Abstract

The commonest association of thymic stromal deficiency resulting in T-cell immunodeficiency is the DiGeorge syndrome (DGS). This results from abnormal development of the third and fourth pharyngeal arches and is most commonly associated with a microdeletion at chromosome 22q11 though other genetic and non-genetic causes have been described. The immunological competence of affected individuals is highly variable, ranging from normal to a severe combined immunodeficiency when there is complete athymia. In the most severe group, correction of the immunodeficiency can be achieved using thymus allografts which can support thymopoiesis even in the absence of donor-recipient matching at the major histocompatibility loci. This review focuses on the causes of DGS, the immunological features of the disorder, and the approaches to correction of the immunodeficiency including the use of thymus transplantation.

Keywords: DiGeorge syndrome, immunodeficiency, thymus transplantation, 22q11 deletion, T-cell development

Introduction

DiGeorge syndrome (DGS) was first described in the 1960’s and classically comprises T-cell deficiency (due to thymic hypoplasia), hypoparathyroidism, cardiac malformations, and facial abnormalities. Subsequently, it was recognized that deletions of the long arm of chromosome 22 at position q.11 were most commonly associated with DGS (1, 2). DGS is also found associated with other genetic abnormalities and with certain teratogenic influences. It was also recognized that multiple other clinical features could be associated with this deletion. The DGS phenotype is very heterogenous with variable expression of the different features including the immunodeficiency.

Causes of DGS

Early thymic development

At an early stage of embryonic development the pharyngeal apparatus can be recognized. This becomes segmented into a series of pharyngeal arches and pouches each comprising an outer ectodermal and inner endodermal layer separated by mesodermal tissue and neural crest cells (NCC) (3, 4). The thymus, parathyroid glands and great vessels of the heart develop from these structures notably the third and fourth arch structures. Thymic epithelial development is under the control of the transcription factor, FoxN1, and studies of expression of this factor have demonstrated that the thymus derives from an area of the endoderm in the ventral aspect of the third pouch (5). The mesoderm and NCC contribute to the thymic connective tissue including vascular endothelium and mesenchymal cells, the latter thought to be important in regulating early thymic epithelial development (6). Parathyroid gland development is closely allied, this organ being derived from the endoderm of the ventral part of the third pharyngeal pouch again with mesodermal cells and NCC contributing the connective tissue and vascular endothelium. From the eighth week of human gestation, bone marrow derived T-cell precursors have been shown to enter the thymic structure (7). The further development of the thymus is dependent on two-way interactions between these lymphoid cells and the thymic stroma (8, 9).

Hematopoietic cell defects resulting in severe combined immunodeficiencies lead to failure or disturbed thymic development as a consequence of failure of this lymphoid – stromal interaction (10, 11) which can be reversed by successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (12). These aspects of thymic stromal deficiency are considered elsewhere in this Research Topic.

The classical features of DGS occur as a result of the early embryonic disturbance of development of the pharyngeal arch apparatus and are independent of the influence of hematopoietic cell precursors on thymic development.

Genetic associations of DGS

DiGeorge syndrome overlaps considerably with velocardiofacial (VCF) syndrome and to a lesser extent with conotruncal anomaly face syndrome; all these are associated with hemizygous 22q.11 deletions manifesting with a wide array of clinical features (13). The deletion is also associated with neurodevelopmental delay, behavioral, and psychiatric features. The multitude of possible clinical features (over 180) have been reviewed by Shprintzen (14). DGS and VCF are sometimes collectively referred to as the 22q.11 deletion syndrome. The incidence of this deletion is high at around 1:4000 (15). In 90–95% of cases this arises de novo with the other 5–10% being inherited from an affected parent (13). Over 90% of cases have a typical 3 Mb deletion including over 30 different genes (16). This seems to occur between two regions with homologous low copy repeats suggesting that deletion occurs through a process of homologous recombination. Most other patients have a smaller, 1.5 Mb, deletion (17, 18). There is no correlation between the size of the deletion and the clinical phenotype. Discordance between phenotypes has been described in monozygotic twins carrying the deletion (19). In rare cases mutations in a single gene, TBX1, have been described resulting in the DGS phenotype (20, 21). TBX1 is one of the T-box genes with an important role in regulating the expression of transcription factors (22). Studies of a mouse model with a syngenic deletion on chromosome 16 have helped elucidate the role of Tbx1. Homozygous deletions of this gene result in a very severe, lethal phenotype including all the features of DGS whilst hemizygous loss of the gene produces a milder phenotype with variable penetrance of the different clinical features (23). However, implicating TBX1 as the sole gene causing DGS in 22q deletion syndromes may not be the whole story. Adjacent deletions not involving TBX1 can give a phenotype with some overlapping features (24) as can atypical deletions covering different critical regions in the same part of the chromosome (25). Other genes in the region, also affected in the typical DGS deletion, may have a modifying effect on expression of the disorder. These include CRKL, coding for an adaptor protein involved in growth factor signaling. Crkl is expressed in neural crest derived tissues and in mice null for the gene there is aberrant or absent thymic development (26). However, hemizygous Crkl loss is not associated with an abnormal clinical phenotype suggesting a gene dosing effect. The effect of compound heterozygosity for Tbx1 and Crkl deletions, on development of DGS features, is additive (27). The function of TBX1 is complex and mediated through regulation of downstream transcription factors. The detailed role of TBX1 in 22q.11 deletion syndromes and in thymus development in particular has been reviewed by others (28, 29).

A much rarer but well characterized genetic association with a DGS phenotype occurs with interstitial deletions at chromosome 10p (30–33). This has been designated DGS 2.The clinical phenotype overlaps with that associated with 22q.11 deletion but with some important differences. Sensorineural hearing loss and mental retardation are relatively common features in those with 10p deletions but rare in 22q11 deletion cases; renal anomalies, and general growth retardation are more prevalent in 10p deletion than in 22q11 deletion cases (34). Deletions at 10p syndrome have been estimated as having an incidence of 1 in 200,000, some 50 times less common than 22q.11 deletions (35, 36). The role of the genes deleted and responsible for the clinical picture is less well understood than in 22q deletion DGS but on-going work has identified some critical regions involved in developmental abnormalities (32, 37).

Mutations in the Chromodomain Helicase DNA-binding protein 7 (CHD7) gene are responsible for most cases of Colobomata, Heart defect, Atresia choanae, Retarded growth and development, Genital hypoplasia, Ear anomalies/deafness (CHARGE) syndrome. A DGS phenotype including complete athymia may be part of this syndrome but there is marked variability in expression of the multiple clinical features. The incidence has been estimated at 1 in 8500 (38). CHD7 acts as a regulator of transcription of other genes. Its expression has been demonstrated in the NCC of the pharyngeal arches. Normal development of these structures has been shown to be dependent on the co-expression of Chd7 and Tbx1 in mice suggesting the likely mechanism by which CHARGE syndrome can lead to a DGS phenotype (39, 40).

Non-genetic associations of DGS

Embryopathy induced by exposure of the fetus to retinoic acid can include a DGS phenotype (41). Retinoic acid affects Tbx1 expression in avian embryos (42) whilst it has also been shown that Tbx1 can, in at least some circumstances, regulate retinoic acid metabolism (43). Fetal alcohol syndrome (44–46) and maternal diabetes (47, 48) have also been associated with the DGS phenotype. In the latter, there is often an associated renal agenesis. It has been postulated that maternal diabetes can lead to interference with neural crest and mesenchymal cell migration (49).

Immunological Features of DGS

Incidence and severity

DiGeorge syndrome may be associated with a complete range of T-cell deficiency from normal T-cell numbers and function to complete DGS (cDGS) with a T-negative severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-like picture. It was recognized early on that the T-cell immunodeficiency may be incomplete and the term partial DGS (pDGS) was coined (50). In a large series of patients with 22q11 deletions, the proportion of affected individuals falling into the cDGS category was around 1.5% of the 218 who underwent immunological testing or around 0.5% of the whole series of over 550 patients (13). A much higher proportion had minor laboratory abnormalities suggesting pDGS. In one series, from a major referral center, mild-moderate lymphopenia, consistent with pDGS, was reported in 30% of 22q.11 patients (51).

Less is known of the frequency of severe immunodeficiency in 10p deletion DGS. A review of published cases identified low levels of T cells and immunoglobulins as well as a small or hypoplastic thymus in 9 of 32 (28%) patients evaluated. However none of these patients were reported as having significant infections, suggesting that the immunodeficiency was likely partial rather than complete (34).

In CHARGE syndrome, severe immunodeficiency has been described (51–55). The proportion of cases affected with immunodeficiency is not well established as there is no reported large series looking at immunological parameters. Immunodeficiency may not always be considered in CHARGE; one recent report of a large series of 280 cases did not provide any information on the prevalence of recurrent infections or immunodeficiency (56). In a series of 25 cases (51), 16 (60%) were found to have lymphopenia. Only nine had full immunophenotyping performed and two of these had a picture of cDGS. A further five of eight patients dying in infancy had marked lymphopenia but did not have lymphocyte phenotyping performed so it is possible that the incidence of cDGS was higher. The authors do however concede that this series of patients referred to a specialist center might present a biased view. Nevertheless, the proportion of children with CHARGE syndrome affected by a significant immunodeficiency is probably at least as high as the proportion in DGS associated with 22q deletion. This conclusion would be consistent with the report of a series of 54 cases of patients referred for thymus transplantation for cDGS where the numbers of CHARGE and of 22q deleted cases were roughly in proportion to the incidences of the two genetic defects (55).

Immunodeficiency in partial DGS

The majority of children with thymic insufficiency as part of DGS, whatever the underlying cause, will have only a partial form of immunodeficiency. The consequences are an increased susceptibility to infections and sometimes immunodysregulation resulting in autoimmunity. A wide range of T-cell immunity is seen in pDGS from near normal to near completely deficient. Normal or near normal T-cell numbers can be found even in those with an apparently absent or hypoplastic thymus and in these it is probable that some thymic tissue is ectopically placed (57). There may be a small subset of more severely deficient 22q.11 – pDGS patients with T-cell numbers near the lower end of the range who have an increased susceptibility to “T-cell” type pathogens such as Candida albicans and viral infections and an increased non-cardiac mortality (58, 59). Hypocalcemia was an associated feature of this subgroup in one of these studies (58) and was also associated with lymphopenia in another study of CHARGE patients (51). Otherwise there is no correlation between the severity of immunodeficiency and the clinical phenotype in regard the other features of DGS (60). Most pDGS patients do not suffer opportunistic or life-threatening infections. Their infections tend to be of a sinopulmonary nature, more consistent with a humoral than a T-cell immunodeficiency. Susceptibly to such respiratory tract infections is likely to be at least partly due to non-immunological issues such as velo-pharyngeal insufficiency, eustachian tube dysfunction, disco-ordinate swallowing, gastro-esophageal reflux, and sometimes tracheo-bronchomalacia (59, 61).

As is the case with other partial T-cell deficient states, autoimmune disease can occur in pDGS. This has most commonly been reported as manifesting with immune cytopenias, arthritis, or hyper/hypothyroidism (62–73). The mechanism by which tolerance breaks down leading to autoimmunity in pDGS is not clear. Many forms of primary immunodeficiency are associated with an increased risk of autoimmune disease including conditions not associated with dysregulation of T cells. It has been suggested that persistent antigen stimulation from frequent and/or persistent infections may predispose to autoimmunity (74). However, in pDGS autoimmunity is not predominantly found in those with the most severe or frequent infections (65, 75). It is more likely that disturbance of central or peripheral tolerance or both occur as a consequence of the thymic abnormality. In the normal situation, central tolerance is generated through the presentation of tissue specific peptides to developing thymocytes by medullary thymic epithelial cells in the context of autologous major histocompatibility antigens and under the regulation of the autoimmune regulator (AIRE). There is subsequent deletion (negative selection) of thymocytes recognizing these self-antigens. It is possible that a reduced bulk of thymic tissue in pDGS results in incomplete negative selection or that AIRE expression in pDGS is reduced or otherwise abnormal. The author is not aware of any reported studies of AIRE expression in thymic tissue from pDGS cases. Abnormalities of thymic tissue, including AIRE expression, has been described in SCID due to recombination activating gene (RAG) defects and may contribute to the multisystem inflammation/autoimmunity seen in Omenn syndrome (76) though these patients also have a defect of regulatory T cells suggesting a possible peripheral tolerance defect in addition (77). In pDGS, negative selection must occur in relation to most antigens since the autoimmune disease seen is usually limited to one or two organs or systems. By contrast, in autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1 (APS-1) (78) caused by mutations in the AIRE gene, multiple autoimmune disorders are typical. Breakdown of peripheral tolerance is another possible explanation for autoimmunity in pDGS. One study reported reduced numbers of circulating CD4+ Foxp3+ T cells, described as natural T regulatory cells (nTregs) in pDGS patients compared to controls. The levels of these cells correlated closely with the numbers of recent thymic emigrant cells suggesting they were at least partially thymus derived (75). Another study (79) looked at CD4+ CD25+ cells which include Treg cells. In both studies these populations were present in reduced numbers in pDGS patients compared to controls at all ages but there was no difference between the levels in patients with and without autoimmunity. Immunological assessment of pDGS patients often shows low overall numbers of T cells compared to normal with a tendency to improve after the first year of life, although in 10p deletion syndrome a progressive T-cell lymphopenia has been reported (33). Mitogen responsiveness is generally normal in pDGS (80, 81). An increase in T-cell numbers with age may in part be due to the development of oligoclonal expansions resulting in abnormal T-cell receptor spectratypes. (75, 82–85). Naïve T-cell proportions are lower than normal and fall off more quickly with age than in an age – matched control group (82). T-cell recombination excision circles (TRECs) were found to correlate well with the proportions of circulating naïve T cells (86), though a cautionary note was struck by the report of a patient, with what turned out to be pDGS, showing very low TREC levels with good naïve cell proportions (87).

Humoral immune defects and disturbance of B-cell immunity were recognized very early on after DGS was first described (50). These may be relevant to the types of infections suffered. A number of relatively small series have looked at immunoglobulin and antibody levels in DGS associated with 22q.11 deletion (62, 63, 65, 68, 75, 88–90) and CHARGE syndrome (51). Low immunoglobulin levels were reported with variable frequency, most commonly affecting IgM but also occasionally causing a sufficiently low IgG to merit immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Defective antibody responses to polysaccharide antigens were reported in a significant minority of patients. A recently published, much larger study reported on over 1000 patients, with a median age of 3 years, from the European Society for Immunodeficiency and US Immunodeficiency Network (91). Forty two percent were recorded as having 22q.11 deletion but the underlying cause was not reported in the remainder. Overall, 2.7% were on immunoglobulin replacement therapy (3% in those over 3 years old). In the over 3 years age group 6.2% had IgG levels below 5 g/l. Amongst patients over 3 years of age, around 0.7% had complete and 1% partial IgA deficiency whilst 23% had low levels of IgM. There was no association between low immunoglobulin levels, in any of the isotypes, and T-cell counts nor between low T-cell counts and immunoglobulin levels. The authors acknowledged that the data were incomplete and that there may have been some reporting bias in that these patients were registered through immunodeficiency networks. Nevertheless, this study provides the best estimate of the prevalence of humoral immune deficit in DGS. B-cell numbers were not reported in this study but in another study were found to be generally normal though sometimes low in the first year of life, normalizing later (92). The repertoire of IgH usage is also normal but further diversification through somatic hypermutation is deficient (93). It has also been shown that the maturation of B-cells toward a memory phenotype is impaired in pDGS (88). Given the specific role of the thymus in T- but not B-cell development it is probable, but not proven, that B-cell abnormalities are secondary to the T-cell deficiency in these patients.

Immunodeficiency in complete DGS

Complete DGS is associated with athymia and results in a picture of SCID in a patient showing other variable features of DGS. Affected patients suffer opportunistic infections and, like other infants with SCID, are likely to die early unless they can be treated with a corrective procedure. In addition to susceptibility to infections these patients are at risk from transfusion acquired graft versus host disease (55).

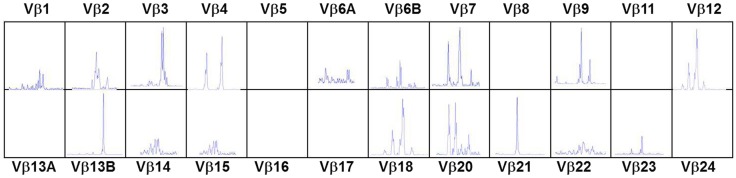

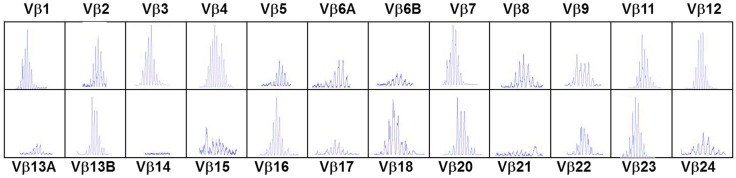

In the typical form of cDGS the T-cell numbers are <50/cumm and mitogen responses are absent. B cells are usually present in normal numbers and NK cells in normal or high numbers. In a proportion of cases there may be some mature T cells present either through maternal engraftment (94) or through oligoclonal expansion of memory phenotype T cells which have developed without thymic processing (95). In the latter case, as in SCID these cells can mediate severe inflammation leading to an Omenn-like picture with erythrodermic rashes, enteropathy, and lymphadenopathy (53, 96) This is called atypical cDGS. The diagnosis of complete athymia then depends on showing absence (<50/cumm) of T cells with a naïve (CD3 + CD45 RA+CD62L+) phenotype as well as abnormal T-cell receptor usage either by T-cell receptor spectratyping or FACS analysis of usage of V Beta TCR chains (96). An example of the abnormal spectratype in an atypical cDGS patient is shown in Figure 1 which can be compared to the normal spectratype achieved in the same patient after successful thymus transplantation (Figure 2). Mitogen responsiveness is usually, but not invariably, impaired in these atypical patients (96).

Figure 1.

T-cell receptor spectratyping of 24 Vβ families obtained using polymerase chain reaction amplification across the VDJ region and then plotting according to the size of the PCR products. Patient with atypical cDGS showing very abnormal spectratype with several completely missing families and abnormal skewed distribution in other families.

Figure 2.

T-cell receptor spectratyping performed as in legend to Figure 1. Same patient as in Figure 1, 23 months after thymus transplantation. Much more normal spectratype. All families represented mostly with Gaussian distribution.

Diagnosis of cDGS depends on the findings of the clinical features of DGS together with the above immunological findings with or without identification of one of the associated genetic abnormalities. A recent report (97) describes two patients with absent T cells and DGS associated with 22q.11 deletion who were also found to have pathogenic mutations in the DCLRE1C (Artemis) gene, a classical cause of SCID. A clue to the latter diagnosis was the virtual absence of B cells as well as T cells which is very unusual in cDGS alone.

Newborn screening for SCID using TREC detection on blood spots has been in place in certain states of USA for around 3 years (98, 99). Since TRECs will be absent or extremely low (86) this allows the early diagnosis of cDGS. In the California program (98) screening of nearly one million newborns picked up one cDGS case who went on to thymus transplantation, eight with T-cell lymphopenia associated with 22q.11 deletion and one with CHARGE association. Picking up the latter group was useful in the early identification of these children as having significant immunodeficiency and allowed infection prevention measures to be put in place including avoidance of live viral vaccinations. Newborn screening programs should offer the opportunity of a better outcome through earlier intervention in both cDGS and some cases of pDGS.

Corrective Treatment for cDGS

Hematopoietic cell transplantation

Treatment with hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for athymia is dependent on the transfer of mature post-thymic T cells. Long term survival after such transplants has been reported (100, 101) though at a low rate (41–48%) compared to survival after HCT for SCID (102). Survival in the subgroup receiving matched sibling donor transplants was better at over 60% (100). Mortality was related to other features of DGS, to graft versus host disease and to pre-existing viral infections. The quality of immune reconstitution achieved, as expected, is poor with no evidence of naïve T cells and often low CD4 counts with skewed distribution of T-cell receptor usage. However immunoglobulin production and antibody responses were relatively good. Though overall the outcome after HCT for cDGS is not good, in some circumstances, such as overwhelming viral infection, HCT from a matched sibling may be life-saving (103).

Thymus transplantation

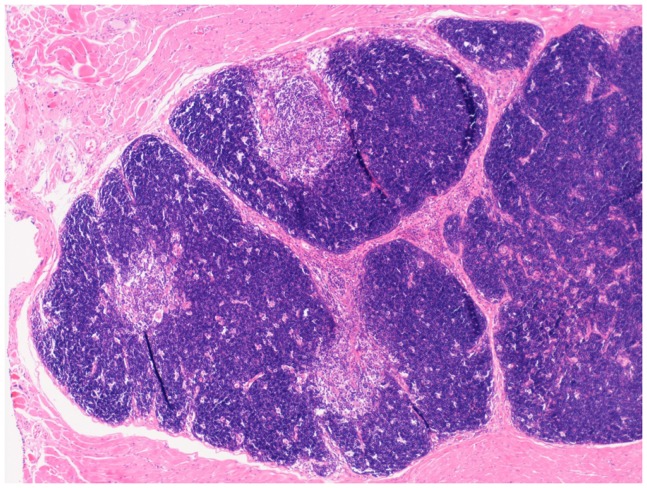

Replacement of thymic function using allografted tissue was first achieved using human fetal thymic tissue (104, 105). The use of post natal human thymus, necessarily removed at the time of cardiac surgery in infants undergoing median sternotomy, was pioneered by Markert at Duke University (106, 107) and has become established as the treatment of choice for cDGS. More recently this approach has also been used in London using an almost identical approach (manuscript in preparation). The thymus is cultured for 12–21 days prior to transplantation into the quadriceps muscle of the patient. During this period most thymocytes are washed out or undergo apoptosis whilst the thymic stroma is preserved. Patients with atypical cDGS are pre-treated with anti thymocyte globulin and continuing cyclosporine A (108) whilst typical cases receive no pre-conditioning. The results have been published (55, 109) and of 60 patients treated 43 survived (72%). This compares favorably with the outcome after HCT described above though strict comparison is not possible as the thymus transplant patients were a selected group. After successful transplantation, patients develop host derived naïve T cells with a normal T-cell receptor repertoire (Figure 2), normal mitogen responses and antigen specific immune responses restricted to the host major histocompatibility complex (MHC). There is normalization of the TCR repertoire in circulating regulatory T cells (110). Biopsies of transplanted thymus taken from 2 months onward show thymopoiesis (111) and normal thymus architecture (Figure 3). The levels of circulating T cells achieved do not usually match normal age matched controls and are more akin to the levels seen in children with pDGS. Tolerance to the donor’s MHC has been demonstrated (112) and this has been exploited to enable parathyroid transplantation from a parent in situations where there is coincidental partial MHC class 2 matching between the donor and the parent (113).

Figure 3.

Low-power view of a biopsy of transplanted thymus stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. Normal looking thymic tissue surrounded by striated muscle. There is good corticomedullary distinction.

Deaths after thymus transplantation were related mainly to pre-existing co-morbidities, mostly chronic lung disease and systemic viral infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) (114). This virus is a particular problem. Screening of potential thymic donors always excludes CMV positive donors but a proportion of cDGS patients will have acquired the virus before thymus transplantation. Biopsies of transplanted thymus tissue from two patients with CMV in the Markert series showed no evidence of thymopoiesis even though the epithelium was viable (111). Both patients died. A similar appearance was found in a CMV infected patient in London who also died without evidence of thymopoiesis (manuscript in preparation). The mechanism by which CMV interferes with thymopoiesis is not clear but as a result of this experience, CMV infection should be considered at least a relative contraindication to thymus transplantation. After successful thymus transplantation patients are able to control infections and to come off antibiotic prophylaxis and immunoglobulin therapy with normal responses to immunization. The main problem that has been encountered is the development of autoimmunity. Around one third of patients have shown autoimmunity, mainly hypothyroidism but also with a significant number of immune cytopenias (109). It is interesting that this spectrum of autoimmunity is similar to that seen in pDGS patients, as discussed above, and may have the same causation or may be related to faulty thymic education related to the fact that the transplanted thymic epithelial cells are not MHC matched, as discussed below. No clinical or methodological correlates with risk of autoimmune development could be identified in the Duke University series. (114).

The success of transplantation of thymus which is not matched at the MHC loci offers interesting insights into thymocyte development. In particular, it suggests that positive and negative selection of developing thymocytes can occur in the absence of self MHC expressed on thymic epithelial cells. The mechanism by which this takes place is incompletely understood. Reconstitution experiments in nude mice with MHC incompatible thymic tissue showed that functional T cell development could be supported by haematopoeitic cell-expressed MHC instead of TEC- expressed MHC (115). Further work showed that development of functional CD4 (but not CD8) cells however does seem to require interaction with MHC on TECs but not any particular allelic form of MHC (116). Under the influence of AIRE expressed on thymic epithelium dendritic cells have been shown to have a role in negative selection in mice (117). Whilst negative selection may be imperfect resulting in autoimmunity in some cases, it must be largely effective since multiple system/organ autoimmunity from widespread lack of central tolerance has not been seen. Positive selection has also been shown to be mediated by fibroblasts (118) and by thymocytes (119, 120). Influx of these cell types expressing host MHC to the developing thymus allograft could therefore have the potential for mediating the selection processes.

Conclusion

Study of the thymic deficiency in DGS provides insights into the development of the thymus and the mechanisms of thymopoiesis required to generate a robust and diverse T-cell mediated immunity. Thymus transplantation offers a novel way of correcting the immunodeficiency in this disorder.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.de la Chapelle A, Herva R, Koivisto M, Aula P. A deletion in chromosome 22 can cause DiGeorge syndrome. Hum Genet (1981) 57(3):253–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley RI, Zackai EH, Emanuel BS, Kistenmacher M, Greenberg F, Punnett HH. The association of the DiGeorge anomalad with partial monosomy of chromosome 22. J Pediatr (1982) 101(2):197–200 10.1016/S0022-3476(82)80116-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham A. The development and evolution of the pharyngeal arches. J Anat (2001) 199(Pt 1–2):133–41 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19910133.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham A, Smith A. Patterning the pharyngeal arches. Bioessays (2001) 23(1):54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackburn CC, Manley NR. Developing a new paradigm for thymus organogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol (2004) 4(4):278–89 10.1038/nri1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Lievre CS, Le Douarin NM. Mesenchymal derivatives of the neural crest: analysis of chimaeric quail and chick embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol (1975) 34(1):125–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haynes BF, Heinly CS. Early human T cell development: analysis of the human thymus at the time of initial entry of hematopoietic stem cells into the fetal thymic microenvironment. J Exp Med (1995) 181(4):1445–58 10.1084/jem.181.4.1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klug DB, Carter C, Gimenez-Conti IB, Richie ER. Cutting edge: thymocyte-independent and thymocyte-dependent phases of epithelial patterning in the fetal thymus. J Immunol (2002) 169(6):2842–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson G, Jenkinson EJ. Lymphostromal interactions in thymic development and function. Nat Rev Immunol (2001) 1(1):31–40 10.1038/35095500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill J, Malin M, Sutherland J, Gray D, Hollander G, Boyd R. Thymic generation and regeneration. Immunol Rev (2003) 195:28–50 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2003.00077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poliani PL, Facchetti F, Ravanini M, Gennery AR, Villa A, Roifman CM, et al. Early defects in human T-cell development severely affect distribution and maturation of thymic stromal cells: possible implications for the pathophysiology of Omenn syndrome. Blood (2009) 114(1):105–8 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller SM, Kohn T, Schulz AS, Debatin KM, Friedrich W. Similar pattern of thymic-dependent T-cell reconstitution in infants with severe combined immunodeficiency after human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical and HLA-nonidentical stem cell transplantation. Blood (2000) 96(13):4344–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan AK, Goodship JA, Wilson DI, Philip N, Levy A, Seidel H, et al. Spectrum of clinical features associated with interstitial chromosome 22q11 deletions: a European collaborative study. J Med Genet (1997) 34(10):798–804 10.1136/jmg.34.10.798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shprintzen RJ. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome: 30 Years of study. Dev Disabil Res Rev (2008) 14(1):3–10 10.1002/ddrr.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tezenas Du MS, Mendizabai H, Ayme S, Levy A, Philip N. Prevalence of 22q11 microdeletion. J Med Genet (1996) 33(8):719. 10.1136/jmg.33.8.719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson C, Sirotkin H, Pandita R, Goldberg R, McKie J, Wadey R, et al. Molecular definition of 22q11 deletions in 151 velo-cardio-facial syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet (1997) 61(3):620–9 10.1086/515508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meechan DW, Maynard TM, Gopalakrishna D, Wu Y, LaMantia AS. When half is not enough: gene expression and dosage in the 22q11 deletion syndrome. Gene Expr (2007) 13(6):299–310 10.3727/000000006781510697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edelmann L, Pandita RK, Morrow BE. Low-copy repeats mediate the common 3-Mb deletion in patients with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Hum Genet (1999) 64(4):1076–86 10.1086/302343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodship J, Cross I, Scambler P, Burn J. Monozygotic twins with chromosome 22q11 deletion and discordant phenotype. J Med Genet (1995) 32(9):746–8 10.1136/jmg.32.9.746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yagi H, Furutani Y, Hamada H, Sasaki T, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, et al. Role of TBX1 in human del22q11.2 syndrome. Lancet (2003) 362(9393):1366–73 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14632-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zweier C, Sticht H, Aydin-Yaylagul I, Campbell CE, Rauch A. Human TBX1 missense mutations cause gain of function resulting in the same phenotype as 22q11.2 deletions. Am J Hum Genet (2007) 80(3):510–7 10.1086/511993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith J. T-box genes: what they do and how they do it. Trends Genet (1999) 15(4):154–8 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01693-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jerome LA, Papaioannou VE. DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat Genet (2001) 27(3):286–91 10.1038/85845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rauch A, Zink S, Zweier C, Thiel CT, Koch A, Rauch R, et al. Systematic assessment of atypical deletions reveals genotype-phenotype correlation in 22q11.2. J Med Genet (2005) 42(11):871–6 10.1136/jmg.2004.030619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amati F, Conti E, Novelli A, Bengala M, Diglio MC, Marino B, et al. Atypical deletions suggest five 22q11.2 critical regions related to the DiGeorge/velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet (1999) 7(8):903–9 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guris DL, Fantes J, Tara D, Druker BJ, Imamoto A. Mice lacking the homologue of the human 22q11.2 gene CRKL phenocopy neurocristopathies of DiGeorge syndrome. Nat Genet (2001) 27(3):293–8 10.1038/85855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guris DL, Duester G, Papaioannou VE, Imamoto A. Dose-dependent interaction of Tbx1 and Crkl and locally aberrant RA signaling in a model of del22q11 syndrome. Dev Cell (2006) 10(1):81–92 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollander G, Gill J, Zuklys S, Iwanami N, Liu C, Takahama Y. Cellular and molecular events during early thymus development. Immunol Rev (2006) 209:28–46 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00357.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papangeli I, Scambler P. The 22q11 deletion: DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes and the role of TBX1. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol (2013) 2(3):393–403 10.1002/wdev.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elstner CL, Carey JC, Livingston G, Moeschler J, Lubinsky M. Further delineation of the 10p deletion syndrome. Pediatrics (1984) 73(5):670–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger R, Larroche JC, Toubas PL. Deletion of the short arm of chromosome No. 10. Acta Paediatr Scand (1977) 66(5):659–62 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1977.tb07965.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daw SC, Taylor C, Kraman M, Call K, Mao J, Schuffenhauer S, et al. A common region of 10p deleted in DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes. Nat Genet (1996) 13(4):458–60 10.1038/ng0896-458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pignata C, D’Agostino A, Finelli P, Fiore M, Scotese I, Cosentini E, et al. Progressive deficiencies in blood T cells associated with a 10p12-13 interstitial deletion. Clin Immunol Immunopathol (1996) 80(1):9–15 10.1006/clin.1996.0088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van EH, Groenen P, Fryns JP, Van de Ven W, Devriendt K. The phenotypic spectrum of the 10p deletion syndrome versus the classical DiGeorge syndrome. Genet Couns (1999) 10(1):59–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berend SA, Spikes AS, Kashork CD, Wu JM, Daw SC, Scambler PJ, et al. Dual-probe fluorescence in situ hybridization assay for detecting deletions associated with VCFS/DiGeorge syndrome I and DiGeorge syndrome II loci. Am J Med Genet (2000) 91(4):313–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartsch O, Wagner A, Hinkel GK, Lichtner P, Murken J, Schuffenhauer S. No evidence for chromosomal microdeletions at the second DiGeorge syndrome locus on 10p near D10S585. Am J Med Genet (1999) 83(5):425–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindstrand A, Malmgren H, Verri A, Benetti E, Eriksson M, Nordgren A, et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of patients with overlapping 10p deletions. Am J Med Genet A (2010) 152A(5):1233–43 10.1002/ajmg.a.33366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Issekutz KA, Graham JM, Jr., Prasad C, Smith IM, Blake KD. An epidemiological analysis of CHARGE syndrome: preliminary results from a Canadian study. Am J Med Genet A (2005) 133A(3):309–17 10.1002/ajmg.a.30560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aramaki M, Kimura T, Udaka T, Kosaki R, Mitsuhashi T, Okada Y, et al. Embryonic expression profile of chicken CHD7, the ortholog of the causative gene for CHARGE syndrome. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol (2007) 79(1):50–7 10.1002/bdra.20330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanlaville D, Etchevers HC, Gonzales M, Martinovic J, Clement-Ziza M, Delezoide AL, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of CHARGE syndrome in fetuses with CHD7 truncating mutations correlates with expression during human development. J Med Genet (2006) 43(3):211–7 10.1136/jmg.2005.036160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coberly S, Lammer E, Alashari M. Retinoic acid embryopathy: case report and review of literature. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med (1996) 16(5):823–36 10.3109/15513819609169308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts C, Ivins SM, James CT, Scambler PJ. Retinoic acid down-regulates Tbx1 expression in vivo and in vitro. Dev Dyn (2005) 232(4):928–38 10.1002/dvdy.20268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braunstein EM, Monks DC, Aggarwal VS, Arnold JS, Morrow BE. Tbx1 and Brn4 regulate retinoic acid metabolic genes during cochlear morphogenesis. BMC Dev Biol (2009) 9:31. 10.1186/1471-213X-9-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ammann AJ, Wara DW, Cowan MJ, Barrett DJ, Stiehm ER. The DiGeorge syndrome and the fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Dis Child (1982) 136(10):906–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cavdar AO. DiGeorge’s syndrome and fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Dis Child (1983) 137(8):806–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sulik KK, Johnston MC, Daft PA, Russell WE, Dehart DB. Fetal alcohol syndrome and DiGeorge anomaly: critical ethanol exposure periods for craniofacial malformations as illustrated in an animal model. Am J Med Genet Suppl (1986) 2:97–112 10.1002/ajmg.1320250614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novak RW, Robinson HB. Coincident DiGeorge anomaly and renal agenesis and its relation to maternal diabetes. Am J Med Genet (1994) 50(4):311–2 10.1002/ajmg.1320500402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gosseye S, Golaire MC, Verellen G, Van LM, Claus D. Association of bilateral renal agenesis and DiGeorge syndrome in an infant of a diabetic mother. Helv Paediatr Acta (1982) 37(5):471–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Digilio MC, Marino B, Formigari R, Giannotti A. Maternal diabetes causing DiGeorge anomaly and renal agenesis. Am J Med Genet (1995) 55(4):513–4 10.1002/ajmg.1320550427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lischner HW, DiGeorge AM. Role of the thymus in humoral immunity. Lancet (1969) 2(7629):1044–9 10.1016/S0140-6736(69)90647-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jyonouchi S, McDonald-McGinn DM, Bale S, Zackai EH, Sullivan KE. CHARGE (coloboma, heart defect, atresia choanae, retarded growth and development, genital hypoplasia, ear anomalies/deafness) syndrome and chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a comparison of immunologic and nonimmunologic phenotypic features. Pediatrics (2009) 123(5):e871–7 10.1542/peds.2008-3400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chopra C, Baretto R, Duddridge M, Browning MJ. T-cell immunodeficiency in CHARGE syndrome. Acta Paediatr (2009) 98(2):408–10 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gennery AR, Slatter MA, Rice J, Hoefsloot LH, Barge D, McLean-Tooke A, et al. Mutations in CHD7 in patients with CHARGE syndrome cause T-B + natural killer cell + severe combined immune deficiency and may cause Omenn-like syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol (2008) 153(1):75–80 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03681.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Writzl K, Cale CM, Pierce CM, Wilson LC, Hennekam RC. Immunological abnormalities in CHARGE syndrome. Eur J Med Genet (2007) 50(5):338–45 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Markert ML, Devlin BH, Alexieff MJ, Li J, McCarthy EA, Gupton SE, et al. Review of 54 patients with complete DiGeorge anomaly enrolled in protocols for thymus transplantation: outcome of 44 consecutive transplants. Blood (2007) 109(10):4539–47 10.1182/blood-2006-10-048652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bergman JE, Janssen N, Hoefsloot LH, Jongmans MC, Hofstra RM, Van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM. CHD7 mutations and CHARGE syndrome: the clinical implications of an expanding phenotype. J Med Genet (2011) 48(5):334–42 10.1136/jmg.2010.087106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shah SS, Lai SY, Ruchelli E, Kazahaya K, Mahboubi S. Retropharyngeal aberrant thymus. Pediatrics (2001) 108(5):E94. 10.1542/peds.108.5.e94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herwadkar A, Gennery AR, Moran AS, Haeney MR, Arkwright PD. Association between hypoparathyroidism and defective T cell immunity in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. J Clin Pathol (2010) 63(2):151–5 10.1136/jcp.2009.072074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eberle P, Berger C, Junge S, Dougoud S, Buchel EV, Riegel M, et al. Persistent low thymic activity and non-cardiac mortality in children with chromosome 22q11.2 microdeletion and partial DiGeorge syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol (2009) 155(2):189–98 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03809.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sullivan KE, Jawad AF, Randall P, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, McDonald-McGinn DM, et al. Lack of correlation between impaired T cell production, immunodeficiency, and other phenotypic features in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes. Clin Immunol Immunopathol (1998) 86(2):141–6 10.1006/clin.1997.4463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kobrynski LJ, Sullivan KE. Velocardiofacial syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome: the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndromes. Lancet (2007) 370(9596):1443–52 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61601-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jawad AF, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai E, Sullivan KE. Immunologic features of chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). J Pediatr (2001) 139(5):715–23 10.1067/mpd.2001.118534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith CA, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Sullivan KE. Increased prevalence of immunoglobulin a deficiency in patients with the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). Clin Diagn Lab Immunol (1998) 5(3):415–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown JJ, Datta V, Browning MJ, Swift PG. Graves’ disease in DiGeorge syndrome: patient report with a review of endocrine autoimmunity associated with 22q11.2 deletion. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab (2004) 17(11):1575–9 10.1515/JPEM.2004.17.11.1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gennery AR, Barge D, O’Sullivan JJ, Flood TJ, Abinun M, Cant AJ. Antibody deficiency and autoimmunity in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Arch Dis Child (2002) 86(6):422–5 10.1136/adc.86.6.422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rasmussen SA, Williams CA, Ayoub EM, Sleasman JW, Gray BA, Bent-Williams A, et al. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in velo-cardio-facial syndrome: coincidence or unusual complication? Am J Med Genet (1996) 64(4):546–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verloes A, Curry C, Jamar M, Herens C, O’Lague P, Marks J, et al. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and del(22q11) syndrome: a non-random association. J Med Genet (1998) 35(11):943–7 10.1136/jmg.35.11.943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davies K, Stiehm ER, Woo P, Murray KJ. Juvenile idiopathic polyarticular arthritis and IgA deficiency in the 22q11 deletion syndrome. J Rheumatol (2001) 28(10):2326–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sullivan KE, McDonald-McGinn DM, Driscoll DA, Zmijewski CM, Ellabban AS, Reed L, et al. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-like polyarthritis in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge anomalad/velocardiofacial syndrome/conotruncal anomaly face syndrome). Arthritis Rheum (1997) 40(3):430–6 10.1002/art.1780400307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.DePiero AD, Lourie EM, Berman BW, Robin NH, Zinn AB, Hostoffer RW. Recurrent immune cytopenias in two patients with DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome. J Pediatr (1997) 131(3):484–6 10.1016/S0022-3476(97)80085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kratz CP, Niehues T, Lyding S, Heusch A, Janssen G, Gobel U. Evans syndrome in a patient with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Hematol Oncol (2003) 20(2):167–72 10.1080/0880010390158685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sakamoto O, Imaizumi M, Suzuki A, Sato A, Tanaka T, Ogawa E, et al. Refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a patient with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Pediatr Int (2004) 46(5):612–4 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.01940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davies JK, Telfer P, Cavenagh JD, Foot N, Neat M. Autoimmune cytopenias in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Clin Lab Haematol (2003) 25(3):195–7 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2003.00508.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev (2003) 2(6):364–9 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00052-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McLean-Tooke A, Barge D, Spickett GP, Gennery AR. Immunologic defects in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2008) 122(2):362–7 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cavadini P, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Fontana S, Nagafuchi S, Mazzolari E, et al. AIRE deficiency in thymus of 2 patients with Omenn syndrome. J Clin Invest (2005) 115(3):728–32 10.1172/JCI23087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cassani B, Poliani PL, Moratto D, Sobacchi C, Marrella V, Imperatori L, et al. Defect of regulatory T cells in patients with Omenn syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2010) 125(1):209–16 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perniola R, Lobreglio G, Rosatelli MC, Pitotti E, Accogli E, De RC. Immunophenotypic characterisation of peripheral blood lymphocytes in autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1: clinical study and review of the literature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab (2005) 18(2):155–64 10.1515/JPEM.2005.18.2.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sullivan KE, McDonald-McGinn D, Zackai EH. CD4(+) CD25(+) T-cell production in healthy humans and in patients with thymic hypoplasia. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol (2002) 9(5):1129–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chinen J, Rosenblatt HM, Smith EO, Shearer WT, Noroski LM. Long-term assessment of T-cell populations in DiGeorge syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2003) 111(3):573–9 10.1067/mai.2003.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sullivan KE, McDonald-McGinn D, Driscoll DA, Emanuel BS, Zackai EH, Jawad AF. Longitudinal analysis of lymphocyte function and numbers in the first year of life in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). Clin Diagn Lab Immunol (1999) 6(6):906–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Piliero LM, Sanford AN, McDonald-McGinn DM, Zackai EH, Sullivan KE. T-cell homeostasis in humans with thymic hypoplasia due to chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Blood (2004) 103(3):1020–5 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cancrini C, Romiti ML, Finocchi A, Di CS, Ciaffi P, Capponi C, et al. Post-natal ontogenesis of the T-cell receptor CD4 and CD8 Vbeta repertoire and immune function in children with DiGeorge syndrome. J Clin Immunol (2005) 25(3):265–74 10.1007/s10875-005-4085-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pierdominici M, Mazzetta F, Caprini E, Marziali M, Digilio MC, Marino B, et al. Biased T-cell receptor repertoires in patients with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). Clin Exp Immunol (2003) 132(2):323–31 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02134.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McLean-Tooke A, Barge D, Spickett GP, Gennery AR. Flow cytometric analysis of TCR Vbeta repertoire in patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Scand J Immunol (2011) 73(6):577–85 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lima K, Abrahamsen TG, Foelling I, Natvig S, Ryder LP, Olaussen RW. Low thymic output in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome measured by CCR9+CD45RA+ T cell counts and T cell receptor rearrangement excision circles. Clin Exp Immunol (2010) 161(1):98–107 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04152.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Knutsen AP, Baker MW, Markert ML. Interpreting low T-cell receptor excision circles in newborns with DiGeorge anomaly: importance of assessing naive T-cell markers. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2011) 128(6):1375–6 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Finocchi A, Di CS, Romiti ML, Capponi C, Rossi P, Carsetti R, et al. Humoral immune responses and CD27+ B cells in children with DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion syndrome). Pediatr Allergy Immunol (2006) 17(5):382–8 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kung SJ, Gripp KW, Stephan MJ, Fairchok MP, McGeady SJ. Selective IgM deficiency and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2007) 99(1):87–92 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60627-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schubert MS, Moss RB. Selective polysaccharide antibody deficiency in familial DiGeorge syndrome. Ann Allergy (1992) 69(3):231–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patel K, Akhter J, Kobrynski L, Benjamin Gathmann MA, Davis O, Sullivan KE. Immunoglobulin deficiencies: the B-lymphocyte side of DiGeorge Syndrome. J Pediatr (2012) 161(5):950–3 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Junker AK, Driscoll DA. Humoral immunity in DiGeorge syndrome. J Pediatr (1995) 127(2):231–7 10.1016/S0022-3476(95)70300-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Haire RN, Buell RD, Litman RT, Ohta Y, Fu SM, Honjo T, et al. Diversification, not use, of the immunoglobulin VH gene repertoire is restricted in DiGeorge syndrome. J Exp Med (1993) 178(3):825–34 10.1084/jem.178.3.825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ocejo-Vinyals JG, Lozano MJ, Sanchez-Velasco P, Escribano de DJ, Paz-Miguel JE, Leyva-Cobian F. An unusual concurrence of graft versus host disease caused by engraftment of maternal lymphocytes with DiGeorge anomaly. Arch Dis Child (2000) 83(2):165–9 10.1136/adc.83.2.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Collard HR, Boeck A, Mc Laughlin TM, Watson TJ, Schiff SE, Hale LP, et al. Possible extrathymic development of nonfunctional T cells in a patient with complete DiGeorge syndrome. Clin Immunol (1999) 91(2):156–62 10.1006/clim.1999.4691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Markert ML, Alexieff MJ, Li J, Sarzotti M, Ozaki DA, Devlin BH, et al. Complete DiGeorge syndrome: development of rash, lymphadenopathy, and oligoclonal T cells in 5 cases. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2004) 113(4):734–41 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Heimall J, Keller M, Saltzman R, Bunin N, McDonald-McGinn D, Zakai E, et al. Diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and artemis deficiency in two children with T-B-NK+ immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol (2012) 32(5):1141–4 10.1007/s10875-012-9741-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kwan A, Church JA, Cowan MJ, Agarwal R, Kapoor N, Kohn DB, et al. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency and T-cell lymphopenia in California: Results of the first 2 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2013) 132(1):140–50 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Routes JM, Grossman WJ, Verbsky J, Laessig RH, Hoffman GL, Brokopp CD, et al. Statewide newborn screening for severe T-cell lymphopenia. JAMA (2009) 302(22):2465–70 10.1001/jama.2009.1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Janda A, Sedlacek P, Honig M, Friedrich W, Champagne M, Matsumoto T, et al. Multicenter survey on the outcome of transplantation of hematopoietic cells in patients with the complete form of DiGeorge anomaly. Blood (2010) 116(13):2229–36 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.McGhee SA, Lloret MG, Stiehm ER. Immunologic reconstitution in 22q deletion (DiGeorge) syndrome. Immunol Res (2009) 45(1):37–45 10.1007/s12026-009-8108-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gennery AR, Slatter MA, Grandin L, Taupin P, Cant AJ, Veys P, et al. Transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells and long-term survival for primary immunodeficiencies in Europe: entering a new century, do we do better? J Allergy Clin Immunol (2010) 126(3):602–10 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ip W, Zhan H, Gilmour KC, Davies EG, Qasim W. 22q11.2 Deletion syndrome with life-threatening adenovirus infection. J Pediatr (2013) 163(3):908–10 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.August CS, Berkel AI, Levey RH, Rosen FS, Kay HE. Establishment of immunological competence in a child with congenital thymic aplasia by a graft of fetal thymus. Lancet (1970) 1(7656):1080–3 10.1016/S0140-6736(70)92755-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cleveland WW, Fogel BJ, Brown WT, Kay HE. Foetal thymic transplant in a case of DiGeorge’s syndrome. Lancet (1968) 2(7580):1211–4 10.1016/S0140-6736(68)91694-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Markert ML, Kostyu DD, Ward FE, McLaughlin TM, Watson TJ, Buckley RH, et al. Successful formation of a chimeric human thymus allograft following transplantation of cultured postnatal human thymus. J Immunol (1997) 158(2):998–1005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Markert ML, Boeck A, Hale LP, Kloster AL, McLaughlin TM, Batchvarova MN, et al. Transplantation of thymus tissue in complete DiGeorge syndrome. N Engl J Med (1999) 341(16):1180–9 10.1056/NEJM199910143411603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Markert ML, Alexieff MJ, Li J, Sarzotti M, Ozaki DA, Devlin BH, et al. Postnatal thymus transplantation with immunosuppression as treatment for DiGeorge syndrome. Blood (2004) 104(8):2574–81 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Markert ML, Devlin BH, McCarthy EA. Thymus transplantation. Clin Immunol (2010) 135(2):236–46 10.1016/j.clim.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chinn IK, Milner JD, Scheinberg P, Douek DC, Markert ML. Thymus transplantation restores the repertoires of forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3)(+) and FoxP3(-) T cells in complete DiGeorge anomaly. Clin Exp Immunol (2013) 173(1):140–9 10.1111/cei.12088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Markert ML, Li J, Devlin BH, Hoehner JC, Rice HE, Skinner MA, et al. Use of allograft biopsies to assess thymopoiesis after thymus transplantation. J Immunol (2008) 180(9):6354–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chinn IK, Devlin BH, Li YJ, Markert ML. Long-term tolerance to allogeneic thymus transplants in complete DiGeorge anomaly. Clin Immunol (2008) 126(3):277–81 10.1016/j.clim.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chinn IK, Markert ML. Induction of tolerance to parental parathyroid grafts using allogeneic thymus tissue in patients with DiGeorge anomaly. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2011) 127(6):1351–5 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Markert ML, Devlin BH, Chinn IK, McCarthy EA, Li YJ. Factors affecting success of thymus transplantation for complete DiGeorge anomaly. Am J Transplant (2008) 8(8):1729–36 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02301.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zinkernagel RM, Althage A. On the role of thymic epithelial cells vs. bone marrow-derived cells in repertoire selection of T cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci (1999) 96:8092–7 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Martinic MM, van den Broek MF, Rulicke T, Huber C, Odermatt B, Reith W, et al. Functional CD8+ but not CD4+ T cell responses develop independent of thymic epithelial MHC. Proc Nat Acad Sci (2006) 103(39):14435–40 10.1073/pnas.0606707103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liston A, Lesage S, Wilson J, Peltonen L, Goodnow CC. Aire regulates negative selection of organ-specific T cells. Nat Immunol (2003) 4(4):350–4 10.1038/ni906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pawlowski T, Elliott JD, Loh DY, Staerz UD. Positive selection of T lymphocytes on fibroblasts. Nature (1993) 364(6438):642–5 10.1038/364642a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Li W, Kim MG, Gourley TS, McCarthy BP, Sant’Angelo DB, Chang CH. An alternate pathway for CD4 T cell development: thymocyte-expressed MHC class II selects a distinct T cell population. Immunity (2005) 23(4):375–86 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Choi EY, Jung KC, Park HJ, Chung DH, Song JS, Yang SD, et al. Thymocyte-thymocyte interaction for efficient positive selection and maturation of CD4 T cells. Immunity (2005) 23(4):387–96 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]