Abstract

Background

Partners of men treated for prostate cancer report more emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of prostate cancer than the men report; the duration of distress for partners is seldom examined.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine the long-term effects of prostate cancer treatment on partners’ appraisal of their caregiving experience, marital satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life (QOL) and factors related to these variables.

Methods

This exploratory study evaluated QOL among spouses of prostate cancer survivors at 24 months after treatment. Partners completed a battery of self-report questionnaires in a computer-assisted telephone interview.

Results

The sample consisted of 121 partners with average age of 60 years. There was a significant relationship between partners’ perceptions of bother about the man’s treatment outcomes and negative appraisal of their caregiving experience and poorer QOL. Younger partners who had a more negative appraisal of caregiving also had significantly worse QOL.

Conclusions

Men’s treatment outcomes continued to bother the partner and resulted in more negative appraisal and lower QOL 2 years after initial prostate cancer treatment. Younger partners may be at greater risk of poorer QOL outcomes especially if they have a more negative view of their caregiving experience.

Implications for Practice

Findings support prior research indicating that prostate cancer affects not only the person diagnosed with the disease but also his partner. Partners may benefit from tailored interventions designed to decrease negative appraisal and improve symptom management and QOL during the survivorship period.

Keywords: Age, Caregivers, Family, Prostate cancer, Quality of life, Spouses

Prostate cancer remains the most common form of non-cutaneous cancer affecting men. A very high percentage of these men respond to treatment and are living with symptoms associated with the disease and the outcomes of treatment over an extended period. Although treatment options vary, these options often result in changes within the family that affect the quality of life (QOL) of the couple.1–3 Spouses play a central role in men’s choice of treatment4 and in maintaining men’s QOL5,6 and are the major providers of emotional support7,8; however, there is an emotional cost.9 Although spouses report more emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of prostate cancer than their husbands report,10,11 the duration of distress for spouses is seldom examined. The overall purpose of this study was to determine the long-term effects of certain medical and demographic factors on spouses’ appraisal of their caregiving experience, sexual satisfaction, marital satisfaction, and QOL at 24 months following treatment. This study expanded on a large, multisite (6 sites across the United States) prospective study being conducted with prostate cancer patients, which also evaluated spouses’ satisfaction with their husbands’ medical treatment.9 The specific objectives of this study were to (1) describe the multidimensional QOL, marital satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction of spouses of men treated for prostate cancer at 2 years following treatment and (2) identify factors associated with spouse’s appraisal of caregiving, sexual satisfaction, marital satisfaction, and QOL.

Theoretical Perspective and Review of Literature

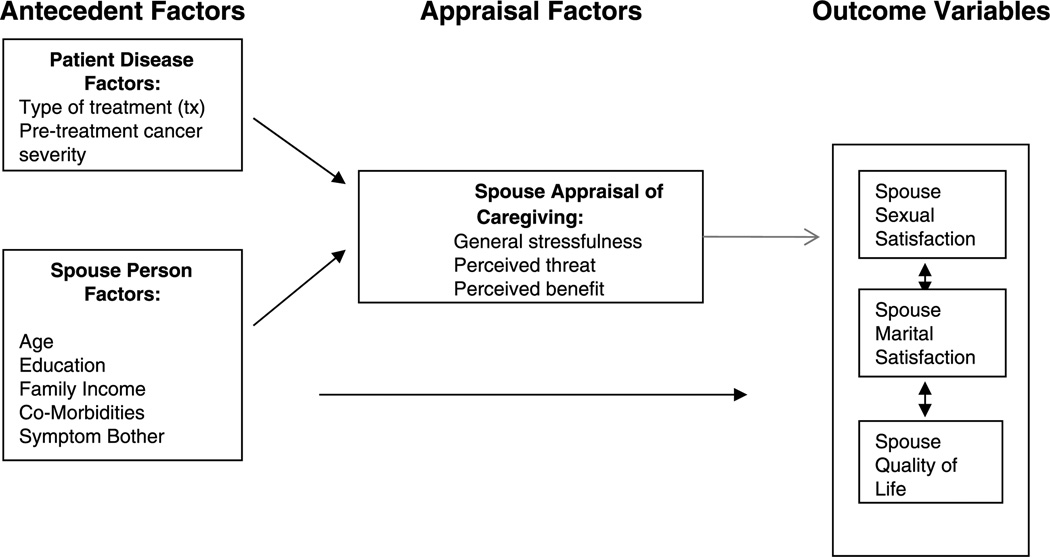

The stress-coping model adopted from Lazarus and Folkman12 served as the theoretical framework that guided the development of this study of spouse-caregivers’ experiences. According to the model (Figure), selected patient disease factors and preexisting spouse personal factors may influence how spouses appraise a caregiving experience and manage the demands related to it. These factors can affect sexual satisfaction, marital satisfaction, and the QOL of the individual.

Figure.

Conceptual framework of factors affecting spouses’ quality of life.

Antecedent Factors

Patient disease factors include the type of treatment men receive for prostate cancer, which is related to the type of symptoms that they experience. Many studies have reported that bowel problems, bladder difficulties, and sexual dysfunction occur following treatment for prostate cancer. Incontinence, impotence, and loss of libido affect the lives of both the patient and his spouse13,14 and, in turn, may affect each person’s QOL.15 Other research has shown that the severity of the disease at the time of diagnosis affects the appraisal of the patient and the spouse. Severity indicates how far the disease has spread within the prostate, to nearby tissue, and to other organs. The severity of disease is an important factor in selecting treatment as well as in predicting prognosis. Pretreatment cancer severity may affect a spouse’s appraisal of her husband’s illness. A higher cancer index score may cause appraisal of more threat related to prostate cancer.16

Spouse factors are preexisting characteristics of the spouse that include demographic factors: age, education, family income, comorbidities, and the spouse’s own bother related to the husband’s treatment effects. Younger age in couples managing an illness has been associated with higher psychological distress, whereas older age has been associated with lower psychological distress.17 Educational level has been associated with more perceived benefit in breast cancer survivors,18 but in prostate cancer spouses, less education has been associated with more spousal distress.19 Lower income or changes in income resulting from treatment for prostate cancer may affect the resources available to help the couple cope with the treatment outcomes and therefore cause more perceived threat. The health status of the spouse also can affect appraisal of caregiving and QOL. Physical changes associated with the development of comorbid conditions associated with aging may have a negative effect on the spouse’s appraisal of caregiving.20

The type of treatment selected for prostate cancer is related to the type of symptoms that men experience. Changes related to the spouse’s treatment adverse effects, as discussed above, can affect spouses’ appraisal of the patient’s illness and consequently diminish the QOL of the couple.2,5,8,21 A decrease in the patient’s energy level and an increase in urinary frequency have been associated with a worsening of QOL in the spouse.8 Litwin et al22 found that sexual function was significantly related to marital satisfaction in prostate cancer couples.

Appraisal Factors

Appraisal of caregiving refers to the spouse’s evaluation of the experience of providing care and consists of 3 components: general stress, perceived threat, and perceived benefit (Figure). Studies indicate that the degree of perceived general stress and perceived threat is directly related to negative appraisal by the person. On the other hand, higher perceived benefit is inversely related to negative appraisal of illness. Furthermore, negative appraisal has been associated with poorer QOL outcomes in cancer patients and their caregivers.8,13,23

General stress associated with caregiving can diminish the QOL of the caregiver. Soloway et al24 found that spouses of prostate cancer patients reported more emotional distress associated with the diagnosis than did their husbands; as the man’s problems increased, there was a reciprocal decrease in QOL of the spouse. Spouses express ongoing worries about the patient’s illness that disturbs their sleep and sense of well-being,14 which may affect the spouses’ appraisal of the patient’s illness and in turn the spouse’s QOL.

Perceived threat, harm, or loss that is anticipated, although identified less often in men treated for prostate, has been associated with mood disturbance.25,26 Furthermore, in patients, age had an inverse relationship with threat appraisal.27 No studies in spouses were found in which threat was a variable studied.

Although a cancer diagnosis can cause distress, there is a growing body of literature that suggests that there may also be beneficial effects associated with the illness. There is some evidence that stressful events can result in a personal growth through improved self-understanding and increased value of being with family and friends.14,28 Some couples have expressed positive changes as a result of their experiences including development of closer relationships, more appreciation of life, recognition of positive qualities and strengths, and improved health practices.14,29,30

Sexual Satisfaction

Sexuality has been found to be a critical component of health-related QOL in patients with prostate cancer. In a recent study of couples in the early posttreatment phase, problems with sexual function were reported more often by the spouse than the patient.31 Additional research is needed to better understand the long-term effect of living with prostate cancer on sexual satisfaction.

Marital Satisfaction

Research on women with breast cancer found that the appraisal of illness negatively affected marital adjustment, which in turn affected marital satisfaction and family life.32 Research in prostate cancer spouses on the effect appraisal of caregiving has on spouses’ marital satisfaction is not well understood.

QUALITY OF LIFE

Quality of life is defined as an overall experience of physical, functional, psychological, and social well-being.33 Research has shown that cancer, in general, affects the QOL of the family,8 but that prostate cancer in particular so strongly affects the spouse as well as the patient it has been referred to as a “relationship disease.”34 Spouses take on the role of maintaining emotional balance, internalizing their feelings, and trying to maintain a positive outlook for their husbands.2,4,35 because the spouse is a major source of support for the patient with prostate cancer, the spouses’ response to treatment outcomes can potentially affect the quality of patients’ lives as well as their own.1,31,36

In summary, most psychosocial studies cited were conducted shortly after treatment. Consequently, the persistence of treatment effects on sexual or marital satisfaction and QOL in longterm survival is not well understood. Prior research in prostate cancer seldom addresses the QOL of spouses, even though research has shown that the QOL of one member of the dyad affects the QOL of the other. This study attempts to examine these long-term effects for the spouse.

Methods

Design

This was a companion study within a prospective longitudinal cohort study of men undergoing treatment for localized prostate cancer and their spouses, PROSTQA [9], who were recruited between March 2003 and March 2006 at 9 university-affiliated hospitals. Patients had elected treatment for localized prostate cancer with radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or brachytherapy. The primary purpose of the companion study was to determine the long-term effects of prostate cancer treatment on spouses’ appraisal of caregiving, sexual satisfaction, marital satisfaction, and QOL. Spouses participating in the parent study were recruited for the companion study fromall sites of the parent study9 when their partners reached the 24-month follow-up from their primary prostate cancer treatment. All patients and partners provided informed consent.

Sample

The sample consisted of 121 spouses of men treated for prostate cancer: 119 were female partners and 2 were male partners. No significant differences were found between the female and male spouses. In the parent study, spouses were eligible to participate if they were identified by the patient as his spouse (included female or male spouses with or without marital ties, but who cohabited in the same household and were involved with the patient for more than a year), were mentally and physically able to participate, and spoke sufficient English to participate. Of the 685 spouses participating in the PROSTQA cohort study, 186 had not reached the 24-month time point at the start of this study in 2006 and were therefore eligible for this study. Spouses participating in the parent study were invited to participate in this companion study between December 2006 and April 2008. Of the eligible 186 spouses, 65 spouses did not complete the 24-month study interview. Nine spouses were not eligible because they were out of the main study (they withdrew or died or the patient withdrew or died), 14 missed the 24-month interview for both studies, 42 spouses declined participation in this additional study, resulting in the final sample of 121.

Procedure

After providing informed consent for the supplemental questions of the companion study, spouses completed a battery of self-report questionnaires in a computer-assisted telephone interview.

ANTECEDENT VARIABLES

Patient Disease Factors

Information about the patient’s type of treatment (prostatectomy, brachytherapy, external beamradiation, and use of neoadjuvant hormonal therapy) and pretreatment cancer severity (Gleason score) was obtained from the patient’s medical record. This patient information was collected at baseline in the parent study.

Spouse Person Factors

Demographics were measured with the Risk for Distress (formerly known as Omega Screening Questionnaire as developed by Weisman and Worden37 and adopted by Mood.38 The Risk for Distress is composed of 4 parts: (a) demographic and background information, (b) health history, (c) inventory of current concerns, and (d ) symptom scale. Two parts of the Risk for Distress, the demographic information section and the health history, were used to measure spousal person factors. Both parts have shown high reproducibility (>95%). The demographic section includes questions about the respondent’s age, education, and income at the time of the patient’s treatment.

Spouse Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite,1 which consists of 6 questions that measure spouses’ perception of bother (how much of a problem to the spouse, ranging from 1 = no problem to 5 = big problem) caused by patient’s prostate cancer posttreatment symptoms (urinary, sexual, bowel, and hormonal).

APPRAISAL

Appraisal was measured with the Appraisal of Caregiving Scale (ACS) as developed by Oberst39 and modified for this study. This scale is grounded in the cognitive-transactional theories of stress and coping. This instrument is most appropriately used after the stressful encounter has occurred and coping has begun, as was the case in this study. The original instrument was modified based on recent research and the need to adapt the instrument for a phone survey. The Brief ACS consists of 9 items and measures 2 types of stressful appraisals, general stressfulness and perceived threat, and 1 type of positive (nonstressful) appraisal, perceived benefit. All items were taken from the original instrument. The original instrument items were content validated by family caregivers, a panel of clinical experts, and a panel of experts familiar with the theory. Construct validity is well established. The intensity of each item is measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale. There are 3 items measuring general stressfulness, 3 items measuring perceived threat, and 3 items measuring perceived benefit. Mean scores were calculated, with higher scores indicating greater general stressfulness, perceived threat, or perceived benefit appraisals. The 3 subscales were used separately in subsequent analysis.

The ACS has been used in a variety of populations including caregivers of cancer patients. Studies that have used the ACS used a summative score for the entire scale.31,40 In the original work by Oberst,39 the internal consistency α coefficient for the general stressfulness scale was .73, for the perceived threat scale is .90, and for the perceived benefit scale is .74. The α coefficient for the general stressfulness scale in this study was .69, for the perceived threat scale is .67, and for the perceived benefit scale is .82.

MARITAL SATISFACTION

Satisfaction with the marital relationship was assessed with the Brief Version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS),41,42 a 4-item instrument that measures couple satisfaction with the relationship (the degree to which the couple is satisfied with the present state of the relationship and its commitment to continuance). A total marital satisfaction score was calculated as the sum of the items on the scale. Higher scores represent more distress in the marital relationship. Comparison of the DAS-4 to the DAS-32 indicates that the brief version is a comparable measure of couple satisfaction.42 This scale has been used to assess marital satisfaction in cancer patients.43,44 In the original work by Sabourin et al,42 the α coefficient for the DAS-4 was between .84 and .92. The α coefficient for the DAS-4 in this study was .57. Marital satisfaction may include other factors not measured in this population, limiting the reliability of the DAS.

SEXUAL SATISFACTION

Satisfaction with the sexual relationship in the marriage was measured by using the Sexual Satisfaction Scale (SSS), which was investigator developed to supplement the DAS and focuses specifically on sexual satisfaction of spouses of men with prostate cancer. The items were content validated by an expert in sexuality in older adults and an expert in prostate cancer research. The 3-item questionnaire measures satisfaction with relationship intimacy, the affect of prostate cancer treatments on the sexual relationship, and overall sexual satisfaction. The intensity of each item is measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating greater sexual satisfaction. Internal consistency reliability for this study was established at .80.

Quality of life was measured using 2 QOL scales, a generic QOL scale (Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey [MOS SF-12])45 and a cancer-specific QOL scale developed for caregivers of cancer patients (Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer Scale [CQOLC]).46 The MOS SF-12 consists of 12 items that form a physical component (PCS) and mental health component (MCS) summary scale. Responses are made in different multiple-choice formats. Extensive psychometric testing has been completed on this instrument, including studies with cancer patients, and has shown strong evidence of validity and reliability.

The CQOLC was developed specifically to measure the QOL of caregivers of patients with cancer.46 The CQOLC consists of 35 items using a 5-point Likert-type scale. The maximum total score is 140. Higher scores reflect better QOL. The instrument was tested in a group of family caregivers of patients with lung, breast, or prostate cancer receiving curative treatment. The α coefficient reliability for this study was .87. The instrument had good convergent validity with other QOL and emotional distress measures. Divergent validity with measures of physical health, social support, and social desirability also was reported. The instrument was found to be responsive to changes in health state of the patient as well.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables in the data set. For the description of spouse’s marital relationship, sexual satisfaction, and QOL, summary scores for the DAS-4, SSS, SF-12, and the CQOLC were used.

Spearman correlation coefficients were used to examine relationships among variables. Multiple linear regressions were conducted to determine if patient disease factors (type of treatment and pretreatment cancer severity) and spouse characteristics (age, education, health status, and symptom bother) were associated with the appraisal of caregiving, marital satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and QOL.

Results

Description of the Sample

Table 1 describes demographic characteristics of the sample. The table indicates that 98% of the 121 spouses were female, 20% had a high school education or less, 92% were white, 58% were not currently employed, and 42% reported household incomes greater than $100 000. The average age of the spouses was 60 years (range, 40–83 years), and the average age of the patients was 64 years (range, 44–81 years), which was significantly different.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristics | Spouses (n = 121), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 119 (98) |

| Male | 2 (2) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 24 (20) |

| Some college/graduate | 60 (50) |

| Postgraduate | 37 (30) |

| Race | |

| White | 111 (92) |

| Black | 6 (4) |

| Asian | 2 (2) |

| Other | 2 (2) |

| Employment status | |

| No employment | 71 (58) |

| Part-time employment | 20 (17) |

| Full time | 30 (25) |

| Couples’ income | |

| $10 000–$30 000 | 10 (8) |

| $30 001–$100 000 | 58 (48) |

| >$100 001 | 51 (42) |

| Missing data | 4 (2) |

| Treatment | |

| Prostatectomy | 72 (58) |

| Radiation therapy | 21 (17) |

| Brachytherapy | 20 (17) |

| Neoadjuvant + external beam radiation therapy | 7 (6) |

| Neoadjuvant + brachytherapy | 2 (2) |

| Gleason total score (severity) | |

| 6 | 73 (60) |

| 7 | 41 (34) |

| 8 | 5 (4) |

| 9 | 2 (2) |

The table also indicates that prostatectomy (primarily “open” but including a small number of robotically assisted laparoscopic procedures as well) was the modal treatment of the male patients (58%). For analysis, patients who had radiation and radiation plus neoadjuvant therapy were merged into 1 category and those who had brachytherapy and brachytherapy plus neoadjuvant therapy were merged into another category because of the small numbers of cases in these groups.

At the time of diagnosis and treatment, most patients had a Gleason total score of 6, indicating moderate cancer severity. Because of the small number of cases in Gleason 8 and 9 categories, these 2 categories were merged with the Gleason score of 7 to make 1 category, which indicated more disease severity than in the Gleason 6 category. Analysis of these groups showed no significant differences among the groups.

QOL, Marital Satisfaction, and Sexual Satisfaction at 24 Months

In order to describe the long-term QOL of spouses of men treated for prostate cancer, we used means and SD for indicators of QOL of a cohort of spouses from a previous study immediately following treatment and the present cohort of spouses 2 years following treatment (as listed in Table 2). Scores on the QOL scale (SF-12) PCS varied from 19 to 62 and on the mental component from 28 to 72, with higher scores representing better reported QOL. Table 2 indicates the mean score in the sample at 2 years following treatment was 52.24 for the mental component and 49.12 for the PCS. This is greater than the established healthy female population norm of 48 for the MCS and 49 for the PCS (mean score),47 indicating the respondent spouses were, on average, generally satisfied with their current QOL. Two-sample t tests were used to compare spouse mean scores at 2 years with a comparative sample of spouses’ SF-12 mean scores taken immediately following prostate cancer treatment from an earlier study.31 Mean scores for the PCS and MCS of the SF-12 of spouses in the current study did not differ significantly from the comparative sample of spouses just following cancer treatment.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data on Marital Satisfaction, Sexual Satisfaction, and Quality of Life

| Partners at 24 mo |

Comparative Samplea |

2-Sample t |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Range: Min/Max | Mean | SD | t | P |

| Quality of Life SF-12 | |||||||

| Physical component | 49.42 | 9.22 | 19–62 | 48.58 | 10.25 | −0.36 | .56 |

| Mental component | 51.83 | 7.36 | 28–75 | 51.28 | 9.86 | −0.77 | .66 |

| CQOLC | 60.04 | 4.28 | 29–109 | NA | |||

| Marital satisfaction | |||||||

| DAS-4 | 12.54 | 1.49 | 8–17 | NA | |||

| SSS | 9.34 | .26 | 2–15 | NA | |||

Abbreviations: CQOLC, Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer Scale; DAS, Dyadic Adjustment Scale; NA, not available from comparative study; SSS, Sexual Satisfaction Scale; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey.

Higher scores on SSS and SF-12 indicate better sexual satisfaction and quality of life. Higher scores on the DAS-4 and CQOLC indicate less marital satisfaction and lower quality of life.

Sample of spouses; mean age, 64 years; 38 localized; 11 recurrent; 20 advanced disease (n = 69).

The mean scores of the cancer-specific CQOLC scale indicate more variability in the QOL of the spouses. The midpoint of possible scores on this scale was 70, with higher scores indicating poorer QOL. The mean for the CQOLC was 60.04 (SD, 14.28), which is less than midpoint, indicating a slightly higher QOL for many of the spouses in the current study at 2 years’ follow-up.

The mean sexual satisfaction score of the SSS was 9.34 (SD, 2.27), which was above the midpoint (7.5) of possible scores, which indicates that spouses on average were generally satisfied with their sexual relationships.

The mean marital satisfaction score of the DAS-4 for the spouses was 12.54 (SD, 1.49), which was very near the distress cut point for this scale of 13 (distressed), indicating some level of distress in the marital relationship within this group of spouses at 2 years.

Factors Associated With Appraisal, Marital Satisfaction, Sexual Satisfaction, and QOL

We next sought to identify factors associated with spouse appraisal of caregiving, marital satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and QOL. We first examined bivariate correlations among study variables. Correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between the subscales of spouses’ appraisal of caregiving and measures of marital satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and both general and cancer-specific QOL (Table 3). Spouses with a negative perception of caregiving on the threat and stress subscales had lower marital and sexual satisfaction, poorer cancer-specific QOL, and poorer mental QOL at 24 months following treatment. In regard to the benefit subscale, spouses with higher perceptions of benefit had lower marital relationship distress and higher cancer-specific QOL. Physical QOL was not affected by the appraisal variables.

Table 3.

Relationship of Appraisal to Marital Satisfaction, Sexual Satisfaction, and Quality of Life (Spearman Correlation Coefficients)

| Appraisal | DAS-4 | SSS | CQOLC | SF-12 MCS |

SF-12 PCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threat | 0.25a | −0.26b | 0.573a | −0.31a | 0.28 |

| Stress | −0.07 | −0.30a | 0.57a | −0.29b | −0.05 |

| Benefit | −0.19b | −0.06 | 0.25a | 0.32 | 0.22b |

Abbreviations: CQOLC, Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer Scale; DAS, Dyadic Adjustment Scale; MCS, mental health component; PCS, physical component; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey; SSS, Sexual Satisfaction Scale.

P < .01.

P < .05.

Analysis of spouse’s perception of bother about the patient’s treatment outcomes and appraisal of the spouse’s caregiving experience was performed (Table 4). Spouses who perceived more bother related to the patient’s urinary function, bowel function, sexual dysfunction, and problems related to hormone therapy had increased stress and threat on the appraisal subscales. Furthermore, younger spouses expressed more bother related to problems with the patient’s sexual dysfunction.

Table 4.

Relationship of Spouse Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) to Appraisal and Age (Spearman Correlation Coefficients)

| Stress | Threat | Benefit | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem urinary incontinence | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.07 | −0.12 |

| Irritation or blockage | 0.30a | 0.15 | −0.05 | −0.06 |

| Overall urinary function | 0.34a | 0.20b | 0.08 | −0.13 |

| Bowel habits | 0.29a | 0.19b | −0.02 | −0.11 |

| Sexual function | 0.20b | 0.10 | −0.06 | −0.32a |

| Hormone function | 0.40a | 0.26b | 0.07 | −0.17 |

Abbreviation: EPIC, Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Correlation analyses also showed that spouses’ perceptions of bother related to overall urinary incontinence, sexual function, and hormone function and vitality were negatively correlated with sexual satisfaction but had no significant relationship with marital satisfaction (Table 5). Bother related to problems with urinary function, bowel problems, sexual dysfunction, and hormone function and vitality resulted in poorer cancer-specific QOL. Only problems with overall urinary function resulted in spouses’ poorer mental QOL. Symptom bother was not related to spouses’ physical QOL.

Table 5.

Relationship of Partner Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) to Marital Satisfaction, Sexual Satisfaction, and Quality of Life (Pearson Correlation Coefficients)

| DAS-4 | SSS | CQOLC | SF-12 MCS |

SF-12 PCS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem urinary incontinence | −0.13 | −0.24a | 0.13 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| Irritation or blockage | 0.02 | −0.23a | 0.18b | −0.17 | −0.03 |

| Overall urinary function | −0.06 | −0.14 | 0.27a | −0.21b | −0.12 |

| Bowel habits | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.23a | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| Sexual function | 0.02 | −0.36a | 0.19b | −0.12 | 0.06 |

| Hormone function | −0.16 | −0.24a | 0.30a | −0.08 | −0.08 |

Abbreviations: CQOLC, Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer Scale; DAS, Dyadic Adjustment Scale; MCS, mental health component; PCS, physical component; SSS, Sexual Satisfaction Scale.

P < .01.

P < .05.

Multiple regression was used to examine how much variance patient disease factors, including severity of the disease (Gleason score), the type of treatment men received (prostatectomy, brachytherapy, or external beam radiation therapy), spouse characteristics (age, education, family income, and health status), and spouse symptom bother, account for in appraisal of caregiving, marital satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and QOL.

Predictors of Appraisal

Multiple regression analysis conducted on appraisal of caregiving revealed several significant effects. Younger age (F = 9.09, P = .003) and patients treated with radiation therapy (F = 5.36, P = .02) explained 9% of the variance in the appraisal subscale of stress. Younger age also accounted for 4% of the variance in the appraisal subscale of threat. Cancer severity and younger age explained 7% of the variance in the appraisal subscale of benefit. There was no significant effect for other treatment options (radical prostatectomy or brachytherapy), education, income, comorbidities, or spouse symptom bother on the appraisal subscales. Tests for mediation on the appraisal subscales showed that only benefit was a mediator for cancer severity (t = 2.16, P = .03) explaining 3% of the variance.

Predictors of Sexual Satisfaction

We found no significant effect for cancer severity, education, or any of the appraisal subscales on sexual satisfaction. Income (t = 2.31, P = .02) predicted 19% of the variance in sexual satisfaction. Spouse symptom bother related to the patient’s sexual function (t = −6.66, P ≤ .0001) and hormone therapy (t = −2.63, P = .01) predicted 39% of the variance in sexual satisfaction.

Predictors of Marital Satisfaction

Appraisal subscales of threat (t = 2.27, P = .03) and benefit (t = 2.44, P = .02) explained 25% of the variance in marital satisfaction but was not significant in sexual satisfaction.

Predictors of QOL

Fifty-five percent of the variance in cancer-specific caregiver QOL was explained by perceptions of stress (t = 4.00, P = .0001), threat (t = 4.06, P < .0001), and benefit (t = 3.22, P = .002.). Perceptions of threat (t = −2.09, P = .04) and spouse age (t = 2.33, P = .02) also explained 23% of variance in mental QOL (SF-12).

The study found that age had a significant association with spouse QOL. Results indicate that younger spouses (<65 years) had lower cancer-specific QOL (t = −2.03, P = .04 and lower mental QOL (t = 2.80, P = .01). Older age in spouses (t = −2.11, P = .04) and more comorbidities (t = −4.49, P < .0001) explained 37% of the variance on spouses’ physical QOL.

Spouse symptom bother related to the patient’s urinary function (t = 2.12, P = .04) and bowel difficulties (t = 2.76, P = .01) predicted 17% of the variance in cancer-specific caregiver QOL. Spouse symptom bother related to the patient’s urinary function significantly associated with spouse mental QOL (t = −2.14, P = .04) and physical QOL (t = −2.35 P = .02) on the generic QOL measure (SF-12).

Discussion

This study examined spouses’ appraisal of their current caregiving experience 2 years following the patients’ treatment for localized prostate cancer. The study also examined marital satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and general and cancer-specific QOL of spouses 2 years following treatment. Results for aim 1, which was to describe the multidimensional QOL, marital satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction of spouses of men treated for prostate cancer at 2 years following treatment, indicate that spouses’ QOL was generally good on both the generic and cancer-specific QOL measures.

However, there was a subgroup of spouses who had lower cancer-specific QOL mean scores at 24 months. These were spouses who were younger (<65 years), perceived more threat and stress in their caregiving role, and experienced more bother by their husbands’ posttreatment symptoms. Although spouses at 2 years following treatment were generally satisfied with their sexual relationship, spouses’ marital satisfaction scores indicated some marital distress as evidenced by the DAS-4 scores near the distress level. Previous research has found that dyads in relationships that were less satisfying experienced more distress and had been linked to poorer adjustment to the illness.48,49

Factors Associated With Appraisal, Marital Satisfaction, Sexual Satisfaction, and QOL

Cancer severity at the time of treatment, education, comorbidities, and spouse symptom bother were not associated with spouse appraisal. Higher income was associated with sexual satisfaction in this study. Other research has found higher income was related to frequency of sexual activity in middle-aged and older women.50 Cost was a factor in the ability to use treatment measures (such as sildenafil) for sexual dysfunction,51 which may be related to higher sexual satisfaction in this study group among those with higher income. Other findings from this study indicate that spouses who had negative appraisal of their caregiving experience had lower marital and sexual satisfaction and poorer QOL. This was especially evident in younger spouses. Negative appraisal in general was significantly related to lower QOL in younger spouses (69% of the sample were <65 years of age). Fifty percent of the spouses in this study were working, possibly creating stress between job commitment and a desire to be supportive of their husbands. Since patients had treatment for early-stage prostate cancer, younger spouses and their husbands are more likely to live with the aftermath of treatment for a longer period. Because the spouse’s age was significantly different than the age of patient, with many spouses being 4 or more years younger than their husband, spousal negative appraisal could be related to concern about a shortened time together. Interventions to help them manage spousal negative appraisal and improve their QOL would be beneficial. Further analysis revealed significant findings on the subcomponents of the appraisal of caregiving scale (stress, threat, and benefit) for spouses of all ages. Perceptions of threat and general stress associated with caregiving were experienced at 2 years following treatment, creating a negative appraisal of their caregiving experience. Research has also shown that the extent to which spouses perceive their situation as stressful has been associated with less life satisfaction,13 a factor that negatively affects QOL. Research has shown that the spouses’ appraisal of their caregiving experience has a strong influence on QOL.13

At 2 years following treatment, spouses still expressed bother related to the patients’ treatment outcomes. The spouse’s version of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite, which was discussed earlier, is a measure of the spouse’s perception of bother that patients’ symptoms caused spouses.9 Spouses who perceived more bother from the patients’ urinary function, bowel habits, and hormone problems appraised their caregiving situation more negatively and reported a lower QOL. Furthermore, results indicated that younger spouses experienced more bother related to the patient’s sexual function at 24 months following his treatment. Soloway and colleagues24 also found that spouses were distressed by changes in their sexual relationship, and Litwin et al22 found that erectile dysfunction had a significant negative correlation with marital interaction. Study findings support suggestions that sexual counseling offered following a diagnosis of prostate cancer should be extended to spouses as well as the patient to help facilitate the dyad’s successful adjustment to treatment outcomes.

Predictors of Appraisal, Marital Satisfaction, Sexual Satisfaction, and QOL

Younger age was the only significant predictor of negative appraisal (stress and threat) in this study. Cancer severity and younger age predicted a small amount of variance on the benefit subscale. This suggests that younger spouses of men diagnosed with cancer struggle to find some positive aspect to help them cope with their situation. Previous research also found living with prostate cancer influenced younger couples’ view of their daily life, changing priorities and family goals.14 Interventions aimed at positive reframing or finding meaning in difficult situations may help the younger spouse adjust.

Negative appraisal was a significant predictor of marital satisfaction, cancer-specific QOL, and mental QOL but not sexual satisfaction. Living with a cancer diagnosis, even when it has been treated, appears to be a persistent source of distress for spouses. Researchers have found a reciprocal relationship between spouse and patient adjustment.40,52 This finding implies a need for spousal interventions designed to diminish negative appraisal and support positive coping.

Spouse symptom bother related to the patient’s sexual dysfunction and hormone therapy was a significant predictor of sexual satisfaction. Research has shown that partners often report lower level of sexual function than patients,31 but spouses often do not discuss sexual issues with their partner for fear of further increasing the partner’s anxiety related to this issue.24 Spouses may also discount concerns about sexual function in view of the severity of a cancer diagnosis. This suggests the importance of including the spouse in sexual counseling following treatment for prostate cancer. Furthermore, it suggests that interventions designed to facilitate communication within couples managing the aftermath of prostate cancer treatment may be beneficial.

Limitations

While this study provided a closer look at the experiences of spouses of prostate cancer patients at 2 years following treatment, it has some limitations. First, the findings of this study report on one point in time; consequently, causal inferences cannot be made. Second, all variables reported are based on self-report and may not reflect objective distress in spouses. Finally, even though the sample was recruited from multiple sites across the country, it was composed primarily of middle- and upper-middle-class, well-educated, white spouses and therefore is not reflective of the ethnic/racial diversity of the population of dyads living with prostate cancer as a whole. Future studies are needed with ethnic minorities and individuals of lower educational and incomes levels.

Implications for Practice

Findings in this study (continued negative appraisal of their caregiving experience; continued bother from the patients’ urinary function, bowel habits, and hormone problems leading to more negative appraisal of their caregiving situation and a lower QOL) point to the need to include the spouse in follow-up care offered to the patient. Interventions to help spouses manage their negative appraisal and improve their QOL are needed. Interventions aimed at positive reframing or finding meaning in difficult situations may be especially helpful to younger spouses. Interventions designed to facilitate communication within couples managing the aftermath of prostate cancer treatment could decrease negative appraisal. Study findings support suggestions that sexual counseling offered following a diagnosis of prostate cancer should be extended to spouses as well as the patient to help facilitate the dyad’s successful adjustment to treatment outcomes.

Conclusions

This study adds to a growing body of research on spouses of men treated for prostate cancer. Findings support the now well-established concept that prostate cancer affects not only the person diagnosed with the disease but also his spouse. In this study, spouses’ negative appraisal of their caregiving experience had a reciprocal affect on QOL: more negative appraisal resulted in more marital distress, less satisfaction with the sexual relationship, and lower QOL scores. Younger spouses of men with prostate cancer are an at-risk group who may benefit from intervention because they have more negative appraisals and lower QOL. There is a need for even longer-term assessment of spouses of prostate cancer patients because men’s treatment outcomes (urinary function, bowel habits, and hormone symptoms) continue to affect spouses’ QOL for at least 2 years after treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge PROSTQA Data Coordinating Center Project Management, Michigan State University, East Lansing (Ms Hardy); Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts (Ms Najuch and Mr Chipman); Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts (Ms Crociani), grant administration by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Ms Doiron), and technical support from coordinators at each clinical site.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (5R03CA119764-2, Dr Harden, principal investigator; and R01-CA95662, Dr Sanda, principal investigator).

Appendix

PROSTQA Consortium Study Group (study investigators, Data Collection Center, and coordinators): The PROSTQA Consortium includes contributions in cohort design, patient accrual, and follow-up from the following investigators: Meredith Regan (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts); Dr Hembroff (Michigan State University, East Lansing); Dr Wei, Dan Hamstra, Rodney Dunn, Dr Northouse, and David Wood (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor); Eric A. Klein and Jay Ciezki (Cleveland Clinic, Ohio); Jeff Michalski and Adam Kibel (Washington University, St Louis, Missouri); Mark Litwin and Chris Saigal (University of California–Los Angeles Medical Center); Louis Pisters and Deborah Kuban (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas); Howard Sandler (Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California); Jim Hu (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts); Douglas Dahl and Anthony Zietman (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston); and Irving Kaplan and Dr Sanda (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Montie J, et al. Living with prostate cancer: patients’ and spouses’ psychosocial status and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(27):1–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harden J, Schafenacker A, Northouse LL, et al. Couples’ experiences with prostate cancer: focus group research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(4):701–709. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.701-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyman E, Rosner R. Prostate cancer: an intimate view from patients and wives. Urol Nurs. 1996;16(2):37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maliski SL, Heilemann MV, McCorkly R. From “death sentence” to “good cancer”: couples’ transformation of a prostate cancer diagnosis. Nurs Res. 2002;51(6):391–397. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips C, Gray RE, Fitch MI, Labrqcque M, Fergus K, Klotz L. Early postsurgy experience of prostate cancer patients and spouses. Cancer Pract. 2000;8(4):165–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.84009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rondorf-Klym LM, Colling J. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30(2):1–15. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.E24-E32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray RE, Fitch M, Phillips C, Labrecque M, Fergus K. Managing the impact of illness: the experiences of men with prostate cancer and their spouses. J Health Psychol. 2000;5(4):531–548. doi: 10.1177/135910530000500410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornblith A, Herr HW, Ofman US, Scher HI, Holland JC. Quality of life of patient’s with prostate cancer and their spouses: the value of data base in clinical care. Cancer. 1994;73(11):2791–2802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::aid-cncr2820731123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanda MG, Rodney L, Dunn MS, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko CM, Malcarne VL, Varni JW, et al. Problem-solving and distress inprostate cancer patients and their spousal caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0748-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cliff AM, Macdonagh RP. Psychosocial morbididty in prostate cancer: II. A comparison of patients and partners. BJU Int. 2000;86:834–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL. Cancer caregivers’ quality of life: effects of gender, relationship, and appraisal. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(3):294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harden J, Northouse LL, Mood D. Qualitative analysis of couples’ experience with prostate cancer by age cohort. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(5):367–377. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, Ganz PA, Leake GE, Brook RH. Quality of life outcomes in men treated for localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1995;273(2):129–135. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowman KF, Deimling GT, Smerglia V, Sage P, Kahana B. Appraisal of the cancer experience by older long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2003;12:226–238. doi: 10.1002/pon.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deimling GT, Kahana B, Bowman K, Schaefer ML. Cancer survivorship and psychological distress in later life. Psychooncology. 2002;11:479–494. doi: 10.1002/pon.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cimprich B, Ronis DL, Martinez-Ramos G. Age at diagnosis and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(2):85–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.102006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eton DT, Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS. Psychological distress in spouses of men treated for early-stage prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103(11):2412–2418. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harden J. Developmental life stages and couples’ experiences with prostate cancer: review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28(2):85–98. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrader-Bogen CL, Kjellberg JL, McPherson CP, Murray CL. Quality of life and treatment outcomes. Cancer. 1997;79(10):1977–1986. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970515)79:10<1977::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Litwin MS, Nied RJ, Dhanani N. Health-related quality of life in men with erectile dysfunction. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:159–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northouse LL, Mood D, Templin T, Mellon S, George T. Couples patterns of adjustment to colon cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soloway CT, Soloway MS, Kim SS, Kava BB. Sexual, psychological and dyadic qualities of the prostate cancer ‘couple’. BJU Int. 2005;95:780–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad M, Musil CM, Zauszniewski JA, Resnick MI. Prostate cancer: appraisal, coping, and health status. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31(10):34–43. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20051001-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wooten AC, Burney S, Foroudi F, Frydenberg M, Coleman G, Ng KT. Psychological adjustment of survivors of localised prostate cancer: investigating the role of dyadic adjustment, cognitive appraisal and coping style. Psychooncology. 2007;16(11):994–1002. doi: 10.1002/pon.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazanec S, Daly BJ, Douglas S, Musil C. Predictors of psychological adjustment during postradiation treatment transition. West J Nurs Res. 2010;33(4):540–559. doi: 10.1177/0193945910382241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner dS, Cox H. Facilitating post traumatic growth. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2(34):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manne S, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Goldstein L, Fox K, Grana G. Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: patient, partner, and couple. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:442–454. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127689.38525.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calhoun L, Tedeschi R. Beyond recovery from trauma: implications for clinical practice and research. J Soc Issues. 1998;54(2):357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harden J, Northouse LL, Cimprich B, Pohl J, Liang J, Kershaw T. The influence of developmental life stage on quality of life in survivors of prostate cancer and their partners. J Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2(2):84–94. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woods NF, Lewis FM. Women with chronic illness: their views of their families’ adaptations. Health Care Women Int. 1995;16:135–148. doi: 10.1080/07399339509516165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zahn L. Quality of life: conceptual and measurement issues. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17:795–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray RE, Fitch MI, Phillips C, Labrecque M, Klotz L. Presurgery experiences of prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer Pract. 1999;7:130–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders S, Pedro LW, Bantum EO, Galbraith ME. Couples surviving prostate cancer: long-term intimacy needs and concerns following treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2006;10(4):503–508. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Wellisch DK, Spillers RL, Kaw CK, Smith TG. Quality of life of couples dealing with cancer: dyadic and individual adjustment among breast and prostate cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Annu Behav Med. 2008;35:230–238. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weisman AD, Worden JW. The existential plight in cancer: significance of the first 100 days. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1976;7:1–15. doi: 10.2190/uq2g-ugv1-3ppc-6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mood DBJ. Strategies to enhance self-care in radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum (Supplement) 1989;16:143. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oberst MT. Appraisal of Caregiving Scale: Manual for Use. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Northouse LL, Dorris G, Charron-Moore C. Factors affecting couples’ adjustment to recurrent breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00302-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spanier G. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabourin S, Valois P, Lussier Y. Development and validation of a Brief Version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale with a nonparametric item analysis model. Psychol Assess. 2005;17(1):15–27. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chekryn J. Cancer recurrence: personal meaning, communication, and marital adjustment. Cancer Nurs. 1984;7:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manne SL, Alfieri T, Taylor KL, Dougherty J. Spousal negative response to cancer patients: the role of social restriction, spouse mood, and relationship satisfaction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:352–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ware JJ, Kosinski M, Keeler SD. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scale and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H, Friedland J, Cox C. The Caregiver Quality of Life IndexYCancer (CQOLC) scale: development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:55–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1026407010614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13:375–384. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manne S, Dougherty J, Veach S, Kess R. Hiding worries from one’s spouse: protective buffering among cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer Res Ther Control. 1999;8:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banthia R, Malcarne V, Varni JW, Ko CM, Sadler GR, Greenbergs HL. The effects of dyadic strength and coping styles on psychological distress in couples faced with prostate cancer. J Behav Med. 2003;26(1):31–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1021743005541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Addis I, Van Den EEden SK, Wassel-Fyr CL, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS, Thom DH. Sexual activity and function in middle-aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(4):755–764. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000202398.27428.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stroberg P, Hedelin H, Bergstrom A. Is sex only for the healthy and wealthy? J Sex Med. 2007;4(1):176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baider L, Walach N, Perry S, Kaplan De-Nour A. Cancer in married couples: higher or lower distress? J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]