Abstract

Despite its importance to care, clinicians and researchers often discount patient-reported outcomes in favor of proxy reports, in persons with traumatic brain injury (TBI). The rationale relates to concerns about lack of awareness of patients regarding their functioning. However, although lack of awareness occurs in some patients with severe TBI, or in TBI involving certain lesion locations, or very soon after injury, this conclusion has been overgeneralized. The objective of this study is to determine the validity of patient-reported health-related quality of life by evaluating its relationship to injury severity and more objective indices of outcome, in a representative series of adults with TBI. A consecutive sample of 374 persons with TBI at least 14 years old, and having a post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤12, an acute seizure, or a CT scan showing TBI- related findings. Seventy-six percent (374/491) of the eligible survivors were assessed at 6 months post-injury on the Life Satisfaction Survey. The greatest decrease in satisfaction was in the ability to think and remember, work, receive adequate income, and participate in leisure and recreational activities. Dissatisfaction significantly related to the functional limitation in that area as judged by the patients themselves (p<0.001) or by someone who knew them well (p≤0.001). The most severely injured group reported the most dissatisfaction for 13 out of 17 areas assessed. Patients with TBI, in general, do not need a proxy to report on their behalf regarding their functional limitations or health-related quality of life.

Key words: awareness, brain injuries, quality of life

Introduction

Extensive research over the last 30 years has focused on neuropsychological and functional status outcomes following traumatic brain injury (TBI). Less is known about TBI survivors' view of their quality of life or their assessment of their subjective well-being and factors that are related to it. However, interest in patient-reported outcomes has increased, as has their use in a variety of roles including improvement in patient–clinician communication and evaluation of treatment effectiveness.1

The goal of patient-reported outcomes is to evaluate the patient perspective in a reliable, valid, and acceptable way.2,3 Much work has been done on quality of life and its measurement in a variety of health-related conditions. However, when evaluating quality of life in patients with central nervous system conditions, including those with TBI, clinicians and researchers often question the use of patient reports, because of the possibility of patients' unawareness of their deficits.4,5 The perception is that objective indices of functioning are only weakly related to self-reported quality of life in TBI subjects.6,7 Further, some have found that mental health is the strongest predictor of perceived quality of life.8–11 If such results are verified in prospective, representative series of TBI, then the validity of self-reported quality of life in TBI can be questioned, at least as it relates to objective indices of functioning. The purpose of this study is to examine perceived quality of life following TBI in a representative series of subjects, and examine whether it is related to brain injury severity and more objective indices of outcome, as evaluated by the patients themselves and those that know them well.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects on this study participated in one of two National Institutes of Health (NIH)-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)-funded clinical trials of acute treatments following TBI that prospectively followed participants from the day of injury through at least 6 months after injury. Participants were at least 14 years of age and had either post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)12 score of ≤12; an acute seizure; or a CT scan showing an acute epidural, subdural, or intracerebral hematoma, cortical contusion, depressed skull fracture, or penetrating brain injury. Detailed inclusion exclusion criteria and outcome for the trials (valproic acid [VPA] and magnesium) have been reported previously.13–15 Neither study treatment had any effect on quality of life measures at 6 months post-injury (unpublished data from our laboratory).

This article reports quality of life findings of those who took these measures at 6 months after injury; 643 participants were enrolled during the period when these measures were given at 6 month follow-up and 118 (18%) died, 34 (5%) were too impaired to take the measures, 85 (13%) were lost to follow-up, and 32 (5%) were not tested for other reasons. Those who were too impaired to take the measures were either in a vegetative state at 6 months post-injury (n=10) or were rated as having lower severe disability on the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOS-E)16 (n=20) used in the magnesium study, or severe disability on the GOS17 (n=4) that was used in the VPA Study. Seventy-six percent (374/ 491) of the eligible testable survivors were evaluated at 6 months post-injury.

Demographic information on the included subjects demonstrated that 78% of the participants were male and 79% were white. The average age was 31.2 (SD=14.2) and average education was 11.65 years (SD=2.2). The average GCS score obtained in the emergency department was 8.2 (SD=3.5). Sixty percent of the participants had a GCS score of 3–8, 22% had a score of 9–12, and 18% had a score of 13–15 with CT findings.

The study was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

Significant others

Significant Others (SOs) were people who knew the TBI subject well before and after the injury. In the VPA study, SOs were parents (42%), spouses (23%), other relatives (16%; e.g., sibling, offspring), or unrelated friends/mates (20%). This information was not collected for the magnesium study. A total of 332 SOs participated in the study.

Measures

Severity

GCS12 is a measure of the depth of coma evaluated in the emergency department. GCS scores were categorized into severe (GCS 3–8), moderate (GCS 9–12), and complicated mild (GCS 13–15 with CT abnormality) severity groups.

Functional status

GOS-E16 is the extended version of the GOS,17 a widely used functional measure of outcome following TBI. This measure evaluates level of dependence on others and the ability to live normally. Based on a structured interview, the patient is classified into an eight category scale ranging from death to upper good recovery. This revised version attempts to improve the sensitivity of the GOS to outcome by increasing the categories from 5 to 8 and by providing more explicit classification criteria. The rating was based on the best available sources of information (e.g. the participant, the participant's SO, medical personnel). Data are available for 269 participants because the original version (GOS) was administered to the subjects on the VPA study.

Functional Status Examination (FSE)18 is a measure that evaluates changes in functional status as a result of the TBI. The measure covers physical (personal care, ambulation, and travel), social (work, home management, leisure and recreation, social integration, and financial independence), and psychological (cognitive and behavioral competency) domains. The information is obtained through a structured interview. These areas are evaluated using the concept of dependency to operationally define outcome at four levels: no change from pre-injury, difficulty in performing the activity although still independent, dependence on others some of the time or not performing substantial activities in the area, and completely dependent on others or unable to perform that activity at all. The FSE was administered separately to the TBI subject and the SO 6 months after the TBI. The patient FSE had a test–retest correlation of 0.80 at 6 months post-injury when the retest was administered by telephone by a different examiner 2–3 weeks later, and the correlation between patient and SO FSE was also 0.80.18

Life Satisfaction Survey (LSS)

This measure was developed by us to parallel the FSE described previously, but with focus on satisfaction with various areas of life. Some of the items came from the Perceived Quality of Life,19 whereas others were based on items from the Sickness Impact Profile20 and on our research and clinical experience with persons with TBI.

The LSS measures the TBI subject's degree of satisfaction with 17 different areas of life such as working or ability to walk or travel. The scores range from 0 (not satisfied at all) to 100 (extremely satisfied). Current satisfaction level for a particular area of life in the previous month was rated first, and then degree of satisfaction for that area before the injury was rated. Item change scores were calculated by subtracting the pre-injury rating from the rating of current satisfaction. Therefore, a negative change score indicated less satisfaction at 6 months post-injury than pre-injury, whereas a positive change score indicated improvement in satisfaction. In addition, two summary scores were calculated; the average current satisfaction rating and the average change score, both of which were calculated by summing the 17 items (current satisfaction ratings or change scores) and dividing by 17. The LSS includes nine areas that parallel domains evaluated on the FSE (i.e., personal care, ambulation, travel, work, home management, leisure and recreation, social integration, cognition, and income) and eight distinct areas. The LSS, previously referred to as the Modified Perceived Quality of Life Scale, showed a systematic and significant relationship (p<0.001) with the FSE at 3–5 years post-TBI,21 and showed significant (p<0.01) improvement when used as an outcome measure evaluating a telephone-based counseling intervention following TBI.22 Test–retest reliability for the average change in satisfaction score was 0.88 (Spearman ρ) when administered by phone 2–3 weeks after the 6 month evaluation by a different examiner (unpublished data from our laboratory).

Statistical analysis

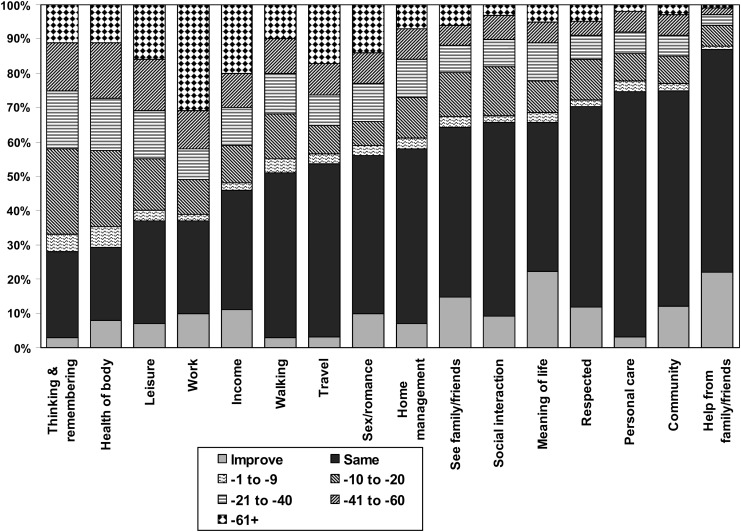

Change in satisfaction from pre-to post-injury for each area on the LSS was summarized descriptively using stacked bar graphs. For figures and tables, items are arranged in order from the area with the most to that with the least dissatisfaction in the overall group.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the relationship between change in satisfaction on each item of the LSS and TBI severity and 6 month functional level. Comparisons of change in satisfaction and the TBI participant and the SO assessment of functional status were made with the LSS items that parallel the FSE items. Analyses of satisfaction with work by FSE group were restricted to those for whom the activity was applicable (e.g., worker at the time of the injury or at 6 months or would have been a worker post-injury). Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) was used for pairwise comparisons of subgroups when the ANOVA indicated significant differences. A significant difference is indicated by the means for both pair members having the same letter as superscript. A significance level of 0.001 was used because of the large number of comparisons; however, differences with p values between 0.001 and 0.05 are marked for readers who prefer a less conservative approach.

Results

Stacked bar graphs depicting the distribution of change in satisfaction at 6 months post-injury compared with before the injury for the entire group are shown in Figure 1. Areas of greatest dissatisfaction included the ability to think and remember, health of the body, ability to perform leisure and recreation activities, work, and whether income met needs. More than 50% of TBI subjects reported being less satisfied with their functioning in these areas than before the injury, and ≥25% of the sample reported being >40 points less satisfied on a scale ranging from 0 to 100. Areas where at least 75% showed some increase or no change in satisfaction at 6 months post-injury compared with before the injury included help from family and friends, and contribution to the community.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of change in satisfaction.

The results of ANOVAs comparing change in satisfaction by TBI severity are presented in Table 1. Trends were seen in ability to take care of personal care needs (p<0.01), leisure and recreation activities, working/not working, sexual activity (or romantic relationships), ability to take care of homecare responsibilities, seeing family and friends, and average change in satisfaction (each p<0.05), all with the most severely injured group showing the biggest decrease in satisfaction. Surprisingly, severity did not relate to change in satisfaction with one's ability to think and remember. All three severity groups showed a drop of ∼25 points in satisfaction with their thinking and memory from pre-to post-injury.

Table 1.

Mean Change at 6 Months Post-Injury by GCS Groups

| |

GCS groups |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–8 | 9–12 | 13–15 | p | |

| n | 212 | 81 | 63 | |

| Compared with pre-injury, how satisfied are you… | ||||

| With your ability to think and remember? | −25 | −25 | −23 | 0.90 |

| With the health of your body? | −26 | −21 | −20 | 0.21 |

| With your leisure and recreation activities? | −30 | −20 | −18 | 0.01 |

| With working/not working? | −39 | −32 | −25 | 0.04 |

| That your income meets your needs? | −27 | −26 | −18 | 0.21 |

| With your ability to walk? | −22 | −16 | −14 | 0.09 |

| With your ability to travel? | −26 | −19 | −15 | 0.06 |

| With your sexual activity (or romantic relationships)? | −23 | −11 | −12 | 0.01 |

| With your ability to manage homecare? | −16 | −6 | −12 | 0.03 |

| With how much you see family and friends? | −11 | −2 | −7 | 0.04 |

| With your ability to relate to others and socially interact? | −12 | −6 | −5 | 0.05 |

| With the meaning and purpose of your life? | −6 | −4 | −6 | 0.84 |

| With how respected you are? | −7 | −7 | −3 | 0.39 |

| With your ability to take care of your personal care needs? | −11 | −3 | −3 | 0.003 |

| With your contribution to your community? | −7 | −1 | −4 | 0.16 |

| With the help you get from family and friends? | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.75 |

| Change in overall happiness | −12 | −9 | −5 | 0.18 |

| Average change in satisfaction from pre-injury | −16 | −12 | −12 | 0.04 |

| Average satisfaction now | 68 | 74 | 72 | 0.09 |

| Average satisfaction pre-injury | 85 | 86 | 84 | 0.76 |

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Mean change in satisfaction by GOSE is presented in Table 2. With a few exceptions, the ANOVAs are highly significant (p<0.001) and show systematic expected relationships between GOSE categories and change in satisfaction with subjects in the severe disability groups reporting being much less satisfied compared with pre-injury in all areas than were those in the good recovery groups.

Table 2.

Mean Change by GOS-E Rating at 6 Months Post-Injury

| |

GOS-E |

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Severe |

Moderate |

Good |

|

|||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | p | |

| n | 34 | 24 | 59 | 65 | 40 | 46 | |

| Compared with pre injury, how satisfied are you… | |||||||

| With your ability to think and remember? | −42Aef | −38B | −31C | −23df | −18e | −5ABCd | <0.001 |

| With the health of your body? | −41A | −42B | −32C | −20 | −20 | −7ABC | <0.001 |

| With your leisure and recreation activities? | −43A | −39b | −33c | −25 | −23 | −10Abc | <0.001 |

| With working/not working? | −56AD | −54be | −55CFg | −28g | −15DeF | −18AbC | <0.001 |

| That your income meets your needs? | −34 | −32 | −39a | −28 | −20 | −12a | 0.007 |

| With your ability to walk? | −41ADF | −35Beg | −28C | −13Fg | −10De | −5ABC | <0.001 |

| With your ability to travel? | −51ADG | −51BEH | −35Cfi | −14GHi | −11DEf | −2ABC | <0.001 |

| With your sexual activity (or romantic relationships)? | −41Ab | −31 | −21 | −13b | −17 | −6A | <0.001 |

| With your ability to manage homecare | −29ad | −34bce | −21 | −7de | −7c | −2ab | <0.001 |

| With how much you see family and friends? | −16 | −11 | −13 | −8 | −6 | −2 | 0.11 |

| With your ability to relate to others and socially interact? | −19ad | −21b | −18ce | −6 | −2de | 0abc | <0.001 |

| With the meaning and purpose of your life? | −16 | −15 | −9 | −1 | −6 | 2 | 0.03 |

| With how respected you are? | −14 | −13 | −9 | −7 | −8 | −1 | 0.24 |

| With your ability to take care of your personal needs? | −31ACEG | −24BdF | −8G | −2EF | −4Cd | −2AB | <0.001 |

| With your contribution to your community? | −22Abc | −7 | −7 | −3c | −3b | 5A | <0.001 |

| With the help you get from family and friends? | −3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0.62 |

| Change in overall happiness | −26A | −23b | −14 | −7 | −14 | 2Ab | <0.001 |

| Average change in satisfaction from pre-injury | −29ADG | −29BEH | −22Cfi | −12GHi | −10DEf | −2ABC | <0.001 |

| Average satisfaction now | 57Aef | 58B | 62C | 72df | 74e | 85ABCd | <0.001 |

| Average satisfaction pre-injury | 86 | 87 | 84 | 83 | 85 | 88 | 0.46 |

Subgroups marked with the same capital letters are significantly different by Tukey's post-hoc test at p<0.001. Subgroups marked with the same lower case letters are significantly different by Tukey's post-hoc test at p<0.01.

GOS-E, Glasgow Outcome Scale – Extended.

The comparison of subject change in satisfaction by subject-reported functional status on the FSE is summarized in Table 3. All ANOVAs were significant (p<0.001). Subjects who reported that they were the same as they were before the injury on the FSE reported the least change in satisfaction on average. Average levels of dissatisfaction increased as level of dependency increased. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that subjects who reported that they needed help with some activities or had dropped some activities or were completely dependent were significantly (p<0.001) less satisfied compared with pre-injury than the group who reported that they were same as before the injury.

Table 3.

Mean Change in Satisfaction Ratings by 6 Month Subject-Reported FSE Category

|

Compared with pre-injury, how satisfied are you… | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same as before | More difficult | Helped /dropped some | Helped /dropped all | p | |

| With your ability to think and remember? | −10AC | −18BD | −36CD | −43AB | <0.001 |

| With your recreation or leisure time activities? | −5AD | −11B | −29CD | −50ABC | <0.001 |

| With working/not working?a | −8Ad | −13B | −33cd | −57ABc | <0.001 |

| That your income meets your needs? | −4AB | −22 | −40B | −42A | <0.001 |

| With your ability to walk? | −3ACE | −22BDE | −44CD | −59AB | <0.001 |

| With your ability to travel? | −4AD | −9Be | −27CDe | −53ABC | <0.001 |

| With your ability to manage your homecare responsibilities? | 0AC | −7BD | −28CD | −38AB | <0.001 |

| With your ability to relate to others and socially interact? | 1AD | −5B | −15cD | −33ABc | <0.001 |

| With your ability to take care of your personal care needs? | 0ADf | −8BEf | −20CDE | −53ABC | <0.001 |

Subgroups marked with the same capital letters are significantly different by Tukey's post-hoc test at p<0.001. Subgroups marked with the same lower case letters are significantly different by Tukey's post-hoc test at p<0.01.

Restricted to those for whom the category is applicable.

FSE, Functional Status Examination.

The comparison of subject change in satisfaction by SO report of functional status on the FSE is summarized in Table 4. The results are very similar to the comparison with the subject's FSE. All ANOVAs were significant (p≤0.001)

Table 4.

Mean Change in Subject Satisfaction Ratings by 6 Month SO-Reported FSE Category

|

Compared with pre-injury, how satisfied are you… | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same as before | More difficult | Helped /dropped some | Helped /dropped all | p | |

| With your ability to think and remember? | −10AB | −23 | −31B | −38A | <0.001 |

| With your recreation or leisure time activities? | −6AC | −22 | −29bC | −44Ab | <0.001 |

| With working/not working?a | −3Ad | −20B | −32cd | −56ABc | <0.001 |

| That your income meets your needs? | −3AB | −22 | −36B | −42A | <0.001 |

| With your ability to walk? | −6ACE | −23bDE | −40CD | −44Ab | <0.001 |

| With your ability to travel? | −4AD | −11B | −25CD | −48ABC | <0.001 |

| With your ability to manage your homecare responsibilities? | −2AC | −5Bd | −22Cd | −32AB | <0.001 |

| With your ability to relate to others and socially interact? | −2a | −5 | −12a | −15 | 0.001 |

| With your ability to take care of your personal care needs? | −1AD | −7B | −14CD | −44ABC | <0.001 |

Subgroups marked with the same capital letters are significantly different by Tukey's post-hoc test at p<0.001. Subgroups marked with the same lower case letters are significantly different by Tukey's post-hoc test at p<0.01.

Restricted to those for whom the category is applicable.

SO, significant other; FSE, Functional Status Examination.

Discussion

This is the first study that examines the validity of patient report of quality of life based on a large, representative sample of patients with TBI. The findings of this study indicate that most people with TBI, even those with severe functional limitations, are aware of those deficits by 6 months after injury, and rate their satisfaction accordingly. It is important to add that the TBI severity of this sample is predominantly moderate to severe. As evaluated with the LSS, satisfaction is decreased in various activities of everyday life post-injury compared with pre-injury. The degree of dissatisfaction, however, varies by area of functioning. Areas of greatest dissatisfaction include the ability to think and remember, health of the body, employment situation, leisure and recreation, and whether income is meeting needs. Interestingly, these areas are also the ones that are commonly reported to be problematic following TBI. For example, the three top areas of dysfunction reported on the Sickness Impact Profile by complicated mild to severely injured TBI subjects and their SOs at 1 year post-injury were work, recreation and pastimes, and alertness behavior.23, 24 In addition, there is extensive literature showing the negative effects of TBI on return to work23,25–28 and not surprisingly, income is also often impacted.23 Problems with participation in leisure and recreation activities have also been reported.29–34 In contrast, some areas seem to show minimal negative impact 6 months post-injury. These include help received from family and friends, seeing family and friends, and ability to perform basic personal care activities. In fact, ≥50% of the subjects reported the same level of satisfaction before and after the injury, indicating that for the majority of subjects, satisfaction in these areas was not affected by the TBI at 6 months post-injury.

The results clearly show that TBI subject dissatisfaction post-injury is significantly and systematically related to functional status (i.e., how the person is doing) whether the functional level is a global one such as assessed on the GOS-E or specific as represented by various areas on the FSE. The latter is true whether the functional rating is by the TBI subject or by the SO. Subjects who are rated as more disabled on the GOS-E by the best source of information available (e.g., the participant, the participant's SO, medical personnel) are more dissatisfied than subjects rated as returning to normal. Furthermore, subjects rated as more dependent on the FSE by their SOs or by self-rating are also more dissatisfied than subjects rated as returning to normal. For example, subjects who are rated on the GOS-E as being in the lower severe disability group are on average 42 points less satisfied than they were before the injury in their ability to think and remember. This average drops steadily, indicating levels of satisfaction that are closer to pre-injury levels as outcome improves. Therefore, the results demonstrate that objective indicators such as functional status (reported by the subject or a proxy who knows the subject well) and subjective well-being (satisfaction) are highly and systematically related to each other. These results call into question the notion that they are unrelated to each other,35 or that the only type of variable that is strongly related to subjective well-being is another measure of subjective well-being.7 One possible reason for the discrepant findings may be the samples studied. Our results are based on a large, representative sample prospectively followed from the day of injury until 6 months post- injury. On the other hand, Cicerone and Azulay's35 study, for example, was based on a convenience sample recruited from support groups or a brain injury association or from referrals to a post-acute brain injury rehabilitation program, which may have influenced their results.

Decrease in satisfaction was also related to the severity of brain injury, as measured by GCS, but not to the same extent as observed for functional status described previously. This should not be surprising, as dissatisfaction should be more closely related to the actual or perceived loss of function than to depth of coma measured within hours of injury. However, for 13 of the 17 areas, those with severe injuries reported the greatest decrease in satisfaction. Although change in satisfaction with one's ability to think and remember was not significantly different among the severity groups, this finding may indicate marked dissatisfaction with this area in all severity groups, rather than lack of awareness for the most severely injured group. Although some may argue that this finding suggests lack of awareness of cognitive deficits given the well documented dose-response relationship between brain injury severity and performance on cognitive measures, more research is needed to untangle and address this issue. The study of “lack of awareness” in the areas of cognition and emotional health should be examined using representative samples, and by the method and criterion used to determine degree of awareness (e.g. comparison with a performance-based measure such as scores on neuropsychological measures, severity criteria such as GCS, or observations and judgment of SO). These results challenge prior reports indicating that those with the most severe injuries report the highest or best quality of life post-injury.36,37 Although lack of awareness of disability and losses does in fact occur in some individuals with severe brain injuries, this should not be generalized to most persons with severe TBI, and certainly not to persons with TBI in general.

That said, it is important to point out that conceptually, the study of subjective quality of life is inherently limited because of the impossibility of ever knowing if anyone's report of subjective quality of life is 100% accurate whether they have sustained a TBI or not. In addition, although there is a strong, systematic relationship between patient's satisfaction with outcome and assessment of functional limitations at 6 months post-injury, we also cannot claim that TBI subjects are fully aware of the underlying injury-related mechanisms or causes of their functional limitations. In addition, satisfaction with quality of life may vary depending upon the assessment method that is used.

For example, some researchers have reported better awareness of motor-sensory changes than of behavioral changes.5,38,39 It is possible that the areas that are assessed and the anchoring of questions to relatively specific descriptions of the functional area on the LSS increased the strength of the relationship between satisfaction with an area and its functional status. Although overall happiness showed a significant and systematic relationship with functional status, it is possible that as it was asked toward the end of the evaluation, the more specific earlier items influenced the answer to the overall question. However, based on the results of the LSS, this study does indicate that TBI subjects' satisfaction with their functioning or functional status can be validly ascertained by asking them, and that reliance on a proxy is not necessary.

One might be concerned that change in satisfaction might reflect more “good old days” bias,40 that is, viewing their pre-injury situation as better than it was, in the more severe or more functionally impaired, rather than lower current satisfaction. That does not seem to be the case, as the average satisfaction pre-injury shown in Tables 1 and 2 demonstrates no pattern with severity or level of functioning. Looking at change in satisfaction has the advantage of increasing sensitivity by looking at within-person change, and decreasing the effect of personality and individual characteristics. In Table 2, although both the average change and the average satisfaction now are highly significantly related to functional level, six of the pairwise comparisons are significant for satisfaction now, whereas nine are significant for change in satisfaction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that most persons with TBI can validly report on the degree of their satisfaction with their functioning. They are less satisfied with their health-related quality of life. The greatest decreases in satisfaction that they report are in ability to think and remember, work, income, and leisure and recreation. Their results closely mirror the literature regarding outcomes in TBI. Their dissatisfaction with health-related outcome in a given area closely relates to their functional limitation in that area as judged by them or someone who knows them well. These results refute the commonly held belief based on some literature and some clinical cases that those with TBI are unaware of their deficits and functional limitations. It is reasonable to expect lack of awareness soon after injury when persons with TBI may not have had the opportunity to test and be aware of their losses. Undoubtedly, there are also patients with severe TBI41 and certain lesion locations who are indeed unaware.42 However, this conclusion does not apply to the majority of persons with TBI. In general, persons with TBI do not appear to need a proxy to report on their behalf regarding their limitations or health-related quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants R01NS19643 from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), W81XWH-08-2-159 from Department of Defense (DoD) , and H133A070032 from National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR). No funding organization or sponsor was involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Higginson I.J. Carr A.J. Measuring quality of life: using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ. 2001;322:1297–1300. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzpatrick R. Davey C. Buxton M.J. Jones D.R. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol. Assess. 1998;2:1–74. i-iv. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery M.P. Perrier L.L. Acquadro C. Patient-reported outcome and quality of life instruments database (PROQOLID): frequently asked questions. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2005;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prigatano G.P. Disturbances of self-awareness and rehabilitation of patients with traumatic brain injury: a 20-year perspective. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:19–29. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart T. Sherer M. Whyte J. Polansky M. Novack T.A. Awareness of behavioral, cognitive, and physical deficits in acute traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;85:1450–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrigan J.D. Bogner J.A. Latent factors in measures of rehabilitation outcomes after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2004;19:445–458. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dijkers M.P. Quality of life after traumatic brain injury: a review of research approaches and findings. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;85:S21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.08.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown M. Gordon W.A. Haddad L. Models for predicting subjective quality of life in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2000;14:5–19. doi: 10.1080/026990500120899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mailhan L. Azouvi P. Dazord A. Life satisfaction and disability after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2005;19:227–238. doi: 10.1080/02699050410001720149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steadman– Pare D. Colantonio A. Ratcliff G. Chase S. Vernich L. Factors associated with perceived quality of life many years after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2001;16:330–342. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Underhill A.T. Lobello S.G. Stroud T.P. Terry K.S. Devivo M.J. Fine P.R. Depression and life satisfaction in patients with traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal study. Brain Inj. 2003;17:973–982. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000110418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teasdale G. Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet. 1974;ii:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Temkin N.R. Dikmen S.S. Anderson G.D. Wilensky A.J. Holmes M.D. Cohen W. Newell D.W. Nelson P. Awan A. Winn H.R. Valproate therapy for prevention of posttraumatic seizures: a randomized trial. J. Neurosurg. 1999;91:593–600. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.4.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dikmen S. Machamer J.E. Winn H.R. Anderson G.D. Temkin N.R. Neuropsychological effects of valproate in traumatic brain injury: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2000;54:895–902. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temkin N.R. Anderson G.D. Winn H.R. Ellenbogen R.G. Britz G.W. Schuster J. Lucas T. Newell D.W. Mansfield P.N. Machamer J.E. Barber J. Dikmen S.S. Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection after traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:29–38. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson J.T. Pettigrew L.E. Teasdale G.M. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J. Neurotrauma. 1998;15:573–585. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennett B. Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;i:480–484. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dikmen S.S. Machamer J. Miller B. Doctor J. Temkin N. Functional status examination: a new instrument for assessing outcome in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:127–140. doi: 10.1089/08977150150502578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick D.L. Danis M. Southerland L.I. Hong G. Quality of life following intensive care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1988;3:218–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02596335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergner M. Bobbitt R.A. Pollard W.E. Martin D.P. Gilson B.S. The Sickness Impact Profile: validation of a health status measure. Med. Care. 1976;14:57–67. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dikmen S.S. Machamer J.E. Powell J.M. Temkin N.R. Outcome 3 to 5 years after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003;84:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell K.R. Temkin N.R. Esselman P.C. Doctor J.N. Bombardier C.H. Fraser R.T. Hoffman J.M. Powell J.M. Dikmen S. The effect of a scheduled telephone intervention on outcome after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005;86:851–856. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dikmen S. Ross B.L. Machamer J.E. Temkin N.R. One year psychosocial outcome in head injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1995;1:67–77. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagulayan K.F. Temkin N.R. Machamer J.E. Dikmen S.S. The measurement and magnitude of awareness difficulties after traumatic brain injury: a longitudinal study. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2007;13:561–570. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dikmen S.S. Temkin N.R. Machamer J.E. Holubkov A.L. Fraser R.T. Winn H.R. Employment following traumatic head injuries. Arch. Neurol. 1994;51:177–186. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540140087018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doctor J.N. Castro J. Temkin N.R. Fraser R.T. Machamer J.E. Dikmen S.S. Workers' risk of unemployment after traumatic brain injury: a normed comparison. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2005;11:747–752. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edna T.H. Cappelen J. Return to work and social adjustment after traumatic head injury. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 1987;85:40–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01402368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oddy M. Humphrey M. Uttley D. Subjective impairment and social recovery after closed head injury. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1978;41:611–616. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.41.7.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dikmen S. McLean A. Temkin N. Neuropsychological and psychosocial consequences of minor head injury. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1986;49:1227–1232. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.11.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dikmen S. Machamer J. Temkin N. Psychosocial outcome in patients with moderate to severe head injury: 2- year follow-up. Brain Inj. 1993;7:113–124. doi: 10.3109/02699059309008165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dikmen S. Machamer J.E. Powell J.M. Temkin N.R. Outcome 3 to 5 years after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003;84:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engberg A.W. Teasdale T.W. Psychosocial outcome following traumatic brain injury in adults: a long-term population-based follow-up. Brain Inj. 2004;18:533–545. doi: 10.1080/02699050310001645829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kersel D.A. Marsh N.V. Havill J.H. Sleigh J.W. Psychosocial functioning during the year following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2001;15:683–696. doi: 10.1080/02699050010013662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wise E.K. Mathews–Dalton C. Dikmen S. Temkin N. Machamer J. Bell K. Powell J.M. Impact of traumatic brain injury on participation in leisure activities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010;91:1357–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cicerone K.D. Azulay J. Perceived self-efficacy and life satisfaction after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22:257–266. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000290970.56130.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown M. Vandergoot D. Quality of life for individuals with traumatic brain injury: comparison with others living in the community. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13:1–23. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199808000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Neill J. Hibbard M.R. Brown M. Jaffe M. Sliwinski M. Vandergoot D. Weiss M.J. The effect of employment on quality of life and community integration after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13:68–79. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherer M. Boake C. Levin E. Silver B.V. Ringholz G. High W.M., Jr. Characteristics of impaired awareness after traumatic brain injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1998;4:380–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Draper K. Ponsford J. Long-term outcome following traumatic brain injury: a comparison of subjective reports by those injured and their relatives. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2009;19:645–661. doi: 10.1080/17405620802613935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lange R.T. Iverson G.L. Rose A. Post-concussion symptom reporting and the “good-old-days” bias following mild traumatic brain injury. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2010;25:442–450. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherer M. Hart T. Whyte J. Nick T.G. Yablon S.A. Neuroanatomic basis of impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: findings from early computed tomography. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:287–300. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spikman J.M. van der Naalt J. Indices of impaired self-awareness in traumatic brain injury patients with focal frontal lesions and executive deficits: implications for outcome measurement. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1195–1202. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]