Abstract

Podocytes represent an essential component of the kidney’s glomerular filtration barrier. They stay attached to the glomerular basement membrane via integrin interactions that support the capillary wall to withstand the pulsating filtration pressure. Podocyte structure is maintained by a dynamic actin cytoskeleton. Terminal differentiation is coupled with permanent exit from the cell cycle and arrest in a postmitotic state. Postmitotic podocytes do not have an infinite life span; in fact, physiologic loss in the urine is documented. Proteinuria and other injuries accelerate podocyte loss or induce death. Mature podocytes are unable to replicate and maintain their actin cytoskeleton simultaneously. By the end of mitosis, cytoskeletal actin forms part of the contractile ring, rendering a round shape to podocytes. Therefore, when podocyte mitosis is attempted, it may lead to aberrant mitosis (ie, mitotic catastrophe). Mitotic catastrophe implies that mitotic podocytes eventually detach or die; this is a previously unrecognized form of podocyte loss and a compensatory mechanism for podocyte hypertrophy that relies on post–G1-phase cell cycle arrest. In contrast, local podocyte progenitors (parietal epithelial cells) exhibit a simple actin cytoskeleton structure and can easily undergo mitosis, supporting podocyte regeneration. In this review we provide an appraisal of the in situ pathology of mitotic catastrophe compared with other proposed types of podocyte death and put experimental and renal biopsy data in a unified perspective.

CME Accreditation Statement: This activity (“ASIP 2013 AJP CME Program in Pathogenesis”) has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of the American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) and the American Society for Investigative Pathology (ASIP). ASCP is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

The ASCP designates this journal-based CME activity (“ASIP 2013 AJP CME Program in Pathogenesis”) for a maximum of 48 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

CME Disclosures: The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose.

Podocyte injury is a key manifestation of proteinuric glomerulopathies, for example, minimal change disease (MCD), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and diabetic nephropathy. Normal podocytes are postmitotic cells composed of a voluminous cell body with a single well-formed nucleus and primary and secondary foot processes attached to adjacent capillary loops in an interdigitating manner. Injured podocytes invariably respond with foot process effacement, a frequently reversible process, thought to help injured podocytes stay attached to the glomerular basement membrane (GBM).1 Sustained podocyte injury, however, is likely to cause podocyte cell detachment and/or death, which, if extensive, leads to progressive glomerulosclerosis and end-stage kidney disease.2 The mechanisms of podocyte loss could be important in three ways: first, as a pathophysiologic determinant of progressive chronic kidney disease; second, as a potentially significant histopathologic prognostic parameter; and third, as a target for novel therapies to prevent progressive glomerulosclerosis.

Currently, podocyte assessment in human disease is often limited to the ultrastructural appearance of the secondary foot processes, which normally appear as teethlike, interdigitating, and slit-membrane–forming processes, whereas damaged foot processes appear flat (effaced) under transmission electron microscopy (EM). The specific podocyte death morphology is not currently routinely assessed in renal biopsy specimens or for diagnostic or glomerular disease risk assessment. Approximately one dozen mechanisms of cell death are described, mostly in vitro and in vivo models, suggesting numerous avenues for podocyte loss (Table 1).14,15 These mechanisms include apoptosis (physiologic cell death implicated in organogenesis and, if defective, in disease pathogenesis), anoikis (cell death due to absence of cell-matrix interactions implicated in cancer metastasis), autophagy (starvation-induced cell death), entosis (cell-in-cell death, cannibalism), necrosis (unregulated lysis of cell membrane), necroptosis (specifically regulated-programmed necrosis), mitotic catastrophe (MC; cell death due to aberrant mitosis), and others.14–16 The gold standard for detecting some forms of cell death, for example, apoptosis, necrosis, or MC, remains the nuclear pathologic feature viewed with EM.1 Podocyte maturation and apoptosis were studied in experimental animals. Defective apoptosis is thought to play a role in certain types of nephrotic syndrome, but little is known about podocyte cell death and its significance in human podocyte disease.15–18 Several studies recently suggested that MC represents a previously unrecognized cause of podocyte loss in experimental models of glomerular and human disorders.3,4,19 This review is a critical appraisal of i) the current views on how the podocyte cell proliferation machinery (cell cycle) responds to injury, potentially leading to podocyte cell death; ii) the possible mechanisms podocytes use in an attempt to avoid death after injury; and iii) the in situ morphology of podocyte cell death in human disease with emphasis on MC.

Table 1.

Mitotic Catastrophe and Other Types of Podocyte Death in Human and Experimental Glomerular Disease

| Cell death type | Definition | Morphologic features | Disease | Experimental glomerular disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitotic catastrophe | Aberrant mitosis | Binucleation, micronuclei, aberrant mitotic spindles | HIVAN, FSGS, MCD, IgA, other | Adriamycin nephropathy | 3,4 |

| Apoptosis | Nuclear death | Nuclear condensation, blebbing, nuclear fragmentation, apoptotic bodies | Uncertain | TGF-β overexpression in cultured podocytes | 5–12 |

| Autophagy | Nutrient starvation–induced death | Autophagosomes, autophagolysosomes (transient vacuoles and RER stress) | Lysosomal storage diseases | Puromycin aminonucleoside-induced nephrosis | 13 |

| Anoikis | Absence of cell-matrix interactions | Apoptosis induced by lack of correct cell/ECM attachment | Unknown | ||

| Entosis | Cell cannibalism | Cell–in cell | Unknown | ||

| Necrosis | Cell lysis | Early: cytoplasmic and nuclear edema late: plasma membrane rupture nuclear and cytoplasmic disintegration | Toxic-ischemic and necrotizing glomerular injury | ||

| Necroptosis | Regulated necrosis | Cell membrane rupture, oncosis, but no nuclear fragmentation into apoptotic bodies | Unknown |

ECM, extracellular matrix; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β.

Cell Cycle from the Podocyte’s Perspective

Mature podocytes are thought to be quiescent cells arrested in the G0 (resting) phase. Cell cycle entry involves the G1 (gap) phase, during which cells synthesize RNA, protein, and organelles; the S phase, during which DNA is duplicated and cells increase in size; and the M phase (for mitosis), when DNA and protein synthesis stops and the cell divides. Cell mitosis includes a series of sequential events referred to as interphase, prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, telophase, and cytokinesis, which describe the different stages of nuclear membrane disintegration, mitotic spindle formation, chromatin assembly into chromosomes, chromosome segregation, nuclear membrane formation, and cytoplasmic division. Normal cell cycle functions are accomplished through activation of CDKs and specific cyclins (eg, CDK1). These phosphorylate a variety of proteins that control the cell cycle.20,21 Important regulators of the cell cycle are the p53 and p27 proteins, which can block the cell cycle at distinct restriction points. For example, in the case of DNA damage the cell activates the DNA repair machinery before completing the cell cycle. If DNA damage is severe, p53 is activated, leading to cell death to make sure that cells with significant DNA damage are deleted.

Chromosome segregation depends on structural proteins and cell cycle regulatory complexes. Podocytes express cyclin A, B1, and D1 and CDK inhibitors, such as p21, p27, and p57. Ki-67, a marker of G1, S, G2, and M phase, is amply expressed in podocyte precursors, but at the capillary loop stage, cell cycle proteins and CDKs are altered; for example, Ki-67, cyclin A, and cyclin B1 are reduced, and CDKs and cyclin D1 are increased. These changes are associated with podocyte exit from the cell cycle and are concurrent with the formation of podocyte foot processes and expression of podocyte-specific proteins, such as podocalyxin and WT-1 characteristic of differentiated podocytes.22,23 Mature podocytes are indeed sustained by specific CDK inhibitor up-regulation, which guarantees their highly specialized structure and function.19

Cyclins and CDKs are altered in human and experimental podocyte injury. For example, in the cellular type of human FSGS, studies have found absent p27, p57, and cyclin D1 expression and increased cyclin E, cyclin A, cyclin B1, CDK2, and p21.24 In experimental Adriamycin-induced FSGS, the CDK inhibitor p21 is increased and found to protect podocytes in this model.25 In other glomerular diseases, such as membranous glomerulopathy, podocytes demonstrate DNA synthesis but no podocyte proliferation. Studies in experimental membranous nephropathy report that Cdc2, cyclin B1, and cyclin B2 are increased in rat podocytes despite absent proliferation.26 The results suggest that increased expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins is not sufficient for podocyte proliferation and that other factors appear to be involved. In diabetes, a disease characterized by podocyte hypertrophy, glomerular p21 is increased in the streptozotocin-induced mouse model, and p21 and p27 are increased in the glomeruli of diabetic db/db mice and Zucker diabetic rats that develop type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Diabetic p21−/− mice are protected from glomerular hypertrophy. p21−/− mice develop glomerular hyperplasia rather than hypertrophy, and progressive renal failure is halted.27

In each phase of the cell cycle, the nucleus has characteristic morphologic features, for example, in interphase when the DNA is copied, the nucleus is visible, but chromosomes are invisible.28 Micronuclei can also be present during interphase; they are rounded DNA aggregates that represent genomic instability and typically appear adjacent to the nucleus with a diameter not larger than one-third of the nucleus. In anaphase the mitotic spindle is visible, and new nuclear membrane forms around the sister chromatids; finally, the cytoplasm divides into two identical daughter cells by cytokinesis in all cell types except for highly specialized postmitotic cells, including podocytes. Indeed, because differentiated podocytes have an intrinsic barrier to mitosis, a proliferative response of surviving podocytes instead of contributing to recovery from injury may accelerate podocyte loss and glomerulosclerosis. However, we have previously reported that podocyte progenitors exist in the glomerulus that can complete the cell cycle to potentially regenerate lost podocytes.

Parietal Epithelial Cells: Podocyte Progenitors That Can Proliferate

Recently, it was demonstrated that a population of progenitor cells in the parietal epithelium of the Bowman capsule of adult human kidney acts as a source of intrarenal progenitors for visceral podocytes.29–32 These cells exhibit a mixed phenotype between parietal epithelial cells and podocytes and can proliferate and differentiate generating neopodocytes during development and in postnatal and adolescent mice.32,33 These cells have the potential to become podocytes without yet displaying the complex cytoskeletal structure that prohibits an efficient mitotic division (Figure 1). Indeed, during development, podocyte progenitors up-regulate podocyte-specific genes and show de novo expression of the CDK inhibitor p27; at the same time PAX2 is down-regulated as progenitors differentiate into podocytes.34 The down-regulation of PAX2 by WT1 seems to be a prerequisite for WT1-controlled differentiation35 through inhibition of β-catenin/Wnt signaling.36 Interestingly, the β-catenin/Wnt signaling is also a direct activator of cyclin D1, a critical initiator of cell division that controls podocyte progenitor proliferation during development and postnatally, maintaining their capacity to divide while they are in an undifferentiated state.36,37 Podocyte progenitors exhibit a simple cytoskeleton and a high proliferative capacity, which disappears once the highly specialized podocyte phenotype is acquired. Notch activation triggers proliferation of podocyte progenitors by promoting entry into the S-phase and mitotic division.19 However, attenuation of Notch activity is required to allow podocyte progenitors to differentiate into visceral podocytes, as demonstrated by abnormal DNA content and podocyte death by MC after impaired down-regulation of the Notch pathway.19

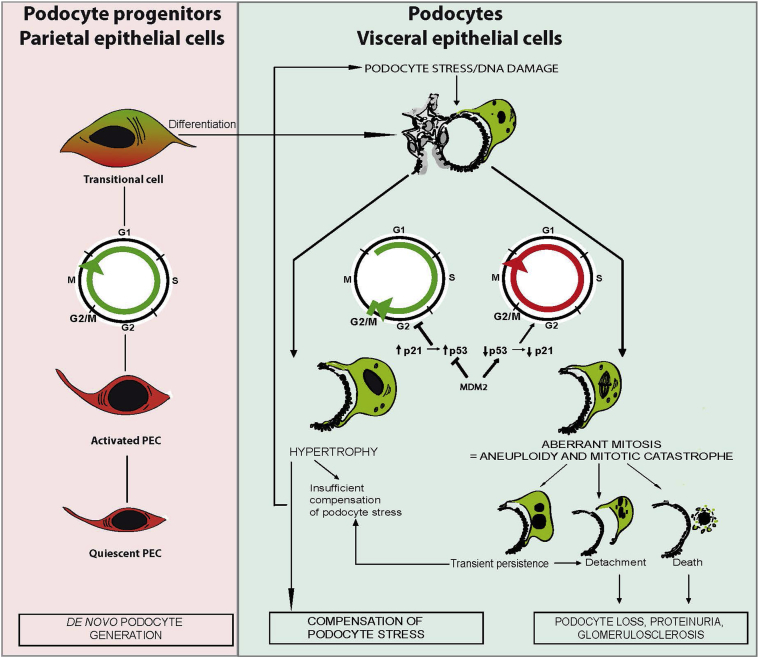

Figure 1.

Working model of the role of cell cycle in proliferation of podocyte progenitor cells or podocyte hypertrophy and how aberrant podocyte proliferation may lead to podocyte loss. De novo podocyte generation starts from renal progenitors that are committed to the podocyte lineage within the parietal epithelial cell (PEC) layer. On activation, PECs enter the cell cycle (ie, proliferate and differentiate), which first creates a transitional cell that expresses both PEC and podocyte markers. Transitional cells are often found around the vascular pole of the glomerulus. Terminal differentiation into podocytes usually occurs only on the glomerular tuft, which implies loss of all parietal cell and progenitor markers so that these cells can no longer be distinguished from podocytes. Only parietal cell lineage tracing experiments are able to document that these are a progeny of former parietal epithelial cells. Once terminally differentiated (and postmitotic) podocytes are exposed to stress, such as loss of neighboring podocytes, a compensatory response becomes necessary. Functionally and structurally, the most important response to stress is podocyte hypertrophy. To undergo hypertrophy the podocyte needs to enter the S phase of the cell cycle but keep the cell cycle arrest at the G1 or G2/M restriction point. This is ensured by p53-mediated induction of cyclin kinases, such as p21. Mitogenic stimuli or DNA damage induce MDM2, which inactivates p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and forces the podocytes to complete mitosis. However, podocytes need their actin cytoskeleton to maintain their sophisticated anatomical structure; therefore, this usually leads to an incomplete formation of mitotic spindles, aberrant chromosome segregation, and/or podocyte detachment. In addition, podocytes cannot complete cytokinesis, which results in aneuploid podocytes with two or more nuclei. Such cells are susceptible to death; hence, podocyte mitosis is not a sign of podocyte regeneration but a pathologic mechanism of podocyte loss.

The discovery that parietal epithelial cells represent podocyte progenitors and can potentially differentiate into podocytes provides an explanation of how podocyte regeneration can be achieved even if differentiated podocytes are virtually unable to divide successfully. Several reports indicate that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, retinoids, and steroids enhance the capacity of podocyte progenitors to become podocytes.38–41 In addition, podocyte regeneration can be modulated using Notch inhibitors in mouse models of FSGS, directly influencing the amount of proteinuria and the occurrence of glomerulosclerosis.19 Finally, recent studies suggest that blockade of SDF-1/CXCL12 also increases the number of podocytes and reduces proteinuria in type 2 diabetic mice by enhancing parietal epithelial cell differentiation toward the podocyte phenotype,42,43 suggesting that pharmacologic treatments can modulate podocyte progenitor proliferation and/or differentiation into podocytes.

Stressed Podocytes Reenter the Cell Cycle and Undergo Hypertrophy but Fall Short of Mitosis

Hypertrophy (increase in cell size) and hyperplasia (increase in cell number) are two cellular strategies to compensate for cell stress or relative cytopenia (eg, during organogenesis or injury). Hypertrophy and hyperplasia both imply that quiescent cells reenter the G1 phase to increase the amount of cell organelles and proteins. Although glomerular endothelial cells and mesangial cells easily proliferate, podocytes undergo hypertrophy, producing additional foot processes to compensate for podocytopenia.2,44 But how do podocytes undergo hypertrophy versus hyperplasia? The cell cycle can be arrested in the G1 and G2 phases, at so-called restriction points, which prevent podocyte progression to mitosis. Not only is this fundamental control mechanism required for cell hypertrophy, it also prevents aberrant mitosis of cells with significant DNA damage (Figure 1). However, if a cell with defective DNA enters mitosis prematurely, before DNA damage is repaired or before DNA replication is complete, the subsequent aberrant mitosis leads to asymmetric chromosomal division and formation of severely damaged cells, prone to develop cancer. Most commonly, however, aberrant mitosis leads to cell death (ie, MC), a safeguard mechanism to prevent cancer. Podocytes are not known to form cancers, which supports the concept that podocytes with significant DNA damage cannot survive mitosis and, if forced to override these cell cycle restriction points, detach and are lost in the urine. Mitotic podocytes detach also because actin assembly for forming the mitotic spindle is no longer compatible with maintaining the cytoskeletal structure of secondary foot processes.45 Therefore, podocytes may express cell cycle markers (such as Ki-67) when they undergo hypertrophy, but they are unlikely to undergo mitosis (ie, display nuclei in pro-, prometa-, meta-, ana-, or telophase). Podocytes with mitotic figures are indeed susceptible to detachment and/or death (Figure 2).

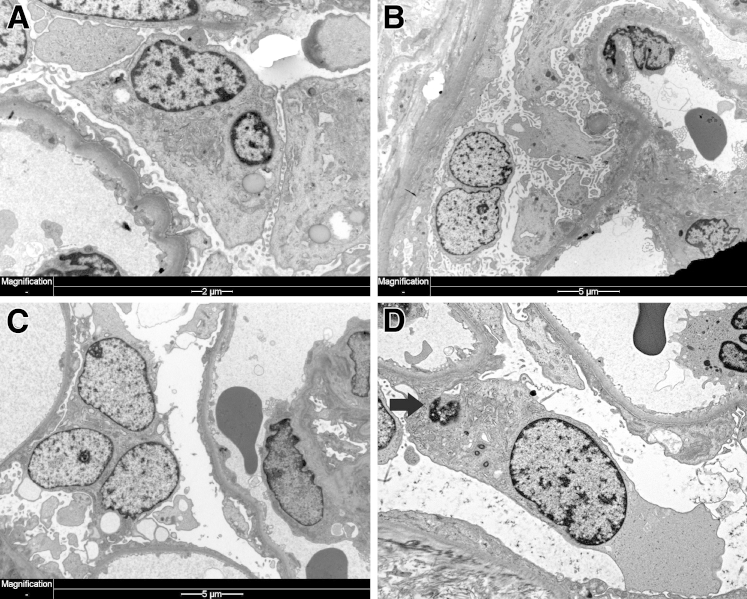

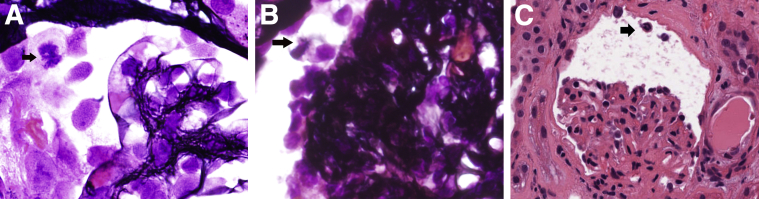

Figure 2.

Mitotic podocytes in human glomerular diseases. A: IgA nephropathy from 20-year-old woman with hematuria and necrotizing IgA. Mitotic podocyte (arrow) among numerous detached counterparts (silver stain). B: Collapsing FSGS from a 54-year-old man with a protein level of 8.5 g/dL. Half mitotic spindle in detached podocyte (arrow) in a glomerulus with implosion of the capillary loops (silver stain). C: Drug-induced MCD in an 84-year-old woman with a protein level of 6 g/dL. Mitotic podocyte traveling toward the proximal tubule pole of the glomerulus (arrow) (H&E). Original magnification, ×1000 (A and B); ×400 (C).

MC in Glomerular Diseases

MC as a form of cell death was first observed in the 1930s in irradiated cancer tissues that had abnormal nuclear configurations and spatial distribution of chromosomes. Therefore, this type of cell death was called mitotic- or cell division–associated death.46–48 MC is heterogeneous at least in carcinogenesis, characterized by molecular markers, including cyclin B1–dependent kinase Cdk1, pololike kinases and aurora kinases, cell-cycle checkpoint proteins, survivin, p53, caspases, and members of the Bcl-2 family.46 There are four different types: i) caspase independent; ii) caspase dependent, which is the intermediate step to apoptosis; iii) inducer of ploidy cycle, responsible for tumor cell survival mechanism; and iv) the standalone subtype of apoptosis.47,48 Podocytes in mitosis have not been assessed systematically in proliferative glomerulonephritides. However, most experienced renal pathologists have come across an occasional podocyte in mitosis usually free floating in the Bowman space (Figure 2). A single study by Nagata et al49 reported one mitotic figure in a single podocyte in a case of FSGS among 164 renal biopsy specimens with glomerular disease. The examples shown in Figure 2, A–C, are from patients with significant proteinuria (necrotizing IgA, collapsing glomerulopathy, and MCD, respectively). Mitotic podocytes associated with proteinuria may be a desperate but aborted attempt to regenerate epithelial injury. Podocyte multinucleation on the other hand is a recognized feature of aberrant mitosis.23,28 Nagata et al23 were intrigued by this phenomenon and reported it in 1998, but the literature remained remarkably poor on this subject. In lieu of the fact that aberrant mitosis and podocyte binucleation are synonymous to MC, we retrospectively reviewed consecutive renal biopsy specimens in an exact number (n = 164) as in the study by Nagata et al.23 We found twice as many (n = 12) multinucleated podocytes.3 All cases had significant proteinuria, and diagnoses included minimal change, FSGS, IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, collapsing glomerulopathy, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Foot process effacement was invariably present in association with binucleated podocytes.

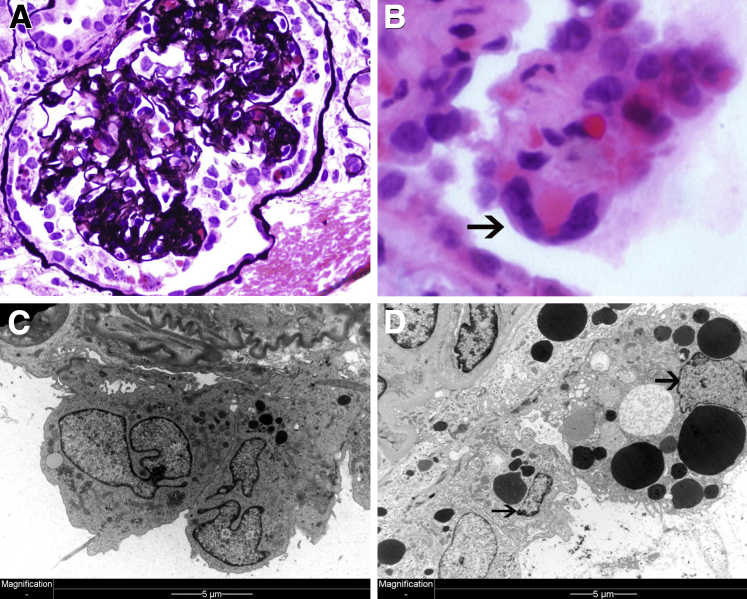

Binucleated podocytes are usually enlarged and reveal cytoplasmic and nuclear changes. For example, nuclei may appear edematous with one or more nucleoli (dotlike nuclear chromatin condensation) (Figure 3C). Unusual features include micronuclei, an indication of genomic instability and a feature of MC (Figure 3D). In fact, micronuclei are thought to derive from nuclear blebs.28 Cytoplasmic composition is also altered in MC with increased number of organelles, such as mitochondria and lipid droplets (Figure 3A) or cytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 3C). Sometimes, podocytes become trinucleated (Figure 3C). It appears that MC is frequent in injured podocytes that are forced to enter the cell cycle. The classic example of mature podocytes reentering the cell cycle is HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN), a type of collapsing glomerulopathy (FSGS).

Figure 3.

Mitotic podocytes in human glomerular diseases. A: IgA nephropathy. Hypertrophic, binucleated podocyte with an increased number of cytoplasmic organelles apparent on a renal biopsy specimen from a 58-year-old patient with a creatinine level of 2.2 mg/dL and a protein level of 1.1 g/dL. B: Lupus membranous. Binucleated detached podocyte apparent on a renal biopsy specimen from a 31-year-old woman with a urinary protein excretion of 4.2 g per 24 hours and a normal creatinine level. C: FSGS. Trinucleated podocyte apparent on a renal biopsy specimen from a 23-year-old man with a protein level of 12.5 g/dL. D: Recurrent FSGS. Micronucleolus next to podocyte nucleus (arrow) is apparent on a transplant renal biopsy specimen from a 23-year-old man with a protein level of 12.3 g/dL.

HIV-Associated Collapsing Glomerulopathy

Viral infection may trigger podocyte proliferation and cause implosion (collapse) of capillary loops (Figure 4A). HIV can infect podocytes (and parietal epithelial cells), leading to podocyte mitosis and HIV nephropathy.50,51 Switch to a proliferative podocyte phenotype is associated with loss of mature podocyte markers, such as WT1 and p27, p57, cyclin D1, cyclin A, and Ki-67 expression.22 Podocyte multinucleation is a predominant feature of HIVAN previously thought of as a compensatory mechanism of podocyte repair.51,52 However, on the basis of our current understanding, it appears that virus-induced podocyte mitosis is catastrophic, driving podocytes to cell death via MC. Notably, these tightly packed podocytes pile up on top of each other but to large extent remain attached to the GBM, and there is no evidence of overt foot process effacement. There is no evidence of apoptotic nuclear condensation. Instead, podocytes are multinucleated, and the cytoplasm appears fragile with cytoplasmic dense (osmiophilic) bodies (lysosomes) (Figure 4, C and D). Eventually, these multinucleated podocytes detach from the GBM, disrupt the cytoplasm, and release the nucleus and cytoplasmic contents into the Bowman space (Figure 4D). Multinucleated podocytes are frequent in HIVAN (Figure 4, B and C), and actual podocyte mitoses can be seen (Figure 2B). However, the connection with MC and aberrant cell death is still vague and little studied experimentally or clinically. For example, a recent study found that 53BP1 aggregates in the nuclei of HIV syncytia elicited by the HIV-1 envelope as a consequence of nuclear fusion. Knockdown of 53BP1 induces abnormal mitoses in HIV-1 envelope–induced syncytia, leading to selective destruction through mitochondria-dependent and caspase-dependent pathways. Thus, depletion of 53BP1 triggers the demise of HIV-1–elicited syncytia through MC.53 This suggests that new therapies that modify MC cell death may hold promise as new HIVAN therapies.

Figure 4.

Mitotic catastrophe in HIVAN. A: Collapsing glomerulopathy from a 34-year-old man who presented with acute renal failure; both visceral and parietal podocytes are numerous, proliferating over imploded capillary loops (silver stain). B: On high magnification, gigantic, multinucleated podocytes are apparent (arrow) (H&E). C: Electron microscopy highlights even more binucleated podocytes; podocytes also contain numerous cytoplasmic osmiophilic vacuoles characteristic of HIVAN. Podocytes are, however, still attached to foot processes, attempting to maintain functionality perhaps but apparently unable to divide. D: Podocyte death eventually ensues in binucleated (arrows) HIV-infected podocytes. Disintegrating cytoplasm and expulsion of cytoplasmic contents are shown. Original magnification, ×400 (A); ×1000 (B).

Diabetic Glomerulosclerosis, Podocyte Hypertrophy, and Progressive Glomerular Disease

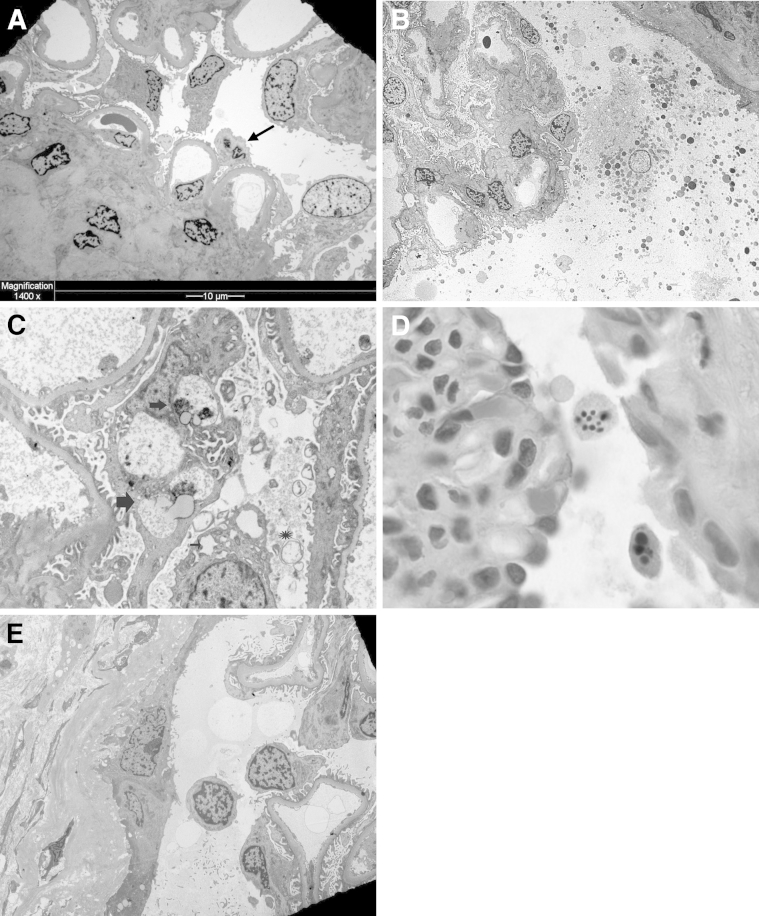

Apoptosis is thought to be a major mechanism by which podocytes die in diabetes and progressive glomerular disease.5–10,54 However, apoptotic cell death is rarely seen in diabetic glomeruli in situ, despite numerous experimental studies that provide biochemical evidence using transgenic podocyte cell lines. In our experience (H.L.) with thousands of renal biopsy specimens, we have not seen apoptotic podocytes in renal biopsy specimens with diabetes. The typical and diagnostic findings in advanced diabetes are mesangial glomerulosclerosis and GBM thickening. Podocytes invariably have foot process effacement and podocyte hypertrophy with frequent detachment but no condensed nuclei or nuclear fragmentation to suggest apoptosis; binucleated podocytes are rarely seen (Figure 5A). Hypertrophic podocytes in response to experimental mechanical injury are an attempt to recover denuded GBM stretches left behind from detached and lost podocytes.55 As previously described, hypertrophy represents cell cycle entry and arrest at the G2/M phase.20 Podocyte hypertrophy is not infrequent in diabetic injury in humans, but whether this is a compensatory mechanism that may trigger MC secondary to diabetes is unknown. Studies on the pathology of podocyte death may be an important parameter to evaluate in diabetes, particularly as new therapies that target interception of MC and cell death are advancing.3,45

Figure 5.

A: Podocyte hypertrophy in diabetes. Advanced diabetic glomerulosclerosis shows thick capillary loops and mesangial sclerosis. Most podocytes are hypertrophic and partially detached from the glomerular basement membrane (GBM); an occasional binucleated podocyte with decreased and condensed cytoplasm possibly due to podocyte death via MC is apparent. B: Podocyte necrosis. Exploded podocyte in the Bowman space shows ruptured plasma membrane, clear (edematous) nucleus, and dispersed cytoplasmic organelles apparent on a transplant renal biopsy specimen from a patient with severe acute renal failure secondary to antibody-mediated rejection (EM). C: Podocyte autophagy. There are variably shaped, membrane-bound organelles; some have double membrane (asterisk), and others have single membrane consistent with lysosomes or lysosomes in transition (autophagolysosomes) (thick arrows). Dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum (thin arrow), a feature of autophagy, is also present in this renal biopsy specimen from a 56-year-old man with a urinary protein excretion of 1 g per 24 hours (EM). D: Podocyte apoptosis. Detached podocytes have reduced volume and condensed and fragmented nuclei with apoptotic bodies apparent on a renal biopsy specimen from a child with congenital nephrotic syndrome (diffuse mesangial sclerosis) and a urinary protein excretion rate of 12 g per 24 hours (H&E). E: Detached viable podocyte. Detached podocyte with viable-appearing nucleus floats in the Bowman space adjacent to parietal epithelial cells apparent on a renal biopsy specimen from a 7-year-old girl after bone marrow transplantation who presented with acute renal failure (EM). Original magnification, ×1500 (B and E); ×5000 (C); ×1000 (D).

MC Versus Other Forms of Podocyte Death

Necrotic Cell Death

This type of cell death is due to irreversible pathologic extrinsic injury and is characterized by an increase in cell volume due to edema (oncosis), cytoplasmic membrane disruption, and loss of electron density in the cytoplasm. In early stages, cytoplasmic organelles swell, and in late stages the cell becomes leaky with plasma membrane blebs; the nucleus also undergoes lysis. Because of plasma membrane disintegration and organelle and nuclear dispersion, inflammation ensues in the adjacent tissues. Necrosis is a manifestation of severe acute injury, the result of direct or indirect insults.56,57 Necrotic cell death was thought to be a passive phenomenon, but meanwhile several inflammation-related programmed forms of necrosis were described (caspase 1–mediated proptosis and RIP-1 kinase–mediated necroptosis). However, their role in podocyte loss is not defined yet.58 The example shown in Figure 5B is from a kidney transplant patient with severe acute renal failure secondary to antibody (C4d)–mediated rejection, a type of endothelial injury that may lead to hemorrhagic necrosis and glomerular thrombosis. Necrotizing glomerulonephritides may have similar effects on podocytes.

Autophagic Podocyte Death

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved housekeeping process in which cells acting in self-defense degrade their cytoplasmic contents and eliminate protein aggregates and damaged organelles.57,59 Three forms of autophagy are recognized to date: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy.59,60 The first is the most important and is characterized by sequestration of large organelles, such as mitochondria and ribosomes within a double membrane bound vacuole called the autophagosome. The hallmark of autophagosomes is the presence of the double-limiting membrane.60,61 The second form, microautophagy, is characterized by entry of cytoplasmic molecules and small organelles into lysosomes through membrane invagination (Figure 5C). However, the different types of autophagy do not operate in isolation but interact with each other.59 Lysosomes are the final destination of degraded cytoplasmic waste in autophagosomes, and it is in this capacity that lysosomes regulate organelle turnover by autophagy.58–61 In postmitotic cells cytoplasmic waste includes lipids and remnants of digested membranes that are evident as loose threads inside lysosomes. Lipids can be osmiophilic and stain dark on EM. Lipofuscin in aging cells is one such dark staining lysosomal lipid. Lysosomes in contrast to autophagosomes are bound by a single membrane. However, at any given time, physiologically recycled cytoplasmic organelles may be found in transition from one state to another, and their morphologic features can vary from autophagosomes, transient vesicles, partially degraded lysosomes, to autophagic vacuoles. Precise definitions of the various cytoplasmic vacuoles are beyond the scope of this review and can be found in excellent authoritative literature.16,62 However, it should be mentioned that rough endoplasmic reticulum stress (Figure 5) is also present in autophagic cell death after ischemic, toxic, immunologic, and oxidative injuries and may trigger autophagy in renal epithelial cells. The potential of modifying the course of glomerular disease by understanding podocyte autophagy is currently proposed. An obvious possibility is lysosomal storage diseases, but little work has been performed in this area.63,64 In random renal biopsy specimens, podocyte cytoplasmic vacuoles and lysosomes may represent routine cytoplasmic debris removal and homeostatic maintenance. Podocytes are indeed prone to constitutive autophagy as a maintenance mechanism.65,66 Few studies on autophagy in human renal disease are reported. For example, Sato et al67 examined renal biopsy specimens of 16 children with progressing IgA nephropathy; autophagy correlated with glomerulosclerosis, prompting the authors to suggest that lack of complete cytoplasmic waste digestion infers podocyte cell death and glomerulosclerosis. In animal models, the puromycin aminonucleoside–induced nephrosis demonstrates that autophagy may affect podocytes in 2 ways: helping to restore cytoplasmic podocyte integrity or, if excessive, leading to direct podocyte cell death.13 How autophagy proceeds to involve cytoplasmic organelles, including mitochondria, respiratory exchange ratio, the proteosome, and lysosomes, remains to be resolved, but it seems that science is fast evolving to link the various responses during autophagic cell death by integrating molecular and structural podocyte cell changes.68 Although autophagy is primarily a cytoplasm-focused enterprise, recent studies suggest that nuclei may be targeted as well. For example, micronuclei, a feature of MC, can be subjected to autophagic removal, suggesting that autophagy may have genome-stabilizing effects and thus may also affect MC.69

Apoptotic Podocyte Death

Apoptosis is studied in various experimental glomerular injuries. Most podocyte apoptosis data are derived from in vitro experiments using transgenic cell lines. Morphologic data of apoptotic podocytes are rarely presented.1 Instead, biochemical assays of DNA fragmentation (TUNEL assay) and enzymatic (caspase) assays are consistently used and interpreted as evidence of apoptosis. However, none of these assays definitively distinguishes apoptosis from other types of cell death. For example, in renal biopsy specimens with FSGS, diabetes, or other glomerular diseases, apoptosis has not been reported,1 but dozens of publications consider it a given. It is possible that fragmented podocyte nuclei disappear fast, but if apoptosis is a major mechanism of podocyte cell death in situ, given the thousands of renal biopsies performed, renal pathologists would have frequently witnessed the phenomenon and reported it in the literature. An exceptional example of an apoptotic podocyte in a renal biopsy specimen is shown in Figure 5D. Apoptotic podocytes have a densely stained nucleus and condensed eosinophilic cytoplasm with characteristically shrunken cytoplasm and nuclear fragmentation (apoptotic bodies). Lack of morphologic evidence of apoptosis in experimental or human studies has cast serious doubts on whether apoptosis is in fact a common mechanism of podocyte loss in situ. Viable podocytes with no signs of nuclear condensation are recovered from urine and grown in culture, suggesting that detached podocytes from the GBM are not equivalent to dead podocytes by apoptosis.70 In human renal biopsy specimens, detached, viable-appearing podocytes floating free in the Bowman space are occasionally seen (Figure 5E).

Is Foot Process Effacement in Minimal Change and FSGS All We Should Be Looking For?

Both MCD and FSGS are common podocyte diseases diagnosed on EM by diffuse or focal foot process effacement, respectively. Some authors consider them one disease in a spectrum.1,18 Both can be diagnostically problematic on renal biopsy specimens when foot process effacement is minor in MCD or FSGS is absent on H&E because of sampling error. Both may respond to steroids and, if resistant, progress to glomerulosclerosis attributed to podocyte loss, particularly in aggressive FSGS. The mechanism of podocyte loss in FSGS is still debated. In situ podocytes loss in human FSGS is thought to involve apoptosis but is not demonstrated. If apoptosis were the pathway, then podocytes must die before detachment. Animal models, for example, the diphtheria toxin–induced FSGS, anti–Thy-1.1 nephritis, or transforming growth factor β overexpression, suggest an apoptotic cell death.5,11,12 Genetically engineered animals also have coordinated signaling between slit diaphragm proteins, such as nephrin (a cause of MCD and FSGS when mutated), and structural cytoplasmic proteins synergistically act to maintain nuclear and cytoplasmic integrity in podocytes. Surprisingly, nephrin loss does not cause apoptosis, implying that other molecules may compensate for nephrin signaling.71 These and other studies have raised doubts about podocyte apoptosis playing a role in hereditary and/or other types of FSGS. Our recent work with Adriamycin-induced FSGS documents that podocyte loss is driven by MDM2-dependent MC because MDM2 degrades p53, which ensures cell cycle arrest via induction of p21 and other cell cycle regulators.3 Therefore, pharmacologic MDM2 inhibition prevented MC of podocytes, which suppressed proteinuria and prevented progressive glomerulosclerosis and subsequent tubulointerstitial disease. Taken together nuclear abnormalities point to podocyte disease beyond foot process effacement. Binucleated cells or podocytes with micronuclei or otherwise asymmetric nuclear divisions indicate aneuploidy, implying MC as a cause for podocyte loss, which may not necessarily be targeted by steroids and requires alternative treatments to reinstate cell cycle arrest in podocytes.

Summary and Perspectives

Apoptosis and necrosis as forms of podocyte loss were extensively discussed previously, but numerous other forms of cell death exist. In view of the fact that apoptotic podocytes are rarely spotted in human renal biopsy specimens and podocyte necrosis may be limited to rare cases, it seems likely that in most glomerular disorders podocyte loss involves yet unknown or poorly characterized mechanisms. MC is one of those poorly recognized forms of podocyte loss. Although few studies have addressed MC in glomerular disease so far, it appears that the best example of podocyte MC may yet be HIVAN, where the promitotic effects of HIV DNA and HIV proteins trigger podocyte loss and collapsing glomerulopathy. MC was also found to drive podocyte loss in experimental Adriamycin nephropathy, which suggests that this mechanism may also contribute to drug-induced FSGS in humans. Currently, the relative contribution of MC to podocyte loss in other forms of FSGS, in MCD, immune complex glomerulonephritis, or other podocytopathies, remains to be determined. MDM2 blockade is currently the only therapeutic intervention reported to suppress podocyte MC, but other cell cycle–modifying drugs are likely to have similar effects. Given our limited knowledge about this evolving topic, therapeutic targeting of MC in human proteinuric glomerular disease remains speculative. Currently, it becomes necessary that we examine which of the many forms of cell death contribute to podocyte loss in vivo. This requires a careful assessment of podocyte disease beyond foot process effacement in the first place.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dana Thomasova for preparing Figure 1.

Footnotes

Supported by grant AN372/12-2 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (H.J.A.) and by grant NIDDK079333 the from the O’Brien Kidney Center at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (H.L.).

References

- 1.Kriz W., Shirato I., Nagata M., Lehir M., Lemley K.V. The podocyte’s response to stress: the enigma of foot process effacement. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304:F333–F347. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00478.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wharram B.L., Goyal M., Wiggins J.E., Sanden S.K., Hussain S., Filipiak W.E., Saunders T.L., Dysko R.C., Kohno K., Holzman L.B., Wiggins R.C. Podocyte depletion causes glomerulosclerosis: diphtheria toxin-induced podocyte depletion in rats expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor transgene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2941–2952. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulay S.R., Thomasova D., Ryu M., Kulkarni O.P., Migliorini A., Bruns H., Gröbmayr R., Lazzeri E., Lasagni L., Liapis H., Romagnani P., Anders A.J. Podocyte loss involves MDM2-driven mitotic catastrophe. J Pathol. 2013;230:322–335. doi: 10.1002/path.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Migliorini A., Angelotti M.L., Mulay S.R., Kulkarni O.O., Demleitner J., Dietrich A., Shankland S., Sagrinati C., Ballerini L., Peired A., Liapis H., Romagnani P., Anders H.J. The antiviral cytokines IFN-α and IFN-β modulate podocytes and parietal epithelial cells: implications for IFN toxicity, viral glomerulonephritis and glomerular regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H.S. Mechanisms and consequences of TGF-ss overexpression by podocytes in progressive podocyte disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1169-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stieger N., Worthmann K., Schiffer M. The role of metabolic and haemodynamic factors in podocyte injury in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:207–215. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bottinger E.P. TGF-beta in renal injury and disease. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim S.K., Park S.H. The high glucose-induced stimulation of B1R and B2R expression via CB(1)R activation is involved in rat podocyte apoptosis. Life Sci. 2012;91:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y.Q., Wang X.X., Yao X.M., Zhang D.L., Yang X.F., Tian S.F., Wang N.S. MicroRNA-195 promotes apoptosis in mouse podocytes via enhanced caspase activity driven by BCL2 insufficiency. Am J Nephrol. 2011;34:549–559. doi: 10.1159/000333809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziyadeh F.N., Wolf G. Pathogenesis of the podocytopathy and proteinuria in diabetic glomerulopathy. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2008;4:39–45. doi: 10.2174/157339908783502370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou M.S., Yu J., Nie G.M., He W.S., Luo L.M., Xu H.T. 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 decreases Adriamycin-induced podocyte apoptosis and loss. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:290–299. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiffer M., Bitzer M., Roberts I.S., Kopp J.B., ten Dijke P., Mundel P., Böttinger E.P. Apoptosis in podocytes induced by TGF-beta and Smad7. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:807–816. doi: 10.1172/JCI12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartleben B., Gödel M., Meyer-Schwesinger C., Liu S., Ulrich T., Köbler S., Wiech T., Grahammer F., Arnold S.J., Lindenmeyer M.T., Cohen C.D., Pavenstädt H., Kerjaschki D., Mizushima N., Shaw A.S., Walz G., Huber T.B. Autophagy influences glomerular disease susceptibility and maintains podocyte homeostasis in aging mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1084–1096. doi: 10.1172/JCI39492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galluzzi L., Vitale I., Abrams J.M., Alnemri E.S., Baehrecke E.H., Blagosklonny M.V., Dawson T.M., Dawson V.L., El-Deiry W.S., Fulda S., Gottlieb E., Green D.R., Hengartner M.O., Kepp O., Knight R.A., Kumar S., Lipton S.A., Lu X., Madeo F., Malorni W., Mehlen P., Nuñez G., Peter M.E., Piacentini M., Rubinsztein D.C., Shi Y., Simon H.U., Vandenabeele P., White E., Yuan J., Zhivotovsky B., Melino G., Kroemer G. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tharaux P.L., Huber T.B. How many ways can a podocyte die? Semin Nephrol. 2012;32:394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehrpour M., Esclatine A., Beau I., Codogno P. Autophagy in health and disease, 1: regulation and significance of autophagy: an overview. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C776–C785. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00507.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavenstadt H., Kriz W., Kretzler M. Cell biology of the glomerular podocyte. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:253–307. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liapis H. Molecular pathology of nephrotic syndrome in childhood: a contemporary approach to diagnosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2008;11:154–163. doi: 10.2350/07-11-0375.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasagni L., Ballerini L., Angelotti M.L., Parente E., Sagrinati C., Mazzinghi B., Peired A., Ronconi E., Becherucci F., Bani D., Gacci M., Carini M., Lazzeri E., Romagnani P. Notch activation differentially regulates renal progenitors proliferation and differentiation toward the podocyte lineage in glomerular disorders. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1674–1685. doi: 10.1002/stem.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall C.B., Shankland S.J. Cell cycle and glomerular disease: a minireview. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2006;102:e39–e48. doi: 10.1159/000088400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okada H., Mak T.W. Pathways of apoptotic and non-apoptotic death in tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barisoni L., Bruggeman L.A., Mundel P., D’Agati V.D., Klotman P.E. Podocyte cell cycle regulation and proliferation in collapsing glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 2000;58:137–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagata M., Nakayama K., Terada Y., Hoshi S., Watanabe T. Cell cycle regulation and differentiation in the human podocyte lineage. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1511–1520. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65739-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S., Kim J.H., Moon K.C., Hong H.K., Lee H.S. Cell-cycle mechanisms involved in podocyte proliferation in cellular lesion of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:19–27. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall C.B., Krofft R.D., Pippin J.W., Shankland S.J. CDK inhibitor p21 is prosurvival in Adriamycin-induced podocyte injury, in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1140–F1151. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00216.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petermann A.T., Pippin J., Hiromura K., Monkawa T., Durvasula R., Couser W.G., Kopp J., Shankland S.J. Mitotic cell cycle proteins increase in podocytes despite lack of proliferation. Kidney Int. 2003;63:113–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin S.V., Pichler R., Wada T., Vaughan M., Durvasula R., Shankland S.J. The role of cell cycle proteins in glomerular disease. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23:569–582. doi: 10.1053/s0270-9295(03)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanson P.E., Carroll S.B., Zhang X.F., Mackey M.A. Spontaneous premature chromosome condensation, micronucleus formation, and non-apoptotic cell death in heated HeLa S3 cells: ultrastructural observations. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:963–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sagrinati C., Netti G.S., Mazzinghi B., Lazzeri E., Liotta F., Frosali F., Ronconi E., Meini C., Gacci M., Squecco R., Carini M., Gesualdo L., Francini F., Maggi E., Annunziato F., Lasagni L., Serio M., Romagnani S., Romagnani P. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman’s capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lasagni L., Romagnani P. Glomerular epithelial stem cells: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1612–1619. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romagnani P. Toward the identification of a “renopoietic system”? Stem Cells. 2009;27:2247–2253. doi: 10.1002/stem.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ronconi E., Sagrinati C., Angelotti M.L., Lazzeri E., Mazzinghi B., Ballerini L., Parente E., Becherucci F., Gacci M., Carini M., Maggi E., Serio M., Vannelli G.B., Lasagni L., Romagnani S., Romagnani P. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Appel D., Kershaw D.B., Smeets B., Yuan G., Fuss A., Frye B., Elger M., Kriz W., Floege J., Moeller M.J. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lazzeri E., Crescioli C., Ronconi E., Mazzinghi B., Sagrinati C., Netti G.S., Angelotti M.L., Parente E., Ballerini L., Cosmi L., Maggi L., Gesualdo L., Rotondi M., Annunziato F., Maggi E., Lasagni L., Serio M., Romagnani S., Vannelli G.B., Romagnani P. Regenerative potential of embryonic renal multipotent progenitors in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:3128–3138. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura T., Tsuchiya K., Watanabe M. Crosstalk between Wnt and Notch signaling in intestinal epithelial cell fate decision. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:705–710. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2087-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grouls S., Iglesias D.M., Wentzensen N., Moeller M.J., Bouchard M., Kemler R., Goodyer P., Niggli F., Gröne H.-J., Kriz W., Koesters R. Lineage specification of parietal epithelial cells requires {beta}-catenin/Wnt signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:63–72. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burnworth B., Pippin J., Karna P., Akakura S., Krofft R., Zhang G., Hudkins K., Alpers C.E., Smith K., Shankland S.J., Gelman I.H., Nelson P.J. SSeCKS sequesters cyclin D1 in glomerular parietal epithelial cells and influences proliferative injury in the glomerulus. Lab Invest. 2012;92:499–510. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benigni A., Morigi M., Rizzo P., Gagliardini E., Rota C., Abbate M., Ghezzi S., Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. Inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme promotes renal repair by limiting progenitor cell proliferation and restoring the glomerular architecture. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peired A., Angelotti M.L., Ronconi E., la Marca G., Mazzinghi B., Sisti A., Lombardi D., Giocaliere E., Della Bona M., Villanelli F., Parente E., Ballerini L., Sagrinati C., Wanner N., Huber T.B., Liapis H., Lazzeri E., Lasagni L., Romagnani P. Proteinuria impairs glomerular regeneration by sequestering retinoic acid. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012090950. [Epub ahead of press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J., Pippin J.W., Vaughan M.R., Krofft R.D., Taniguchi Y., Romagnani P., Nelson P.J., Liu Z.H., Shankland S.J. Retinoids augment the expression of podocyte proteins by glomerular parietal epithelial cells in experimental glomerular disease. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2012;121:e23–e37. doi: 10.1159/000342808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J., Pippin J.W., Krofft R.D., Naito S., Liu Z., Shankland S.J. Podocyte Repopulation by Renal Progenitor Cells Following Glucocorticoids Treatment in Experimental FSGS. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00020.2013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darisipudi M.N., Kulkarni O.P., Sayyed S.G., Ryu M., Migliorini A., Sagrinati C., Parente E., Vater A., Eulberg D., Klussmann S., Romagnani P., Anders H.J. Dual blockade of the homeostatic chemokine CXCL12 and the proinflammatory chemokine CCL2 has additive protective effects on diabetic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sayyed S.G., Hägele H., Kulkarni O.P., Endlich K., Segerer S., Eulberg D., Klussmann S., Anders H.J. Podocytes produce homeostatic chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCL12, which contributes to glomerulosclerosis, podocyte loss and albuminuria in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2445–2454. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olivetti G., Anversa P., Melissari M., Loud A.V. Morphometry of the renal corpuscle during postnatal growth and compensatory hypertrophy. Kidney Int. 1980;17:438–454. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lasagni L., Lazzeri E., Shankland S.J., Anders H.J., Romagnani P. Podocyte mitosis - a catastrophe. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:13–23. doi: 10.2174/1566524011307010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castedo M., Perfettini J.L., Roumier T., Valent A., Raslova H., Yakushijin K., Horne D., Feunteun J., Lenoir G., Medema R., Vainchenker W., Kroemer G. Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition. Oncogene. 2004;23:2825–2837. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vakifahmetoglu H., Olsson M., Zhivotovsky B. Death through a tragedy: mitotic catastrophe. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1153–1162. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vitale I., Galluzzi L., Castedo M., Kroemer G. Mitotic catastrophe: a mechanism for avoiding genomic instability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;13:385–392. doi: 10.1038/nrm3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagata M., Yamaguchi Y., Komatsu Y., Ito K. Mitosis and the presence of binucleate cells among glomerular podocytes in diseased human kidneys. Nephron. 1995;70:68–71. doi: 10.1159/000188546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilen C.B., Tilton J.C., Doms R.W. HIV: cell binding and entry. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006866. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a006866 pii: a006866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyatt C.M., Meliambro K., Klotman P.E. Recent progress in HIV-associated nephropathy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:147–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041610-134224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Craigie R. The molecular biology of HIV integrase. Future Virol. 2012;7:679–686. doi: 10.2217/FVL.12.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perfettini J.L., Nardacci R., Séror C., Raza S.Q., Sepe S., Saïdi H., Brottes F., Amendola A., Subra F., Del Nonno F., Chessa L., D’Incecco A., Gougeon M.L., Piacentini M., Kroemer G. 53BP1 represses mitotic catastrophe in syncytia elicited by the HIV-1 envelope. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:811–820. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jain S., De Petris L., Hoshi M., Akilesh S., Chatterjee R., Liapis H. Expression profiles of podocytes exposed to high glucose reveal new insights into early diabetic glomerulopathy. Lab Invest. 2011;91:488–498. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petermann A.T., Hiromura K., Blonski M., Pippin J., Monkawa T., Durvasula R., Couser W.G., Shankland S.J. Mechanical stress reduces podocyte proliferation in vitro. Kidney Int. 2002;61:40–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ueda H., Fujita R., Yoshida A., Matsunaga H., Ueda M. Identification of prothymosin-alpha1, the necrosis-apoptosis switch molecule in cortical neuronal cultures. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:853–862. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kroemer G., Galluzzi L., Vandenabeele P., Abrams J., Alnemri E.S., Baehrecke E.H., Blagosklonny M.V., El-Deiry W.S., Golstein P., Green D.R., Hengartner M., Knight R.A., Kumar S., Lipton S.A., Malorni W., Nuñez G., Peter M.E., Tschopp J., Yuan J., Piacentini M., Zhivotovsky B., Melino G. Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:3–11. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Linkermann A., Bräsen J.H., Himmerkus N., Liu S., Huber T.B., Kunzendorf U., Krautwald S. Rip1 (receptor-interacting protein kinase 1) mediates necroptosis and contributes to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2012;81:751–761. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Terman A., Gustafsson B., Brunk U.T. Autophagy, organelles and ageing. J Pathol. 2007;211:134–143. doi: 10.1002/path.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurz T., Terman A., Brunk U.T. Autophagy, ageing and apoptosis: the role of oxidative stress and lysosomal iron. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;462:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klionsky D.J. Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science. 2000;290:1717–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y., Martinez-Vicente M., Krüger U., Kaushik S., Wong E., Mandelkow E.M., Cuervo A.M., Mandelkow E. Synergy and antagonism of macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy in a cell model of pathological tau aggregation. Autophagy. 2010;6:182–183. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.1.10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang Z., Klionsky D.J. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:814–822. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ylä-Anttila P., Vihinen H., Jokitalo E., Eskelinen E.L. Monitoring autophagy by electron microscopy in mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:143–164. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shimada Y., Klionsky D.J. Autophagy contributes to lysosomal storage disorders. Autophagy. 2012;8:715–716. doi: 10.4161/auto.19920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huber T.B., Edelstein C.L., Hartleben B., Inoki K., Jiang M., Koya D., Kume S., Lieberthal W., Pallet N., Quiroga A., Ravichandran K., Susztak K., Yoshida S., Dong Z. Emerging role of autophagy in kidney function, diseases and aging. Autophagy. 2012;8:1009–1031. doi: 10.4161/auto.19821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sato S., Yanagihara T., Ghazizadeh M., Ishizaki M., Adachi A., Sasaki Y., Igarashi T., Fukunaga Y. Correlation of autophagy type in podocytes with histopathological diagnosis of IgA nephropathy. Pathobiology. 2009;76:221–226. doi: 10.1159/000228897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deffieu M., Bhatia-Kissová I., Salin B., Klionsky D.J., Pinson B., Manon S., Camougrand N. Increased cytochrome b reduction and mitophagy components are required to trigger nonspecific autophagy following induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:415–426. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rello-Varona S., Lissa D., Shen S., Niso-Santano M., Senovilla L., Mariño G., Vitale I., Jemaá M., Harper F., Pierron G., Castedo M., Kroemer G. Autophagic removal of micronuclei. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:170–176. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.1.18564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vogelmann S.U., Nelson W.J., Myers B.D., Lemley K.V. Urinary excretion of viable podocytes in health and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F40–F48. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00404.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Doné S.C., Takemoto M., He L., Sun Y., Hultenby K., Betsholtz C., Tryggvason K. Nephrin is involved in podocyte maturation but not survival during glomerular development. Kidney Int. 2008;73:697–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]