36 469 (73.7%) |

| Transport by helicopter | 1 (0.2%) | 223 (0.5%) |

| Transport by law enforcement | 0 (0%) | 236 (0.5%) |

| Type of hospital, among children transported to an acute care hospital (n = 36 644)c | ||

| Level I trauma center | 330 (73.2%) | 14 434 (39.9%) |

| Level II trauma center | 66 (14.5%) | 3396 (9.4%) |

| Non-trauma hospital | 56 (12.3%) | 18 362 (50.7%) |

Raw counts of injured children by region; population-adjusted estimates are provided in Fig 1. Regions have been de-identified.

Hypotension was calculated as an initial out-of-hospital systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) <70 + (2 × age in years).

The total number of children transported to an acute care hospital excludes children transported by EMS to clinics, urgent care clinics, and other non-hospital facilities (n = 500) and patients transported by law enforcement (n = 236). Hospital type represents the final destination hospital, including 790 (2.1%) children with inter-hospital transfer after initial EMS transport (17 children injured by gunshots).

The population-adjusted annual incidence of children with gunshot injuries ranged from 1.9 to 30.9 per 100 000 by region (Fig 1A), a 16-fold difference. Older adolescents (age 15–19 years) had a higher incidence of gunshot-related injuries than younger children at all sites. Compared with other injury mechanisms, gunshot injuries had the lowest incidence (7.5 per 100 000 children) (Fig 1B). When stratified by age group, the incidence of gunshot injuries differed more by age group than any other injury mechanism (24.9 per 100 000 older adolescents versus 1.7 per 100 000 younger children).

FIGURE 1.

Age- and population-adjusted annual incidence of injuries among children served by 9-1-1 EMS in 5 regions (n = 49 983). A, Incidence of gunshot injuries in children, by region. B, Overall incidence of gunshot injuries versus other injury mechanisms.

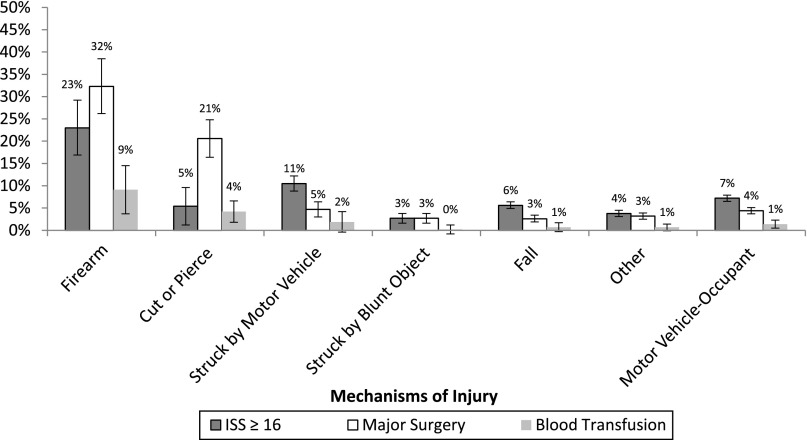

Among children transported by EMS with a matched hospital record available (n = 11 593, 31.6% of all children transported to an acute care hospital), there were differences in injury severity and hospital interventions by mechanism of injury (Fig 2). Compared with other injury mechanisms, children with gunshot injuries had the highest proportion of ISS ≥16 (23.0%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 17.6–28.4). When assessed by body region, gunshot injuries caused the greatest proportion of AIS ≥3 abdominal/pelvic injuries (15.4%, 95% CI 10.0–19.9) and extremity injuries (13.9%, 95% CI 9.6–18.3). Serious head injuries were similar between children injured by gunshot (9.0%, 95% CI 5.3–12.7) and those struck by motor vehicles (9.1%, 95% CI 6.8–11.3). The proportion of AIS ≥3 chest injuries was similar between those with gunshot injuries (14.5%, 95% CI 10.1–19.0) and cut/pierce injuries (16.9%, 95% CI 13.0–20.8). There were also differences in hospital interventions by injury mechanism, with children having gunshot injuries incurring the greatest proportion of major surgical interventions (32.3%, 95% CI 26.1–38.5) and blood transfusions (9.1%, 95% CI 5.5–12.7). Children with gunshot injuries commonly required abdominal (20.5%, 95% CI 15.3–25.7), thoracic (8.5%, 95% CI 4.9–12.1), and vascular (7.1%, 95% CI 3.9–10.3) surgery.

FIGURE 2.

Injury severity and major hospital interventions among children transported by EMS with hospital information available (n = 11 593).

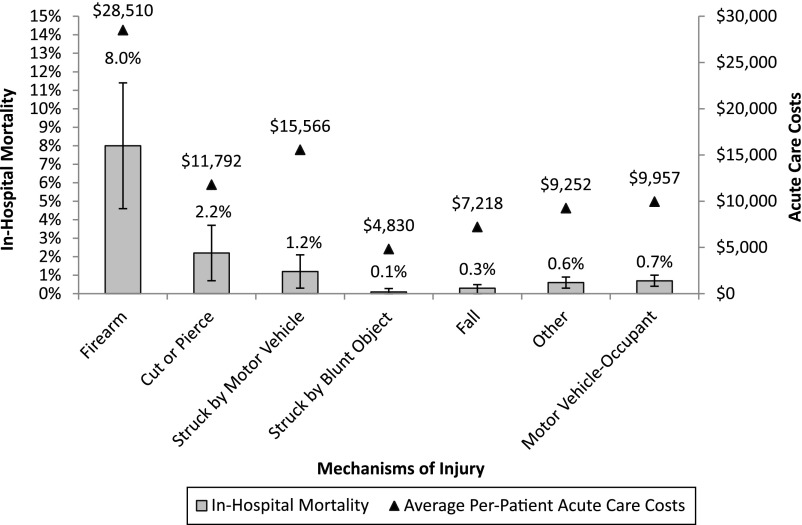

Figure 3 compares in-hospital mortality and acute care costs by mechanism of injury. In-hospital mortality for children with gunshot injuries (8.0%, 95% CI 4.7–11.4) was almost 4 times greater than the next highest group (cut/pierce, 2.2%, 95% CI 0.7–3.7). Among all 150 injured children who died (n = 60 declared in the field, n = 90 after transport), 32 (21%, 95% CI 15.1–28.8) died after gunshot injuries. The total number of injury deaths was exceeded only by motor vehicle occupant crashes (n = 53); however, in-hospital mortality for motor vehicle crashes (0.7%, 95% CI 0.5–1.0) was notably lower than for gunshot injuries. Total acute care costs followed a similar pattern, with children injured by gunshot incurring the highest average per-patient costs ($28 510, 95% CI 22 193–34 827). The mechanism group with the next highest cost was struck by a motor vehicle ($15 566, 95% CI 12 764–18 368).

FIGURE 3.

In-hospital mortality and total acute care costs among injured children transported by EMS with hospital information available (n = 11 593). (Acute care costs include EMS [both scene transport and inter-hospital transport], ED, and in-hospital costs.) Nineteen percent of hospital costs were imputed by using multiple imputation owing to cost information being unavailable in matched ED records.

Sensitivity analyses (in which missing hospital variables were imputed), including all children transported by EMS to an acute care hospital (n = 36 644), demonstrated similar comparisons between children with gunshot injuries versus other injury mechanisms (Supplemental Figs 4 and 5). However, point estimates for hospital metrics were slightly lower across all mechanisms, reflecting the inclusion of injured children discharged from the ED after EMS transport for whom no hospital record was available for linkage.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that gunshot injuries in children are uncommon, but are associated with a disproportionate burden of adverse outcomes compared with other injury mechanisms. Gunshot injuries were more severe, requiring more frequent major therapeutic interventions and resulting in higher mortality and per-patient costs than any other injury mechanism. Although gunshot injuries accounted for only 1% of injured children, they were associated with more than 20% of deaths after injury. The incidence of gunshot injuries also varied considerably between regions and age groups, with older adolescent males accounting for the majority of gunshot-related injuries.

Findings from this study are important for several reasons. There have been few population-based studies of children with gunshot injuries over the past decade. Similarly, gun research integrating the role of 9-1-1 emergency services has been limited. Our study involved both of these important elements. We demonstrate that one-third of children with an EMS response dying from gunshots are declared dead in the field and a substantive number are treated outside of major trauma centers, highlighting the limitations of previous research. Whereas previous studies have demonstrated the lethal nature of gunshot injuries in children,2–4,6–8,10,13–15 few have evaluated both out-of-hospital and in-hospital measures of injury severity, resource use, outcomes, and costs, compared with children injured by other mechanisms. These comparisons illustrate the immense per-patient impact of gunshot injuries in children. Even when compared with children injured by a cut/pierce mechanism (commonly grouped with gunshot injuries as “penetrating injury”), children with gunshot injuries were more severely injured and had notably higher mortality.

The frequency of gunshot injuries in children also differed widely by age group. Older adolescent males accounted for the majority of gunshot injuries and had substantially higher population-adjusted incidence rates compared with younger children. These findings suggest that injury prevention efforts to reduce gunshot injuries in children should begin at an early age, but focus particularly on older adolescent males.

Gunshot-related injury is a major public health issue for children. The low incidence and high burden of pediatric gunshot injuries suggests that more effective means to reduce such injuries must be strategic to have an impact. This pattern is in contrast to other injury mechanisms (eg, motor vehicle crashes) with high incidence and much lower per-patient injury burden. Lessons in improving child motor vehicle safety (eg, booster seats,29 age-appropriate restraint systems and seat position,30–32 air-bags33–36) and the associated reductions in pediatric motor vehicle mortality37 provide important examples of the potential impact of injury prevention efforts. The gains in motor vehicle safety required rigorous research to understand the problems, partnerships with national organizations (eg, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) and the automotive industry, and evidence-based legislation. Reducing gunshot injuries in children will likely require similarly broad-based, interdisciplinary efforts, in addition to rigorous research. Exploring the regional variation in pediatric gunshot injuries may also help direct injury prevention efforts, particularly in areas with disproportionately high rates of gunshot injuries among children.

We used a retrospective cohort study design, which can be limited by unmeasured confounding and bias. We attempted to minimize potential bias through population-based sampling from multiple EMS agencies, regions, and hospitals. Nevertheless, the robustness of our findings would be enhanced if replicated in larger prospective studies that include additional US cities. We attempted to maximize case ascertainment of injured children served by EMS and minimize bias in our incidence estimates through rigorous electronic data mechanisms18,19 and inclusion of EMS agencies with broad catchment areas. However, it is possible that some children with gunshot injuries did not have contact with EMS (eg, obvious death in the field without EMS involvement) or that certain children in our sample were non-residents of the geographic regions. Both of these factors could have affected our incidence estimates. Also, we did not have information about intent and therefore were unable to determine this important aspect of gunshot injuries to further delineate potential outcome differences.

Our estimates regarding the impact of gunshot-related injuries in children are conservative owing to several factors: (1) inclusion of children injured by powder-charged firearms and air guns in the “gunshot” category; (2) inclusion of children who died during hospitalization in the cost estimates, which could have suppressed costs due to the high mortality rate; (3) lack of long-term outcomes and years of productive life lost to fully quantify the costs borne by society; (4) use of ISS, which can underestimate the severity of injury from penetrating trauma38; and (5) lack of functional outcomes. Inclusion of these additional factors would further magnify the measurable impact of gunshot injuries in children. Also, our results do not include the intense emotional impact and life changes incurred by surviving parents, family members, and affected communities after the death of a child.

Data were missing for a portion of important variables (eg, mechanism of injury). Rather than excluding patients with missing out-of-hospital values (complete case analysis), we used multiple imputation to handle missing values, which has been shown to reduce bias39–44 and preserve the sampling design. Sensitivity analyses that included multiply imputed hospital values and different ways of coding patients’ missing mechanism of injury yielded qualitatively similar findings.

Finally, the categories used for mechanism of injury were completed by EMS providers, rather than hospital-based data abstractors. Although mechanism of injury was completed using standardized categories by on-scene providers who evaluated the patient and injury setting, it is possible that the assigned categories could have differed if completed by trained hospital data abstractors. Also, the electronic health record for most participating EMS agencies had a single field for mechanism of injury and therefore did not allow us to assess scenarios in which a patient may have had more than 1 injury mechanism.

Conclusions

We used a unique population-based cohort of injured children in 5 western US regions to demonstrate the disproportionate burden and adverse outcomes associated with gunshot injuries compared with other pediatric injury mechanisms. Although the relative incidence of gunshot injuries is low, the impact is large, particularly among older adolescent males.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank all the participating EMS agencies, EMS medical directors, trauma registrars, and state offices that supported and helped provide data for this project.

The WESTRN investigators are: Craig D. Newgard, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University; Eileen Bulger, MD, Thomas Rea, MD, MPH, Susan Stern, MD, Departments of Surgery and Medicine, Division of Emergency Medicine, Harborview Medical Center/University of Washington; Nathan Kuppermann, MD, MPH, James F. Holmes, MD, MPH, Deborah Diercks, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California at Davis; Renee Hsia, MD, MSc, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Francisco General Hospital/University of California at San Francisco; Kristan Staudenmayer, MD, N. Ewen Wang, MD, James Quinn, MD, Department of Surgery and Division of Emergency Medicine, Stanford University; Jason Haukoos, MD, MSc, Department of Emergency Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center/University of Colorado; N. Clay Mann, PhD, Erik Barton, MD, MS, MBA, Departments of Pediatrics and Surgery, Division of Emergency Medicine, University of Utah; Mark Langdorf, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California at Irvine; Sean Henderson, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles County/University of Southern California; Cameron Crandall, MD, David Sklar, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of New Mexico.

Glossary

- AIS

abbreviated injury scale

- CI

confidence interval

- ED

emergency department

- EMS

emergency medical services

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- ISS

injury severity score

- WESTRN

Western Emergency Services Translational Research Network

Footnotes

Dr Newgard conceptualized and designed the study, orchestrated funding for the project, conducted all database management and statistical analysis, critically evaluated all study results, drafted the initial manuscript, compiled and integrated all manuscript revisions, and takes full responsibility for the study; Dr Kuppermann assisted with study conceptualization and design, secured funding for the project, interpreted study results, provided leadership and guidance for the study group, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Holmes assisted with data acquisition, funding for the project, interpretation of study results, and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr Haukoos assisted with interpretation of study results and critical revision of the manuscript; Mr Wetzel assisted with data abstraction, interpretation of study results, and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr Hsia assisted with data acquisition, funding for the project, interpretation of study results, and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr Wang assisted with interpretation of study results and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr Bulger assisted with data acquisition, interpretation of study results, and critical revision of the manuscript; Drs Staudenmayer and Mann assisted with data acquisition, funding for the project, interpretation of study results, and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr Barton assisted with interpretation of study results and critical revision of the manuscript; Dr Wintemute assisted with study conceptualization and design, funding for the project, and content expertise, interpreted study results, provided leadership and guidance for the study group, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars Program; California Wellness Foundation (grant 2010-067); the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (grant UL1 RR024140); University of California Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center (grant UL1 RR024146); Stanford Center for Clinical and Translational Education and Research (grant 1UL1 RR025744); University of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science (grant UL1-RR025764 and C06-RR11234); and University of California San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute (grant UL1 RR024131). All Clinical and Translational Science Awards are from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The funding period for these grants was July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2010. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Available at: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed February 22, 2013

- 2.Eber GB, Annest JL, Mercy JA, Ryan GW. Nonfatal and fatal firearm-related injuries among children aged 14 years and younger: United States, 1993-2000. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1686–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiScala C, Sege R. Outcomes in children and young adults who are hospitalized for firearms-related injuries. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1306–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nance ML, Denysenko L, Durbin DR, Branas CC, Stafford PW, Schwab CW. The rural-urban continuum: variability in statewide serious firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(8):781–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell EC, Jovtis E, Tanz RR. Incidence and circumstances of nonfatal firearm-related injuries among children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(12):1364–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roesler J, Ostercamp M. Pediatric firearm injury in Minnesota, 1998. Fatal and nonfatal firearm injuries among Minnesota youth. Minn Med. 2000;83(9):57–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zavoski RW, Lapidus GD, Lerer TJ, Banco LI. A population-based study of severe firearm injury among children and youth. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2 pt 1):278–282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowd MD, Knapp JF, Fitzmaurice LS. Pediatric firearm injuries, Kansas City, 1992: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 1994;94(6 pt 1):867–873 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sege RD, Kharasch S, Perron C, et al. Pediatric violence-related injuries in Boston: results of a city-wide emergency department surveillance program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng TL, Wright JL, Fields CB, et al. Violent injuries among adolescents: declining morbidity and mortality in an urban population. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(3):292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nance ML, Carr BG, Kallan MJ, Branas CC, Wiebe DJ. Variation in pediatric and adolescent firearm mortality rates in rural and urban US counties. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):1112–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kegler SR, Annest JL, Kresnow M, Mercy J, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Violence-related firearm deaths among residents of metropolitan areas and cities—United States, 2006–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(18):573–578 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin CA, Unni P, Landman MP, et al. Race disparities in firearm injuries and outcomes among Tennessee children. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(6):1196–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schecter SC, Betts J, Schecter WP, Victorino GP. Pediatric penetrating trauma: the epidemic continues. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:721–725 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Senger C, Keijzer R, Smith G, Muensterer OJ. Pediatric firearm injuries: a 10-year single-center experience of 194 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(5):927–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karch DL, Logan J, McDaniel D, Parks S, Patel N. Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2009. MMWR. 2012;61(SS 6):1–43 [PubMed]

- 17.American fact finder—community facts. United States Census Bureau. Available at: http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml. Accessed February 1, 2013

- 18.Newgard CD, Malveau S, Staudenmayer K, et al. WESTRN investigators . Evaluating the use of existing data sources, probabilistic linkage, and multiple imputation to build population-based injury databases across phases of trauma care. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(4):469–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newgard CD, Zive D, Jui J, Weathers C, Daya M. Electronic versus manual data processing: evaluating the use of electronic health records in out-of-hospital clinical research. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(2):217–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uniform Pre-Hospital Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Dataset—Final Documentation and Data Dictionary. Version 2.2.1 (2006, last modified 4/9/2012). National Emergency Medical Services Information System. US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dean JM, Vernon DD, Cook L, Nechodom P, Reading J, Suruda A. Probabilistic linkage of computerized ambulance and inpatient hospital discharge records: a potential tool for evaluation of emergency medical services. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(6):616–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newgard CD. Validation of probabilistic linkage to match de-identified ambulance records to a state trauma registry. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(1):69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark DE, Osler TM, Hahn DR. ICDPIC: Stata Module to Provide Methods for Translating International Classification of Diseases (Ninth Revision) Diagnosis Codes Into Standard Injury Categories and/or Scores. Boston, MA: Boston College, Department of Economics; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Shankar BS, Turney SZ. An ICD-9CM to AIS conversion table: development and application. Proc AAAM. 1986;30:135–151 [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Shankar B. Classifying trauma severity based on hospital discharge diagnoses. Validation of an ICD-9CM to AIS-85 conversion table. Med Care. 1989;27(4):412–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fleischman RJ, Mann NC, Wang NE, et al. Validating the use of ICD9 codes to generate Injury Severity Score: the ICDPIC mapping procedure [abstract]. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(suppl):S314 [Google Scholar]

- 27.AAAM. The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), 2005 Revision, Update 2008. Des Plaines, IL: Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durbin DR, Elliott MR, Winston FK. Belt-positioning booster seats and reduction in risk of injury among children in vehicle crashes. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2835–2840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braver ER, Whitfield R, Ferguson SA. Seating positions and children’s risk of dying in motor vehicle crashes. Inj Prev. 1998;4(3):181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg MD, Cook L, Corneli HM, Vernon DD, Dean JM. Effect of seating position and restraint use on injuries to children in motor vehicle crashes. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 1):831–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durbin DR, Chen I, Smith R, Elliott MR, Winston FK. Effects of seating position and appropriate restraint use on the risk of injury to children in motor vehicle crashes. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/3/e305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahane CJ. Fatality Reduction by Air Bags—Analyses of Accident Data Through Early 1996. DOT HS 808 470. Washington, DC: NHTSA; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braver ER, Ferguson SA, Greene MA, Lund AK. Reductions in deaths in frontal crashes among right front passengers in vehicles equipped with passenger air bags. JAMA. 1997;278(17):1437–1439 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cummings P, Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, McKnight B, Mack C. Air bags and passenger fatality according to passenger age and restraint use. Epidemiology. 2002;13(5):525–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newgard CD, Lewis RJ. Effects of child age and body size on serious injury from passenger air-bag presence in motor vehicle crashes. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1579–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration Traffic Safety Facts 2010 Data, Children. DOT HS 811 641. Washington, DC: US Dept of Transportation; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavoie A, Moore L, LeSage N, Liberman M, Sampalis JS. The New Injury Severity Score: a more accurate predictor of in-hospital mortality than the Injury Severity Score. J Trauma. 2004;56(6):1312–1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Heijden GJMG, Donders ART, Stijnen T, Moons KGM. Imputation of missing values is superior to complete case analysis and the missing-indicator method in multivariable diagnostic research: a clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(10):1102–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crawford SL, Tennstedt SL, McKinlay JB. A comparison of anlaytic methods for non-random missingness of outcome data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(2):209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joseph L, Bélisle P, Tamim H, Sampalis JS. Selection bias found in interpreting analyses with missing data for the prehospital index for trauma. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(2):147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(12):1255–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newgard CD. The validity of using multiple imputation for missing out-of-hospital data in a state trauma registry. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(3):314–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newgard CD, Haukoos JS. Advanced statistics: missing data in clinical research—part 2: multiple imputation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):669–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bazzoli GJ, Kang R, Hasnain-Wynia R, Lindrooth RC. An update on safety-net hospitals: coping with the late 1990s and early 2000s. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(4):1047–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corso P, Finkelstein E, Miller T, Fiebelkorn I, Zaloshnja E. Incidence and lifetime costs of injuries in the United States. Inj Prev. 2006;12(4):212–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacKenzie EJ, Weir S, Rivara FP, et al. The value of trauma center care. J Trauma. 2010;69(1):1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Consumer Price Index. Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor. Available at: www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed February 22, 2013

- 49.Raghunathan T, Lepkowski, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27:85–95 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.