Abstract

Classical epidemic theory focuses on directly transmitted pathogens, but many pathogens are instead transmitted when hosts encounter infectious particles. Theory has shown that for such diseases pathogen persistence time in the environment can strongly affect disease dynamics, but estimates of persistence time, and consequently tests of the theory, are extremely rare. We consider the consequences of persistence time for the dynamics of the gypsy moth baculovirus, a pathogen transmitted when larvae consume foliage contaminated with particles released from infectious cadavers. Using field-transmission experiments, we are able to estimate persistence time under natural conditions, and inserting our estimates into a standard epidemic model suggests that epidemics are often terminated by a combination of pupation and burnout, rather than by burnout alone as predicted by theory. Extending our models to allow for multiple generations, and including environmental transmission over the winter, suggests that the virus may survive over the long term even in the absence of complex persistence mechanisms, such as environmental reservoirs or covert infections. Our work suggests that estimates of persistence times can lead to a deeper understanding of environmentally transmitted pathogens, and illustrates the usefulness of experiments that are closely tied to mathematical models.

Subject headings: host-pathogen, Lymantria dispar, nucleopolyhedrovirus, threshold theorem, insect outbreaks, environmental transmission, complex dynamics

Introduction

In classical epidemic models, transmission results from contact between healthy and infectious hosts (Kermack and McKendrick 1927), but for many animal pathogens, transmission instead occurs when hosts contact infectious particles in the environment (Mathiason et al. 2009; Hall et al. 2005; Ebert et al. 1996). For such diseases, theory has shown that pathogen persistence time in the environment is an important determinant of whether an epidemic will occur (Breban et al. 2009), but applications of the theory require estimates of persistence times. Estimating persistence times from observations of disease spread in nature is difficult, because losses due to pathogen breakdown may be outweighed by gains due to pathogen particles produced from new infections (Woods and Elkinton 1987), making it hard to distinguish persistence from infectiousness. Meanwhile, field experiments that can disentangle persistence and infectiousness are often impossible (Dobson and Meagher 1996). Persistence-time estimates are therefore rare, and so applications of the theory are correspondingly rare.

For baculovirus diseases of insects in contrast, field experiments are entirely feasible (D’Amico and Elkinton 1995; Goulson et al. 1995; Hails et al. 2002; Georgievska et al. 2010). In many insects, baculoviruses are transmitted when larvae consume foliage contaminated with the infectious cadavers of other larvae, and infection generally leads to death (Cory and Myers 2003). This simple biology makes it possible to experimentally quantify transmission in the field (Dwyer 1991; Zhou et al. 2005; Elderd et al. 2008), and extending this type of experiment to also measure baculovirus persistence time is straightforward. We therefore used a field transmission experiment to estimate the persistence time of a baculovirus of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar, and we used our estimate in mathematical models to show how persistence time affects baculovirus epidemics and gypsy moth outbreaks.

Experiments that show evidence of baculovirus decay have a 45-year history (Jaques 1967), yet to our knowledge baculovirus persistence time under natural conditions in the field has never been estimated. Previous experiments generally did not consider estimation, instead simply testing whether a treatment alters the effect of exposure time on the infection rate (Jaques 1967, 1968, 1972; Broome et al. 1974; Elnagar and Abul-Nasr 1980; Biever and Hostetter 1985; Roland and Kaupp 1995; Webb et al. 1999, 2001; Raymond et al. 2005). Apparently as a result, most experiments were not designed in a way that permits separate estimation of persistence time and infectiousness, as we explain in the Appendix. Also, previous experiments have generally followed biological control programs in using purified virus (Hunter-Fujita et al. 1998), which may lead to artificially reduced persistence times. In our experiments, we mimicked natural transmission by using infectious cadavers, and comparing our estimate of persistence time to estimates based on data for purified virus (Webb et al. 1999, 2001) shows that purified gypsy-moth virus breaks down roughly twice as fast as infectious cadavers.

Our estimate of virus persistence time is important because it helps us to understand both virus epidemics and insect outbreaks. To show this, we first inserted our estimate into an epidemic model, modified to allow pupation to terminate transmission, and we compared the predictions of this model to two predictions of epidemic theory (Keeling and Rohani 2007). The first prediction is that there will be a minimum host population at which an epidemic will occur, the disease-density (or host-density) threshold. The second prediction is that epidemics will end because of a lack of infected hosts rather than because of a lack of susceptible hosts, so-called epidemic burnout. If persistence time is sufficiently high, however, the disease threshold may be so low that whether an epidemic occurs will be determined by the initial density of the pathogen instead of by the threshold. Alternatively, if persistence time is sufficiently low, epidemics will end because of host pupation rather than burnout. Our models show that the persistence time of the gypsy moth virus is short enough that the disease-density threshold is a useful statistic, but it is also short enough that pupation is often as important as burnout in ending epidemics.

These effects can modulate outbreaks because gypsy-moth population dynamics are partly driven by virus epidemics (Dwyer et al. 2004; Bjornstad et al. 2010). Extending our single-epidemic model to allow for multiple host generations shows that shorter persistence times produce less severe outbreaks. Moreover, our estimate of persistence time leads to long-term virus survival in the models, even though the models include only simple mechanisms of over-winter survival, notably external contamination of egg masses. This is important because efforts to explain long-term baculovirus persistence often emphasize more complex survival mechanisms, such as soil reservoirs (Thompson et al. 1981; Hochberg 1989; Fuxa and Richter 2007) and covert infections (Burden et al. 2003; Myers et al. 2000). Our model instead suggests that reservoirs and covert infections may not be necessary to explain baculovirus persistence, either in the gypsy moth or in other insects (Moreau and Lucarotti 2007).

Materials & Methods

Baculovirus Ecology and Epidemic Models

Like many outbreaking insects (Hunter 1991), gypsy moths have only one generation per year, with five instars (larval stages) in males and six in females. In southwestern Michigan, USA, where we carried out our experiments, larvae hatch in late April or early May. Pupation occurs in mid July, and the insect overwinters in the egg (Elkinton and Liebhold 1990).

In the spring, some hatchlings (or “neonates”) become infected, later releasing infectious occlusion bodies that begin the epidemic (Woods and Elkinton 1987). Uninfected larvae that consume a large enough dose of the virus die 7–21 days after infection, and release occlusion bodies onto the foliage for consumption by other larvae (Cory and Myers 2003). The most important round of transmission thus occurs when virus produced by infected neonates infects larvae in the third and fourth instars (Woods and Elkinton 1987). In our experiments, we therefore measured transmission from infected neonates to uninfected fourth instars.

Although models of directly transmitted diseases assume that transmission occurs only through contact between infected and uninfected hosts, we can nevertheless use such models for baculoviruses by using the infectious-host class in the models to represent infectious cadavers. The model that we use is therefore a modification of the well-known Susceptible-Exposed-Infected-Removed or “SEIR” model (Keeling and Rohani 2007), extended to allow for host heterogeneity in infection risk, an important factor in the transmission of the gypsy moth virus (Dwyer et al. 1997). This model is a variant of models previously used by the second and third authors, extended to allow for variance in the distribution of the time between infection and death, a variance that we previously assumed was very low (Dwyer and Elkinton 1993; Elderd et al. 2008). Because it allows for non-zero variance in this distribution, the model that we use here is slightly more realistic, and it has the advantage of being more stable when numerically integrated on a computer:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Here S is the density of uninfected or “susceptible” hosts, and P is the density of infectious cadavers. Gypsy moth larvae vary in the dose of virus needed to cause infection (Dwyer et al. 1997), as well as in feeding behavior (Parker et al. 2010), leading to variability in overall infection risk (Dwyer et al. 2005; Elderd et al. 2008). We therefore assume that transmission rates follow a probability distribution with mean ν̄ and coefficient of variation C. To describe the probability distribution that models the time between infection and death, we follow standard practice in dividing the exposed class Ei into m classes, such that the average speed of kill is 1/δ, and the rate at which individuals move from one class to the next is mδ (Keeling and Rohani 2007). The total time in the exposed classes is then equal to the sum of m exponential distributions, each with mean 1/(mδ). This sum follows a gamma distribution with mean 1/δ and variance 1/(mδ2), so that the variance declines as m increases. We can therefore control the variance on the distribution of speeds of kill by varying m. We assume 1/δ = 12 days, with m = 20, based on observations of speeds of kill of infected larvae (G. Dwyer, unpublished). This model requires integer values of m, but in our case changing m by 1 instead of, say, by 0.5, has only a tiny effect on the epidemic. Also, because hatchling larvae are much smaller than later instars, we allow for a simple form of stage structure by assuming that infected hatchlings produce smaller cadavers than later instars.

Once larvae reach the final exposed class m, they die and become infectious cadavers P. Cadavers break down at rate μ, so estimating μ was the goal of our experiments. The average persistence time of the virus is 1/μ, so that large values of μ produce short persistence times. Decay likely occurs because the virus is destroyed or inactivated by the ultraviolet rays in sunlight (Ignoffo et al. 1977), but the virus may also be washed off foliage by rain (D’Amico and Elkinton 1995). Versions of this model have survived extensive testing with both experimental and observational data for the gypsy-moth virus (Dwyer and Elkinton 1993; Dwyer et al. 1997, 2005; Elderd et al. 2008). We therefore use it to understand the implications of our parameter estimates.

Field Experiments

Field observations of baculovirus populations cannot easily be used to estimate decay rates, because losses of virus due to decay are often offset by inputs of virus due to new virus-caused deaths (Woods and Elkinton 1987). Previous field studies have therefore simply observed that virus is present at two points in time, usually one immediately following an epidemic and one a year or more later, with the conclusion that virus particles can sometimes survive for a year or more (Tanada and Omi 1974; Young et al. 1977; Entwistle and Adams 1977; Podgwaite et al. 1979; Olofsson 1988).

An experimental approach might therefore be more effective, but most experiments that vary exposure time have used only a single virus density (Broome et al. 1974; Biever and Hostetter 1985; Elnagar and Abul-Nasr 1980; Raymond et al. 2005). As we show in the Appendix, these single-density experiments generally preclude estimation of decay rates using standard models. In standard models, infection rates are a nonlinear function of both exposure time and virus density, and the effects of the two cannot be distinguished unless they are varied independently (Sun et al. (2004) avoid this problem by instead back-calculating virus densities using dose-response data collected in an additional experiment, but their approach may underestimate parameter uncertainty (Appendix)). The few experiments that varied virus density and exposure time independently did not attempt to estimate the decay rate (Jaques 1967, 1972; Webb et al. 1999, 2001), possibly because of the difficulties of using the nonlinear fitting routines that are required for estimating parameters from fractional data. Also, experiments with baculoviruses have historically used purified virus, because the point of many experiments is to test insecticidal sprays, which usually incorporate only purified virus, and because some authors have perhaps assumed that infectious cadavers would produce data that are so noisy as to be un-interpretable. An important feature of natural transmission, however, is that infectious cadavers include insect body parts that may block UV (Capinera et al. 1976), and so experiments using purified virus may produce artificially inflated estimates of the decay rate. The use of infectious cadavers is therefore increasingly common, but for all the infectious-cadaver experiments of which we are aware, it is unclear whether the initially infected larvae were all dead when decay began, so virus inputs and virus losses probably occurred at the same time (Goulson et al. 1995; Hails et al. 2002; Zhou et al. 2005; Georgievska et al. 2010, the one exception, Roland and Kaupp (1995), only compared decay inside a forest to decay on the edge of the forest, and so included neither exposure-time treatments nor density treatments, and therefore also cannot be used to estimate decay time). Data from such experiments has the same problem as data from observations of epidemics, namely that decay is confounded with transmission, and apparently as a result in some cases it was impossible to detect the effects of exposure time (Goulson et al. 1995; Hails et al. 2002).

Our experiments were designed to circumvent these difficulties. First, to avoid an inflated estimate of natural decay, we used infectious cadavers. We then used 6–8 replicates of each treatment, depending on the experiment, which was enough that the uncertainty in our data was reasonably low, in turn permitting detection of virus decay. Meanwhile, two previous purified-virus experiments produced useable decay data for the gypsy moth-baculovirus (Webb et al. 1999, 2001), and reanalysis of those data confirmed that purified virus does indeed have a significantly shorter persistence time than infectious cadavers. Using infectious cadavers also allowed us to more accurately estimate the transmission rate ν̄, which we needed to estimate the density threshold. Because ν̄ is essentially infection risk, it is affected by feeding behavior (Dwyer et al. 2005), including the ability of gypsy moth larvae to detect and avoid infectious cadavers (Capinera et al. 1976; Parker et al. 2010). Unbiased estimation of ν̄ therefore required that we allow larvae to feed on virus-contaminated foliage under natural conditions, and so again it was important to use infectious cadavers.

Second, to avoid the obscuring effects of additions of virus while decay is occurring, we only allowed decay to begin after all of the initially infected larvae were dead. To do this, we placed the infected larvae on the foliage, and we enclosed larvae and foliage in mesh bags. The bags were necessary to prevent larvae from dispersing to other branches, but as we will show, they also effectively prevented decay. Once we were sure that the infected larvae were dead, we allowed for decay by removing the bags. After the virus had decayed for the requisite time, we added healthy larvae to the foliage, using new bags, which prevented further decay during transmission. To prevent later additions of virus due to the deaths of secondarily infected larvae, we only allowed the uninfected larvae to feed for one week, a period short enough that no secondarily infected larvae died during the experiment. At the end of the week, we removed the initially uninfected larvae to the lab, terminating transmission, and we recorded the number of larvae dying of the virus. Our experiments therefore allowed for only one round of transmission (note that our epidemic model, equations (1)–(4), in contrast allows for multiple rounds of infection, but this difference does not restrict our analyses in any way). We then used the fraction infected to estimate the transmission parameters ν̄ and C and the viral decay rate μ by fitting the model equations (1)–(4) to the data.

To ensure that the initially uninfected larvae were indeed uninfected, we reared them in the lab on artificial diet using surface-disinfected eggs. Surface disinfection for 90 minutes in 10% formalin is effective in preventing infection (Doane 1969; Elderd et al. 2008). Because small differences in developmental stage within an instar can alter susceptibility (Grove and Hoover 2007), we synchronized larvae by collecting them shortly before eclosion to the fourth instar, holding them for 24–48 hours at 4°C until we had enough larvae to carry out an experiment, and then allowing all larvae to molt to the fourth instar at room temperature. The effect was that all of our uninfected larvae molted to the 4th instar within roughly 24 hours of each other.

To produce infected larvae, we placed neonates in cups with diet contaminated with a high virus dose (Dwyer et al. 2005). By using a plaque-purified virus clone, we ensured that variability in the virus would play little role (Elderd et al. 2008). We then held these infected larvae at 28°C for 5 days, before placing them on foliage in the field. Because infected neonates do not molt to the second instar (Park et al. 1996), it was possible to identify and discard the small number of larvae that did not become infected. Because our emphasis was on estimating the decay rate rather than heterogeneity in infection risk, we reduced heterogeneity by using larvae from a USDA colony that has been reared in the laboratory for decades (Dwyer et al. 1997).

The infected larvae were placed on leaves of naturally occurring red oaks (Quercus rubra), a “most-favored” host plant of the gypsy moth (Barbosa and Krischik 1987). Experimental trees were located in the Lux Arbor Reserve of the Kellogg Biological Station, in Delton, Michigan, USA (42°28′ N, 85°28′ W). This site had negligible levels of gypsy moths or virus during the years of our study (Elderd et al. 2008). Each larva-laden branch was enclosed within bags made of spun-bonded polyester or “Reemay”, which has only modest effects on humidity and temperature (Lipman et al. 1992). We used virus densities of 25 and 50 cadavers per branch, a range that is sufficient to produce measurable infection rates (Dwyer et al. 2005), and that falls within the range of densities observed in nature (Woods and Elkinton 1987). We also included a control treatment containing no infected larvae, to test whether infections could be due to naturally occurring virus. Infection rates on the control branches were close to zero.

Five days after deployment the infected larvae were all dead, and so we removed the bags from the branches, exposing the virus-contaminated foliage to the environment. Because, as we will show, decay inside the bags is negligible, no decay occurred until the bags were removed from the foliage, so all virus had already been added to the foliage when decay began. We used exposure times of 0, 1, 3, and 7 days in 2007, each replicated 6 times, but the 2007 data suggested that our estimates would be more accurate if we used more replicates and eliminated the longest exposure-time treatment, so in 2008 we used treatments of 0, 1 and 3 days, each replicated 8 times. After exposing the cadavers, we enclosed the branches within new bags to prevent transmission through contact with the mesh, and we released 20 uninfected 4th instars onto each branch. We allowed the uninfected larvae to feed for 7 days, after which we placed them in individual diet cups for three weeks to determine if they were infected. Infected larvae are usually recognizable because they liquefy, but in cases of uncertainty we examined larvae under a light microscope, where the occlusion bodies were clearly visible at 400× (Miller 1997).

In 2007, many initially uninfected larvae were lost to predation by other insects, notably stink bugs (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae), and in any case the experimental design was still rough. In 2008 we used a more powerful design and stink-bug predation was low, and so our estimate of the decay rate from 2008 is thus more reliable. As we will show, however, virus decay was detectable in both years, and so we include both data sets. Also, in 2007 the experiment was carried out in July, while in 2008 the experiment was carried out in June, but previous work has made clear that the timing of this type of experiment within the summer has no effect on the results (Dwyer et al. 2005).

Statistical Tests

To estimate the decay rate μ and the transmission parameters ν̄ and C, we simplified the single-epidemic model to match the conditions of our experiments. After the uninfected larvae were placed on the branches, no more virus was added, and as we will show the virus does not decay while the foliage is in a bag, so we can set the rate of change of infectious cadavers inside the bags . We allowed virus transmission for 7 days (t̂ = 7) and so we integrate equation (1) for the host population from 0 to t̂. Equation (1) can then be solved to give the fraction of susceptible hosts S remaining after transmission has ended (Appendix). Because our main interest was in detecting virus decay, our statistical analyses were designed to determine if allowing for μ > 0 improved the model’s fit to the data. We therefore considered two versions of the model, one with μ > 0 and one with μ = 0. If we assume μ > 0, we have:

| (5) |

If we assume μ = 0, we have:

| (6) |

Here S(0) and S(t̂) are the densities of uninfected hosts at the beginning and the end of the transmission period, respectively. The initial density of infectious cadavers is then P(0), and T is the length of time that virus-contaminated leaves were exposed to the environment before transmission began. Following equation (4) for the infectious-cadaver population, we thus assume that, in the absence of new virus deaths, the virus population decays exponentially when exposed to the environment.

Monte-Carlo simulations have shown that estimates of heterogeneity C using this type of experiment have smaller confidence intervals if the experiment includes a larger number of virus densities (G. Dwyer, unpublished). Because our emphasis was on estimating the decay rate μ, however, we sacrificed a larger number of virus densities in favor of a larger number of exposure-time treatments. Similarly, values of C tend to be higher for feral larvae than for laboratory larvae (Dwyer et al. 1997, 2005), but because of our emphasis on estimating the decay rate, we used laboratory larvae to reduce overall variability and so to increase statistical power. Consequently, as we will show, models that assume C → 0 fit our data better than models that assume C > 0. If we allow C → 0, then the model for μ > 0 is:

| (7) |

whereas for μ = 0, the model is:

| (8) |

In fact, 11 previous experiments by the second and third authors and colleagues have demonstrated that, for the gypsy moth, heterogeneity C > 0, even for laboratory larvae (Dwyer et al. 1997, 2005; Elderd et al. 2008). Accordingly, even though in the interests of statistical rigor we emphasize the fit of models for which C = 0, we also report results for the case for which C > 0. Fortunately, our estimates of the decay rate μ in the two cases are very similar.

In our statistical models we assume that no virus decay occurs within the mesh bags. To test this, in 2007 we included a treatment in which all infected larvae were dead 7 days before the experiment began, but for which the infectious cadavers were never exposed to the environment. We thus allowed for a week of virus decay, but only within a bag (although we again put new bags on before adding uninfected larvae, as in the other treatments). As with the other treatments, this additional treatment was replicated 6 times. For the 2007 data, we therefore included a model with a separate rate for decay inside the bag (see Appendix for the models).

To estimate μ, ν̄, and C in equations (5)–(8), we fit each equation to the data using maximum likelihood, using the nonlinear-fitting routines optim and optimize in the R programming language (R Development Core Team 2009). We used a binomial likelihood function, as is appropriate for mortality data (McCullagh and Nelder 1989), but to allow for the possibility of over-dispersion, we calculated a variance-inflation factor (Burnham and Anderson 2002). The variance-inflation factor is the goodness-of-fit chi-squared statistic (χ2) of the global model, in this case equation (5), divided by the degrees of freedom (McCullagh and Nelder 1989). For the 2007 data the variance-inflation factor was 2.23, while for the 2008 data it was 1.89. These values are small enough (<4) to suggest that there was no systematic lack of fit, but large enough that we used them to adjust our AICc values, by dividing each AICc value by the variance inflation factor (Burnham and Anderson 2002). This statistic is known as the Quasi-likelihood AIC, or QAICc, but for brevity we refer to it as an AICc score. By choosing the best model using the AICc, we tested whether the models that assume μ > 0 provide a better explanation for the data than the models that assume μ = 0. The lower the AICc score, the better the model (Burnham and Anderson 2002).

We calculated 95% confidence intervals on the decay rate μ using bootstrapping (Efron and Tibshirani 1994), to determine if the confidence intervals overlapped 0. To do this we randomly selected replicates with replacement from within a given year’s data, until we had as many replicates as used in that year, and then we recalculated the parameter values. This procedure was repeated 1,000 times and the resulting distribution provided 95% confidence intervals for each parameter.

We also estimated the decay rate of purified gypsy moth virus by re-analyzing data from Webb et al. (1999, 2001). In these experiments, purified virus was sprayed on foliage of “mostly” pin oak, Quercus palustris (other tree species were not named), in combination with water and bond sticker (we did not consider treatments in which any other compounds were added to the spray, such as Blankophor BBH, because of our interest in natural transmission), and uninfected larvae were added to the foliage at 0 and 1 week after virus application in 1999, and at 0, 1 and 2 weeks in 2001. Because of these small differences, comparisons between our estimate and the estimate for the Webb et al. data are not definitive, but they provide an interesting comparison. We analyzed the data using essentially the same methods that we used for our own data (some small differences are described in the Appendix). In the Webb et al. (2001) paper, the data were analyzed in such a way that some treatment-specific standard errors were not reported, and so in making inferences we focus on the Webb et al. (1999) data.

Long-Term Dynamics

In our experiments, we measured the survival time of the virus on foliage. Because the gypsy-moth feeds on deciduous trees, survival on foliage is unlikely to be an effective over-winter persistence mechanism. Nevertheless, as we will show, survival on foliage also affects long-term dynamics, because its effects on epidemics lead to effects on the size of the host population. To show this, we extended our single-epidemic model to allow for long-term dynamics. Allowing for long-term dynamics required that we estimate pathogen persistence over the winter. Possible over-winter persistence mechanisms include soil reservoirs, covert infections, survival in the larval environment, and contamination of egg masses.

In empirical investigations of baculovirus persistence in soil reservoirs, transmission has only been measured in the lab. The typical approach is to add material from the field, such as soil or duff from the forest floor, to distilled water (Podgwaite et al. 1979; Thompson et al. 1981), and then to feed the resulting solution to larvae in the lab. The occurrence of infections then indicates that the virus is present, but for such virus to cause infections in nature, it would have to be translocated to the foliage so that larvae can eat it (Thompson et al. 1981; Fuxa and Richter 2007). Because one of the motivating principles of our work is that persistence time is best studied through its effects on transmission in the field, we do not consider persistence mechanisms for which there is no evidence of field transmission. We therefore do not attempt to estimate survival rates from existing data on soil reservoirs.

Similar difficulties hold for another survival mechanism, covert infections, in which a host harbors a virus but shows no signs of infection (Il’inykh and Ul’yanova 2005). If such latent virus is activated, the host may die of the infection, leading to horizontal transmission that may spark an epidemic. Existing data consist of observations of virus outbreaks in laboratory populations held under sterile conditions (Burden et al. 2006), and detection, using PCR, of viral DNA in individuals in the field (Burden et al. 2003; Kouassi et al. 2009; Vilaplana et al. 2010). The latter data often reveal high latent infection rates, and so covert infections would seem to have the potential to play an important role in baculovirus dynamics. The rate at which covert infections convert to overt infections in nature, however, is unknown.

Moreover, for the gypsy moth in particular, evidence for covert infections is weak. Surface disinfection of egg masses in the third author’s lab reduced contamination in lab larvae to two apparently unexposed individuals out of roughly 105 insects over eight years. Data cited as evidence in favor of covert infections in contrast are derived either from non-disinfected egg masses (Myers et al. 2000), or from stressing larvae from disinfected eggs in the laboratory, on the theory that stressors may activate latent virus (Ilyinykh et al. 2004). In the latter study, the stressor shown to elevate infection rates in gypsy moths was copper sulfate, whereas natural stressors such as cold temperatures, high densities, or hatching delays, had no effect (Ilyinykh et al. 2004). Moreover, infection rates in controls were never zero, and so copper sulfate may simply lower resistance. The rate at which covert infections produce overt infections therefore appears to be very low in gypsy moths. More immediately, existing data do not meet our criterion of showing effects on transmission in the field.

Evidence for over-wintering through survival on bark, or through egg-mass contamination, is in contrast quite strong. First, Woods et al. (1989) showed that virus on bark can lead to infection when larvae walk over contaminated bark and then transfer the virus to the foliage. Survival on bark thus meets our criterion of providing evidence of transmission in the field. We therefore use Podgwaite et al. (1979)’s rough estimate that survival on bark is less than 1% per year. As we will show, this parameter has a small enough effect on the dynamics that the difference in effects between a minimum of 0% survival and a maximum of 1% is slight.

Evidence for the importance of external contamination of egg masses is even stronger (Doane 1970). Part of the evidence is again that surface-sterilization of field-collected egg masses reduces infection rates from high values to values near 0 (Doane 1969; Elderd et al. 2008). Moreover, Murray and Elkinton (1989) provide direct experimental evidence that egg mass contamination occurs as a result of eggs being laid on contaminated bark. They transferred egg masses between field populations that had had virus epidemics of different intensities in the previous season, to show that the fraction hatching infected was significantly higher when eggs were laid at a high-virus site. In contrast, there was no effect of the site that eggs were moved to after laying. More generally, infection rates among larvae hatching from naturally occurring eggs laid at the high-virus site averaged 55%, suggesting that egg-mass contamination can lead to high rates of over-winter survival. We therefore use Murray and Elkinton’s data to estimate the rate of over-winter transmission due to egg-mass contamination (Online Appendix).

In our long-term model, we thus allow for virus over-wintering due to either egg-mass contamination or survival in the environment, and we leave out covert infections and soil reservoirs. Our models are therefore perhaps less general than some models in the literature (Bonsall et al. 2005; Boots et al. 2003; Sorrell et al. 2009), in that we do not consider every possible over-wintering mechanism. A focus on mechanisms supported by field data, however, has the advantage of producing a more parsimonious model. To the extent that our models show long-term virus persistence, we can argue more strongly that some persistence mechanisms may not be necessary for explaining baculovirus persistence in nature.

Our long-term model is:

| (9) |

| (10) |

Here Nn and Zn are the densities of insects and infectious cadavers, respectively, before the epidemic in generation n, and i(Nn; Zn) is the fraction of larvae that become infected. The symbol λ is the net reproductive rate, while εt is a normally distributed random variable with mean 0, representing the environmental stochasticity that often affects insect populations. The symbol f is the over-winter survival rate of virus produced in the previous generation, and γ is the over-winter survival of virus from previous generations. Our expectation is that f represents egg-mass contamination and that γ represents survival on bark, but in fact the model is more general than these interpretations. Although we do not expect that virus that is more than one year old will have a different survival rate, as we will show, it is conceptually useful to model these rates separately. Also, for many outbreaking insects, generalist predators and parasitoids can play a crucial role in keeping inter-outbreak populations low (Dwyer et al. 2004), and so we allow for a Type-III predation term. Because we track the fraction surviving, the term then describes the fraction of hosts that survive predation, with a the maximum predation rate, and b the saturation constant on the functional response of the predator. To allow for a range of possibilities, we consider models with and without the predator, setting the predation rate a ≡0 to eliminate predation.

Previous work using versions of this model relied on the burnout approximation (below), to describe the fraction infected (Dwyer et al. 2004; Bjornstad et al. 2010). Under the burnout approximation, the decay rate μ and the transmission rate ν̄ affect only the scale of host population density, meaning that they do not affect the period or amplitude of outbreaks, nor whether outbreaks occur (Dwyer et al. 2004). Here we instead allow pupation to terminate epidemics, so that we use equations (1)–(4) with the epidemic length set to 56 days, roughly the length of the larval period in gypsy moths. For this model, re-scaling eliminates average transmission ν̄ but not the decay parameter μ (Online Appendix), and as we show in the Results section changes in the decay rate can therefore affect the amplitude of outbreaks.

To understand the relative importance of egg-mass contamination and survival in the environment, it is worth examining the re-scaled equation for the pathogen population:

| (11) |

Here the host and pathogen densities have been re-scaled according to N̂n ≡ ν̄Nn and Ẑn ≡ ν̄ηZn. We can then see that the virus-survival parameter f and the hatchling susceptibility parameter η affect the dynamics only as a product, and so we define φ ≡ fη to be the over-winter impact of the pathogen. To understand the importance of the difference between φ and γ, we note first that φN̂ni(N̂n; Ẑn) is the contribution to the virus population of infectious cadavers from the epidemic in the previous generation, whereas γẐn is the contribution from generations before that. The parameter φ thus describes only the impact of cadavers from the previous generation, which we again interpret as egg-mass contamination, whereas γ describes only the impact of cadavers from earlier generations, which we interpret as survival in the environment. Because it is likely that η is at least 100, it is possible that φ > 1 (shortly we will show that φ is at least 3), whereas by definition γ is less than 1. The effect of small increases in f, the survival of cadavers from the previous generation, is thus greatly amplified by the effects of η, the relative susceptibility of hatchlings. We therefore expect that the survival of cadavers from the previous generation will have a much stronger effect on outbreaks than will the survival of cadavers from earlier generations.

Results

Experiments

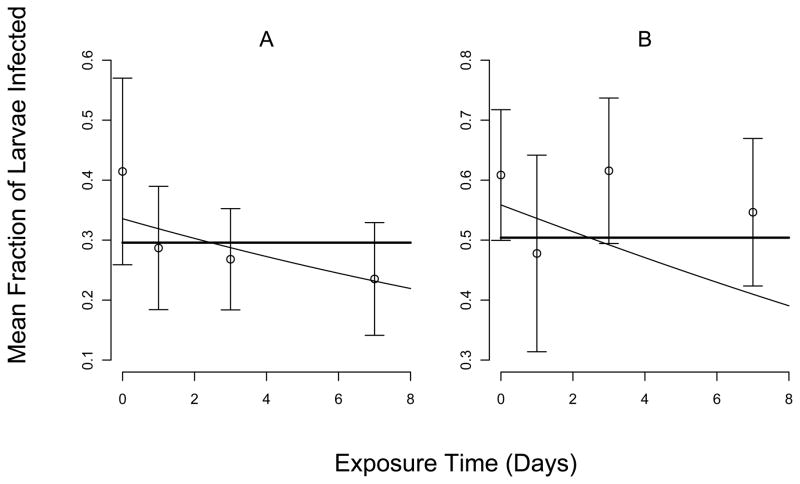

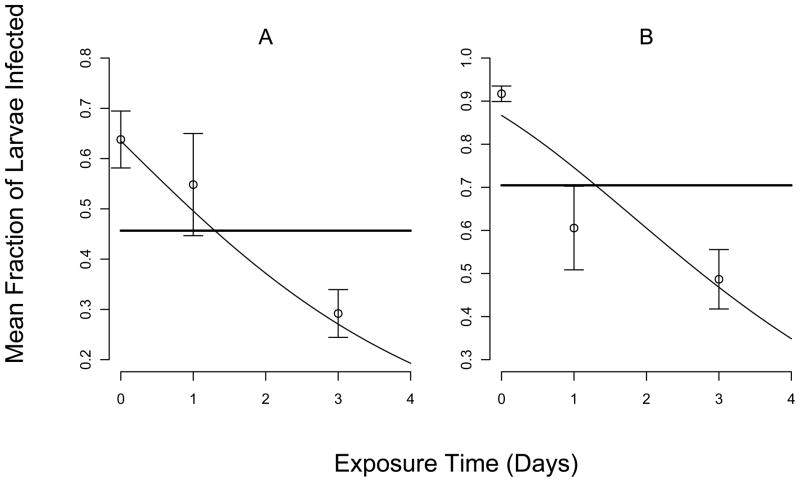

As we expected, in both years, the infection rate was lower in the 25-cadaver treatment than in the 50-cadaver treatment (figs. 1 and 2). More importantly, in both experiments, at both virus densities, the fraction infected generally declined with increasing exposure time. The standard errors for 2007, however, were much larger than for 2008, probably because of the reduction in sample size that resulted from stink-bug predation.

Figure 1.

Comparison of best-fit model prediction to data from 2007. Data (points) show the mean fraction infected, with one standard error of the mean. Curves show the best-fit model predictions, such that the thin line is for μ > 0, equation (7), and the thick line is for μ = 0, equation (8). Panel (A) shows the results for 25 cadavers per branch, while (B) shows the results for 50 cadavers per branch. To illustrate the fit of the models, we use different vertical axis scales for the two panels.

Figure 2.

Comparison of best-fit model prediction to data from 2008. Points and lines are as in fig. 1, and again the vertical axis scales are different for the two panels. Panel (A) again shows the results for 25 cadavers per branch, while (B) again shows the results for 50 cadavers per branch.

AIC analysis confirmed that the models that included the decay rate μ, equations (5) and (7), gave a better fit to the data than the models that assumed μ = 0, equations (6) and (8) (Table 2). In 2007, the best model included decay both outside the bags and inside the bags, but the decay rate inside the bag was so low as to be negligible (Table 3). Also, in 2007 the AIC difference between the best model and a model with no decay was less than 2, indicating that models that exclude decay provide nearly as good an explanation for the data as models that do not include decay. This lack of discriminatory power in the 2007 data is probably due either to the uncertainty introduced by stink-bug predation, or to the less powerful experimental design. The ΔAICc score for the model with C > 0 was similarly 2 or less in both years, suggesting that the models with heterogeneity explain the data nearly as well as the models without heterogeneity. Fortunately, our best estimates of μ are nearly the same irrespective of whether we assume C > 0 (Table 3). Although our best estimate of the average viral lifetime from the 2007 data was 14.3 days, the 95% confidence interval includes 6.19 days and 26.2 days (Table 3). Our estimate from the 2008 data of 2.56 days therefore appears to be more reliable.

Table 2.

AICc values for the models with and without decay rates. Values for the best model in each year are in bold face.

| Year | Decay? | Heterogeneity? | In-bag decay? | Number parameters (K) | QAICC Value | Δ QAICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | No | No | No | 1 | 89.57 | 0.31 |

| Yes | No | No | 2 | 90.07 | 0.81 | |

| No | Yes | No | 2 | 91.58 | 2.32 | |

| Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 92.00 | 0.73 | |

| Yes | No | Yes | 3 | 89.26 | 0 | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 91.27 | 2.01 | |

|

| ||||||

| 2008 | No | No | – | 1 | 108.11 | 43.85 |

| Yes | No | – | 2 | 64.26 | 0 | |

| No | Yes | – | 2 | 107.68 | 43.42 | |

| Yes | Yes | – | 3 | 66.30 | 2.04 | |

Table 3.

Best-fit model parameter values for our experiments, and for the experiments of Webb et al. (1999, 2001). Note that the transmission parameters for the Webb et al. data depend on a long list of assumptions, and thus are not very reliable (Appendix). For the Webb et al. data, we therefore do not include an estimate of the threshold. The upper confidence bound on the decay rate for the Webb et al. (2001) data is also probably unreliable (Appendix).

| Field Season | Transmission ν̄ | Decay μ | In-bag decay | Htg. C | Avg. persistence | Population Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m2/day | day−1 | day−1 | days | Insects per m2 | ||

| 2007 | 0.24 (0.17, 0.32) | 0.04 (10−8, 0.093) | – | – | 25 (10.7, 107) | 0.17 (10−7, 0.35) |

| 2007 | 0.28 (0.18, 0.55) | 0.054 (10−7, 0.13) | – | 0.56 (10−4, 1.67) | 18.5 (7.67, 106) | 0.19 (10−7,0.33) |

| 2007 | 0.26 (0.19,0.40) | 0.07 (0.03,0.11) | 10−7 (10−10,0.08) | – | 14.3 (6.19,26.6) | 0.27 (0.11,0.39) |

| 2007 | 0.30 (0.20,0.67) | 0.07 (0.04,0.16) | 10−8 (10−9,0.08) | 0.65 (10−4,1.67) | 14.3 (6.19,26.6) | 0.24 (0.11,0.36) |

|

| ||||||

| 2008 | 0.64 (0.54, 0.79) | 0.39 (0.24, 0.51) | – | – | 2.59 (1.94, 3.95) | 0.61 (0.41, 0.81) |

| 2008 | 0.73 (0.54, 1.30) | 0.41 (0.25, 0.64) | – | 0.43 (3e-4, 0.93) | 2.43 (1.59, 3.82) | 0.61 (0.41, 0.81) |

|

| ||||||

| Webb et al. ’99 | 1470 (186, 105) | 1.09 (0.822,1.67) | – | 2.41 (1.95,3.05) | 0.91 (0.60, 0.91) | NA |

| Webb et al. ’01 | 55.9 (36.3,110) | 0.92 (0.83, 8.47) | – | 1.01 (0.118, 1.21) | 1.47 (1.23, 1.65) | NA |

Table 3 also shows that the decay rates from Webb et al. (1999, 2001), based on purified virus, are at least 2× higher than our decay rates based on infectious cadavers, and the confidence intervals do not overlap. Small differences between studies make it difficult to be conclusive, but the comparison provides preliminary evidence that purified virus decays faster. Moreover, persistence times for purified virus of other insects are also generally less than a day (Jaques 1967, 1972; Sun et al. 2004, see Appendix for estimates from the Jaques data). Purified virus of other insects therefore also appears to break down quite rapidly.

A related point is that accurate calculation of the transmission rate ν̄ from the Webb et al. experiments is difficult because important details such as leaf area were not provided. We made conservative assumptions in several cases of uncertainty (Appendix), but the resulting estimates are nevertheless orders of magnitude higher than the estimates from our experiments. Part of the explanation is probably that the virus in the Webb et al. experiments was applied uniformly over the leaf, which can raise infection rates (D’Amico et al. 2005), and also that larvae cannot easily detect and avoid purified virus (V. D’Amico, unpublished). The estimate of the decay rate μ, however, is unaffected by errors in the estimation of ν̄.

The Usefulness of The Disease-Density Threshold and The Burnout Approximation

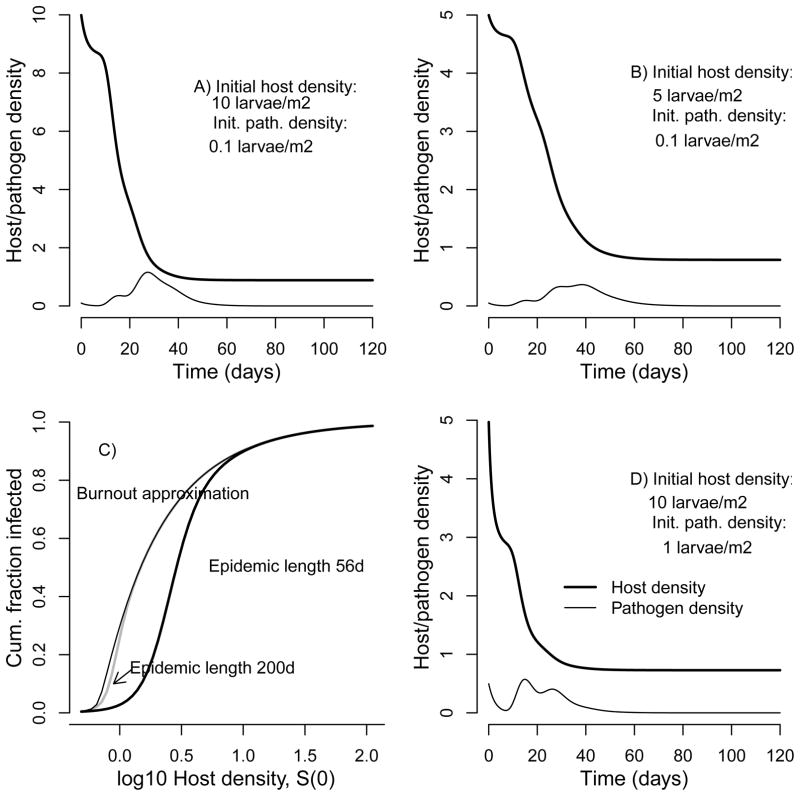

We next use our estimates of the transmission rate ν̄ and the decay rate μ in our single-epidemic model, equations (1)–(4), first using only our 2008 estimate for purposes of exposition, but shortly considering a range of values. As figs. 3A and B show, the pathogen begins at a low density, but ultimately it reaches a high enough density to cause the density of uninfected hosts S to drop rapidly (the complex fluctuations in the pathogen population reflect the time delay between infection and death, which introduces a kind of stage structure into the infected population (not shown)). Eventually depletion of the susceptible population causes viral decay to outweigh transmission, so that the density of cadavers drops towards zero, leaving behind a reduced but non-zero host population.

Figure 3.

Predictions of the epidemic-model equations (1)–(4) for parameters estimated from our data. (A) and (B) show trajectories for two different sets of initial host and pathogen densities, one with higher initial host density (A) and one with lower initial host density (B), and with the initial pathogen population equal to 1% of the host population in both. Cumulative fractions infected are A: 0.918, and B: 0.841. Transmission and decay are estimated from our 2008 data (ν̄ = 0.64 m2, μ = 0.39d−1), while heterogeneity is from previous experiments (C = 1.5) (Dwyer et al. 2005). Hatching larvae are assumed to be a fraction 0.02 of the size of later instar larvae, following an estimate of the number of occlusion bodies per fourth instar of 2 × 109 for fourth instars (Shapiro et al. 1979), and an estimate of 3.8 × 107 (±0.89 × 107) for neonates (G. Dwyer, unpublished). (C) compares the burnout approximation, equation 12, to the burnout-plus-pupation model for two different times of pupation, 250 and 56d. (D) is like (B), except that the initial virus density is 10% of the host population. Cumulative fraction infected: 0.854.

In figs. 3A and B, the initial host densities are typical of the low end of densities at which baculovirus epidemics have been observed (Woods and Elkinton 1987). These populations are nevertheless far enough above the disease-density threshold that overall mortality is quite high. It is possible to prove, however, that the host population in the model will never reach 0, even if the population starts yet farther above the threshold and time goes to infinity (Thieme 2003). In the absence of pupation, epidemics in the model are thus terminated when the infected population reaches 0, rather than because there are no more uninfected hosts, which is the phenomenon known as epidemic burnout (Keeling and Rohani 2007).

The fraction of hosts i that remain uninfected after burnout can be calculated from the implicit equation (Thieme 2003; Dwyer et al. 2000):

| (12) |

Mathematically, this result requires that we allow t → ∞, but as the trajectories in fig. 3A and B indicate, in most cases the epidemic is over for t ≪ ∞. In fig. 3B, for example, the epidemic is effectively over by t = 80 days. For gypsy moths and other outbreaking insects, however, larval periods are typically much less than 80 days (Moreau and Lucarotti 2007). It therefore seemed likely that the burnout approximation would provide only a rough description of epidemic severity in these insects.

To show the effect of epidemic length on the accuracy of the burnout approximation, in fig. 3C we plot the cumulative fraction infected i versus host density. Fig. 3C also shows the corresponding predictions of equations (1)–(4), assuming that the epidemic is terminated by pupation either at 250 or at 56 days, with the latter value appropriate for the gypsy moth. The burnout approximation is quite close to the 250-day case, but it is quite far from the 56-day case. It therefore appears that both pupation and burnout will limit epidemics, at least at low virus densities.

Fig. 3C also roughly illustrates the effect of the disease threshold, the lowest host density at which a negligible initial pathogen density, P(0) → 0, produces new infections (Thieme 2003). For equations (1)–(4), the threshold is , which from our 2008 data is 0.61 larvae/m2. In fig. 3C, a modest number of infections occur below this threshold because we have assumed an initial pathogen population equal to 1% of the host population, a value that is not that close to 0.

Allowing for both the 2007 and 2008 data, our estimates of the threshold range from 0.17 to 0.61 larvae/m2 (Table 3), whereas the lowest density at which an epidemic has been observed in nature is roughly 3 larvae/m2 (Dwyer and Elkinton 1993). Observational studies, however, are likely to over-estimate the population threshold, because stochastic effects near the threshold will reduce infection rates (Lloyd-Smith et al. 2005) and because it is difficult to find enough insects to estimate the fraction infected at low densities (Woods and Elkinton 1987). Moreover, in gypsy moths, host and virus densities are positively correlated. Indeed, at the lowest density at which an epidemic has been observed in nature, the cumulative infection rate was higher than 0.2 even though the initial infection rate was low, suggesting that such populations are well above the threshold (Woods et al. 1991). We therefore suspect that our best threshold estimate of 0.61 larvae/m2 is reasonably accurate.

In fig. 3C, we assumed an initial infection rate of 1% so as not to completely obscure the density threshold, but epidemics in gypsy-moth populations typically begin with initial infection rates of 10% or more (Woods et al. 1991). This is important because increasing the initial infection rate causes the epidemic to burn out more rapidly (fig. 3D), reducing the inaccuracy of the burnout approximation.

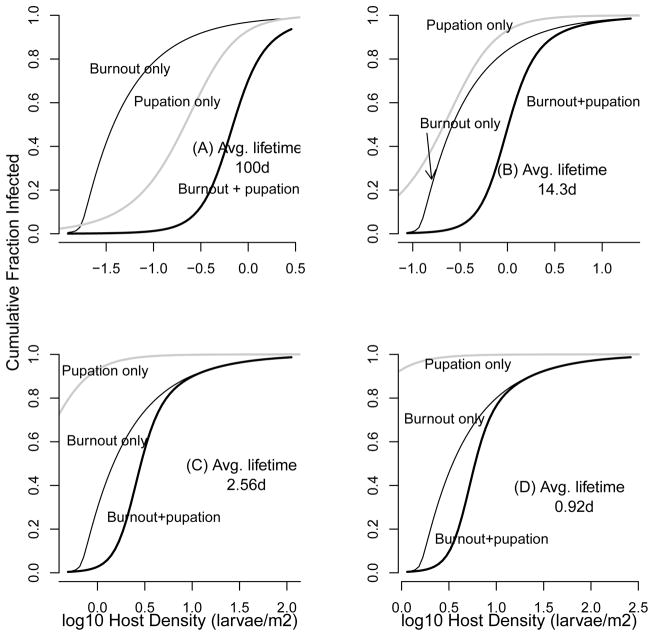

In considering a range of decay rates, we therefore instead assume that the initial pathogen population is equal to 10% of the initial host population. In fig. 4, we then compare our model predictions to the prediction of the burnout approximation, and to the predictions of a model in which decay is 0 and transmission is terminated only by pupation. In the figure, we use our point estimates of persistence from both 2007 (14.3 days) and 2008 (2.56 days), as well as an estimate from the Webb et al. (1999) data, and a high value of 100 days to allow for a case of near-zero decay. Because the threshold density changes with the persistence time, for each persistence time we use a range of host densities that is scaled to the threshold, ranging from 0.8× the threshold to 200× the threshold (the panel for 100 days goes to 300×, so that we can see the full range of infection rates). Woods and Elkinton (1987) observed gypsy moth epidemics at host densities ranging from 3–150 larvae/m2 (0.48 to 2.2 on the log10 scale of the graphs), and so only the graph based on our 2008 estimate (2.56 days, fig. 4C) is centered on the correct range. For longer persistence times, as for our 2007 data (fig. 4B) or for the comparison plot with persistence time of 100 days (fig. 4A), the infection rate is too high at the lower range, while for the shorter persistence time of the Webb et al. data (fig. 4D), it is too low at the higher range. Our estimate of the disease-density threshold thus again appears to be reasonably accurate, suggesting that the disease-density threshold is a useful summary statistic for understanding epidemics in gypsy-moth populations.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the model that includes burnout and pupation (“Burnout+pupation”), equations (1)–(4) with zero transmission after 56 days, to the burnout approximation (“Burnout only”), equation (12), and a version of equations (1)–(4) in which again transmission is zero after 56 days, but for which decay μ = 0 (“Pupation only”).

To assess the usefulness of the burnout approximation, we consider how it compares to the predictions of the realistic model, which includes both pupation and burnout. For a persistence time of 100 days, viral decay is low enough that the realistic model is closest to the pupation-only model, for which μ ≡ 0, and very far from the burnout approximation (fig. 4A). For any shorter persistence time, as in the estimates based on our data or the Webb et al. (1999) data, the pupation-only model predicts higher infection rates than the burnout-plus-pupation model or the burnout approximation. For our best estimate of persistence, from the 2008 data, the realistic model closely approaches the burnout approximation for densities above about 10 larvae/m2, but it is well below the burnout approximation for lower densities (fig. 4C). The burnout approximation is therefore reasonably accurate for more than half the realistic range, but it is quite different from the realistic model at lower densities, suggesting that both pupation and burnout play a role. In particular, pupation is probably part of the reason why epidemics have only been detected at densities considerably higher than the threshold. The lack of observations of epidemics at lower densities may therefore be additional evidence that pupation limits epidemics.

Long-term Dynamics

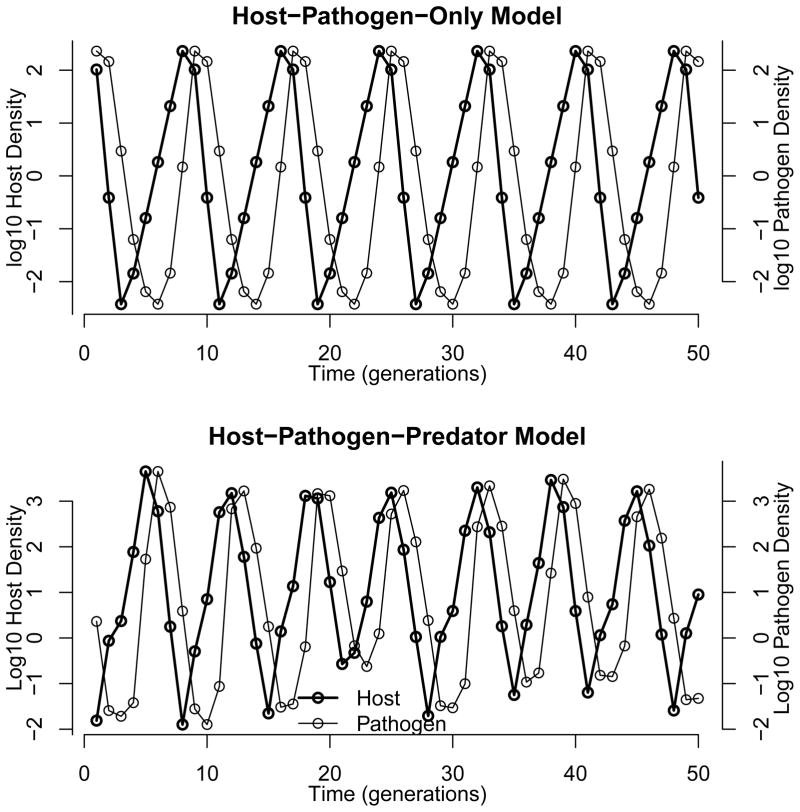

Fig. 5 shows trajectories for the long-term model, including the host-pathogen-only model that excludes the generalist predator, and the host-pathogen-predator model. Both models show cycles that qualitatively match cycles in nature, which typically show a period of 5–10 years, and an amplitude of 3–5 orders of magnitude (Elkinton and Liebhold 1990; Johnson et al. 2005). In the host-pathogen-predator model, the generalist predator interacts with stochasticity to create variability in outbreak timing and intensity (Dwyer et al. 2004).

Figure 5.

Trajectories of the long-term model, equations (9)–(10). Here the estimate of the decay rate is μ = 0.39 from our 2008 data, and the over-winter impact parameter φ = 15, well within the 95% confidence interval for this parameter. Also, we assume that the epidemic lasts two months (56 days) after the infected neonates have died. For the host-pathogen-only model, we set predation a = 0. For the host-pathogen-only model, the remaining parameters are taken from Dwyer et al. (2000): reproductive rate λ = 5.5 and heterogeneity C = 0.86. For the host-pathogen-predator model, the remaining parameters are taken from Dwyer et al. (2004): λ= 74.6, a = 0.967, C = 0.97, b = 0.14 larvae/m2.

To see the effects of persistence on outbreak severity, we consider a wider range of persistence times, using the amplitude of fluctuations as a measure of outbreak severity. For realistic values of long-term survival γ, modest changes have only slight effects, so we ran the model for wide ranges of μ and φ, while considering only γ = 0.01, an upper limit based on Podgwaite et al. (1979)’s data, and γ = 0. We then iterated the models for 200 generations, long enough to eliminate transients, and we calculated the amplitude of fluctuations of host density for the last 100 generations. We defined the amplitude to be the difference between the host population density at a local maximum, and the density at the minimum before the next maximum, with all densities calculated on a log10 scale. For the host-pathogen-predator model, initial conditions can have strong effects, and so for that model we averaged across initial conditions by drawing initial values of host and pathogen densities from uniform distributions that spanned the range of values encompassed by the attractor of each model. We then calculated the average amplitude across 10 realizations. Using data from Murray and Elkinton (1989), we calculated a point estimate and 95% confidence interval on over-winter survival φ, and we used the confidence interval to bound φ (median 7.14, 95% confidence interval 3.53–23.42, see Appendix). To bound within-season decay μ, we used both our 2007 and 2008 estimates and the estimate from the Webb et al. (2001) data.

Fig. 6 then shows that increasing values of over-winter impact φ dramatically increase amplitudes for both models, as expected, while within-season persistence time 1/μ has more complicated effects. For the host-pathogen-only model, increasing persistence time leads to larger amplitudes, but the effect is much stronger as survival time increases beyond 15 days (about 1.2 on the log10 scale of our plot). Indeed, for sufficiently high survival times, the amplitude of fluctuations is so large that the cycles are unbounded. The effect of within-season survival is thus counter-intuitive, because the model shows that more rapid breakdown of virus on foliage makes cycle amplitudes smaller. Smaller-amplitude cycles in turn dampen outbreaks, reducing the chance that the virus will go extinct, and reducing the need for high values of long-term survival γ. For the host-pathogen-predator model, the effect of persistence is similar except that the cycles are never unbounded. Also, for very long persistence times, the cycles are captured by the low-density equilibrium imposed by the generalist predator, leading to smaller-amplitude fluctuations.

Figure 6.

Effects of virus persistence parameters on outbreak severity. Other parameters are as in fig. 5. Shading indicates amplitudes of fluctuations, such that the darkest represents an amplitude of zero, and the lightest represents an amplitude of 7 orders of magnitude. The upper two plots are for the host-pathogen-only model, and the lower two plots are for the host-pathogen-predator model. For the two panels on the left, the environmental survival parameter γ = 0, while for the two on the right, γ = 0:01. The error bars on the points represent the 95% confidence interval on φ in the vertical direction, calculated from Murray and Elkinton (1989), and on persistence time 1/μ in the horizontal direction, with data sources for μ as labeled. For the host-pathogen-only model, periods greater than 6 generally lead to unstable oscillations, in which the virus goes extinct, but for the host-pathogen-predator model the virus always persists.

Cycles in our models occur when the pathogen has a strong impact on the host for at least one year after the host population has fallen below its peak. Increasing over-winter impact φ therefore leads to larger-amplitude fluctuations because increasing φ increases the severity of the epidemic in the year following the peak (Dwyer et al. 2000). Reducing the decay rate μ also increases the severity of the epidemic in the year following the peak, because as fig. 4 shows, reducing μ leads to more severe epidemics at low host densities. The effect of the decay rate μ on epidemics is thus translated into strong effects on long-term dynamics.

In both models, survival of virus from the previous generation, as estimated by the parameter φ, appears to be sufficient to prevent the extinction of the virus even if longer-term survival γ = 0. In the more realistic host-pathogen-predator model in particular, the virus persists for the entire range of values of over-winter impact φ and within-season survival μ. We therefore argue that covert infections and soil reservoirs may not be necessary to explain pathogen-driven outbreaks in the gypsy moth, and perhaps in other outbreaking insects as well. This is not to say that covert infections and soil reservoirs never play a role in the dynamics of baculoviruses, but instead that we may not need to invoke them to explain virus persistence.

Discussion

Our best estimate of the persistence time of the gypsy moth baculovirus is less than 3 days. For this value, the burnout approximation is quite accurate over much of the range of densities at which epidemics have been observed, but it is not very accurate at lower densities. The absence of epidemics at lower densities in nature therefore appears to be due to epidemics being curtailed by pupation, and so it seems likely that in general baculovirus epidemics in gypsy moths are limited by both burnout and pupation. We nevertheless argue that the burnout approximation is useful, first because it is quite accurate at the higher range of observed densities. Also, long-term models that make use of the burnout approximation have qualitatively similar behavior to the more realistic models that we present here. In particular, long-term models that use the burnout approximation also show long-period cycles, and for such models the cycle amplitude also increases sharply with increasing over-winter pathogen impact φ and declines modestly with increasing environmental survival γ (Dwyer et al. 2004; Bjornstad et al. 2010). Long-term models that make use of the burnout approximation are therefore qualitatively useful, especially because they can be understood more easily (Dwyer et al. 2000).

The prediction of the host-density threshold is also quite useful. We expect that epidemics in nature will occur at host densities higher than our best estimate of 0.61 larvae/m2, and indeed epidemics are typically observed at densities above 3 larvae/m2 (Woods et al. 1991; Woods and Elkinton 1987). An interesting feature of this prediction, however, is that it suggests that insecticidal sprays may be used to begin epizootics in gypsy-moth populations at densities that are well below outbreak densities (Elkinton and Liebhold 1990). More generally, our experimental procedure may be useful in the further development of the virus as a management tool (Reardon et al. 1996). One of the obstacles to the development and use of viral sprays is the large-scale field trials necessary to evaluate transmission efficacy of different candidate strains (Thorpe et al. 1999; Reardon et al. 1996). Small-scale transmission experiments might reduce the cost of these evaluations, by providing a preliminary screening of virus strains. It is important to emphasize, however, that using ground-up cadavers instead of purified virus is unlikely to be a viable strategy in biological control, because of regulations about the content of sprays (Hunter-Fujita et al. 1998).

Because the virus in our long-term models survives indefinitely even if we allow only for persistence of virus from the previous generation, we argue that covert infections and soil reservoirs may not be needed to explain baculovirus dynamics. As we have described, however, evidence for covert infections in the lab is stronger for at least a few other insects (Burden et al. 2003, 2006; Kouassi et al. 2009; Vilaplana et al. 2010) than it is for the gypsy moth (Myers et al. 2000; Ilyinykh et al. 2004), and so this conclusion may not be general. An additional caveat is that our models assume that spatial structure plays little role. For gypsy moths in North America, this may not be a bad assumption, because regional weather patterns synchronize populations over large spatial areas (Peltonen et al. 2002), and allowing for regional weather leads to realistic levels of synchrony in spatial versions of our models (Abbott and Dwyer 2008). Nevertheless, in 2001–2003, the third author observed a post-outbreak gypsy moth population that persisted at a high density over a small area, within which virus transmission continued for three larval seasons after the regional population had crashed (G. Dwyer, unpublished). A deeper understanding of long-term persistence may therefore require field studies of the importance of spatial structure in populations at very low densities.

Nothing about our single-epidemic model is specific to the gypsy moth-baculovirus interaction, to the extent that similar models are used to describe epidemics of human diseases (Keeling and Rohani 2007). More concretely, work in the third authors’ lab (G. Dwyer et al., unpublished) has shown that the epidemic model provides an excellent fit to data on baculovirus epidemics in the Douglas-fir tussock moth (Shepherd et al. 1984; Otvos et al. 1987), the western tent caterpillar (Beisner and Myers 1999), and the Balsam-fir sawfly (Moreau et al. 2005). It therefore seems likely that baculovirus epidemics in other outbreaking insects are also limited by pupation. The long-term models are similarly not specific to the gypsy moth, in that most outbreaking insects have discrete generations and transmission in larvae only (Hunter 1991; Dwyer et al. 2004), as assumed by the models. We therefore argue that egg-mass contamination and environmental survival are likely to be sufficient to explain virus persistence in other insects as well.

A general conclusion of our work is thus that, when data are collected in the laboratory or under other artificial conditions, the resulting conclusions may not apply to transmission in nature (Dwyer et al. 2005). The significantly higher decay rate of purified virus (Table 3) emphasizes this point. A corollary is that estimation of model parameters from field data can provide useful insights into host-pathogen dynamics, suggesting that a focus on particular host-pathogen systems can complement the more general models that are typical of most studies in theoretical ecology. Indeed, tests of theory necessarily require system-specific experiments, and we therefore believe that our work usefully illustrates the tension between generality and specificity in population biology.

Interest in the effects of environmental persistence on host-pathogen dynamics has been driven by efforts to understand human diseases such as cholera (Pascual et al. 2002; King et al. 2008) and pandemic influenza (Breban et al. 2009). Recent work has similarly shown that the environmental persistence of Metschnikowia pathogens of Daphnia plays an important role in the dynamics of Metschnikowia-Daphnia interactions (Hall et al. 2005; Duffy and Sivars-Becker 2007; Duffy et al. 2010; Hall et al. 2010). Studies of the environmental persistence of baculoviruses in contrast have a long history (Jaques 1967; Doane 1969), but a lack of estimates of persistence times has hindered our understanding of how baculovirus persistence affects baculovirus dynamics. We therefore hope to have shown that quantifying persistence times can lead to a deeper understanding of disease spread.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Best-fit values of the parameters of the logit-decay model, equation (A8), as fit to data from Jaques (1967, 1972).

| Data set | β0 | β1 | Decay rate μ | Avg. survival, d | Variance infl’n. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaques ’67 | −10.4 | 1.62 | 0.516 | 1.94 | 488 |

| Jaques ’72, ’68 data | −4.88 | 1.13 | 0.731 | 1.37 | 3.10 |

| Jaques ’72, ’69 data | −8.04 | 1.37 | 0.984 | 1.02 | 8.87 |

| Jaques ’72, ’71 data | −1.73 | 0.391 | 1.34 | 0.746 | 5.08 |

Acknowledgments

Emma Fuller was supported by a Research Experiences for Undergraduates fellowship, through the National Science Foundation (NSF). Bret Elderd and Greg Dwyer were supported by NSF grants to Greg Dwyer. Alison Hunter provided useful comments on the manuscript, as did two anonymous reviewers. This is contribution number 1599 of the Kellogg Biological Station.

Contributor Information

Emma Fuller, 1101 E. 57th St., Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA.

Bret D. Elderd, Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA

Greg Dwyer, 1101 E. 57th St., Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA.

References

- Abbott KC, Dwyer G. Using mechanistic models to understand synchrony in forest insect populations: The North American gypsy moth as a case study. The American Naturalist. 2008;172:613–624. doi: 10.1086/591679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa P, Krischik VA. Influence of alkaloids on the feeding preference of eastern deciduous forest trees by the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar. The American Naturalist. 1987;130:53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Beisner B, Myers J. Population density and transmission of virus in experimental populations of the western tent caterpillar (Lepidoptera : Lasiocampidae) Environmental Entomology. 1999;28:1107–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Berger J, Liseo B, Wolpert R. Integrated likelihood methods for eliminating nuisance parameters. Statistical Science. 1999;14:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Biever K, Hostetter D. Field persistence of Trichoplusia-ni (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) single-embedded nuclear polyhedrosis virus on cabbage foliage. Environmental Entomology. 1985;14:579–581. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornstad ON, Robinet C, Liebhold AM. Geographic variation in North American gypsy moth cycles: subharmonics, generalist predators, and spatial coupling. Ecology. 2010;91:106–118. doi: 10.1890/08-1246.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsall M, Sait S, Hails R. Invasion and dynamics of covert infection strategies in structured insect-pathogen populations. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2005;74:464–474. [Google Scholar]

- Boots M, Greenman J, Ross D, Norman R, Hails R, Sait S. The population dynamical implications of covert infections in host-microparasite interactions. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2003;72:1064–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Breban R, Drake JM, Stallknecht DE, Rohani P. The role of environmental transmission in recurrent avian influenza epidemics. PLoS Computational Biology. 2009:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome JR, Sikorowski PP, Neel WW. Effect of sunlight on activity of nuclear polyhedrosis virus from Malacosoma disstria. Journal of Economic Entomology. 1974;67:135–136. [Google Scholar]

- Burden J, Nixon C, Hodgkinson A, Possee R, Sait S, King L, Hails R. Covert infections as a mechanism for long-term persistence of baculoviruses. Ecology Letters. 2003;6:524–531. [Google Scholar]

- Burden J, Possee R, Sait S, King L, Hails R. Phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of persistent baculovirus infections in populations of the cabbage moth (Mamestra brassicae) within the British Isles. Archives of Virology. 2006;151:635–649. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0657-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. 2 Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Capinera JL, Kirouac SP, Barbosa P. Phagodeterrency of cadaver components to gypsy moth larvae, Lymantria dispar. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1976;28:277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Cory JS, Myers JH. The ecology and evolution of insect baculoviruses. Annual Review of Ecological and Evolutionary Systems. 2003;34:239–272. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico V, Elkinton J, Podgwaite J, Buonaccorsi J, Dwyer G. Pathogen clumping: an explanation for non-linear transmission of an insect virus. Ecological Entomology. 2005;30:383–390. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico V, Elkinton JS. Rainfall effects on transmission of gypsy moth (Lepidoptera, Lymantriidae) nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Environmental Entomology. 1995;24:1144–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Doane C. Trans-ovum transmission of a nuclear-polyhedrosis virus in gypsy moth and inducement of virus susceptibility. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1969;14:199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Doane C. Primary pathogens and their role in development of an epizootic in gypsy moth. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1970;15:21. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson A, Meagher M. The population dynamics of brucellosis in the Yellowstone National Park. Ecology. 1996;77:1026–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MA, Caceres CE, Hall SR, Tessier AJ, Ives AR. Temporal, spatial, and between-host comparisons of patterns of parasitism in lake zooplankton. Ecology. 2010;91:3322–3331. doi: 10.1890/09-1611.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MA, Sivars-Becker L. Rapid evolution and ecological host-parasite dynamics. Ecology Letters. 2007;10:44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer G. The effects of density, stage and spatial heterogeneity on the transmission of an insect virus. Ecology. 1991;72:559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer G, Dushoff J, Elkinton JS, Levin SA. Pathogen-driven outbreaks in forest defoliators revisted: Building models from experimental data. The American Naturalist. 2000;156:105–120. doi: 10.1086/303379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer G, Dushoff J, Yee S. The combined effects of pathogens and predators on insect outbreaks. Nature. 2004;430:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature02569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer G, Elkinton JS. Using simple models to predict virus epizootics in gypsy moth populations. The Journal of Animal Ecology. 1993;62:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer G, Elkinton JS, Buonaccorsi JP. Host heterogeneity in susceptibility and disease dynamics: Tests of a mathematical model. The American Naturalist. 1997;150:685–707. doi: 10.1086/286089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer G, Firestone J, Stevens TE. Should models of disease dynamics in herbivorous insects include the effects of varatiability in host-plant foliage quality? The American Naturalist. 2005;165:16–31. doi: 10.1086/426603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D, Rainey P, Embley TM, Scholz D. Development, Life Cycle, Ultrastructure and Phylogenetic Position of Pasteuria ramosa Metchnikoff 1888: Rediscovery of an Obligate Endoparasite of Daphnia magna Straus. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society Biological Sciences. 1996;351:1689–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman Hall/CRC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Elderd BD, Dushoff J, Dwyer G. Host-pathogen interactions, insect outbreaks, and natural selection for disease resistance. The American Naturalist. 2008;172:829–842. doi: 10.1086/592403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkinton JS, Liebhold AM. Population dynamics of gypsy moth in North America. Annual Review of Entomology. 1990;35:571–596. [Google Scholar]

- Elnagar S, Abul-Nasr S. Effect of direct sunlight on the virulence of NPV (nuclear polyhedrosis-virus) of the cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis (boisd) Zeitschrift für angewandte entomologie - Journal of Applied Entomology. 1980;90:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle PF, Adams PHW. Prolonged retention of infectivity in nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Gilpinia hercyniae (Hymenoptera, Diprionidae) on foliage of spruce species. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 1977;29:392–394. [Google Scholar]

- Fuxa JR, Richter AR. Effect of nucleopolyhedrovirus concentration in soil on viral transport to cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) plants. Biocontrol. 2007;52:821–843. [Google Scholar]

- Georgievska L, De Vries RSM, Gao P, Sun X, Cory JS, Vlak JM, Van Der Werf W. Transmission of wild-type and recombinant HaSNPV among larvae of Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on cotton. Environmental Entomology. 2010;39:459–467. doi: 10.1603/EN09183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulson D, Hails R, Williams T, Hirst M, Vasconcelos S, Green B, Carty T, Cory J. Transmission dynamics of a virus in a stage-structued insect population. Ecology. 1995;76:392–401. [Google Scholar]

- Grove MJ, Hoover K. Intrastadial developmental resistance of third instar gypsy moths (Lymantria dispar L.) to L. dispar nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biological Control. 2007;40:355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Hails R, Hernandez-Crespo P, Sait S, Donnelly C, Green B, Cory J. Transmission patterns of natural and recombinant baculoviruses. ECOLOGY. 2002;83:906–916. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SR, Becker CR, Duffy MA, Caceres CE. Variation in resource acquisition and use among host clones creates key epidemiological trade-Offs. American Naturalist. 2010;176:557–565. doi: 10.1086/656523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SR, Duffy MA, Tessier AJ, Caceres CE. Spatial heterogeneity of daphniid parasitism within lakes. Oecologia. 2005;143:635– 644. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg ME. The potential role of pathogens in biological-control. Nature. 1989;337:262–265. doi: 10.1038/337262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A. Traits that distinguish outbreaking and nonoutbreaking macrolepidoptera feeding on northern hardwood trees. Oikos. 1991;60:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter-Fujita F, Entwistle P, Evans H, Crook N. Insect viruses and pest management. Wiley and Sons; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ignoffo CM, Hostetter DL, Sikorowski PP, Sutter G, Brooks WM. Inactivation of representative species of entomopathogenic viruses, a bacterium, fungus, and protozoan by an UV light-source. Environmental Entomology. 1977;6:411–415. [Google Scholar]

- Il’inykh A, Ul’yanova E. Latency of baculoviruses. Biology Bulletin. 2005;32:496–502. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyinykh A, Shternshis M, Kuzminov S. Exploration into a mechanism of transgenerational transmission of nucleopolyhedrovirus in Lymantria dispar L. in Western Siberia. Biocontrol. 2004;49:441–454. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques RP. Persistence of a nuclear polyhedrosis virus in habitat of host insect Trichoplusia ni I. Polyhedra deposited on foliage. Canadian Entomologist. 1967;99:785. [Google Scholar]

- Jaques RP. Inactivation of nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Trichoplusia ni by gamma and ultraviolet radiation. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 1968;14:1161. doi: 10.1139/m68-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaques RP. Inactivation of foliar deposits of virus of Trichoplusia ni (Lepidoptera:Noctuidae) and Pieris rapae (Lepidoptera:Pieridae) and tests on protectant additives. Canadian Entomologist. 1972;104:1985–1994. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Liebhold AM, Bjrnstad ON. Circumpolar variation in periodicity and synchrony among gypsy moth populations. Journal of Animal Ecology. 2005;74:882–892. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling MJ, Rohani P. Modeling Infectious Diseases in Humans and Animals. Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kermack WO, McKendrick AG. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 1927;53:33–55. doi: 10.1007/BF02464423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AA, Ionides EL, Pascual M, Bouma MJ. Inapparent infections and cholera dynamics. Nature. 2008;454:877–881. doi: 10.1038/nature07084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouassi LN, Tsuda K, Goto C, Mukawa S, Sakamaki Y, Kusigemati K, Nakamura M. Prevalence of latent virus in Spodoptera litura (Fabricius) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and its activation by a heterologous virus. Applied Entomology and Zoology. 2009;44:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman N, Corning B, Coiro M. The effects of intracage ventilation on microenvironmental conditions in filter-top cages. Laboratory animals. 1992;26:206–210. doi: 10.1258/002367792780740503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]