Abstract

Background. Amphotericin B (AmB), the most effective drug against leishmaniasis, has serious toxicity. As Leishmania species are obligate intracellular parasites of antigen presenting cells (APC), an immunopotentiating APC-specific AmB nanocarrier would be ideally suited to reduce the drug dosage and regimen requirements in leishmaniasis treatment. Here, we report a nanocarrier that results in effective treatment shortening of cutaneous leishmaniasis in a mouse model, while also enhancing L. major specific T-cell immune responses in the infected host.

Methods. We used a Pan-DR-binding epitope (PADRE)-derivatized-dendrimer (PDD), complexed with liposomal amphotericin B (LAmB) in an L. major mouse model and analyzed the therapeutic efficacy of low-dose PDD/LAmB vs full dose LAmB.

Results. PDD was shown to escort LAmB to APCs in vivo, enhanced the drug efficacy by 83% and drug APC targeting by 10-fold and significantly reduced parasite burden and toxicity. Fortuitously, the PDD immunopotentiating effect significantly enhanced parasite-specific T-cell responses in immunocompetent infected mice.

Conclusions. PDD reduced the effective dose and toxicity of LAmB and resulted in elicitation of strong parasite specific T-cell responses. A reduced effective therapeutic dose was achieved by selective LAmB delivery to APC, bypassing bystander cells, reducing toxicity and inducing antiparasite immunity.

Keywords: immunochemotherapy, nanocarrier, adoptive immunity, intracellular, obligate intracellular parasites, leishmaniasis, vaccine

Amphotericin B is an effective antifungal and antiparasitic drug and is the first line of therapy for leishmaniasis [1, 2]. However, it has substantial toxicity including nephrotoxicity and infusion-related reactions, such as fever, chills, hypoxia, hypotension, and hypertension [3]. Currently LAmB is the most effective anti-Leishmania drug and is administered by intravenous infusion [2]. However, LAmB limitations include, (i) LAmB is less effective for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis than it is for visceral leishmaniasis (VL) [1, 4], (ii) LAmB is most effective against Indian VL and less effective in other endemic areas [1], (iii) Side effects and resulting hospitalization pose significant compliance problems, and (iv) the cost of LAmB for a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved regimen is high (approximately $5000 per person) [1]. For VL therapy patients receive 7 LAmB infusions (given over 2 hours) during a lengthy 21-day period, and patients also receive oral antipyretic and antihistamine to reduce LAmB infusion-mediated fever and/or rigors [1, 5]. Furthermore, the treatment often followed by a 1-L saline infusion to reduce potential nephrotoxicity along with antipyretics and/or antihistamines to manage infusion-associated fever and/or rigors [3]. It has been reported that acute LAmB infusion-related reactions occurred in 25% of patients, and mild renal toxicity occurred in 45% of patients [6]. Reducing the effective therapeutic dose could be achieved if LAmB were selectively targeted to infected cells, bypassing cell types that are not infected [7].

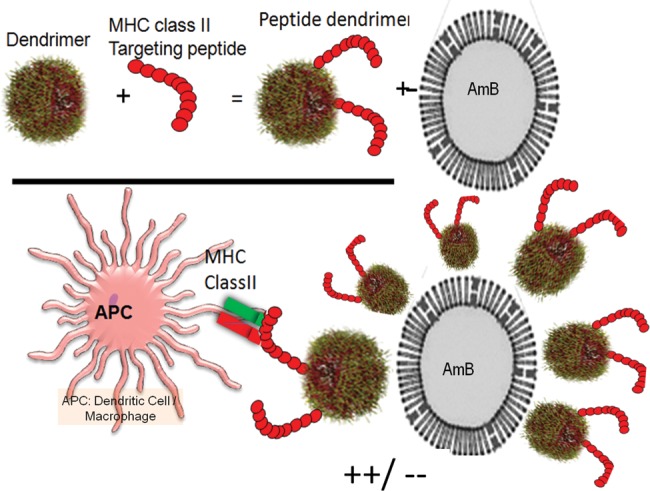

Here, we describe a novel use of a peptide-dendrimer nanocarrier that has been shown to target major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) expressed on human and mouse antigen presenting cells (APCs; eg, macrophages, and dendritic cells [DCs]) [8]. The platform uses a Pan-DR-binding epitope (PADRE) as its APC homing moiety. PADRE is a promiscuous CD4+ Th determinant that binds to most murine and human MHC II molecules [8, 9] and has been previously used as an adjuvant to enhance immune system responses in many studies, including human trials [10–14]. Targeting APCs is a novel use of universal T helper epitopes such as PADRE. PADRE-derivatized dendrimers (PDD) have resulted in effective targeting of DNA to APCs for gene-based vaccination [8]. Because Leishmania are obligate intracellular parasites, T-cell responses and Th1 cell-mediated immunity are required for control of the infection and CD4+ Th1 cells, in particular, are indispensable for resistance [15]. Therefore, we reasoned that PDD, a nanocarrier that targets APCs and elicits a Th1 response, should be able to carry LAmB to the source of infection (macrophages) while also enhancing Th1 adaptive immune responses.

The nanocarrier reported here is a generation 5 Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer coupled to PADRE (PADRE-dendrimer or PDD1). We also designed an alternative T helper epitope-dendrimer platform specific for BALB/c mice where we conjugated a T helper epitope of influenza virus haemagglutinin (HA) molecule (PDD2). Both platforms are positively charged and can bind drugs with a negative net charge and protect them from degradation [8, 16]. Although PDD2 only binds to APCs bearing the H-2d haplotype (BALB/c), PDD1 can bind to MHC II on APCs of both human and mice. Additionally, because CD4+ T cells play a vital role in the generation of CD8+ T cells as well as humoral immune responses, we hypothesized that the intrinsic adjuvant activity of PDD drug delivery may induce anti-leishmania adaptive immunity in a therapeutic setting where leishmanial antigens are produced at the site of infection (Figure 1). Therefore, in an infected host, PDD1 or PDD2 may convert infection to a therapeutic vaccine by inducing an immune response in APCs at the site of infection.

Figure 1.

Cartoon depicts a nanoparticle platform that targets cells expressing MHC class II (APCs). Macrophages and DCs express MHC class II and are the reservoir for Leishmania parasites. PDD is composed of a cell recognition peptide that activates TH cells and PAMAM dendrimer and is a nano carrier platform for drug delivery: MHC class II targeting peptides are covalently linked to the dendrimer, the platform complexes with the cargo and target the MHC class II+ phagocytes/DCs in vivo. Abbreviations: APC, antigen presenting cell; DC, dendritic cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; PAMAM, Polyamidoamine; PDD, PADRE-derivatized dendrimers; TH, T helper.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Conjugation of Peptides to Dendrimers and Characterization of Products

The following peptides (21st Century Biochemicals, Inc.) were used: Pan-HLA-DR-binding epitope (PADRE): aKXVAAWTLKAAaZC; influenza Hemoagglutinin-derived HA110-120: SFERFEIFPKEC (HA), which is a H2-I-Ed-restricted peptide that can be used in BALB/c. A third peptide, made of randomly scrambled amino acids, was used for a control nanoparticle (random peptide-control-dendrimer or selective catalytic reduction dendrimer [ScrDR]). Peptide-dendrimer conjugates were made and characterized as described elsewhere [8] (see Supplementary Figure 1 and method section).

PDD/LAmB or PDD/LAmB-Rhodamin Complexation

See Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure 2A.

Dynamic Light Scattering Analysis

Nanoparticles were detected using a Malvern Zetasizer Nanaoseries dynamic light scattering/molecular sizing instrument with an argon laser (Nano ZS90). The instrument was operated with general-purpose resolution. For size determination, water was selected as a dispersant. All the samples were allowed to equilibrate for 5 seconds before data acquisition. Single measurements with 20 acquisitions were carried out. LAmB complexed with either PDD1 or PDD2 was prepared in water or normal saline. Sizes were analyzed after 20 minutes incubation at room temperature using the Malvern Zetasizer Nanaoseries dynamic light scattering/molecular sizing instrument with argon laser wavelength λ = 830 nm, detector angle 90°. Light scattering experiments were conducted using at least 20 independent readings 10 seconds in duration. The plotted data represent an average of 6 dynamic light scattering (DLS) runs.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Preparations were made of the nanoparticle, the nanoparticle and AmB, and the complex added to the population of cells. Each was preserved in a 2% formaldehyde solution and diluted 1:10 in distilled water. A drop of each sample was placed on a carbon and nitrocellulose coated 200 mesh copper grid and allowed to air dry. The grids were then examined at magnifications up to 245 000 × in a Philips CM-10 transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Images were taken of each preparation using a Gatan digital camera.

Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity was performed on Hep2 cells and evaluated using the MTT assay (see the details of MTT assays in the Supplementary Methods).

Assessment of Cell Specific Targeting and Cellular Internalization

In vivo macrophage uptake of LAmB-Rh and complexes of PDD (PDD1 or PDD2)/LAmB-Rh at specified ratios were also evaluated. After receiving intraperitoneal injections of either of LAmB-Rh or PDD/LAmB-Rh, mice were killed, and macrophages from the peritoneal cavity were collected as described in the materials and methods. Murine peritoneal macrophages were either resident or induced as described. Flow cytometry and confocal florescent microscopy experiments were conducted to analyze the binding of complexes to cells. A confocal microscope was used to examine the fluorescence distribution by z-sections.

Elicitation and Collection of Peritoneal Macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages were elicited as follows: 8 week old wild type BALB/c or C57BL female mice were given 1.5 mL of sterile 3% thioglycollate via intraperitoneal injection and killed by CO2 at day 4 of injection. LAmB-Rh ± PDD or ScrDR treatments were administered to these mice via intraperitoneal injection during the last 2 hours of the 4-day elicitation period (see the details of macrophage isolation in the Supplementary Methods).

Mice and Inoculation of Leishmania major

For in vivo experiments, 1 × 106 metacyclic promastigotes were injected intradermally in the dorsum one inch in front of the base of the tail of mice. Treatment was started once the lesions were between 20–70 mm2 in size and was administered once a day for 10 days intraperitoneally. The positive control was LAmB administered at 37.5 mg/kg/day for 10 days. The animals were examined daily, and clinical signs of disease were noted. Once a lesion formed, its size was monitored by measuring its 2 widest diameters at weekly intervals for 4 weeks. Lesion sizes were compared to mice infected but not treated. Moribund or sick animals were killed as described in the University of Miami IACUC approved protocol. All mouse studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University Of Miami Miller School Of Medicine, and all animals were housed in American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved facilities (see the details in the Supplementary Methods).

Interferon γ Enzyme-linked Immusorbent Assay

Owing to the ability of universal T helper to bind MHC class II, we have recently [8], used a nanoparticle platform for targeted transfection of mouse APC cells with nucleic acid resulting in the expression of native form of the antigen. Here, the APC targeting moiety is an I-Ed MHC class II epitope (H-2-IEd), SFERFEIFPKEC, or HA, that specifically binds BALB/c MHC class II, expressed on BALB/c APCs. The HA-dendrimer (HADR) complexes DNA and escorts it into APC. This method creates a novel T cell immunomonitoring platform that features the use of HADR/DNA (eg, plasmid DNA encoding for L major antigens) to generate APC expressing L. major specific epitopes for presentation to T cells, all in the same well. Therefore, to assess the antigen specific T cell responses in treated mice, we employed HADR complexed with a mixture of four DNA plasmids harboring L. major antigens (KMPII, TRYP, LACK and PAPLE22).

Mice, 5 per group, with L. major lesions received intraperitoneal injections of PDD/LAmB (low-dose), ScrDR/LAmB (low-dose), or L-AmB (full-dose) for 10 days. Splenocytes from individual mice was isolated, washed with RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% FCS and penicillin, and placed at 1 × 106 cells/well in 96-well tissue culture plates. Splenocytes from treated animals were stimulated with HADR (40 µg) complexed with a set of plasmids (4 µg) that encode for L. major antigens. HADR (40 µg) complexed with empty pVAV (4 µg) was used as a “background” in parallel wells for each test. Interferon γ (IFN-γ) measurements in the splenocyte culture supernatants were performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, MN) after plates were incubated at 37°C 5% CO2 for 48 hours. IFN-γ “background” measurements were subtracted from all data. Secreted IFN-γ upon stimulation with HADR/ L major plasmids was measured using ELISA reagents. The control plasmid (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and pVAX with inserted L. major 4 antigens genes (provided by Professor Jordi Alberola Domingo, LeishLAB Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Spain) were used in this study. In brief, after 40 µg of HADR was mixed with the 4 L. major encoding plasmids (total of 4 µg, 1 µg of each plasmid) or with the control plasmid (empty vector, 4 µg), the tubes were left at room temperature for 20 minutes to form the complex. All HADR/plasmid complexes were made in saline. Splenocytes were co-cultured with HADR/DNA complexes, and IFN-γ ELISA was performed on the supernatants of the cultures 48 hours post-stimulation.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification

Leishmania DNA in tissue samples was detected by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as described elsewhere [17]. Briefly, the forward primer, reverse primer and the Taq-Man MGB probe were designed to target conserved DNA regions of the kinetoplast minicircle DNA from Leishmania sp. Eukaryotic 18SRNAPre-Developed TaqMan Assay Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used as an internal reference. Each amplification was performed in triplicate in a 25 µL reaction volume (TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix; Applied Biosystems). The thermal cycling profile was 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, followed by 60°C for 1 minute. Leishmania DNA load in each sample was determined by relative quantification using the 2−ΔΔCt method [18, 19]. Results are expressed as x-fold more DNA copies than the calibrator sample. The calibrator was a spiked sample with a known number of parasites [19].

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) between groups was performed after normality evaluation by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Pairwise post hoc analysis was performed using the Holm-Sidak test or the Dunn test. ANOVA on Ranks was used if the sample was not normally distributed. The Student T test was used to compare 2 groups. Kaplan Meier log-rank followed by the Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis was used to evaluate differences in survival between groups.

RESULT

PDD/LAmB Complex Characterizations

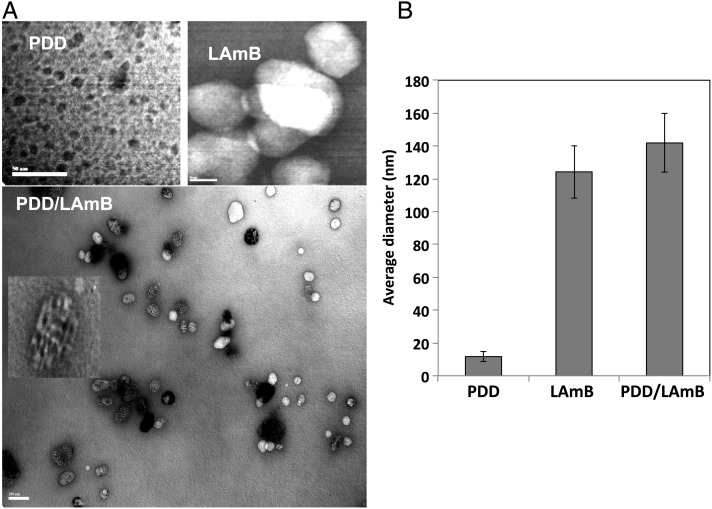

The synthesis and chemical characterization of PDD was described elsewhere [8]. PDD, positively charged, and LAmB, negatively charged, complex readily in solution. PDD-LAmB complex formation was confirmed using TEM and DLS analysis (Figure 2A and 2B). The size of the PDD, LAmB, and PDD/LAmB complexes were analyzed by TEM and DLS. It was observed that the PDD sample was approximately 11.7 nm (99.9%) in diameter while LAmB to be 124.2 nm in size. The electrostatic assembly of the 2 resulted in the PDD-LAmB complex of size 141.8 nm. The expected size of the complex (approximately 147.6 nm) and the DLS data matched closely confirming stable PDD/LAmB complex formation. Similarly, results obtained by DLS are corroborated by TEM micrographs. A ratio of 1:10 (LAmB:PDD) was used in these studies based on our previous work [8]. This ratio has resulted in efficient shuttling of the cargo and is associated with strong nontoxic immunopotentiating activity [8]. The TEM clearly shows that LAmB is decorated with multiple PDD molecules (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

PDD/LAmB complexation characterizations. A, TEM image of a PDD/LAmB complex. Multiple PDD particles complex with a LAmB. B, Average diameters of PDD, LAmB, or PDD/LAmB complexes using DLS. Abbreviations: DLS, dynamic light scattering; LAmB, liposomal amphotericin B; PDD, PADRE-derivatized dendrimers; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Nontoxic In Vivo Macrophage Targeting

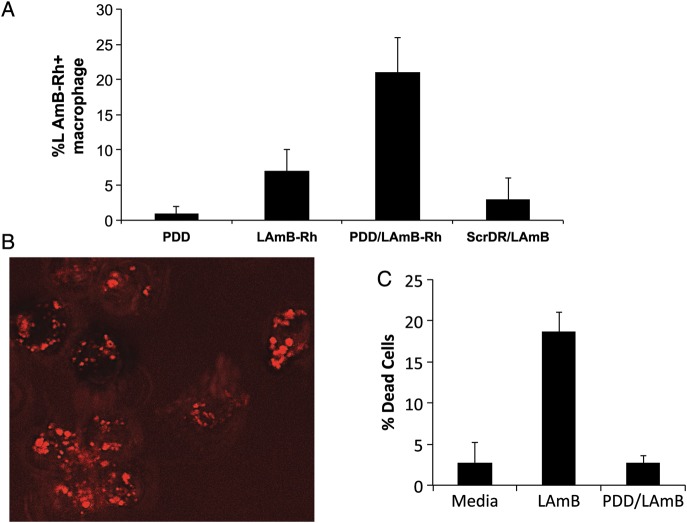

Next, LAmB was labeled with Rhodamin B, a positively charged fluorochrome (Supplementary Figure 2A), and the product (LAmB-Rh) was complexed with PDD at a weight ratio of 1:10 (LAmB-Rh:PDD). PDD-LAmB and PDD-LAmB-Rh were injected intraperitoneally into MAFIA C57BL/6 mice that express GFP only in macrophages. Control mice received LAmB alone or LAmB complexed with PAMAM-dendrimer coupled to a random untargeted peptide (ScrDD-LAmB). Peritoneal fluid was aspirated 1 hour after intraperitoneal injection, and cells were washed and analyzed by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that the percentage of macrophages positive for Rhodamin B was significantly greater in mice treated with PDD-LAmB-Rh than those that received either Rh-LAmB or ScrDR-Rh-LAmB (Figure 3A). In vivo macrophage targeting by PDD/LAmB-Rh (30% ± 5%) was significantly higher (P < .001) than that of LAmB-Rh (7.0% ± 3.7%). Furthermore, macrophages examined with a confocal microscope, using 0.5 μm slices, revealed that within 1 hour, PDD/LAmB-Rh was in the cell (Figure 3B). The in vitro toxicity of LAmB and PDD/LAmB on HEPG2 cells was also extensively analyzed. As shown in Figure 3C, PDD significantly reduced LAmB toxicity. PDD reduces LAmB toxicity via dose reduction and reducing off-targeting.

Figure 3.

PDD/LAmB in vivo APC targeting and effect on LAmB toxicity. A, Summary of the flow cytometry analysis of isolated resident peritoneal macrophages upon interaperitoneal injections of LAmB-Rh, PDD/LAmB-Rh, or controls. In vivo macrophage targeting assessed by flow cytometry analysis showed that percentage of macrophages positive for Rh delivered by PDD/LAmB-Rh is significantly (P < .001) higher (%30 ± 5%) than that delivered by LAmB-Rh or by ScrDR/LAmB (%7 ± 3.7%). B, Confocal image of the peritoneal macrophages (Z-6 of a series of 20 fluorescence images where Z was 1 μm) demonstrating that the LAmB-Rh is up-taken by macrophage. C, In vitro toxicity of LAmB and PDD/L-AmB on HepG2 cells. LAmB with and without PDD was added at 1 μm per mL of HepG2 cells in the culture and MTT assay was performed as it is discussed in the materials and methods. The average percentages of dead cells of 3 separate experiments are shown. LAmB cell toxicity on HepG2 cells was reversed by PDD (P < .007). Abbreviations: APC, antigen presenting cell; LAmB, liposomal amphotericin B; PDD, PADRE-derivatized dendrimers; ScrDR, selective catalytic reduction dendrimer.

Efficacy in Animal Model

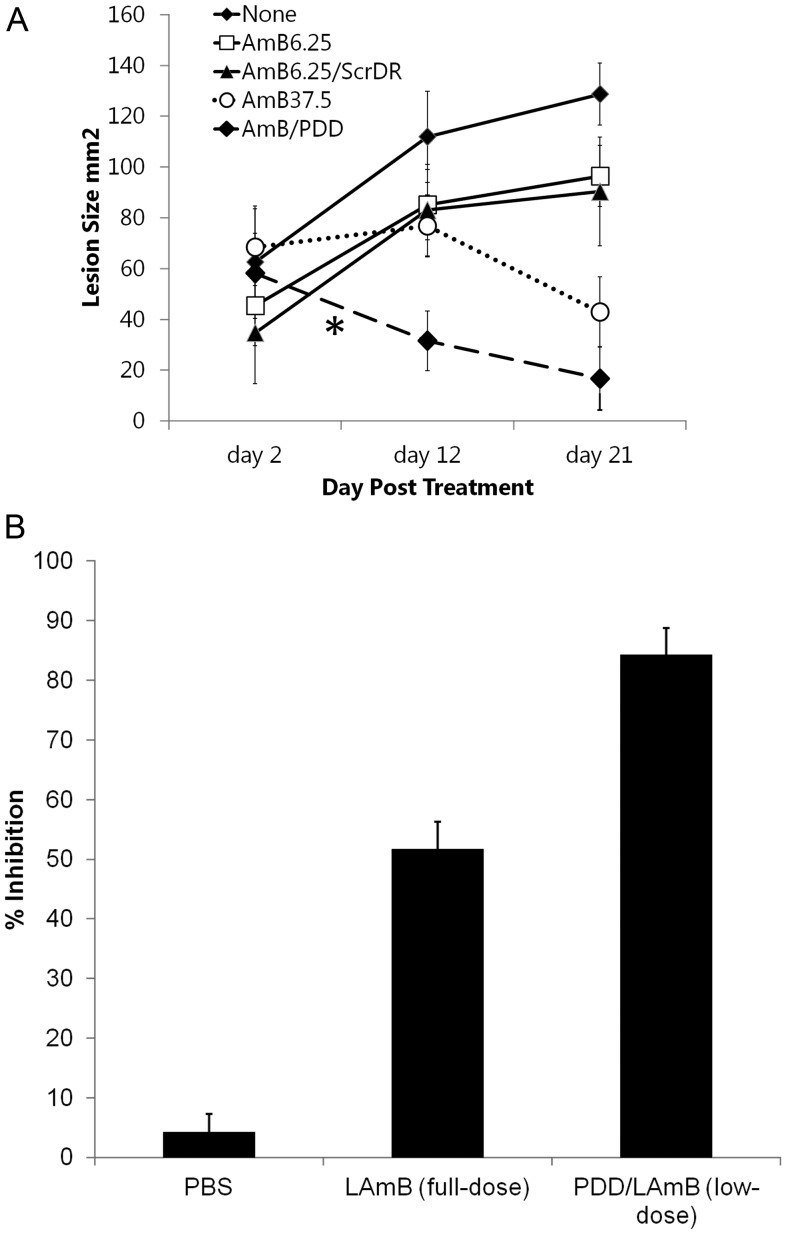

PDD-LAmB and the controls described above were then used in a mouse model of therapy for cutaneous L. major infection. Female BALB/c mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 1 × 106 metacyclic promatigotes of L. major (clone VI; MHOM/IL/80/Friedlin). Treatment was started once the lesions reached a surface area between 20 and 70 mm2. Mice received intravenous injections of LAmB (37.5 mg/kg/day, the full dose), LAmB (6.25 mg/kg/day low-dose), PDD-LAmB (6.25 mg/kg/day low-dose with PDD, or 16.7% of full dose), or ScrDR-LAmB (6.25 mg/kg/day or 16.7% of full dose) once a day for 10 consecutive days. Figure 4A shows that therapy with PDD/LAmB at low dose was as effective as that of LAmB at full dose. The skin lesions of the 2 groups were of comparable size despite different LAmB dosing (Figure 4A). This finding demonstrates that PDD conjugated with LAmB enhanced the efficacy of LAmB treatment by at least 6-fold (Figure 4A), which is consistent with increased in vivo targeting of macrophages in the peritoneal cavity (Figure 3A). PDD-LAmB treatment resulted in the closure of skin lesions in 100% of the treated mice (Figure 4A). The observation that the low-dose LAmB with untargeted nanoparticle (ScrDD-LAmB) treatment has no treatment effect strongly suggests that PDD is required for increased drug efficacy and lowering the required dose of LAmB presumably by targeting LAmB to macrophages. In addition, the kinetics of the closure of skin lesions clearly demonstrated that PDD conjugation accelerated the therapeutic effects of LAmB (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 3). Although the full-dose of LAmB required >12 days to reduce the size of skin lesions, treatment with PDD-LAmB complex containing only 16.7% of the LAmB dose led to a remarkable improvement in skin lesions after only a few days of treatment (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 3). Interestingly, real-time PCR amplification and analysis of the parasite burden [17], in the spleen showed that mice treated with PDD-LAmB had a significantly lower (P < .005) parasite burden than those treated with LAmB (Figure 4B) representing a approximately 86% reduction in the parasite burden.

Figure 4.

PDD lowers LAmB effective dose and accelerates its efficacy. A, Effects of different doses and formulation of LAmB on cutaneous leishmaniasis as assessed by lesion area. Mice bearing cutaneous Leishmania major lesions of similar size received either the full-dose LAmB, or LAmB at a low dose (6.25 mg/k/day) either alone, encapsulated, in a control nanoparticle (ScrDR), or in PDD1. The therapeutic effects of PDD1/LAmB low dose (6.25 mg/k/day for 10 days) is accelerated (*) when compared to that of full dose (37.5 mg/k/day for 10 days, dotted line). B, Similar data were achieved using PDD2 engrafted LAmB showing a significantly faster effect on reducing lesion areas. Panel B shows the quantitative parasite burden in spleen 12 days after treatments. QPCR was performed on the DNA obtained from known amounts of the spleen samples of mice that have been treated with either LAmB (full dose), PDD/LAmB (low dose) or the PBS treated group. The data are shown as the percentage of the inhibition of parasite burden in spleens of mice. Abbreviations: LAmB, liposomal amphotericin B; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PDD, PADRE-derivatized dendrimers; QPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; ScrDR, selective catalytic reduction dendrimer.

PDD-LAmB Complex Enhanced Immune Responses to L. major Infection

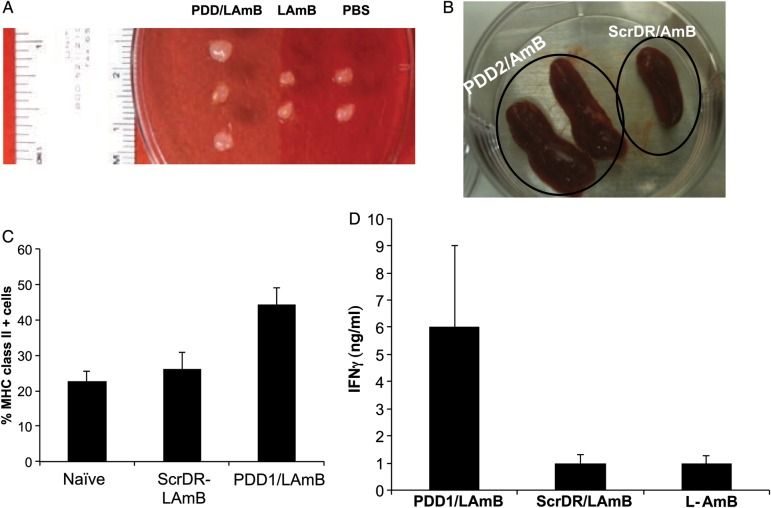

When compared with LAmB treatment, PDD-LAmB therapy resulted in the enlargement of the draining lymph node (Figure 5A). Moreover, the spleen of PDD-LAmB treated mice was markedly larger than that of mice treated with ScrDR-LAmB (Figure 5B). Potent immunotherapies or adjuvanted vaccinations are known to result in transient spleen and lymph node enlargement in mice, which is associated with a Th1 type response [20–22]. In addition, MHC II expression in cells isolated from the dorsal area lymph nodes proximal to the skin lesion was statistically greater in mice treated with PDD-LAmB than in mice treated with LAmB and ScrDR-LAmB (Figure 5C, P < .002). Finally, splenocytes of the mice treated with full-dose LAmB or those that received low-dose LAmB (1/6th of the full dose) complexed either with ScrDR (control nanoparticle), or with PDD were isolated 12 days post treatments. These splenocytes were then co-cultured with a complex composed of HADR and L. major gene expressing plasmids (or HADR/empty pVAX) followed by measurement of IFN-γ in the supernatants of the splenocytes after 48 hours incubation. By selectively transfecting the APCs in the splenocyte culture, this novel T-cell immunomonitoring method allows measurement of antigen-specific T-cell responses. This in vitro transfection method uses the complete peptide repertoire of selected L. major proteins as the source of antigen, allowing the detection of immune reaction against both known and unknown L. major epitopes. Figure 5D shows that PDD-LAmB treatment led to a substantial enhancement of L. major-specific IFN-γ induction from antigen stimulated splenocytes as compared with full-dose LAmB (P < .0001) or control (P < .0002).

Figure 5.

PDD immunopotentiating effects in infected host. A and B, Transient lymphoadenopathy (enlargement of draining lymph nodes and spleen) of infected mice receiving PDD/LAmB vs controls. C, Increased MHC class II expression in the cells of draining lymph node of infected mice treated with PDD/LAmB as compared with control treatments. D, Mice with Leishmania major lesions received intraperitoneal treatments of PDD/LAmB (low dose), ScrDR/LAmB (low dose), or L-AmB (full dose) for 10 days. Splenocytes of individual mice were isolated and placed at 1 × 106 cells/well in 96-well tissue culture plates. Splenocytes from treated animals were stimulated with either (a) HADR (40 µg) complexed with a set of plasmids (4 µg) that encode for L. major antigens or (b) HADR (40 µg) complexed with empty pVAX (4 µg), which served as a background and was deducted from the “a” data. IFN-γ measurements in the splenocyte culture supernatants were performed after 48 hours of incubation at 37°C in air with 5% CO2, as is described in methods. Therapy with low-dose LAmB significantly enhances antigen specific T-cell induced IFN-γ when compared with full-dose LAmB, in infected host (P < .001). Abbreviations: HADR, HA-dendrimer; IFN-γ, interferon γ; LAmB, liposomal amphotericin B; PDD, PADRE-derivatized dendrimers.

Following MHC II binding to endogenous peptides, peptide-MHC II complexes are transported to the cell surface, where peptides are presented to CD4+ T cells. Leishmania sp. inhibits antigen presentation by interfering with the MHC II up-regulation of MHC II molecules. Thus, increased MHC II expression and expansion of CD4+ T cells has been explored as a therapeutic approach in the treatment of leishmaniasis. Here, we showed that PDD-mediated enhancement of MHC II expression and CD4+ T-cell stimulation is associated with elicitation of parasite-specific T-cell responses. Indeed, T helper 2 responses, macrophage-mediated immune suppression, and defects in antigen presentation are underlying mechanisms that are used to evade the immune system in leishmaniasis, resulting in increased parasite burden in tissues such as the spleen [23]. The immunoenhancing effects of PDD, in particular in L. major infected cells, were shown to induce (i) lymphoadenopathy and dendritic cell expansion and trafficking (Figure 5A,and 5B), (ii) enhanced MHC II expression in cells in the draining lymph node (Figure 5C), which indicates cell activation and increased antigen presentation, and (iii) most importantly, the elevation of parasite-specific T-cell responses (Figure 5D).

DISCUSSION

The ability of Leishmania sp. to survive and multiply within DCs and macrophages has made this pathogen an ideal model to study obligate intracellular microbes, which have a major negative impact on public health (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, Toxoplasma gondii, Trypanosoma cruzi, and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]). A nontoxic immunoenhancing nanocarrier that targets APC therefore becomes appealing for the direct targeting of chemotherapeutics to infected cells. By reducing off-targeting effects, PDD, a drug-carrying APC-targeting nanocarrier (Figure 2A, 2B, and 3A, 3B) results in a lower effective dose (Figure 4 A), a more rapid clinical outcome (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 3), reduced LAmB toxicity (Figure 3C), and a lowered (86%) parasite burden in host (Figure 4B), which collectively provided a therapy that enhances patient compliance and lowers cost. In addition, to survive in the intracellular space of host cells, Leishmania species evade the immune system through impairment of DC activation and maturation [24]. For example, Leishmania infection of mice down-regulates MHC class II and costimulatory molecules eliciting a Th2-like profile where the responses to exogenous pathway is preserved [24]. Indeed, increasing MHC class II expression in APCs is a surrogate of enhanced intracellular/endogenous antigen presentation [25]. It has also been shown that amastigotes are able to infect macrophages and DCs without increasing surface expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules, resulting in improper activation and a Th2 response [26–28]. This critical role of MHC class II dysfunction creates an opportunity to develop a nanocarrier that increases MHC class II expression (Figure 5C) and mounts a Th1-like pathogen specific immune response (Figure 5D). Collectively, the LAmB/PDD nanosystem not only lowers the effective drug dose and toxicity, it also activates APC to commit to a Th1 response leading to an effective adoptive immune response against this intracellular pathogen.

Ideal therapies for obligate intracellular pathogens (including leishmaniasis and tuberculosis) should offer high cure rates, reduced treatment dose/duration, improved compliance, reduced toxicity, and reduced chances of unfavorable interactions with antiretroviral treatment for concomitant HIV infection. The PDD/LAmB therapy we describe offers these advantages. Our data demonstrate a high cure rate and reduced treatment dose that can be further optimized for shorter treatments, which in theory should result in improved compliance. PDD/LAmB was also shown to reduce toxicity not only by dose reduction but also by reducing off targeting and perhaps other mechanisms. As shown in the in vitro toxicity (Figure 3B), complexation of LAmB to PDD eliminates the toxicity of LAmB on Hep2 cells. The data presented here provide evidence that PDD reduces the effective LAmB dose by approximately 80% while also showing faster efficacy and lower toxicity. PDD binds LAmB and escorts it selectively to parasite reservoir cells (phagocytes) while its intrinsic CD4+ T helper universal peptide provides “HELP” for the host adaptive immunity resulting in dramatic increased L. major antigen-specific T-cell responses. The safety and efficacy of a PDD-LAmB complex in the treatment of leishmaniasis in humans awaits clinical trials.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We would like to thank the technical support of Ali Muhammad Saeed, a University of Miami MD/PHD student, Oliver Umland, PhD, Manager of Flow Cytometry Core Facility, Diabetes Research Institute University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and Gabriel Gaidosh, Manager of Confocal Core Facility, Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and Dr Ali Nayer of University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, for valuable comments on the preparation of the article.

Financial support. This work was partially supported by a grant from DOD funding (DAMD 17-03-20021) to A. A. Support for G. W. S. was provided by the Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, which is funded by grant P30AI073961 from the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. P. D., V. L. P., and A. A. are the inventors of a provisional patent owned and filed by the University of Miami. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed

References

- 1.Sundar S, Sinha PK, Rai M, et al. Comparison of short-course multidrug treatment with standard therapy for visceral leishmaniasis in India: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:477–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundar S, Chakravarty J, Agarwal D, Rai M, Murray HW. Single-dose liposomal amphotericin B for visceral leishmaniasis in India. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:504–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray HW. Leishmaniasis in the United States: treatment in 2012. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:434–40. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon M, Pavlotsky F, Leshem E, Ephros M, Trau H, Schwartz E. Liposomal amphotericin B treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania tropica. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:973–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapp C, Imbert P, Darie H, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis contracted in Djibouti and resistant to meglumine antimoniate. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2003;96:209–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wortmann G, Zapor M, Ressner R, et al. Lipsosomal amphotericin B for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:1028–33. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suri SS, Fenniri H, Singh B. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2007;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daftarian P, Kaifer AE, Li W, et al. Peptide-conjugated PAMAM dendrimer as a universal platform for antigen presenting cell targeting and effective DNA-based vaccinations. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7452–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daftarian P, Sharan R, Haq W, et al. Novel conjugates of epitope fusion peptides with CpG-ODN display enhanced immunogenicity and HIV recognition. Vaccine. 2005;23:3453–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Rosa C, Longmate J, Lacey SF, et al. Clinical evaluation of safety and immunogenicity of PADRE-cytomegalovirus (CMV) and tetanus-CMV fusion peptide vaccines with or without PF03512676 adjuvant. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1294–304. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander J, del Guercio MF, Maewal A, et al. Linear PADRE T helper epitope and carbohydrate B cell epitope conjugates induce specific high titer IgG antibody responses. J Immunol. 2000;164:1625–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belot F, Guerreiro C, Baleux F, Mulard LA. Synthesis of two linear PADRE conjugates bearing a deca- or pentadecasaccharide B epitope as potential synthetic vaccines against Shigella flexneri serotype 2a infection. Chemistry. 2005;11:1625–35. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung C-F, Tsai Y-C, He L, Wu TC. DNA vaccines encoding Ii-PADRE generates potent PADRE-specific CD4+ T-cell immune responses and enhances vaccine potency. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1211–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan Y, Yuan S, Xue X, et al. The preventive effect of adjuvant-free administration of TNF-PADRE autovaccine on collagen-II-induced rheumatoid arthritis in mice. Cell Immunol. 2009;258:72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okwor I, Mou Z, Liu D, Uzonna J. Protective immunity and vaccination against cutaneous leishmaniasis. Front Immunol. 2012;3:128. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medina SH, El-Sayed MEH. Dendrimers as carriers for delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Chem Rev. 2009;109:3141–57. doi: 10.1021/cr900174j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Cortes A, Ojeda A, Lopez-Fuertes L, et al. Vaccination with plasmid DNA encoding KMPII, TRYP, LACK and GP63 does not protect dogs against Leishmania infantum experimental challenge. Vaccine. 2007;25:7962–71. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bretagne S, Durand R, Olivi M, et al. Real-time PCR as a new tool for quantifying Leishmania infantum in liver in infected mice. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:828–31. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.4.828-831.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olbrich AR, Schimmer S, Dittmer U. Preinfection treatment of resistant mice with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides renders them susceptible to friend retrovirus-induced leukemia. J Virol. 2003;77:10658–62. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10658-10662.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipford GB, Sparwasser T, Zimmermann S, Heeg K, Wagner H. CpG-DNA-mediated transient lymphadenopathy is associated with a state of Th1 predisposition to antigen-driven responses. J Immunol. 2000;165:1228–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olishevsky S, Shlyakhovenko V, Kozak V, Yanish Y. Response of different organs of immune system of mice upon administration bacterial CpG DNA. Exp Oncol. 2005;27:290–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palatnik-de-Sousa CB. Vaccines for leishmaniasis in the fore coming 25 years. Vaccine. 2008;26:1709–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandonisio O, Spinelli R, Pepe M. Dendritic cells in Leishmania infection. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:1402–9. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das A, Ali N. Vaccine Development against Leishmania donovani. Front Immunol. 2012;3:99. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antoine JC, Jouanne C, Lang T, Prina E, de Chastellier C, Frehel C. Localization of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in phagolysosomes of murine macrophages infected with Leishmania amazonensis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:764–75. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.764-775.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antoine JC, Lang T, Prina E, Courret N, Hellio R. H-2M molecules, like MHC class II molecules, are targeted to parasitophorous vacuoles of Leishmania-infected macrophages and internalized by amastigotes of L. amazonensis and L. mexicana. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 15):2559–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.15.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prina E, Jouanne C, de Souza Lao S, Szabo A, Guillet JG, Antoine JC. Antigen presentation capacity of murine macrophages infected with Leishmania amazonensis amastigotes. J Immunol. 1993;151:2050–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.