Abstract

Approximately 2–4 per cent of small bowel obstructions (SBO) are caused by bezoars. In addition, presentation with features of acute surgical abdomen is extremely rare, accounting for only 1% of the patients. A bezoar is a concretion of indigestible material found in the gastrointestinal tract, which usually forms in the stomach and passes into the small bowel, where it can cause SBO. We present the case of a 63-year-old male who presented with SBO following ingestion of boiled olive leaves as herbal treatment for diabetes mellitus.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 2–4 per cent of small bowel obstructions (SBOs) are caused by bezoars. In addition, presentation with features of acute surgical abdomen is extremely rare, accounting for only 1% of the patients [1]. A bezoar is a concretion of indigestible material found in the gastrointestinal tract, which usually forms in the stomach and passes into the small bowel, where it can cause SBO. It can be classified into one of four major types: trichobezoar, pharmacobezoar, lactobezoar and phytobezoar. Trichobezoars are composed of hair and are most commonly associated with patients who have a psychiatric disorder [2]. Pharmacobezoars are composed of undigested medication. Lactobezoars are more commonly seen in neonates and are comprised of milk curd. Phytobezoars are composed of undigested fiber from vegetables or fruits and are the most common form of bezoar encountered as a postoperative complication after gastric bypass [3].

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old Syrian male presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of generalized colicky abdominal pain associated with repeated vomiting and absolute constipation. There was no associated history of alteration of bowel habit, rectal bleeding, fever or dysuria.

His past medical history was significant for a laparotomy in 1979 due to a peptic ulcer-related complication, but he was unaware of the details. He was also recently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus for which he was using herbal treatment consisting of boiled olive tree leaves (Olea europaea).

On physical examination, the patient looked unwell but was hemodynamically stable and apyrexial. His abdomen was distended. There was a midline laparotomy scar with a reducible incisional hernia in the epigastric area. He had mild lower abdominal tenderness with no muscle guarding and his bowel sounds were exaggerated. Rectal examination revealed no abnormalities and there was a small amount of stool in the rectum.

The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Routine blood investigation and abdominal X-rays were obtained. Apart from leukocytosis, they were unremarkable.

A contrast-enhanced CT scan was arranged and it showed features of SBO with collapse of the terminal ileum. There was evidence of a previous gastrojejunostomy with suspected foreign bodies in the stomach and proximal ileum. (Figs 1 and 2) .

Figure 1:

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan in coronal view showing evidence of gastrojejunostomy and visible foreign body in the stomach and features of small bowel obstruction.

Figure 2:

Sagittal CT scan view showing foreign bodies in the stomach and the ileum with transition point in the small bowel.

At laparotomy, a previous gastrojejunostomy with dense adhesions in the upper abdomen was found. An obstructing hard foreign body was palpable in the ileum with dilatation of the proximal small bowel loops. A larger similar foreign body was mobile and palpable within the stomach. (Fig. 3) Both foreign bodies were removed through an enterotomy and gastrotomy, respectively, and the bowel was decompressed. After limited adhesiolysis, the abdomen was closed en mass repairing the midline hernia defect.

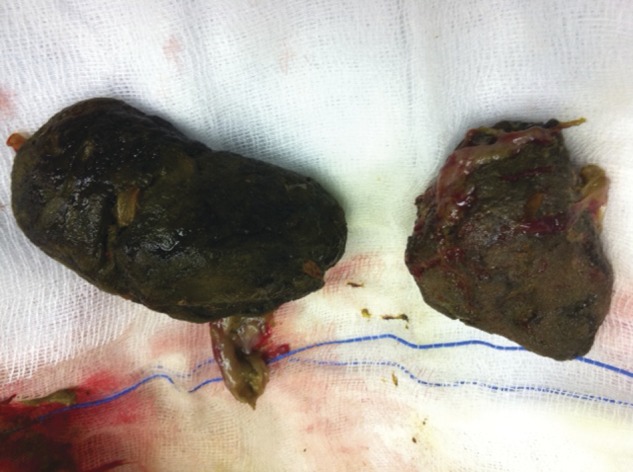

Figure 3:

Retrieved phytobezoars.

Postoperative recovery was unremarkable except for a short duration of ileus, after which the patient made a steady recovery. He was referred to the diabetology department and dietician during admission and was discharged with outpatient clinic follow-up.

A follow-up upper GI endoscopy was done and it showed evidence of a hiatus hernia with gastrooesophageal reflux disease. The patient was well controlled on Proton pump inhibitors and remained largely symptom free.

DISCUSSION

There are numerous predisposing factors that can contribute to the formation of phytobezoars. The most common risk factor is previous gastric surgery. The incidence of bezoar formation after gastric surgery ranges from 5 to 12 per cent [2]. The main pathogenesis of bezoar formation is believed to be the result of gastric dysmotility and decreased gastric secretions, which is very common after any gastric surgery [3, 4].

Diospyrobezoars, formed after persimmon ingestion, are a distinct type of phytobezoars characterized by their hard consistency. Coca-Cola ingestion combined with endoscopic techniques has been used effectively to treat gastric phytobezoars and avoid surgery [5].

Phytobezoar should be considered in patients with previous gastric outlet surgery who present with bowel obstruction and features of acute surgical abdomen. The presence of a well-defined intraluminal mass with a mottled gas pattern on emergency CT scan is suggestive of an intestinal phytobezoar [1].

Postoperative nutritional counseling is important in regard to preventing recurrence of bezoar formation. Guidelines include proper chewing of food, plenty of liquids with meals and avoidance of a high-fiber diet[6].

REFERENCES

- 1.Salemis N, Panagiotopoulos N, Sdoukos N, Niakas E. Acute surgical abdomen due to phytobezoar-induced ileal obstruction. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:e21–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kement M, Ozlem N, Colak E, Kesmer S, Gezen C, Vural S. Synergistic effect of multiple predisposing risk factors on the development of bezoars. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:960–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i9.960. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i9.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarhan M, Shyamali B, Fakulujo A, Ahmed L. Jejunal bezoar causing obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. JLSL. 2010;14:592–5. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12924466008682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yakan S, Sirinocak A, Telciler KE, Tekeli MT, Deneçli AG. A rare cause of acute abdomen: small bowel obstruction due to phytobezoar. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16:459–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladas S, Kamberoglou D, Karamanolis G, Vlachogiannakos J, Zouboulis-Vafiadis I. Systematic review: Coca-Cola can effectively dissolve gastric phytobezoars as a first-line treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:169–73. doi: 10.1111/apt.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsi S, Rivera C, Vargas J, Silberstein M. Laparoscopic-assisted extirpation of a phytobezoar causing small bowel obstruction after Roux-en-Y laparoscopic gastric bypass. Am Surg. 2013;79:E93–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]