Abstract

Rapid and highly sensitive detection of the carbohydrate components of glycoconjugates is critical for advancing glycobiology. Fluorescence (or Forster) resonance energy transfer (FRET) is commonly used in detection of DNA, in protein structural biology, and in protease assays, but is less frequently applied to glycan analysis due to difficulties in inserting two fluorescent tags into small glycan structures. We report an ultrasensitive method for the detection and quantification of a chondroitin sulfate disaccharide based on FRET, involving a CdSe-ZnS core-shell nanocrystal quantum dot (QD)-streptavidin conjugate donor and a Cy5 acceptor. The disaccharide was doubly labeled with biotin and Cy5. QDs then served to concentrate the target disaccharide, enhancing the overall energy transfer efficiency, with unlinked QDs and Cy5-hydrazide producing nearly zero background signal in capillary electrophoresis using laser-induced fluorescence detection with two different band-pass filters. This method is generally applicable to the ultrasensitive analysis of acidic glycans and offers promise for the high-throughput disaccharide analysis of glycosaminoglycans.

Keywords: Fluorescence resonance energy transfer, quantum dots, glycosaminoglycans, ultrasensitive detection, capillary electrophoresis

Introduction

Fluorescence (or Föster) resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a process involving the transfer of energy from donor fluorophore to acceptor fluorophore when the distance between the donor and the acceptor is smaller than a critical radius, known as the Forster radius (R0). This leads to a reduction in the donor's emission and excited state lifetime and an increase in the acceptor's emission intensity.1 FRET is widely applied in measuring protein conformational changes,2 and in enzyme activity assays.3 But FRET has infrequently been applied to carbohydrate analysis due to the general lack of appropriately spaced, reactive sites on glycans for the introduction of two fluorescent tags. Acidic glycans, such as glycosaminoglycan-derived disaccharides, offer an attractive FRET target as they have both a single reactive hemiacetal reducing end and a single non-reducing end carboxyl group.4

FRET requires fluorescent molecules in close proximity in the range of 0–2 R0. Even at very high concentrations non-interacting donors and acceptors do not undergo FRET. This is considered an advantage of FRET, as excess donor and/or acceptor fluorophores are often used to promote non-bonded interactions of donor and acceptor. Since this large excess of unbound fluorophore should not add to FRET, a purification step, typically required in most fluorescence experiments is unnecessary. While FRET is primarily detected using separation-free spectroscopic and microscopic imaging techniques,5–10 in practice, these detection methods can lead to misleading or even meaningless results.11 The major factor causing inaccuracy in calculating FRET efficiency is crosstalk between the two fluorophores. Not only can the acceptor be excited with the light selected to excite the donor, but some of the detected fluorescence can also come from the excited donor. Quantum dots (QDs) have emerged as particularly effective FRET donors due to their narrow emission spectra. While QDs can decrease excitation crosstalk, they cannot eliminate spectral crosstalk in the detected signal. One approach for completely eliminating crosstalk is to combine a separation method with FRET analysis.

Capillary electrophoresis (CE) is a powerful high-resolution method capable of separating QDs and their conjugates.12,13 In the commonly used capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE), a bare fused silica capillary can separate QDs with different charge-to-size ratios under optimized conditions. While capillary gel electrophoresis,14 has also applied to improve resolution of QDs and QD-bioconjugate mixtures, a decrease in detection sensitivity often results. Several groups13,15,16 have reported the CE-based separation of QDs and their bioconjugates. FRET has been detected between water-soluble CdTe QD donor and 632-nm emitting CdSe/ZnS QD acceptor covalently conjugated with antibodies using CE-LIF.17 FRET has also been applied between QDs donor and Cy5 acceptor bound to a polypeptide for measuring protease activity using CE as separation tool for bound and unbound QDs.1,3,5 However, the separation of QDs and QD-disaccharide conjugate is particularly challenging because the relatively small size of a disaccharide and the challenges associated with the introduction of donor and acceptor fluorophores. In the current study we have prepared a disaccharide FRET complex and optimized its separation by CE and its detection by laser-induced fluorescence (LIF).

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

All the chemicals and materials used in the experiment were of analytical grade unless otherwise indicated. QD-605 streptavidin conjugate (QDSA) and incubation buffer were purchased from Invitrogen Inc., USA. The conjugates were received as 1 μM solution in a pH 8.3 buffer composed of 50 mM borate, 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.05% sodium azide (preservative). QDs were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) upon arrival (see supplementary Figure S1). Cy5-hydrazide was purchased from Lumiprobe Co., USA. Chondroitin sulfate (CS)-A, from bovine trachea, was purchased from Celsus Laboratories, Cincinnati, OH. Chondroitin lyases ABC and ACII were purchased from Associates of Cape Cod, Inc., East Falmouth, MA. Biotin hydrazide, sodium cyanoborohydride (NaBH3CN), menthol (MeOH), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), glacial acetic acid (HAc), N-methylmorpholine (NMM), 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT), and fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I (FITC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

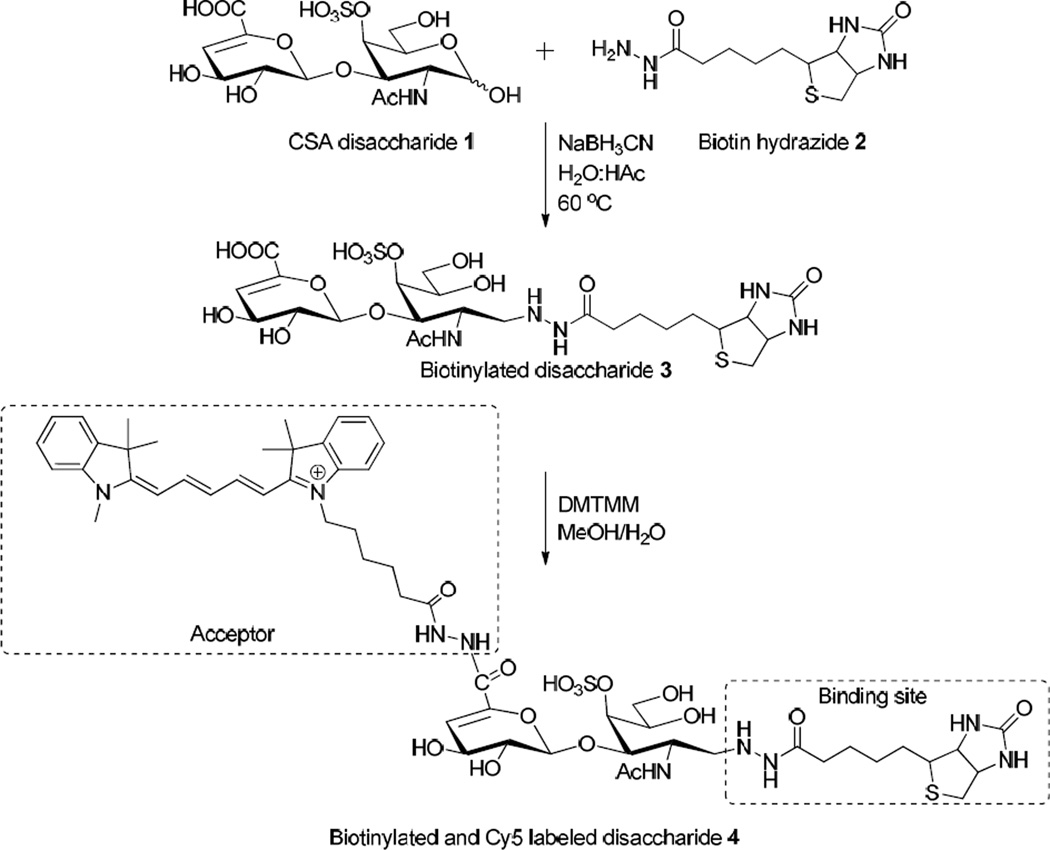

Biotinylation of chondroitin sulfate disaccharide

CS disaccharide 1 (Figure 1) was prepared from CS-A by exhaustive chondroitin lyase treatment and purified as previously described.4 This monosulfated chondroitin disaccharide 1 was selected as a model glycosaminoglycan disaccharide for double labeling, structural characterization, and for high-sensitivity FRET detection. Biotin hydrazide 2 was used for CS disaccharide 1 biotinylation. The CS disaccharide 1 (5.0 mg, 12.4 mmol) was dissolved in a solution of H2O (1.7 mL) and AcOH (0.3 mL). NaBH3CN (1.2 mg, 18.6 mmol) and biotin hydrazide 2 (4.8 mg, 18.6 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture. The reaction was stirred at 60 °C for 3 days. On each day, additional portions of NaBH3CN (1.2 mg, 18.6 mmol) and biotin hydrazide (4.8 mg, 18.6 mmol) were added. The reaction mixture was loaded onto a BioGel P2 column (2.5 × 65 cm) and eluted with H2O. Fractions were collected and those containing the product as determined by TLC (n-BuOH/AcOH/H2O= 2/2/1) were combined and freeze-dried to afford the biotinylated disaccharide 3 as a white powder.

Figure 1.

Synthesis pathway is shown for the Cy5-disaccharide-biotin FRET acceptor.

Coupling of Cy5 to biotinylated disaccharide

DMTMM was prepared by adding NMM (2.02 g, 20 mmol) to a solution of CDMT (3.86 g, 22 mmol) in THF (60 ml) at room temperature. A white solid appeared within several minutes. After stirring for 30 min at room temperature, the solid was collected by suction and washed with THF and dried to give DMTMM (100%). Although the DMTMM was of high purity, it was recrystallized from methanol and diethylether before using. Biotinylated disaccharide 3 (1 mg) was dissolved in methanol–water (9:1, 5 ml) together with the Cy5-hydrazide (1.2 eq.) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. Recrystallized DMTMM (1.5 eq.) was then added and the reaction stirred at room temperature until complete (5–14 h). The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue co-evaporated with absolute ethanol affording the biotinylated, Cy5-labeled disaccharide 4.

Complexation of QD-605 streptavidin QDSA with biotinylated Cy5-labeled disaccharide 4

Complexation of QD-605 streptavidin (QDSA) with biotinylated Cy5-labeled disaccharide 4 was carried out in QD incubation buffer provided by Invitrogen Inc. Before conjugation, QDSA was centrifuged at 5, 000 × g for 3 min, any precipitate was discarded before reaction. 32, 20, 16, 12, 8, 4, 2, 1 pmol 4, and 1 μl of QDSA (1 μM) were added to incubation buffer, respectively. The final concentration of QDSA is 10 nM. The mixtures were left in dark for 5 h to complete the conjugation. Samples were diluted with incubation buffer to desired concentration for CE-LIF analyses 4-QDSA complex.

Instrumentation

CE analyses were carried out on an Agilent G1600 High Performance CE system coupled with a ZETALIF (Picometrics, France) detector (λex = 488 nm). Resolution and analysis were performed on an uncoated fused-silica capillary column (25, 50 or 75 μm ID, indicated in each experiment) at 25 °C, using 50 mM carbonate buffer, pH 9.0 (unless otherwise indicated), at different voltages, as shown in figures, normal polarity. New capillary was treated with MeOH, 1 M HCl, 1 M NaOH, 0.1 M NaOH, water and operating buffer, until the baseline got constant. Between each run, the capillary was flushed with 0.1 M NaOH (3 min), HPLC grade water (3 min), and operating buffer (5 min). The operating buffer was filtrated through a 0.2 μm membrane filter. All solutions were degassed. Samples were introduced using the pressure mode (50 mbar × 5 s) at the anode. The emission filters of 488 nm-bandpass and 650 nm-bandpass were also purchased from ZETALIF (Picometrics, France). Each time after switch the filter, an optical performance optimization was performed with flushing the capillary with 10−6 M FITC.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed with a Philips CM12 (Eindhoven, Amsterdam, Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV in bright-field mode. Dispersed quantum dots on 400 mesh TEM grids were obtained by adding one drop of diluted aqueous quantum dots solution onto carbon coated TEM copper grid and allowing solvent to evaporate, then further drying in vacuum oven for 2 h.

RESULTS

Design and synthesis of the QD/Cy5-disaccharide-bintin as FRET acceptor

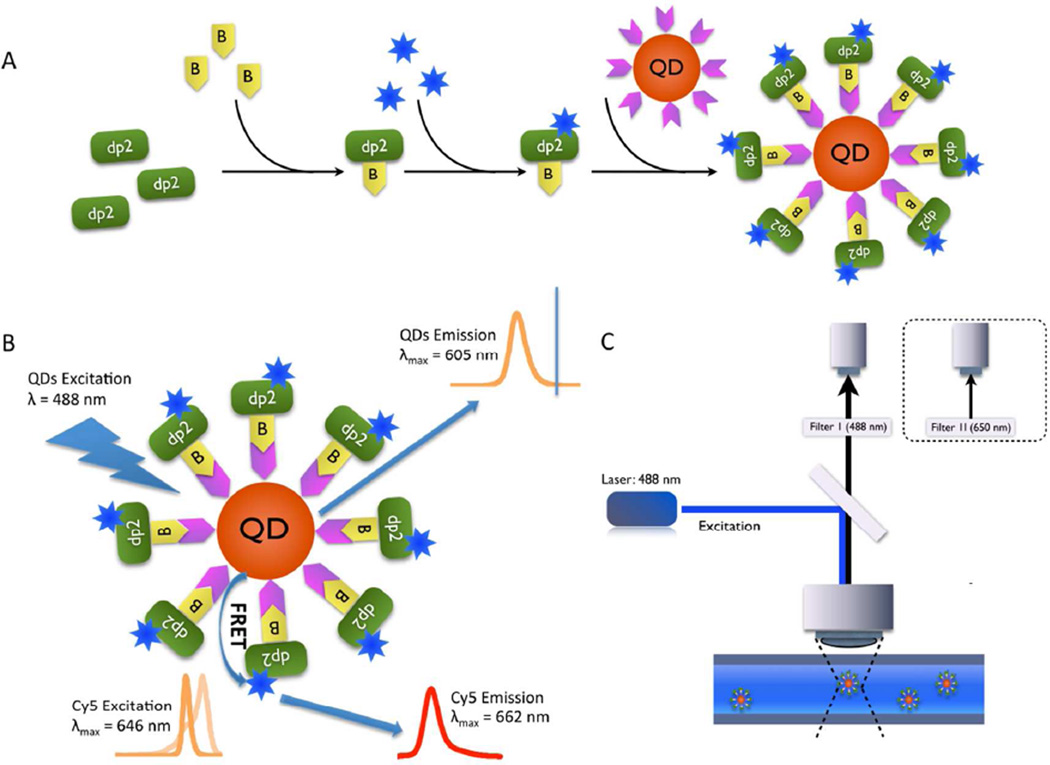

The FRET complex and its assembly is shown in Figure 2A. A commercially available CdSe-ZnS core-shell nanocrystal streptavidin conjugate (QDSA) with a 15–20 nm diameter (Figure S1) was chosen as FRET donor and Cy5-hydrazide was selected as FRET acceptor (Figure 1). The Cy5-hydrazide FRET acceptor was coupled to a chondroitin sulfate-derived disaccharide that had been biotinylated in a high yield (80–90%) by reductive amination reaction (Figure 1 and Figure 2A).18

Figure 2.

Scheme of FRET system construction in this study. (A) Conjugation scheme of FRET system. Disaccharide (degree of polymerization (dp)2,  ) is biotinylated (B,

) is biotinylated (B,  ) then coupled to FRET acceptor, Cy5-hydrazide (

) then coupled to FRET acceptor, Cy5-hydrazide ( star). Incubation at room temperature and in the dark of Cy5-dp2-biotin complex 4 to QD streptavidin conjugate (QDSA,

star). Incubation at room temperature and in the dark of Cy5-dp2-biotin complex 4 to QD streptavidin conjugate (QDSA,  and

and  ) forms the FRET complex 4-QDSA. (B) The FRET donor, QD, is excited with a laser at 488 nm, because Cy5 dye, located on the same disaccharide, is close FRET occurs and Cy5 is excited by emission from the QD, and the emission of Cy5 is then detected. (C) CE-LIF instrumental set-up for FRET detection. A 488 nm- (Filter I, donor + acceptor channel) and 650 nm- (Filter II, acceptor channel) band-pass filter was used for FRET detection.

) forms the FRET complex 4-QDSA. (B) The FRET donor, QD, is excited with a laser at 488 nm, because Cy5 dye, located on the same disaccharide, is close FRET occurs and Cy5 is excited by emission from the QD, and the emission of Cy5 is then detected. (C) CE-LIF instrumental set-up for FRET detection. A 488 nm- (Filter I, donor + acceptor channel) and 650 nm- (Filter II, acceptor channel) band-pass filter was used for FRET detection.

The selection of QDSA and Cy5 as FRET pair (Figure 2B) allows the steady-state fluorescence detection by a CE-LIF system equipped with a 488 nm Argon Ion excitation laser and two different band-pass filters (488 nm and 650 nm cut-off) (Figure 2C). The use of two filters with different cut-off wavelengths can distinguish the fluorescence coming from donor and acceptor. Using the 488 nm cut-off filter, fluorescence from QDSA at 605 nm and fluorescence from Cy5 (resulting from energy transferred by the QD) at 662 nm are both detected. Using the 650 nm cut-off filter, the fluorescence from QDSA was nearly completely filtered out, as a result, only the fluorescence emission from Cy5 at 662 nm (coming from energy transferred by the QD) is detected. The negative controls, unassembled components, Cy5 and QDSA, were also tested, and produced almost no background fluorescence.

As a FRET model for disaccharide analysis, a chondroitin sulfate-derived disaccharide 1 was biotinylated by reductive animation (Figure 1), so that it could be bound to the QDSA through a strong non-covalent streptavidin-biotin interaction (Figure 2A). The biotinylated disaccharide 2 was next covalently conjugated to Cy5-hydrazide using a carbodiimide reaction. Because a double bound at the non-reducing end of this disaccharide is produced in the enzymatic digestion of chondroitin sulfate, conventional carbodiimide coupling did not effectively promote the reaction between the unsaturated carboxyl group on biotinylated disaccharide 3, and Cy5 hydrazide. Instead, the more reactive 4-(4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-4-methylmorpholinium chloride (DMTMM)19 was used to facilitate this coupling reaction, affording the biotinylated and Cy5 labeled disaccharide 4. The last step is to assemble QDSA to biotinylated and Cy5-labeled disaccharide 4 to form a FRET pair 4-QDSA (Figure 2A). When the 488 nm laser light (Figure 2C) excites the QD, resulting in QD emission, excitation of Cy5 and emission of Cy5 FRET, allowing detection of the disaccharide analyte (Figure 2B).

CZE Separation of QDs and QD-disaccharide complex

Conditions for the CE separation of QDSA from its 4-QDSA FRET complex was next examined. CZE of QDSA in a bare fused silica 75 µm internal diameter (I.D.) capillary using 50 mM sodium borate, sodium carbonate, Tris-hydrochloride and sodium phosphate buffers at pH 9.0 showed that the sodium carbonate buffer gave narrowest peak width (Figure S2). Furthermore, 18 injections of QDs in sodium carbonate buffer showed excellent repeatability and a small RSD of migration time (2.1%), and peak areas (2.8%).

The separation of QDSA from 4-QDSA complex by CZE was examined on a 75 µm I.D. capillary at pH 8–11. Disaccharide 4 was incubated with QDSA in the dark for 5 h and CZE was performed on a mixture of QDSA and 4-QDSA complex (Figure S3). Complete separation of QDSA and 4-QDSA complex was unsuccessful. Interestingly, the elution order of QDSA and 4-QDSA complex reversed when the pH of running buffer reached 10. This is attributed to the pH-dependence of the negatively charged residues in the streptavidin coating on QDSA. Peak broadening at pH 10.0 to 11.0, suggested that neither QDSA nor 4-QDSA complex were stable in buffer higher than pH 9.0, thus, pH 9.0 was selected for subsequent experiments.

Next, the effect of voltage 8 to 16 kV on the separation of QDSA and 4-QDSA complex was examined (Figure S4). As separation voltage decreased, migration time of both analytes increased and peak broadening was observed and resolution did not significantly increase, thus, 16 kV affording the fastest migration time was selected for subsequent experiments.

The utilization of polymeric additives as sieving medium can improve the CE separation of analytes, particularly biomolecules.16,20 CE analysis of a mixture of QDSA and 4-QDSA complex was carried out using various polyethylene glycol (PEG) (20 kDa) concentrations (0–4%) as sieving medium (Figure S5). At 2% PEG solution gave an optimal separation of QDQDSA and 4-QDSA complex. We concluded that the enhanced resolution justified the slight decrease in fluorescence intensity observed and, thus, 2% PEG was included in subsequent experiments.

Finally, an ultra-thin capillary (25 µm I.D., 50 cm effective length), was used for the CE separation of QDSA and 4-QDSA complex in 50 µm sodium bicarbonate (pH 9) containing 2% PEG at 16 kV to afford optimal separation (Figure S6).

FRET detection of 4-QDSA complex on CE-LIF

Reaction mixtures with donor-acceptor ratio of 1:20 with a final QDSA concentration of 10 nM were incubated for 1 to 6 h and then analyzed by CE-LIF to determine optimal time for the formation of 4-QDSA complex. Mixtures of QDSA and Cy5-hydrazide of the same molar ratio were used as a negative control. In this study, the percentage of 4-QDSA FRET complex in the mixture was approximately calculated by

| (2) |

where A4-QDSA complex is the peak area of the 4-QDSA FRET complex, and AQDSA is the peak area of QDSA. The relative value of quantum yield was β = 2.5 (β equals to 1 only when the quantum yield of two fluorophores are not significantly different).

The electrophoresis peaks of QDSA and 4-QDSA FRET complex were observed in donor + acceptor channel (488 nm filter), whereas in acceptor channel (650 nm filter) only fluorescence from 4-QDSA FRET complex was observed (Figure S7A & S7C). The percentage and fluorescence intensity of 4-QDSA FRET complex increased as reaction time increased (Figure S7B & S7D). After 2 h, the percentage of 4-QDSA FRET complex reached 50% and after 4 h it increased to 92%, and reached ~ 100% at 5 h. Therefore, 5 h was chosen as the complex formation time in subsequent experiments. In the control experiments (Figure S7C) with unlinked QDSA and Cy5-hydrazide (1:20), fluorescence signal were not detected in the acceptor channel, indicating that no crosstalk was occurring between donor and acceptor. The FRET efficiency was calculated at ~ 85%.

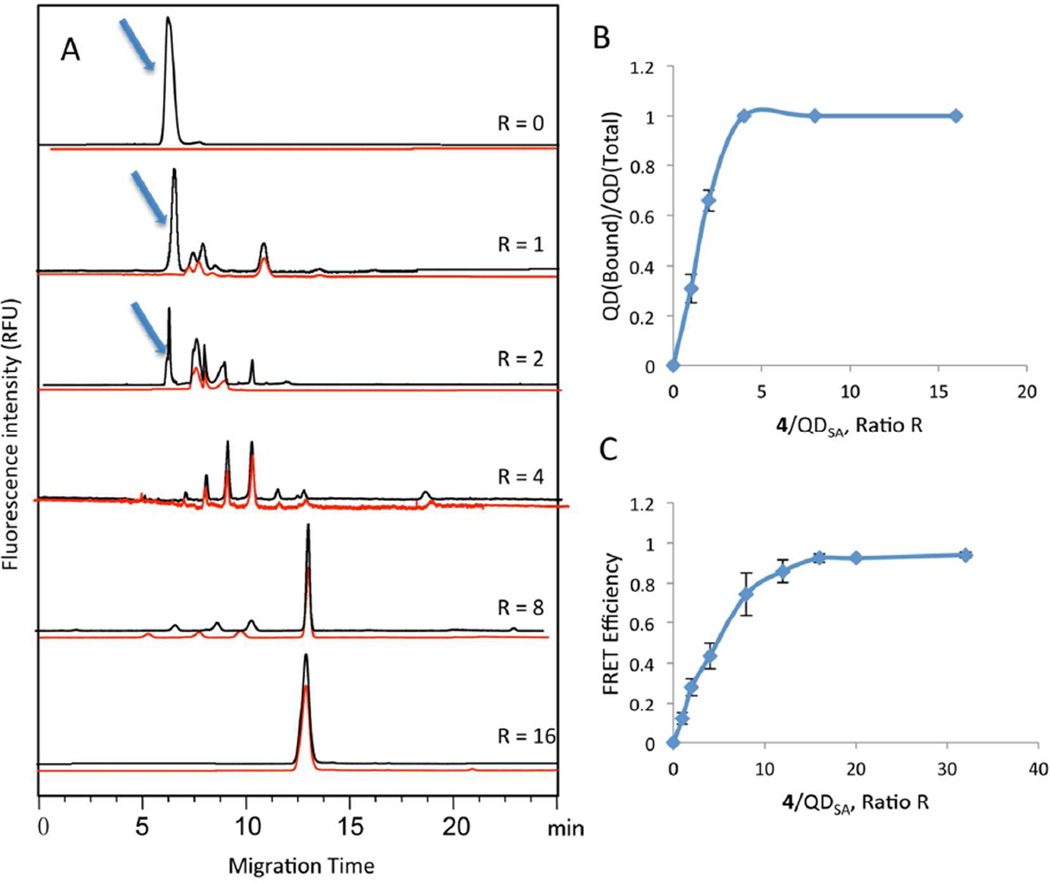

The concentrations of both QDSA and 4-QDSA FRET complex needs to be optimized to perform quantitative FRET. The optimum ratio (R) of biotinylated Cy5 disaccharide to QD-650 streptavidin conjugate was examined (Figure 3A). Because QDSA is well resolved from the 4-QDSA FRET complex, an accurate calculation of FRET efficiency and binding percentage could be obtained. While saturation of QD binding occurred at R = 4 (Figure 3B), multiple peaks of FRET complex were observed until R = 16, when FRET efficiency reached 91% and remained unchanged even at higher R-values (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

FRET between Cy5-labeled biotinylated disaccharide 4 and QD-605 streptavidin conjugate QDSA at different ratios. (A) Electrophorograms of complexes of 4 and QDSA at different ratios (4/QDSA, R = 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16), monitored by CE-LIF from donor + acceptor channel (black) and acceptor channel ( ). (B) The percentage of bound QDs increase with increasing R, and reaches 100% an R of 4/1. (C) The FRET efficiency increases as R increases, and reaches a saturated state at an R of 16/1. The final QDs concentration in reaction mixture was 10 nM and the amount of 4 present was 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 pmol, respectively.

). (B) The percentage of bound QDs increase with increasing R, and reaches 100% an R of 4/1. (C) The FRET efficiency increases as R increases, and reaches a saturated state at an R of 16/1. The final QDs concentration in reaction mixture was 10 nM and the amount of 4 present was 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 pmol, respectively.

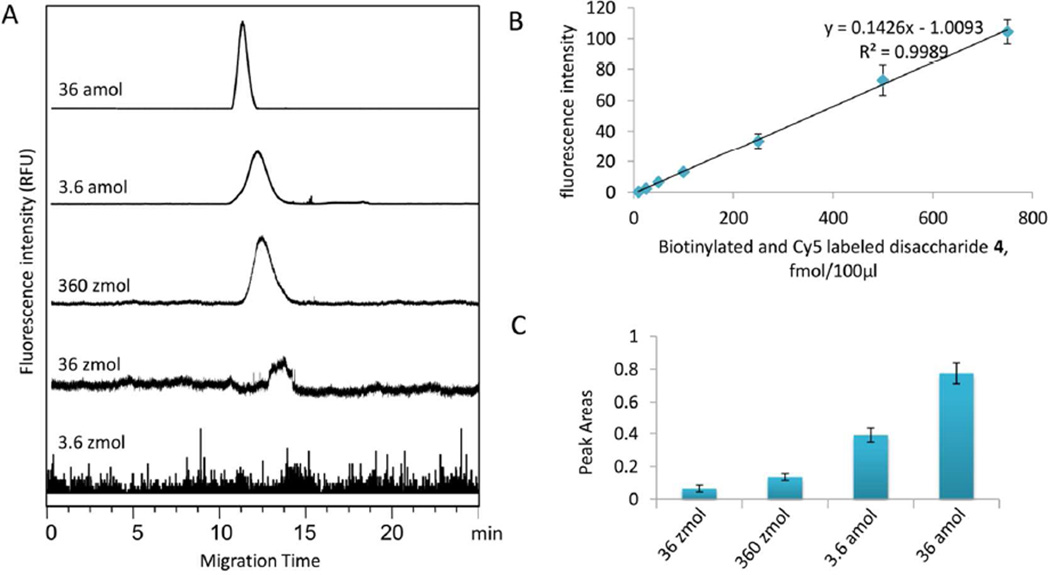

Determination of limit of detection

The quantitative properties of the method were tested by injecting a series of different 4-QDSA FRET complexes. A standard curve was plotted from 10 fmol/100 μl to 750 fmol/100 μl, a ratio of 4:QDSA was fixed at 20:1, and the peak area from the 4-QDSA FRET complex from acceptor channel was recorded and integrated (Figure 4). A limit of detection (LOD) of 36 zmol disaccharide (21, 600 molecules of 4) was obtained. Ten injections were performed to test CE repeatability at 1 pmol/100 μl, a RSD of 1.2% in peak areas and 0.9% in migration time of the 4-QDSA FRET complex in the acceptor channel indicates the method has excellent repeatability. Moreover, the complex was stable in the dark at room temperatures for at least 5 days and a very low variance of FRET signal in acceptor channel was observed at the low concentrations tested (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

FRET-based disaccharide assay. (A) Electropherograms of injection of 36 amol to 3.6 zmol of 4-QDSA complex. (B) Linear equation of fluorescence intensity of FRET complex from acceptor channel plotting against concentration of 4-QDSA complex, from 10 fmol to 750 fmol per 100 μl solution. (C) Variance of FRET intensity from acceptor channel at 36 zmol to 36 amol with three parallel injections.

DISCUSSION

FRET requires a donor having a high quantum yield; spectral overlap of the emission spectrum of donor and absorbance spectrum of acceptor; close proximity (R0) between donor and acceptor; and an effective detection system. Unlike organic dyes, QDs offer some advantages when serving as FRET donors. Because QDs have higher quantum yield than conventional dyes, a QDs/organic dye hybrid FRET system usually produces higher sensitivity than organic-only FRET systems. QDs also have a narrow emission spectrum, which helps to decrease the level of background fluorescence and avoid spectral crosstalk and direct acceptor excitation.21 Furthermore, QDs have longer fluorescent lifetimes, can undergo many excitation cycles, and have size-dependent excitation wavelengths, making QDs excellent candidates as FRET donors.

In this paper we designed a FRET system with a QD and an organic dye, Cy5, when coupled to CE-LIF detection, serves as a probe for ultrasensitive quantification. The QD-Cy5 FRET pair, selected for minimum spectral overlap between donor emission and acceptor absorbance, were limited through multiple streptavidin proteins on the QD surface to enrich multiple Cy5 acceptors on a single QDs, thus, maximizing the overall energy-transfer efficiency and sensitivity.22 The QD-605 streptavidin conjugate (QDSA) has 4 to 10 biotin binding sites per QD on the surface.23 Therefore, energy transfer efficiency between QDSA and Cy5 was markedly enhanced.

A biotinylated disaccharide 3 serves as an extremely high affinity (10−14 M) bridge between the Cy5 acceptor and the QDSA donor. This interaction is resistant to extremes of heat, pH and proteolysis, making it a good candidate for CE-based separation. The Forster radius of this 4-QDSA FRET pair, can be calculated according by

| (1) |

where κp2 is 2/3 for randomly oriented dipoles,21 the quantum yield for QDs is usually about 0.5, the refractive index nD is 1.4 for biomolecules in aqueous solution.24 For Cy5, εA(λ) is expressed as an extinction coefficient, εA(λmax) = εA(647) = 250,000 cm−1M−1. So R0 for FRET pair QD-605/Cy5, is about 6 nm.

Because QDSA has a broad excitation wavelength range, 488 nm was chosen as the excitation wavelength, minimizing the direct excitation of Cy5 to nearly zero by the laser source. In addition, the narrow emission spectrum of QDSA resulted in negligible crosstalk between the QDSA and Cy5 fluorophores. QDs and cyanine dye are among the most efficient FRET pairs used over the past decade.15,25,26 However, most of these FRET systems have generally applied to structural study of larger biomolecules (i.e. proteins and DNA) and not small glycans. Moreover, FRET was mostly detected by imaging and microscopic techniques, which is relatively difficult to apply for quantitative analysis. The highly efficient separation power of CE for donor-acceptor complexes and the unlinked fluorophores, as well as the ability to reflect possible changes in fluorescence intensity due to the conformation changes of donor-acceptor ratio, contributes to the lower analysis uncertainty (variance) and higher FRET efficiency observed in the current study, resulting more sensitive FRET analysis. A simple two-filter CE-LIF system for quantitative determination of disaccharide (Figure 2C) was used that could be easily extended to other FRET system based on QDs. CE separation of donor-acceptor complexes from free donor eliminates the interference of non-FRET signal impurity. Thus, this CE-based technique possesses unique advantages of improved FRET efficiency, high sensitivity, and low sample volume requirements.

High resolution CE was demonstrated to be effective in separating very small amounts of donor from FRET complex, thus, solving the problem of signal impurity associated with most conventional FRET measurements. The CE-based separation of QDs and QD complexes typically shows very broad peaks. This is because earlier methods of QD synthesis had resulted in relatively broad size-distribution of QDs. Improved QD synthesis has afforded commercially available QDs and derivatized QDs that are much more homogeneous size, although some size dispersity is still present. Significant optimization of the CE separation was first required, including the selection of mobile phase, capillary type and voltage conditions. Sodium borate buffer, the most commonly used buffer for CZE separation of QDs, afforded relatively broader peaks than those observed for sodium carbonate buffer. As the buffer pH was increased, the negative charge of the QDSA nanoparticles increased, whereas the net negative charge on disaccharides in the 4-QDSA complex changed very little. Thus, a pH change from 9.0 to 11.0 both broadened peaks and increased elution time without improving resolution, making pH 9.0 optimal pH value. PEG additive afforded a sieving effect, associated with the pore size of the sieving media, improving peak resolution. However, higher PEG concentration resulted in peak broadening and poorer separations. At these higher PEG concentrations pores become too small for these large analytes to enter, decreasing resolution. The 2% PEG sieving medium concentration, selected to provide optimal performance, is in agreement with previous reports.20

In conclusion, the combination of the high extinction coefficient of the Cy5 dye and high QD quantum yield at a high ratio of dye acceptor per QD donor allows one to achieve efficient FRET with an efficiency of 92%. This sensitive method can detect and quantify disaccharides at concentrations of 36 zeptamole, over 1000-fold sensitive than fluorescent labeling of disaccharide analysis by CE-LIF.27 Moreover, the double labeling of other glycosaminoglycan-derived disaccharides and sialic acid-containing glycans has been recently reported,4 making it possible to extend this detection platform to other acidic carbohydrates, including ones present in proteoglycans, glycolipids and glycoproteins.24 Furthermore, because the capacity of multiple binding of targets per QDs, this method can be potentially applied to oligosaccharide or polysaccharide analysis, which normally has a low FRET due to the long chain and large donor-acceptor distance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the US National Institutes of Health in the form of grants GM38060, HL62244 and HL096972 to R.J.L. and a fellowship from the Turkish government to E.U. and a fellowship from the Chinese government to G.L.

References

- 1.Jamieson T, Bakhshi R, Petrova D, Pocock R, Imani M, Seifalian AM. Biomaterials. 2009;28:4717–4732. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heyduk T. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:292–296. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li JJ, Bugg TD. Chem. Commun. 2004:182–183. doi: 10.1039/b313316h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwon S-J, Lee K-B, Solakyildirim K, Masuko S, Ly M, Zhang F, Dordick JS, Linhardt RJ. Angew. Chemie. 2012;51:11800–11804. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truong K, Ikura M. Curr. Opin. Struc. Biol. 2001;11:573–578. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majumdar ZK, Hickerson R, Noller HF, Clegg RM. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;351:1123–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piston DW, Kremers GJ. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Mills JD, Periasamy A. Differentiation. 2003;71:528–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2003.07109007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Munster EB, Gadella TWJ. J. Microsc.-Oxford. 2004;213:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2004.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jovin TM, Lidke DS, Jares-Erijman EA. Nato Sec. Sci. B. Phys. 2005;3:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Puhl HL, Koushik SV, Vogel SS, Ikeda SR. Biophys. J. 2006;91:L39–L41. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang YH, Zhang HS, Ma M, Guo XF, Wang H. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009;255:4747–4753. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vicente G, Colon LA. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:1988–1994. doi: 10.1021/ac702062u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song XT, Li L, Chan HF, Fang NH, Ren JC. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:1341–1346. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang JH, Xia J. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;709:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo CK, Paau MC, Xiao D, Choi MM. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:2330–2339. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li YQ, Wang JH, Zhang HL, Yang J, Guan LY, Chen H, Luo QM, Zhao YD. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010;25:1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ait-Mohand K, Lopin-Bon C, Jacquinet JC. Carbohydr. Res. 2012;353:33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falchi A, Giacomelli G, Porcheddu A, Taddei M. Synlett. 2000:275–277. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li YQ, Wang HQ, Wang JH, Guan LY, Liu BF, Zhao YD, Chen H. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009;647:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang CY, Yeh HC, Kuroki MT, Wang TH. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:826–831. doi: 10.1038/nmat1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. 3rd ed. Springer, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qdot® Streptavidin Conjugates (Invitrogen Inc.) User handbook. [Data Last Accessed April 11, 2013]; http://probes.invitrogen.com/media/pis/mp19000.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clapp AR, Medintz IL, Mauro JM, Fisher BR, Bawendi MG, Mattoussi H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:301–310. doi: 10.1021/ja037088b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Hu XF, Sun YM, Zhang XL, Jin WR. Electrochem. Commun. 2011;13:1174–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tani T, Oda M, Sakai H, Araki D, Itoh Y, Ohtaki A, Yohda M. J. Lumin. 2011;131:519–522. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang Y, Yang B, Zhao X, Linhardt RJ. Anal. Biochem. 2012;427:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.