Abstract

Activating transcription factor-(ATF-) 3, a stress-inducible transcription factor, is rapidly upregulated under various stress conditions and plays an important role in inducing cancer cell apoptosis. NBM-TP-007-GS-002 (GS-002) is a Taiwanese propolin G (PPG) derivative. In this study, we examined the antitumor effects of GS-002 in human hepatoma Hep3B and HepG2 cells in vitro. First, we found that GS-002 significantly inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell apoptosis in dose-dependent manners. Several main apoptotic indicators were found in GS-002-treated cells, such as the cleaved forms of caspase-3, caspase-9, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). GS-002 also induced endoplasmic reticular (ER) stress as evidenced by increases in ER stress-responsive proteins including glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153), phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), phosphorylated protein endoplasmic-reticular-resident kinase (PERK), and ATF-3. The induction of ATF-3 expression was mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in GS-002-treated cells. Furthermore, we found that GS-002 induced more cell apoptosis in ATF-3-overexpressing cells. These results suggest that the induction of apoptosis by the propolis derivative, GS-002, is partially mediated through ER stress and ATF-3-dependent pathways, and GS-002 has the potential for development as an antitumor drug.

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary malignancy of the liver and accounts for as many as 1 million deaths annually worldwide [1–4]. The major risk factors include chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, environmental carcinogens such as aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), alcoholic cirrhosis, and inherited genetic disorder such as hemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, and tyrosinemia. Among them, HBV, HCV, and AFB1 are responsible for approximately 80% of all HCC cases [4]. Despite rapid expansion of information obtained from researchers, the molecular mechanism of hepatocarcinogenesis and the molecular genetics of HCC remain elusive.

In the past decade, induction of apoptosis has become the major strategy to combat cancer. However, resistance to apoptosis is considered to be a characteristic of several types of cancers. Therefore, a search for innovative strategies other than induction of apoptosis is urgently needed. Recent research demonstrated that the potential to induce apoptosis through endoplasmic reticular (ER) stresses can be a target for cancer therapy. Activating transcription factor-(ATF-) 3 is a member of the ATF/CREB family of basic-region leucine zipper-(bZIP-) type transcription factors [5] and is a highly versatile stress sensor for a wide range of conditions including hypoxia, hyponutrition, oxidative stresses, ER stresses, various genotoxic stresses [6, 7], and inflammatory reactions [8, 9]. ATF-3 is also activated by serum stimulation downstream of c-Myc [10] and is frequently overexpressed in various tumors including those of the prostate [11], breast [12], and Hodgkin's lymphomas [13]. Previous studies reported that ATF-3 was induced by treating cells with antitumorigenic compounds [14–18] and a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor [19]. On the other hand, ATF-3 is rapidly induced in cells treated with growth stimulators such as serum and growth factors [20]. ATF-3 induces DNA synthesis and expression of cyclin D1 in hepatocytes [21] and is involved in serum-induced cell proliferation as a target gene of c-myc [10]. In breast cancer, ATF-3 enhances cancer cell-initiating features [22] and is associated with activation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway [23].

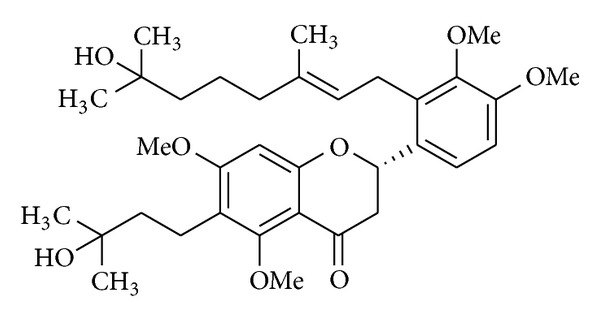

Besides traditional synthetic compounds, many natural products were found to exert anticancer effects. Identification of the active components and their mechanisms of action are important to assess their potential for clinical use and possible diverse side effects. Propolis, a natural resinous product, is collected from various plant sources by honeybees, which use it to seal holes in their honeycombs. Propolis was reported to exhibit a broad spectrum of activities including antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and anticancer properties [24, 25]. Ten propolins (propolins A~J) of the active components were isolated and characterized. Our previous studies suggested that propolin G (PPG) isolated from Taiwanese green propolis induced growth inhibition and apoptosis of brain cancer cells possibly due to modulating expressions of cell cycle-regulator genes and further activating caspase cascades and mitochondrial pathways, ultimately resulting in the induction of apoptosis [26]. We were interested in developing more-potent antitumor activity from PPG and found that the PPG derivative, NBM-TP-007-GS-002 (GS-002) (Figure 1), was a more-potent antitumor drug than was the parental PPG. In this study, we further investigated the molecular mechanism of GS-002 in inhibiting hepatoma cell proliferation.

Figure 1.

Structure of NBM-TP-007-GS-002 (GS-002).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

PPG and its derivative, GS-002 (Figure 1), were synthesized by Professor Huang (Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan), and a stock solution was made in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent. Inhibitors of SP600125, SB203580, and PD98059 were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Antibodies against the cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), Bad, phospho-p38, and p38 and a Cleavage Caspase Antibody Sampler Kit were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Antibodies against c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), phospho-JNK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and phospho-ERK were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). An anti-α-tubulin antibody was purchased from Frontier Laboratories (Chicago, IL), and an anti-ATF-3 antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

2.2. Cell Culture and Cell Viability Assay

Human hepatoma Hep3B and HepG2 cells were purchased from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan) and cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% L-glutamine and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. To determine viable cells, cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 6 × 104 cells/mL. Drug-treated cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and stained with 1% crystal violet dye as described previously [27].

2.3. Flow Cytometric Analysis

Drug-treated cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) alone or double-stained with Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies, Taiwan Brand, Taipei, Taiwan) and PI and were analyzed by FACScan flow cytometry using CellQuest 3.3 analysis software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) as described previously [28].

2.4. DNA Fragmentation Assay

Drug-treated cells were lysed with digestion buffer containing 0.5% sarkosyl, 0.5 mg/mL proteinase K, 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0), and 10 mM EDTA at 56°C for 3 h and then treated with RNase A (0.5 μg/mL) for another 2 h at 56°C. DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl (25 : 24 : 1), analyzed by 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with SYBR Green dye, visualized under UV light, and photographed.

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

Total cellular proteins (40 μg) were resolved by 8%~12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-(SDS-) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence kits (Amersham, Arlington, IL) as described previously [28].

2.6. Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells, and complementary (c)DNA was prepared as previously described [28]. ATF-3 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNAs were amplified by incubating 500 ng equivalents of total cDNA in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (at pH 8.3) containing 500 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.1% gelatin, 200 μM of each dNTP, and 50 units/mL SuperTaq DNA Polymerase (Ambion, Austin, TX) with the following oligonucleotide primers: 5′-GCTGCAAAGTGCCGAAACAAG-3′ and 5′-TCTCCAATGGCTTCAGGGTT-3′ for ATF-3 and 5′-TGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTGGC-3′ and 5′-CATGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC-3′ for GAPDH. Thermal cycle conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 94°C for 5 min; followed by 25 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and with a final cycle at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were analyzed on 1% agarose gels and stained with SYBR Green dye.

2.7. Transient Transfection

The ATF-3 overexpressing plasmid, pCI-ATF3, and ATF-3 promoter reporter plasmid, Luc-1850 (ATF-Luc-1850), were kindly provided by Professor Shigetaka Kitajima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan). The ATF-Luc-1850 reporter plasmid contains an 1850-bp fragment, −1850 to +50 relative to the transcription start site of the human ATF-3 gene. To overexpress ATF-3, cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at the density of 6 × 104 cells/mL and transfected with the pCI-ATF3 plasmid or an empty pcDNA3 plasmid as a control using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Taiwan Brand).

For the ATF-3 reporter activity assay, cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at a density of 6 × 104 cells/mL and transfected with the ATF-Luc-1850 reporter plasmid and phRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI) as an internal control plasmid with Lipofectamine 2000. Total cell lysates were collected, and the luciferase activity was detected using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and a Plate Chameleon Multilabel plate reader (HIDEX OY, Turku, Finland) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Luciferase activities of the reported plasmid were normalized to luciferase activities of the internal control plasmid [29].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) for the indicated number of independently performed experiments. The statistical analysis was performed using one-way Student's t-test, and differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. GS-002 Induced Apoptosis in Human Hepatoma Cells

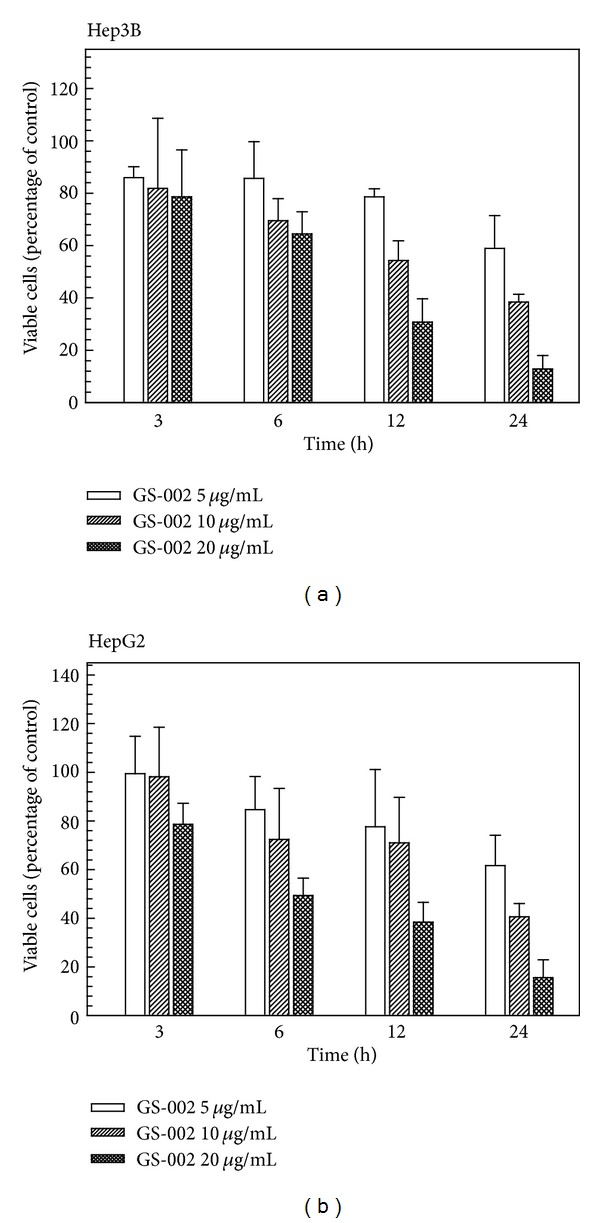

We examined the antitumor effect of GS-002 in human hepatoma cell lines and found that GS-002 significantly inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell apoptosis in dose-dependent manners (Figure 2). In the human hepatoma Hep3B and HepG2 cell lines, GS-002 significantly induced cell death in dose- and time-dependent manners and, respectively, showed 88% and 84% reductions in cell viability with 20 μg/mL of GS-002 at 24 h of treatment.

Figure 2.

The propolis derivative, GS-002, decreased viable cell numbers in human hepatoma cells. (a) Hep3B and (b) HepG2 cells were treated with various concentrations of GS-002 for the indicated time periods, and then viable cell numbers were determined with a crystal violet dye. Values are presented as the mean ± SE of three independent experiments.

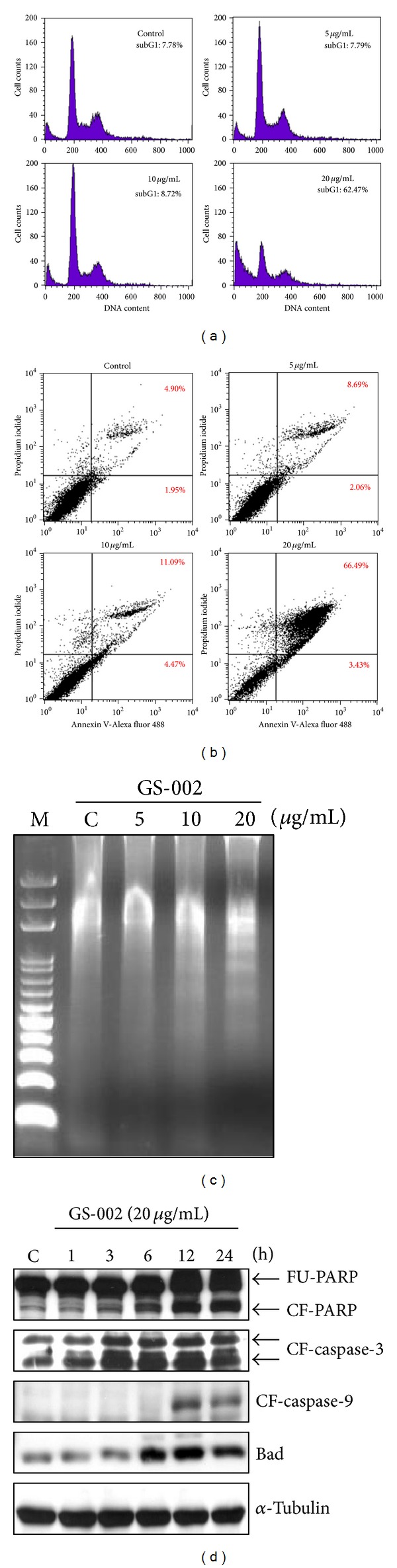

Cell-cycle progression was analyzed by flow cytometry with PI staining. After treatment with GS-002 for 24 h, there was no significant cell-cycle change in the G1, S, or G2/M phases compared to control cells (Figure 3(a)). However, a marked increase in the subG1 apoptotic population was seen in cells treated with 20 μg/mL of GS-002. subG1 populations were 7.78% and 62.47% of control cells and cells treated with 20 μg/mL of GS-002, respectively. Cell death was also characterized using flow cytometry with PI and Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 488 staining of Hep3B cells. The lower right quadrant of the FACS histogram represents early apoptotic cells, which were stained with the green fluorescent Alexa488 dye, and the upper right quadrant of the FACS histogram represents late apoptotic cells, which were stained with both the red-green fluorescence PI and Alexa488 dyes. As shown in Figure 3(b), the late apoptotic cell population increased from 4.90% to 66.49% in cells treated with 20 μg/mL GS-002. We next questioned whether GS-002 induced apoptosis in Hep3B cells. After treatment of Hep3B cells with various concentrations of GS-002 for 24 h, genomic DNA from cells was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA fragmentation ladders significantly increased as shown in Figure 3(c). We next determined the cleavage of PARP and activation of caspases in GS-002-treated cells. After treatment with GS-002 for 24 h, the cleavage of PARP and cleaved (i.e., activated) forms of caspases-3 and -9 and Bad were found in GS-002-treated cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3(d)). These results suggest that GS-002 inhibited cell proliferation through activating an apoptotic pathway in human hepatoma cells.

Figure 3.

The propolis derivative, GS-002, induced cell apoptosis in human hepatoma cells. Hep3B cells were treated with various concentrations of GS-002 for 24 h, and (a) the subG1 population was determined by a flow cytometric analysis; (b) apoptotic cells were determined by a flow cytometric analysis with annexin-V/PI staining; and (c) the DNA fraction was extracted and chromatographed by agarose gel electrophoresis. (d) Hep3B cells were treated with 20 μg/mL of GS-002 for the indicated time periods. Total cell lysates were used to detect the protein expression of full-length PPAR (FU-PPAR), cleaved form of PPAR (CF-PPAR), cleaved form of caspase-3 (CF-caspase-3), cleaved form of caspase-9 (CF-caspase-9), Bad, and α-tubulin by Western blotting.

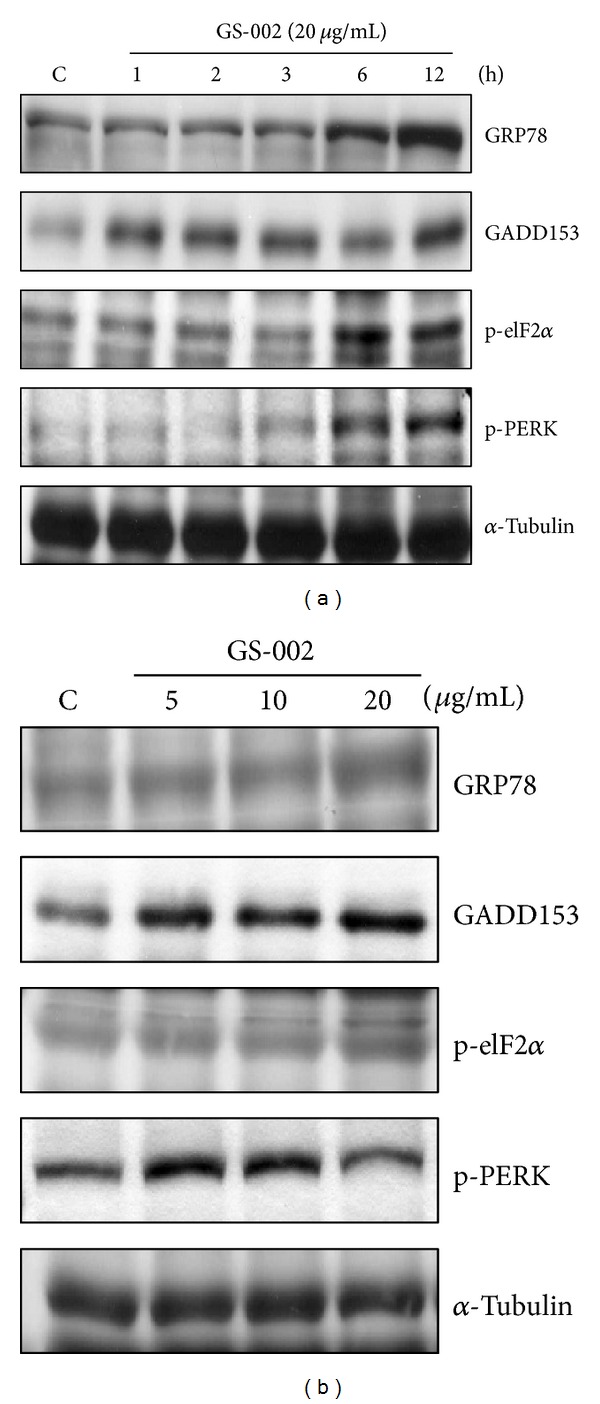

3.2. ER Stress Is Involved in GS-002-Induced Apoptosis

It was suggested that prolonged ER stress can cause cells to undergo apoptosis. To examine whether GS-002 also caused apoptosis through ER stress in human hepatoma cells, several ER-responsive proteins and ER-specific signals were detected. We first measured expressions of GRP78, which acts as a gatekeeper in activating ER stress, and GADD153, a transcription factor increased by ER stress. The Western blot analysis showed that expressions of GRP78 and GADD153 significantly increased after GS-002 treatment in dose- and time-dependent manners (Figure 4). We next detected the phosphorylation of ER-specific signals, including PERK and eIF2α, which are known to be activated in response to accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER lumen. As shown in Figure 4, GS-002 indeed induced the phosphorylation of PERK and its substrate, eIF2α, in dose- and time-dependent manners. The results suggested that GS-002 was able to induce ER stress in Hep3B cells.

Figure 4.

The propolis derivative, GS-002, induced endoplasmic reticular stress in human hepatoma cells. Hep3B cells were treated (a) with 20 μg/mL GS-002 for the indicated time periods or (b) with various concentrations of GS-002 for 12 h. Total cell lysates were used to detect protein expressions of GRP78, GADD153, phospho-eIF2α (p-eIF2α), phosphor-PERK (p-PEK), and α-tubulin by Western blotting.

3.3. GS-002 Induced ATF-3 Expression through MAPK Pathways

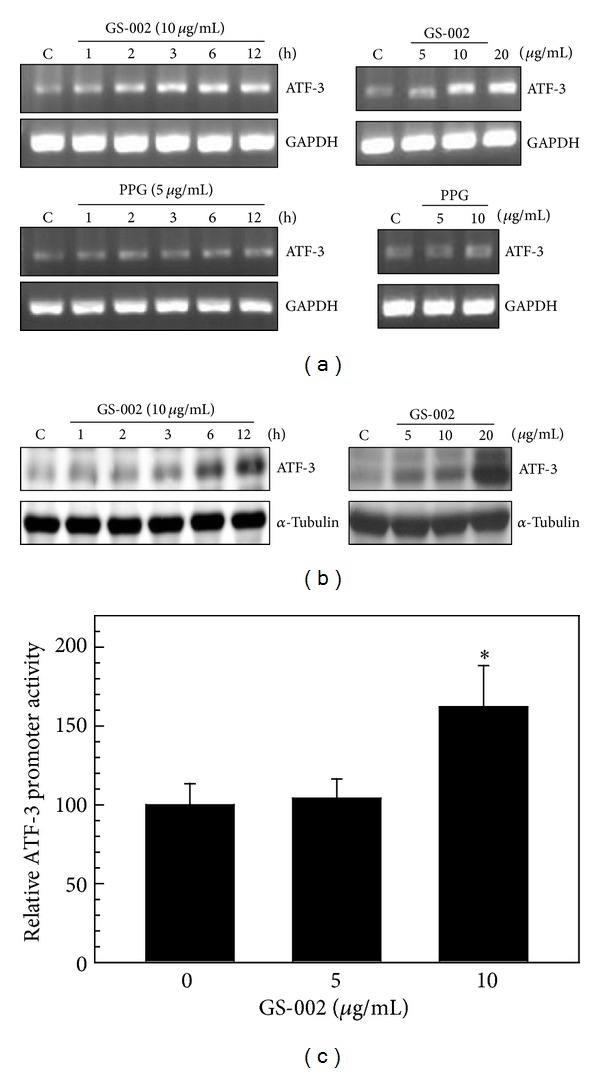

It is known that ATF-3 is also a stress-responsive protein, which can be induced by ER stress [30]. Next, we wanted to understand whether GS-002 can induce ATF-3 expression in human hepatoma cells. Hep3B cells were treated with GS-002, and we found that GS-002 significantly induced ATF-3 messenger (m)RNA expression in dose- and time-dependent manners (Figure 5(a)). ATF-3 protein expression also increased after GS-002 treatment (Figure 5(b)). However, the GS-002 parental compound, PPG, did not induce ATF-3 expression at a concentration of 10 μg/mL (Figure 5(a), bottom). To examine whether GS-002 induced ATF-3 expression at the transcription level, we used the ATF-Luc-1850 reporter plasmid to determine the gene promoter activity of ATF-3. Hep3B cells were transfected with the ATF-Luc-1850 reporter plasmid and phRL-TK (an internal control plasmid) for 24 h and then treated with various concentrations of GS-002 for another 24 h. As for GS-002 exposure, the gene promoter of ATF-3 in Hep3B cells was upregulated in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5(c)). These results suggest that GS-002 was able to induce ATF-3 expression at the transcription level.

Figure 5.

The propolis derivative, GS-002, induced ATF-3 expression in human hepatoma cells. (a) Hep3B cells were treated with various concentrations of GS-002 or PPG for 12 h (right panels), or with 10 μg/mL GS-002 or 5 μg/mL PPG for the indicated time periods (left panels), and total RNA was used to detect ATF-3 mRNA levels by an RT-PCR. (b) Hep3B cells were treated with various concentrations of GS-002 for 12 h (right panels) or with 10 μg/mL GS-002 for the indicated time periods (left panels), and total cell lysates were used to detect ATF-3 protein levels by Western blotting. (c) Hep3B cells were transfected with 0.35 μg of the ATF-Luc-1850 reporter plasmid and 0.15 μg phRL-TK for 24 h and then treated with various concentrations of GS-002 for another 24 h. Total cell lysates were used to detect the luciferase activity as described in Section 2.

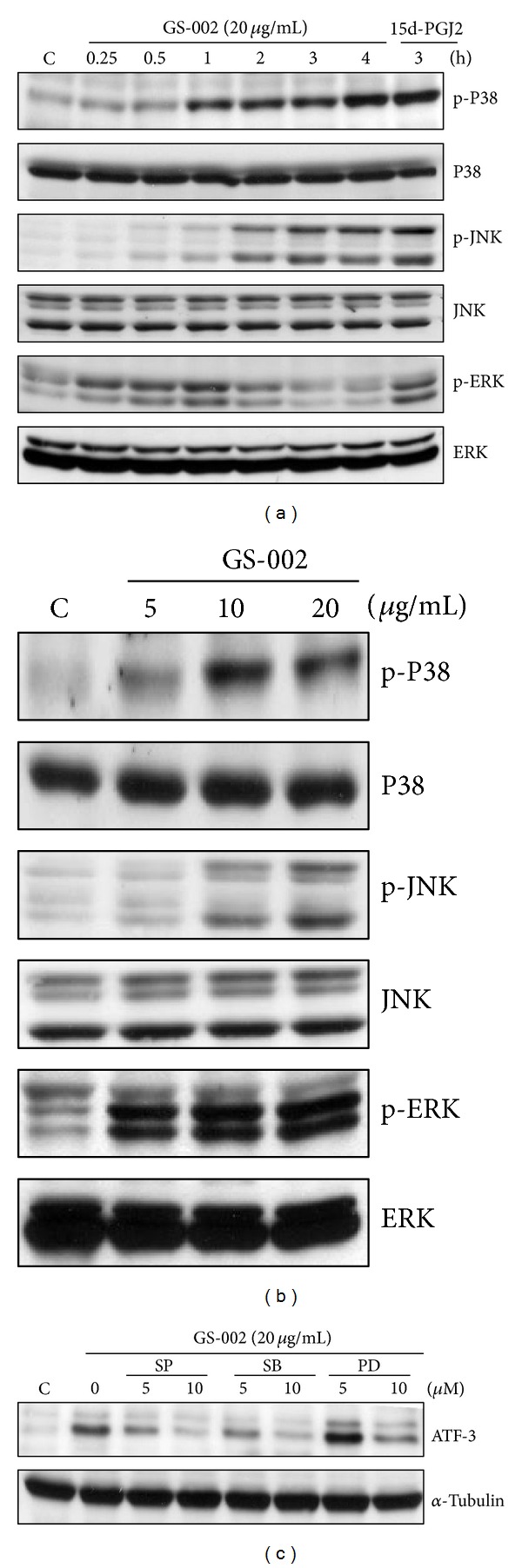

Activation of ATF-3 mainly depends on signaling pathways of MAPKs, which include ERK, JNK, and p38 kinase. To investigate whether GS-002 induced ATF-3 expression mediated by MAPK pathways, we examined phosphorylation levels of p38, JNK, and ERK in GS-002-treated cells. As shown in Figures 6(a) and 6(b), 20 μg/mL GS-002 markedly increased phosphorylation levels of p38, JNK, and ERK. To further demonstrate the importance of the activation of p38, ERK, and JNK in ATF-3 expression in GS-002-treated cells, SB203580, PD98059, and SP600125 were used to, respectively, inhibit the activities of p38, ERK, and JNK. As shown in Figure 6(c), SB203580, PD98059, and SP600125 markedly inhibited ATF-3 protein expression of GS-002-treated cells. The results suggest that ATF-3 expression is mainly mediated by activation of MAPK pathways in GS-002-treated cells.

Figure 6.

The propolis derivative, GS-002, induced ATF-3 expression that was mediated by MAPK pathways. Hep3B cells were treated with (a) 20 μg/mL GS-002 for the indicated time periods, or (b) with various concentrations of GS-002 for 1 h. Total cell lysates were used to detect protein expressions of p38, phosphor-p38 (p-p38), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), phospho-JNK (p-JNK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and phospho-ERK (p-ERK) by Western blotting. Ten micrograms of 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) was used as a positive control. (c) Hep3B cells were pretreated with 5 and 10 μM of the p38 inhibitor, SB203580, the ERK inhibitor, PD98059, or the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, for 90 min, then treated with GS-002 (20 μg/mL) for another 12 h, and the ATF-3 protein level was detected by Western blotting.

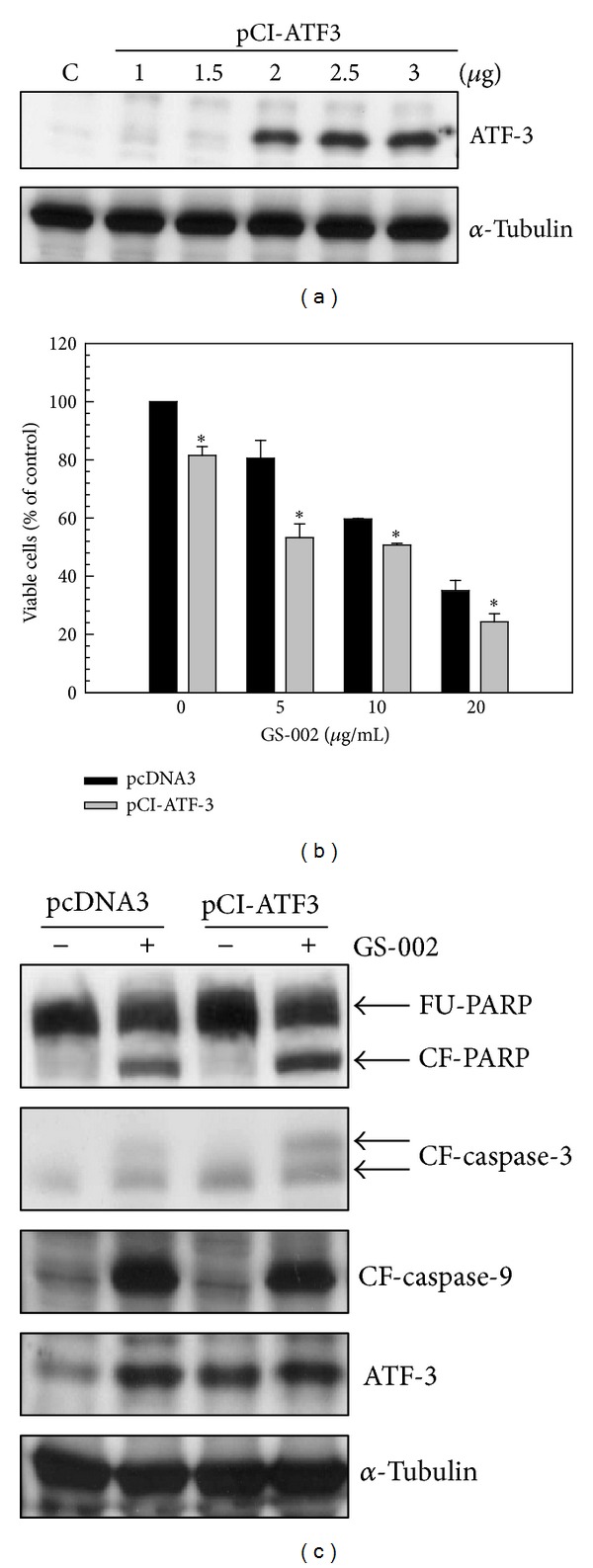

3.4. Overexpression of ATF-3 Enhanced Apoptosis in GS-002-Treated Cells

To understand the role of ATF-3 in GS-002-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cells, Hep3B cells were transitionally transfected with the ATF-3 expression plasmid, pCI-ATF3. As shown in Figure 7(a), transfection with >2 μg of pCI-ATF3 plasmid significantly increased ATF-3 protein expression. Induction of apoptosis was significantly enhanced by transfection with the pCI-ATF3 plasmid at various doses of GS-002 (Figure 7(b)), indicating that GS-002 induced greater cell apoptosis in ATF-3-overexpressing cells than in control cells. The cleaved forms of PARP and caspase-3 also increased in ATF-3-overexpressing cells (Figure 7(c)). These results suggest that induction of apoptosis by GS-002 is mediated through an ATF-3-dependent pathway.

Figure 7.

Overexpression of ATF-3 resulted in enhancement of cell apoptosis in human hepatoma cells treated with the propolis derivative, GS-002. (a) Hep3B cells were transfected with various doses of the pCI-ATF3 plasmid for 24 h, and total cell lysates were used to detect the ATF-3 protein level by Western blotting. (b) and (c) Hep3B cells were transfected with 2 μg of the pCI-ATF3 plasmid for 24 h and then treated with GS-002 for another 24 h. (b) The viable cell number was determined by a crystal violet dye. Values are presented as the mean ± SE of triplcate tests. *P < 0.05 versus individual pcDNA3-transfected control cells. (c) Total cell lysates were used to detect protein expression of the full-length PPAR (FU-PPAR), cleaved form of PPAR (CF-PPAR), cleaved form of caspase-3 (CF-caspase-3), cleaved form of caspase-9 (CF-caspase-9), ATF-3, and α-tubulin by Western blotting.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the propolis derivative, GS-002, has the ability to inhibit cell proliferation and induce cell apoptosis in human hepatoma cells by a crystal violet assay, flow cytometry analysis, and Western blotting. GS-002 further activated ER stress and ATF-3 expression through MAPK pathways. Overexpression of ATF-3 significantly decreased cell proliferation and enhanced cell apoptosis by the transient transfection with an ATF-3 expression plasmid in GS-002-treated cells. These results therefore suggest that ATF-3 might play a key role in GS-002-induced apoptosis, and GS-002 has the potential to be developed as an antitumor drug.

PPG was isolated from Taiwanese propolis. It was demonstrated that it could inhibit C6 glioma cell proliferation through a caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway [26]. Animal experiments indicated that PPG was able to inhibit C6 glioma cell growth in nude mice. In this study, we also found that its derivative, GS-002, had the ability to inhibit human hepatoma cell proliferation through activation of caspase cascades and the proapoptotic Bad protein. Interestingly, PPG did not induce ATF-3 expression compared to GS-002 in hepatoma cells (Figure 5(a)). This finding suggests that PPG and its derivative, GS-002, induce cell apoptosis through different signal pathways. However, GS-002 might also target other molecules which then contribute to cell apoptosis. At least, we found that ER stress increased under GS-002 treatment, but PPG did not seem to induce ER stress in hepatoma cells (unpublished data).

ATF-3 is an adaptive-response gene that regulates gene expressions to adapt to cellular microenvironmental changes [31]. Many publications indicated that ATF-3 is involved in several physiologic and pathologic processes including homeostasis, wound healing, cell adhesion, cancer-cell invasion, apoptosis, and other signal transduction pathways [32, 33]. Previous studies demonstrated that DNA damage stress, such as ionizing radiation (IR), UV radiation, and methyl methanesulphonate, can induce ATF-3 expression through different signal pathways. Overexpression of ATF-3 results in inhibition of cell proliferation, indicating that ATF-3 also plays a negative role in cell growth in response to DNA-damaging stresses [34]. Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6), a tumor suppressor and transcription factor, binds to the ATF-3 gene promoter and induces ATF-3 expression. However, knockdown of ATF-3 in these cells significantly blocked KLF6-induced apoptosis. Therefore, ATF3 is a key mediator of KLF6-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells [35]. Another experiment found that knockdown of the ATF-3 gene in mouse embryonic fibroblasts also reduced the sensitivity of cells to UV-induced apoptosis [36]. On the other hand, previous studies also found that ATF-3 has an oncogenic role. Bandyopadhyay et al. demonstrated that the tumor metastasis suppressor gene, Drg-1, inhibited the invasive ability of prostate cancer cells via downregulating expression of the ATF3 gene [37]. Moreover, another report suggested that ATF-3 has a potential dichotomous role in cancer development, since ATF3 was found to enhance apoptosis in untransformed cells but prevented apoptosis in malignant cells [12]. In this study, overexpression of ATF-3 enhanced GS-002-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cells, indicating that ATF-3 has a negative role in cell proliferation and is a key mediator in GS-002-induced apoptosis.

Regarding the inductive signal pathways of ATF-3 expression, reports indicated that ATF-3 can be induced by several different pathways. Kool et al. demonstrated that ATF-3 expression by IR was mediated by the signaling pathways of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM), Nibrin1, JNK, and p38 [38]. An experiment with UV-induced apoptosis found that p38 and JNK signaling pathways were involved in the induction of ATF-3 [39]. The induction of ATF-3 by anisomycin treatment was also mediated through a MAPK pathway in HeLa cells. p38 is a major contributor to the induction of ATF-3 compared to two other MAPK members, ERK and JNK [31]. In this study, we found that phosphorylation levels of the MAPK members, ERK, JNK, and p38, significantly increased after GS-002 treatment. Using MAPK-specific inhibitors reversed the increase in ATF-3 expression in GS-002-treated hepatoma cells (Figure 6). These results suggest that all MAPK members are important to ATF-3 induction in GS-002-treated cells. On the other hand, many studies have demonstrated that ATF-3 is a ER-stress responsive gene [40]. In this study, we demonstrated that the induction of ATF-3 might be mediated by MAPK signaling pathways in GS-002-treated cells. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the induction of ATF-3 is mediated through ER-stress activation pathway.

A previous report found that the induction of ATF-3 by IR in mouse thymus cells requires p53 [41]. When cells suffer injury, regardless of the state of the intracellular p53, ATF-3 is activated in a variety of cancer cells. ATF-3 expression plays a negative regulatory role in cell growth [34]. In this study, we found that GS-002 significantly induced ATF-3 expression and apoptosis in p53-null Hep3B cells, indicating that GS-002 induced ATF-3 in a p53-independent manner, and GS-002 was able to induce apoptosis in those cancer cells even with mutant p53. We cannot rule out the possibility that GS-002 can also induce ATF-3 expression through a p53-dependent pathway in other tissue types.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

Ming-De Yan and Yu-Chih Liang contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants from the National Science Council (NSC98-2320-B-038-005-MY3) and Taipei Medical University's Wan Fang Hospital (101TMU-WFH-08).

References

- 1.Befeler AS, Bisceglie AM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(6):1609–1619. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(supplement 1):S27–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(10):745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Borràs J. Epidemiology of primary liver cancer. Seminars in Liver Disease. 1999;19(3):271–285. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hai T, Liu F, Coukos WJ, Green MR. Transcription factor ATF cDNA clones: an extensive family of leucine zipper proteins able to selectively form DNA-binding heterodimers. Genes and Development. 1989;3(12):2083–2090. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen BPC, Wolfgang CD, Hai T. Analysis of ATF3, a transcription factor induced by physiological stresses and modulated by gadd153/Chop10. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1996;16(3):1157–1168. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hai T, Wolfgang CD, Marsee DK, Allen AE, Sivaprasad U. ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expression. 1999;7(4–6):321–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, et al. Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature. 2006;441(7090):173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature04768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suganami T, Yuan X, Shimoda Y, et al. Activating transcription factor 3 constitutes a negative feedback mechanism that attenuates saturated fatty Acid/Toll-like receptor 4 signaling and macrophage activation in obese adipose tissue. Circulation Research. 2009;105(1):25–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamura K, Hua B, Adachi S, et al. Stress response gene ATF3 is a target of c-myc in serum-induced cell proliferation. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24(14):2590–2601. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelzer AE, Bektic J, Haag P, et al. The expression of transcription factor activating transcription factor 3 in the human prostate and its regulation by androgen in prostate cancer. Journal of Urology. 2006;175(4):1517–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin X, DeWille JW, Hai T. A potential dichotomous role of ATF3, an adaptive-response gene, in cancer development. Oncogene. 2008;27(15):2118–2127. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janz M, Hummel M, Truss M, et al. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by high constitutive expression of activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), which promotes viability of Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells. Blood. 2006;107(6):2536–2539. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S, Kim J, Yamaguchi K, Eling TE, Baek SJ. Indole-3-carbinol and 3,3′-diindolylmethane induce expression of NAG-1 in a p53-independent manner. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;32(1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitlock NC, Bahn JH, Lee S, Eling TE, Baek SJ. Resveratrol-induced apoptosis is mediated by early growth response-1, Krüppel-like factor 4, and activating transcription factor 3. Cancer Prevention Research. 2011;4(1):116–127. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S-H, Bahn JH, Whitlock NC, Baek SJ. Activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) controls tolfenamic acid-induced ATF3 expression via MAP kinase pathways. Oncogene. 2010;29(37):5182–5192. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St. Germain C, Niknejad N, Ma L, Garbui K, Hai T, Dimitroulakos J. Cisplatin induces cytotoxicity through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways and activating transcription factor 3. Neoplasia. 2010;12(7):527–538. doi: 10.1593/neo.92048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brüning A, Burger P, Vogel M, et al. Bortezomib treatment of ovarian cancer cells mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis. Investigational New Drugs. 2009;27(6):543–551. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi K, Lee S, Kim J, Wimalasena J, Kitajima S, Baek SJ. Activating transcription factor 3 and early growth response 1 are the novel targets of LY294002 in a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-independent pathway. Cancer Research. 2006;66(4):2376–2384. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyer VR, Eisen MB, Ross DT, et al. The transcriptional program in the response of human fibroblasts to serum. Science. 1999;283(5398):83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allan AL, Albanese C, Pestell RG, LaMarre J. Activating transcription factor 3 induces DNA synthesis and expression of cyclin D1 in hepatocytes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(29):27272–27280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin X, Wolford CC, Chang Y, et al. ATF3, an adaptive-response gene, enhances TGFβ signaling and cancer-initiating cell features in breast cancer cells. Journal of Cell Science. 2010;123(20):3558–3565. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan L, della Coletta L, Powell KL, et al. Activation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway in ATF3-induced mammary tumors. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016515.e16515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khalil ML. Biological activity of bee propolis in health and disease. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2006;7(1):22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burdock GA. Review of the biological properties and toxicity of bee propolis (propolis) Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1998;36(4):347–363. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(97)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang W, Huang C, Wu C, et al. Propolin G, a prenylflavanone, isolated from Taiwanese propolis, induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in brain cancer cells. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(18):7366–7376. doi: 10.1021/jf0710579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Chen S, Lin C, Tsai S, Liang Y. Inhibition of melanoma growth and metastasis by combination with (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and dacarbazine in mice. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2001;83(4):631–642. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang Y, Chuang M, Ho F, et al. 15,16-dihydrotanshinone I, a compound of salvia miltiorrhiza bunge, induces apoptosis through inducing endoplasmic reticular stress in human prostate carcinoma cells. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/865435.865435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu D, Liang H, Chen C, et al. Switch activation of PI-PLC downstream signals in activated macrophages with wortmannin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1773(6):869–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfgang CD, Chen BPC, Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ, Hai T. gadd153/Chop10, a potential target gene of the transcriptional repressor ATF3. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1997;17(11):6700–6707. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu D, Chen J, Hai T. The regulation of ATF3 gene expression by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Biochemical Journal. 2007;401(2):559–567. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen-Jennings AE, Hartman MG, Kociba GJ, Hai T. The roles of ATF3 in glucose homeostasis. A transgenic mouse model with liver dysfunction and defects in endocrine pancreas. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(31):29507–29514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishiguro T, Nagawa H. Expression of the ATF3 gene on cell lines and surgically excised specimens. Oncology Research. 2000;12(4):181–183. doi: 10.3727/096504001108747666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan F, Jin S, Amundson SA, et al. ATF3 induction following DNA damage is regulated by distinct signaling pathways and over-expression of ATF3 protein suppresses cells growth. Oncogene. 2002;21(49):7488–7496. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu D, Wolfgang CD, Hai T. Activating transcription factor 3, a stress-inducible gene, suppresses ras-stimulated tumorigenesis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(15):10473–10481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang X, Li X, Guo B. KLF6 induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells through up-regulation of ATF3. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;283(44):29795–29801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802515200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandyopadhyay S, Wang Y, Zhan R, et al. The tumor metastasis suppressor gene Drg-1 down-regulates the expression of activating transcription factor 3 in prostate cancer. Cancer Research. 2006;66(24):11983–11990. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kool J, Hamdi M, Cornelissen-Steijger P, van der Eb AJ, Terleth C, van Dam H. Induction of ATF3 by ionizing radiation is mediated via a signaling pathway that includes ATM, Nibrin1, stress-induced MAPkinases and ATF-2. Oncogene. 2003;22(27):4235–4242. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turchi L, Aberdam E, Mazure N, et al. Hif-2alpha mediates UV-induced apoptosis through a novel ATF3-dependent death pathway. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2008;17(9):1472–1480. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koh I, Lim JH, Joe MK, et al. AdipoR2 is transcriptionally regulated by ER stress-inducible ATF3 in HepG2 human hepatocyte cells. FEBS Journal. 2010;277(10):2304–2317. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amundson SA, Bittner M, Chen Y, Trent J, Meltzer P, Fornace AJ., Jr. Fluorescent cDNA microarray hybridization reveals complexity and heterogeneity of cellular genotoxic stress responses. Oncogene. 1999;18(24):3666–3672. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]