Background: The E3 ubiquitin ligase ASB2α triggers proteasomal degradation of filamins and regulates cell spreading and differentiation.

Results: ASB2α targets filamin's calponin homology 1 (CH1) domain, and mutations in CH1 render filamin ASB2α-resistant.

Conclusion: ASB2α-resistant filamins protect cells from ASB2α-mediated inhibition of spreading.

Significance: ASB2α exerts its effect on cell spreading via targeted degradation of filamins.

Keywords: Actin, Cell Biology, Cytoskeleton, E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Filamin, Calponin Homology Domain, Stress Fiber

Abstract

Filamins are actin-binding and cross-linking proteins that organize the actin cytoskeleton and anchor transmembrane proteins to the cytoskeleton and scaffold signaling pathways. During hematopoietic cell differentiation, transient expression of ASB2α, the specificity subunit of an E3-ubiquitin ligase complex, triggers acute proteasomal degradation of filamins. This led to the proposal that ASB2α regulates hematopoietic cell differentiation by modulating cell adhesion, spreading, and actin remodeling through targeted degradation of filamins. Here, we show that the calponin homology domain 1 (CH1), within the filamin A (FLNa) actin-binding domain, is the minimal fragment sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation. Combining an in-depth flow cytometry analysis with mutagenesis of lysine residues within CH1, we find that arginine substitution at each of a cluster of three lysines (Lys-42, Lys-43, and Lys-135) renders FLNa resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation without altering ASB2α binding. These lysines lie within previously predicted actin-binding sites, and the ASB2α-resistant filamin mutant is defective in targeting to F-actin-rich structures in cells. However, by swapping CH1 with that of α-actinin1, which is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation, we generated an ASB2α-resistant chimeric FLNa with normal subcellular localization. Notably, this chimera fully rescues the impaired cell spreading induced by ASB2α expression. Our data therefore reveal ubiquitin acceptor sites in FLNa and establish that ASB2α-mediated effects on cell spreading are due to loss of filamins.

Introduction

ASB2α5 (named for ankyrin repeat-containing protein with a suppressor of cytokine signaling box-2) was initially identified as a retinoic acid-response gene in myeloid leukemia cells, where it was shown to induce growth inhibition and chromatin condensation, events critical to retinoic acid-induced differentiation (1, 2). ASB2α is the specificity subunit of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (3, 4) and contains an N-terminal region followed by 15 predicted ankyrin repeats and a C-terminal suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) box (Fig. 1A). The SOCS box mediates interaction with a cullin family member (Cullin 5) and RING finger proteins (Rbx1/2) by interacting with elongin BC to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (3, 4). ASB2α was therefore proposed to regulate myeloid cell proliferation and differentiation by targeting a specific regulatory protein, or proteins, for degradation (1, 3).

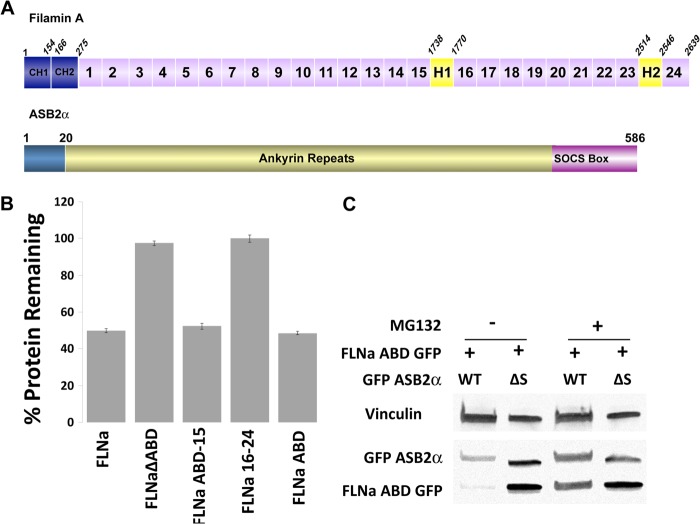

FIGURE 1.

ABD of FLNa is targeted for proteasomal degradation by ASB2α. A, schematic representation of FLNa and ASB2α. Each FLNa dimer is composed of an actin-binding domain (ABD) containing two calponin homology domains (CH1 and CH2) followed by 24 Ig-like repeats (IgFLN1–24). The repeats are interrupted by two hinge regions, H1 and H2, and mediate interaction with a majority of filamin binding partners. Filamins dimerize via IgFLN24 and form a flexible V-shaped structure. ASB2α is composed of an N-terminal region followed by 15 predicted ankyrin repeats and a C-terminal SOCS box. The SOCS box mediates interaction with a cullin family member (Cullin 5) and RING finger proteins (Rbx 1/2) by interacting with elongin BC to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. B, CHO cells transiently expressing FLNa GFP, FLNaΔABD GFP, FLNaABD-15 GFP, FLNa16–24 GFP, and FLNaABD GFP were transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS. 48 h after transfection, cells were detached and washed with PBS, and the GFP intensity of dsRed-expressing cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Bar chart depicts mean percentage of GFP-tagged protein remaining ± S.E. in dsRed-ASB2α-expressing cells normalized to levels in dsRed-ASB2αΔS-expressing cells (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Data are from at least seven independent experiments. C, CHO cells were co-transfected with FLNaABD GFP and GFP-ASB2α or GFP-ASB2αΔS. 30 h after transfection cells were untreated or treated with 5 μm MG132 for 18 h. 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed and immunoblotted using anti-GFP. Vinculin staining was used as a loading control.

We have shown that ASB2α expression triggers rapid proteasomal degradation of filamins in various cell types (5–7). Furthermore, retinoic acid-induced expression of ASB2α correlates with filamin down-regulation in myeloid leukemia cells induced to differentiate (5), and knock down of endogenous ASB2α delays filamin degradation and differentiation (5). Loss of filamins may therefore play a key role in hematopoietic cell differentiation.

Filamins are homodimeric actin-binding and cross-linking proteins that operate in a diverse range of cellular functions, including cell motility, maintenance of cell shape, differentiation, transcriptional regulation, and mechano-transduction (8). The mammalian filamin family consists of three highly homologous isoforms, FLNa, FLNb, and FLNc, of which FLNa is the most abundant and widely distributed (9). Each filamin subunit is composed of an N-terminal actin-binding domain (ABD), followed by 24 Ig-like repeats (IgFLN1–24) (Fig. 1A). The Ig-like repeats are interrupted by two hinge regions, H1 and H2, and mediate interaction with the majority of filamin-binding partners (10–12). Filamins dimerize via IgFLN24 and form a flexible V-shaped structure that regulates organization of the actin cytoskeleton, anchors transmembrane proteins, and scaffolds a wide range of signaling molecules (9, 11, 13, 14).

In addition to a possible role in hematopoietic cell differentiation, filamins have also been implicated in differentiation of other cell types as follows: filamin down-regulation correlates with myoblast differentiation (15) and FLNa knockdown in human mesenchymal stem cells significantly increases chondrocyte differentiation (16). In keeping with their important roles in cytoskeletal organization, signaling and differentiation filamins are essential to mammalian development (11, 12). Mutations in the most widely expressed human filamin, FLNa, result in a neuronal migration disorder and cardiovascular defects as well as a broad range of other congenital malformations, affecting craniofacial structures, skeleton, viscera, and urogenital tract (17–20). Mutations in FLNb lead to severe skeletal malformations and impaired differentiation of chondrocyte precursors (21, 22), whereas mutations in FLNc result in myofibrillar myopathy, muscular dystrophy, and defective differentiation of muscle cells (23–25).

As described above, the known roles of filamins in cytoskeletal organization, signaling, and differentiation, coupled with the clear evidence that ASB2α targets filamins for degradation, suggest that ASB2α-mediated filamin depletion is likely to be central to ASB2α's effects on cell adhesion, spreading, and differentiation. Moreover, a recent study using ASB2α conditional knock-out mice supports roles for ASB2α and FLNa in dendritic cell spreading and maturation (26). However, other ASB2α substrates have recently been reported, including Janus kinases (27, 28) and mixed lineage leukemia (29). A definitive test of filamins' roles in ASB2α function requires a better understanding of ASB2α-mediated degradation and identification of functional ASB2α-resistant filamin mutants. In our previous studies, we provided insight into the mechanism by which ASB2α targets filamins for degradation, and we identified the ABD of filamin as sufficient and necessary for ASB2α-mediated degradation (7). We now map the ASB2α target region to the calponin homology domain 1 (CH1) in the FLNa actin-binding domain and identify a specific cluster of lysine residues in CH1 that are required for FLNa proteasomal degradation. We use this information to generate point mutant or chimeric FLNa that is resistant to ASB2α allowing us to show that cell spreading defects associated with ASB2α expression can be fully reversed by restoring FLNa expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and DNA Constructs

Polyclonal anti-GFP (Rockland), secondary anti-goat Alexa-680 (Invitrogen), and phalloidin Alexa-568-conjugated (Invitrogen) were purchased. 1 mg/ml fibronectin solution and MG132 were purchased from Sigma. Full-length FLNa-GFP, FLNaABD (aa 1–275)-GFP, FLNaΔABD (aa 276–2647)-GFP, and α-actinin1 ABD (aa 1–253)-GFP have been described previously (7). FLNaCH1 (aa 1–154) and FLNaCH2 (aa 156–275) were generated using polymerase chain reaction and subcloned into GFP pCDNA3, a modified version of pCDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen). CH1α-CH2f (aa 1–133 of α-actinin1 plus aa 155–275 of FLNa) and CH1f-CH2α (aa 1–165 of FLNa plus aa 146–253 of α-actinin1) both comprising the linker region of FLNa (aa 155–165) were generated by overlap extension PCR and subcloned into GFP pCDNA3. CH1α-FLNa (aa 1–133 of α-actinin1 plus aa 155–2647 of FLNa)-GFP pCDNA3 was generated by swapping CH1 of FLNa with CH1 of α-actinin1 in the FLNa-GFP pCDNA3 construct. FLNaABD Lys/Arg containing 13 lysine to arginine mutations (amino acids 33, 42, 43, 58, 62, 87, 88, 92, 120, 127, 135, 164, and 165) and various permutations of FLNaABD Lys/Arg mutants were generated by serial rounds of QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). FLNaABD-GFP pCDNA3 was used as the starting template for the first round of QuikChange. GST-FLNaABD was a gift from J. Ylänne (University of Jyväskylä, Finland) (30). GST-FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R was generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis. dsRed-ASB2α and dsRed-ASB2αΔS expression constructs were described previously (5, 7, 31).

Cell Lines, Culture Conditions, and Transfection

CHO cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) containing 9% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biological), sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen), nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). HeLa and HT1080 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 9% FBS, sodium pyruvate and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For transfection, cells were either plated at 50% confluence and transfected 24 h after plating or transfected in suspension using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or PEI (Polysciences, Inc.).

Immunofluorescence

Cells plated on fibronectin-coated (5 μg/ml) coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, for 15 min and permeabilized for 30 min with PBS containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 mm NH4Cl, and 0.3% Triton X-100. The coverslips were then incubated with primary antibody or fluorophore-conjugated phalloidin for 1 h at room temperature, washed in PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted using the ProlongGold anti-fade mounting agent (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using Nikon Eclipse Ti with ×40 or ×100 objective using Micro-Manager open source software (32) and analyzed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, rsb.info.nih.gov).

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitor mixture tablets (Roche Applied Science). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad), and blocked for 1 h with 2% BSA in TBS-T (0.1 m Tris, pH 7.4, 135 mm NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, washed in TBS-T, and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies. Signal was detected using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology).

Flow Cytometry Assays of ASB2α Activity

Flow cytometry assays were described previously (7). Briefly, for the serial transfection, CHO cells were transfected with the indicated GFP-tagged constructs, and 24 h after transfection, cells were re-transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS. 48 h after the second transfection, cells were detached and washed in PBS, and GFP fluorescence intensity of dsRed-expressing cells was quantified using an LSRII instrument (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data analysis was carried out using FlowJo analysis software. Percent of protein remaining was defined as Fα/FαΔS × 100, where Fα is the GFP geometric mean fluorescence intensity of dsRed-ASB2α-expressing cells, and FαΔS is the GFP geometric mean fluorescence intensity of dsRed-ASB2αΔS-expressing cells.

Binding Assays

GST fusion proteins were produced in Escherichia coli BL21 Gold (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and purified on glutathione-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow medium (GE Healthcare) according to manufacturer's instructions. CHO cells were transiently transfected with GFP-ASB2α, harvested 24 h later, and lysed. Cell lysates were incubated overnight with GST, GST-FLNaABD, or GST-FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads, washed, and resuspended in SDS sample buffer. Bound proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GFP antibody.

Cell Spreading Assay

HeLa cells were plated on fibronectin-coated (5 μg/ml) coverslips, and 3 h after plating, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Cell areas were measured by manually rendering the cell contour in phase contrast.

RESULTS

ASB2α Targets CH1 of FLNa for Degradation

Using Western blotting, immunofluorescence, and flow cytometry assays, we previously showed that ASB2α expression triggers polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of filamins (5–7, 31). In keeping with our earlier studies (7), flow cytometric degradation assays show that the FLNa ABD is both necessary and sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation as the isolated ABD is efficiently degraded following ASB2α expression, although FLNa lacking the ABD is resistant to degradation (Fig. 1B). The ABDs of the three filamin isoforms show high sequence and structural similarity (30), and we previously demonstrated that the ABDs of FLNa, FLNb, and FLNc are efficiently targeted for degradation by ASB2α (7). Consistent with our flow cytometric data, Western blotting shows that co-expressing FLNaABD-GFP with ASB2α, but not the inactive mutant ASB2ΔS (which lacks the SOCS box and so is unable to engage the rest of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex), leads to loss of the FLNaABD (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, addition of the proteasome inhibitor, MG132, protects FLNaABD from ASB2α-mediated degradation. Thus, as we reported previously (7), ASB2α triggers proteasomal degradation of FLNa by targeting the ABD.

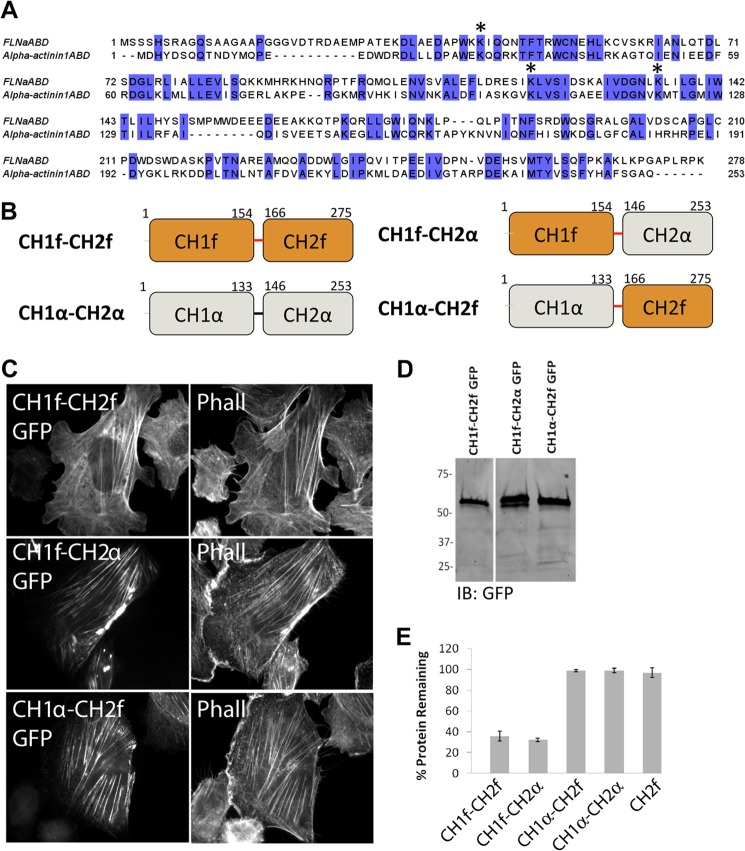

The ABD of filamin is composed of two calponin homology domains (CH1 and CH2) (30, 33, 34) separated by a linker region and contains three predicted actin-binding sites (ABS1, ABS2, and ABS3), two in CH1 and one in CH2 that together are thought to support binding to F-actin (Figs. 1A and 2A) (35). To narrow down the region within the FLNaABD that is targeted for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation by ASB2α, we generated GFP-tagged constructs corresponding to CH1 and CH2 (Fig. 2A). When expressed in cells, the CH1 of FLNa exhibited strong targeting to actin stress fibers, although CH2 failed to accumulate on stress fibers (Fig. 2B). Western blotting established that FLNaABD-GFP, FLNaCH1-GFP, and FLNaCH2-GFP were all of the expected sizes (Fig. 2C) indicating that the cytoplasmic localization of FLNaCH2-GFP is not due to a GFP degradation product (Fig. 2C). Our data therefore suggest that CH1 is sufficient for F-actin binding. This is consistent with published studies of CH domains in other ABD-containing proteins (35, 37–41). Furthermore, as was reported for the isolated α-actinin CH1 domain (35), the CH1 of FLNa exhibited aberrant clumping on stress fibers (Fig. 2B), suggesting that CH2 normally regulates a CH1-mediated interaction of FLNaABD with actin filaments.

FIGURE 2.

CH1 is the minimal fragment of FLNa sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation. A, primary amino acid sequence of FLNaABD. The ABD is composed of two calponin homology domains (CH1 and CH2) connected by a linker region. The predicted actin-binding sites (ABS1, ABS2, and ABS3) are indicated. Lysines are highlighted in blue, and the corresponding residue numbers are indicated above. B, CHO cells transfected with FLNaABD GFP, FLNaCH1 GFP, and FLNaCH2 GFP were fixed and stained for phalloidin (Phall). Scale bar, 10 μm. C, CHO cells transfected with FLNaABD GFP, FLNaCH1 GFP, and FLNaCH2 GFP were lysed and immunoblotted (IB) using anti-GFP antibody. D, CHO cells transiently expressing FLNaABD GFP, FLNaCH1 GFP, FLNaCH2 GFP, and FLNaΔABD GFP were transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS. 48 h after transfection, cells were detached and washed with PBS, and the GFP intensity of dsRed-expressing cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Bar chart depicts mean percentage of GFP-tagged protein remaining ± S.E. in dsRed-ASB2α-expressing cells normalized to levels in dsRed-ASB2αΔS-expressing cells (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Data are from at least seven independent experiments.

Having validated the expression and targeting of the GFP-tagged constructs, we tested the ability of the individual CH domains to be targeted for degradation by ASB2α using the flow cytometry-based assay described previously (7). Similar to FLNaABD-GFP, levels of FLNaCH1-GFP were substantially decreased in ASB2α-expressing cells (Fig. 2D). However, the level of FLNaCH2-GFP was unaffected, as was the level of FLNaΔABD (an FLNa mutant lacking the ABD), which we previously showed to be resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Figs. 1A and 2D). These data point to FLNaCH1 as the minimal region of FLNa sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation and suggest that FLNaCH1 is also sufficient for interaction with ASB2α.

Identification of Lysine Residues Required for ASB2α-mediated FLNaABD Degradation

We previously showed that ASB2α targets filamins for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (5, 6). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the ABD of filamin is necessary and sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation (7). Our finding that CH1 of FLNa is the minimal fragment targeted for degradation by ASB2α implies that CH1 harbors lysine residues targeted for ubiquitination by ASB2α. The ABD of FLNa contains 20 lysine residues (Fig. 2A), and 11 reside within CH1, whereas two are within the linker region (Fig. 2A). Thus, we sought to identify lysine residue(s) important for ASB2α-mediated degradation and subsequently to generate an ASB2α-resistant FLNaABD by mutagenesis of the target lysine residues.

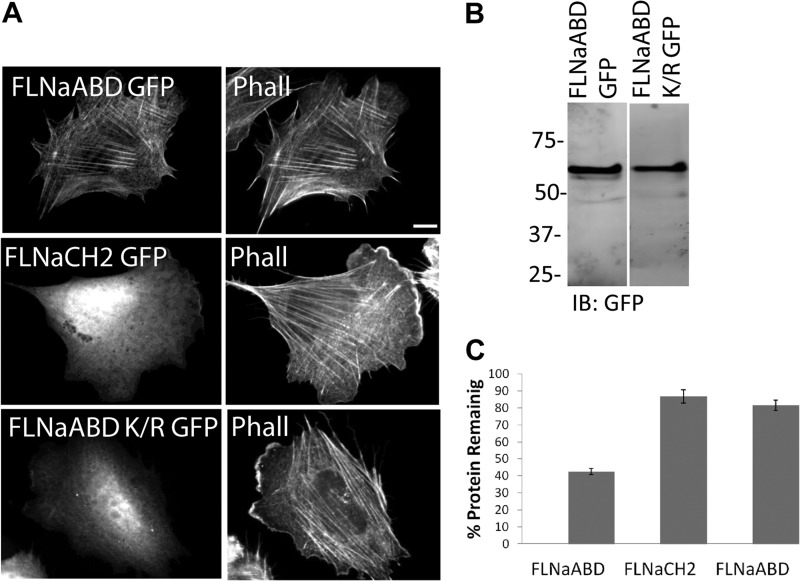

First, we performed a series of mutagenesis reactions to generate a mutant FLNaABD in which all 13 lysine residues within CH1 and the linker region (Fig. 2A) were substituted with charge-conserving arginine (FLNaABD Lys/Arg). When transiently expressed in cells, this mutant FLNaABD exhibited impaired association with F-actin at stress fibers and was mainly cytoplasmic (Fig. 3A). Western blotting revealed GFP-tagged protein of the expected size (Fig. 3B), excluding the possibility that GFP cleavage might explain the cytoplasmic localization of the FLNaABD Lys/Arg mutant. Although FLNaABD Lys/Arg mutant exhibits impaired association with F-actin at stress fibers (Fig. 3A), it is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Fig. 3C and Table 1). Thus, despite the presence of seven lysine residues in the CH2 and 20 lysines in the GFP tag, mutation of all 13 lysines in the CH1 plus linker region renders FLNaABD resistant to ASB2α-induced degradation indicating that CH1 lysine residues are required for ASB2α-mediated degradation.

FIGURE 3.

CH1 lysine to arginine substitution renders FLNaABD resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation. A, CHO cells transfected with FLNaABD GFP, FLNaCH2 GFP, and FLNaABD Lys/Arg GFP were fixed and stained for phalloidin (Phall). Scale bar, 10 μm. B, CHO cells transfected with FLNaABD GFP and FLNaABD Lys/Arg GFP were lysed and immunoblotted (IB) using anti-GFP antibody. C, CHO cells transiently expressing FLNaABD GFP, FLNaCH2 GFP, and FLNaABD Lys/Arg GFP were transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS. 48 h after transfection, cells were detached and washed with PBS, and the GFP intensity of dsRed-expressing cells was measured. Bar chart depicts mean percentage of GFP-tagged protein remaining ± S.E. in dsRed-ASB2α-expressing cells normalized to levels in dsRed-ASB2αΔS-expressing cells (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Data are from at least five independent experiments.

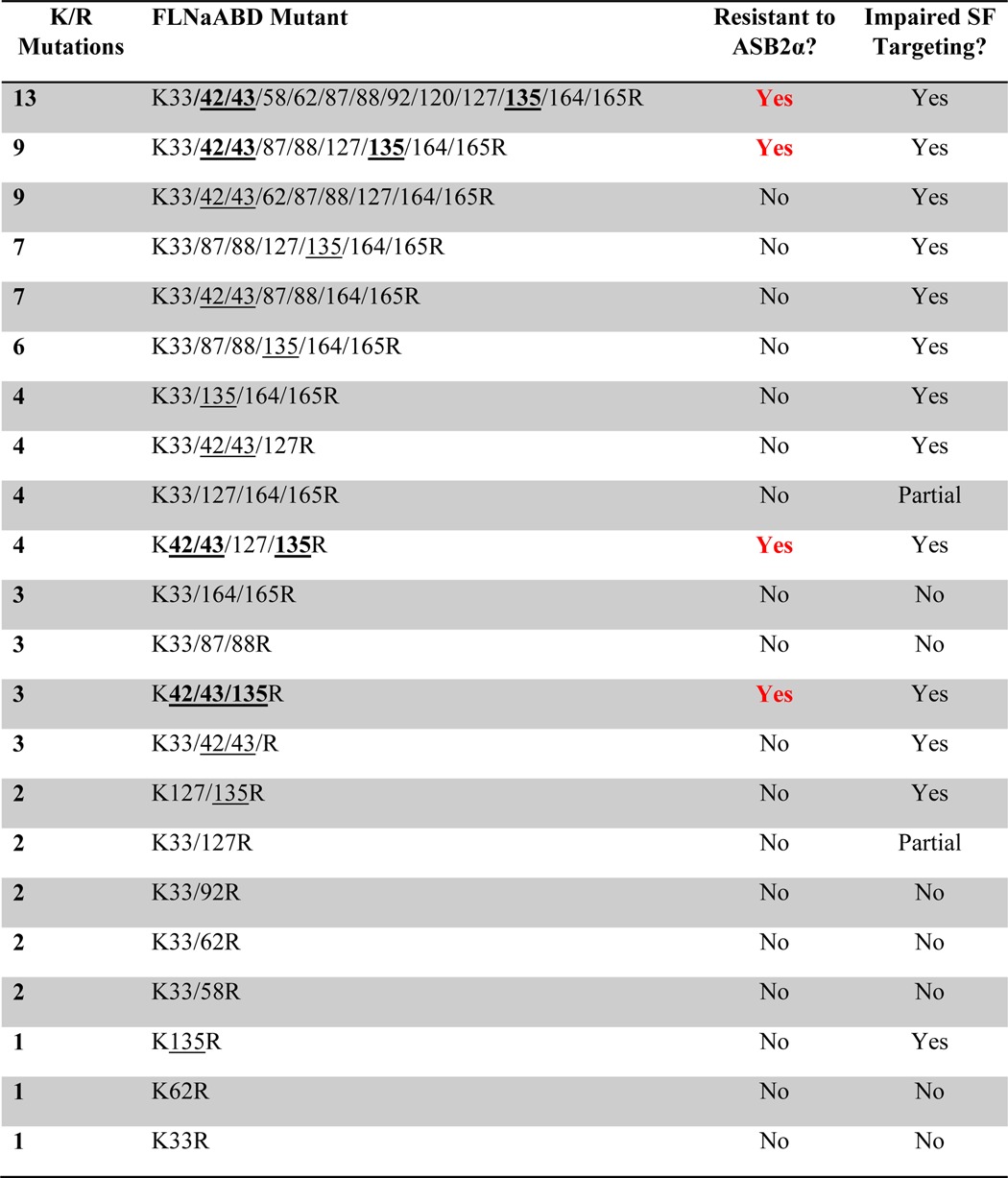

TABLE 1.

Select list of FLNaABD lysine to arginine mutants assessed for resistance to ASB2α-mediated degradation and stress fiber (SF) targeting

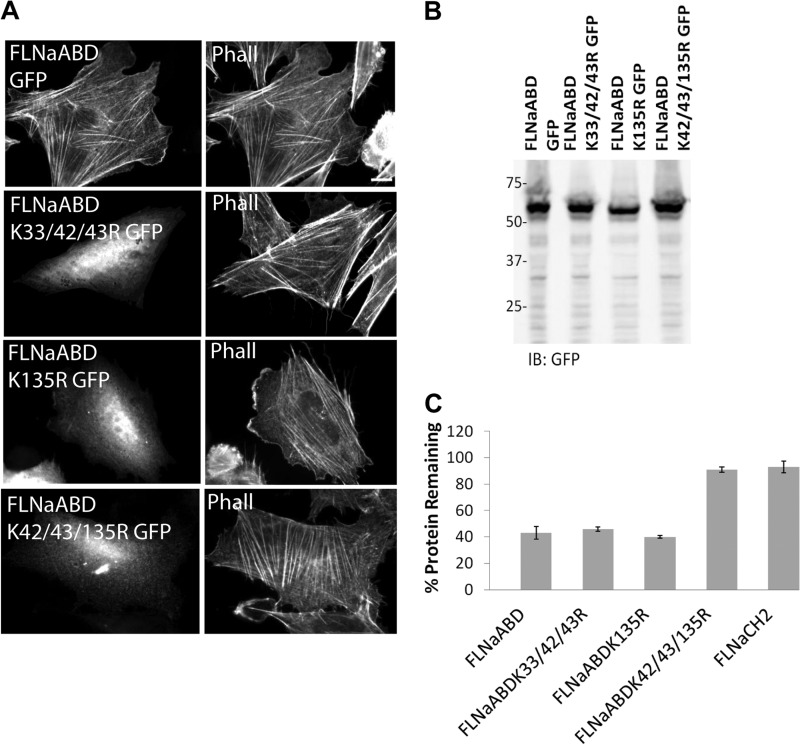

To determine which of the 13 lysine residues, or which combination of lysine residues, are required for FLNaABD degradation, various permutations of the FLNaABD Lys/Arg mutants were tested in the flow cytometric assay (Table 1). An in-depth analysis revealed that no single or double lysine to arginine substitution tested inhibited FLNaABD degradation (Table 1). However, all constructs containing a triple lysine to arginine substitution at positions 42, 43, and 135 were resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Table 1; Fig. 4C). Notably, all three of these lysines must be mutated to render FLNaABD resistant to degradation as the presence of either lysine 135 or of lysines 42 and 43 is sufficient to support ASB2α-triggered degradation (Fig. 4C) even in ABD mutants containing a total of nine other lysine to arginine mutations (Table 1). This suggests that lysines 42, 43, and 135 are likely to be acceptor sites for polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation and that polyubiquitination of any of these residues will support degradation.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of FLNaABD lysine residues important for ASB2α-mediated degradation. A, CHO cells transfected with FLNaABD GFP, FLNaABD K33R/K42R/K43R GFP (K33/42/43R GFP), FLNaABD K135R GFP, and FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R GFP (K42/43/135R GFP) were fixed and stained for phalloidin (Phall). Scale bar, 10 μm. B, CHO cells from A were lysed and immunoblotted (IB) using anti-GFP antibody. C, CHO cells transiently expressing FLNaABD GFP, FLNaABD K33R/K42R/K43R GFP, FLNaABD K135R GFP, FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R GFP, and FLNaCH2 were transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS, and 48 h later the mean ± S.E. percentage of GFP-tagged protein remaining in dsRed-ASB2α-expressing cells was assessed as in Fig. 1 (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Data are from at least three independent experiments.

ASB2α-mediated FLNaABD Degradation and F-actin Targeting Are Separable

In addition to characterizing their susceptibility to ASB2α-mediated degradation, we analyzed the lysine to arginine mutant FLNaABD constructs for their association with F-actin as assessed by stress fiber targeting. This revealed four lysine residues (at positions 42, 43, 127, and 135) whose mutation to arginine resulted in impaired stress fiber targeting (Table 1). Each of these lysine residues resides within the predicted actin-binding sites on CH1 (Fig. 2A), and it is likely that their mutation interferes with or disrupts F-actin binding. Thus, residues required for ASB2α-mediated degradation and for F-actin binding overlap, raising the question of whether the processes are linked.

As summarized in Table 1, all ASB2α-resistant mutants are defective in stress fiber targeting. However, failure to target to stress fibers is not sufficient to impart ASB2α resistance as several FLNaABD mutants, which exhibit cytoplasmic localization, are targeted for degradation by ASB2α (Table 1), illustrating that FLNaABD localization to stress fibers is dispensable for ASB2α-mediated degradation. As shown in Fig. 4A, FLNaABD mutant constructs K33R/K42R/K43R, K135R, and K42R/K43R/K135R all exhibit impaired targeting to stress fibers despite expression of GFP-tagged protein of the expected sizes as assessed by Western blotting (Fig. 4B). However, although FLNaABD K33R/K42R/K43R and FLNaABD K135R are targeted for degradation by ASB2α (Fig. 4C), FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Fig. 4C), confirming that any one of the three lysine residues (Lys-42, Lys-43, or Lys-135) is sufficient to sustain ASB2α-mediated degradation but showing that all three residues are required for F-actin association. Notably, lysine residues 42, 43, and 135 are in close proximity and are exposed at the surface and readily accessible from the outside as shown in the ribbon diagram of FLNaABD (Fig. 5A). Our identification of putative polyubiquitination sites within the actin-binding sites of FLNaCH1, which are likely to be buried when FLNa is bound to F-actin, suggests that FLNaABD bound to F-actin may be protected from degradation and that ubiquitination may occur only upon dissociation from F-actin.

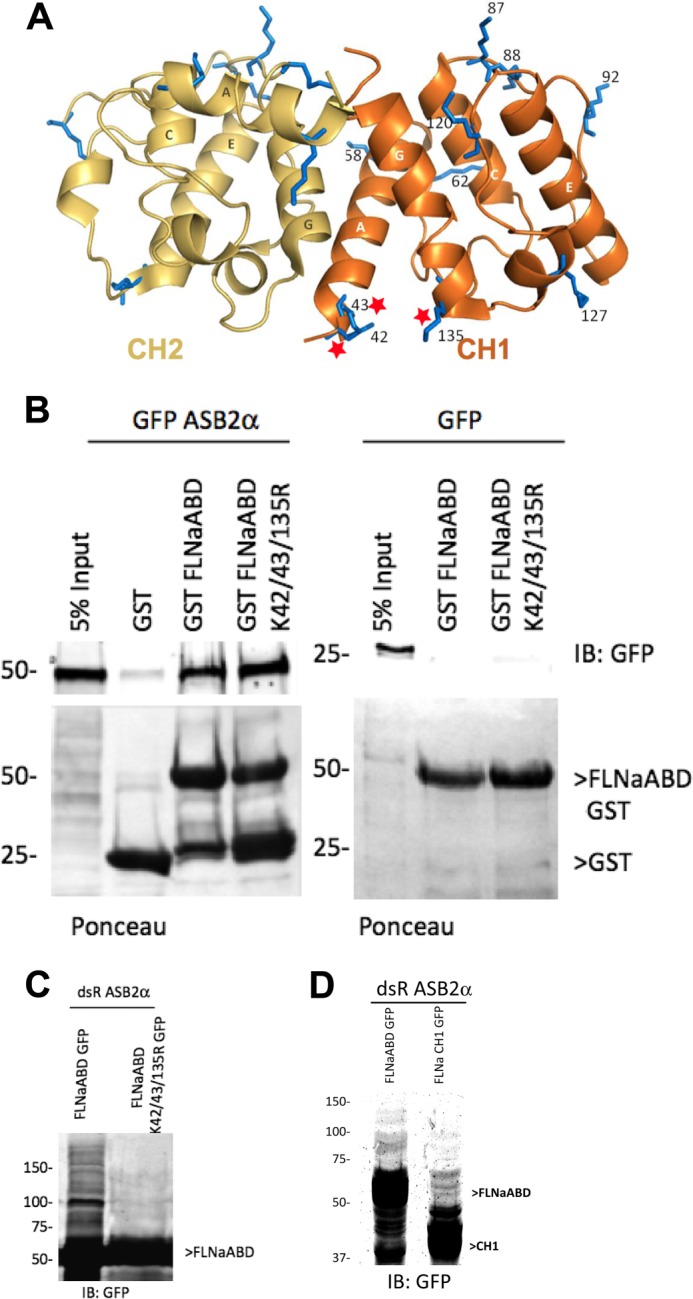

FIGURE 5.

FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R interacts with ASB2α. A, ribbon diagram of FLNaABD from Protein Data Bank code 2wfn (30). CH1 is depicted in orange and CH2 in yellow. Lysine residues are shown as sticks in blue and corresponding residue numbers in CH1 are indicated. The four dominant helices (A, C, E, and G) are labeled. Lysine residues 42, 43, and 135 are denoted by stars. B, CHO cells transfected with GFP ASB2α or GFP were lysed, and lysates were incubated with GST, GST FLNaABD, or GST FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R (K42/43/135R) coated onto glutathione-Sepharose beads. After incubation, beads were washed, and bound proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GFP antibody (upper panels). Bead coating with the GST proteins was assessed by Ponceau staining (lower panels). C, CHO cells were co-transfected with dsRed-ASB2α and FLNaABD GFP or FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R GFP in the presence of proteasome inhibitor MG132. 18 h after transfection, cells were dissolved in SDS sample buffer, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted using anti-GFP antibody. D, CHO cells were co-transfected with dsRed-ASB2α and FLNaABD GFP or FLNaCH1 GFP in the presence of proteasome inhibitor MG132. 18 h after transfection, cells were dissolved in SDS sample buffer, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted using anti-GFP antibody. IB, immunoblot.

FLNaABD Lys-42/43/135 Retains ASB2α Binding Activity

ASB2α-triggered proteasomal degradation of FLNa requires that the ASB2α E3 ubiquitin ligase complex associates with FLNa and catalyzes the addition of polyubiquitin chains onto lysine residues on FLNa. Our mutagenesis data establish that arginine substitution of lysine 42, 43, and 135 in FLNa ABD renders it resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation, suggesting that these CH1 lysine residues may either serve as ubiquitination sites and/or possibly be involved in mediating interaction with ASB2α as well as F-actin. To test whether mutation of these lysine residues disrupts the ability of FLNaABD to interact with ASB2α, we performed pulldown assays. Both GST-FLNaABD and GST-FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R bound to ASB2α, although only background binding was seen to the GST beads (Fig. 5B). Our results therefore indicate that lysine to arginine mutation on residues 42, 43, and 135 does not alter ASB2α interaction with FLNaABD, instead suggesting that these lysines serve as polyubiquitination sites during ASB2α-mediated proteasomal degradation. This effect is highly specific as we demonstrate that FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R is not targeted for degradation (Fig. 4C) even though all other lysine residues except 42, 43, and 135 are available and surface-exposed (Fig. 5A). To assess polyubiquitination, FLNaABD wild-type and FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R were co-expressed with ASB2α in the presence of MG132 (to prevent proteasomal degradation of the polyubiquitinated protein) and cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis. Indeed, a smear of higher molecular species, indicative of polyubiquitination, was seen for FLNaABD-GFP but not for FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R -GFP proteins (Fig. 5C). We further confirmed that, as expected, FLNaCH1-GFP also exhibited a smear of higher molecular weight species when co-expressed with ASB2α (Fig. 5D).

Full-length FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R Mutant Is Resistant to ASB2α-mediated Degradation

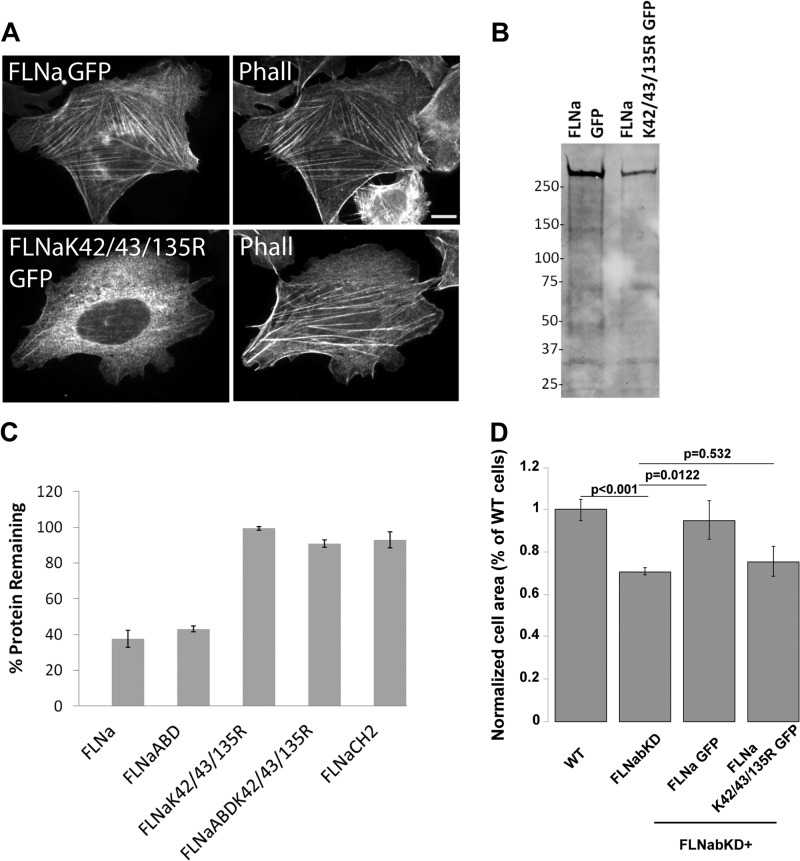

The preceding results demonstrate that FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation and is still capable of interacting with ASB2α, and the results suggest that lysine residues 42, 43, and 135 are required for ubiquitination and degradation of FLNa. Furthermore, our localization assays suggest that lysine residues 42, 43, and 135 are also important for F-actin association as mutagenesis of these lysine residues impairs FLNaABD targeting to stress fibers. We next asked whether mutagenesis of these specific lysine residues would render full-length FLNa resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation and affect FLNa targeting to stress fibers. As shown in Fig. 6A, full-length FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R also exhibits impaired targeting to stress fibers, and unlike FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R (Fig. 4A), some weak targeting is observed. We suggest that this is likely to be due to dimerization of the mutant FLNa with endogenous CHO cell FLNa. Analysis of lysates from transfected cells revealed bands of the expected size for FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R (Fig. 6B). Importantly, similar to FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R, full-length FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Fig. 6C). These results validate our earlier findings and suggest that ASB2α targeted degradation of full-length FLNa can be mediated by three different lysine residues.

FIGURE 6.

Full-length FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation and impaired in targeting to stress fibers. A, CHO cells transfected with full-length FLNa GFP and FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R GFP were fixed and stained for phalloidin (Phall). Scale bar, 10 μm. B, CHO cells transfected with full-length FLNa GFP and FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R GFP (K42/43/135R GFP) were lysed and immunoblotted using anti-GFP antibody. C, CHO cells transiently expressing full-length FLNa GFP, FLNaABD GFP, full-length FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R GFP, FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R GFP, and FLNaCH2 GFP were transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS, and FLNa degradation was assessed as described in Fig. 1 (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Bar chart depicts mean percentage of GFP-tagged protein remaining ± S.E. Data are from at least six independent experiments. D, HT1080 wild-type (WT) and FLNa and FLNb double knockdown cells (FLNabKD) or FLNabKD cells transiently expressing either wild-type FLNa GFP or FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R GFP were plated on fibronectin-coated coverslips. 3 h after plating, cells were fixed, and areas were measured by manually rendering the cell contour in phase contrast and normalized to the size of untransfected WT cells. Bar chart depicts mean relative cell area ± S.E. for each condition from three independent experiments (>20 cells per condition). p values were calculated using the t test.

FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R Does Not Rescue Impaired Spreading of Filamin Knockdown Cells

We previously showed that ASB2α expression induces proteasome-mediated degradation of all three filamin isoforms and impairs cell spreading (5, 6). As cell knockdown for both FLNa and FLNb is also impaired in spreading (5, 6), it was proposed that ASB2α regulates hematopoietic cell spreading by targeting filamins for degradation (5, 26, 31). To test whether filamin degradation is the only mechanism by which ASB2α impacts cell spreading, we first sought to generate ASB2α-resistant filamin constructs for use in reconstitution studies. As described above, we have now identified an ASB2α-resistant full-length FLNa mutant (FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R). However, this mutant is defective in stress fiber targeting suggesting that its F-actin binding activity is impaired. To determine whether the mutant FLNa is functional, we first tested its ability to rescue spreading of HT1080 double FLNa and FLNb knockdown (FLNabKD) cells. We previously showed that knockdown of FLNa and FLNb impairs cell spreading and that expressing an shRNA-resistant full-length FLNa rescues the spreading phenotype (Fig. 6D) (6). However, whereas re-expression of knockdown-resistant full-length FLNa rescues the spreading defect of FLNabKD cells, the FLNa K42R/K43R/K135R mutant does not (Fig. 6D), suggesting that F-actin binding is important for filamin's role in cell spreading.

FLNa Chimera Containing CH1 of α-Actinin1 Is Resistant to ASB2α-mediated Degradation

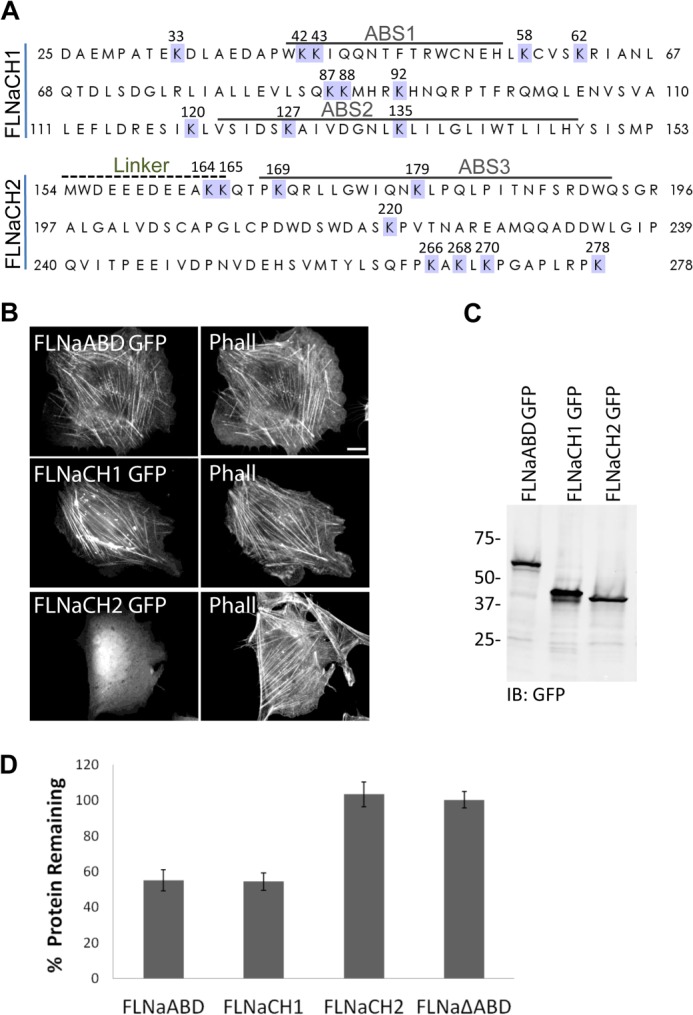

We have identified putative ubiquitination sites on FLNa and generated an ASB2α-resistant FLNa mutant. However, as this mutant is also defective in stress fiber localization, presumably due to impaired F-actin binding, the resulting protein is nonfunctional. We therefore sought an alternative approach to generate ASB2α-resistant filamin with a normal subcellular localization. We previously demonstrated that ASB2α specifically triggers degradation of the ABD of filamins but not of α-actinin1 (7), despite their related structure and similar sequence (Fig. 7A) (30). Thus, we sought to generate another ASB2α-resistant filamin by swapping CH1 of FLNaABD with that of α-actinin1. Two ABD-GFP chimeras were generated as follows: one contains CH1 of FLNa followed by linker region of FLNa plus CH2 of α-actinin1 (CH1f-CH2α), and the other contains CH1 of α-actinin1 also followed by linker region of FLNa plus CH2 of FLNa (CH1α-CH2f) (Fig. 7B). When expressed in CHO cells, both chimeras produce GFP-tagged proteins of the expected sizes as analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 7D). When their subcellular localization was analyzed, both chimeras show strong targeting to F-actin at stress fibers (Fig. 7B) illustrating that they are functional. These results are consistent with previous studies that showed that similar filamin and α-actinin1 CH domain chimeras interact with F-actin in vitro and in vivo (35).

FIGURE 7.

ASB2α targets ABD chimera CH1f-CH2α, but not CH1α-CH2, for degradation. A, sequence alignment of human FLNaABD and α-actinin1ABD. The sequences are aligned with ClustalW2 and colored by sequence identity. Conserved lysine residues within CH1 are denoted by stars. B, schematic representation of FLNaABD (CH1f-CH2f), α-actinin1ABD (CH1α-CH2α), CH1α-CH2f (aa 1–133 of α-actinin1 plus aa 166–275 of FLNa), and CH1f-CH2α (aa 1–154 of FLNa plus aa 146–253 of α-actinin1) chimeras both comprising the linker region of FLNa (aa 155–165). C, CHO cells transfected with CH1f-CH2f GFP, CH1f-CH2α GFP, and CH1α-CH2f GFP were fixed and stained for phalloidin (Phall). D, cells from C were lysed and immunoblotted (IB) using anti-GFP antibody. E, CHO cells transiently expressing CH1f-CH2f (FLNaABD) GFP, CH1f-CH2α GFP and CH1α-CH2f GFP, CH1α-CH2α (α-actinin1ABD) GFP, and CH2 GFP were transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS, and protein degradation was assessed as in Fig. 1. Bar chart depicts mean percentage of GFP-tagged protein remaining ± S.E. in dsRed-ASB2α-expressing cells normalized to levels in dsRed-ASB2αΔS expressing cells (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Data are from at least three independent experiments.

We next tested ASBS2 α-mediated degradation of the two chimeras. We employed the previously described flow cytometry-based degradation assay (7) to show that CH1f-CH2α but not CH1α-CH2f is targeted for degradation by ASB2α (Fig. 7E). These results extend our earlier findings and confirm that CH1 is the minimal FLNa fragment sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation and that, despite their structural similarity, ASB2α-mediated degradation is specific for CH1 of FLNa over CH1 of α-actinin.

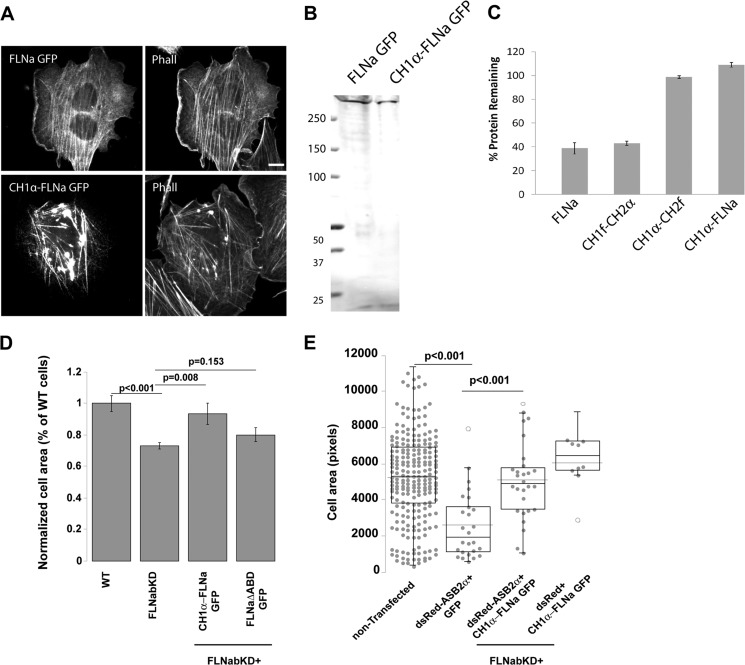

As the chimera comprising CH1α-CH2f is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Fig. 7E), we sought to generate a full-length FLNa resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation and capable of binding F-actin by swapping the CH1 of full-length FLNa with that of α-actinin1 (CH1α-FLNa). This construct expressed at the expected size as illustrated by Western blotting (Fig. 8B). Importantly, although the chimera exhibited some aberrant clumping, it associated with F-actin at stress fibers (Fig. 8A) and is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 8D, the ASB2α-resistant full-length FLNa chimera (CH1α-FLNa) rescues the spreading phenotype of FLNabKD HT1080 cells, suggesting that it is functional, whereas FLNaΔABD does not rescue the spreading defect (Fig. 8D). We have therefore generated an ASB2α-resistant FLNa that targets to stress fibers and supports cell spreading.

FIGURE 8.

Full-length FLNa chimera containing CH1 of α-actinin1 is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation and rescues spreading in filamin-deficient cells. A, CHO cells transfected with full-length FLNa GFP and CH1α-FLNa GFP were fixed and stained for phalloidin (Phall). Scale bar, 10 μm. B, cells from A were lysed and blotted using anti-GFP antibody. C, CHO cells transiently expressing full-length FLNa GFP, CH1f-CH2α GFP, CH1α-CH2f, and CH1α-FLNa GFP were transfected with either dsRed-ASB2α or dsRed-ASB2αΔS, and degradation of the GFP protein in ASB2α-expressing cells was assessed 48 h later as in Fig. 1 (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Data are from at least four independent experiments. D, HT1080 WT, FLNabKD, or FLNabKD cells transiently transfected with CH1α-FLNa GFP or FLNaΔABD GFP were plated on fibronectin-coated coverslips. 3 h after plating, cells were fixed, and areas were measured by manually rendering the cell contour in phase contrast. Areas were normalized to the mean WT area and presented as mean.± S.E. from three independent experiments (>16 cells per condition). p values were calculated using the t test. E, HeLa cells were co-transfected with dsRed-ASB2α and GFP (dsRed-ASB2α + GFP), dsRed-ASB2α and CH1α-FLNa GFP (dsRed-ASB2α + CH1α-FLNa GFP), or dsRed and CH1α-FLNa GFP (dsRed + CH1α-FLNa GFP). 48 h after transfection, cells were detached and re-plated on fibronectin-coated coverslips. 3 h after plating, cells were fixed, and the areas dsRed and GFP double-positive cells were measured and compared with the nontransfected cells. Pixel = 0.416 μm2. Dot plot shows the overall population distribution from four independent experiments; dotted line shows the mean area, and the box and whiskers plots show quartiles. p values were calculated using the t test.

CH1α-FLNa Chimera Rescues Impaired Spreading Induced by ASB2α

To determine whether the spreading defect associated with ASB2α expression can be rescued by expression of an ASB2α-resistant FLNa, we co-expressed dsRed-tagged ASB2α with GFP or CH1α-FLNa GFP and assessed cell area. As reported previously (5, 6), we find that ASB2α expression impairs cell spreading when compared with nontransfected cells on the same coverslip (Fig. 8E). Interestingly, CH1α-FLNa GFP, but not GFP, rescues impaired spreading induced by ASB2α (Fig. 8E). We also co-expressed dsRed and CH1α-FLNa GFP and show that CH1α-FLNa GFP does not affect cell size when co-expressed with dsRed (Fig. 8E) further supporting that the CH1α-FLNa chimera rescues impaired spreading induced by ASB2α. In summary, this chimera targets to stress fibers (Fig. 8A), is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (Fig. 8C), and rescues spreading phenotype of FLNabKD cells (Fig. 8D) as well as ASB2α-expressing cells (Fig. 8E).

DISCUSSION

ASB2α is thought to regulate hematopoietic cell differentiation by modulating cell spreading, actin remodeling, and cell adhesion (5, 31), and the importance of ASB2α is supported by a recent knock-out mouse study showing that ASB2α is a critical regulator of spreading and migration in immature dendritic cells (26). We have established that ASB2α targets filamins for proteasomal degradation (5, 6, 31), have shown that the N-terminal region of ASB2α along with the first 10 ankyrin repeats supports ASB2α binding to filamins (31), and have revealed that the ABD of filamin mediates interaction with ASB2α and is sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation (7). Here, we extend those studies to show that ASB2α targets CH1 of FLNa for proteasomal degradation, and we identify a cluster of three lysine residues on the surface of CH1 that is required for ASB2α-mediated proteasomal degradation of FLNa. We find that these lysines are also involved in FLNa binding to F-actin and that this is required to rescue spreading defects in filamin knockdown cells. We build on this information to show that an ASB2α-resistant chimeric FLNa protein, in which the FLNa CH1 is replaced by the α-actinin CH1, retains localization to actin stress fibers and fully restores spreading in ASB2α-expressing cells, demonstrating that the spreading defect induced by ASB2α is due to the acute loss of filamins.

Our finding that CH1 of FLNa is the minimal fragment targeted for degradation by ASB2α implies that CH1 harbors both the ASB2α-binding and ubiquitination sites. We previously showed that ASB2α targets filamins for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (5–7) and narrowed potential ubiquitination sites from 156 lysines within full-length FLNa to 20 within the ABD (7) and here to 11 within CH1. Thus, we sought to generate an ASB2α-resistant FLNaABD by mutagenesis of the lysine residues within CH1 and used an in-depth flow cytometry analysis to identify candidate sites of ubiquitination. We find that mutation of all CH1 lysine residues to arginine within the context of FLNaABD renders FLNaABD resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation. Interestingly, mutation of only three lysine residues (Lys-42, Lys-43, and Lys-135) is sufficient to make FLNaABD, or full-length FLNa, resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation even though all other lysine residues remain available for ubiquitination.

The specificity of ASB2α is further illustrated by our observation that despite the structural similarity of the FLNa CH1 and CH2 domains (Protein Data Bank code 3HOP chain A: root mean square deviation of 1.35 Å over 75 carbon α atoms and 23% sequence identity), only FLNa CH1 is targeted for ASB2α-mediated degradation. Likewise, the FLNa CH1 shares even greater structural and sequence similarity for the CH1 domain of α-actinin1 (Protein Data Bank code 2EYI residues 26–140: root mean square deviation of 0.97 over 104 carbon α atoms and 45% sequence identity), and yet α-actinin is not targeted by ASB2α. The structural basis for ASB2α specificity is not yet known, but presumably requires both an ASB2α-binding site and an appropriately positioned acceptor lysine. Notably, FLNa lysine residues 42, 43, and 135 are in close proximity, exposed at the surface, and readily accessible from the outside. Furthermore, our data suggest that the presence of any one of these three lysine residues is sufficient to sustain ASB2α-mediated degradation. Importantly, we show that FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R is capable of interacting with ASB2α suggesting that mutation of these lysine residues has not interfered with ASB2α binding and that lysine residues 42, 43, and 135 in fact serve as polyubiquitination acceptor sites. This conclusion is supported by Western blotting showing that in the presence of proteasome inhibitors wild-type FLNaCH1 and FLNaABD, but not the FLNaABD K42R/K43R/K135R triple mutant, exhibit higher molecular weight smears consistent with polyubiquitination.

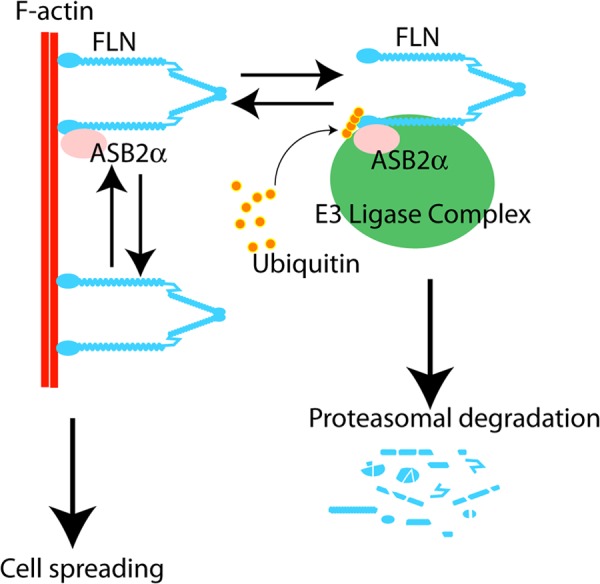

The major known function of FLNa CH domains is as the primary actin-binding site. We therefore tested whether the lysine to arginine mutations impacted the ability of the ABD to localize to actin stress fibers. Mutating all CH1 lysines very strongly impaired association with F-actin suggesting that lysine residues within CH1 are important for interaction with F-actin. Specifically, we identified lysine residues 42, 43, and 135 as important for association with F-actin and also found that mutation of Lys-127 partially impaired ABD localization (Table 1). Consistent with this, all four of these lysine residues reside within the two predicted actin-binding sites in CH1 (30, 33, 34). That CH1 residues required for degradation are also needed for stress fiber localization suggests that filamin bound to F-actin may be resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation as lysine residues 42, 43, 135 may be unavailable for ubiquitination. We speculate that FLN must dissociate from F-actin in order for the target lysine residues to be exposed for ubiquitination and subsequently targeted for proteasomal degradation (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Schematic summary of proposed model. The ABD of FLN interacts with F-actin and ASB2α. ASB2α targets lysine residues within FLN CH1 domain, and mutations in CH1 render FLN ASB2α-resistant. FLN bound to F-actin is protected from ASB2α-mediated degradation and regulates cell spreading. Upon dissociation from F-actin, lysine residues within the CH1 are exposed and available for polyubiquitination leading to subsequent proteasomal degradation.

Our data on FLNa ABD localization are consistent with studies of other ABD-containing proteins (35, 37–41). We find that FLNa CH1 but not CH2 displays considerable association with F-actin at stress fibers. Furthermore, expression of CH1 alone also results in aberrant clumping in cells suggesting that the CH2 domain is essential for proper interaction of FLNaABD with actin filaments. Studies on CH domains of α-actinin1 suggest that the CH2 regulates interaction and dynamics of the ABD with actin filaments and that in the absence of CH2, ABS1 within CH1 may become more accessible and contribute to increased filament association (35).

We previously showed that ASB2α specifically targets the ABD of FLNa, FLNb, and FLNc for degradation and that the ABD of α-actinin1 is resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation (7). Therefore, having identified CH1 as the minimal fragment of FLNa sufficient for ASB2α-mediated degradation, we complemented our mutagenesis studies with a chimeric protein approach and generated an ASB2α-resistant FLNa by swapping CH1 of FLNa with that of α-actinin1. Consistent with previous studies, both the chimeric ABD and chimeric FLNa targeted to stress fibers and exhibited clumping in cells, presumably due to increased F-actin binding (35). Nonetheless, the chimeras were resistant to ASB2α-mediated degradation, and the chimeric FLNa is functional and rescues spreading of filamin knockdown cells and ASB2α-expressing cells.

The exact mechanism by which ASB2α-mediated filamin degradation affects differentiation remains to be determined. Until recently, retinoic acid was the only pathway known to trigger ASB2α expression, and filamins were the only known ASB2α substrate. However, more recent studies found that ASB2α expression can be induced by Notch signaling (27) and identified mixed lineage leukemia (29), Jak2 (27), and Jak3 (28) as potential substrates. However, Jak2 and Jak3 are not regulated by ASB2α during hematopoietic differentiation (42). Our data establish that filamin degradation accounts for the spreading defects seen following ASB2α expression, and we postulate that ASB2α contributes to hematopoietic differentiation, through filamin degradation.

In keeping with this, filamins have been implicated in differentiation of various cell types (5, 15, 16, 43–45) and are down-regulated during differentiation of hematopoietic cells (5), muscle cells (15), and chondrocytes (16, 45) as well as maturation of dendritic cells (26). One possible mechanism involves the role of filamins in cytoskeletal re-organization and cell shape, which are integral aspects of differentiation (46, 47). ASB2α may therefore control differentiation by modulating cell spreading and actin remodeling through targeting of filamins for degradation.

Filamins may also control differentiation through transcriptional regulation (16, 45). Specifically, filamins have been shown to regulate activity of the PEBP2/CBF transcription factors (16, 48), which play fundamental roles in organ development (49) and differentiation of various cell types, including hematopoietic cells (50–52), muscles (36), as well as chondrocytes (16, 45). Notably, a recent study demonstrated a role for FLNa in chondrocyte differentiation and showed that FLNa knockdown significantly increases chondrocyte differentiation (16). Consistently, we find that ASB2α-mediated filamin degradation correlates with differentiation in hematopoietic cells (5).

In summary, proteasomal degradation of filamins provides a mechanism to explain ASB2α-mediated effects on hematopoietic cell differentiation. Our studies provide detailed insight into ASB2α-mediated filamin degradation, identify lysine residues required for targeted degradation, and establish that loss of filamin explains the effect of ASB2α on cell spreading. The ASB2α-resistant filamins described here will provide essential tools for future functional studies to elucidate if, and how, filamins mediate ASB2α's effects on cell differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pierre G. Lutz (Institut de Pharmacologie et de Biologie Structurale and Université de Toulouse, Toulouse, France) for originally providing ASB2α expression constructs and Titus Boggon (Yale University) for help with structural analysis.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM-068600 (to D. A. C.). This work was also supported by an award from the American Heart Association (to Z. R.).

- ASB2

- ankyrin repeat-containing protein with a suppressor of cytokine signaling box-2

- FLN

- filamin

- ABD

- actin-binding domain

- CH1

- calponin homology domain 1

- Jak

- Janus kinase

- aa

- amino acid

- SOCS

- suppressor of cytokine signaling.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guibal F. C., Moog-Lutz C., Smolewski P., Di Gioia Y., Darzynkiewicz Z., Lutz P. G., Cayre Y. E. (2002) ASB-2 inhibits growth and promotes commitment in myeloid leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 218–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kohroki J., Fujita S., Itoh N., Yamada Y., Imai H., Yumoto N., Nakanishi T., Tanaka K. (2001) ATRA-regulated Asb-2 gene induced in differentiation of HL-60 leukemia cells. FEBS Lett. 505, 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heuzé M. L., Guibal F. C., Banks C. A., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C., Cayre Y. E., Benecke A., Lutz P. G. (2005) ASB2 is an Elongin BC-interacting protein that can assemble with Cullin 5 and Rbx1 to reconstitute an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5468–5474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kohroki J., Nishiyama T., Nakamura T., Masuho Y. (2005) ASB proteins interact with Cullin5 and Rbx2 to form E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes. FEBS Lett. 579, 6796–6802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heuzé M. L., Lamsoul I., Baldassarre M., Lad Y., Lévêque S., Razinia Z., Moog-Lutz C., Calderwood D. A., Lutz P. G. (2008) ASB2 targets filamins A and B to proteasomal degradation. Blood 112, 5130–5140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baldassarre M., Razinia Z., Burande C. F., Lamsoul I., Lutz P. G., Calderwood D. A. (2009) Filamins regulate cell spreading and initiation of cell migration. PLoS One 4, e7830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Razinia Z., Baldassarre M., Bouaouina M., Lamsoul I., Lutz P. G., Calderwood D. A. (2011) The E3 ubiquitin ligase specificity subunit ASB2α targets filamins for proteasomal degradation by interacting with the filamin actin-binding domain. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2631–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Razinia Z., Mäkelä T., Ylänne J., Calderwood D. A. (2012) Filamins in mechanosensing and signaling. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 227–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stossel T. P., Condeelis J., Cooley L., Hartwig J. H., Noegel A., Schleicher M., Shapiro S. S. (2001) Filamins as integrators of cell mechanics and signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feng Y., Walsh C. A. (2004) The many faces of filamin: a versatile molecular scaffold for cell motility and signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1034–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou A. X., Hartwig J. H., Akyürek L. M. (2010) Filamins in cell signaling, transcription and organ development. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou X., Borén J., Akyürek L. M. (2007) Filamins in cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 17, 222–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gorlin J. B., Yamin R., Egan S., Stewart M., Stossel T. P., Kwiatkowski D. J., Hartwig J. H. (1990) Human endothelial actin-binding protein (ABP-280, nonmuscle filamin): a molecular leaf spring. J. Cell Biol. 111, 1089–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pudas R., Kiema T. R., Butler P. J., Stewart M., Ylänne J. (2005) Structural basis for vertebrate filamin dimerization. Structure 13, 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bello N. F., Lamsoul I., Heuzé M. L., Métais A., Moreaux G., Calderwood D. A., Duprez D., Moog-Lutz C., Lutz P. G. (2009) The E3 ubiquitin ligase specificity subunit ASB2β is a novel regulator of muscle differentiation that targets filamin B to proteasomal degradation. Cell Death Differ. 16, 921–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson K., Zhu S., Tremblay M. S., Payette J. N., Wang J., Bouchez L. C., Meeusen S., Althage A., Cho C. Y., Wu X., Schultz P. G. (2012) A stem cell-based approach to cartilage repair. Science 336, 717–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fox J. W., Lamperti E. D., Ekşioğlu Y. Z., Hong S. E., Feng Y., Graham D. A., Scheffer I. E., Dobyns W. B., Hirsch B. A., Radtke R. A., Berkovic S. F., Huttenlocher P. R., Walsh C. A. (1998) Mutations in filamin 1 prevent migration of cerebral cortical neurons in human periventricular heterotopia. Neuron 21, 1315–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Robertson S. P. (2005) Filamin A: phenotypic diversity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robertson S. P., Twigg S. R., Sutherland-Smith A. J., Biancalana V., Gorlin R. J., Horn D., Kenwrick S. J., Kim C. A., Morava E., Newbury-Ecob R., Orstavik K. H., Quarrell O. W., Schwartz C. E., Shears D. J., Suri M., Kendrick-Jones J., Wilkie A. O. (2003) Localized mutations in the gene encoding the cytoskeletal protein filamin A cause diverse malformations in humans. Nat. Genet. 33, 487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sarkisian M. R., Bartley C. M., Rakic P. (2008) Trouble making the first move: interpreting arrested neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci. 31, 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krakow D., Robertson S. P., King L. M., Morgan T., Sebald E. T., Bertolotto C., Wachsmann-Hogiu S., Acuna D., Shapiro S. S., Takafuta T., Aftimos S., Kim C. A., Firth H., Steiner C. E., Cormier-Daire V., Superti-Furga A., Bonafe L., Graham J. M., Jr., Grix A., Bacino C. A., Allanson J., Bialer M. G., Lachman R. S., Rimoin D. L., Cohn D. H. (2004) Mutations in the gene encoding filamin B disrupt vertebral segmentation, joint formation, and skeletogenesis. Nat. Genet. 36, 405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bicknell L. S., Morgan T., Bonafé L., Wessels M. W., Bialer M. G., Willems P. J., Cohn D. H., Krakow D., Robertson S. P. (2005) Mutations in FLNB cause boomerang dysplasia. J. Med. Genet. 42, e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kley R. A., Hellenbroich Y., van der Ven P. F., Fürst D. O., Huebner A., Bruchertseifer V., Peters S. A., Heyer C. M., Kirschner J., Schröder R., Fischer D., Müller K., Tolksdorf K., Eger K., Germing A., Brodherr T., Reum C., Walter M. C., Lochmüller H., Ketelsen U. P., Vorgerd M. (2007) Clinical and morphological phenotype of the filamin myopathy: a study of 31 German patients. Brain 130, 3250–3264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vorgerd M., van der Ven P. F., Bruchertseifer V., Löwe T., Kley R. A., Schröder R., Lochmüller H., Himmel M., Koehler K., Fürst D. O., Huebner A. (2005) A mutation in the dimerization domain of filamin c causes a novel type of autosomal dominant myofibrillar myopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77, 297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duff R. M., Tay V., Hackman P., Ravenscroft G., McLean C., Kennedy P., Steinbach A., Schöffler W., van der Ven P. F., Fürst D. O., Song J., Djinović-Carugo K., Penttilä S., Raheem O., Reardon K., Malandrini A., Gambelli S., Villanova M., Nowak K. J., Williams D. R., Landers J. E., Brown R. H., Jr., Udd B., Laing N. G. (2011) Mutations in the N-terminal actin-binding domain of filamin C cause a distal myopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 729–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lamsoul I., Metais A., Gouot E., Heuze M. L., Lennon-Dumenil A. M., Moog-Lutz C., Lutz P. G. (2013) ASB2α regulates migration of immature dendritic cells. Blood 122, 533–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nie L., Zhao Y., Wu W., Yang Y. Z., Wang H. C., Sun X. H. (2011) Notch-induced Asb2 expression promotes protein ubiquitination by forming non-canonical E3 ligase complexes. Cell Res. 21, 754–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu W., Sun X. H. (2011) A mechanism underlying NOTCH-induced and ubiquitin-mediated JAK3 degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41153–41162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang J., Muntean A. G., Hess J. L. (2012) ECSASB2 mediates MLL degradation during hematopoietic differentiation. Blood 119, 1151–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ruskamo S., Ylänne J. (2009) Structure of the human filamin A actin-binding domain. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1217–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lamsoul I., Burande C. F., Razinia Z., Houles T. C., Menoret D., Baldassarre M., Erard M., Moog-Lutz C., Calderwood D. A., Lutz P. G. (2011) Functional and structural insights into ASB2α, a novel regulator of integrin-dependent adhesion of hematopoietic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 30571–30581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Edelstein A., Amodaj N., Hoover K., Vale R., Stuurman N. (2010) Computer control of microscopes using μManager. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 14, Unit 14.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sawyer G. M., Clark A. R., Robertson S. P., Sutherland-Smith A. J. (2009) Disease-associated substitutions in the filamin B actin binding domain confer enhanced actin binding affinity in the absence of major structural disturbance: Insights from the crystal structures of filamin B actin binding domains. J. Mol. Biol. 390, 1030–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clark A. R., Sawyer G. M., Robertson S. P., Sutherland-Smith A. J. (2009) Skeletal dysplasias due to filamin A mutations result from a gain-of-function mechanism distinct from allelic neurological disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 4791–4800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gimona M., Djinovic-Carugo K., Kranewitter W. J., Winder S. J. (2002) Functional plasticity of CH domains. FEBS Lett. 513, 98–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chiba N., Watanabe T., Nomura S., Tanaka Y., Minowa M., Niki M., Kanamaru R., Satake M. (1997) Differentiation-dependent expression and distinct subcellular localization of the protooncogene product, PEBP2β/CBFβ, in muscle development. Oncogene 14, 2543–2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Way M., Pope B., Weeds A. G. (1992) Evidence for functional homology in the F-actin binding domains of gelsolin and α-actinin: implications for the requirements of severing and capping. J. Cell Biol. 119, 835–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McGough A., Way M., DeRosier D. (1994) Determination of the α-actinin-binding site on actin filaments by cryoelectron microscopy and image analysis. J. Cell Biol. 126, 433–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakamura A., Hanyuda Y., Okagaki T., Takagi T., Kohama K. (2005) A calmodulin-dependent protein kinase from lower eukaryote Physarum polycephalum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 328, 838–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Winder S. J., Hemmings L., Maciver S. K., Bolton S. J., Tinsley J. M., Davies K. E., Critchley D. R., Kendrick-Jones J. (1995) Utrophin actin binding domain: analysis of actin binding and cellular targeting. J. Cell Sci. 108, 63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Djinovic Carugo K., Bañuelos S., Saraste M. (1997) Crystal structure of a calponin homology domain. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4, 175–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lamsoul I., Erard M., van der Ven P. F., Lutz P. G. (2012) Filamins but not Janus kinases are substrates of the ASB2α cullin-ring E3 ubiquitin ligase in hematopoietic cells. PLoS One 7, e43798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lu J., Lian G., Lenkinski R., De Grand A., Vaid R. R., Bryce T., Stasenko M., Boskey A., Walsh C., Sheen V. (2007) Filamin B mutations cause chondrocyte defects in skeletal development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 1661–1675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van der Flier A., Kuikman I., Kramer D., Geerts D., Kreft M., Takafuta T., Shapiro S. S., Sonnenberg A. (2002) Different splice variants of filamin-B affect myogenesis, subcellular distribution, and determine binding to integrin (β) subunits. J. Cell Biol. 156, 361–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zheng L., Baek H. J., Karsenty G., Justice M. J. (2007) Filamin B represses chondrocyte hypertrophy in a Runx2/Smad3-dependent manner. J. Cell Biol. 178, 121–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McBeath R., Pirone D. M., Nelson C. M., Bhadriraju K., Chen C. S. (2004) Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev. Cell 6, 483–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Connelly J. T., García A. J., Levenston M. E. (2008) Interactions between integrin ligand density and cytoskeletal integrity regulate BMSC chondrogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 217, 145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yoshida N., Ogata T., Tanabe K., Li S., Nakazato M., Kohu K., Takafuta T., Shapiro S., Ohta Y., Satake M., Watanabe T. (2005) Filamin A-bound PEBP2β/CBFβ is retained in the cytoplasm and prevented from functioning as a partner of the Runx1 transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 1003–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coffman J. A. (2003) Runx transcription factors and the developmental balance between cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell Biol. Int. 27, 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Okuda T., Nishimura M., Nakao M., Fujita Y. (2001) RUNX1/AML1: a central player in hematopoiesis. Int. J. Hematol. 74, 252–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Okuda T., van Deursen J., Hiebert S. W., Grosveld G., Downing J. R. (1996) AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis. Cell 84, 321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huang G., Shigesada K., Ito K., Wee H. J., Yokomizo T., Ito Y. (2001) Dimerization with PEBP2β protects RUNX1/AML1 from ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation. EMBO J. 20, 723–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]