Abstract

Bevacizumab is a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody able to produce clinical benefit in advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients when combined to chemotherapy. At present, while there is a rising attention to bevacizumab-related adverse events and costs, no clinical or biological markers have been identified and validated for baseline patient selection. Preclinical findings suggest an important role for myeloid-derived inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils and monocytes, in the development of VEGF-independent angiogenesis. We conducted a retrospective analysis to investigate the role of peripheral blood cells count and of an inflammatory index, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), as predictors of clinical outcome in NSCLC patients treated with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy. One hundred twelve NSCLC patients treated with chemotherapy ± bevacizumab were retrospectively evaluated for the predictive value of clinical or laboratory parameters correlated with inflammatory status.

Univariate analysis revealed that a high number of circulating neutrophils and monocytes as well as a high NLR were associated with shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in bevacizumab-treated patients only. We have thus developed a model based on the absence or the presence of at least one of the above-mentioned inflammatory parameters. We found that the absence of all variables strongly correlated with longer PFS and OS (9.0 vs. 7.0 mo, HR: 0.39, p = 0.002; and 20.0 vs. 12.0 mo, HR: 0.29, p < 0.001 respectively) only in NSCLC patients treated with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy.

Our results suggest that a baseline systemic inflammatory status is marker of resistance to bevacizumab treatment in NSCLC patients.

Keywords: monocytes, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, lung cancer, inflammation, bevacizumab, neutrophils, angiogenesis

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the first leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Standard treatment of advanced disease is based on the combination of a platinum-derivative with a second drug such as gemcitabine, paclitaxel, pemetrexed, docetaxel or vinorelbine1-5. Advanced NSCLC patients however, despite the treatment, have a median overall survival (OS) of about 10 mo.6 More recently, the efficacy of standard combination-chemotherapy has been improved by the introduction of anti-EGFR agents (in selected patients) and bevacizumab, an anti-angiogenic humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) IgG1 to the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).7 Two phase III trials showed the efficacy of this drug in non-squamous NSCLC patients8-10; however, the use of this mAb is burdened by adverse events and unnecessary costs. A survival benefit was showed in the pivotal Sandler trial where bevacizumab was combined to carboplatin/paclitaxel doublets but not in the AVAIL trial when it was combined to cisplatin and gemcitabine. Furthermore, no clinical or biological markers for selection of patients, who may benefit from bevacizumab-based treatments, are presently available.

Our research was based on pre-clinical and clinical findings on the inflammation-mediated cross-link between endothelial cells and innate immune system effectors11-13 which has been proposed to play a critical role in the resistance to antiangiogenic treatments. In particular, inflammatory cells that enrich tumor micro-environment trigger tumor progression and escape from immune system, as well as they induce a VEGF-independent angiogenesis.14 On these results, we hypothesized that changes in the systemic inflammatory status, measured trough peripheral blood cell counts and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), may reflect changes in tumor inflammatory microenvironment, providing useful information on the potential activation of alternatives pathways of angiogenesis which may account for impairment of bevacizumab activity.

We conducted a retrospective study with the purpose of investigating the role of peripheral lymphocyte, neutrophil, monocyte and platelet counts and of an inflammatory index, the NLR, as predictors of the clinical outcome of NSCLC patients treated with bevacizumab in addition to first-line platinum based combination chemotherapy.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

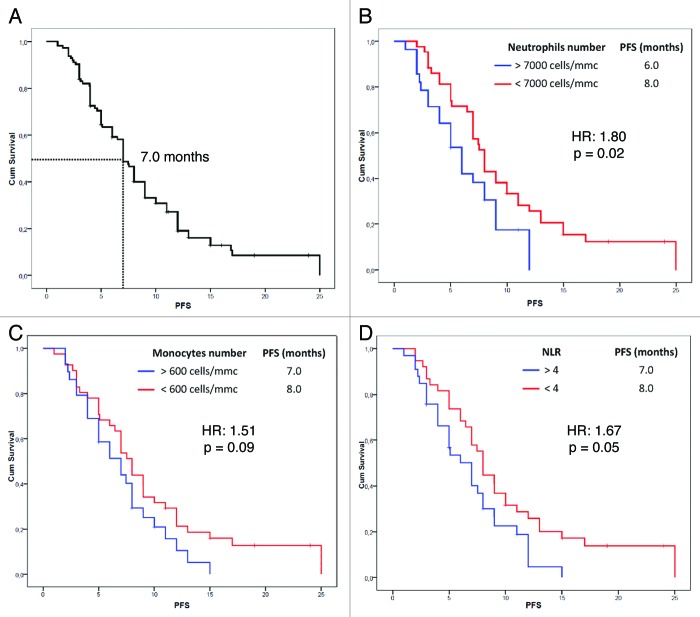

Patients’ characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. A total of 112 patients were included in our study (median age 62 ± 11 y; male 72%). 73 received a standard platinum-based doublet plus bevacizumab, while 39 received the platinum-based chemotherapy alone and were used as a calibration arm. No significant differences were observed between baseline characteristics of two groups. Median follow-up time was 15 mo. We observed a RR of 66.7% and 45.2% and a disease control rate (DCR) of 88.9% and of 71% for the bevacizumab group and the group respectively. The median PFS of the whole group was 7 mo (95% CI: 6.17–7.82 mo) (Fig. 1A), while the median OS was 15 mo (95% CI: 13.23–16.77 mo). PFS and OS were not significantly different between the bevacizumab and the control group.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| CHT+BEV (n = 73) | Control group (n = 39) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Age (mean ± SD), years |

58.57 ± 10.54 |

67.85 ± 9.67 |

|

Sex (male/female), % |

75/25 |

67/33 |

|

ECOG (median) |

0 |

0 |

|

Histology (Ad/Sq/Und)% |

79.5/15.1/5.5 |

79.5/12.8/7.7 |

|

Neutrophil counts (mean ± SD/mm3) |

6400 ± 2800 |

5800 ± 2000 |

|

Lymphocyte counts (mean ± SD/mm3) |

1900 ± 1300 |

1800 ± 990 |

|

Monocyte counts (mean ± SD/mm3) |

560 ± 270 |

540 ± 260 |

|

Platelets counts (mean x 103 ± SD/mm3) |

285 ± 102 |

276 ± 105 |

| NLR (mean ± SD) | 4.62 ± 3.97 | 3.78 ± 1.96 |

Figure 1. Progression free survival estimation of the whole group (A) and according to baseline neutrophil (B) and monocyte (C) count and NLR value (D) in NSCLC patients treated with bevacizumab.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

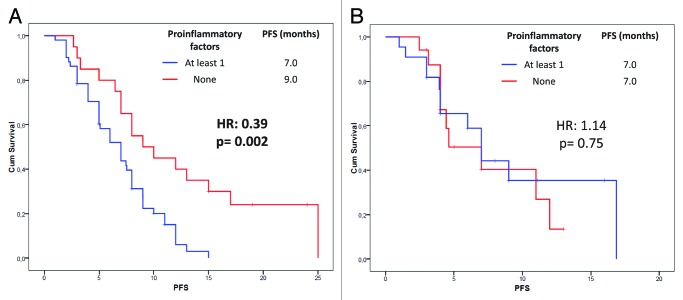

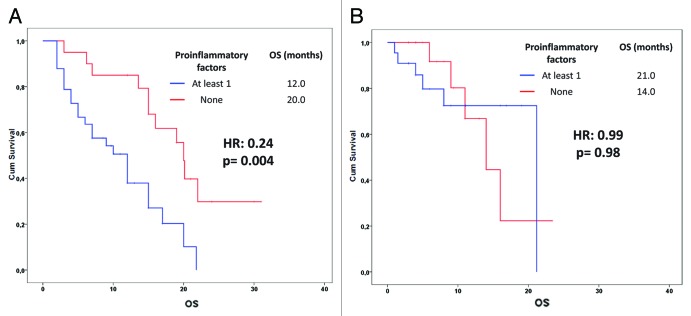

We analyzed the effect of the above mentioned 8 potential prognostic variables on PFS (Table 2). In our analysis, patients with a basal neutrophil count lower than 7000 cells/mm3 (p = 0.02) (Fig. 1B), a monocyte count lower than 600 cells/mm3 (p = 0.09) (Fig. 1C) and a NLR lower than 4 (p = 0.05) (Fig. 1D) experienced longer PFS only in the bevacizumab group. Furthermore, we found a significant association between a lymphocyte count lower than 1700 cells/mm3 at baseline and a worse response to chemotherapy (p = 0.02) (data not shown). On these findings, we developed a predictive model in which NSCLC patients were divided into two subgroups according to the absence or the presence of at least one of the above mentioned variables associated with better survival in the bevacizumab group. The absence of pro-inflam matory factors was significantly associated with better PFS in the bevacizumab group only (9.0 vs. 7.0 mo; HR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.20–0.74; p = 0.002) (Fig. 2). In the multivariate analysis (using forward stepwise model) only the absence of “pro-inflammatory” factors continued to be significantly related to PFS (HR: 0.29, 95% CI: 0.12–0.70; p = 0.006) in the bevacizumab group but not in the control group. Furthermore, we investigated our model on OS prediction (Fig. 3). Again, the same variable was highly correlated with a better OS in the bevacizumab group only, regardless the short follow-up period. In the multivariate analysis (using forward stepwise model) only the absence of “pro-inflammatory” factors remained significantly associated with OS (20.0 vs. 12.0 mo; HR: 0.24, 95% CI: 0.09–0.63; p = 0.004).

Table 2. Univariate analysis.

| Variables | BEV group | Control group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

PFS |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

PFS |

HR (95% CI) |

p value |

||

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| < 65 y |

7.0 |

0.68 (0.36–1.29) |

0.25 |

4.4 |

0.74 (0.31–1.77) |

0.48 |

||

| > 65 y |

8.0 |

7.0 |

||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| F |

7.0 |

0.83 (0.33–2.07) |

0.72 |

7.0 |

0.90 (0.51–1.61) |

0.68 |

||

| M |

7.9 |

6.0 |

||||||

|

Histology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Ad |

8.0 |

0.93 (0.59–1.47) |

0.85 |

6.0 |

0.93 (0.46–1.89) |

0.90 |

||

| Sq |

7.0 |

11.0 |

||||||

| Und |

2.0 |

9.0 |

||||||

|

Neutrophil counts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| < 7000 cells/mm3 |

8.0 |

1.80 (1.06–3.07) |

0.02 |

9.0 |

1.49 (0.57–3.85) |

0.39 |

||

| > 7000 cells/mm3 |

6.0 |

4.0 |

||||||

|

Lymphocyte counts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| < 1700 cells/mm3 |

7.0 |

1.06 (0.64–1.74) |

0.88 |

4.43 |

0.36 (0.14–0.93) |

0.02 |

||

| > 1700 cells/mm3 |

7.4 |

11.0 |

||||||

|

Monocyte counts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| < 600 cells/mm3 |

8.0 |

1.51 (0.90–2.54) |

0.09 |

7.0 |

0.73 (0.28–1.90) |

0/50 |

||

| > 600 cells/mm3 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

||||||

|

Platelets counts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| < 400 × 103cells/mm3 |

5.0 |

1.12 (0.47–2.66) |

0.78 |

6.0 |

0.44 (0.13–1.53) |

0.17 |

||

| > 400 × 103cells/mm3 |

7.0 |

12.0 |

||||||

|

NLR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| < 4 |

8.0 |

1.67 (1.00–2.80) |

0.05 |

7.0 |

1.68 (0.69–4.07) |

0.23 |

||

| > 4 |

7.0 |

6.0 |

||||||

|

Pro-inflammatory factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 0 |

9.0 |

0.39 (0.20–0.74) | 0.002 | 7.0 |

1.14 (0.48–2.70) | 0.75 | ||

| At least 1 | 7.0 | 7.0 | ||||||

Figure 2. Progression free survival probability according to the baseline inflammatory status (neutrophil count > 7000 cells/mmc, monocyte count > 600/mmc, NLR > 4; see text) in NSCLC patients treated with (A) or without (B) bevacizumab

Figure 3. Overall survival estimation according to the baseline inflammatory status (neutrophil count > 7000 cells/mmc, monocyte count > 600/mmc, NLR > 4; see text) in NSCLC patients treated with (A) or without (B) bevacizumab

Discussion

The present observational retrospective study suggests that the systemic inflammatory status at baseline, indirectly evaluated by measuring white blood cell counts, influences the outcome of patients with advanced NSCLC who receive a treatment containing bevacizumab. In particular, we found that a specific profile based on the concomitant presence of a low neutrophil and monocyte count and a low NLR was strongly associated with longer PFS and OS in patients treated with bevacizumab but not in control patients.

Currently, no clinical or biological factors predictive of resistance to anti-VEGF treatment have been identified and patients are therefore exposed to unnecessary bevacizumab-related adverse effects of an expensive treatment. Gridelli et al. reviewed, in a recent study,15 the various retrospective and prospective analyses conducted on the E4599 and AVAIL trials in order to investigate possible clinical and laboratory predictive factors, underlining that, to date, no clinical or biological markers are reliable candidate for validation and translation in clinical practice. More recently Mok et al., in an exploratory analysis to investigate possible correlation between different biomarker associated with angiogenesis (such as FGF, E-selectin, PIGF, VEGF and VEGF receptors) and RR, failed to find any statistically significant association.16

However, none of these analyses included evaluation of pre-treatment leukocyte subpopulations.

On the other hand, different preclinical models suggest that tumor infiltration by bone marrow-derived inflammatory cells is involved in resistance to antiangiogenic therapy.17 These cells, attracted in the tumor tissue by different stimuli such as hypoxia and/or necrosis, may in turn lead to the development of both VEGF dependent or independent neo-angiogenesis; the latter is not affected by bevacizumab.18

Neutrophils are recruited at the site of inflammation or tumor from the peripheral blood and different immune-histochemistry studies have shown increased neutrophil number in human tumors compared with healthy tissues.19-21 Indeed several tumor transplant models as well as mouse models of tumor development demonstrated that neutrophils are able to promote angiogenesis by releasing different proangiogenic factors such as VEGF, IL-8 and Bv8 or protease such as MMP-9 and to trigger the angiogenic-switch, an essential step for tumor progression.14,22-25 Furthermore, in a recent xenograft study, Shojaei et al. reported increased levels of granulocyte colony stimulating factors (G-CSF) and Bv8 in mice bearing tumors refractory to anti-VEGF treatment thus confirming the essential role of polymorphonucleated cells in VEGF-independent angiogenesis.26

Monocytes are attracted in tumor tissue by different chemokines, such as CCL-2 or CCL-5, produced by cancer cells, fibroblasts or immune cells. Once have reached the tumor site, these cells quickly differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). TAMs could, under certain conditions, switch to a so-called tumor promoting M2-like macrophage polarization, express Tie-2 marker and induce angiogenesis through secretion of different pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF, IL-8, FGF and MMP-9.27,28

NLR represents a marker of systemic inflammation found to be associated with prognosis in different malignancies. Cedrès et al. found a direct association between a high NLR value and poor prognosis in NSCLC patients. Furthermore, they discovered that patients whose NLR normalize during chemotherapy showed improved survival.29 These results are in line with our findings in colorectal cancer (CRC) where we observed an improved survival in patients who experienced a reduction in NLR along the treatment, compared with those who maintained high NLR values.30 Additionally, Keizman et al. reported on the association between a low NLR value and longer PFS and OS in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with the anti-VEGF receptor sunitinib.31 These results are similar to those we found in CRC patients receiving bevacizumab in front-line therapy, where a low baseline NLR value was associated with the longest PFS, mirroring the results of the present study and underscoring the relevance of systemic inflammatory status as marker of resistance to bevacizumab-treatment.32 Of interest, Yao et al. found a prognostic role for pretreatment NLR in NSCLC patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.33 However, this result was not confirmed in our calibration group, probably because of the small sample of patients included.

NLR may also represent an indicator of the balance between neutrophils and lymphocytes, reflecting patients’ immune-status. Host’s immune response to cancer cells is in fact lymphocyte-dependent and different studies reported association between low or high lymphocyte count and survival.34,35 Interestingly, we found in the control group an advantage in term of PFS for patients who presented a high baseline lymphocyte count; however due to the low size of the group no definitive conclusion could be drawn. Moreover, previous results by our group suggested that basal tumor infiltration by both TCCR7 and Treg lymphocyte is predictive of favorable outcome in metastatic CRC patients and that chemo-immunotherapy may modulate patients’ own immune-response36-39. We believe that these findings underline the central role of the interplay between inflammation, angiogenesis and immune system in conditioning cancer patients’ survival and response to treatment supporting the potential role of chemo-immunotherapy in NSCLC.40,41

Our study presents some limitations such as the low number of enrolled patients especially in the control/calibration group, the lack of a validation data set in an independent patient cohort contributing to the preliminary character of this report. Furthermore, other inflammatory index such as reactive C protein (RCP) or erythrosedimentation velocity (ESV) as well as plasma inflammatory cytokines are not routinely measured on NSCLC patients and we could evaluate their impact in the selected outcomes in prospective studies only. Despite these weakness, we believe that the number of neutrophils and monocytes in the peripheral blood as well as NLR may reflect the pro-angiogenic/pro-inflammatory status in tumor tissue, thus leading us to potential identification of patients carriers of tumors that constitutively express different pro-angiogenic pathways, potentially independent from VEGF. These patients, most likely, will not gain any benefit from the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy consistent with our study results indicating lack of bevacizumab benefit in patients with elevated systemic inflammatory markers. We conclude that our study provide a proof of principle that baseline inflammatory status might play an important role in the selection of NSCLC patients candidate to bevacizumab. Further studies are needed to validate our model in larger prospective series and to shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying the strong association between inflammation and angiogenesis.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Seventy-three consecutive patients with advanced (IIIB/IV stage) NSCLC who underwent first line treatment with a platinum-based doublet plus bevacizumab in five Italian Medical Oncology Units (Siena, Catanzaro, Naples, Avellino and Frattamaggiore), between 2008 and 2011, were retrospectively reviewed. We evaluated patients who participated in clinical trials (phase II/III trials).42-44 Thirty-nine advanced NSCLC patients from the same medical centers, treated with chemotherapy alone, were included in our analysis as a control arm. Data were extracted from patient medical records. Data collected for our analysis included: age, gender, pathological confirmed diagnosis of NSCLC, performance status, pre-treatment laboratory findings (in particular neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte and platelet counts), treatment outcomes in terms of response rate (RR), progression free survival (PFS) and OS. In the experimental arm, bevacizumab was administered according to the protocol of the different clinical trials (dose range 5–15 mg/kg every three weeks). In both groups chemotherapy was administered for 4–6 cycles every three weeks or until progression or death or in the presence of unacceptable toxicities. The response was assessed according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. The study was performed according to bioethic standards of participating Institutions and patients had provided consent to data management at trial enrollment.

Statistical analysis

All patients were evaluated for PFS and OS. PFS was defined as time from enrollment to progression disease or death, while OS was defined as time from enrollment to death. Both PFS and OS were considered primary endpoints. All potential prognostic factors were transformed into categorical variables. Patients were grouped as male vs. female, squamous cell carcinoma vs. adenocarcinoma, > 7000 vs. < 7000 cells/mm3 neutrophils count (upper limit of normal), > 1700 vs. < 1700 cells/mm3 lymphocytes count (lower limit of normal), > 600 vs. < 600 cells/mm3 monocytes count (upper limit of normal), > 400 × 103 vs. < 400 × 103 cells/mm3 platelets count (upper limit of normal), < 4 vs. > 4 NLR (measured as the ratio between neutrophil and lymphocyte counts at baseline) (mean of the group). Survival curves and medians were estimated with the Kaplan Meier method and the association between each variable and survival was assessed by Log-Rank test in univariate analysis. Variables with a p value lower than 0.10 were used to construct a predictive model. The Cox proportional hazard model was used subsequently in the multivariate analysis to assess the contribution of each potential prognostic factor to survival. The most significant variables were entered in the model through a step-wise method. The analysis was performed through SPSS version 17 statistical package.

Acknowledgments

There was no founding source from an external sponsor for this research. Dr Botta awarded the FONICAP 2012 prize in memory of “Giovanni Garotti” for this research during the FONICAP meeting 2012 in Verona.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CI

confidence intervals

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- DCR

disease control rate

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- HR

hazard ratio

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NLR

neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- RR

response rate

- RECIST

response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Submitted

02/10/2013

Revised

03/09/2013

Accepted

03/23/2013

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cbt/article/24425

References

- 1.Peters S, Adjei AA, Gridelli C, Reck M, Kerr K, Felip E, ESMO Guidelines Working Group Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii56–64. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NSCLC Meta-Analyses Collaborative Group Chemotherapy in addition to supportive care improves survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 16 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4617–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delbaldo C, Michiels S, Syz N, Soria JC, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP. Benefits of adding a drug to a single-agent or a 2-agent chemotherapy regimen in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:470–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Chevalier T, Scagliotti G, Natale R, Danson S, Rosell R, Stahel R, et al. Efficacy of gemcitabine plus platinum chemotherapy compared with other platinum containing regimens in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of survival outcomes. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajeswaran A, Trojan A, Burnand B, Giannelli M. Efficacy and side effects of cisplatin- and carboplatin-based doublet chemotherapeutic regimens versus non-platinum-based doublet chemotherapeutic regimens as first line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Lung Cancer. 2008;59:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Correale P, Cusi MG, Tagliaferri P. Immunomodulatory properties of anticancer monoclonal antibodies: is the ‘magic bullet’ still a reliable paradigm? Immunotherapy. 2011;3:1–4. doi: 10.2217/imt.10.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, Ramlau R, Gorbounova V, Hirsh V, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1227–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, Ramlau R, Gorbounova V, Hirsh V, et al. BO17704 Study Group Overall survival with cisplatin-gemcitabine and bevacizumab or placebo as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised phase III trial (AVAiL) Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1804–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albini A, Tosetti F, Benelli R, Noonan DM. Tumor inflammatory angiogenesis and its chemoprevention. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10637–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat Med. 2011;17:1359–70. doi: 10.1038/nm.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitale G, Dicitore A, Gentilini D, Cavagnini F. Immunomodulatory effects of VEGF: Clinical implications of VEGF-targeted therapy in human cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:694–8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.9.11691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrara N. Role of myeloid cells in vascular endothelial growth factor-independent tumor angiogenesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:219–24. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283386660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gridelli C, Rossi A. Unanswered questions: monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2010;24:1216–23. [Williston Park] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mok T, Gorbunova V, Juhasz E, Szima B, Burdaeva O, Yu CJ, et al. 9003 ORAL Biomarker Analysis in BO21015, a Phase II Randomised Study of First-line Bevacizumab (BEV) Combined With Carboplatin-gemcitabine (CG) or Carboplatin-paclitaxel (CP) in Patients (pts) With Advanced or Recurrent Non-squamous Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) European journal of cancer. 2011;47 doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)72315-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azam F, Mehta S, Harris AL. Mechanisms of resistance to antiangiogenesis therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1323–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jubb AM, Harris AL. Biomarkers to predict the clinical efficacy of bevacizumab in cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1172–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen BS, Timshel S, Kjeldsen L, Sehested M, Pyke C, Borregaard N, et al. 92 kDa type IV collagenase (MMP-9) is expressed in neutrophils and macrophages but not in malignant epithelial cells in human colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:57–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960103)65:1<57::AID-IJC10>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mentzel T, Brown LF, Dvorak HF, Kuhnen C, Stiller KJ, Katenkamp D, et al. The association between tumour progression and vascularity in myxofibrosarcoma and myxoid/round cell liposarcoma. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s004280000327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Kaya G, Sauter G, McKee T, Donze O, Schwaller J, et al. The source of APRIL up-regulation in human solid tumor lesions. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:697–704. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaider H, Oka M, Bogenrieder T, Nesbit M, Satyamoorthy K, Berking C, et al. Differential response of primary and metastatic melanomas to neutrophils attracted by IL-8. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:335–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shamamian P, Schwartz JD, Pocock BJ, Monea S, Whiting D, Marcus SG, et al. Activation of progelatinase A (MMP-2) by neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3: a role for inflammatory cells in tumor invasion and angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, Fingleton B, Green-Jarvis B, Shyr Y, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nozawa H, Chiu C, Hanahan D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12493–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601807103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shojaei F, Wu X, Qu X, Kowanetz M, Yu L, Tan M, et al. G-CSF-initiated myeloid cell mobilization and angiogenesis mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6742–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902280106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coffelt SB, Tal AO, Scholz A, De Palma M, Patel S, Urbich C, et al. Angiopoietin-2 regulates gene expression in TIE2-expressing monocytes and augments their inherent proangiogenic functions. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5270–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coffelt SB, Chen YY, Muthana M, Welford AF, Tal AO, Scholz A, et al. Angiopoietin 2 stimulates TIE2-expressing monocytes to suppress T cell activation and to promote regulatory T cell expansion. J Immunol. 2011;186:4183–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cedrés S, Torrejon D, Martínez A, Martinez P, Navarro A, Zamora E, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as an indicator of poor prognosis in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14:864–9. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0872-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Botta C, Mazzanti R, Guglielmo A, Cusi M, Vincenzi B, Mantovani G, et al. 1439 POSTER Treatment-related Changes in Systemic Inflammatory Status, Measured by Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio, is Predictive of Outcome in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:S181. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70932-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keizman D, Ish-Shalom M, Huang P, Eisenberger MA, Pili R, Hammers H, et al. The association of pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with response rate, progression free survival and overall survival of patients treated with sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Botta C, Mazzanti R, Cusi M, Vincenzi B, Mantovani G, Licchetta A, et al. 1418 POSTER Baseline Inflammatory Status Defined by Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Cell Count Ratio (NLR) Predicts Progression Free Survival (PFS) in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients (mCRC) Undergoing Bevacizumab Based Biochemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:S174–5. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70911-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao Y, Yuan D, Liu H, Gu X, Song Y. Pretreatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is associated with response to therapy and prognosis of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:471–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1347-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lissoni P, Brivio F, Fumagalli L, Messina G, Ghezzi V, Frontini L, et al. Efficacy of cancer chemotherapy in relation to the pretreatment number of lymphocytes in patients with metastatic solid tumors. Int J Biol Markers. 2004;19:135–40. doi: 10.1177/172460080401900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Correale P, Tagliaferri P, Fioravanti A, Del Vecchio MT, Remondo C, Montagnani F, et al. Immunity feedback and clinical outcome in colon cancer patients undergoing chemoimmunotherapy with gemcitabine + FOLFOX followed by subcutaneous granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and aldesleukin (GOLFIG-1 Trial) Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4192–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Botta C, Bestoso E, Apollinari S, Cusi MG, Pastina P, Abbruzzese A, et al. Immune-modulating effects of the newest cetuximab-based chemoimmunotherapy regimen in advanced colorectal cancer patients. J Immunother. 2012;35:440–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31825943aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Correale P, Rotundo MS, Del Vecchio MT, Remondo C, Migali C, Ginanneschi C, et al. Regulatory (FoxP3+) T-cell tumor infiltration is a favorable prognostic factor in advanced colon cancer patients undergoing chemo or chemoimmunotherapy. J Immunother. 2010;33:435–41. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181d32f01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Correale P, Rotundo MS, Botta C, Del Vecchio MT, Tassone P, Tagliaferri P. Tumor infiltration by chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7)(+) T-lymphocytes is a favorable prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:531–2. doi: 10.4161/onci.19404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Correale P, Rotundo MS, Botta C, Del Vecchio MT, Ginanneschi C, Licchetta A, et al. Tumor infiltration by T lymphocytes expressing chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) is predictive of favorable outcome in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:850–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vitale G, Abbruzzese A, Tonini G, Santini D. Chemo-immunotherapy: a new option for non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:503–4. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.6.7770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Correale P, Tindara Miano S, Remondo C, Migali C, Saveria Rotundo M, Macrì P, et al. Second-line treatment of non small cell lung cancer by biweekly gemcitabine and docetaxel +/- granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor and low dose aldesleukine. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:497–502. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.6.7593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Correale P, Botta C, Basile A, Pagliuchi M, Licchetta A, Martellucci I, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and dose/dense chemotherapy with cisplatin and metronomic daily oral etoposide in advanced non-small-cell-lung cancer patients. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:112–8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.2.15722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Correale P, Remondo C, Carbone SF, Ricci V, Migali C, Martellucci I, et al. Dose/dense metronomic chemotherapy with fractioned cisplatin and oral daily etoposide enhances the anti-angiogenic effects of bevacizumab and has strong antitumor activity in advanced non-small-cell-lung cancer patients. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:685–93. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.9.11441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crinò L, Dansin E, Garrido P, Griesinger F, Laskin J, Pavlakis N, et al. Safety and efficacy of first-line bevacizumab-based therapy in advanced non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SAiL, MO19390): a phase 4 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:733–40. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]