Abstract

Background

Self-management support interventions such as the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) are becoming more widespread in attempt to help individuals better self-manage chronic disease.

Objective

To systematically assess the clinical effectiveness of self-management support interventions for persons with chronic diseases.

Data Sources

A literature search was performed on January 15, 2012, using OVID MEDLINE, OVID MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID EMBASE, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Wiley Cochrane Library, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database for studies published between January 1, 2000, and January 15, 2012. A January 1, 2000, start date was used because the concept of non-disease-specific/general chronic disease self-management was first published only in 1999. Reference lists were examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Review Methods

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing self-management support interventions for general chronic disease against usual care were included for analysis. Results of RCTs were pooled using a random-effects model with standardized mean difference as the summary statistic.

Results

Ten primary RCTs met the inclusion criteria (n = 6,074). Nine of these evaluated the Stanford CDSMP across various populations; results, therefore, focus on the CDSMP.

Health status outcomes: There was a small, statistically significant improvement in favour of CDSMP across most health status measures, including pain, disability, fatigue, depression, health distress, and self-rated health (GRADE quality low). There was no significant difference between modalities for dyspnea (GRADE quality very low). There was significant improvement in health-related quality of life according to the EuroQol 5-D in favour of CDSMP, but inconsistent findings across other quality-of-life measures.

Healthy behaviour outcomes: There was a small, statistically significant improvement in favour of CDSMP across all healthy behaviours, including aerobic exercise, cognitive symptom management, and communication with health care professionals (GRADE quality low).

Self-efficacy: There was a small, statistically significant improvement in self-efficacy in favour of CDSMP (GRADE quality low).

Health care utilization outcomes: There were no statistically significant differences between modalities with respect to visits with general practitioners, visits to the emergency department, days in hospital, or hospitalizations (GRADE quality very low).

All results were measured over the short term (median 6 months of follow-up).

Limitations

Trials generally did not appropriately report data according to intention-to-treat principles. Results therefore reflect “available case analyses,” including only those participants whose outcome status was recorded. For this reason, there is high uncertainty around point estimates.

Conclusions

The Stanford CDSMP led to statistically significant, albeit clinically minimal, short-term improvements across a number of health status measures (including some measures of health-related quality of life), healthy behaviours, and self-efficacy compared to usual care. However, there was no evidence to suggest that the CDSMP improved health care utilization. More research is needed to explore longer-term outcomes, the impact of self-management on clinical outcomes, and to better identify responders and non-responders.

Plain Language Summary

Self-management support interventions are becoming more common as a structured way of helping patients learn to better manage their chronic disease. To assess the effects of these support interventions, we looked at the results of 10 studies involving a total of 6,074 people with various chronic diseases, such as arthritis and chronic pain, chronic respiratory diseases, depression, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Most trials focused on a program called the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP). When compared to usual care, the CDSMP led to modest, short-term improvements in pain, disability, fatigue, depression, health distress, self-rated health, and health-related quality of life, but it is not possible to say whether these changes were clinically important. The CDSMP also increased how often people undertook aerobic exercise, how often they practiced stress/pain reduction techniques, and how often they communicated with their health care practitioners. The CDSMP did not reduce the number of primary care doctor visits, emergency department visits, the number of days in hospital, or the number of times people were hospitalized. In general, there was high uncertainty around the quality of the evidence, and more research is needed to better understand the effect of self-management support on long-term outcomes and on important clinical outcomes, as well as to better identify who could benefit most from self-management support interventions like the CDSMP.

Background

In July 2011, the Evidence Development and Standards (EDS) branch of Health Quality Ontario (HQO) began developing an evidentiary framework for avoidable hospitalizations. The focus was on adults with at least 1 of the following high-burden chronic conditions: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary artery disease (CAD), atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke, diabetes, and chronic wounds. This project emerged from a request by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care for an evidentiary platform on strategies to reduce avoidable hospitalizations.

After an initial review of research on chronic disease management and hospitalization rates, consultation with experts, and presentation to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC), the review was refocused on optimizing chronic disease management in the outpatient (community) setting to reflect the reality that much of chronic disease management occurs in the community. Inadequate or ineffective care in the outpatient setting is an important factor in adverse outcomes (including hospitalizations) for these populations. While this did not substantially alter the scope or topics for the review, it did focus the reviews on outpatient care. HQO identified the following topics for analysis: discharge planning, in-home care, continuity of care, advanced access scheduling, screening for depression/anxiety, self-management support interventions, specialized nursing practice, and electronic tools for health information exchange. Evidence-based analyses were prepared for each of these topics. In addition, this synthesis incorporates previous EDS work, including Aging in the Community (2008) and a review of recent (within the previous 5 years) EDS health technology assessments, to identify technologies that can improve chronic disease management.

HQO partnered with the Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) Research Institute and the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the selected interventions in Ontario populations with at least 1 of the identified chronic conditions. The economic models used administrative data to identify disease cohorts, incorporate the effect of each intervention, and estimate costs and savings where costing data were available and estimates of effect were significant. For more information on the economic analysis, please contact either Murray Krahn at murray.krahn@theta.utoronto.ca or Ron Goeree at goereer@mcmaster.ca.

HQO also partnered with the Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis (CHEPA) to conduct a series of reviews of the qualitative literature on “patient centredness” and “vulnerability” as these concepts relate to the included chronic conditions and interventions under review. For more information on the qualitative reviews, please contact Mita Giacomini at giacomin@mcmaster.ca.

The Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Outpatient (Community) Setting mega-analysis series is made up of the following reports, which can be publicly accessed at http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ohtas-reports-and-ohtac-recommendations.

Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Outpatient (Community) Setting: An Evidentiary Framework

Discharge Planning in Chronic Conditions: An Evidence-Based Analysis

In-Home Care for Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Community: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Continuity of Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Advanced (Open) Access Scheduling for Patients With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Screening and Management of Depression for Adults With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Self-Management Support Interventions for Persons With Chronic Diseases: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Specialized Nursing Practice for Chronic Disease Management in the Primary Care Setting: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Electronic Tools for Health Information Exchange: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Health Technologies for the Improvement of Chronic Disease Management: A Review of the Medical Advisory Secretariat Evidence-Based Analyses Between 2006 and 2011

Optimizing Chronic Disease Management Mega-Analysis: Economic Evaluation

How Diet Modification Challenges Are Magnified in Vulnerable or Marginalized People With Diabetes and Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Chronic Disease Patients’ Experiences With Accessing Health Care in Rural and Remote Areas: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Patient Experiences of Depression and Anxiety With Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Experiences of Patient-Centredness With Specialized Community-Based Care: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Objective of Analysis

To systematically assess the clinical effectiveness of self-management support interventions for persons with chronic diseases.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Managing a chronic disease is a complex process that typically requires individuals to manage a number of health-related factors themselves; some diseases, such as diabetes, require near total self-care. As a result, patient programs have been developed to provide support to individuals with chronic diseases and help them self-manage their condition as effectively as possible. This support can be collectively viewed as “self-management support.” With prevalence rates of chronic diseases expected to rise as Ontario’s population ages, there is increasing need and demand for self-management support.

The target population of this review is adults (> 18 years of age) with chronic disease. While there are many self-management interventions that are developed for specific chronic diseases, this review focuses on interventions meant to support the self-management of chronic disease in general (i.e., interventions that are not disease-specific).

Technique

Self-Management Support

In simplest terms, self-management describes what a person does to manage his/her disease, and self-management support describes what health care professionals, health care practices, and the health care system provide to assist patients in their self-management. (1) In practice and in peer-reviewed literature, however, the term self-management is often used interchangeably with concepts such as self-care, patient education, patient empowerment, health coaching, motivational interviewing, integrated disease management, and others.

For the purpose of this review, self-management support is defined in accordance with the Institute of Medicine as “the systematic provision of education and supportive interventions by health care staff to increase patients’ skills and confidence in managing their health problems, including regular assessment of progress and problems, goal setting, and problem-solving support.” (2)

Not only does this definition highlight the fact that self-management support is more than just education, it also helps to illustrate the primary causal mechanism underlying many modern self-management support programs: that such programs lead primarily to changes in self-efficacy (i.e., an individual’s confidence in managing his/her condition), and changes in health care behaviour are secondary. It is believed that changes in self-efficacy directly influence health status, which in turn affects health care utilization. (3)

The Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program

The Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) is a community-based self-management support program first described by Lorig. (4) It is based on Bandura’s self-efficacy theory, a social cognitive theory that states that successful behaviour change requires confidence in one’s ability to carry out an action (i.e., self-efficacy) and the expectation that a specific goal will be achieved (i.e., outcome expectancy). The CDSMP incorporates strategies suggested by Bandura to enhance self-efficacy.

The content and methodology of the CDSMP was based on 2 needs assessments: a literature review of existing disease-specific patient education programs, and focus groups including participants aged 40 years or older with chronic disease. (4)

The exact methodology of the CDSMP differs depending on how it is implemented, but the program typically consists of 6 weekly sessions of 2½ hours each. Sessions involve groups of 10 to 15 participants and are often conducted in community settings such as churches, senior’s centres, libraries, or hospitals. Sessions are led by 2 trained volunteer laypersons (typically with chronic diseases themselves) who act more as facilitators rather than as lecturers. Rather than prescribing specific behaviour changes, leaders assist participants in making their own disease management choices to reach self-selected goals. (4)

Topics covered in the CDSMP include exercise; use of cognitive symptom management (cognitive stress/pain reduction techniques such as positive thinking or progressive muscle relaxation); use of community resources; use of medications; dealing with emotions of fear, anger, and depression; communication with others, including health professionals; problem-solving; and decision-making. (4) Exact content, however, may vary depending on how the CDSMP is implemented or adapted. Modified versions of the CDSMP—such as the culturally tailored Hispanic Tomando Control de su Salud or an Internet-based version of the CDSMP—have been successfully implemented and evaluated in clinical trials. These modified programs may translate the material of the original CDSMP into different languages, or they may add, remove, or tailor specific components to facilitate implementation for a specified user base. Modifications, however, are typically minor.

Licensing and training are required in order for external organizations to implement the CDSMP. Licensing fees range from $500 (US) to $1500 (US) (depending on the number of participants and leaders). Training fees range from $900 (US) to $1600 (US) for on-site training, up to $16,000 (US) for off-site training.

Ontario Context

As of January 2010, there were 52 licences for the CDSMP in Ontario. Involvement at the local level through Local Health Integrated Networks (LHINs) has been variable, although most LHINs have identified self-management as a priority. In the Greater Toronto Area, the Ontario Patient Self-Management Network (OPSMN) helps to coordinate patient self-management activities and provides momentum for this approach to be more widely accepted in Ontario health care. The OPSMN is made up of various Toronto-based organizations, associations, and hospitals.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Question

What is the effectiveness of self-management support interventions for persons with chronic disease compared to usual care?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on January 15, 2012, using OVID MEDLINE, OVID MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID EMBASE, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Wiley Cochrane Library, and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database for studies published between January 1, 2000, and January 15, 2012. A January 1, 2000, start date was used because the concept of non-disease-specific/general chronic disease self-management was refined and first published only in 1999. (4) Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English language full-reports

published between January 1, 2000, and January 15, 2012

randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses

trial participants 18 years or older

general chronic disease population (i.e., trial included a population of individuals with 1 or more of at least 3 different chronic diseases) (subjective determination)

self-management intervention as defined by the Australian state government of Victoria’s Self-Management Mapping Guide1 (5)

intervention performed on the patient

control group given usual care (defined as care provided by the usual care provider)

Exclusion Criteria

non-English studies

non-primary reports

Outcomes of Interest

disease-specific outcomes

health care utilization

health-related quality of life

health status measures

mortality

patient satisfaction

self-efficacy

Statistical Analysis

Measures of Treatment Effect

All outcomes across included trials were obtained from validated self-report questionnaires. Because similar outcomes were often measured using different questionnaires, the standardized mean difference (SMD) of change from baseline was used as the preferred summary statistic.

To interpret the resulting SMDs in this report, one may follow Cohen’s suggested convention that an SMD of 0.2 be interpreted as a small effect, an SMD of 0.5 as a medium effect, and an SMD of 0.8 as a large effect. (6) This approach has been suggested in a previous systematic review of self-management support interventions. (7) Still, such judgements may not be appropriate for self-report outcomes such as those reported in this review. Cohen’s convention should therefore be viewed as a guidance rather than as a rule. To aid interpretation, SMDs were back-transformed to weighted mean differences (WMDs) where interpretation on the original scale would be easy or where minimally clinically important differences had been established.

Meta-Analyses

Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.1.7 (8) according to a random effects model. Intention-to-treat (ITT) data were used when available, but few reported results according to ITT principles. The majority instead reported “available case analyses,” which included only participants whose outcome status was recorded. For this review, ITT analysis was taken to mean that participants were compared within the groups to which they were originally randomized, regardless of whether they received the treatment, withdrew, or deviated from the study protocol. (9)

When primary data for meta-analysis were not available from trial publications, they were obtained from a recent systematic review, (7) in which the authors contacted trial authors to obtain primary data or ITT data.

For meta-analyses involving the trial by Jerant et al, (10) the standard deviation of the difference in mean change from baseline between the self-management and control arms was calculated using a range of imputed correlation coefficients in a sensitivity analysis (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, and 0.95). Across all meta-analyses incorporating data from this trial, the summary SMD was not significantly impacted by varying the correlation coefficient. Reported base case analyses assumed a conservative correlation coefficient estimate of 0.5. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted across each outcome by removing certain studies when justified (as indicated in Appendix 4). Removal of these studies rarely impacted the SMD. Six-month (rather than 12-month) data were used for this trial across meta-analyses to ensure consistency with other trials.

Quality of Evidence

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the GRADE Working Group criteria. (11) The overall quality was determined to be very low, low, moderate, or high using a step-wise, structural methodology.

Study design was the first consideration; the starting assumption was that randomized controlled trials are high quality, whereas observational studies are low quality. Five additional factors—risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—were then taken into account. Limitations in these areas resulted in downgrading the quality of evidence. Finally, 3 main factors that may raise the quality of evidence were considered: large magnitude of effect, dose response gradient, and accounting for all residual confounding factors. (11) For more detailed information, please refer to the latest series of GRADE articles. (11)

As stated by the GRADE Working Group, the final quality score can be interpreted using the following definitions:

| High | Very confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect |

| Moderate | Moderately confident in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

| Low | Confidence in the effect estimate is limited—the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

| Very Low | Very little confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

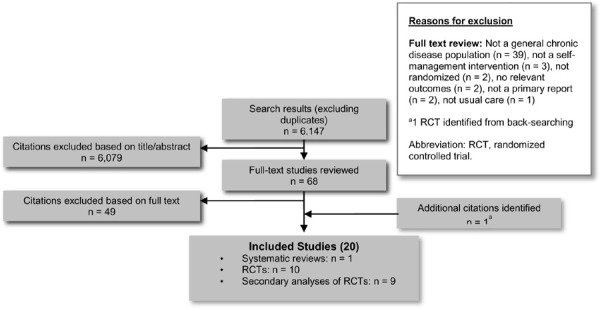

The database search yielded 6,147 citations published between January 1, 2000, and January 15, 2012 (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded based on information in the title and/or abstract (assessed simultaneously). The full texts of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further assessment. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of when and for what reason citations were excluded in the analysis.

Figure 1: Citation Flow Chart.

Eighteen studies (9 primary RCTs and 9 secondary analyses of RCTs) (10;12-28) and 1 systematic review (7) met the inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the included studies and non-systematic reviews were hand-searched to identify any additional potentially relevant studies, and 1 additional citation (primary RCT) (4) was included, for a total of 20 included citations.

For each included study, the study design was identified and is summarized below in Table 1, which is a modified version of a hierarchy of study design by Goodman. (29)

Table 1: Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design.

| Study Design | Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|

| RCT Studies | |

| Systematic review of RCTs | 1 |

| Large RCT | 10a |

| Small RCT | |

| Observational Studies | |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with contemporaneous controls | |

| Non-RCT with non-contemporaneous controls | |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with historical controls | |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | |

| Database, registry, or cross-sectional study | |

| Case series | |

| Retrospective review, modelling | |

| Studies presented at an international conference | |

| Expert opinion | |

| Total | 11a |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Nine additional publications reported secondary analyses of the 10 primary RCTs.

One systematic review was identified for inclusion. The review, by Foster et al, (7) was published by the Cochrane Collaboration and evaluated self-management education programs by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. It was published in 2009 but reported on publications dated up to July 28, 2006. It included studies of self-management programs in both disease-specific and general chronic disease populations, and thus its conclusions do not apply to this review, but some of the data were used for meta-analysis (see Statistical Analysis, above).

Study Descriptions

Ten primary RCTs were identified for inclusion, including a total of 6,074 people with chronic diseases. (4;10;12-19) Study design characteristics, participant characteristics, and intervention characteristics are summarized in the text below and fully described in Appendix 2 (Tables A1, A2, and A3).

Table A1: Study Design Characteristics.

| Study, Year | Country | Design | Arms, n | Attrition, % | Recruitment | Length of Follow-up | Patient Eligibility Criteria | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lorig et al, 1999 (4) | United States | Single-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 1,140 SM: 664 UC: 476 Completed Total: 952 SM: 561 UC: 391 |

15.1 SM 17.9 UC |

|

6 months |

Chronic diseases: physician-confirmed asthma, CAD, CHF, chronic arthritis, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or stroke Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of above chronic diseases Exclusion criteria: compromised mentation; received chemotherapy or radiation within past year for cancer; < 40 years age |

Waiting-list control |

| Fu et al, 2003 (17) | China | Single-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 954 SM: 526 UC: 428 Completed Total: 779 SM: 430 UC: 349 |

18.3 SM 18.5 UC |

|

6 months |

Chronic diseases: medical record-confirmed arthritis, asthma, CAD, CHF, chronic bronchitis, diabetes, emphysema, hypertension, or stroke Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of above chronic diseases; ≥ 20 years age Exclusion criteria: compromised mentation; received chemotherapy or radiation within past year for cancer; patients for whom problems could be expected with compliance or follow-up; participation in another study in previous 30 days; stroke with severe physical disability ;< 20 years of age |

Waiting-list control |

| Lorig et al, 2003 (15) | United States | Single-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 551 SM: 327 UC: 224 Completed Total: 443 SM: 265 UC: 178 |

19.0 SM 20.5 UC |

|

4 months |

Chronic diseases: physician-confirmed (self-reported if physician unavailable) heart disease, lung disease, or type 2 diabetes Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of above chronic diseases Exclusion criteria: treated for cancer in last year |

Waiting-list control |

| Griffiths et al, 2005 (19) | United Kingdom | Double-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 476 SM: 238 UC: 238 Completed Total: 439 SM: 221 UC: 218 |

7.1 SM 8.4 UC |

|

4 months |

Chronic diseases: registry-confirmed arthritis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or respiratory disease Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of above chronic diseases; Bangladeshi; > 20 years age |

Waiting-list control |

| Lorig et al, 2006 (14) | United States | Non-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 958 SM: 457 UC: 501 Completed Total: 780 SM: 354 UC: 426 |

22.5 SM 17.6 UC |

|

12 months |

Chronic diseases: physician-confirmed chronic lung disease, heart disease, or type 2 diabetes Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of above chronic diseases; ≥ 18 years age; no active treatment for cancer; not ever participated in small-group CDSMP; access to a computer; agreed to 1-2 hours per week of log-on time spread over at least 3 sessions per week for 6 weeks; able to complete online questionnaire |

Care from usual provider |

| Swerissen et al, 2006 (16) | Australia | Non-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 728 SM: 467 UC: 261 Completed Total: 474 SM: 320 UC: 154 |

31.5 SM 41.0 UC |

|

6 months |

Chronic diseases: physician-confirmed chronic illness (not defined) or chronic pain Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of above chronic diseases; ≥ 18 years age; Italian, Greek, Vietnamese, or Chinese; live within municipal areas of Boroondara, Darebin, Hume, Greater Dandenong, Yarra, or Whittlesea Exclusion criteria: < 18 years age; primary illness psychological or advanced neurological disorder |

Waiting-list control |

| Elzen et al, 2007 (18) | Netherlands | Non-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 144 SM: 70 UC: 74 Completed Total: 129 SM: 67 UC: 62 |

4.3 SM 16.2 UC |

|

6 months |

Chronic diseases: angina pectoris, arthritis, asthma, CHF, COPD, diabetes (unclear how diagnosis confirmed) Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of the above chronic diseases; ≥59 years of age; ability to communicate in Dutch; availability to attend a 6-week course Exclusion criteria: life expectancy of less than 1 year; already attending a disease-specific self-management program; participating in another study; permanent residents of a nursing home |

Waiting-list control |

| Kennedy et al, 2007 (12) | United Kingdom | Non-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 629 SM: 313 UC: 316 Completed Total: 521 SM: 248 UC: 273 |

20.8 SM 13.6 UC |

|

6 months |

Chronic diseases: self-reported chronic condition (not defined) Inclusion criteria: 1 or more self-reported chronic condition |

Waiting-list control |

| Jerant et al, 2009 (10) | United States | Non-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 415 Intervention A: 138 Intervention B: 139 UC: 138 Completed Total: 415 Intervention A: 138 Intervention B: 139 UC: 138 |

15.9 SM 14.4 T 7.2 UC |

|

12 months |

Chronic diseases: physician-confirmed arthritis, asthma, COPD, CHF, depression, or diabetes Inclusion criteria: 1 or more of above chronic disease; ≥40 years age; ability to speak and read in English; residence in a private home with active telephone; eyesight and hearing adequate; at least 1 activity impairment assessed by the HAQ and/or a score of ≥4 on the 10-item CES-D |

Care from their usual provider |

| Hochhalter et al, 2010 (13) | United States | Single-blind RCT |

Randomized Total: 79 SM: 26 Safety group: 27 UC: 26 Completed Total: 64 SM: 20 Safety group: 23 UC: 21 |

23.1 SM 14.8 S 19.2 UC |

|

6 months |

Chronic diseases: ICD-9 diagnosis arthritis, depression, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, lung disease, or osteoporosis Inclusion criteria: received treatment for at least 2 of the above chronic conditions in the previous 12 months; ≥ 65 years age; can communicate in English; has access to telephone; expected to receive most of their care within the health care system for at least 8 months prior to baseline Exclusion criteria: diagnosed with dementia; receiving hospice care; unable to travel to clinic; living outside of the recruitment area |

Care from usual care provider |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CDSMP, Chronic Disease Self-Management Program; CES–D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EPP, Expert Patient Programme; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition; RCT, randomized controlled trial; S, safety arm; SM, self-management arm; T, telephone arm; UC, usual care arm.

Table A2: Patient Characteristics.

| Study, Year | Minority Population (Country) | Chronic Disease | Confirmed Diagnosis | Mean Diseases, n | Mean Age, years | Female, % | White, % | Married, % | Mean Education, years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lorig et al, 1999 (4) | General population (United States) | ≥ 1of 7 defined conditions | Yes | 2.2 SM 2.3 UC |

65.6 SM 65.0 UC |

65.0 SM 64.0 UC |

91.4 SM 88.7 UC |

54.0 SM 55.1 UC |

15.0 SM 15.0 UC |

| Fu et al, 2003 (17) | General population (China) | ≥ 1of 9 defined conditions | Yes | 2.1 SM 2.0 UC |

64.2 SM 63.9 UC |

73.3 SM 69.1 UC |

— | 82.3 SM 79.4 UC |

9.5 SM 9.9 UC |

| Lorig et al, 2003 (15) | Hispanic population (United States) | ≥ 1of 3 defined conditions | Yes | 1.9 SM 1.7 UC |

56.6 SM 56.1 UC |

79.5 SM 79.5 UC |

— | 56.9 SM 52.7 UC |

— |

| Griffiths et al, 2005 (19) | Bangladeshi population (United Kingdom) | ≥ 1of 4 defined conditions | Yes | — | 48.9 SM 48.0 UC |

55.9 SM 58.4 UC |

— | 85.7 SM 87.4 UC |

— |

| Lorig et al, 2006 (14) | General population (United States) | ≥ 1of 3 defined conditions | Yes | — | 57.6 SM 57.4 UC |

71.6 SM 71.2 UC |

88.7 SM 87.2 UC |

63.6 SM 67.8 UC |

15.8 SM 15.4 UC |

| Swerissen et al, 2006 (16) | Italian, Greek, Vietnamese, or Chinese (Australia) | ≥ 1of 2 defined conditionsa | Yes | 2.2 SM 2.00 UC |

66.4 SM 65.4 UC |

72.8 SM 79.2 UC |

— | 72.2 SM 76.6 UC |

7.1 SM 6.2 UC |

| Elzen et al, 2007 (18) | General population (Netherlands) | ≥ 1of 6 defined conditions | Unclear | — | 68.2 SM 68.5 UC |

63.2 SM 63.2 UC |

— | — | — |

| Kennedy et al, 2007 (12) | General population (United Kingdom) | 1 defined conditionb | No | — | 55.5 SM 55.3 UC |

70.0 SM 69.6 UC |

95.2 SM 94.6 UC |

60.1 SM 60.1 UC |

7.8 SM 7.5 UC |

| Jerant et al, 2009 (10) | General population (United States) | ≥ 1of 6 defined conditions | No | — | 59.8 SM 61.2 T 60.1 UC |

78.3 SM 78.4 T 75.4 UC |

74.6 SM 79.1 T 83.3 UC |

57.2 SM 56.8 T 55.0 UC |

— |

| Hochhalter et al, 2010 (13) | General population (United States) | ≥ 1of 7 defined conditions | Yes | 3.6 SM 3.3 safety 3.8 UC |

76.0 SM 73.0 S 73.0 UC |

65.4 SM 66.7 S 65.4 UC |

— | — | — |

Abbreviations: S, safety arm; SM, self-management arm; T, telephone arm; UC, usual care arm.

Chronic diseases defined as chronic pain and chronic illness (both were defined as written and thus encompassed many different chronic conditions).

Chronic diseases defined as self-reported long-term health condition (thus encompassed many different chronic conditions).

Table A3: Intervention Characteristics.

| Study, year | Name of Intervention | Setting | Intensity (number of episodes/duration of episode, min/total duration, weeks) | Delivery | Content | Provider | Tailored to Initial Assessmenta | Follow-up Assessment and Modificationb | Baseline Supplementc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lorig et al, 1999 (4) | CDSMP | Group Patient with family | 7/150/7 | Face-to-face Written | Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Lay leaders | No | Yes | No |

| Fu et al, 2003 (17) | Modified CDSMP | Group | 7/150/7 | Face-to-face Written | Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Lay leaders Other |

No | Yes | No |

| Lorig et al, 2003 (15) | Tomando Control de su Salud (modified CDSMP) | Group Patient with family | 6/150/6 | Audio Face-to-face Written | Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Lay leaders | No | Yes | No |

| Griffiths et al, 2005 (19) | Modified CDSMP | Group | 6/180/6 | Face-to-face Video |

Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Self-management Social support (6 of 8) |

Lay leaders | No | Yes | No |

| Lorig et al, 2006 (14) | Internet-based CDSMP | Individual | 18/90/6 | Internet Written |

Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Lay leaders | No | Yes | No |

| Swerissen et al, 2006 (16) | Modified CDSMP | Group | 6/150/6 | Audio Face-to-face Written |

Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Lay leaders | No | Yes | No |

| Elzen et al, 2007 (18) | Modified CDSMP | Group | 6/150/6 | Face-to-face Written |

Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Psychologist | No | Yes | No |

| Kennedy et al, 2007 (12) | Modified-CDSMP (EPP) | Group | 6/150/6 | Face-to-face Written |

Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Lay leaders | No | Yes | No |

| Jerant et al, 2009 (10) | Home-based CDSMP (HIOH) | Individual | 6/120/6 | Face-to-face Telephone Written |

Communication with providers Lifestyle (diet, exercise) Medication management Psychological Symptom management Self-management Social support (7 of 8) |

Lay leaders Nurse |

No | Yes | No |

| Hochhalter et al, 2010 (13) | Making the Most of Your Healthcare | Group | 1/120/1 | Face-to-face Telephone |

Communication with providers Self-management Social support (3 of 8) |

Research staff | No | Yes | No |

Abbreviations: CDSMP, Chronic Disease Self-Management Program; EPP, Expert Patient Programme; HIOH, Homing in on Health.

Describes whether the intervention was personally tailored based on an initial assessment.

Describes whether participants in the intervention were followed during the course of intervention or afterwards, and whether their treatment was modified according to follow-up assessments.

Describes whether both intervention and control were provided with some form of baseline supplement.

Nine additional secondary analyses of the primary RCTs were also identified. (20-28) The results of these trials are described briefly.

Intervention

Nine of the 10 primary RCTs evaluated the Stanford CDSMP across various populations. (4;10;12;14-19) The remaining trial investigated the Making the Most of Your Healthcare intervention, a patient engagement intervention that met the definition of self-management support for this review. (13) This review will focus on papers investigating the Stanford CDSMP.

All trials, except for the original CDSMP trial by Lorig et al, (4) modified the original CDSMP to tailor the program to a specific user base. Six trials modified the CDSMP to account for cultural/language differences, (12;15-19) 1 trial employed an Internet-based version of the CDSMP, (14) and 1 trial employed a home-based version of the CDSMP. (10)

Setting

Four of the 9 CDSMP trials were conducted in the United States, (4;10;14;15) 2 in the United Kingdom, (12;19) 1 in the Netherlands, (18) 1 in China, (17) and 1 in Australia. (16)

Recruitment

Seven of the 9 CDSMP trials recruited participants from the community via an advertising campaign employing flyers, newsletters, magazine ads, and other community outreach methods (i.e., patients therefore self-selected themselves for study). (4;10;12;14-17) Three studies recruited from primary care/outpatient clinics via direct invitation. (10;18;19)

Participants

The mean age of participants across all 9 CDSMP trials was 60.0 years. (4;10;12;14-19) Participants were largely female (mean 69.9%, number of studies [N] = 9), (4;10;12;14-19) married (mean 66.6%, N = 8), (4;10;12;14-17;19) and living with more than 1 chronic condition (mean number of conditions 2.07, N = 4). (4;15-17) Among the trials in a non-minority population that reported race, participants were largely white (mean 86.6%, N = 4). (4;10;12;14) Lastly, 2 trials reported that participants had more than 15 years of education, (4;14) and 3 trials reported that participants had fewer than 10 years of education. (12;16;17)

Chronic Conditions

Most trials specified a set number of defined conditions as eligible chronic diseases. Only 2 trials did not define eligible chronic diseases. (12;16) Six trials required physician-confirmed diagnosis of disease, (4;14-17;19), 2 trials required only patient-reported diagnosis, (10;12) and in 1 trial, disease confirmation was unclear. (18)

Results by Health Status Outcome

Across all health status outcomes but dyspnea, there was a statistically significant benefit in favour of self-management compared to usual care (see Appendices 3 and 4).

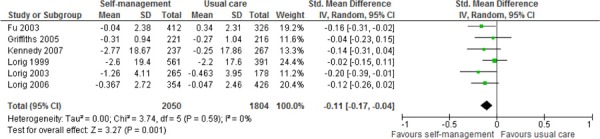

Pain

Data on change in pain from baseline were available for 7 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A1). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant reduction in pain in favour of CDSMP (SMD, -0.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.17, -0.04; P = 0.001). (4;12;14;15;17;19) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (P = 0.001). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A1: Change in Pain From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

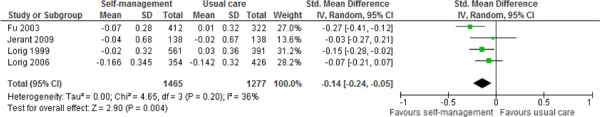

Disability

Data on change in disability from baseline were available for 5 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A2). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant reduction in disability in favour of CDSMP (SMD, -0.14; 95% CI, -0.24, -0.05, P = 0.004). (4;10;14;17) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found no statistically significant difference between the CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.43), but the direction of benefit favoured CDSMP. The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A2: Change in Disability From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

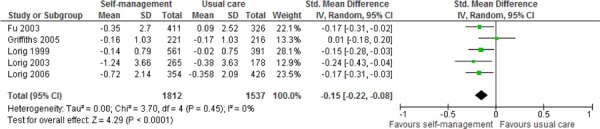

Fatigue

Data on change in fatigue from baseline were available for 6 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A3). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant reduction in fatigue in favour of CDSMP (SMD, -0.15; 95% CI, -0.22, -0.08; P < 0.001). (4;14;15;17;19) One trial was not included in the metaanalysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (P = 0.02). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A3: Change in Fatigue From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Dyspnea

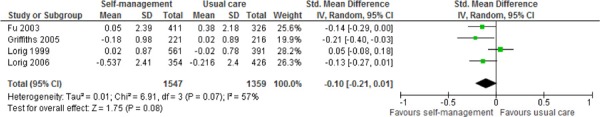

Data on change in shortness of breath from baseline were available for 5 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A4). Meta-analysis showed a non-significant trend towards reduction in shortness of breath in favour of CDSMP (SMD, -0.10; 95% CI, -0.21, 0.01; P = 0.08). (4;14;17;19) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found no statistically significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.67), but the direction of benefit favoured CDSMP. The GRADE score for this body of evidence was very low.

Figure A4: Change in Dyspnea From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Depression

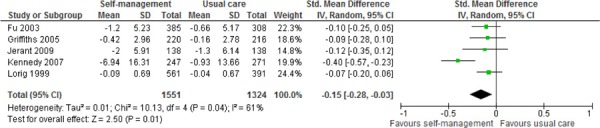

Data on change in depression from baseline were available for 6 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A5). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant reduction in depression in favour of CDSMP (SMD, -0.15; 95% CI, -0.28, -0.03; P = 0.01). (4;10;12;17;19) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found no statistically significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.42), but the direction of benefit favoured CDSMP. The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A5: Change in Depression From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Health Distress

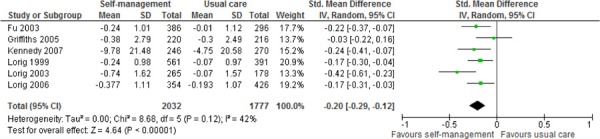

Data on change in health distress from baseline were available for 7 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A6). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant reduction in health distress in favour of CDSMP (SMD, -0.20; 95% CI, -0.29, -0.12; P < 0.001). (4;12;14;15;17;19) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (P = 0.04). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A6: Change in Health Distress From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

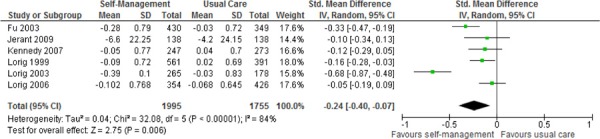

Self-Rated Health

Data on change in self-rated health from baseline were available for 7 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A7). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant reduction (lower is better) in self-rated health in favour of CDSMP (SMD, -0.24; 95% CI, -0.40, -0.07; P = 0.006). (4;12;14;15;17;19) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (P < 0.001). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A7: Change in Self-Rated Health From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Data on health-related quality of life were sparsely reported and difficult to interpret collectively.

Two studies showed no significant difference between CDSMP and usual care for mean change from baseline scores on the Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary (P > 0.05) of the SF-36 (GRADE score very low). (10;18)

One study found a significant benefit in mean change from baseline scores for the EuroQOL Visual Analogue Scale in favour of CDSMP (P = 0.03) (GRADE score low). (10)

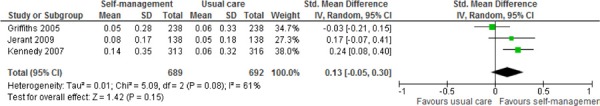

Finally, 3 studies reported on change from baseline scores on the EuroQoL 5D (EQ-5D). (10;12;19) A meta-analysis including all 3 studies showed a non-significant trend towards benefit in favour of CDSMP (SMD, 0.13; 95% CI, -0.05, 0.30; P = 0.15) (GRADE score very low) (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A8); however, sensitivity analysis removing the study by Griffiths et al (conducted in a minority Bangladeshi population for which the EQ-5D may not apply) (19) revealed a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (SMD, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.09, 0.35; P = 0.001 / WMD, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.00, 0.10; P = 0.04) (GRADE score moderate).

Figure A8: Change in HR-QOL (EQ-5D) From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EQ-5D, EuroQoL-5D; HR-QOL, health-related quality of life; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Evaluating the evidence of EQ-5D separately should also be considered, since inclusion of the study by Jerant et al (10) in the meta-analysis required imputation. This study found no significant difference between home-based CDSMP and usual care (P > 0.05) (GRADE score very low), whereas the study by Kennedy et al, (12) a large pragmatic RCT conducted in the United Kingdom, found a significant benefit in favour of a culturally adapted group-based CDSMP compared to usual care (SMD, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.08, 0.40; P = 0.003 / WMD, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.03, 0.13; P = 0.003) (GRADE score moderate). Minimally important differences of 0.10 and 0.07 have been suggested for United Kingdom-based and United States-based EQ-5D scores, respectively, for individuals with cancer. (30)

Results by Healthy Behaviour Outcome

Aerobic Exercise

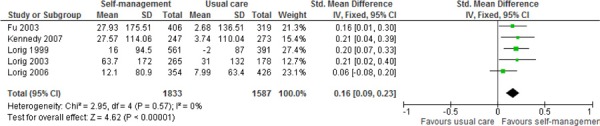

Data on change in aerobic exercise from baseline were available for 7 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A9). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant increase in aerobic exercise in favour of CDSMP (SMD, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.09, 0.23; P < 0.001). (4;12;14;15;17) Two trials were not included in the meta-analysis. The first trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (P = 0.005). The second trial, by Elzen et al, (18) found no significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.47). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A9: Change in Aerobic Exercise From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Cognitive Symptom Management

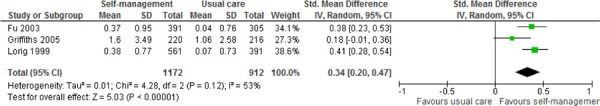

Data on change in cognitive symptom management from baseline were available for 5 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A10). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant increase in cognitive symptom management (higher is better) in favour of CDSMP (SMD, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.20, 0.47; P < 0.001). (4;17;19) Two trials were not included in the meta-analysis. The first trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (P < 0.001). The second trial, by Elzen et al, (18) found no significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.14). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A10: Change in Cognitive Symptom Management From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Communication With Health Care Professionals

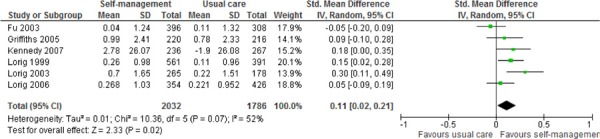

Data on change in communication from baseline were available for 7 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A11). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant increase in communication (higher is better) in favour of CDSMP (SMD, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.02, 0.21; P = 0.02). (4;12;14;15;17;19) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Elzen et al, (18) found no significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.48). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A11: Change in Communication With Health Care Professionals From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

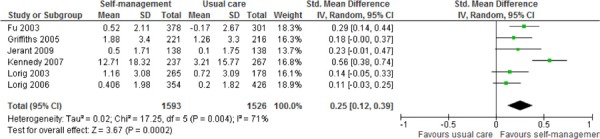

Results on Self-Efficacy

Data on change in self-efficacy from baseline were available for 8 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A12). Meta-analysis showed a small statistically significant increase in self-efficacy (higher is better) in favour of CDSMP (SMD, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.12, 0.39; P = 0.002). (10;12;14;15;17;19) Two trials were not included in the meta-analysis. The first trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found a statistically significant benefit in favour of CDSMP (P < 0.001). The second trial, by Elzen et al, (18) found no significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.06). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was low.

Figure A12: Change in Self-Efficacy From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Results by Health Care Utilization Outcome

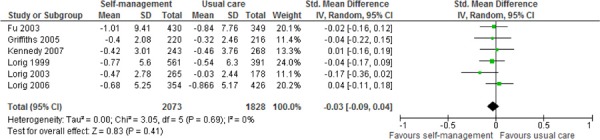

Visits With General Practitioners

Data on change in general practitioner visits from baseline were available for 7 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A13). Meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the CDSMP and usual care (SMD, -0.03; 95% CI, -0.09, 0.04; P = 0.41). (4;12;14;15;17;19) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found no significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.24). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was very low.

Figure A13: Change in Visits With General Practitioners From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

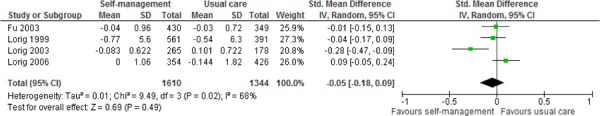

Visits to the Emergency Department

Data on change in emergency department visits from baseline were available for 5 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A14). Meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the CDSMP and usual care (SMD, -0.05; 95% CI, -0.18, 0.09; P = 0.49). (4;14;15;17) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Swerissen et al, (16) found no significant difference between the CDSMP and usual care (P = 0.68). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was very low.

Figure A14: Change in Visits to the Emergency Department From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

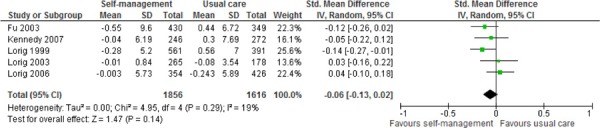

Days in Hospital

Data on change in days in hospital from baseline were available for 5 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A15). Meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the CDSMP and usual care (SMD, -0.06; 95% CI, -0.13, 0.02; P = 0.14 / WMD, -0.27; 95% CI, -0.75, 0.20; P = 0.26). (4;12;14;15;17) However, sensitivity analyses removing the Internet-based CDSMP study by Lorig et al (14) revealed a minor statistically significant reduction in favour of CDSMP for the SMD (SMD, -0.09; 95% CI, -0.16, -0.01; P = 0.02), but not for the WMD (WMD, -0.42; 95% CI, -0.97, 0.13; P = 0.14). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was very low.

Figure A15: Change in Days in Hospital From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Hospitalizations

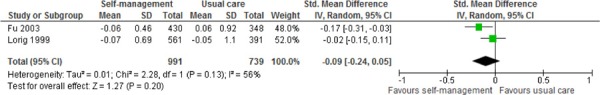

Data on change in hospitalizations visits from baseline were available for 3 studies (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4, Figure A16). Meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the CDSMP and usual care (SMD, -0.09; 95% CI, -0.24, 0.05; P = 0.20). (4;17) One trial was not included in the meta-analysis; this trial, by Jerant et al, (10) found no significant difference between CDSMP and usual care (P = NR). The GRADE score for this body of evidence was very low.

Figure A16: Change in Hospitalizations From Baseline for Self-Management Versus Usual Care.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, instrumental variables; SD, standard deviation.

Secondary Analyses (Who Benefits From Self-Management?)

Nine studies conducted secondary analyses of the data from several of the primary RCTs. (20-28) Many of these studies attempted to identify moderators or predictors of response to the CDSMP. In general, analyses were not identified a priori, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, and results were inconsistent across studies and varied according by outcome. The data were therefore difficult to interpret and should be viewed as hypothesis-generating only. Future trials that prospectively stratify patients based on hypothesized predictors of response should be conducted to better confirm these findings.

Conclusions

Low quality evidence showed that the Stanford CDSMP led to statistically significant, albeit clinically minimal, short-term (median 6 months) improvements across a number of health status measures, in healthy behaviours, and self-efficacy compared to usual care.

Very low quality evidence showed no significant difference between the CDSMP and usual care in short-term (median 6 months) health care utilization and across some health-related quality of life scales.

Moderate quality evidence showed that the CDSMP led to statistically significant, albeit clinically minimal, short-term (median 6 months) improvement in EQ-5D score compared to usual care.

More research is needed to explore the long-term (12 months and greater) effect of self-management across outcomes and to explore the impact of self-management on clinical outcomes.

Exploratory evidence suggests that some subgroups of persons with chronic conditions may respond better to the CDSMP; however, there is considerable uncertainty, and more research is needed to better identify responders and non-responders.

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Jeanne McKane, CPE, ELS(D)

Medical Information Services

Kaitryn Campbell, BA(H), BEd, MLIS

Kellee Kaulback, BA(H), MISt

Expert Panel for Health Quality Ontario: Optimizing Chronic Disease Management in the Community (Outpatient) Setting

| Name | Title | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Shirlee Sharkey (chair) | President & CEO | Saint Elizabeth Health Care |

| Theresa Agnew | Executive Director | Nurse Practitioners’ Association of Ontario |

| Onil Bhattacharrya | Clinician Scientist | Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto |

| Arlene Bierman | Ontario Women’s Health Council Chair in Women’sHealth | Department of Medicine, Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto |

| Susan Bronskill | Scientist | Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences |

| Catherine Demers | Associate Professor | Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, McMaster University |

| Alba Dicenso | Professor | School of Nursing, McMaster University |

| Mita Giacomini | Professor | Centre of Health Economics & Policy Analysis, Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics |

| Ron Goeree | Director | Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) Research Institute, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton |

| Nick Kates | Senior Medical Advisor | Health Quality Ontario – QI McMaster University Hamilton Family Health Team |

| Murray Krahn | Director | Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative, University of Toronto |

| Wendy Levinson | Sir John and Lady Eaton Professor and Chair | Department of Medicine, University of Toronto |

| Raymond Pong | Senior Research Fellow and Professor | Centre for Rural and Northern Health Research and Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Laurentian University |

| Michael Schull | Deputy CEO & Senior Scientist | Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences |

| Moira Stewart | Director | Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, University of Western Ontario |

| Walter Wodchis | Associate Professor | Institute of Health Management Policy and Evaluation, University of Toronto |

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Search date: January 15th, 2012

Databases searched: OVID MEDLINE, OVID MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, OVID EMBASE, Wiley Cochrane, EBSCO CINAHL, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.

Limits: 2000-present; English; NOT comments, editorials, letters, conference abstracts (Embase); MA/SR/HTA filter

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to January Week 1 2012>, Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations <January 13, 2012>, Embase <1980 to 2012 Week 02>

Search Strategy:

Search run 2012Jan15

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Coronary Artery Disease/ | 211560 |

| 2 | exp Myocardial Infarction/ use mesz | 133322 |

| 3 | exp heart infarction/ use emez | 216531 |

| 4 | (coronary artery disease or cad or heart attack).ti. | 44367 |

| 5 | ((myocardi* or heart or cardiac or coronary) adj2 (atheroscleros* or arterioscleros* or infarct*)).ti. | 149359 |

| 6 | or/1-5 | 538869 |

| 7 | exp Atrial Fibrillation/ use mesz | 27983 |

| 8 | exp heart atrium fibrillation/ use emez | 55357 |

| 9 | ((atrial or atrium or auricular) adj1 fibrillation*).ti,ab. | 73222 |

| 10 | or/7-9 | 99066 |

| 11 | exp heart failure/ | 300018 |

| 12 | ((myocardi* or heart or cardiac) adj2 (failure or decompensation or insufficiency)).ti,ab. | 233907 |

| 13 | 11 or 12 | 380815 |

| 14 | exp Stroke/ | 177469 |

| 15 | exp Ischemic Attack, Transient/ use mesz | 16352 |

| 16 | exp transient ischemic attack/ use emez | 19630 |

| 17 | exp stroke patient/ use emez | 5626 |

| 18 | exp brain infarction/ or exp cerebrovascular accident/ use emez | 100838 |

| 19 | (stroke or tia or transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular apoplexy or cerebrovascular accident or cerebrovascular infarct* or brain infarct* or CVA).ti,ab. | 280281 |

| 20 | or/14-19 | 390464 |

| 21 | exp Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2/ use mesz | 67951 |

| 22 | exp non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus/ use emez | 101327 |

| 23 | exp diabetic patient/ use emez | 12828 |

| 24 | (diabetes or diabetic* or niddm or t2dm).ti,ab. | 763121 |

| 25 | or/21-24 | 787988 |

| 26 | exp Skin Ulcer/ | 71910 |

| 27 | ((pressure or bed or skin) adj2 (ulcer* or sore* or wound*)).ti,ab. | 28604 |

| 28 | (decubitus or bedsore*).ti,ab. | 8513 |

| 29 | or/26-28 | 90561 |

| 30 | exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/ use mesz | 16974 |

| 31 | exp chronic obstructive lung disease/ use emez | 54556 |

| 32 | (chronic obstructive adj2 (lung* or pulmonary or airway* or airflow or respiratory) adj (disease* or disorder*)).ti,ab. | 54256 |

| 33 | (copd or coad).ti,ab. | 45380 |

| 34 | chronic airflow obstruction.ti,ab. | 1062 |

| 35 | exp Emphysema/ | 37368 |

| 36 | exp chronic bronchitis/ use emez | 6962 |

| 37 | ((chronic adj2 bronchitis) or emphysema).ti,ab. | 50761 |

| 38 | or/30-37 | 158839 |

| 39 | exp Chronic Disease/ | 340238 |

| 40 | (chronic*adj2 disease* or (chronic* adj2 ill*)).ti,ab. | 32284 |

| 41 | 39 or 40 | 358737 |

| 42 | exp Comorbidity/ | 143035 |

| 43 | (comorbid* or co-morbid* or multimorbid* or multi-morbid* or (complex* adj patient*) or “patient* with multiple” or (multiple adj2 (condition* or disease*))).ti,ab. | 202574 |

| 44 | 42 or 43 | 283057 |

| 45 | 6 or 10 or 13 or 20 or 25 or 29 or 38 or 41 or 44 | 2703456 |

| 46 | exp Self Care/ use mesz | 33960 |

| 47 | Self-Help Groups/ use mesz | 7150 |

| 48 | exp Consumer Participation/ use mesz | 27930 |

| 49 | Self Efficacy/ use mesz | 9213 |

| 50 | exp Self Care/ use emez | 39454 |

| 51 | Self Concept/ use emez | 49189 |

| 52 | Self Injection/ use emez | 709 |

| 53 | Self Monitoring/ use emez | 2895 |

| 54 | Patient Participation/ use emez | 13365 |

| 55 | Empowerment/ use emez | 1619 |

| 56 | (selfadminist* or selfcar* or selfinject* or selfmanag* or selfmeasur* or selfmedicat* or selfmonitor* or selfregulat* or selftest* or selftreat*).ti,ab. | 1197 |

| 57 | (self-administ* or self-car* or self-inject* or self-manag* or self-measur* or self-medicat* or self-monitor* or self-regulat* or self-test*OR self-treat*).ti,ab. | 106600 |

| 58 | (selfactivation or selfdevelop* or selfintervention).ti,ab. | 11 |

| 59 | (self-activation or self-develop* or self-intervention).ti,ab. | 1876 |

| 60 | ((patient? or consumer?) adj 3 (activation or coach* or empowerment or involv* or participat*)).ti,ab. | 115250 |

| 61 | health coach*.ti,ab. | 200 |

| 62 | ((behaviour* adj (coach* or modif*)) or (behavior* adj (coach* or modif*))).ti,ab. | 6962 |

| 63 | (dsmp or cdsmp or dsme or smp or sme or smt).ti,ab. | 5738 |

| 64 | (medication? adherence adj5 self*).ti,ab. | 497 |

| 65 | or/46-64 | 375121 |

| 66 | 45 and 65 | 56078 |

| 67 | exp Technology Assessment, Biomedical/ or exp Evidence-based Medicine/ use mesz | 63340 |

| 68 | exp Biomedical Technology Assessment/ or exp Evidence Based Medicine/ use emez | 522432 |

| 69 | (health technology adj2 assess*).ti,ab. | 3053 |

| 70 | exp Random Allocation/ or exp Double-Blind Method/ or exp Control Groups/ or exp Placebos/ use mesz | 378960 |

| 71 | Randomized Controlled Trial/ or exp Randomization/ or exp RANDOM SAMPLE/ or Double Blind Procedure/ or exp Triple Blind Procedure/ or exp Control Group/ or exp PLACEBO/ use emez | 900130 |

| 72 | (random* or RCT).ti,ab. | 1252730 |

| 73 | (placebo* or sham*).ti,ab. | 413329 |

| 74 | (control* adj2 clinical trial*).ti,ab. | 35016 |

| 75 | meta analysis/ use emez | 58505 |

| 76 | (meta analy* or metaanaly* or pooled analysis or (systematic* adj2 review*) or published studies or published literature or medline or embase or data synthesis or data extraction or cochrane).ti,ab. | 251967 |

| 77 | or/67-76 | 2160203 |

| 78 | limit 66 to (controlled clinical trial or meta analysis or randomized controlled trial) | 6134 |

| 79 | 66 and 77 | 12038 |

| 80 | or/78-79 | 12410 |

| 81 | limit 80 to yr=“2000 -Current” | 10499 |

| 82 | Case Reports/ or Comment.pt. or Editorial.pt. or Letter.pt. use mesz | 2907283 |

| 83 | Case Report/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or Conference Abstract.pt. use emez | 5789547 |

| 84 | or/82-83 | 5893868 |

| 85 | 81 not 84 limit 85 to english language Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to January Week 1 2012> (3625) |

9453 |

| 86 | Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations <January 13, 2012> (193) Embase <1980 to 2012 Week 02> (5011) | 8829 |

CINAHLSearch run 2012Jan15

| # | Query | Limiters/Expanders | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| S53 | S34 and S48 and S51 | Limiters – Published Date from: 20000101-20121231; English Language; Exclude MEDLINE records Search modes – Boolean/Phrase |

296 |

| S52 | S34andS48and S51 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 1889 |

| S51 | S49 or S50 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 156231 |

| S50 | random* or sham*or rct* or health technology N2 assess* or meta analy* or metaanaly* or pooled analysis or (systematic* N2 review*) or published studies or medline or embase or data synthesis or data extraction or cochrane or control* N2 clinical trial* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 148184 |

| S49 | (MH “Random Assignment”) or (MH “Random Sample+”) or (MH “Meta Analysis”) or (MH “Systematic Review”) or (MH “Double-Blind Studies”) or (MH “Single-Blind Studies”) or (MH “Triple-Blind Studies”) or (MH “Placebos”) or (MH “Control (Research)”) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 82924 |

| S48 | S35 or S36 or S37 or S38 or S39 or S40 or S41 or S42 or S43 or S44 or S45 or S46 or S47 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 60430 |

| S47 | medication? adherence N5 self* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 39 |

| S46 | dsmp OR cdsmp OR dsme OR smp OR sme OR smt | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 278 |

| S45 | (behaviour* N1 (coach* OR modif*)) OR (behavior* N1 (coach* OR modif*)) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 1893 |

| S44 | health coach* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 171 |

| S43 | (patient? OR consumer?) N3 (activation OR coach* OR empowerment OR involv* OR participat*) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 8663 |

| S42 | self-activation OR self-develop* OR self-intervention | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 231 |

| S41 | selfactivation OR selfdevelop* OR selfintervention | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 2 |

| S40 | self-administ* OR self-car* OR self-inject* OR self-manag* OR self-measur* OR self-medicat* OR self-monitor* OR self-regulat* OR self-test*OR self-treat* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 30327 |

| S39 | selfadminist* OR selfcar* OR selfinject* OR selfmanag* OR selfmeasur* OR selfmedicat* OR selfmonitor* OR selfregulat* OR selftest* OR selftreat* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 184 |

| S38 | (MH “Self-Actualization”) OR (MH “Self-Efficacy”) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 6981 |

| S37 | (MH “Consumer Participation”) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 8416 |

| S36 | (MH “Support Groups”) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 5563 |

| S35 | (MH “Self Care+”) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 19424 |

| S34 | S5 OR S8 OR S11 OR S15 OR S19 OR S22 OR S27 OR S30 OR S33 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 213351 |

| S33 | S31 OR S32 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 28632 |

| S32 | comorbid* or co-morbid* or multimorbid* or multi-morbid* or (complex* N1 patient*) or “patient* with multiple” or (multiple N2 (condition* or disease*)) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 28632 |

| S31 | MH “Comorbidity” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 16495 |

| S30 | S28 OR S29 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 28085 |

| S29 | chronic*N2 disease* OR chronic* N2 ill* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 7551 |

| S28 | MH “Chronic Disease” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 23522 |

| S27 | S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 8672 |

| S26 | chronic N2 bronchitis OR emphysema | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 1803 |

| S25 | MH “Emphysema” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 879 |

| S24 | chronic obstructive N2 disease* OR chronic obstructive N2 disorder* OR copd OR coad | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 7262 |

| S23 | MH “Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive+” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 5272 |

| S22 | S20 OR S21 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 16060 |

| S21 | pressure N1 ulcer* OR bedsore* OR bed N1 sore* OR skin N1 ulcer* OR pressure N1 wound* OR decubitus | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 9508 |

| S20 | MH “Skin Ulcer+” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 14728 |

| S19 | S16 OR S17 OR S18 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 69574 |

| S18 | diabetes OR diabetic* OR niddm OR t2dm | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 69574 |

| S17 | MH “Diabetic Patients” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 3491 |

| S16 | MH “Diabetes Mellitus, Non-Insulin-Dependent” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 18090 |

| S15 | S12 OR S13 OR S14 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 38043 |

| S14 | stroke OR tia OR transient ischemic attack OR cerebrovascular apoplexy OR cerebrovascular accident OR cerebrovascular infarct* OR brain infarct* OR CVA | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 37551 |

| S13 | MH “Cerebral Ischemia, Transient” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 1892 |

| S12 | (MH “Stroke”) OR (MH “Stroke Patients”) | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 25516 |

| S11 | S9 OR S10 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 19135 |

| S10 | myocardi* failure OR myocardial decompensation OR myocardial insufficiency OR cardiac failure OR cardiac decompensation OR cardiac insufficiency OR heart failure OR heart decompensation OR heart insufficiency | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 19123 |

| S9 | MH “Heart Failure+” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 14335 |

| S8 | S6 OR S7 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 7966 |

| S7 | atrial N1 fibrillation* OR atrium N1 fibrillation* OR auricular N1 fibrillation* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 7966 |

| S6 | MH “Atrial Fibrillation” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 6441 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 30356 |

| S4 | TI myocardi* N2 infarct* OR TI heart N2 infarct* OR TI cardiac N2 infarct* OR TI coronary N2 infarct* OR TI arterioscleros* OR TI atheroscleros* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 9573 |

| S3 | coronary artery disease OR cad OR heart attack* | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 7885 |

| S2 | MH “Myocardial Infarction+” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 19390 |

| S1 | MH “Coronary Arteriosclerosis” | Search modes – Boolean/Phrase | 4639 |

Wiley Cochrane

Search run 2012Jan15

Avoidable Hospitalization – Self-Management: KC

| ID | Search | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | MeSH descriptor Coronary Artery Disease explode all trees | 2104 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor Myocardial Infarction explode all trees | 7637 |

| #3 | (myocardi* or heart or cardiac or coronary) NEAR/2 (atheroscleros* or arterioscleros* or infarct*):ti or (coronary artery disease or cad or heart attack*):ti | 8384 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor Atrial Fibrillation explode all trees | 2056 |

| #5 | (atrial NEAR/2 fibrillation* or atrium NEAR/2 fibrillation* or auricular NEAR/2 fibrillation* ):ti | 2268 |

| #6 | MeSH descriptor Heart Failure explode all trees | 4620 |

| #7 | (myocardi* NEAR/2 (failure or decompensation or insufficiency)):ti or (heart NEAR/2 (failure or decompensation or insufficiency)):ti or (cardiac NEAR/2 (failure or decompensation or insufficiency)):ti | 5180 |

| #8 | MeSH descriptor Stroke explode all trees | 3791 |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor Ischemic Attack, Transient explode all trees | 459 |

| #10 | (stroke or tia or transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular apoplexy or cerebrovascular accident or cerebrovascular infarct* or brain infarct* or CVA):ti | 9821 |

| #11 | MeSH descriptor Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2 explode all trees | 6799 |

| #12 | (diabetes or diabetic* or niddm or t2dm):ti | 16337 |

| #13 | MeSH descriptor Skin Ulcer explode all trees | 1555 |

| #14 | (pressure or bed or skin) NEAR/2 (ulcer* or sore* or wound*):ti | 662 |

| #15 | (decubitus or bedsore*):ti | 98 |

| #16 | MeSH descriptor Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive explode all trees | 1714 |

| #17 | (chronic obstructive NEAR/2 (lung* or pulmonary or airway* or airflow or respiratory) ):ti | 2397 |

| #18 | (copd or coad):ti | 3303 |

| #19 | (chronic airflow obstruction):ti | 72 |

| #20 | MeSH descriptor Emphysema explode all trees | 90 |

| #21 | (chronic NEAR/2 bronchitis) or emphysema:ti | 1180 |

| #22 | MeSH descriptor Chronic Disease explode all trees | 9770 |

| #23 | (chronic* NEAR/2 disease* or chronic* NEAR/2 ill*):ti | 1643 |

| #24 | MeSH descriptor Comorbidity explode all trees | 1902 |

| #25 | (comorbid* OR co-morbid* OR multimorbid* OR multi-morbid* OR (complex* NEXT patient*) OR “patient* with multiple” OR (multiple NEAR/2 (condition* OR disease*))):ti | 638 |

| #26 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25) | 67251 |

| #27 | MeSH descriptor Self Care explode all trees | 2973 |

| #28 | MeSH descriptor Self-Help Groups, this term only | 495 |

| #29 | MeSH descriptor Consumer Participation explode all trees | 840 |

| #30 | MeSH descriptor Self Efficacy explode all trees | 1136 |

| #31 | (selfadminist* OR selfcar* OR selfinject* OR selfmanag* OR selfmeasur* OR selfmedicat* OR selfmonitor* OR self-regulat* OR selftest* OR selftreat*):ti or (self-administ* OR self-car* OR self-inject* OR self-manag* OR self-measur* OR self-medicat* OR self-monitor* OR self-regulat* OR self-test*OR self-treat*):ti or (selfactivation OR selfdevelop* OR selfintervention):ti or (self-activation OR self-develop* OR self-intervention):ti or (patient? OR consumer?) NEAR/3 (activation OR coach* OR empowerment OR involv* OR participat*):ti | 2031 |

| #32 | (health coach*):ti or (behaviour* NEXT (coach* OR modif*)) OR (behavior* NEXT (coach* OR modif*)):ti or (dsmp OR cdsmp OR dsme OR smp OR sme OR smt):ti or (medication? adherence NEAR/5 self*):ti | 186 |

| #33 | (#27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32) | 6380 |

| #34 | (#26 AND #33) | 1381 |

| #35 | (#26 AND #33), from 2000 to 2012 | 1155 |

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

Search run 2012Jan15

| Line | Search | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR coronary artery disease EXPLODE ALL TREES | 230 |

| 2 | (coronary artery disease or cad or heart attack*):TI | 211 |

| 3 | ((myocardi* or heart or cardiac or coronary) adj2 (atheroscleros* or arterioscleros* or infarct*)):TI | 223 |

| 4 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Atrial Fibrillation EXPLODE ALL TREES | 225 |

| 5 | (((atrial or atrium or auricular) adj1 fibrillation*):TI | 0 |

| 6 | ((atrial or atrium or auricular) adj1 fibrillation*):TI | 167 |

| 7 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR heart failure EXPLODE ALL TREES | 418 |

| 8 | ((myocardi* or heart or cardiac) adj2 (failure or decompensation or insufficiency)):TI | 279 |

| 9 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR stroke EXPLODE ALL TREES | 549 |

| 10 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Ischemic Attack, Transient EXPLODE ALL TREES | 32 |

| 11 | (stroke or tia or transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular apoplexy or cerebrovascular accident or cerebrovascular infarct* or brain infarct* or CVA):TI | 621 |

| 12 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2 EXPLODE ALL TREES | 511 |

| 13 | (diabetes or diabetic* or niddm or t2dm):TI | 1220 |

| 14 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Skin Ulcer EXPLODE ALL TREES | 253 |

| 15 | ((pressure or bed or skin) adj2 (ulcer* or sore* or wound*)):TI | 73 |

| 16 | (decubitus or bedsore*):TI | 0 |

| 17 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive EXPLODE ALL TREES | 237 |

| 18 | (chronic obstructive adj2 (lung* or pulmonary or airway* or airflow or respiratory) ):TI | 218 |

| 19 | (copd or coad):TI | 107 |

| 20 | (chronic airflow obstruction):TI | 0 |

| 21 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Emphysema EXPLODE ALL TREES | 10 |

| 22 | ((chronic adj2 bronchitis) or emphysema):TI | 47 |

| 23 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Chronic Disease EXPLODE ALL TREES | 687 |

| 24 | (chronic*adj2 disease* or (chronic* adj2 ill*)):TI | 21 |

| 25 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Comorbidity EXPLODE ALL TREES | 146 |

| 26 | (comorbid* OR co-morbid* OR multimorbid* OR multi-morbid* OR (complex* adj1 patient*) OR “patient* with multiple” OR (multiple adj2 (condition* OR disease*))):TI | 22 |

| 27 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 | 4571 |

| 28 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Self Care EXPLODE ALL TREES | 326 |

| 29 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Self-Help Groups | 57 |

| 30 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Consumer Participation EXPLODE ALL TREES | 76 |

| 31 | MeSH DESCRIPTOR Self Efficacy | 25 |

| 32 | (selfadminist* OR selfcar* OR selfinject* OR selfmanag* OR selfmeasur* OR selfmedicat* OR selfmonitor* OR selfregulat* OR selftest* OR selftreat*):TI OR (self-administ* OR self-car* OR self-inject* OR self-manag* OR self-measur* OR self-medicat* OR self-monitor* OR self-regulat* OR self-test*OR self-treat*):TI OR (selfactivation OR selfdevelop* OR selfintervention):TI OR (self-activation OR self-develop* OR self-intervention):TI OR ((patient? OR consumer?) ADJ3 (activation OR coach* OR empowerment OR involv* OR participat*)):TI | 26 |

| 33 | (health coach*):TI OR ((behaviour* ADJ1 (coach* OR modif*)) OR (behavior* ADJ1 (coach* OR modif*))):TI OR (dsmp OR cdsmp OR dsme OR smp OR sme OR smt):TI OR (medication? adherence ADJ5 self*):TI | 2 |

| 34 | #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 | 468 |

| 35 | #27 AND #34 | 155 |

| 36 | #27 AND #34 FROM 2000 TO 2012 | 146 |

Appendix 2: Study and Patient Characteristics