Abstract

Patient education and effective communication are core elements of the nursing profession; therefore, awareness of a patient's health literacy is integral to patient care, safety, education, and counseling. Several past studies have suggested that health care providers overestimate their patient's health literacy. In this study, the authors compare inpatient nurses' estimate of their patient's health literacy to the patient's health literacy using Newest Vital Sign as the health literacy measurement. A total of 65 patients and 30 nurses were enrolled in this trial. The results demonstrate that nurses incorrectly identify patients with low health literacy. In addition, overestimates outnumber underestimates 6 to 1. The results reinforce previous evidence that health care providers overestimate a patient's health literacy. The overestimation of a patient's health literacy by nursing personnel may contribute to the widespread problem of poor health outcomes and hospital readmission rates.

Health literacy (HL) is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Ratzan & Parker, 2000). Patients with limited HL are more likely to misunderstand health information (Friedman & Hoffman-Goetz, 2006), have a shorter life expectancy (Baker et al., 2007), and experience 30-day hospital reutilization after discharge (Mitchell, Sadikova, Jack, & Paasche-Orlow, 2012). According to the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy, 36% of Americans have below basic or basic HL (Kutner, Jin, & Paulsen, 2006).

Patient education and effective communication are core elements of the nursing profession; therefore, awareness of a patient's HL is integral to patient care, safety, education, and counseling. In health care organizations, low HL is sometimes assessed by asking patients the questions, “Do you have any limitations to learning?” and “What was the last grade completed?” Previous research has identified that neither of these questions is an accurate assessment of a patient's HL status (Kutner et al., 2006). Macabasco-O'Connell and Fry-Bowers (2011) surveyed 270 nurses; among 76 respondents, 80% reported that they never or rarely assessed HL using a validated tool and 60% responded that they used their gut feeling to estimate a patient's HL level (Macabasco-O'Connell & Fry-Bowers, 2011). There is also evidence that physicians have limited knowledge and skills related to HL assessment. Kelly and Haidet found that physicians (n = 12) incorrectly identified their patient's HL levels 40% of the time and most often overestimated the patient's HL level (Kelly & Haidet, 2007). In another study, investigators found that resident physicians perceived 90% of the patients as not having literacy problems, when, in fact, 36% of the patients had low HL (Bass, Wilson, Griffith, & Barnett, 2002). To our knowledge, there are no studies examining the concordance between a nurse's perceptions of a patient's HL and a patient's measured HL status. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare nurses' estimate of a patient's HL to the patient's HL, as measured using the Newest Vital Sign (NVS). As a secondary activity, we also aimed to determine whether there was a relation between the patient's NVS score and results of the Single Item Literacy Screener (SILS) or the patient's self-reported educational attainment.

Method

This was a cross-sectional study performed using a convenience sample (nurses [n = 30] and patients [n = 65]) recruited from two inpatient cardiac units. Patients and nurses were recruited over a 6-month period. Inclusion criteria included men and women (older than 18 years of age), cardiac-related diagnosis, and ability to read English. Patients were excluded if they had cognitive impairment documented by the admitting health care provider. Patient demographic information (e.g., race/ethnicity, date of birth) was recorded from the medical record. Data about educational attainment were obtained during a patient interview by asking the question, “What was the highest grade of schooling you finished?” The patient was read the following options: 8th grade and below, 9–12th grade without graduation from high school, or graduated from high school. Patients completed the NVS and the SILS. The patient's nurse was then queried to estimate the patient's HL level by selecting one of three questions that reflected the three HL categories of the NVS. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Health Literacy Measurement

The patient's HL was measured using a multi-item tool such as the NVS and a single-item question such as the SILS (Wallace, Rogers, Roskos, Holiday, & Weiss, 2006; Weiss et al., 2005). The patients read the NVS, a nutrition label, and then answered six questions asked by the research assistant. Each question is worth one point. On the basis of their scores, patients were categorized as having adequate health literacy for scoring 4–6 points, possibility of functional health literacy for scoring 2–3 points, and high likelihood of limited health literacy for scoring 0–1 point (Weiss et al., 2005).

A research assistant who was blinded to the patient's reading ability read to the patient the SILS question: “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?” and five possible options, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), from which the patient reported his or her response (Wallace et al., 2006). In this study, if the patient answered not at all, a little bit, or somewhat, he or she was classified as having limited HL. If the patient answered quite a bit or extremely, he or she was classified as having adequate HL. After assessing the patient's HL, the patient's nurse was queried to estimate the patient's HL level by selecting one of three questions that were developed to reflect the three HL categories of the NVS (see Table 1).

Table 1.

NVS scale changed to nurse query

| NVS question | Question to nurse |

|---|---|

| High likelihood of limited literacy | “Does your patient have low health literacy?” |

| Possibility of limited literacy | “Does your patient have marginal health literacy?” |

| Almost always adequate literacy | “Does your patient have adequate health literacy?” |

Note. NVS = Newest Vital Sign.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis included descriptive statistics (patient demographics and HL scales and ratings). The SILS results were categorized as inadequate and adequate with the marginal category added to the inadequate category. The results were dichotomized to address the SILS decreased sensitivity and specificity in assessing patients with marginal HL. Kappa statistics were calculated to measure agreement between the patient's NVS result and the nurse's NVS rating (Cohen, 1960). Spearman's rho was computed to measure the relation between the SILS and NVS scores. Spearman's rho was also used to determine the association between the NVS and the patient's highest educational attainment. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (Version 21, Chicago, IL).

Results

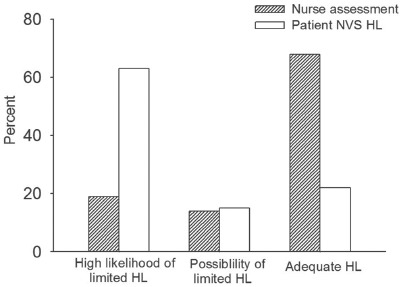

Study patients were mostly female (64.6%), African American (81.5%) and had heart failure as a diagnosis (see Table 2). The mean age of patients was 60 years (SD = 16 years). Educational attainment, insurance status, and admitting diagnosis are noted in Table 1. On the basis of the NVS scores, 63% of patients had a high likelihood of limited HL, whereas nurses reported 19% of patients having a high likelihood of limited HL (see Figure 1). Nurses reported 68% of patient's having adequate HL, overestimating the number of patients who had adequate HL (22%). The kappa coefficient showed a very low level of agreement between the patient's NVS score and the nurse's rating. (κ = 0.09).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | N = 65 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M (SD) | 60 (16) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 42 | 64.6 |

| Male | 23 | 35.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 6 | 9.2 |

| African American | 53 | 81.5 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 6.2 |

| Asian | 2 | 3.1 |

| Education | ||

| 8th grade or below | 7 | 10.8 |

| 9th–12th grade (did not graduate) | 9 | 13.8 |

| Graduated from high school | 49 | 75.4 |

| Health insurance status | ||

| Medicare | 31 | 47.7 |

| Medicaid | 15 | 23.1 |

| Private insurance | 11 | 16.9 |

| Self-pay | 8 | 12.3 |

| Reason for admission | ||

| Heart failure | 33 | 50.8 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 | 9.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 | 1.5 |

| Catheterization/percutaneous coronary intervention | 1 | 1.5 |

| Electrophysiology device | 4 | 6.2 |

| Chest pain | 15 | 23.1 |

| Electrophysiology issues | 4 | 6.2 |

| Other | 1 | 1.5 |

Figure 1.

Nurse assessment and patient NVS results. HL = health literary, NVS = Newest Vital Sign.

Among the patients who reported graduating from high school, 40% had a high likelihood of limited HL (see Table 3). Spearman's rho revealed a small but statistically significant association between the patient's NVS and educational attainment (ρ = 0.392, p < .001). On the basis of SILS scores, 65% of patients had adequate HL and 35% had inadequate. However, on the basis of the NVS scores, the majority of patients had high likelihood of limited HL (Table 4). Spearman's rho also revealed a small but statistically significant relation between the NVS and SILS (ρ = .323, p < .005).

Table 3.

Patient educational attainment stratified by NVS categories

| High likelihoodof limited healthliteracy |

Possibility oflimited healthliteracy |

Adequate health literacy |

Total |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| 8th grade or below | 7 | (10.8) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 7 | (10.8) |

| 9th–12th grade (did not graduate) | 8 | (12.3) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (1.5) | 9 | (13.8) |

| High school graduate or above | 26 | (40.0) | 10 | (15.4) | 13 | (20.0) | 49 | (75.3) |

| Total | 41 | (65) | 10 | (15.4) | 14 | (21.5) | ||

Note. NVS = Newest Vital Sign.

Table 4.

Patient SILS results stratified by NVS categories

| High likelihood of limited health literacy |

Possibility of limited health literacy |

Adequate health literacy |

Total |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| SILS | ||||||||

| Inadequate | 19 | (29.2) | 3 | (4.6) | 1 | (1.5) | 23 | (55) |

| Adequate | 22 | (33.8) | 7 | (10.8) | 13 | (20.0) | 42 | (67) |

| Total | 41 | (66.0) | 10 | (15.4) | 14 | (21.5) | ||

Note. NVS = Newest Vital Sign, SILS = Single Item Literacy Screener.

Discussion

Using the NVS HL screening tool, our results demonstrate that nurses incorrectly identify patients with low HL and in this study, the majority of nurses overestimated the patient's HL. Previous research has identified physicians overestimating patient's HL, but this is the first study to examine nurses assessment of patient's HL. The nurse is the health care professional who is responsible for patient understanding about follow-up appointments, new medications, dietary restrictions, and activity level after discharge. As a result of overestimating the patient's HL, the nurse may be communicating to the patient in such a manner that the patient does not understand the information taught.

This study reinforces the finding that level of educational attainment is related to a patient's HL. Yet, it should be noted in our study the relationship was low (ρ = 0.392). In our study, 75% of patients had graduated from high school, yet 40% of the high school graduates had high likelihood of limited HL. Similarly, the National Assessment of Adult Literacy study reported 11% of adults who graduated from high school has basic or below basic HL. Our study patient population was primarily minorities and the weak relationship between education and the NVS may be explained by cultural or ethnic differences. Nurses and health care organizations have traditionally used educational attainment as a method to assess learning limitations, but our results conclude this method may not be accurate.

In this study, we used the NVS and SILS to assess patient HL. Both tools have been used in patient populations with chronic diseases such as diabetes and arthritis (Hirsh et al., 2011; Kirk et al., 2011). In this sample, the NVS and SILS were weakly associated. This weak relation is not surprising given that the NVS and SILS measure different constructs of HL. In addition, HL is a complicated construct and a tool that measures all aspects of HL has not been established. The NVS assesses complicated cognitive functions including simple math calculations and reading comprehension (Wolf et al., 2012) whereas the SILS is a self reported measure not requiring mental calculations. The SILS and NVS were chosen for this study because other trials have shown these tools as effective in assessing HL when there is limited time. The NVS is a well validated tool that is growing in popularity in both research and clinical settings.

The evidence from this study would suggest that training in HL is needed for inpatient nurses. While some nursing schools now include HL education in their curriculum, most nurses did not receive this education. The 2008 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses estimates 70% of nurses received their initial nursing education greater than 14 years ago, and HL was not a subject offered in nursing curriculum at that time. The same 2008 survey identified 62.2% of nurses as being employed by hospitals (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2010). Other health care professionals should be included in HL training so all professionals impacting the patient experience can be involved. For this to occur, leadership within health care organizations need to make an investment and train their workforce to become health literate (Brach et al., 2012). The Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit is a resource that is available to the general public and it provides a method for systematic evaluation of clinical practices, resources to educate staff and to methods to communicate with patients in a clear and effective manner (DeWalt et al., 2010).

The evidence supporting HL screening has not been established. In their review, Paasche-Orlow and Wolf (2008) found little evidence to support patient HL screening and acknowledged the potential harm to patients from shame and stigma. Furthermore, Seligman and colleagues (2005) conducted a randomized controlled trial examining the effect of notifying physicians of their patient's low HL. Although physicians who received the notification were more likely to use low HL management strategies, the same physicians felt less satisfied with their clinical encounter. There were no differences in the measured patient outcomes (Seligman et al., 2005). As a result, it has not been established whether notifying health care providers of their patient's low HL will affect health care providers teaching strategies or patient outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, the patient and nurse sample came from a two-hospital units, was a small convenience sample, and there was a lack of diversity in race/ethnicity in the patient population. Second, because there is no established HL tool that measures all elements of HL, it should be considered that the three methods used in this study do not measure the same constructs. Last, this study failed to control for nurse's knowledge regarding HL and individual nurse characteristics. Future research should assess the nurses previous knowledge regarding HL and include nurse demographics.

Conclusion

We found that nurses overestimate the HL skills of their patients. This is an important target for professional development as such errors may contribute to the widespread problem of poor health outcomes and hospital readmission rates in patients with low HL. Schools of nursing and health care organizations need to undertake the task of educating their nurses about HL. Future research should be targeted at the nursing profession to mitigate the negative patient outcomes associated with low HL.

References

- Baker D. W., Wolf M. S., Feinglass J., Thompson J. A., Gazmararian J. A., Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1503–1509. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass P. F., 3rd, Wilson J. F., Griffith C. H., Barnett D. R. Residents' ability to identify patients with poor literacy skills. Academic Medicine. 2002;77:1039–1041. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach C., Dreyer B., Schyve P., Hernandez L. M., Baur C., Lemerise A. J., Parker R. Attributes of a health literate organization. Washington, DC: Institiute of Medicine; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/∼/media/Files/PerspectivesFiles/2012/Discussion-Papers/BPH_HLit_Attributes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt D. A., Callahan L. F., Hawk V. H., Broucksou K. A., Hink A., Rudd R., Brach C. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. AHRQ Publication No. 10-0046-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman D. B., Hoffman-Goetz L. A systematic review of readability and comprehension instruments used for print and web-based cancer information. Health Education and Behavior. 2006;33:352–373. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277329. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration. The registered nurse population: Initial findings from the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. Washington, DC: Auth or; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh J. M., Boyle D. J., Collier D. H., Oxenfield A. J., Nash A., Quinzanos I., Caplan L. Limited health literacy is a common finding in a public health hospital's reheumatology clinic and is predictive of disease severity. Journal of Clinical Rheumotology. 2011;17:236–241. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318226a01f. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318226a01f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P. A., Haidet P. Physician overestimation of patient literacy: A potential source of health care disparities. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;66:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.007. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk J. K., Grzywacz J. G., Arcury T. A., Ip E. H., Nguyen H. T., Bell R. A., Quandt S. A. Performance of health literacy tests among older adults with diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27:534–540. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1927-y. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1927-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner M. G. E., Jin Y., Paulsen C. The health literacy of America's adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: National Center of Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Macabasco-O'Connell A., Fry-Bowers E. K. Knowledge and perceptions of health literacy among nursing professionals. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(Suppl. 3):295–307. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604389. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S. E., Sadikova E., Jack B. W., Paasche-Orlow M. K. Health literacy and 30-day postdischarge hospital utilization. Journal of Health Communication. 2012;17(Suppl. 3):325–338. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.715233. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.715233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasche-Orlow M. K., Wolf M. S. Evience does not support clinical screening of literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:100–102. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0447-2. doi: 10.1007/s11606-07-0447-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan S. C., Parker R. M. Introduction. In: Selden C. R., Zorn M., Ratzan S. C., Parker R. M., editors. Current bibliographies in medicine 2000-1: Health literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2000. Retrieved from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/archive//20061214/ppubs/cbm/hliteracy.html#15. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman H. K., Wang F. F., Palacios J. L., Wilson C. C., Daher C., Piette J. D., Schillinger D. Physician notification of their diabetes patients' limited health literacy: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:1001–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00189.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace L. S., Rogers E. S., Roskos S. E., Holiday D. B., Weiss B. D. Brief report: Screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B. D., Mays M. Z., Martz W., Castro K. M., DeWalt D. A., Pignone M. P., Hale F. A. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The Newest Vital Sign. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3:514–522. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. S., Curtis L. M., Wilson E. A., Revelle W., Waite K. R., Smith S. G., Baker D. W. Literacy, cognitive function and health: Results of the LitCog study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27:1300–1307. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2079-4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]