In heart cells, membrane potential and intracellular calcium ([Ca2 +]i) are closely linked. Each time the heart beats, membrane depolarization opens L-type Ca2 + channels in the cell membrane. Ca2 + entering through these channels triggers the release of a larger amount of Ca2 + via ryanodine receptors (RyRs) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane, a process known as CICR, for Ca2 +-induced Ca2 + release. The increase and subsequent decrease in [Ca2 +]i, the Ca2 + transient, is the signal that initiates contraction. Conversely, changes in [Ca2 +]i can alter membrane potential through Ca2 +-dependent ion channels, pumps, and transporters in the cell membrane. Not surprisingly, numerous proteins and pathways are involved in regulating Ca2 + transport in myocytes. When these regulatory systems become disrupted or unstable in disease, Ca2 + transients may be altered, and pathological changes in membrane potential such as arrhythmias can result. Understanding beat-to-beat regulation of CICR is therefore critical to gain insight into Ca2 +-dependent arrhythmias.

Ca2 + transient restitution is one of the fundamental cellular properties important in determining the beat-to-beat stability of CICR. In this context restitution refers to the following: if two Ca2 + transients are triggered in succession, how does the amplitude of the second relative to the first depend on the interval between triggers? Although restitution is straightforward to measure in heart cells, determining the underlying mechanisms is challenging because several time, voltage, and Ca2 +-dependent processes can contribute, including electrical refractoriness, recovery of L-type channels from inactivation, reloading of SR Ca2 + stores, and recovery of RyRs. To infer underlying mechanisms, investigators have used a variety of techniques aimed at separating the contributing processes, such as triggering Ca2 + release via photolytic “uncaging” of Ca2 + from light-sensitive compounds [1] and [2], and pharmacological manipulation of RyR gating [[3], [4], [5] and [6]]. In this issue of the JMCC, Kornyeyev et al. address restitution mechanisms by comparing Ca2 + transients in genetically-modified versus wild-type mice [7]. This represents a novel approach to this question, and the results presented in this clever study provide new information that enhances our understanding of restitution. These data may also have interesting implications for how changes in myocyte Ca2 + regulation can either increase or decrease susceptibility to arrhythmias.

1. Restitution is faster in the absence of calsequestrin

In their study [7], Kornyeyev et al. utilized an established mouse with targeted deletion of type 2 calsequestrin (Casq2), the most abundant SR Ca2 + binding protein [8]. Previous studies with this mouse (Casq2−/−) have shown that it exhibits a phenotype characteristic of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), namely instability of CICR, a tendency towards spontaneous cell-wide Ca2 + waves, and a greater propensity for Ca2 +-dependent arrhythmias [8]. Besides reducing buffering in the SR, Casq2 knockout causes an increase in SR volume, a reduction in the SR accessory proteins junctin and triadin, and possibly a change in RyR gating (see discussion below). In the present study, the authors used pulsed local-field fluorescence microscopy [9] to record optically from a multicellular region in whole hearts. With this technique, they were able to optically measure (in separate experiments) [Ca2 +]i, SR [Ca2 +], and action potentials. The recovery of each process was assessed by delivering two stimuli at a variable interval and plotting the response to the second stimulus as a function of the interval. The authors found that recovery of both Ca2 + transients and SR [Ca2 +] are considerably faster in the Casq2−/− mice compared with the wild-type (Casq2+/+) mice. Recovery of action potentials and L-type Ca2 + current, however, are normal in the Casq2−/− mice. Together, these results therefore indicate that the difference between the groups results from faster recovery of the Ca2 + release process itself, rather than from recovery of the trigger. Thus, RyRs appear to recover from refractoriness more quickly in Casq−/− mice.

2. Restitution of release depends on changes in SR [Ca2 +]

When interpreted in the context of results obtained over the past several years, the data presented by Kornyeyev et al. help us to understand the mechanisms underlying recovery of CICR in heart cells and, by extension, the mechanisms of release termination. For instance, if release terminated due to Ca2 +dependent inactivation on the cytosolic side, and recovery from this process were the rate-limiting step in Ca2 + transient restitution, then knockout of an SR Ca2 + binding protein would have no effect. Thus, the markedly faster restitution observed in cells from Casq2−/− mice implies that changes in SR [Ca2 +] have a much greater effect on restitution than do changes in cytosolic [Ca2 +]. As recently reviewed [10], this result is consistent with several studies on Ca2 + spark termination and recovery over the past decade [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [11] and [12]] that have indicated the importance of dynamic changes in SR [Ca2 +]. Indeed, the study of Kornyeyev et al. is just one of several recent results that argue against an important role for inactivation of RyRs by cytosolic Ca2 + (see Table 1). Together these data have important implications for mathematical models of CICR, since they suggest that models that omit Ca2 +dependent inactivation of RyRs will produce more realistic results than those that continue to assume a prominent role for RyR inactivation in cardiac myocytes (see Table 1).

Table 1.

No physiological role for Ca2 +-dependent inactivation of RyRs?

| Experimental evidence against Ca2+-dependent inactivation of RyRs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Result | Reference | |

| Spontaneous Ca2 + waves persist at sustained cytosolic [Ca2 +] of 50 μM | [24] | |

| Ca2 + spark release flux does not influence level of SR [Ca2 +] at termination | [25] | |

| RyR sensitization does not affect recovery of Ca2 + spark amplitude | [6] | |

| Casq2 knockout accelerates Ca2 + transient restitution | Current study | |

| Mathematical models that assume strong Ca2 +-dependent inactivation of RyRs | ||

| Authors | Year | Reference |

| Wang, Stern, Rios and Cheng | 2004 | [26] |

| Shannon, Wang, Puglisi, Weber and Bers | 2004 | [27] |

| Lee and Keener | 2008 | [28] |

| Liang, Hu and Hu | 2009 | [29] |

| Krishna, Sun, Valderrabano, Palade and Clark | 2010 | [30] |

| Hashambhoy, Greenstein and Winslow | 2010 | [31] |

| Rovetti, Cui, Garfinkel, Weiss and Qu | 2010 | [32] |

| Mathematical models that omit Ca2 +-dependent inactivation of RyRs | ||

| Authors | Year | Reference |

| Sobie, Dilly, Cruz, Lederer and Jafri | 2002 | [11] |

| Restrepo, Weiss and Karma | 2008 | [23] |

| Hartman, Sobie and Smith | 2010 | [33] |

| Gaur and Rudy | 2011 | [34] |

| Williams, Chikando, Tuan, Sobie, Lederer and Jafri | 2011 | [35] |

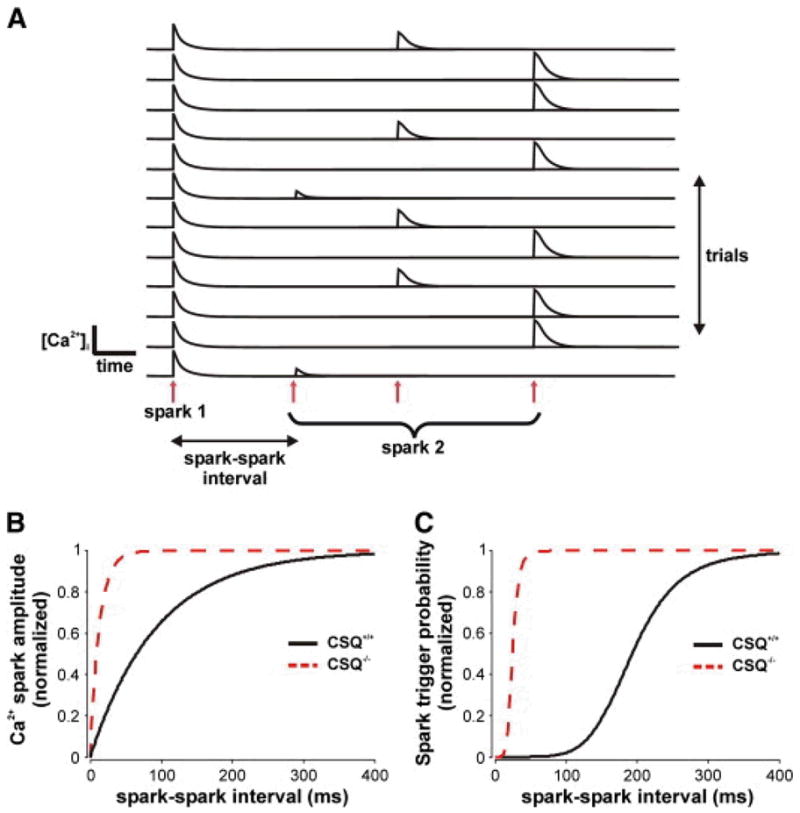

In the present study [7], measurements were made in intact hearts, and each recording reflected the activity of numerous cells. Work at the sub-cellular level has shown, however, that restitution of Ca2 + release from an individual cluster of RyRs can be decomposed into two components, a recovery of Ca2 + spark amplitude and a recovery of Ca2 + spark triggering probability [5] and [6]. To provide additional insight into the results obtained by Kornyeyev et al., we performed simulations of Ca2 + release recovery in the absence of Casq2 using our mathematical model of the Ca2+ spark [6] and [11].

Fig. 1A illustrates schematically the previously described [6] protocol for simulating Ca2 + spark restitution in the model. We opened a single channel within a cluster of stochastically gating RyRs at time t = 0 to potentially trigger a Ca2 + spark, then opened a single RyR again after a specified interval. By running many trials at each interval and computing statistics, we could assess how Ca2 + spark amplitude (Fig. 1B) and Ca2 + spark triggering probability (Fig. 1C) evolved as a function of the interval between programmed RyR openings (see [6] for details). In these simulations we assumed that Casq2 knockout completely eliminated Ca2 + buffering within the junctional SR but caused no additional changes. The model predicts that this change will dramatically accelerate the recovery rates of both Ca2 + spark amplitude and Ca2 + spark triggering probability.

Fig. 1.

Mathematical modeling of Ca2 + spark restitution after Casq2 knockout. (A) As illustrated schematically, Ca2 + spark restitution is simulated by opening an individual RyR at time t = 0, then opening a second RyR at a specified interval. Running repeated trials and collecting statistics allows us to predict how Ca2 + spark amplitude and triggering probability evolve as a function of the interval. The stochastically-gating Ca2 + release unit is a cluster of 28 RyRs, with parameters as in [6]. Model parameters were previously adjusted to describe Ca2 + spark restitution in myocytes from healthy rats. Here, we assume that spark restitution in wild-type (Casq2+/+) mice is similar to that in healthy rats. Probabilities and amplitudes at each interval are mean values based on at least 500 trials. (B) Simulated recovery of normalized Ca2 + spark amplitude in Casq2+/+ (solid line) and Casq2−/− (dashed line) mice. Amplitude restitution in the knockout (time constant = 13 ms) is considerably faster than in the WT mouse (time constant = 94 ms). (C) Recovery of normalized Ca2 + spark triggering probability in Casq2+/+ (solid line) and Casq2−/− (dashed line) mice. Triggering probability recovery is dramatically faster in the knockout (half time = 24.6 ms) compared with the WT mouse (half time = 193 ms). In simulated Casq2−/−mice, [Casq2] in the junctional SR was reduced from 30 mM to 0 mM. Thus, we assumed that Casq2 knockout caused a decrease in SR Ca2 + buffering and no additional alterations.

Interestingly, in the model Casq2 knockout is also predicted to substantially decrease the probability that, in diastole, a spontaneous RyR opening triggers the remaining RyRs in the cluster (44.1% Casq2+/+ vs. 1.23% Casq2−/−). This occurs because, without buffers in the junctional SR, local depletion of SR [Ca2 +] occurs more quickly when RyRs are open. This in turn makes the Ca2 + flux through each spontaneous RyR opening much less likely to trigger its neighbors because the total Ca2+ released during the opening is much smaller. Data obtained in the present study [7] and previously [8], however, suggest that Ca2 + spark triggering is normal in Casq2−/− mice. The model prediction therefore suggests that additional factors besides changes in buffering must be considered to recapitulate the phenotype of the Casq2−/− mouse.

3. Besides acting as a buffer, does Casq2 directly regulate the RyR?

It is intuitive that knockout of anSR Ca2 + buffer will accelerate the rate of recovery of SR [Ca2 +] after release, as the data obtained in the present study demonstrate. The simulation results in Fig. 1 show that this effect would be predicted to cause faster recovery of both Ca2 + sparkamplitude and Ca2 + spark triggering probability. The question arises, then, of whether the reduction in SR buffering in Casq2−/− mice is sufficient to explain the experimental results obtained in the present study and elsewhere.

Although no single result can be considered definitive, several pieces of evidence suggest that Casq2 knockout leads to changes in RyR gating in addition to altered Ca2 + buffering. First, in vitro studies have convincingly demonstrated that Casq2 can directly modulate RyR gating[13] and [14]. Second, data in the present study [7] showed that the degree of SR Ca2 + depletion during a second Ca2 + transient was greater in the Casq2−/− mice when matched to the same relative level of SR [Ca2 +]. Third, the increased diastolic SR Ca2+ leak observed in Casq2−/− mice and the propensity of these mice to develop Ca2 +dependent arrhythmias [8] suggest changes in RyR gating. Finally, the simulation results shown in Fig. 1 also provide a hint that Casq2 knockout may alter RyR function. When SR Ca2 + buffering is reduced in the model and no other changes are made, the simulations predict a dramatic decrease in the frequency of spontaneous Ca2 + sparks. Reproducing the normal or slightly enhanced Ca2 + spark triggering in Casq2−/− mice would therefore require increasing the RyR opening rate (i.e. increasing the sensitivity of RyRs to be activated by [Ca2 +]i), suggesting that RyR gating is altered in the knockout mice.

Some caveats should be mentioned, however. One is that it is difficult to precisely quantify the levels of free SR [Ca2 +] in these mice. Relative changes in SR [Ca2 +] can be measured using an SR-targeted dye as in the present study, but calibration of these dyes is challenging, and absolute levels of SR [Ca2 +] cannot usually be determined. Previous work has documented a slight reduction in total SR [Ca2 +] in Casq2−/− mice [8]; if we assume that roughly half of total SR [Ca2 +] is bound to Casq2 in WT mice [10], this suggests a significant elevation in free SR [Ca2 +] in the knockouts. An additional unresolved question concerns the precise role played by Casq2 in sensing changes in SR [Ca2 +]. RyR gating is known to be affected by SR [Ca2 +], and in vitro studies [13] and [14] suggest that Casq2 influences the ability of the RyR to respond to changes in SR [Ca2 +]. Casq2 knockout might therefore be expected to influence the dependence of RyR gating on SR [Ca2 +], although the quantitative effects of such an alteration remain unclear at present.

4. Is there an optimal speed of Ca2 + release restitution in heart cells?

Terentyev et al. proposed that faster CICR restitution due to decreased Casq2 may explain the increased risk of arrhythmia observed in patients with Casq2 mutations [4]. According to this idea, reduced levels of Casq2 would cause faster recovery of RyRs after a triggered Ca2 + transient, and this would increase the probability that pro-arrhythmic Ca2 + release in the form of regenerative Ca2 + waves could occur during diastole. Subsequent studies documenting Ca2 + waves and increased arrhythmia risk in mice with genetically-modified Casq2 [8], [15] and [16] were consistent with this hypothesis. The present study provides the important additional confirmation that Ca2 + transient restitution is indeed faster in the Casq−/− mice. When considered along with additional recent findings [17] and [18], these studies provide compelling support for the hypothesis that unusually fast Ca2 + release restitution can increase arrhythmia risk.

Kornyeyev et al., however, obtained anadditional interesting result. Upon rapid pacing, the authors found that Casq2−/− mice were less susceptible than Casq2+/+ littermates to T-wave alternans, or beat-to-beat alternation in the amplitude of the ECG T-wave. Such electrical alternanshas been shown in numerous clinical and experimental studies to be a robust indicator of arrhythmia risk (reviewed in [19]). Moreover, electrical alternans is thought to originate with alternans in Ca2 + transient amplitude [20] and [21]. The data of Kornyeyev et al. therefore suggest that Casq2 knockout may predispose hearts to certain types of Ca2 +-dependent arrhythmias while simultaneously protecting hearts against other types of Ca2 +-dependent arrhythmias. Indeed, previous studies, both experimental [22] and theoretical [23], have shown that slow recovery of SR [Ca2 +] can increase the risk of alternans, although in these studies kinetics of SR [Ca2 +] were altered due to changes in the rate of SR Ca2 + uptake rather than changes in buffering. Together, these observations therefore suggest that the “Goldilocks Principle” may apply to Ca2 + release restitution in heart cells: recovery that is either too fast or too slow may be detrimental, whereas a rate of recovery between the potentially dangerous extremes may be ideal.

Clearly additional work must be performed to test this interesting idea. For one thing, it will be important to confirm that altering Ca2 + release restitution affects arrhythmia risk not only in mice, but also in larger animals that bear a greater resemblance to human physiology. It will also be critical to investigate how Ca2 + release restitution is altered not only by Casq2 knockout, but in disease states such as heart failure, where multiple changes that influence Ca2 + release occur. Overall, however, studies such as that of Kornyeyev et al. [7] point to the need for a quantitative rather than simply a qualitative understanding of how perturbations influence cardiac Ca2 + release restitution. To gain such a quantitative understanding and unravel mechanisms, techniques both at the whole heart level and at the level of the Ca2 + spark are likely to be valuable.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors’ laboratories is supported by the National Institutes of Health(and to EAS, and to WJL), the American Heart Association, Heritage Affiliate (10GRNT4170020 to EAS), and the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7), Georg August University, “Identification and therapeutic targeting of common arrhythmia trigger mechanisms” to WJL.

Abbreviations

- [Ca2 +]i

intracellular calcium concentration

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- JSR

junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- CICR

Ca2 +-induced Ca2 + release

- Casq2

type 2 (cardiac) calsequestrin, SR Ca2 + buffer

- CPVT

catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.DelPrincipe F, Egger M, Niggli E. Calcium signalling in cardiac muscle: refractoriness revealed by coherent activation. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:323–9. doi: 10.1038/14013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szentesi P, Pignier C, Egger M, Kranias EG, Niggli E. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ refilling controls recovery from Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release refractoriness in heart muscle. Circ Res. 2004;95:807–13. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146029.80463.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Valdivia HH, Escobar AL, Gyorke S. Luminal Ca2+ controls termination and refractory behavior of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:414–20. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000032490.04207.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Gyorke I, Volpe P, Williams SC, Gyorke S. Calsequestrin determines the functional size and stability of cardiac intracellular calcium stores: mechanism for hereditary arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11759–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932318100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobie EA, Song LS, Lederer WJ. Local recovery of Ca2+ release in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2005;565:441–7. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramay HR, Liu OZ, Sobie EA. Recoveryof cardiac calcium release is controlled by sarcoplasmic reticulum refilling and ryanodine receptor sensitivity. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:598–605. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornyeyev D, Petrosky AD, Zepeda B, Ferreiro M, Knollmann B, Escobar AL. Calsequestrin 2 deletion shortensthe refractoriness of Ca2+ release and reduces ratedependent Ca2+-alternans in intact mouse hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knollmann BC, Chopra N, Hlaing T, Akin B, Yang T, Ettensohn K, et al. Casq2 deletion causes sarcoplasmic reticulum volume increase, premature Ca2+ release, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2510–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI29128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mejia-Alvarez R, Manno C, Villalba-Galea CA, del Valle FL, Costa RR, Fill M, et al. Pulsed local-field fluorescence microscopy: a new approach for measuring cellular signals in the beating heart. Pflugers Arch. 2003;445:747–58. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobie EA, Lederer WJ. Dynamic local changes in sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium: physiological and pathophysiological roles. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06-024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobie EA, Dilly KW, Dos Santos CJ, Lederer WJ, Jafri MS. Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: an investigative mathematical model of calcium-induced calcium release. Biophys J. 2002;83:59–78. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zima AV, Picht E, Bers DM, Blatter LA. Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: role of intra-SR [Ca2+], release flux, and intra-SR Ca2+ diffusion. Circ Res. 2008;103:e105–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.183236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gyorke I, Hester N, Jones LR, Gyorke S. The role of calsequestrin, triadin, andjunction in conferring cardiac ryanodine receptor responsiveness to luminal calcium. Biophys J. 2004;86:2121–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74271-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin J, Valle G, Nani A, Nori A, Rizzi N, Priori SG, et al. Luminal Ca2+ regulation of single cardiac ryanodine receptors: insights providedby calsequestrin and its mutants. J Gen Physiol. 2008;131:325–34. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song L, Alcalai R, Arad M, Wolf CM, Toka O, Conner DA, et al. Calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2) mutations increase expression of calreticulin and ryanodine receptors, causing catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1814–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI31080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzi N, Liu N, Napolitano C, Nori A, Turcato F, Colombi B, et al. Unexpected structural and functional consequences of the R33Q homozygous mutation in cardiac calsequestrin: a complex arrhythmogenic cascade in a knock in mouse model. Circ Res. 2008;103:298–306. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.171660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasserstrom JA, Shiferaw Y, Chen W, Ramakrishna S, Patel H, Kelly JE, et al. Variability in timing of spontaneous calcium release in the intact rat heart is determined by the time course of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium load. Circ Res. 2010;107:1117–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.229294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belevych AE, Terentyev D, Terentyeva R, Nishijima Y, Sridhar A, Hamlin RL, et al. The relationship between arrhythmogenesis and impaired contractility in heart failure: role of altered ryanodine receptor function. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:493–502. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss JN, Nivala M, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. Alternans and arrhythmias: from cell to heart. Circ Res. 2011;108:98–112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pruvot EJ, Katra RP, Rosenbaum DS, Laurita KR. Role of calciumcycling versus restitution in the mechanism of repolarization alternans. Circ Res. 2004;94:1083–90. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125629.72053.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldhaber JI, Xie LH, Duong T, Motter C, Khuu K, Weiss JN. Action potential duration restitution and alternans in rabbit ventricular myocytes: the key role of intracellular calcium cycling. Circ Res. 2005;96:459–66. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156891.66893.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie LH, Sato D, Garfinkel A, Qu Z, Weiss JN. Intracellular Ca alternans: coordinated regulation by sarcoplasmic reticulum release, uptake, and leak. Biophys J. 2008;95:3100–10. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Restrepo JG, Weiss JN, Karma A. Calsequestrin-mediated mechanism for cellular calcium transient alternans. Biophys J. 2008;95:3767–89. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens SC, Terentyev D, Kalyanasundaram A, Periasamy M, Gyorke S. Intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ oscillations are driven by dynamic regulation of ryanodine receptor function by luminal Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2009;587:4863–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domeier TL, Blatter LA, Zima AV. Alteration of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release termination by ryanodine receptor sensitization and in heart failure. J Physiol. 2009;587:5197–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.177576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang SQ, Stern MD, Rios E, Cheng H. The quantal nature of Ca2+ sparks and in situ operation of the ryanodine receptor array in cardiac cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306157101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon TR, Wang F, Puglisi J, Weber C, Bers DM. A mathematical treatment of integrated Ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys J. 2004;87:3351–71. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YS, Keener JP. A calcium-induced calcium release mechanism mediated by calsequestrin. J Theor Biol. 2008;253:668–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang X, Hu XF, Hu J. Dynamic interreceptor coupling contributes to the consistent open duration of ryanodine receptors. Biophys J. 2009;96:4826–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishna A, Sun L, Valderrabano M, Palade PT, Clark JW., Jr Modeling CICR in rat ventricular myocytes: voltage clamp studies. Theor Biol Med Model. 2010;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hashambhoy YL, Greenstein JL, Winslow RL. Role of CaMKII in RyR leak, EC coupling and action potential duration: a computational model. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:617–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rovetti R, Cui X, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Spark-induced sparks as a mechanism of intracellular calcium alternans in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2010;106:1582–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartman JM, Sobie EA, Smith GD. Spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ homeostasis in a minimal model of permeabilized ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1996–2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00293.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaur N, Rudy Y. Multiscale modeling of calcium cycling in cardiac ventricular myocyte: macroscopic consequences of microscopic dyadic function. Biophys J. 2011;100:2904–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams GS, Chikando AC, Tuan HT, Sobie EA, Lederer WJ, Jafri MS. Dynamics of calcium sparks and calcium leak in the heart. Biophys J. 2011;101:1287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]