Abstract

Objectives:

The contribution of acute HIV infection (AHI) to transmission is widely recognized, and increasing AHI diagnosis capacity can enhance HIV prevention through subsequent behavior change or intervention. We examined the impact of targeted pooled nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) and social marketing to increase AHI diagnosis among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Vancouver.

Design:

Observational study.

Methods:

We implemented pooled NAAT following negative third-generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing for males above 18 years in six clinics accessed by MSM, accompanied by two social marketing campaigns developed by a community gay men's health organization. We compared test volume and diagnosis rates for pre-implementation (April 2006–March 2009) and post-implementation (April 2009–March 2012) periods. After implementation, we used linear regression to examine quarterly trends and calculated diagnostic yield.

Results:

After implementation, the AHI diagnosis rate significantly increased from 1.03 to 1.84 per 1000 tests, as did quarterly HIV test volumes and acute to non-acute diagnosis ratio. Of the 217 new HIV diagnoses after implementation, 54 (24.9%) were AHIs (25 detected by pooled NAAT only) for an increased diagnostic yield of 11.5%. The average number of prior negative HIV tests (past 2 years) increased significantly for newly diagnosed MSM at the six study clinics compared to other newly diagnosed MSM in British Columbia, per quarter.

Conclusion:

Targeted implementation of pooled NAAT at clinics accessed by MSM is effective in increasing AHI diagnoses compared to third-generation EIA testing. Social marketing campaigns accompanying pooled NAAT implementation may contribute to increasing AHI diagnoses and frequency of HIV testing.

Keywords: acute disease, HIV infections, homosexuality, male, nucleic acid amplification techniques, public health, social marketing

Introduction

During acute HIV infection (AHI), there is a high risk of secondary transmission due to significantly elevated HIV viral load and viral homogeneity [1]. Individuals with AHI are likely to be part of active sexual networks and to transmit to others through ongoing participation in these networks [2]. The contribution of individuals with AHI to onward transmission is well acknowledged, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) [3,4]. Although estimates vary, the contribution may be as high as 50% of incident infections [1,5,6]. When individuals with HIV infection are informed of their diagnosis, behavior change typically occurs, which reduces the risk of transmission to others [7–10]. Additional interventions to enhance the prevention of HIV transmission (e.g. partner counseling and referral, behavior change interventions, and early antiretroviral treatment) for those diagnosed with AHI may augment the public health benefit of informing persons of their acute HIV status [11,12].

Currently available third-generation antibody-based HIV tests can identify people with AHI [13], and may be superior to rapid/point-of-care HIV tests [14]. Pooled nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) can detect HIV infection within 7–15 days following infection (vs. 20–30 days for third-generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing) [15]. The implementation of pooled NAAT for HIV detection has been shown to increase the diagnostic yield of HIV testing algorithms by 0.1–23%, depending on the population tested, the generation of screening EIA test used [16], and the specimen pooling schemes utilized [17]. Targeted implementation of pooled NAAT for populations with a higher risk of infection maximizes the detection of AHI [18–20] and may be more cost-effective [21].

MSM, in particular, may benefit from pooled NAAT in British Columbia, as MSM comprise the majority of new HIV infections; in 2011, 58% of new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia occurred among MSM (78% of which were in the Vancouver region) [22]. Despite a decrease in new HIV diagnoses overall in British Columbia, attributed to expanded coverage of HAART, this benefit has not extended to MSM [22,23]. In British Columbia, AHIs diagnosed using standard HIV-screening protocols are more likely to be MSM than non-MSM [13].

In this study, we describe the impact of targeted NAAT on the identification of AHI and discuss the potential of social marketing campaigns to optimize targeted AHI detection among MSM in Vancouver.

Methods

Selection of sites

Potential clinic sites with high HIV-detection rates in MSM were identified through review of provincial HIV surveillance data and consultation with clinicians. Pooled NAAT was implemented at five clinics starting in April 2009 and a sixth community clinic in September 2009.

Laboratory methods

All testing was conducted at the British Columbia Public Health Microbiology and Reference Laboratory (BCPHMRL). Prior to April 2009, the standard provincial algorithm for all specimens was initial screening by third-generation EIA (ADVIA Centaur HIV-1/0/2; Siemens, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and if reactive, testing by Western Blot (Genetic Systems HIV-1 Western Blot; BioRad, Montreal Quebec, Canada). Specimens that were EIA-reactive with Western Blot-negative or indeterminate results were further tested for p24 antigen (Vironostika HIV-1 Antigen; Biomerieux, St-Laurent, Quebec, Canada) or by HIV NAAT (AMPLICOR HIV-1 DNA Test, v1.5; Roche, Laval, Quebec, Canada) [13].

Beginning in April 2009, all specimens submitted for HIV testing from study clinics, where sex was listed as male, transgendered or missing and age was above 18 years were entered into the study testing algorithm. This algorithm diverged from the above protocol in that third-generation EIA-reactive, Western Blot-negative or indeterminate specimens were subjected to an individual HIV-1 NAAT (COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test, v1; Roche). If non-reactive on third-generation EIA, eligible specimens (100 μl/specimen) were combined into pools and tested by HIV-1 NAAT (COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test, v1; Roche), with positive pools deconstructed to identify the positive specimen.

Case definitions

Acute HIV infection cases met the following criteria: detection of HIV RNA or DNA by NAAT (before and after April 2009) or detection of p24 antigen with confirmation by neutralization assay (before April 2009), in the absence of confirmed detection of HIV antibody via Western Blot and absence of an AIDS case report before or up to 12 months after diagnosis (to exclude the possibility of reduced antibody response associated with advanced disease). AHI cases during the post-pooling period were classified as those detected through the pooled NAAT algorithm only, or through the standard testing algorithm.

Analysis

HIV testing data were extracted from the BCPHMRL database, and linked probabilistically to the provincial HIV surveillance database to identify confirmed HIV diagnoses. We compared equivalent 36-month pre-pooling (April 2006 to March 2009) and post-pooling (April 2009 to March 2012) periods, using data from the five study clinics in operation during both the pre and post-intervention periods. We compared using Pearson's chi-square tests the number of unique individuals tested, number of individuals diagnosed with HIV (acute and non-acute), and rate of diagnosis per 1000 persons tested.

For the post-intervention period, we used data from all six study clinics to calculate diagnostic yield and determine total acute and non-acute HIV diagnosis rates and ratio by quarter. To examine changes in test frequency, we calculated quarterly trends for the average number of prior negative HIV tests in the past 2 years for newly diagnosed MSM in British Columbia, diagnosed at study clinics and other sites. We used linear regression to assess the significance of all quarterly trends (level of significance for all analyses set at P < 0.05).

Social marketing campaigns

Two campaigns were implemented during the study period: What Are You Waiting For (WRUW4; December 2009 to February 2010) and Hottest At The Start (HATS; June to August 2011). WRUW4 focused on raising awareness of new test technologies (rapid testing and NAAT), whereas HATS was specifically directed towards gay men engaging in risky sex or initiating new relationships, and focused on raising awareness of AHI and increased transmission risk. Promotional strategies for both campaigns included posters, post cards, urinal ads, and condom packs at a variety of gay venues, as well as e-mail blasts and campaign websites [24,25].

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board.

Results

The rate of AHI diagnoses increased in the post-implementation period (from 1.03 to 1.84 per 1000 men tested; P = 0.003) despite an overall decrease in total new HIV diagnoses (Table 1). When considering all six study clinics, of 217 new HIV diagnoses during the post-implementation period, 54 (24.9%) were AHI and 208 (96%) identified as MSM. Twenty-five (46%) of the 54 AHI diagnoses were non-reactive on third-generation EIA testing, hence the addition of pooled NAAT resulted in an 11.5% (25/217) increase in diagnostic yield. The addition of the sixth study clinic, a high-profile community sexual health clinic located in a community gay men's health agency, had a large impact, accounting for 31% of all AHI diagnoses detected at study clinics (with a total and acute HIV diagnosis rate of 22.5 and 9.5 per 1000 tests, respectively).

Table 1.

Comparison of total and AHI diagnosis rates at study clinics before and after implementation of pooled NAAT.

| Individuals | Study clinics with data for pre and post-intervention* periods (n = 5) | All study clinics (n = 6) | ||||

| Pre-intervention (April 2006–March 2009) | Post-intervention (April 2009–March 2012) | Post-intervention (April 2009–March 2012) | ||||

| Number | Rate/1000 tests | Number | Rate/1000 tests | Number | Rate/1000 tested | |

| Tested | 18 393 | – | 20 141 | – | 21 967 | – |

| Diagnosed with HIV (total) | 218 | 11.85 | 176 | 8.74a | 217 | 9.88 |

| Diagnosed with acute HIV | 19 | 1.03 | 37 | 1.84b | 54 | 2.46 |

AHI, acute HIV infection; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification testing. Explanatory footnote: Analysis based on individuals identified as male, transgender, or unknown sex, of age at least 19 years.

aChi-square (P = 0.003).

bChi-square (P = 0.053).

*One study clinic started operation in the post-intervention period and had no historic data.

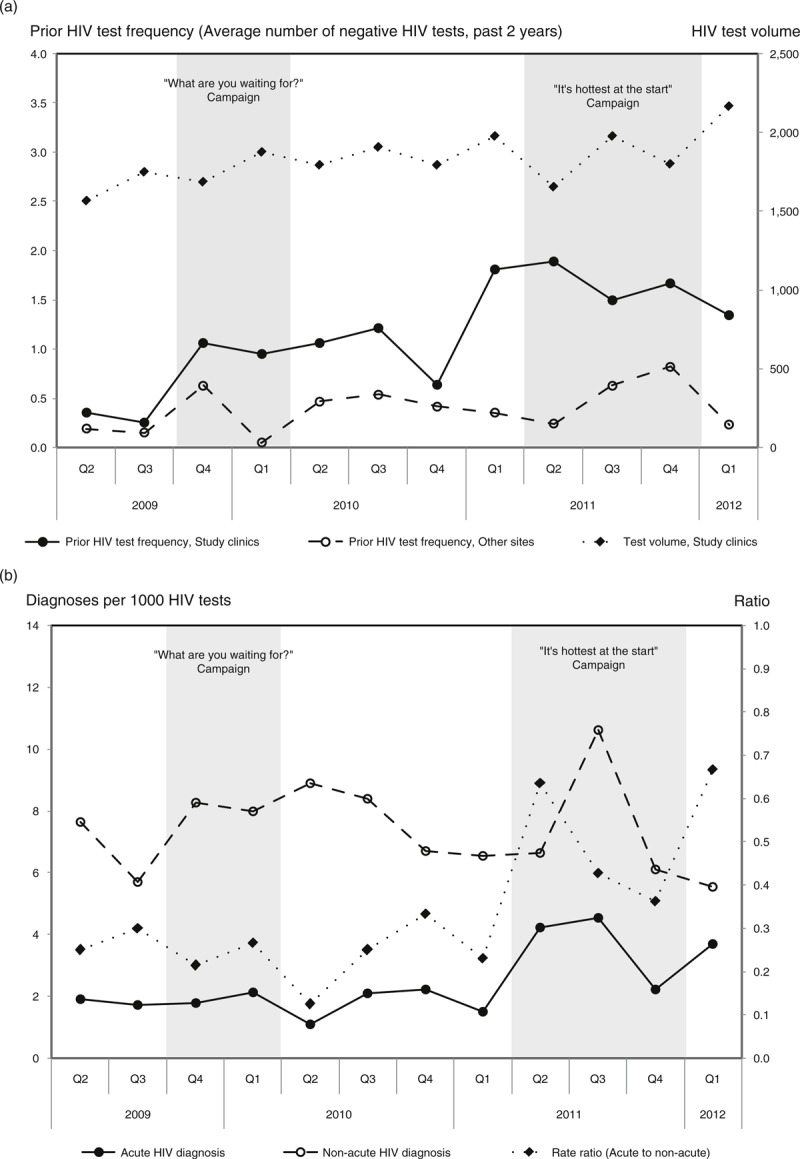

The volume of HIV tests at study clinics increased over the post-implementation period (P = 0.023; Fig. 1a). Prior HIV test frequency significantly increased over time (P = 0.002) and was higher at study clinics compared to other sites (P < 0.001). We observed an increase in both acute and non-acute HIV diagnosis rates and in increase in the acute to non-acute rate ratio (P = 0.015) at study sites with the second social marketing campaign (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Test volume, prior HIV test frequency, and diagnosis rates after implementation of pooled nucleic acid amplification testing and social marketing campaigns, April 2009 to March 2012.

(a) Total HIV test volume (study clinics) and prior HIV test frequency among newly diagnosed MSM (at study clinics compared to other sites in British Columbia). (b) Acute and non-acute HIV diagnosis rate at study clinics. Explanatory footnote: Test volume and diagnosis rates based on individuals identified as male, transgender, or unknown sex, of age at least 19 years. Prior HIV test frequency calculated as the average number of HIV tests in the past 2 years for newly diagnosed MSM per quarter.

Discussion

Our data suggest that the targeted implementation of pooled NAAT and social marketing has significantly improved detection of AHI among MSM at clinic sites with pre-existing high HIV detection rates. This targeted approach was effective; after implementation, these study clinics represented 4% of all HIV tests performed by BCPHMRL, yet accounted for 24% of HIV diagnoses and 59% of all AHI cases in British Columbia.

Whereas other studies comparing pooled NAAT to earlier-generation tests (with longer window periods) have shown similar or higher results, our 11.5% increase in detection yield was substantially higher than other studies comparing pooled NAAT to third-generation EIA. One large study involving multiple testing sites in three US states found increased detection yields of between 1.4 and 5.9% (and an overall prevalence of AHI of 0.3 per 1000 persons tested) [26]. A second study in STD clinics in Baltimore demonstrated a 0.6% increase in detection yield (overall AHI prevalence 0.19 per 1000 persons tested) [27]. There are several possible explanations for our much higher yield and greater AHI prevalence, including the higher proportion of MSM in our study.

We also postulate that two social marketing campaigns (executed by the gay men's health agency, which also operates the community study clinic) contributed to our high diagnostic yield. We observed a significantly greater increase in prior HIV test frequency among newly diagnosed MSM at study clinics compared to other sites, and an increase both in acute and non-acute HIV diagnosis rates and the ratio of acute to non-acute HIV diagnoses with the second social marketing campaign. Whereas as a result of joint implementation we cannot distinguish the effects of pooled NAAT from social marketing, it is unlikely that these findings would be explained solely by the implementation of the pooled NAAT laboratory algorithm. We speculate that these social marketing campaigns may have increased awareness of the availability of AHI testing and recommendations to test soon after a potential exposure or new relationship, and led to greater frequency of testing and a shift towards earlier diagnosis among MSM attending the study clinics.

Formal evaluations of the impact of social marketing campaigns on detection of AHI are scarce. A New York City campaign designed to increase awareness of seroconversion symptoms and encourage testing among MSM led to an AHI detection rate of 2.8% among 497 persons testing through the campaign [28]. More recently, a Seattle evaluation of the ‘ru2hot’ campaign found that although the campaign was successful in increasing awareness among MSM, there was no detectable impact on case-finding [29]. Our findings suggest a positive impact of social marketing, which may be related both to the sustained nature of the social marketing, and our emphasis on the nature of AHI and promoting availability of an ‘early test’ soon after a potential exposure (rather than on seroconversion symptoms).

Finally, if pooled NAAT had not been in place, 46% of men with AHI would have been given a negative test result. It is estimated that a diagnosis of AHI may result in the prevention of between one and three additional infections in the year following diagnosis compared to diagnosis of established HIV due to high viral load and continued risk behaviors [30,31]. Conservatively, one may then estimate that the early diagnosis of 25 men in our study potentially avoided 25 new cases of HIV among MSM in Vancouver.

In summary, our findings confirm that introduction of pooled NAAT in targeted clinical settings with high HIV diagnosis rates is effective at increasing diagnostic yield [32] and suggests that the implementation of AHI social marketing campaigns may promote earlier diagnosis and more frequent HIV testing. With the advent of fourth-generation immunoassay testing, which has a shorter window period than third-generation tests (15–20 days) [15,33], it is important to consider whether pooled NAAT will remain a cost-effective option for detection of AHI in targeted settings [31,34].

Acknowledgements

M.G. led and D.C., M.S., M.Kw., M.Kr., and M.R. contributed to the conceptualization and design and of the study. D.C. and M.Kr. led the implementation of the laboratory protocol and M.G. conducted the analysis of laboratory data. W.R., G.D., M.Kw., and M.S. contributed to the clinical implementation of the study, and design and implementation of social marketing campaigns. All authors contributed to the interpretation of findings. M.G. led the development of the manuscript to which all authors contributed.

The authors wish to acknowledge the important contributions of all study members and community partners of the CIHR Study of Acute HIV infection in Gay Men to this work. We also acknowledge the important contributions of Wendy Mei, Annie Mak and colleagues in the BCPHMRL in testing the specimens and generating data used in this study; Stanley Wong, Amanda Yu, Theodora Consolacion and Travis Salway Hottes from BCCDC who assisted in data extraction and analysis; and Kate Heath for her assistance with manuscript preparation. Finally, we acknowledge the support of the Public Health Agency of Canada and the STOP HIV/AIDS Pilot project in providing programmatic funds to support the implementation of pooled NAAT used for this study.

Source of funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant No. HET 85520.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Correspondence to Dr Mark Gilbert, MD, Clinical Prevention Services, BC Centre for Disease Control, 655 West 12th Avenue, Vancouver, BC V5Z 4R4, Canada. Tel: +1 604 707 5615; fax: +1 604 707 5604; e-mail: mark.gilbert@bccdc.ca

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Shaw GM, McMichael AJ, Haynes BF. Acute HIV-1 Infection. New Engl J Med 2011; 364:1943–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koopman JS, Jacquez JA, Welch GW, Simon CP, Foxman B, Pollock SM, et al. The role of early HIV infection in the spread of HIV through populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1997; 14:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chibo D, Kaye M, Birch C. HIV transmissions during seroconversion contribute significantly to new infections in men who have sex with men in Australia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012; 28:460–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frange P, Meyer L, Deveau C, Tran L, Goujard C, Ghosn J, et al. Recent HIV-1 infection contributes to the viral diffusion over the French territory with a recent increasing frequency. PLoS One 2012; 7:e31695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy J-P, Moisi D, Ntemgwa M, Matte C, et al. High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:951–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powers KA, Ghani AC, Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Pettifor AE, Kamanga G, et al. The role of acute and early HIV infection in the spread of HIV and implications for transmission prevention strategies in Lilongwe, Malawi: a modelling study. Lancet 2011; 378:256–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 39:446–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Jeffries R, Javanbakht M, Drumright LN, Daar ES, et al. Behaviors of recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men in the year postdiagnosis: effects of drug use and partner types. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011; 56:176–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steward WT, Remien RH, Higgins JA, Dubrow R, Pinkerton SD, Sikkema KJ, et al. Behavior change following diagnosis with acute/early HIV infection-a move to serosorting with other HIV-infected individuals. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: III. AIDS Behav 2009; 13:1054–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox J, White PJ, Macdonald N, Weber J, McClure M, Fidler S, et al. Reductions in HIV transmission risk behaviour following diagnosis of primary HIV infection: a cohort of high-risk men who have sex with men. HIV Med 2009; 10:432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, Foust E, Wolf L, Williams D, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1873–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilcher CD, Christopoulos KA, Golden M. Public health rationale for rapid nucleic acid or p24 antigen tests for HIV. J Infect Dis 2010; 201 Suppl 1:S7–S15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg M, Cook DA, Gilbert M, Krajden M, Haag D, Tsang P, et al. Towards targeted screening for acute HIV infections in British Columbia. J Int AIDS Soc 2011; 14:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook D, Gilbert M, DiFrancesco L, Krajden M. Detection of early sero-conversion HIV infection using the INSTI HIV-1 antibody point-of-care test. Open AIDS J 2010; 4:176–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Branson BM, Stekler JD. Detection of acute HIV infection: we can’t close the window. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:521–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yerly S, Hirschel B. Diagnosing acute HIV infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2012; 10:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherlock M, Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Routine detection of acute HIV infection through RNA pooling: survey of current practice in the United States. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34:314–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Facente SN, Pilcher CD, Hartogensis WE, Klausner JD, Philip SS, Louie B, et al. Performance of risk-based criteria for targeting acute HIV screening in San Francisco. PLoS One 2011; 6:e21813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller WC, Leone PA, McCoy S, Nguyen TQ, Williams DE, Pilcher CD. Targeted testing for acute HIV infection in North Carolina. AIDS 2009; 23:835–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powers KA, Miller WC, Pilcher CD, Mapanje C, Martinson FEA, Fiscus SA, et al. Improved detection of acute HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa: development of a risk score algorithm. AIDS 2007; 21:2237–2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutchinson AB, Patel P, Sansom SL, Farnham PG, Sullivan TJ, Bennett B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pooled nucleic acid amplification testing for acute HIV infection after third-generation HIV antibody screening and rapid testing in the United States: a comparison of three public health settings. PLoS Med 2010; 7:e1000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HIV in British Columbia Annual Surveillance Report 2011. BC Centre for Disease Control, Provincial Health Services Authority; 2012. 45 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montaner JSG, Lima VD, Barrios R, Yip B, Wood E, Kerr T, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy converage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet 2010; 376:532–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.What Are You Waiting For? [Internet]. Vancouver (BC): Health Initiative for Men; [cited 2013 Aug 6] Available from: http://www.whatruwaiting4.ca/Home.html [Google Scholar]

- 25.HIV: It's Hottest at the Start [Internet]. Vancouver (BC): Health Initiative for Men; [cited 2013 Aug 6] Available from: http://checkhimout.ca/hottest/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel P, Mackellar D, Simmons P, Uniyal A, Gallagher K, Bennett B, et al. Detecting acute human immunodeficiency virus infection using 3 different screening immunoassays and nucleic acid amplification testing for human immunodeficiency virus RNA, 2006–2008. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170:66–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Temkin E, Marsiglia VC, Hague C, Erbelding E. Screening for acute human immunodeficiency virus infection in Baltimore public testing sites. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:374–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silvera R, Stein D, Hutt R, Hagerty R, Daskalakis D, Valentine F, et al. The development and implementation of an outreach program to identify acute and recent HIV infections in New York City. Open AIDS J 2010; 4:76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stekler JD, Baldwin HD, Louella MW, Katz DA, Golden MR. ru2hot?: a public health education campaign for men who have sex with men to increase awareness of symptoms of acute HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89:409–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han X, Xu J, Chu Z, Dai D, Lu C, Wang X, et al. Screening acute HIV infections among Chinese men who have sex with men from voluntary counseling and testing centers. PLoS One 2011; 6:e28792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karris MY, Anderson CM, Morris SR, Smith DM, Little SJ. Cost savings associated with testing of antibodies, antigens, and nucleic acids for diagnosis of acute HIV infection. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:1874–1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Dragavon J, Thomas KK, Brennan CA, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough?. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:444–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark JL, Segura ER, Montano SM, Leon SR, Kochel T, Salvatierra HJ, et al. Routine laboratory screening for acute and recent HIV infection in Lima, Peru. Sex Transm Infect 2010; 86:545–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long EF. HIV screening via fourth-generation immunoassay or nucleic acid amplification test in the United States: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS One 2011; 6:e27625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]