Abstract

The DF3/MUC1 gene is aberrantly overexpressed in human breast and other carcinomas. Previous studies have demonstrated that the DF3/MUC1 promoter/enhancer confers selective expression of diverse transgenes in MUC1-positive breast cancer cells. In this study, we show that an adenoviral vector (Ad.DF3-E1) in which the DF3/MUC1 promoter drives expression of E1A selectively replicates in MUC1-positive breast cancer cells. We also show that Ad.DF3-E1 infection of human breast tumor xenografts in nude mice is associated with inhibition of tumor growth. In contrast to a replication-incompetent adenoviral vector that infects along the injection track, Ad.DF3-E1 infection was detectable throughout the tumor xenografts. To generate an Ad.DF3-E1 vector with the capacity for incorporating therapeutic products, we inserted the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter upstream of the TNF cDNA. Infection with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF was associated with selective replication and production of TNF in cells that express MUC1. Moreover, treatment of MUC1-positive, but not MUC1-negative, xenografts with a single injection of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF was effective in inducing stable tumor regression. These findings demonstrate that the DF3/MUC1 promoter confers competence for selective replication of Ad.DF3-E1 in MUC1-positive breast tumor cells, and that the antitumor activity of this vector is potentiated by integration of the TNF cDNA.

Introduction

Recombinant adenoviruses have been used as highly efficient vectors for in vitro and in vivo gene transfer. Adenovirus-mediated gene transduction has been achieved in a broad spectrum of eukaryotic cells, and is independent of cell replication (1, 2). In addition, the E1 gene–deleted, replication-defective adenoviruses can accommodate large DNA inserts (1, 2). However, limitations of this vector system for cancer therapy have included the nonselective delivery of therapeutic genes to both normal cells and tumor cells. Moreover, the replication-defective adenoviruses are limited by their inability to infect and then spread to neighboring tumor cells. Strategies to circumvent these limitations have involved the use of promoters or enhancers that are specific to or selective for tumor tissue in order to direct replication of the adenovirus in the desired target cells (3). In this context, the minimal promoter/enhancer from the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) gene has been used to drive E1A expression and thereby create an adenovirus, designated CN706, that selectively replicates in PSA-positive cells (4). A similar strategy using the albumin promoter has been used to develop a herpes simplex virus that selectively replicates in hepatoma cells (5).

The DF3/MUC1 antigen is a high-molecular-weight glycoprotein that is aberrantly overexpressed in human breast and other carcinomas (6–8). The MUC1 gene contains seven exons and has been mapped to chromosome 1q21-24 (9, 10). It spans 4–7 kb’s, depending on the number of conserved 60-bp tandem repeats. Overexpression of the MUC1 gene in human breast cancer cells is regulated at the transcriptional level (11, 12). Cloning and characterization of the 5′ flanking region of the MUC1 gene has shown that expression of the gene is regulated mainly by sequences between positions –598 bp and –485 bp upstream from the transcription start site (13). The MUC1 promoter/enhancer region has been shown in the context of retroviral vectors to direct expression of prodrug-activating enzymes and to confer selective killing of MUC1-positive human carcinoma cells (14). In other studies with replication-defective adenoviruses, the MUC1 promoter has been used to selectively express β-galactosidase (β-gal) or herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) in MUC1-positive breast cancer cells (15).

In this study, we have constructed an adenovirus in which E1A sequences are expressed under control of the MUC1 promoter. The results demonstrate that the virus replicates selectively in MUC1-positive cells in vitro. We also demonstrate that the virus is effective in expressing the TNF transgene and in treating MUC1-positive breast cancer xenografts in nude mice.

Methods

Cells and cell culture.

The following cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia, USA): MCF-7, ZR-75-1, BT-20, and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell lines; the Hs578Bst myoepithelial cell line derived from normal breast tissue adjacent to an infiltrating ductal carcinoma; the PA-1 human ovarian cancer cell line; and the human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cell line. MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, Hs578Bst, and HEK 293 cells were cultured in DMEM. ZR-75-1 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES. The BT-20 and PA-1 cell lines were grown in Eagle’s MEM. All media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Structure of the DF3 promoter replication-competent adenovirus.

A 480-bp portion of the E1 gene was generated from pKSCMVE1 (16) using the primers A2s(475)XS (5′-GGACTAGTAAGCTTCTCCAGCCCGTGAGTTCCTCAAGAGG-3′) and A2a(921)NS (5′-TCCCCCGGGCTAGCATCGATCACCTCCGGCACAA-3′). The 480-bp fragment was digested with SpeI and SmaI restriction enzymes and then ligated into pAdClxB (plasmid 1) (16). The DF3 promoter region was amplified from pDF3 using primer DF3.5′ (5′-TCTAGACTAGTGTGGACCCTAGGGTTCATCGGAG-3′) and DF3.3′ (5′-AACTCGAGGATTCAGGCAGGCGCTGGCT-3′). The resulting 780-bp fragment was ligated into plasmid 1 using SpeI and XhoI restriction sites to generate plasmid 2. The remaining E1A sequence (∼5 kb) was digested from the pKSCMVE1 region and cloned into plasmid 2 using complementary ClaI restriction enzyme sites (pDF3-E1/CMV). The cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter sequence was then deleted to generate pDF3-E1, which contains the DF3 promoter to drive the E1A gene. A marker plasmid was constructed by inserting green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA into pDF3-E1/CMV at the BamHI site (pDF3-E1/CMV-GFP). Construction of pDF3-E1/CMV-TNF was performed by substituting GFP with the TNF cDNA sequence (17).

Replication-competent adenovirus under control of the DF3 promoter was prepared by standard homologous recombination techniques using the adenoviral packaging plasmid pJM17 (kindly provided by F. Graham, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) in HEK 293 cells. Three micrograms of each shuttle plasmid was mixed with 6 μg pJM17 and precipitated with CaCl2. This was used to transfect HEK 293 cells. Recombinant adenovirus was isolated from a single plaque and expanded in HEK 293 cells. DNA was purified and analyzed by PCR.

Virus was prepared by infecting eighty 15-cm plates of HEK 293 cells and harvesting the detached cells after 48 hours. The virus remained associated with the cells. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The cells were resuspended in 10 mL of cold PBS (free of Ca2+ and Mg2+), and were lysed with three cycles of freeze and thaw. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,500 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was placed on a gradient prepared with equal parts of CsCl in PBS (1.45 g/mL and 1.20 g/mL), and then centrifuged for 2 hours at 15,000 g at 12°C. The virus band was removed, rebanded in a preformed CsCl gradient by ultracentrifugation for 18 hours, and dialyzed into cold 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 10% glycerol. Titers of purified adenovirus were determined by spectrophotometry and by plaque assays.

The shuttle plasmids pCMV-LacZ and pCMV-TNF were used to generate the Ad.CMV–β-gal and Ad.CMV-TNF recombinant adenoviruses in which expression of LacZ or TNF is driven by the CMV promoter. Ad.DF3–β-gal was prepared as described (15).

Indirect immunofluorescence analysis of MUC1 antigen.

Cells (2 × 105) were washed extensively with cold PBS, incubated with mAb DF3 (1 μg/mL) at 4°C for 1 hour, and washed with cold PBS. Cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) at 4°C for 1 hour, washed with cold PBS, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Intensity of fluorescence was determined for 10,000 cells.

Western blot analysis of Ad2 E1A and Ad5 E1B expression.

Three days after viral infection, cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 10 mM NaF, 10 ng/mL aprotinin, 10 ng/mL leupeptin, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM sodium vanadate), incubated for 30 minutes on ice, and centrifuged at 1,500 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and heated at 100°C for 5 minutes. Protein was analyzed by immunoblotting with mAb Ad2 E1A or Ad5 E1B (1 μg/mL; Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). Reactivity was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Life Sciences Inc., Arlington Heights, Illinois, USA).

In vitro viral replication assay.

Monolayer cell cultures in 24-well dishes (5 × 104 cells/well) were infected with Ad.DF3-E1, Ad.DF3-E1/CMV, Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF, or wild-type Ad5 at an moi of 1.0 plaque-forming units (pfu) per well. Virus inocula were removed after 2 hours. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and incubated at 37°C for varying periods of time. Lysates were prepared with three cycles of freeze and thaw. Serial dilutions of the lysates were titered on HEK 293 cells.

Cytopathic effect assays.

Cells were prepared 24 hours before infection with adenoviruses at the indicated moi. Photomicrographs were taken on days 3, 5, and 7 after infection.

ELISA.

On days 1, 3, 5, and 7 after viral infection, supernatants were assayed for TNF levels using the Human Tumor Necrosis Factor ELISA kit from Sigma Chemical Co.

In vivo gene transfer to human breast cancer xenografts.

Female athymic nude mice (Taconic Farms, Germantown, New York, USA) aged 5–6 weeks were implanted subcutaneously with a pellet of estradiol-17β (1.7 mg, 60-day release; Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, Florida, USA) 1 day before tumor inoculation. Tumors were established by subcutaneous injection of 107 MCF-7 cells or MDA-MB-231 cells in 0.2 mL of 50% Matrigel (Becton Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) and 50% PBS into the flanks of mice. Tumors were allowed to grow to approximately 6–7 mm in diameter. For intratumor injection, 30 μL of virus suspension in PBS was injected using a 25-gauge needle. Tumors were measured at the indicated times after injection in their longest dimension and at 90 degrees to that measurement. Tumor volumes were calculated using this formula: (length × width2)/2. Tumor volumes were normalized to 100% on day 0 (V/V0). Results are expressed as the fractional tumor volume (mean ± SD). Statistical significance was assessed with the Student’s t test.

Histopathological analysis.

At 4–5 weeks after tumor implantation, up to 2 × 108 pfu of purified adenovirus were injected into MCF-7 tumor xenografts using a Hamilton syringe with a 26-gauge needle. The needle was coated with fine charcoal particles to mark the needle track. Tumors were sectioned for analysis of reporter gene expression.

Results

Selective replication of an adenovirus in MUC1-positive cells in vitro.

To construct an adenovirus that replicates selectively in MUC1-positive cells, we placed the DF3/MUC1 promoter upstream of the E1 region. Ad.DF3-E1 was constructed by inserting the expression cassette at the deleted E1 region of the replication-defective Ad5 virus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of Ad.DF3-E1. ITR, inverted terminal repeat; m.u., map unit.

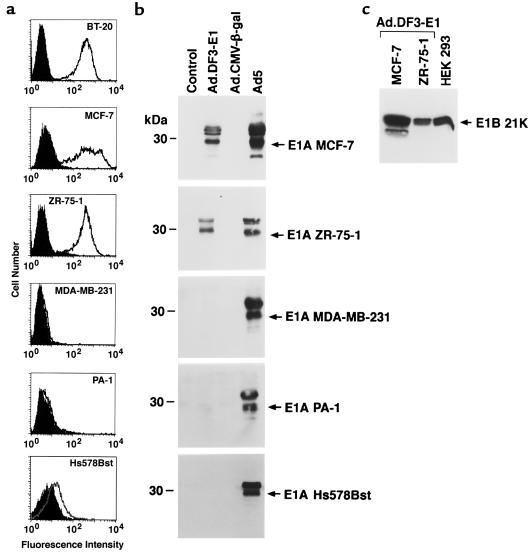

Human cell lines were used to assess the selectivity of Ad.DF3-E1 viral replication. As determined by flow cytometry with an anti-MUC1 Ab, the MCF-7, ZR-75-1, and BT-20 breast cancer cells expressed MUC1 (Figure 2a). The MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and PA-1 ovarian cancer cells, by contrast, exhibited little if any MUC1 expression and were used as controls (Figure 2a). Moreover, MUC1 expression was detectable, but decreased, in breast Hs578Bst epithelial cells compared with that in the breast cancer cell lines (Figure 2a). The cells were infected with Ad.DF3-E1 at an moi of 10 for a period of 2 hours, and then washed and resuspended in medium. E1A protein expression was assessed by immunoblot analysis. The results demonstrate expression of E1A in the MUC1-positive MCF-7 and ZR-75-1 cells, but not in the MUC1-negative MDA-MB-231 and PA-1 cells (Figure 2b). There was also little if any detectable E1A expression in Ad.DF3-E1–infected Hs578Bst cells (Figure 2b). As controls, the cells were also infected with a replication-defective Ad5 virus expressing β-gal under control of the CMV promoter (Ad.CMV–β-gal) or with wild-type Ad5. Whereas there was no detectable E1A expression in cells infected with Ad.CMV–β-gal, E1A was expressed by each of the cells infected with wild-type Ad5 (Figure 2b). Expression of the E1B gene was also detectable in MUC1-positive, but not MUC1-negative, cells infected with Ad.DF3-E1 (Figure 2c and data not shown). These findings indicate that infection with Ad.DF3-E1 results in selective expression of E1A in breast cancer cells.

Figure 2.

Selective expression of E1A in MUC1-positive cells infected with Ad.DF3-E1. (a) The indicated cells were incubated with either mAb DF3 (open area) or an isotype-identical control Ab (shaded area) and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. (b) Cells were infected with Ad.DF3-E1, Ad.CMV–β-gal, or wild-type Ad5. Lysates from control (noninfected) and infected cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-E1A Ab. (c) Lysates from Ad.DF3-E1–infected cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-E1B.

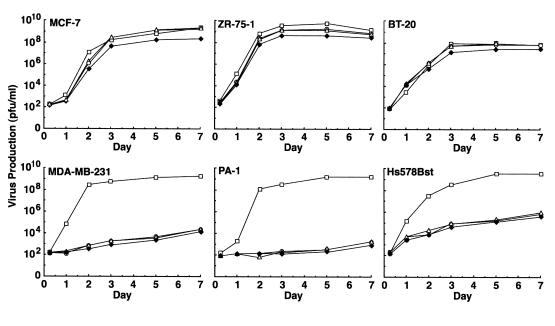

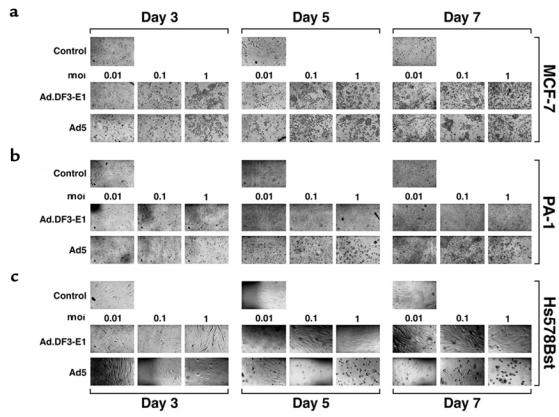

Viral titers were assessed by examining plaque formation to evaluate Ad.DF3-E1 replication in the different cell lines. In MUC1-positive MCF-7 cells, ZR-75-1 cells, and BT-20 cells, Ad.DF3-E1 replicated at levels comparable to that of wild-type Ad5 (Figure 3). By contrast, compared with Ad5, the titer of Ad.DF3-E1 was reduced by 5–6 logs in MUC1-negative MDA-MB-231 and PA-1 cells, and by 4–5 logs in Hs578Bst cells (Figure 3). To determine whether Ad.DF3-E1 induces selective cell lysis, we infected MCF-7 cells, PA-1 cells, and Hs578Bst cells at moi’s of 0.01, 0.1, and 1.0. Plaque formation was assessed on days 3, 5, and 7. Although the MCF-7 cells displayed Ad.DF3-E1–induced lysis (Figure 4a), there were no apparent cytopathic effects of Ad.DF3-E1 on PA-1 (Figure 4b) or Hs578Bst (Figure 4c) cells. These results are in concert with the cell-dependent expression of E1A, and demonstrate selective replication of Ad.DF3-E1 in MUC1-positive breast cancer cells.

Figure 3.

Replication efficiency of Ad.DF3-E1 (open circles), Ad.DF3-E1/CMV (open triangles), Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF (filled diamonds), and wild-type Ad5 (open squares) in human cell lines. Monolayers in 24-well plates were infected at an moi of 1.0 pfu per cell. Virus production was assessed by plaque assays.

Figure 4.

Cytopathic effects associated with Ad.DF3-E1 infection. MCF-7, PA-1, and Hs578Bst cells were infected with either Ad.DF3-E1 or wild-type Ad5 at the indicated moi. Photomicrographs were obtained at the indicated times after infection. ×200.

Treatment of breast tumor xenografts with Ad.DF3-E1.

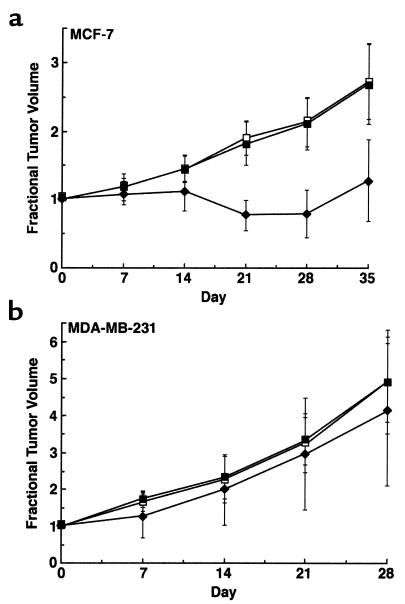

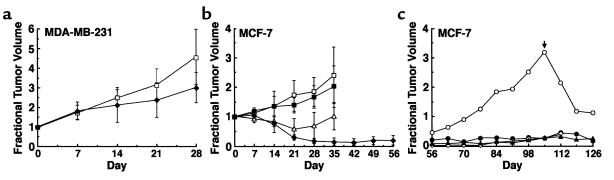

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of Ad.DF3-E1 in vivo, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast tumor xenografts were established in nude mice and then injected once with 2 × 108 pfu of Ad.DF3-E1. As controls, tumors were injected with either PBS or the replication-defective Ad.DF3–β-gal virus. Infection with Ad.DF3-E1 was associated with inhibition of MCF-7 tumor growth (Figure 5a). By 4 weeks after Ad.DF3-E1 injection, the tumors had regressed to being barely palpable (Figure 5a). These findings were in contrast to the progressive growth of tumors injected with PBS or Ad.DF3–β-gal (Figure 5a). By contrast, Ad.DF3-E1 had no apparent effect on growth of MDA-MB-231 tumors (Figure 5b). These results indicate that a single injection of Ad.DF3-E1 results in selective cytolysis and regression of an MUC1-positive tumor.

Figure 5.

Effects of Ad.DF3-E1 on growth of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 tumor xenografts in nude mice. MCF-7 (a) or MDA-MB-231 (b) tumor xenografts were grown subcutaneously to volumes of 150–200 mm3. Groups of mice (n = 5) were treated with 2 × 108 pfu of Ad.DF3-E1 (filled diamonds) or Ad.DF3–β-gal (filled squares) by intratumoral injection on day 0. An equal volume of PBS was injected as a control (open squares). Tumors were measured weekly. The results are expressed as fractional tumor volume (V/V0). MCF-7 tumors infected with Ad.DF3-E1 were significantly smaller than those treated with PBS or Ad.DF3–β-gal at day 21 (P < 0.001), day 28 (P < 0.001), and day 35 (P < 0.01).

Distribution of Ad.DF3-E1 in tumors.

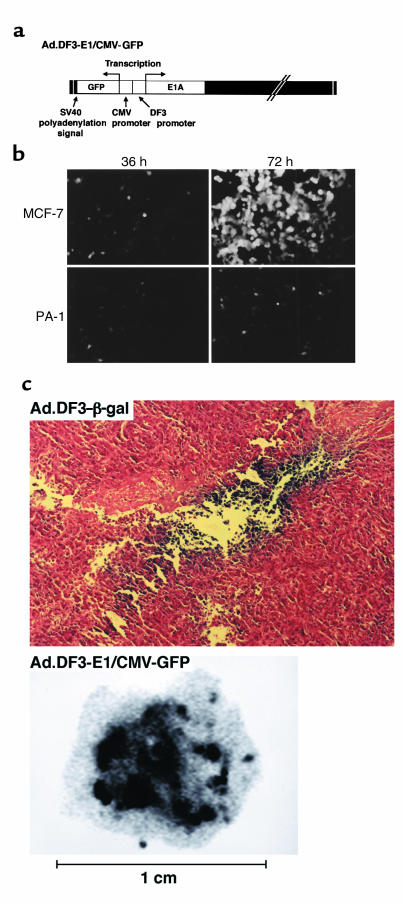

An obstacle to using gene therapy to treat cancer is the difficulty in distributing the vector throughout the tumor mass. The finding that Ad.DF3-E1 induces tumor regression supports the spread of this virus beyond the initial infection site. To assess viral distribution and to generate competent Ad.DF3-E1 viruses that have the capacity to incorporate additional transgenes, the CMV promoter was inserted upstream of the gene expressing GFP (Figure 6a). Infection of MCF-7 cells with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP (moi = 10) was associated with little GFP expression at 36 hours (Figure 6b). However, by 72 hours after infection (a period sufficient for viral replication), there was clearly detectable GFP expression and induction of cytopathic effects (Figure 6b and data not shown). A similar infection of PA-1 cells resulted in significantly less GFP expression at 72 hours, with no evidence of lysis (Figure 6b and data not shown). The Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP virus was also injected into MCF-7 tumor xenografts to assess viral distribution. As a control, the tumor was injected with the replication-defective Ad.DF3–β-gal virus. Staining of the tumor for β-gal expression demonstrated Ad.DF3–β-gal infection only along the needle track (Figure 6c). By contrast, GFP expression was detectable throughout the tumor mass (Figure 6c). These findings demonstrate that the competent Ad.DF3-E1 virus, but not the replication-defective virus, spreads throughout the tumor.

Figure 6.

Characterization and intratumoral distribution of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP. (a) Structure of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP. (b) MCF-7 cells and PA-1 cells were infected with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP at an moi of 10. GFP expression was assessed by photomicrographic examination at 36 hours and 72 hours after infection. (c) MCF-7 tumor xenografts (150 mm3) were injected with 2 × 108 pfu of Ad.DF3–β-gal (upper panel) or Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP (lower panel). At 21 days after injection, the tumors were removed, embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek USAInc., Torrance, California, USA), and frozen on dry ice. They were then cryosectioned with a microtome. Sections were fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde and stained with X-gal (upper panel; ×200). Sections shown in lower panel were visualized by STORM (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, California, USA).

Expression of TNF by Ad.DF3-E1.

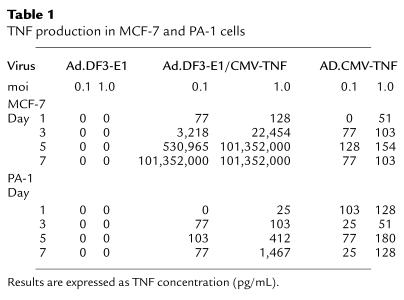

Construction of the MUC1-competent Ad.DF3-E1 virus with the capacity to express additional transgenes allows for the insertion of various genes encoding therapeutic products. TNF was selected as an initial candidate because of its direct antitumor activity (18). Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF virus was constructed by substituting GFP with TNF sequences (Figure 7a). To assess the effects of the CMV promoter on transcription driven by the DF3 promoter, we compared E1A expression in MUC1-positive MCF-7 and ZR-75-1 cells that were infected with either Ad.DF3-E1 or Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF. The results demonstrate that the CMV promoter has little if any effect on transcription driven by the DF3 promoter (Figure 7b). Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF infection of MCF-7 cells, but not PA-1 cells, was also associated with cytopathic effects (data not shown). In addition, growing the Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF virus in MUC1-positive cells resulted in titers that were 4–5 logs higher than those of the virus grown in MUC1-negative cells. These higher titers supported replication that is, like that of Ad.DF3-E1, dependent on MUC1 expression (data not shown). Consistent with these findings, infection of MCF-7 cells with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF was associated with production of TNF that was 106-fold higher than that obtained after infection with Ad.CMV-TNF (Table 1). In addition, TNF production by Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF–infected MCF-7 cells was also 105- to 106-fold higher than that obtained by a similar infection of PA-1 cells (Table 1). These results demonstrate that Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF is selective for MUC1-positive cells and that it expresses the TNF transgene.

Figure 7.

Characterization of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF. (a) Structure of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF. (b) Cells were infected with Ad.DF3-E1 or Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF. Lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-E1A.

Table 1.

TNF production in MCF-7 and PA-1 cells

Treatment of human breast tumor xenografts with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF.

MUC1-positive MCF-7 and MUC1-negative MDA-MB-231 tumors were established in nude mice to assess treatment with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF. Mice bearing tumors of 150–200 mm3 were injected intratumorally with 108 pfu of virus in PBS. Compared with injections of PBS alone, treatment of MDA-MB-231 tumors with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF resulted in growth-inhibiting effects (Figure 8a). Similarly, treatment of MCF-7 cells with the defective Ad.CMV-TNF virus was associated with partial suppression of growth (Figure 8b). These results indicate that expression of TNF in the context of a replication-incompetent virus is insufficient to induce tumor regression. In contrast to these findings, treatment of MCF-7 tumors with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF, but not Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP, was associated with regression to barely palpable tumors (Figure 8b). Four of the five animals were followed for longer periods; one animal exhibited tumor regrowth, and the other three had barely palpable tumors (Figure 8c). Retreatment of the recurrent tumor with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF on day 105 was associated with subsequent regression (Figure 8c). These findings indicate that antitumor activity is potentiated in the setting of a virus that exhibits selective competence for replication and expression of the TNF transgene.

Figure 8.

Antitumor effects of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF. MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 tumor xenografts were grown subcutaneously in nude mice to volumes of 150–200 mm3. (a) Groups of mice (n = 5) bearing MDA-MB-231 tumors were injected intratumorally with PBS (open squares) or 108 pfu of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF (filled diamonds) on day 0. (b) Groups of mice (n = 5) bearing MCF-7 tumors were injected intratumorally with PBS (open squares), 108 pfu of Ad.CMV-TNF (filled squares), 108 pfu of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF (filled diamonds), or 108 pfu of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP (open triangles) on day 0. (c) Mice bearing MCF-7 tumors injected with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF were followed for more than 56 days. One mouse died on day 52 without any tumors. Of the remaining four mice, one exhibited tumor regrowth (open circles). This mouse was reinjected with 108 pfu of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF on day 105 (arrow). The results are expressed as fractional tumor volume (V/V0). Differences among the MDA-MB-231 treatment groups were not significant. MCF-7 tumors infected with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF were significantly smaller at day 35 than were those treated with Ad.CMV-TNF (P < 0.001) or Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Nearly 80% of primary human breast carcinomas express high levels of MUC1 antigen (6). Other studies have shown that human breast tumors express the MUC1 gene at the mRNA and protein levels in approximately 30-fold greater amounts than are found in normal breast tissue and benign lesions (19). These findings and the demonstration that MUC1 expression is regulated at the transcriptional level in breast tumor cells in culture (11) have supported activation of the MUC1 gene in transformed mammary epithelium. Although studies of MUC1 expression have been largely focused on breast tumor cells, other work has demonstrated that MUC1 is overexpressed in diverse carcinomas, including ovarian (8), prostate (20), pancreas (21), and lung cancers (22). On the basis of these findings, and considering the potential for identifying elements in the MUC1 promoter that are activated in carcinomas, sequences responsible for MUC1 transcription were cloned from the 5′ flanking region of the MUC1 gene (13). Subsequent work using retroviral and adenoviral vectors demonstrated that the MUC1 promoter is functional in directing selective and efficient expression of heterologous genes in MUC1-positive cells (14, 15). In vivo experiments using breast tumor implants in nude mice injected with Ad.DF3–β-gal demonstrated that β-gal expression is limited to the MUC1-positive xenografts, predominantly along the needle track (15). Moreover, in a model of intraperitoneal breast cancer metastases, treatment with Ad.DF3–HSV-tk and ganciclovir (GCV) resulted in inhibition of tumor growth (15).

A significant obstacle to cancer gene therapy, even after direct intratumoral administration, is the limited distribution of the vector within the tumor mass. Coadministration of replication-defective virus expressing suicide genes with wild-type virus (23, 24) or with genes essential for replication (25) has been explored to increase transduction efficiency. Direct injection of retroviral producer cells into brain tumors has also been performed to achieve intratumoral vector production (26). Other studies with an E1B gene–deleted adenovirus have demonstrated selective replication in p53-mutant tumor cells and antitumor activity (27–30). Conflicting results, however, have been reported in regard to the relationship between replication of the E1B-deleted virus and p53 status (31–33). Our studies have used yet another strategy to increase transduction efficiency. The results demonstrate that insertion of the MUC1 promoter upstream of the E1A gene confers selective expression of these proteins in MUC1-positive cells. The results also demonstrate that the Ad.DF3-E1 virus induces selective lysis of tumor cells that express MUC1. Of importance, the replication-competent Ad.DF3-E1 virus spread throughout the tumor mass, whereas the replication-defective Ad.DF3–β-gal was restricted to infection of cells along the needle track. These findings indicate that Ad.DF3-E1 and other vectors with the capacity to selectively replicate in tumors have the potential for greater efficacy than that achieved with replication-defective viruses.

Insertion of the PSA promoter into Ad5 to drive expression of E1A has generated a virus known as CN706, which is competent for replication in PSA-positive prostate cancer cells (4). CN706 has been further engineered to include the human glandular kallikrein (hK2) promoter to induce expression of the E1B gene (34). The use of both promoters in the CV764 virus has resulted in further attenuation of growth in nonprostate cancer cells (34). In our current study with Ad.DF3-E1, the MUC1 promoter has been used to drive expression of E1A. Replication of Ad.DF3-E1 in MUC1-positive cells was increased by 5–6 logs over that obtained in MUC1-negative cells. The selectivity of Ad.DF3-E1 replication in MUC1-positive cells is comparable to that of CV764 in prostate cells (34). In vivo studies with the CN706 virus have further demonstrated lysis of PSA-positive tumor xenografts (4). Similar findings of tumor regression were obtained in our current studies with Ad.DF3-E1 and MUC1-positive MCF-7 xenografts. By contrast, injection of MCF-7 tumors with a replication-defective virus had little if any effect on tumor growth. Moreover, injection of MUC1-negative MDA-MB-231 tumors with Ad.DF3-E1 had little effect on tumor growth. These findings support selective replication of Ad.DF3-E1 in MUC1-positive tumors in vivo and, thereby, lysis of the tumor cells.

E1B-deleted adenoviruses, which are replication competent in cancer cells (27, 28), have been engineered to express the HSV-tk gene and to thereby sensitize tumors to GCV (35, 36). Treatment of tumor xenografts with the replication-competent Ad.TK-RC virus and GCV has been shown to prolong survival over that obtained with Ad.TK-RC alone (36). These results indicate that the lysis caused by the replicating virus and the suicide/prodrug therapy with HSV-tk/GCV results in improved antitumor activity. In the construction of Ad.DF3-E1, we inserted the CMV promoter in a direction opposite to that of the MUC1 promoter to drive additional transgenes. Importantly, the CMV promoter had no detectable effect on activity of the DF3 promoter. Placement of the GFP gene downstream of the CMV promoter resulted in the generation of Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-GFP, which replicates in MUC1-positive cells and expresses GFP. Although GFP could be replaced in this vector by HSV-tk or other suicide genes, we selected the TNF gene because of the selective antitumor activity of the TNF protein (18). Infection of MUC1-positive tumor cells with the Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF virus was associated with viral replication and selective expression of TNF as a consequence of viral production. In this context, both viral replication and TNF production were approximately 5 logs higher in MUC1-positive cells than in MUC1-negative cells. The results also demonstrate that treatment of MUC1-positive MCF-7 cells with Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF resulted in prolonged tumor regression compared with that obtained with Ad.DF3-E1 or Ad.CMV-TNF. In addition, Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF had little if any effect on growth of MUC1-negative MDA-MB-231 tumors. These findings indicate that the Ad.DF3-E1/CMV-TNF virus is competent for replication in MUC1-positive tumors and that it confers improved antitumor activity by expressing the TNF protein.

In summary, replication-competent viruses offer certain advantages over replication-defective vectors for cancer gene therapy when replication is controlled by tumor-selective regulatory sequences. The replication-competent viruses have the capacity to spread throughout the tumor mass and to express therapeutic gene products. Our results demonstrate that the MUC1 promoter confers competence for selective replication of Ad.DF3-E1 in MUC1-positive tumor cells, and that this vector can be used to express additional transgenes. Because MUC1 is overexpressed in diverse human carcinomas, recombinant Ad.DF3-E1 vectors are being developed that express other candidate therapeutic genes, including those encoding HSV-tk and cytosine deaminase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keiji Mitamura (Showa University, Tokyo, Japan) for his encouragement and support, as well as Tai Yu-Tzu and Tomonori Ishii (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), Tsuneya Ohno (Jikei University School of Medicine), and Masahiro Araki and Osamu Yamada (FUSO Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.) for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Haj-Ahmad Y, Graham F. Characterization of an adenovirus type 5 mutant carrying embedded inverted terminal repeats. Virology. 1986;153:22–34. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bett A, Haddara W, Prevec L, Graham F. An efficient and flexible system for construction of adenovirus vectors with insertions or deletions in early regions 1 and 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8802–8806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heise C, Kirn DH. Replication-selective adenoviruses as oncolytic agents. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:847–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI9762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez R, et al. Prostate attenuated replication competent adenovirus (ARCA) CN706: a selective cytotoxic for prostate-specific antigen-positive prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2559–2563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyatake S-I, et al. Hepatoma-specific antitumor activity of an albumin enhancer/promoter regulated herpes simplex virus in vivo. Gene Ther. 1999;6:564–572. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kufe D, et al. Differential reactivity of a novel monoclonal antibody (DF3) with human malignant versus benign breast tumors. Hybridoma. 1984;3:223–232. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1984.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe M, Kufe DW. Identification of a family of high molecular weight tumor-associated glycoproteins. J Immunol. 1987;139:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman EL, Hayes DF, Kufe DW. Reactivity of monoclonal antibody DF3 with a high molecular weight antigen expressed in human ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5189–5194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancaster CA, et al. Structure and expression of the human polymorphic epithelial mucin gene: an expressed VNTR unit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80888-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swallow D, et al. The hypervariable gene locus PUM, which codes for the tumour associated epithelial mucins, is located on chromosome 1, within the region 1q21-24. Ann Hum Genet. 1987;51:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1987.tb01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abe M, Kufe D. Transcriptional regulation of the DF3 gene expression in human MCF-7 breast carcinoma cells. J Cell Physiol. 1990;143:226–231. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041430205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovarik A, Peat N, Wilson D, Gendler S, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Analysis of the tissue-specific promoter of the MUC1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9917–9926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abe M, Kufe D. Characterization of cis-acting elements regulating transcription of the human DF3 breast carcinoma-associated antigen (MUC1) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:282–286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manome Y, Abe M, Hagen MF, Fine HA, Kufe DW. Enhancer sequences of the DF3 gene regulate expression of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene and confer sensitivity of human breast cancer cells to ganciclovir. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5408–5413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, et al. Breast cancer selective gene expression and therapy mediated by recombinant adenoviruses containing the DF3/MUC1 promoter. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2775–2782. doi: 10.1172/JCI118347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruder JT, Jie T, McVey DL, Kovesdi I. Expression of gp19K increases the persistence of transgene expression from an adenovirus vector in the mouse lung and liver. J Virol. 1997;71:7623–7628. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7623-7628.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang A, et al. Molecular cloning of the complementary DNA for human tumor necrosis factor. Science. 1985;12:149–154. doi: 10.1126/science.3856324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carswell E, et al. An endotoxin-induced serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3666–3670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hareuveni M, et al. Vaccination against tumor cells expressing breast cancer epithelial tumor antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9498–9502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho S, et al. Heterogeneity of mucin gene expression in the normal and neoplastic tissues. Cancer Res. 1993;53:641–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metzgar R, et al. Detection of a pancreatic cancer-associated antigen (DU-PAN-2 antigen) in serum and ascites of patients with adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5242–5246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarrard J, et al. MUC1 is a novel marker for the type II pneumocyte lineage during lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5582–5588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takamiya Y, et al. Gene therapy of malignant brain tumors: a rat glioma line bearing the herpes simplex virus type 1-thymidine kinase gene and wild type retrovirus kills other tumor cells. J Neurosci Res. 1992;33:493–503. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyatake S, Martuza R, Rabkin S. Defective herpes simplex virus vectors expressing thymidine kinase for treatment of the malignant glioma. Cancer Gene Ther. 1997;4:222–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dion L, et al. E1A RNA transcripts amplify adenovirus-mediated tumor reduction. Gene Ther. 1996;3:1021–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culver KW, et al. In vivo gene transfer with retroviral vector-producer cells for treatment of experimental brain tumors. Science. 1992;256:1550–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1317968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bischoff J, et al. An adenovirus mutant that replicates selectively in p53-deficient human tumor cells. Science. 1996;274:373–376. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heise C, Williams A, Xue S, Propst M, Kirn D. Intravenous administration of ONYX-015, a selectively replicating adenovirus, induces antitumoral efficacy. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2623–2628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heise C, et al. ONYX-015, an E1B gene-attenuated adenovirus, causes tumor-specific cytolysis and antitumoral efficacy that can be augmented by standard chemotherapeutic agents. Nat Med. 1997;3:639–645. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shinoura N, et al. Highly augmented cytopathic effect of a fiber-mutant EIB-defective adenovirus for gene therapy of gliomas. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3411–3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall A, Dix B, O’Carroll S, Braithwaite A. p53-dependent cell death/apoptosis is required for a productive adenovirus infection. Nat Med. 1998;4:1068–1072. doi: 10.1038/2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothmann T, Hengstermann A, Whitaker N, Scheffner M, Hausen H. Replication of ONYX-015, a potential anticancer adenovirus is independent of p53 status in tumor cells. J Virol. 1998;72:9470–9478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9470-9478.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodrum F, Ornelles D. p53 status does not determine outcome of E1B 55-kilodalton mutant adenovirus lytic infection. J Virol. 1998;72:9479–9490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9479-9490.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu D-C, Sakamoto G, Henderson D. Identification of the transcriptional regulatory sequences of human lallikrein 2 and their use in the construction of calydon virus 764, an attenuated replication competent adenovirus for prostate cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1498–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wildner O, et al. Adenovirus vectors capable of replication improve the efficacy of HSVtk/GCV suicide gene therapy of cancer. Gene Ther. 1999;6:57–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wildner O, Blaese R, Morris J. Therapy of colon cancer with oncolytic adenovirus is enhanced by the addition of herpes simplex virus-thymidine kinase. Cancer Res. 1999;59:410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]