Key Points

CD123 CAR T cells specifically target CD123+ AML cells.

AML patient-derived T cells can be genetically modified to lyse autologous tumor cells.

Abstract

Induction treatments for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have remained largely unchanged for nearly 50 years, and AML remains a disease of poor prognosis. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation can achieve cures in select patients and highlights the susceptibility of AML to donor-derived immunotherapy. The interleukin-3 receptor α chain (CD123) has been identified as a potential immunotherapeutic target because it is overexpressed in AML compared with normal hematopoietic stem cells. Therefore, we developed 2 chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) containing a CD123-specific single-chain variable fragment, in combination with a CD28 costimulatory domain and CD3-ζ signaling domain, targeting different epitopes on CD123. CD123-CAR–redirected T cells mediated potent effector activity against CD123+ cell lines as well as primary AML patient samples. CD123 CAR T cells did not eliminate granulocyte/macrophage and erythroid colony formation in vitro. Additionally, T cells obtained from patients with active AML can be modified to express CD123 CARs and are able to lyse autologous AML blasts in vitro. Finally, CD123 CAR T cells exhibited antileukemic activity in vivo against a xenogeneic model of disseminated AML. These results suggest that CD123 CAR T cells are a promising immunotherapy for the treatment of high-risk AML.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a disease characterized by the rapid proliferation of immature myeloid cells in the bone marrow resulting in dysfunctional hematopoiesis.1 Although standard induction chemotherapy can induce complete remissions, many patients eventually relapse and succumb to the disease.2 Therefore, the development of novel therapeutics for AML is crucial. Recent advances in the immunophenotyping of AML cells have revealed several AML-associated cell surface antigens that may act as targets for future therapies.3 Indeed, preclinical investigations using antibodies targeting CD44, CD47, T-cell immunoglobulin mucin-3 (TIM-3), and the interleukin 3 receptor α chain (CD123) for the treatment of AML have been described and have demonstrated promising antileukemic activity in murine models.3,4 Additionally, 2 phase 1 trials for CD123-specific therapeutics have been completed, with both drugs displaying good safety profiles (ClinicalTrials.gov ID #NCT00401739 and #NCT00397579). Unfortunately, these CD123-targeting drugs had limited efficacy, suggesting that alternative and more potent therapies targeting CD123 may be required to observe antileukemic activity.

A possibly more potent alternative therapy for the treatment of AML is the use of T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) that redirect T-cell specificity toward cell surface tumor-associated antigens in a major histocompatibility complex–independent manner.5 In most cases, CARs consist of a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) from a monoclonal antibody fused to the signaling domain of CD3ζ and may contain a costimulatory endodomain.5 Several groups have developed CARs targeting various antigens for the treatment of B-cell malignancies,6-10 and many have gone on to evaluate CAR-expressing T cells in phase 1 clinical trials.11-15 In contrast, CAR-engineered T cells for the treatment of AML remain scarce.16-18

Here, we describe the generation of 2 novel CD123-targeting CARs using scFvs from previously described recombinant immunotoxins, 26292 and 32716, which bind distinct epitopes and have similar binding affinities for CD123.19 We hypothesized that T cells expressing CARs derived from either 26292 or 32716 would effectively redirect T-cell specificity against CD123-expressing cells. Using a standard 4-hour chromium-51 (51Cr) release assay, healthy donor T cells engineered to express the CD123 CARs efficiently lysed CD123+ cell lines and primary AML patient samples. Additionally, both of the CD123 CAR T cells activated multiple effector functions following coculture with CD123+ cell lines and primary AML patient samples. Further, CD123-targeting T cells did not ablate colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) or burst-forming unit erythroid (BFU-E) colonies from cord blood (CB). Importantly, while CD19-specific T cells had little impact on leukemic colony formation of primary AML samples, CD123-targeting T cells significantly reduced leukemic colony formation in vitro. Further, we show that AML-patient–derived T cells can express CD123 CARs and lyse autologous blasts in vitro. Finally, we demonstrate that CD123 CAR T cells displayed antileukemic effects in vivo in a xenogeneic model of AML.

Materials and methods

Colony-Forming Cell Assay

CD34+ cells from CB mononuclear cells or primary AML samples were selected using immunomagnetic column separation (Miltenyi Biotech). A total of 1 × 103 CD34+ CB cells or 5 × 103 CD34+ primary AML patient cells were cocultured for 4 hours with 2.5 × 104 or 1.25 × 105 CAR+ T cells, respectively. At the end of the 4-hour coculture, the entire cell mixture was transferred to a methylcellulose-based growth medium and plated in duplicate.20 Then 14 to 18 days later, CFU-GM and BFU-E colonies were enumerated. To normalize, the average colony number from CD19R-treated samples (n = 3) was set at 100% and the values from the other groups were adjusted using the following calculation:

|

.

Xenograft model of AML and bioluminescent imaging

Animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the City of Hope Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. NOD/Scid IL-2RγCnull mice were irradiated with 300 cGy 24 hours prior to intravenous injection of 0.5 × 106 KG1a-eGFP-ffluc cells. Five days later, mice were intravenously injected with 5 × 106 CAR+ cells. Leukemic progression was monitored by Xenogen imaging.21 Survival curves were constructed using Kaplan-Meier method and statistical analyses of survival were performed using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests with P < .05 considered significant.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v5.04. Unpaired Student t tests were used to identify significant differences between treatment groups. For further details please see the supplemental Methods on the Blood Web site.

Results

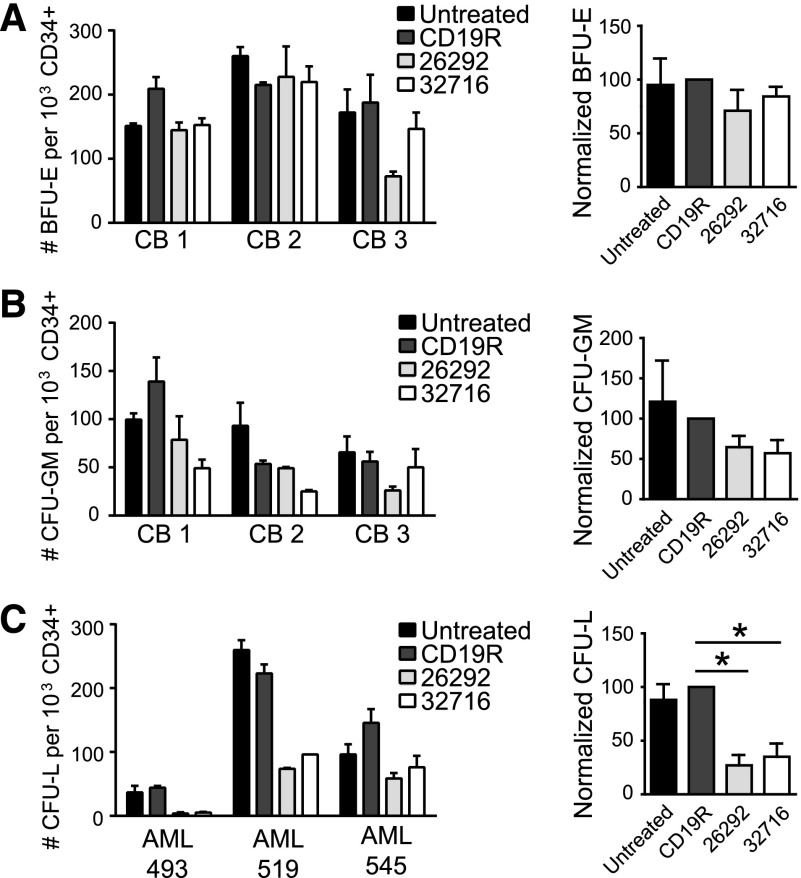

Generation of CD123 CAR-expressing T cells

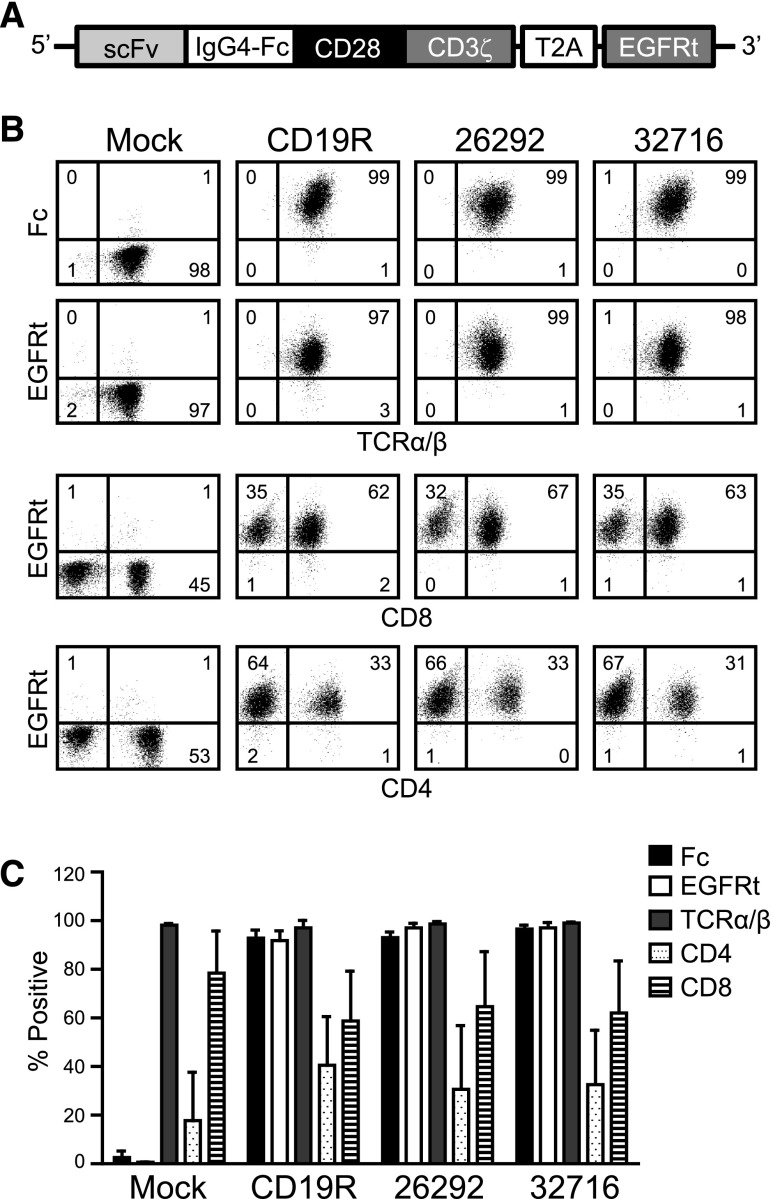

To redirect T-cell specificity, we developed lentiviral vectors encoding CD123 CARs. Each of the CARs consists of codon-optimized sequences encoding 1 of 2 CD123-specific scFvs, 26292, or 32716, which bind distinct epitopes and have similar binding affinities for CD123 (3.5 and 1.4 nM apparent affinities on CD123+ TF-1 cells, respectively19). The scFvs are fused in-frame to the human immunoglobulin G4 Fc region, a CD28 costimulatory domain, and the CD3ζ signaling domain. Just downstream of the CAR sequence is a T2A ribosome skip sequence and a truncated human EGFR (EGFRt) transduction marker (Figure 1A). OKT3-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were lenti-transduced, and CAR-expressing T cells were isolated by immunomagnetic selection using a biotinylated-cetuximab antibody followed by a secondary stain with antibiotin magnetic beads. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the PBMCs were obtained under protocols approved by the institutional review board. Following 1 rapid expansion cycle, the isolated cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for CAR surface expression and T-cell phenotype. Both Fc and EGFRt expression was >90% in the generated T-cell lines from 3 healthy donors, and final T-cell products consisted of a mixture of CD4- and CD8-positive T cells (Figure 1B-C).

Figure 1.

CD123-specific CARs can be expressed in healthy donor human T cells. (A) Schematic diagram of the CAR containing a modified immunoglobulin G4 hinge, a modified transmembrane and intracellular signaling domain of CD28, and the CD3ζ signaling domain. The T2A ribosomal skip sequence and the EGFRt transduction marker are also indicated. (B) Representative phenotype of mock- and lenti-transduced T cells derived from a single healthy donor. After immunomagnetic selection and 1 cycle of expansion, CAR-modified T cells were stained with biotinylated anti-Fc or biotinylated anti-cetuximab followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin and anti-TCRα/β, anti-CD4, or anti-CD8 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Quadrant placement is based on staining with isotype controls, and the percentage of cells falling in each quadrant is indicated. (C) Expression of indicated cell surface markers from 3 different healthy donor T-cell lines following immunomagnetic selection and 1 cycle of expansion. Data represent mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

CD123 CAR T cells specifically target CD123-expressing tumor cell lines

To confirm the specificity of our CD123 CAR T cells, we examined the ability of the genetically modified T cells to lyse 293T cells transiently transfected to express CD123 (293T-CD123; Figure 2A). Both CD123 CAR T cells efficiently lysed 293T-CD123 but not 293T cells transiently transfected to express CD19, demonstrating the specific recognition of CD123 (Figure 2B). We next investigated the in vitro cytolytic capacity of CD123-specific T cells against tumor cell lines endogenously expressing CD123. Expression of CD123 on the cell lines LCL and KG1a were confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure 2C). Both CD123-specific T-cell lines efficiently lysed LCL and KG1a target lines but not the CD123− K562 cell line (Figure 2D). CD19-specific T cells derived from the same donor (ie, pair-matched) effectively lysed CD19+ LCL targets but not CD19- KG1a or K562 targets (Figure 2D). Mock-transduced parental cells lysed only the positive control LCL-OKT3 cell line (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

CD123-specific CAR-expressing T cells lyse CD123-expressing tumor cell lines. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of 293T cells transiently transfected to express CD123 (top, black line) or CD19 (bottom, black line). Parental mock-transduced 293T cells were stained with either anti-CD123 or anti-CD19 antibodies (gray filled, top and bottom) to determine background expression levels. (B) Specific cytotoxicity of CD123-CAR–expressing T cells (26292 and 32716) against 293T cells expressing either CD123 (293T-CD123) or CD19 (293T-CD19) by chromium release assay. Data represent mean values of triplicate wells ± standard deviation (SD). (C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD123 on the AML cell line KG1a, the Epstein-Barr virus–transformed LCL cell line, and the CML cell line K562. Percentage of cells positive for CD123 staining (black line) over isotype controls (gray filled) are indicated in each histogram. (D) Specific cytotoxicity of CD123-CAR T cells (26292 and 32716) against the CD19+CD123+ LCL cell line and the CD19−CD123+ cell line KG1a by chromium release assay. OKT3-expressing LCL (LCL-OKT3) and the CD19− CD123− K562 cell lines were used as positive and negative control cell lines, respectively. Data represent mean values of triplicate wells ± SD. (E) CD123 CAR T cells, or control pair-matched T cells, from 3 healthy donors were cocultured with the indicated cell lines for 24 hours at an E:T of 10:1 and the release of IFN-γ and TNF-α were quantified by Luminex multiplex bead technology. Fold elevation of IFN-γ production against KG1a compared with K562 for 26292 and 32716 were 2.3 and 19.1, respectively. Fold elevation of TNF-α production against KG1a compared with K562 for 26292 and 32716 was 5.5 and 16.5, respectively. (F) Pair-matched carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled CD19- or CD123-specific T cells were cocultured with the indicated stimulator cell lines for 96 hours at an E:T of 2:1 and analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE dilution. Unstimulated T cells (filled histograms) were used as baseline T-cell proliferation controls. (G) CFSE-labeled target cells were cocultured with CAR T cells for 5 days in the absence of exogenous cytokines at an E:T ratio of 0.5:1. At the end of the culture, cells were stained using anti-CD3 to distinguish between T cells and CSFE-labeled tumor cells.

CD123 CAR T cells activate multiple effector functions when cocultured with CD123-positive target cells

To examine the effector function of CD123-specific T cells, we measured the secretion of interferon γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) following coculture with various tumor cell lines. T-cell products expressing either CD123 CAR produced both IFN-γ and TNF-α when cocultured with CD123+ target cells, while pair-matched CD19-specific T cells secreted these cytokines only when cocultured with the CD19+ LCL or LCL-OKT3 cell line (Figure 2E). Average values for each factor are presented in Table 1. Additionally, both CD123-specific T-cell lines proliferated when cocultured with either of the CD123+ cell lines LCL, LCL-OKT3, or KG1a, but not with the CD123- K562 cell line (Figure 2F). In contrast, pair-matched CD19 CAR-expressing T cells proliferated only when cocultured with LCL or LCL-OKT3 (Figure 2F). In long-term coculture assays, CD123 CAR T cells effectively eliminated CD123+ target cell lines LCL and KG1a while sparing the CD123− cell line K562, while CD19R T cells eliminated only CD19+ LCL (Figure 2G). Similar results were observed using E:T ratios of 1:1 and 2:1 (data not shown).

Table 1.

In vitro cytokine production by CAR T cells following 24-hour coculture with various target lines

| IFN-γ (pg/mL) | TNF-α (pg/mL) | IL-2 (pg/mL) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCL-OKT3 | LCL | K562 | KG1a | LCL-OKT3 | LCL | K562 | KG1a | LCL-OKT3 | LCL | K562 | KG1a | |

| Mock | 3749.2 | 324.7 | 168.5 | 86.0 | 1826.3 | 57.5 | 45.5 | 45.3 | 806.0 | 134.3 | 134.3 | 134.7 |

| CD19R | 4568.5 | 3850.5 | 116.5 | 129.7 | 1716.3 | 1107.3 | 44.3 | 65.8 | 327.3 | 240.0 | 126.7 | 140.5 |

| 26292 | 3464.8 | 1994.2 | 870.3 | 1978.3 | 1003.0 | 443.3 | 115.8 | 635.8 | 184.0 | 115.7 | 96.0 | 134.3 |

| 32716 | 1860.0 | 654.0 | 106.3 | 2031.2 | 666.2 | 242.2 | 48.5 | 800.2 | 198.3 | 137 | 120.3 | 317.7 |

CD123 CAR T cells activate multiple effector functions when cocultured with primary AML samples

The overexpression of CD123 on primary AML samples is well documented22-24 and confirmed in our study (supplemental Figure 1; Table 2). Multifaceted T cell responses are critical for robust immune responses to infections and vaccines and may also play a role in the antitumor activity of CAR-redirected T cells.25 To investigate the ability CD123 CAR T cells to activate multiple effector pathways against primary AML samples, engineered T cells were cocultured with 3 different AML patient samples (179, 373, and 605) for 6 hours and evaluated for upregulation of CD107a and production of IFN-γ and TNF-α using polychromatic flow cytometry (gating strategy shown in supplemental Figure 2). We observed cell surface mobilization of CD107a in both the CD4 and CD8 compartments of CD123-specific T cells, while pair-matched CD19R T cells showed no appreciable degranulation against primary AML samples (Figure 3A-B, bar graphs). Further, subpopulations of CD107a+ CD123 CAR T cells also produced either IFN-γ, TNF-α, or both cytokines (Figure 3A, pie charts). This multifunctional response was observed for both CD4 and CD8 populations (Figure 3A-B). Additionally, we examined the ability of CAR-engineered T cells to proliferate in response to coculture with a primary AML sample. Both CD123-specific T-cell lines were capable of proliferating following coculture with AML 813 or pre-B ALL 802 samples (Figure 3C). Proliferation was observed for in both the CD4 and CD8 populations (supplemental Figure 3). Predictably, pair-matched CD19-specific T cells proliferated when cocultured with CD19+ pre-B ALL 802 but not when cocultured with AML 813.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and CD123 expression of primary AML patient samples

| AML sample ID | Age/sex | Cytogenetics | Flt3 mutational status | Clinical status at time of sample collection | Sample type | CD123 (RFI)* | CD123% positive† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 179 | 74/M | Intermediate risk, t(1;7), t(14;15) | ND | Relapsed | PB | 428.32 | 99.22 |

| 373 | 47/M | Poor risk, complex abnormalities in 3 cell lines | ND | Relapsed | PB | 1052.83 | 99.66 |

| 493 | 46/F | Intermediate risk, trisomy 8 | ND | Relapsed | PB | 23.98 | 76.80 |

| 519 | 44/F | del(17p), dic (11;7), clonal loss of TP53/17p13.1 | ND | Relapsed | PB | 63.18 | 97.40 |

| 545 | 58/M | Intermediate risk, t(3;6), del(7) | ND | Induction failure | PB | 52.73 | 99.32 |

| 559 | 59/M | Complex abnormalities, massive hyperdiploidy | Negative | Relapsed | Apheresis | 9.30 | 45.0 |

| 605 | 55/M | Normal | Negative | Persistent | PB | 58.48 | 99.91 |

| 722 | 22/M | Intermediate risk, t(14;21), del(9q) | Negative | Untreated | PB | 33.53 | 92.74 |

| 813 | 48/F | Complex abnormalities, trisomy 8, trisomy 21, add(17) | ND | Untreated | PB | 37.19 | 90.93 |

F, female; M, male; ND, not determined; PB, peripheral blood.

RFI is the ratio of the median of the anti-CD123 antibody (clone 9F5)-stained signal to isotype-matched control stain in the CD34+ population.

Gated on CD34+ population.

Figure 3.

Activation of multiple CD4 and CD8 effector functions by CD123-specific CARs following coculture with primary AML samples. Pair-matched CAR-engineered T cells were cocultured for 6 hours with 3 different primary AML patient samples (AML 179, 373, and 605) and analyzed for surface CD107a expression and intracellular IFN-γ or TNF-α production. (A, bar graphs) Percentage of DAPI−CD3+CD8+ EGFRt+ cells expressing CD107a. Data represent mean values + SD. (A, pie charts) The fractions of CD3+CD8+EGFRt+ cells undergoing degranulation and producing IFN-γ and/or TNF-α are plotted in the pie charts. Percentages in each subset are indicated. (B) DAPI−CD3+CD4+EGFRt+ population data from the same experiment as described in panel A. (C) Pair-matched CFSE-labeled CD19- or CD123-specific T cells were cocultured with the indicated stimulator cells for 72 hours at an E:T of 2:1 and analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE dilution in the DAPI−CD3+EGFRt+ population. LCL and K562 cell lines served as positive and negative controls, respectively. Pre-B ALL 802 is a primary patient sample double positive for CD19 and CD123. Quadrant placement is based on unstimulated T cells.

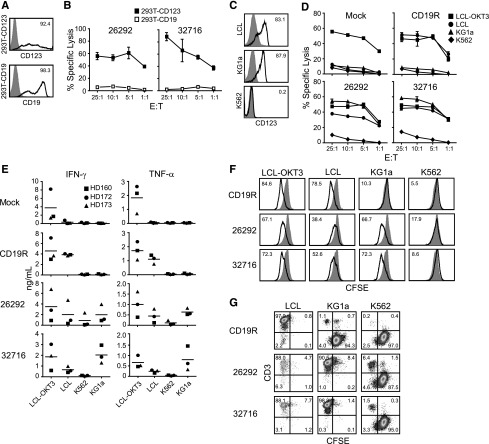

CD123 CAR expressing T cells target primary AML cells in vitro

To evaluate the ability of CD123-specific T cells to kill primary AML cells, we cocultured pair-matched CD19R-CAR or CD123-CAR–expressing T cells with primary CD34-enriched AML patient samples in a 4-hour 51Cr release assay. In contrast to pair-matched CD19R T cells, both CD123 CAR T-cell lines robustly lysed all primary AML patient samples tested (Figure 4A). Additionally, whereas no statistical difference was noted between the cytolytic capabilities of the CD123-CAR–expressing T cells, both CD123-specific T cells demonstrated significantly enhanced cytotoxicity when compared with pair-matched CD19R-CAR T cells (Figure 4B). To investigate if both AML and CB CD123+ cells are susceptible to CAR T-cell–based killing, we examined CD123 levels on viable patient AML cells and CB cells remaining after coculture with CD123 CAR T cells. We found that our 26292scFv-based CD123 CAR effectively eliminated CD123+ primary AML patient cells and CB cells after a 4-hour coculture at E:T 25:1 in both the Lineage−CD34+CD38− compartment and the more mature progenitor cell compartment (Lineage−CD34+CD38+), as evidenced by a lack of CD123 expression on residual viable cells (Figure 4C-D; supplemental Figure 4). Interestingly, in both the stem cell and progenitor compartments, CD123 CAR T cells based on the 32716 scFv eliminated CD123high cells, while CD123low target cells survived the coculture (Figure 4C-D; supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Primary AML cells are specifically targeted by CD123 specific T cells. (A) Pair-matched CD19 or CD123-specific T cells were cocultured for 4 hours with 51Cr labeled CD34+ primary AML samples at an E:T of 25:1. Pre-B ALL 802 is a primary patient sample double positive for CD19 and CD123. Data represents mean values of triplicate wells + SD (B) Specific lysis of AML blasts from the 3 primary AML patient samples in panel A. Data represent mean values ± SEM. *P < .05 and **P < .0005 using the unpaired Student t test comparing 26292 and 32716 to CD19R. (C-D) CD34-enriched primary AML or CB cells were cocultured with CAR T cells or left untreated for 4 hours prior to flow cytometric analysis. Percentages in each quadrant are indicated. For CD123 histograms (second and third rows), the y-ordinate scale was adjusted according to the number of events captured and the relative fluorescence (RFI) index is indicated. The RFI is the ratio of the median of the anti-CD123 antibody (clone 9F5)-stained signal to isotype-matched control stain. Gates were placed according to fluorescence-minus-one controls.

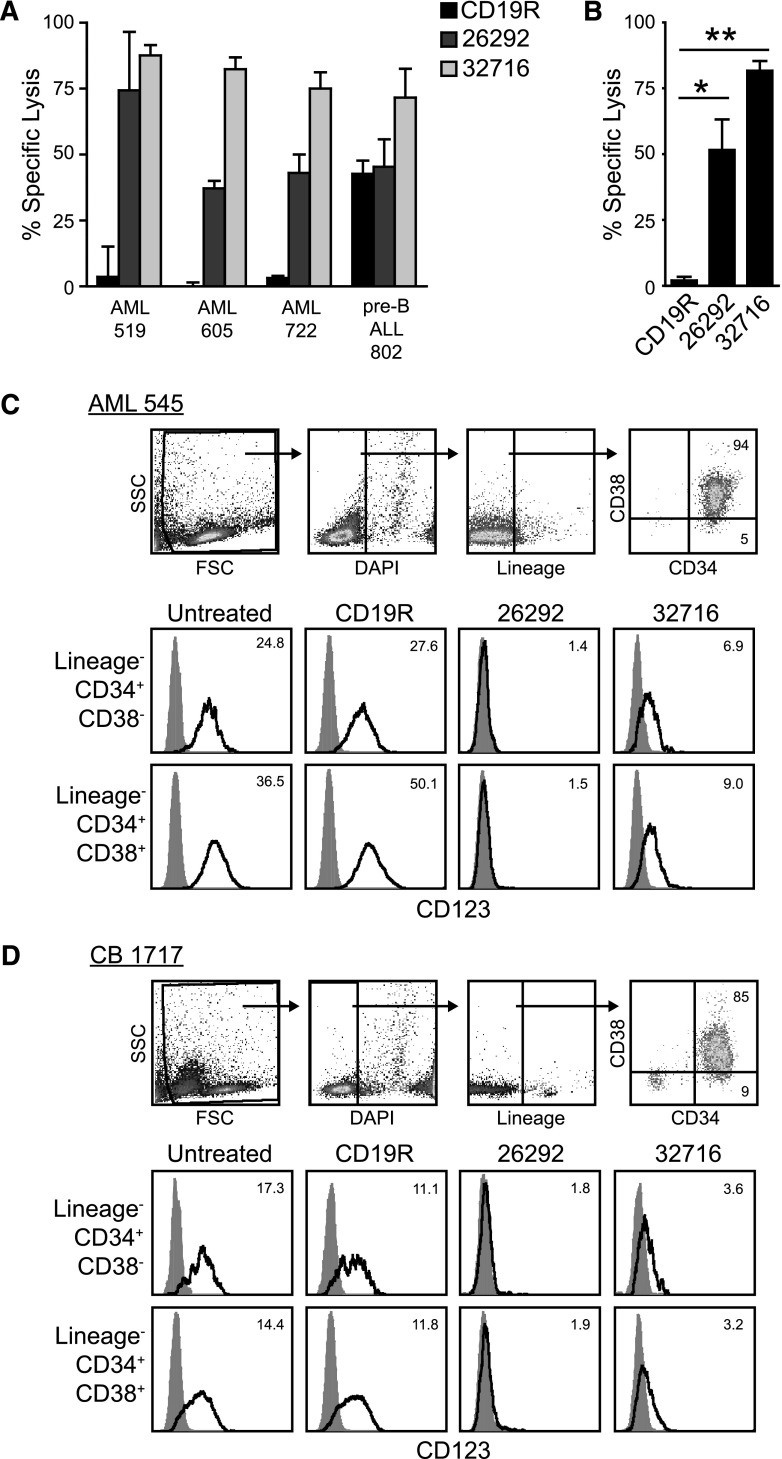

CD123-specific T cells do not eliminate colony formation by CB cells in vitro

Given that CD123 is expressed on common myeloid progenitors (CMPs),26 we investigated the effect of our engineered T cells on the colony-forming ability of CD34-enriched normal CB samples. Interestingly, myeloid and erythroid colony formation by CB samples was not eliminated following a 4-hour coculture with CD123-CAR–expressing T cells at an E:T of 25:1 (Figure 5A-B). Next, we examined the ability of CD123-specific T cells to inhibit the growth of primary clonogenic AML cells in vitro. Both CD123 CAR T-cell lines significantly decreased the formation of leukemic colonies compared with pair-matched CD19R T cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

The effect of CD123-CAR–expressing T cells on normal and leukemic progenitor cells in vitro. (A-B) CD34+ CB cells (n = 3) were CD34-immunomagnetically selected and cocultured with either CD19- or CD123-specific pair-matched T cells from a healthy donor or media alone (untreated) for 4 hours at an E:T of 25:1. The cells were then plated in semisolid methylcellulose progenitor culture for 14 to 18 days and scored for the presence of BFU-E (A), CFU-GM (B) and colonies. Colony numbers (left) and normalized colony formation percentages (right) are presented. Percentages are normalized to CD19-specific T cell controls. Data represent mean values + SEM for 3 different CB samples. (C) CD34+ primary AML patient samples (AML 493, 519, or 545) were immunomagnetically selected and cocultured with either CD19 or CD123-specific CAR T cells from a healthy donor or media alone (untreated) for 4 hours at an E:T of 25:1. The cells were then plated in semisolid methylcellulose progenitor culture for 14 to 18 days and scored for the presence of leukemia colony-forming units (CFU-L). Colony numbers (left) and normalized colony formation percentages (right) are presented. Percentages are normalized to CD19-specific T cell controls. Data represent mean values + SEM for 3 different primary AML patient samples. *P < .05 using the unpaired Student t test comparing 26292 and 32716 to CD19R.

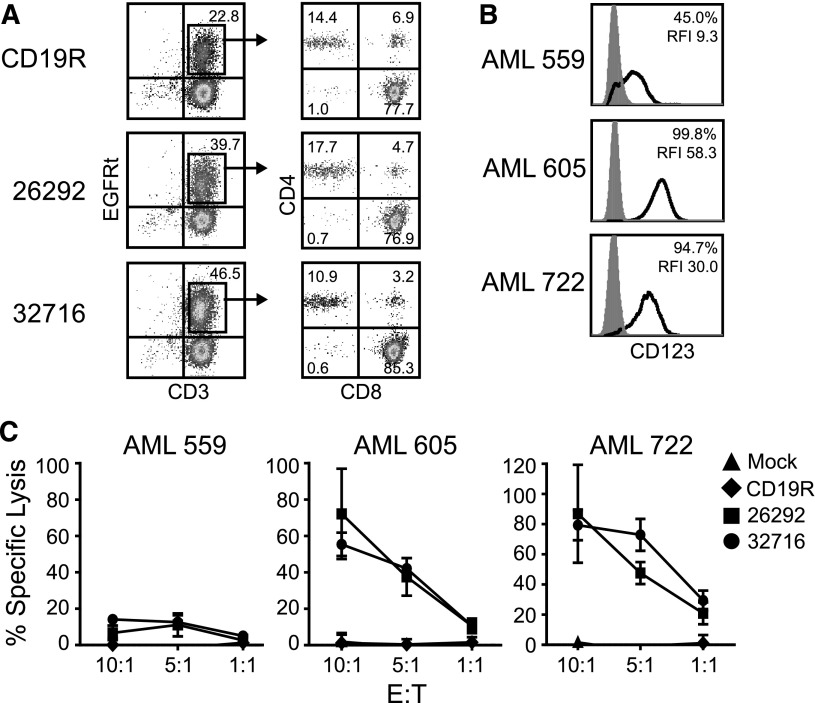

T cells from AML patients can be genetically modified to express CD123 CARs and specifically target autologous tumor cells

AML-patient–derived T cells are known to poorly repolarize actin and form defective immune synapses with autologous blasts.27 Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, CAR-expressing T cells derived from AML patients have yet to be described. Therefore, we examined if T cells from AML patients could be genetically modified to express CD123 CARs. Cryopreserved PBMCs (AML 605 and AML 722) or apheresis product (AML 559) were CD3/CD28 bead stimulated and lentivirally transduced to express either of the CD123 CARs or a CD19R control CAR. All 3 patient-sample–derived T cells expressed the 26292 CAR (40% to 65% transduction efficiency), the 32716 CAR (46% to 70% transduction efficiency), and the CD19R CAR (23% to 37% transduction efficiency). A representative example of the phenotype of AML-patient–derived CAR T cells is shown in Figure 6A. Next, we investigated the cytolytic potential of AML-patient–derived CAR T cells against autologous CD34-enriched target cells in a 4-hour 51Cr release assay. All of the autologous CD34-enriched cells expressed CD123, albeit at varying percentages and intensities (Figure 6B). T cells derived from AML 605 and 722 efficiently lysed autologous blasts, while T cells derived from AML 559 displayed low levels of autologous blast lysis likely due to the low and heterogeneous expression of CD123 on AML 559 blasts (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

CD123-CAR–redirected T cells derived from AML patients specifically lyse autologous blasts in vitro. (A) T cells from 3 AML patients were lentivirally transduced to express either CD19R, 26292, or 32716 CARs. Shown are T cell lines from AML 722 19 days posttransduction. (B) CD123 expression on target cells used in 51Cr release assay. The percentage of CD123+ cells and the RFI of each sample is indicated. (C) Results of 4-hour autologous killing assays using T cells engineered from 3 AML patient samples as effectors and 51Cr-labeled autologous CD34-enriched blasts as target cells. Data represent mean values of triplicate wells ± SD.

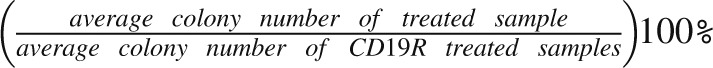

CD123 CAR T cells exhibit antileukemic effects in an in vivo model of systemic AML

To examine the in vivo antileukemic activity of CD123 CAR T cells, we developed a xenogeneic model of systemic AML using the KG1a leukemic cell line engineered to express the eGFP and ffLuc reporter genes (KG1a-eGFP-ffLuc). Intravenous injection of KG1a cells results in orthotopic engraftment of AML in the bone marrow (data not shown) and at later stages of disease progression leukemia can be detected in the peripheral blood. Mice inoculated intravenously with KG1a-eGFP-ffLuc cells were treated 5 days later with a single intravenous injection of CAR+ T cells (Figure 7A) and tumor progression was monitored by bioluminescence imaging. Control mice treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or CD19R T cells had a rapid progression of leukemia. By comparison, CD123-CAR–treated mice displayed a significant decrease in systemic leukemic burden as evidenced by bioluminescent imaging (Figure 7B-C) and flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood at day 32 after tumor inoculation (Figure 7D-E). This resulted in a significant increase in survival for mice treated with CD123 CAR T cells compared with both CD19R-treated (P = .017) and PBS-treated (P = .035) groups (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

CD123 CAR T cells exhibit antileukemic effects in vivo. Mice were sublethally irradiated with 300 cGy from a 137Cs γ-irradiator 24 hours prior to intravenous transplantation of 0.5 × 106 KG1a-GFP-firefly luciferase cells. Five days later, mice received a single intravenous injection of 5.0 × 106 CAR+ T cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of CAR-expressing T cells prior to use in vivo. Percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. (B) Bioluminescent imaging prior to T-cell treatment (day 4), on day 12, and on day 33 following KG1a-GFP-firefly luciferase transplantation. (C) Bioluminescent signal for each treatment group over time. Dotted line represents day of T-cell treatment. Data represent mean values of each group ± SD. Results represent pooled data from 2 separate experiments. PBS n = 3; CD19R, 26292, 32716 n = 6. (D) Representative flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood 32 days after leukemia transplant. Percentage of viable human CD45+GFP+ KG1a cells is indicated. (E) Summary of leukemic cell engraftment in mouse peripheral blood 32 days after leukemia transplant. The percentage of viable human CD45+GFP+ KG1a cells is indicated. Each symbol indicates 1 mouse; bars represent mean values, and mean values for each group are indicated. (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of survival for each group (PBS n = 3, CD19R n = 4, CD123-specific n = 10). Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests were used to perform statistical analyses of survival between groups. *P < .05.

Discussion

Although current treatment regimens for AML can achieve complete responses in select patients, many patients will eventually relapse, underscoring the need for novel therapeutics that may lead to more durable responses.2 Various AML-targeting immunotherapies, including antigen specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes, alloreactive natural killer cells, and dendritic cell vaccines, are currently being developed and have shown promising results.28 To this end, we aimed to develop a CAR that would redirect T-cell specificity to selectively target AML cells in an HLA-independent manner. Here, we show that T cells expressing either of 2 CD123-specific CARs can specifically lyse CD123-expressing cell lines or unbiasedly selected primary AML patient samples, activate multiple effector functions in an antigen-specific manner in vitro, and display antileukemic activity against systemic AML in vivo, thus demonstrating that both epitopes are potential targets for treatment. No major differences were observed between the CD123-CAR–engineered T cell lines with respect to target cell killing, cytokine secretion, proliferation, or in vivo antitumor activity. One possible explanation for this is that the binding affinities of the CD123-specific scFvs used in the CD123-CARs are in the nanomolar range and differ by less than 3-fold, and thus no significant advantage in target antigen binding is conferred by either scFv.19

The expression of multiple cell surface antigens on AML cells has been well documented.4,22,29 In this work, we have engineered CAR T cells to target CD123, a cell surface receptor highly expressed by primary AML cells. Expression of CD123 is absent on T cells, predominantly restricted to cells of the myeloid lineage,30 and displays limited expression on hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).22,23,31,32 Therapeutics specific for CD123 have displayed favorable safety profiles in phase 1 trials (ClinicalTrials.gov ID #NCT00401739 and #NCT00397579). Together, these observations make CD123 an attractive target for CAR-mediated T-cell therapy. Other AML antigens may also be potential targets for CAR-expressing T cells. For instance, the epithelial mucin, MUC1, is expressed on primary AML cells and has been shown to be an attractive immunotherapy target using MUC1-specific T cells.33 Folate receptor β is an intriguing target on AML cells given its upregulatable expression by all-trans retinoic acid and histone deacetylase inhibitors.34 The AML-associated antigen TIM-3 is another target, but its expression on T-cell subsets35 may result in the autolysis of genetically modified cells. The CD33 differentiation antigen is also predominately expressed on myeloid cells and immunotherapies targeting CD33 such as gemtuzumab ozogamicin, CD33/CD3 bispecific T-cell–engaging antibodies, and a CD33 CAR are currently used in clinical and preclinical settings.17,36,37 Similar to TIM-3, CD33 is expressed on a subset of T cells, making it a nonideal target for a CAR-based therapy.38 Additionally, the antileukemic activity of CD33-targeting therapies was often accompanied by slow recovery of hematopoiesis and cytopenias, likely the result of CD33 expression on long-term self-renewing normal HSCs.39 Further, hepatotoxicities are a common side effect of CD33-targeted treatments and are possibly due to the unintended targeting of CD33+ Kupffer cells.40

While clinical experience provides evidence for the safety of targeting CD123 with either antibody or immunotoxin for the treatment of AML, these therapies have thus far failed to induce responses in the vast majority of treated patients. The CD123-CAR–expressing T cells generated here displayed potent cytolytic capacity in vitro against CD123+ cell lines and primary AML samples, including those with poor-risk features. Additionally, we demonstrate that both primitive Lineage−CD34+CD38−CD123+ and more mature Lineage−CD34+CD38+CD123+ cells from primary AML patient samples were susceptible to CD123 CAR T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity. In 51Cr release assays, CD123 CAR T cells using the 32716-based scFv are trending toward a significant difference (P = .0698 using unpaired Student t test) in killing primary AML patient samples compared with 26292-based CAR T cells. Interestingly, in our degranulation assay, both CD123 CAR T cells degranulated similarly against AML 605 (74% CD107a+CD3+CD8+EGFRt+ for 26292 and 65% CD107a+CD3+CD8+EGFRt+ for 32716). Additionally, we observed that after a 4-hour coculture, 26292-based CAR T cells more efficiently eliminated CD123+ cells from primary AML patient samples when compared with the 32716-based CAR T cells. This result was also true for CB cells. Collectively, our data demonstrate that AML patient samples that exhibited high-risk features at diagnosis and/or chemoresistance were sensitive to CD123 CAR killing, similar to what we observed in experiments using CD123+ cell lines.

Multifunctional T-cell responses correlate with the control of virus infection and may be key in an antitumor CAR T-cell response.41 Indeed, patients responsive to CD19 CAR T-cell therapy have detectable ex vivo CD19-specific T cell activity posttherapy (ie, degranulation, cytokine secretion, or proliferation).11,12,14 Here, we demonstrate the functionality of CD123-CAR expressing T cells by analyzing the upregulation of CD107a, production of inflammatory cytokines, and proliferation of CD123-specific T cells in response to both CD123+ cell lines and primary AML samples. While CD123 CAR T cells proliferated in response to CD123+ target cells, this proliferation was limited and likely due to the CD123 CAR T cells going through multiple rounds of the rapid expansion protocol prior to being used in the proliferation assays.

Importantly, we observed multifunctionality in subsets of both the CD4+ and CD8+ compartments, which may promote sustained antileukemic activity and boost antileukemic activity within the tumor microenvironment.42 Although polyfunctionality was modest and observed in a subset of CD123 CAR T cells, the inclusion of other costimulatory domains such as 4-1BB, and the use of “younger” less differentiated T cells may further augment CD123 CAR responses and are an area of active research.8,43

An outstanding question is the toxicity to CMPs associated with CD123 CAR T-cell therapy. Expression of CD123 on Lineage−CD34+CD38+ cells is documented for CMPs26 and thus a possible target of CD123 CAR T cells. To address this question, we assessed CFU formation of CB cells treated with CD123 CAR T cells. Although we observed an approximately 50% decrease in CFU-GM formation, a key finding in our study is that normal progenitor colony formation was not abolished when CD34+ CB cells were cocultured with CD123-specific T cells even at an E:T of 25:1. Another question is the effect of CD123 CAR T cells on the HSC. Although CD123 expression is limited on HSCs from normal adult bone marrow,22,23,31,32 we recognize that further experimentation is needed to characterize the potential impact on long-term hematopoiesis that CD123 CAR T cells may have. In order to control unwanted off-target toxicities, we have included EGFRt in our lentiviral construct to potentially allow for ablation of CAR-expressing T cells.44 Other strategies to modulate CAR T cell activity such as the inducible caspase-9 apoptosis switch45 or electroporation of messenger RNA to allow for transient CAR expression46 are also of high interest. Additionally, an ideal setting for the use of autologous CD123 CAR T cells clinically may be in the context of allogeneic HSCT where a compatible stem cell donor has been identified prior to infusion of CAR T cells. A similar treatment plan has been used successfully to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients with CD19 CAR T cells.47

Significantly, we demonstrate that cryopreserved PBMCs from AML patients with active disease can be genetically modified to express CD123 CARs and exhibit potent cytolytic activity against autologous leukemic blasts in 2 of 3 samples we examined. While CD123-CAR–expressing T cells from AML 559 failed to lyse autologous blasts which expressed low levels of CD123, these CAR T cells did lyse CD123+ LCL and KG1a cell lines (data not shown), suggesting that the generated T cells have the potential to target CD123-expressing target cells. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that AML-patient–derived T cells can be engineered to express a CAR and exhibit redirected antigen-specific cytotoxicity against autologous blasts.

Importantly, we showed that a single injection CD123 CAR T cells had a demonstrable in vivo antileukemic effect in a systemic xenogenic model of human AML. The minimally differentiated KG1a cell line used in this model system does not express costimulatory molecules CD80/CD86, much like undifferentiated primary AML patient samples.48 The antileukemic effect observed in our studies is comparable with what is often seen in xenogeneic models of acute leukemia void of tumor-derived costimulation, using either single or multiple infusions of CAR T cells.9,49 The in vivo potency of our CD123 CAR T cells may be further augmented by using a less differentiated memory T-cell subset or by altering several features of the CAR including scFv affinity, linker length, and intracellular costimulatory domain (s), all of which have been shown to play key roles in CAR T-cell potency.8,10,43,50

Recently, Tettamanti, Marin, et al have demonstrated that cytokine-induced killer cells expressing a first-generation CD123 CAR exhibit potent cytolytic activity against AML cell lines and primary patient samples while sparing normal hematopoietic progenitors in vitro.18 Our data now demonstrates that second-generation CD123 CARs T cells can distinguish between CD123+ and CD123− cells and activate multiple T-cell effector functions against a panel of poor-risk primary AML patient samples. These CD123-specific T cells did not eliminate normal progenitor colony formation but considerably reduced the growth of clonogenic myeloid leukemic progenitors in vitro. Further, we demonstrate that T cells derived from AML patients can be genetically modified to express CD123-specific CARs and lyse autologous blasts in vitro. Finally, we demonstrate that our CD123 CAR T cells exhibit potent antileukemia effects in vivo. Therefore, CD123 CAR T cells are promising candidates for future immunotherapy of AML.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Don Diamond, Dr Edwin Emanuel, Dr Allen Lin, Dr Sandra H. Thomas, and Dr John Zaia for their sharing of equipment and helpful comments.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants P50 CA107399, P30 CA33572, and P01 CA030206, and National Center for Research Resources grant M01 RR0004, the H.N. and Frances C. Berger Foundation, the Lymphoma Research Foundation, the Marcus Foundation, the Parsons Foundation, the Skirball Foundation, the Tim Lindenfelser Lymphoma Research Fund, and the Tim Nesvig Lymphoma Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: A.M. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; C.D.S. and T.M. designed and performed research and analyzed data; C.E.B., X.W., and L.E.B. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; L.H. and B.A. designed and performed research and analyzed data; W.-C.C. designed research and analyzed data; W.B. performed research; B.C. designed research and analyzed data; M.J. shared unpublished data; R.S. designed research and analyzed data; J.R.O. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; M.C.J. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; R.B. contributed reagents, designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; and S.J.F. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.C.J. is an inventor of licensed intellectual property and a cofounder/equity of ZetaRx Biosciences. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen J. Forman, Hematology & Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1500 East Duarte Rd Duarte, CA 91010; email: sforman@coh.org.

References

- 1.Eaves CJ, Humphries RK. Acute myeloid leukemia and the Wnt pathway. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2326–2327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1003522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Döhner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, et al. European LeukemiaNet. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115(3):453–474. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-235358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majeti R. Monoclonal antibody therapy directed against human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Oncogene. 2011;30(9):1009–1019. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikushige Y, Shima T, Takayanagi S, et al. TIM-3 is a promising target to selectively kill acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(6):708–717. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jena B, Dotti G, Cooper LJ. Redirecting T-cell specificity by introducing a tumor-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Blood. 2010;116(7):1035–1044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-043737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper LJ, Topp MS, Serrano LM, et al. T-cell clones can be rendered specific for CD19: toward the selective augmentation of the graft-versus-B-lineage leukemia effect. Blood. 2003;101(4):1637–1644. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochenderfer JN, Feldman SA, Zhao Y, et al. Construction and preclinical evaluation of an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Immunother. 2009;32(7):689–702. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ac6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milone MC, Fish JD, Carpenito C, et al. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol Ther. 2009;17(8):1453–1464. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brentjens RJ, Santos E, Nikhamin Y, et al. Genetically targeted T cells eradicate systemic acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 Pt 1):5426–5435. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudecek M, Lupo-Stanghellini MT, Kosasih PL, Sommermeyer D, Jensen MC, Rader C, Riddell SR. Receptor affinity and extracellular domain modifications affect tumor recognition by ROR1-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(12):3153–3164. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brentjens RJ, Rivière I, Park JH, et al. Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood. 2011;118(18):4817–4828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384388. 19(12):2709-2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savoldo B, Ramos CA, Liu E, et al. CD28 costimulation improves expansion and persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in lymphoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(5):1822–1826. doi: 10.1172/JCI46110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, Katz S, Grupp SA, Bagg A, June CH. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(95):95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Till BG, Jensen MC, Wang J, et al. CD20-specific adoptive immunotherapy for lymphoma using a chimeric antigen receptor with both CD28 and 4-1BB domains: pilot clinical trial results. Blood. 2012;119(17):3940–3950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peinert S, Prince HM, Guru PM, et al. Gene-modified T cells as immunotherapy for multiple myeloma and acute myeloid leukemia expressing the Lewis Y antigen. Gene Ther. 2010;17(5):678–686. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutour A, Marin V, Pizzitola I, et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor effect of anti-CD33 chimeric receptor-expressing EBV-CTL against CD33 acute myeloid leukemia. Adv Hematol. 2012;2012:683065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Tettamanti S, Marin V, Pizzitola I, et al. Targeting of acute myeloid leukaemia by cytokine-induced killer cells redirected with a novel CD123-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(3):389–401. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du X, Ho M, Pastan I. New immunotoxins targeting CD123, a stem cell antigen on acute myeloid leukemia cells. J Immunother. 2007;30(6):607–613. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318053ed8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia R, McGlave PB, Dewald GW, Blazar BR, Verfaillie CM. Abnormal function of the bone marrow microenvironment in chronic myelogenous leukemia: role of malignant stromal macrophages. Blood. 1995;85(12):3636–3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahlon KS, Brown C, Cooper LJ, Raubitschek A, Forman SJ, Jensen MC. Specific recognition and killing of glioblastoma multiforme by interleukin 13-zetakine redirected cytolytic T cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):9160–9166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan CT, Upchurch D, Szilvassy SJ, et al. The interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain is a unique marker for human acute myelogenous leukemia stem cells. Leukemia. 2000;14(10):1777–1784. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin L, Lee EM, Ramshaw HS, et al. Monoclonal antibody-mediated targeting of CD123, IL-3 receptor alpha chain, eliminates human acute myeloid leukemic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muñoz L, Nomdedéu JF, López O, et al. Interleukin-3 receptor alpha chain (CD123) is widely expressed in hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2001;86(12):1261–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(4):247–258. doi: 10.1038/nri2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manz MG, Miyamoto T, Akashi K, Weissman IL. Prospective isolation of human clonogenic common myeloid progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(18):11872–11877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172384399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Dieu R, Taussig DC, Ramsay AG, et al. Peripheral blood T cells in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients at diagnosis have abnormal phenotype and genotype and form defective immune synapses with AML blasts. Blood. 2009;114(18):3909–3916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kadowaki N, Kitawaki T. Recent advance in antigen-specific immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:104926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Majeti R, Chao MP, Alizadeh AA, et al. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 2009;138(2):286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato N, Caux C, Kitamura T, et al. Expression and factor-dependent modulation of the interleukin-3 receptor subunits on human hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1993;82(3):752–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du W, Li XE, Sipple J, Pang Q. Overexpression of IL-3Rα on CD34+CD38- stem cells defines leukemia-initiating cells in Fanconi anemia AML. Blood. 2011;117(16):4243–4252. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taussig DC, Pearce DJ, Simpson C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106(13):4086–4092. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brossart P, Schneider A, Dill P, et al. The epithelial tumor antigen MUC1 is expressed in hematological malignancies and is recognized by MUC1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2001;61(18):6846–6850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi H, Ratnam M. Synergistic induction of folate receptor beta by all-trans retinoic acid and histone deacetylase inhibitors in acute myelogenous leukemia cells: mechanism and utility in enhancing selective growth inhibition by antifolates. Cancer Res. 2006;66(11):5875–5882. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golden-Mason L, Palmer BE, Kassam N, et al. Negative immune regulator Tim-3 is overexpressed on T cells in hepatitis C virus infection and its blockade rescues dysfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Virol. 2009;83(18):9122–9130. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00639-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walter RB, Appelbaum FR, Estey EH, Bernstein ID. Acute myeloid leukemia stem cells and CD33-targeted immunotherapy. Blood. 2012;119(26):6198–6208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-325050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aigner M, Feulner J, Schaffer S, et al. T lymphocytes can be effectively recruited for ex vivo and in vivo lysis of AML blasts by a novel CD33/CD3-bispecific BiTE((R)) antibody construct. Leukemia. 2013 doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.341. 7(5):1107-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernández-Caselles T, Martínez-Esparza M, Pérez-Oliva AB, et al. A study of CD33 (SIGLEC-3) antigen expression and function on activated human T and NK cells: two isoforms of CD33 are generated by alternative splicing. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79(1):46–58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0205096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sievers EL, Larson RA, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Mylotarg Study Group. Efficacy and safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3244–3254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsimberidou AM, Giles FJ, Estey E, O’Brien S, Keating MJ, Kantarjian HM. The role of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in acute leukaemia therapy. Br J Haematol. 2006;132(4):398–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Appay V, Douek DC, Price DA. CD8+ T cell efficacy in vaccination and disease. Nat Med. 2008;14(6):623–628. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moeller M, Kershaw MH, Cameron R, et al. Sustained antigen-specific antitumor recall response mediated by gene-modified CD4+ T helper-1 and CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(23):11428–11437. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, et al. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/nm.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Chang WC, Wong CW, et al. A transgene-encoded cell surface polypeptide for selection, in vivo tracking, and ablation of engineered cells. Blood. 2011;118(5):1255–1263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Straathof KC, Pulè MA, Yotnda P, et al. An inducible caspase 9 safety switch for T-cell therapy. Blood. 2005;105(11):4247–4254. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoon SH, Lee JM, Cho HI, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy using human peripheral blood lymphocytes transferred with RNA encoding Her-2/neu-specific chimeric immune receptor in ovarian cancer xenograft model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009;16(6):489–497. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(177):177ra138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Whiteway A, Corbett T, Anderson R, Macdonald I, Prentice HG. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules on acute myeloid leukaemia blasts may effect duration of first remission. Br J Haematol. 2003;120(3):442–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deniger DC, Switzer K, Mi T, et al. Bispecific T-cells expressing polyclonal repertoire of endogenous γδ T-cell receptors and introduced CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Mol Ther. 2013;21(3):638–647. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berger C, Jensen MC, Lansdorp PM, Gough M, Elliott C, Riddell SR. Adoptive transfer of effector CD8+ T cells derived from central memory cells establishes persistent T cell memory in primates. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(1):294–305. doi: 10.1172/JCI32103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.