Abstract

Introgression of novel genetic variation into breeding populations is frequently required to facilitate response to new abiotic or biotic pressure. This is particularly true for the introduction of host pathogen resistance in plant breeding. However, the number and genomic location of loci contributed by donor parents are often unknown, complicating efforts to recover desired agronomic phenotypes. We examined allele frequency differentiation in an experimental barley breeding population subject to introgression and subsequent selection for Fusarium head blight resistance. Allele frequency differentiation between the experimental population and the base population identified three primary genomic regions putatively subject to selection for resistance. All three genomic regions have been previously identified by quantitative trait locus (QTL) and association mapping. Based on the degree of identity-by-state relative to donor parents, putative donors of resistance alleles were also identified. The successful application of comparative population genetic approaches in this barley breeding experiment suggests that the approach could be applied to other breeding populations that have undergone defined breeding and selection histories, with the potential to provide valuable information for genetic improvement.

Keywords: disease resistance, introgression, allele frequency, identity-by-state, breeding

Experimental evolution studies have long been valued as a means of gaining insight into the rate and degree of response to selection (Burke and Rose 2009). Recent studies have demonstrated that when combined with single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping or resequencing and comparative population genetic approaches, experimental populations can provide a rapid means of identification of loci responding to selection (Burke et al. 2010; Turner et al. 2011; Orozco-Terwengel et al. 2012). The approaches have been successfully applied to a number of systems, from experimental populations of microbes exposed to high-temperature regimes (Tenaillon et al. 2012) to Drosophila populations selected for longevity (Teotónio et al. 2009; Burke et al. 2010). These studies demonstrate the feasibility of identifying adaptive mutations in experimental populations.

Although plant breeding populations are themselves highly successful long-term experimental evolution studies, there is a long-standing tradition of developing experimental populations to supplement traditional breeding approaches (Harlan and Martini 1929; Suneson 1956; Dudley and Lambert 2004). These experimental populations explore both the potential for local adaptation (Allard et al. 1972) and the genetic basis of response to selection (Clegg et al. 1972; Weir et al. 1972). Experimental plant populations have also been used to test the role of genetic incompatibility in the formation of hybrid species (Rieseberg et al. 1996) and the potential for trait introgression in cultivated species (Lin et al. 1995; Jiang et al. 2000).

Historically, uses of population genetic approaches to identify genetic changes in experimental populations have been limited to a few markers, limiting inference regarding the loci contributing to genetic differentiation to single markers representing large genomic regions (Allard et al. 1972; Rieseberg et al. 1996). Recently, the availability of high-density SNP genotyping or resequencing data has provided the potential to identify precise genomic regions that have been undergoing selection. Strong directional selection has the potential to produce populations with dramatic differentiation in allele frequency, a potential signal of selection (Lewontin and Krakauer 1973), which could be detectable either by SNP genotyping (Teotónio et al. 2009) or by resequencing (Burke et al. 2010; Turner et al. 2011). Patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD) (Sabeti et al. 2002) or changes in patterns of identity-by-state (IBS) (Albrechtsen et al. 2010) can also suggest recent selection.

In the present study, we report a population genetic examination of an experimental barley breeding population developed in response to epidemic levels of the fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of Fusarium head blight (FHB). The prevalence and spread of this pathogen increased in the Midwestern United States in the early 1990s (McMullen et al. 1997) and revealed limited genetic variation for disease resistance among existing barley cultivars and the need to introduce novel variation for resistance into breeding programs. During the 35 years preceding the FHB outbreak, the University of Minnesota barley breeding program made use of relatively closed pedigrees in an advanced cycle breeding scheme (Rasmusson and Phillips 1997) that primarily focused on crosses among elite lines from within the breeding population (Condón et al. 2009). After the outbreak, numerous exotic sources of elite lines with known FHB resistance and reduced deoxynivalenol (DON) mycotoxin (which is produced by the pathogen) concentration were evaluated and introduced as parents in the breeding population to enhance FHB resistance (Smith et al. 2013).

Novel adaptive mutations, including resistance to a pathogen, are likely to be rare in breeding populations, because mutation frequency is dependent on effective population size. Introduction of resistance alleles from standing variation outside the breeding population is the primary mechanism to increase disease resistance (Fetch et al. 2003). We report the genetic effects of introgression from a diverse set of 13 barley lines carrying FHB resistance into an existing breeding population. The immediate goal of this experimental population (hereafter referred to as the Reopened population) is to provide substantial improvement in resistance to FHB infection. The Reopened population was compared with a contemporaneous sample of breeding lines from the primary Minnesota breeding population, never subject to introgression of FHB-resistant parents and maintained under a closed pedigree (hereafter referred to as the Closed population) permitting identification of loci potentially subject to selection for FHB resistance in the Reopened population. We demonstrate that comparative population genetic approaches applied to this experimental population provide a complementary approach to QTL and association mapping methods for identifying loci that underlie important phenotypes.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

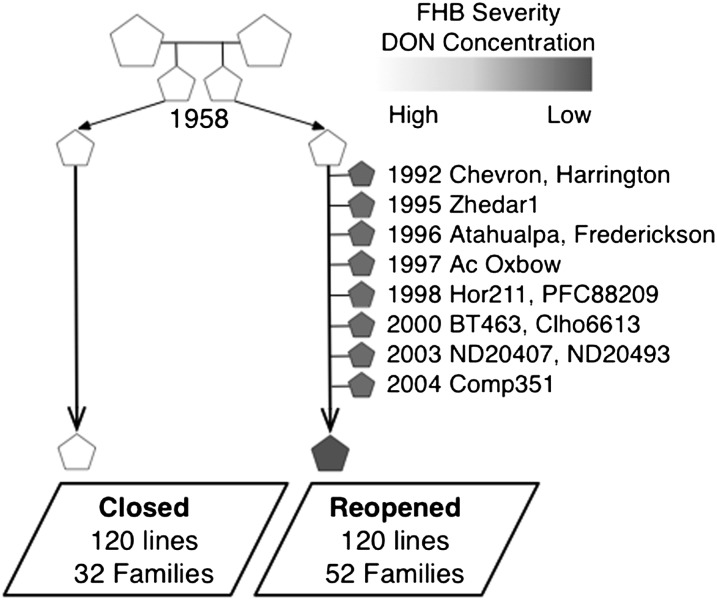

Breeding lines for this study were derived from the six-row malting barley breeding program at the University of Minnesota, which began in the early 1900s. The genetic base of this breeding population is quite narrow, with ∼50% of the six-row germplasm in North America tracing to five ancestors (Martin et al. 1991). In the early 1990s, the original advanced cycle breeding strategy was maintained for part of the breeding program while a new strategy that introduced exotic sources of FHB resistance was implemented in parallel. This resulted in two parallel breeding populations within the breeding program with different breeding histories. To compare these two populations, we created two panels of 120 breeding lines that were representative of the two populations. The Closed panel comprises lines from the advanced cycle breeding program (elite × elite) with a relatively closed pedigree, i.e., few new founders were introduced after 1958 when the strategy was initiated (Condón et al. 2008; Condón et al. 2009). The Reopened panel comprises lines from families derived from the introduction of 13 new donors to the Closed population in response to the FHB epidemic (Figure 1). The lines in each panel were selected from a period of transition between advanced cycle breeding and introduction of disease-resistant parents (2003–2007), such that we could adequately sample both breeding populations. Lines in each panel were selected to maximize the number of families represented within each population; the Closed panel sampled 32 (94%) of 34 families in the Closed population that advanced to preliminary yield trials, and the Reopened panel sampled 52 (87%) of 60 families in the Reopened population. Lines selected for both panels were based on seed or DNA availability, with preference given to lines with malting quality data.

Figure 1.

Breeding history of the Closed and Reopened populations. Filled shapes designate individuals carrying Fusarium head blight (FHB) resistance and/or reduced deoxynivalenol (DON) accumulation. The Reopened population acquired reduced FHB severity and DON concentration through the introgression from 13 donor lines between 1992 and 2004.

The typical development of breeding lines begins with a cross between two parents in the fall followed by self-pollination of the F1 in a greenhouse in the winter. Parents were typically selected after they had been evaluated for 2 years in yield trials based on agronomic performance and acceptable malting quality for the Closed population, and additionally for FHB resistance in the Reopened population. F2 plants were grown in the field and advanced by single-seed descent to the F4 generation without selection. In the second summer after the initial cross, selection was imposed on the F4:5 lines. For the Closed population, F4:5 lines were planted in unreplicated single row plots at a single location and visually selected based on general agronomic traits, including maturity, heading date (flowering time), plant height, stem breakage, lodging, and plump kernels. For the Reopened population, F4:5 lines were planted in single-row plots at two disease nurseries with two replicates and evaluated for FHB disease severity. For lines selected with low levels of disease, harvested grain from each plot was analyzed for DON produced by the pathogen. Further selection was imposed for low DON concentration in the grain. In both the Closed and Reopened populations, ∼10% selection was imposed. The selected lines were advanced to preliminary yield trials in the third summer after the cross. More detailed information on the experimental population can be found in Smith et al. (2010) and Smith et al. (2013).

DNA extraction and genotyping

DNA was extracted from a single F4:6 seedling from each breeding line and from a bulk of five or more seedlings for each of the exotic donor lines using the CTAB and chloroform method (Sambrook et al. 1989). The 1536 SNPs assayed here [barley oligonucleotide pool assay 1 (BOPA1)] were identified based on Sanger resequencing of expressed sequence tags, where Morex (an important historical Minnesota cultivar) is the most frequently represented genotype (Close et al. 2009). Genotyping was conducted at the USDA-ARS Regional Small Grains Genotyping Laboratory at Fargo, North Dakota. All lines were genotyped with BOPA1 SNPs using Illumina GoldenGate technology (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Genotypes were called using the Illumina Beadstation software. Eleven of the 13 donor lines were genotyped. Genotype and pedigree data from the Closed and Reopened panels are available in The Triticeae Toolbox (http://triticeaetoolbox.org/), an updated version of The Hordeum Toolbox (Blake et al. 2012). Genotypic and phenotypic data for individual lines are available for download by selecting populations labeled “MN Reopened” and “MN Closed” under “select lines by properties.”

Data analysis

As a part of SNP data quality control, all SNPs monomorphic in the combined Closed and Reopened panels were removed. We also removed SNPs and individual samples with ≥10% missing data or with ≥10% observed heterozygosity. Barley is a selfing species and progeny from breeding crosses were genotyped at the F4:6 generation, so SNPs or samples with elevated heterozygosity are likely attributable to genotyping errors. SNP positions were based on the consensus genetic map of Muñoz-Amatriaín et al. (2011) and are depicted in Supporting Information, Figure S1.

SNPs were annotated to determine the genes of origin. Annotations were performed using the SNP annotation tool, SNPMeta (T. Y. Kono, K. Seth, J. A. Poland, and P. L. Morrell, in press) based on the contextual sequence used for the Illumina SNP assay design (Close et al. 2009). SNP contextual sequences were used as BLAST queries against the NCBI nucleotide (nt) database. The best BLAST hit with an annotated coding sequence was downloaded and aligned to the SNP contextual sequence. Information, including gene name and whether the SNP causes a synonymous or nonsynonymous change, was recorded for each SNP. The majority of annotations originate from a large collection of full-length cDNAs (Sato et al. 2009; Matsumoto et al. 2011). The number of annotated barley genes within genomic regions identified in our studies was inferred using relative genetic map positions from the barley GenomeZipper (Mayer et al. 2011).

LD measured as r2 (correlation coefficient) (Hill and Robertson 1968) for all possible pairwise comparisons on each linkage group was calculated in R (R Development Core Team 2011), and the R package LDheatmap (Shin et al. 2006) was used to generate plots of LD relative to genetic distance. The package hierfstat (Goudet 2005) was used to calculate haploid FST for each SNP based on comparison of the Closed and Reopened panels, with heterozygous SNPs treated as missing data. An empirical threshold of the top 2.5% of FST values on a per-SNP basis was used to identify FST values that differed dramatically from the genome-wide average. The R package ape (Paradis et al. 2004) was used to calculate percent pairwise difference between the Closed or Reopened panels and donor lines. Other SNP descriptive statistics were calculated using the programs compute and sharedPoly from the libsequence C++ library (Thornton 2003), including number of segregating sites, number of singletons, and mean per-SNP pairwise diversity (Tajima 1983) within each of the Ancestral, Closed, and Reopened panels, and number of private and shared SNPs.

Segments of IBS were identified using GERMLINE (Gusev et al. 2009). Each SNP and a minimum of five adjacent SNPs were considered sequentially, with length of shared haplotypes extended until mismatch. IBS was calculated based on comparison of each of the Reopened lines and their respective donor or donors (Table S1). On each linkage group, we jointly considered all IBS segments based on each donor line, thus there were many overlapping IBS segments along the linkage group for each donor line. The number of IBS segments at each SNP was determined by summing over the number of lines in the Reopened panel that included an IBS segment for each SNP.

Simulation

To determine if patterns of allele frequency differentiation between the Closed and Reopened patterns could occur in the absence of selection, we performed coalescent simulation implemented in the program ms (Hudson 2002) (see details in File S1). An initial set of simulations was focused on differentiation between the Ancestral population (donor lines) and the MN breeding population, which forms the basis of the Closed panel (Figure S2). The Ancestral and Closed panels were each represented by 120 chromosomes. The Ancestral panel includes the 11 donor parents genotyped in this study supplemented with 109 lines chosen at random from parents for the barley nested association mapping (NAM) population to balance the panel size to the same as the Closed and Reopened panels and to better-represent the donor population. The NAM parents are a randomly chosen sample of USDA National Small Grains Collection and therefore represent the diverse panel of cultivated barley lines serving as a source for the donor population.

The folded site frequency spectrum (SFS) for the genotyped SNPs is skewed toward common variants (Close et al. 2009) (Figure S3A). To simulate ascertainment bias, we used a custom Python script that conditions on a discovery panel of fixed size and a minimum minor allele frequency for samples in the discovery panel. The first n chromosomes in the simulation were designated as the discovery panel, and sites that had a minor allele frequency below a user-defined threshold in the discovery panel were removed from the simulation dataset. If migration matrices were specified, then the script assumed that the first population listed was the population in which discovery was performed. Thus, SFS in simulation reflects what is observed in the empirical data.

The mutation parameter θ = 4N0μ and crossover rate parameter ρ = 4N0r, where N0 is the effective population size of the ancestral population, were adjusted to reflect observed values of percent pairwise diversity and levels of LD (mean r2) calculated using tools from the libsequence library (Thornton 2003) for each linkage group. We simulated a bottleneck in the establishment of the Closed panel that started at time T1 and ended at T2 (Figure S2). Time T1 was set to 8000 generations before present, when barley began to be disseminated from Western Asia (Pinhasi et al. 2005; Pinhasi et al. 2012), and T2 varied over a uniform distribution of 15 to 8000 generations U(15,8000). The Reopened panel started ∼15 generations ago (T3). The relative size of the Closed panel is a proportion of the donor population U(0,0.02). We refined this uniform interval for the relative size based on initial simulations.

To determine the likely time of the end of the bottleneck (T2) and the relative size of the Closed panel, we performed one million simulations and compared the simulated and observed values of pairwise diversity (PS and PO) in the Closed panel. Using rejection sampling, we retained simulations if |PS − PO|/PO < ε. After preliminary survey, we chose the acceptance rate of ε = 0.2 and confirmed that any choice of ε did not affect the result (not shown). The end of the bottleneck (T2) and the relative size were determined by averaging these simulations.

To determine the expected distribution for FST values between the Closed panel and the Reopened panel based on a neutral demographic scenario involving only migration and introgression, we compared PS and PO in the Reopened panel to estimate the migration rate from the donor lines to the Reopened panel. The previous distribution of the migration rate was sampled from U(0,10,000). The migration rate is based on 4N0m. We retained simulations if |PS − PO|/PO < ε. The most likely migration rate was determined by averaging these simulations. Using the most likely migration rate from the donor lines to the Reopened panel, we simulated the complete population history and calculated FST between the simulated Closed and Reopened panels using 100,000 simulations.

Results

Summary statistics for the Closed and Reopened panels

Quality control resulted in a data set with 990 SNPs in 237 lines. This included the elimination of 546 SNPs, 465 of which were monomorphic in both panels. We also eliminated two samples in the Closed panel and one sample in the Reopened panel because of SNP genotype quality. The average observed heterozygosity across the complete data set was 0.43%. There were 54 SNPs private to the Closed panel compared with 482 SNPs private to the Reopened panel (Table 1). There were 478 SNPs and 895 SNPs that were shared between the donor lines and the Closed and Reopened panels, respectively (Table 1). Pairwise diversity in the Closed panel was 0.15 genome-wide compared with 0.16 in the Reopened panel, indicating greater similarity among lines in the Closed panel (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary statistics for lines in the Closed and Reopened panels.

| Panel | Sample | Segregating Sites | Singletons | Mean FIS | Mean Pairwise Diversity | Percent Pairwise Difference with Donor Lines (SD) | Private SNPs | Shared SNPs | Shared SNPs with Donor Lines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestral | 120 | 933 | 11 | 0.997 | 0.41 | — | — | — | — |

| Closed | 118 | 502 | 168 | 0.945 | 0.15 | 0.084 (0.163) | 54 | 448 | 478 |

| Reopened | 119 | 930 | 112 | 0.959 | 0.16 | 0.137 (0.130) | 482 | 895 |

The summary statistics reported include sample size, number of segregating sites, number of singletons, average FIS, mean pairwise diversity, percent pairwise difference with donor lines, number of private SNPs in each population, and number of shared SNPs in each comparison. Shared SNPs refers to the comparison of the Closed and Reopened panels. SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Allele frequency differences between the Closed and Reopened panels

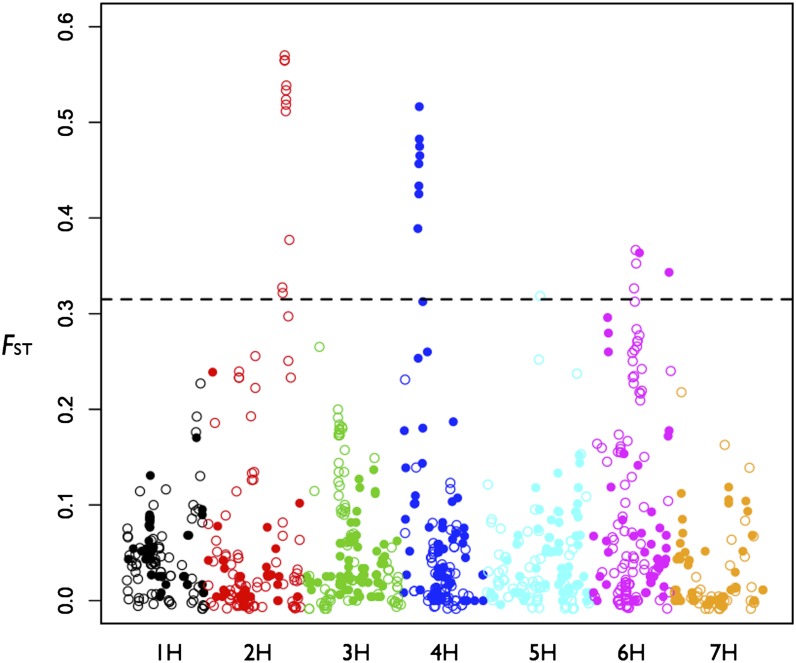

Genome-wide FST averaged 0.057 between the Closed and Reopened panels. Three genomic regions with FST values exceeding the 97.5th percentile (FST ≥ 0.315) were identified on linkage groups 2H, 4H, and 6H (Figure 2). Also, a single SNP on 5H exceeded the FST threshold. In the high FST regions on 2H and 4H, the majority of SNPs (9 out of 11 SNPs on 2H and 8 out of 9 SNPs on 4H) were above the 97.5th percentile threshold (Table 2). On 6H, only four of 20 SNPs >∼10 cM high FST region exceed the 97.5th percentile threshold.

Figure 2.

Genome-wide FST plot. The horizontal dashed line is the 97.5th percentile. Colors correspond to linkage groups. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are monomorphic in the Closed panel are represented by ● and SNPs that are polymorphic in the Closed panel are represented by ○.

Table 2. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the high FST regions on linkage group 2H, 4H, 5H, and 6H.

| LG | SNP | GenBank ID | cM | FST | Frequency Donor | Frequency Closed | Frequency Reopened |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2H | 11_10446 | XM_003560174 | 140.69 | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.07 | 0.72 |

| 11_20480 | AY162186 | 140.69 | 0.57 | 0.91 | 0.08 | 0.72 | |

| 11_21440 | AK360366 | 140.69 | 0.56 | 0.91 | 0.08 | 0.73 | |

| 11_21406 | AK370573 | 142.67 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 0.10 | 0.72 | |

| 11_21370 | AK362193 | 143.18 | 0.52 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.74 | |

| 11_11486 | X58138 | 143.18 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.73 | |

| 11_21459 | AM039897 | 143.18 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.73 | |

| 11_10109 | AK362400 | 143.71 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.11 | 0.73 | |

| 11_10065 | AK376660 | 147.37 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.15 | |

| 11_20215 | AK371957 | 147.37 | 0.25 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.15 | |

| 11_20895 | AK366193 | 149.27 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.17 | |

| 4H | 11_10132 | AK358845 | 26.20 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.60 |

| 11_20210 | AK375913 | 26.71 | 0.25 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.74 | |

| 11_20422 | XM_003560743 | 28.00 | 0.46 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.53 | |

| 11_21070 | AK355304 | 28.00 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.55 | |

| 11_20302 | AK372064 | 28.00 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.56 | |

| 11_20680 | — | 28.75 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.50 | |

| 11_21418 | X62388 | 28.75 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.53 | |

| 11_20109 | AK360657 | 29.34 | 0.47 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.49 | |

| 11_20777 | AK364484 | 29.76 | 0.47 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.47 | |

| 5H | 11_21321 | AK369180 | 97.49 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 0.37 |

| 6H | 11_10040 | AK357672 | 74.65 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| 11_10124 | AK367485 | 74.65 | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.90 | |

| 11_20015 | X95863 | 74.65 | 0.33 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.42 | |

| 11_20709 | AK363507 | 74.65 | 0.23 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 0.33 | |

| 11_20714 | AK354049 | 75.28 | 0.26 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.71 | |

| 11_20468 | AK362215 | 76.03 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.99 | 1.00 | |

| 11_21469 | — | 76.03 | 0.31 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.41 | |

| 11_20636 | AK365203 | 77.53 | 0.37 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 0.41 | |

| 11_11329 | AK364583 | 78.52 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.99 | |

| 11_20673 | HQ661104 | 78.52 | 0.35 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.42 | |

| 11_20892 | AK376359 | 79.17 | 0.28 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.31 | |

| 11_11349 | AK361558 | 80.06 | 0.27 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.31 | |

| 11_20784 | AK365537 | 80.06 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.99 | 1.00 | |

| 11_11459 | AK363684 | 80.86 | 0.27 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.69 | |

| 11_21256 | AK359524 | 80.86 | 0.27 | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.69 | |

| 11_10469 | AK355738 | 81.79 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 1.00 | |

| 11_20053 | AK370710 | 81.79 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.15 | |

| 11_20488 | AK358007 | 84.47 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.63 | |

| 11_20682 | AY029260 | 84.47 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.25 | |

| 11_20969 | — | 84.47 | 0.28 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.31 | |

| 11_11111 | AK366470 | 139.09 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.63 | |

| 11_20687 | AK366288 | 139.09 | 0.18 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

Frequency Donor is the frequency of donor alleles (the major alleles in the donor lines). Frequency Closed and Frequency Reopened are the frequency in the Closed and the Reopened panels, respectively, of the donor alleles. LG, linkage group; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; ID, identification.

Comparison of minor allele frequency (MAF) demonstrated that, genome-wide, there were far fewer SNPs segregating in the Closed than the Reopened panels (Figure S1). The three primary regions on 2H, 4H, and 6H with the largest difference in MAF between the Closed and Reopened panels corresponded to the three high FST blocks on these linkage groups. In the Closed panel, all SNPs in the high FST block on 4H were monomorphic, but they were polymorphic in the Reopened panel (Figure 2). FST plotted relative to MAF also showed the three clusters on these three linkage groups and indicated that SNPs with high FST on each linkage group also shared similar MAF (Figure S4).

The majority allele in the donor lines (donor allele) tended to occur at higher frequencies in the Reopened panel than in the Closed panel. In the high FST region on 2H, the frequency of the majority donor allele was substantially higher in the Reopened panel compared to the Closed panel for 8 out of the 11 SNPs (Table 2). The region on 4H was monomorphic in the Closed panel, and donor alleles introduced novel variants to the Reopened panel. All 22 SNPs in the high FST regions on 6H were either monomorphic or had low MAF in the Closed panel but were more polymorphic in the Reopened panel (Table 2).

One feature of the MAF that could not be explained by donor introgression is a region involving 34 SNPs at 64–81 cM on linkage group 3H with ∼0.3 MAF in the Closed panel (Figure S1). There were two primary haplotypes for these 34 SNPs (data not shown).

Simulation

A discovery panel of eight chromosomes with a minimum minor allele count of three reflected the design parameters of the barley OPAs (Close et al. 2009). In simulations of the Ancestral population, this discovery scheme also closely matched the observed SFS (Figure S3) (paired t-test p-value = 1).

When including the Closed panel in the model, the median of simulated pairwise diversity along each linkage group in the Ancestral panel was 0.054 (95% CI, 0.42–0.68). In the Closed panel, the median of simulated pairwise diversity was 0.007 and pairwise diversity was zero in 35% of simulations. The pairwise diversity in both the Ancestral panel and the Closed panel provided a close fit to the observed data (Table S2). In our simulations, there was convergence in posterior density of relative size of the Closed panel, which was ∼1% of the Ancestral population (Figure S5). There was a wide interval for the most likely timing of the end of the bottleneck, which varied across the range of prior values. When we plotted the density of these two parameters together, the most likely timing of the end of the bottleneck corresponded to the highest likelihood of the relative size, which was at 0.0015, ∼900 generations ago (Figure S6). The relative size of the bottleneck and duration of the bottleneck were confounded as suggested by a previous study (Eyre-Walker et al. 1998).

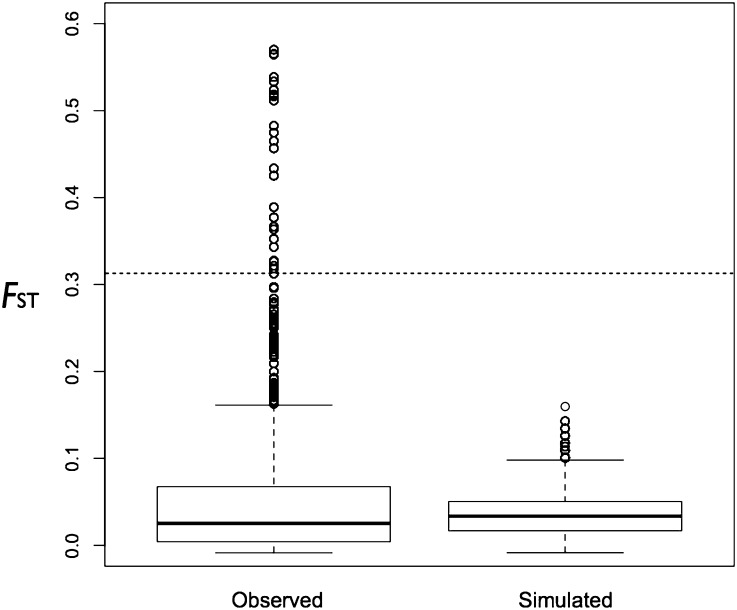

Adding the Reopened panel to the simulation, and simulating migration, the estimated migration rate was 4N0m = 4000, which corresponded to 0.01 migrants per generation over 15 generations (Figure S7). In these simulations, in which demography alone impacted allele frequency (i.e., where we were testing a neutral null hypothesis), the 97.5th percentile of FST was 0.09 between the simulated Closed and Reopened panel compared with FST of 0.315 in the empirical data (Figure 3). This suggests that in the absence of selection, demography alone is unlikely to produce the extreme values of FST observed between the Closed and Reopened panels.

Figure 3.

The boxplots for observed and simulated FST between the Closed and Reopened panels. Simulations were based on demography alone. The dashed horizontal line is the 97.5th percentile of FST in the empirical data.

Segments of IBS

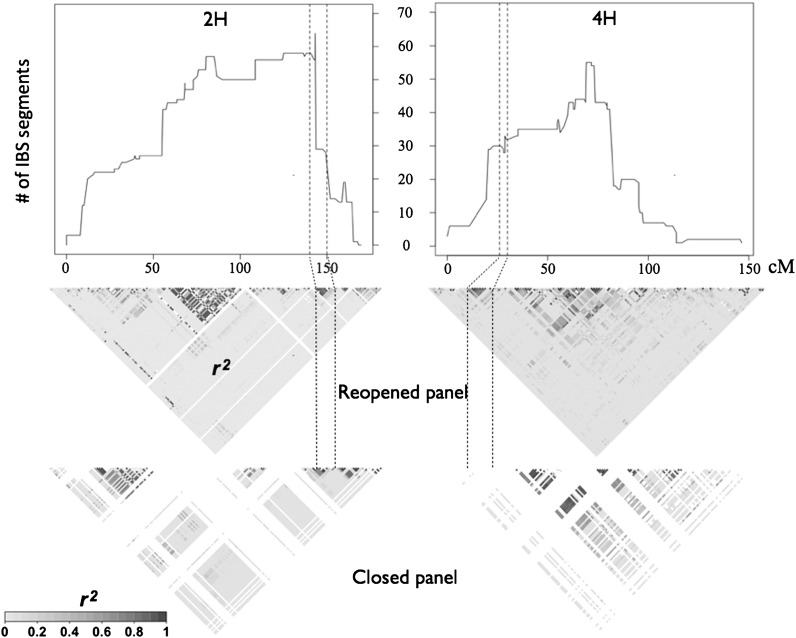

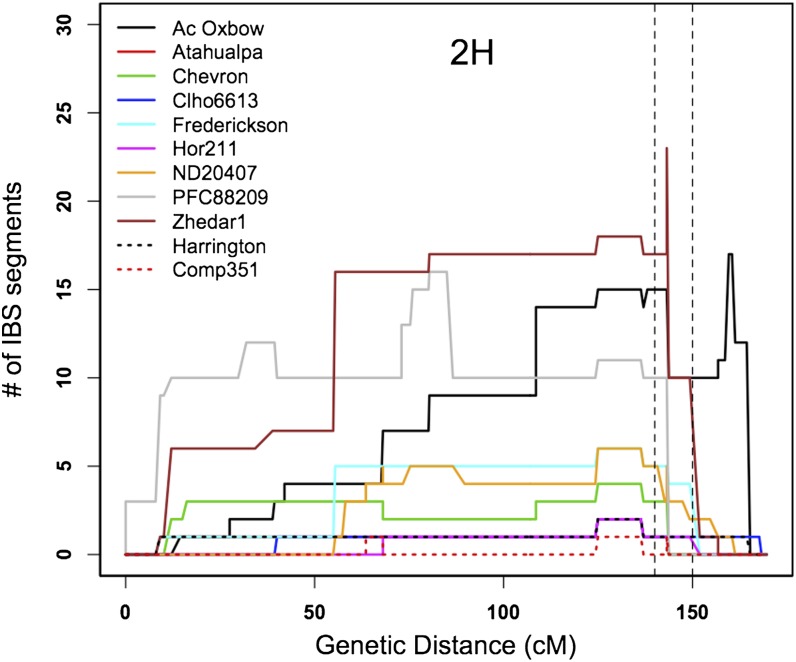

Individual donors contributed to an average of 12 progeny in the Reopened panel. Zhedar1 contributed to the largest number of progeny, 49, whereas Comp351 and BT463 contributed to only a single individual (Table S1). The highest degree of IBS between the donor lines and their progeny in the Reopened panel on 2H and 6H overlapped the high FST regions (Figure 4 and Figure S8). However, the highest IBS region on 4H did not overlap with the high FST region, but rather it occurred ∼40 cM away (Figure 4). This resulted from a localized contribution of high IBS from donor Hor211 to 24 progeny; excluding this donor, the highest degree of IBS on 4H also overlapped with the high FST region for most donor lines (Figure S9). The degree of IBS declines dramatically at both ends of the chromosome, where SNP number limits the potential to identify long segments that were IBS. Donor line Zhedar1 contributed most to the Reopened panel in the high FST region on 2H (Figure 5), whereas PFC88209 contributed most to the high FST regions on 4H and 6H (Figure S9). We summed the number of IBS segments at each SNP across the genome and across the three major high FST regions. We found little correlation between the timing of introgression of donor lines and the number of IBS segments genome-wide (r2 = 0.20) as well as in the high FST regions (r2 = 0.10).

Figure 4.

Identity-by-state (IBS) and linkage disequilibrium (LD) plot to linkage groups 2H and 4H. The upper panel shows number of IBS segments between the donor lines and their progeny in the Reopened panel. The vertical dashed lines delimit the high FST block. The middle and lower panels are LD heatmaps of the Reopened and Closed panels, respectively.

Figure 5.

Identity-by state (IBS) between each of the donor lines and their respective progeny in the Reopened panel on 2H. The vertical dashed lines delimit the high FST block.

LD in the Closed and Reopened panels

Average genome-wide LD (r2) among all pairs of SNPs was higher in the Closed panel (0.051) than in the Reopened panel (0.028). LD between adjacent SNPs was also higher in the Closed panel (0.653) compared with the Reopened panel (0.490) (Figure S10).

Blocks of LD were defined as sets of at least three adjacent SNPs that showed greater LD than the median r2 of adjacent SNPs (0.58). There were 28 blocks in the Closed panel covering a total of 65.13 cM and 45 blocks in the Reopened panel covering a total of 80.63 cM. The average block size in the Closed panel was 2.33 cM, which was greater than that in the Reopened panel (1.79 cM). In the Closed panel, 15.9% of SNPs were in LD blocks, whereas 21.8% of SNPs were in blocks in the Reopened panel.

All the SNPs in the two high FST blocks on linkage groups 2H and 4H were also in high LD (r2 > 0.21, the 97.5th percentile threshold) with each other in the Reopened panel (Figure 4). The LD pattern was less clear in the linkage group 2H block in the Closed panel (r2 = 0.477 vs. 0.613) and the SNPs were monomorphic in the linkage group 4H block in the Closed panel (Figure 4). The LD in the high FST region on 6H was similar in the Closed and Reopened panels (r2 = 0.438) (Figure S8).

Comparison to previous studies

We identified markers from previous studies that occur in genetic map locations adjacent to high FST genomic regions in our comparison (Table S3). The high FST regions on 2H, 4H, and 6H overlapped with the relative genetic map positions of markers associated with DON concentration and FHB resistance in previous QTL mapping studies (Ma et al. 2000; Mesfin et al. 2003) as well as in a recent GWAS study that included elite breeding lines from four Midwest breeding programs, including the University of Minnesota program (Massman et al. 2011).

In addition to SNPs surveyed here (BOPA1), three additional sets of SNPs have been mapped in barley genetic mapping populations (Rostoks et al. 2005; Close et al. 2009; Muñoz-Amatriaín et al. 2011). All BOPA1, BOPA2, pilot oligonucleotide pool assays (POPA), and Scottish Crop Research Institute (SCRI; the SCRI is now known as the James Hutton Institute) SNPs (http://bioinf.hutton.ac.uk/iselect/app/) that fall within annotated genes in the high FST blocks on 2H, 4H, and 6H are listed in Table S4. The genomic regions identified are ∼5 cM (4H) and ∼10 cM (2H and 6H) and include a minimum of 40 (on 4H) or 100 genes (on 2H and 6H).

Discussion

Several genomic regions putatively subject to selection have been identified using comparative population genetic methods in this barley experimental population. These regions show strong allele frequency differentiation between the Closed and Reopened panels, excess IBS between the Reopened panel and donor lines, and elevated LD in the Reopened panel.

Variability of allele frequency

In the donor lines Chevron and Frederickson, QTL contributing to FHB resistance have been mapped to the same interval found to have high FST on 2H and 6H (de la Pena et al. 1999; Ma et al. 2000; Mesfin et al. 2003; Massman et al. 2011). The SNPs in the two intervals on linkage groups 2H and 4H have FST values in the top 2.5% genome-wide. The plot of FST vs. MAF (Figure S4) shows clusters of high FST SNPs on the same linkage group having similar MAF, which suggests these SNPs co-occur, potentially because of selection favoring a relatively small number of haplotypes. Interestingly, all SNPs in the high FST block on 2H are polymorphic within the Closed panel, but SNPs in the high FST block on 4H are monomorphic in the Closed panel (Figure 2 and Table 2). Within the limits of the experiment, this suggests that selection at 4H is more likely to have acted on newly introgressed allelic variation.

In this experimental population, allele frequency changes appear to provide an effective means of identifying genomic regions subject to selection. However, there are limitations to this approach. First, selection on FHB phenotypes is at least partially confounded with selection for agronomically adaptive phenotypes, particularly in the parent used for later generation crosses in the recipient (Reopened) population. Although there are QTL associated with heading date and plant height that are coincident with FHB or DON in the high FST region on 2H and 4H, the QTL associated with heading date and plant height on 6H are not within the high FST regions based on the association mapping study by Massman et al. (2011). Second, the family structure within the population may tend to inflate differences in SNP frequency. Third, as with any outlier-based approach, extreme values of FST could result from stochastic processes and thus would represent false-positives when attributed to selection. Finally, in the present study, genetic resolution is limited and differences in allele frequency likely reflect only the general proximity of causative mutations. The level of genetic resolution provided by the high FST regions is comparable to association mapping studies in plant breeding populations (Cockram et al. 2010; Massman et al. 2011) and is not a major impediment to the utilization of the identified genomic regions in marker-assisted breeding or genomic selection approaches.

Variability of IBS

Along with assaying allele frequency changes, we used IBS analysis to identify regions that were putatively subject to selection. The high IBS regions on 2H and 6H were within or adjacent to the high FST regions (Figure 4 and Figure S8). The IBS analysis identified a narrower region, because the number of IBS segments at SNP 11_21459 on 2H was much higher than that at both adjacent SNPs. However, the excess IBS region in the high FST region on 4H did not have the highest number of IBS segment on this linkage group (Figure 4), which was primarily contributed by one donor line, Hor211 (Figure S9).

The IBS analysis also has limitations. The timing of introgression of donor lines could influence IBS results, because the lines introgressed recently would have more IBS segments. However, our results show that a strong correlation does not exist between the timing of introgression and the number of IBS segments, and the two donor lines PFC88209 and Zhedar1 that contributed most to the high FST regions were not among the most recently used donors (Figure 1).

Variability of LD

The distribution and pattern of LD (r2) differed dramatically between these two panels (Figure 4 and Figure S10). The introduction of allelic diversity to the Reopened panel resulted in a larger number of polymorphic SNPs and a reduction in both average genome-wide and average adjacent SNP LD within this population. Although average LD was lower in the Reopened panel, the LD was higher in the two high FST regions on linkage groups 2H and 4H in the Reopened panel, as can occur in genomic regions subject to recent strong selection (Sabeti et al. 2002; McVean 2007) (Figure 4). Therefore, the blocks of LD in the Reopened panel on linkage groups 2H, 4H, and 6H likely resulted from selection on haplotypes for FHB resistance or reduction in DON accumulation. A number of other factors, however, could potentially contribute to localized elevation of LD, including recent admixture (Pfaff et al. 2001) or suppressed recombination attributable to chromosomal structural variation (Graubard 1932; Fang et al. 2012).

Introducing genetic diversity and shifting selection pressure changes the distribution and pattern of LD among markers and, therefore, between markers and QTL. This suggests that it will be important to use panels of germplasm that are contemporary and relevant to current breeding goals for association analysis and generating prediction models for genomic selection. As genetic distance between two breeding populations increases, the correlation between closely linked markers in the two populations decreases. Based on this, Hamblin et al. (2010) cautioned against pooling data from different breeding programs for association analyses. However, similar concerns may apply to populations within a breeding program that have different breeding histories. Recent work evaluating genomic selection prediction accuracy has shown that using a training population from distinct but closely related breeding programs provides less accurate predictions than from a training population representing the target breeding population (Lorenz et al. 2012).

Conclusion

We have used population genetic approaches to identify genomic regions putatively subject to selection subsequent to introgression in a barley breeding experiment. The progenitor-derivative relationship between the two populations in our study is among the simplest possible scenarios for detecting the effects of recent strong selection (Innan and Kim 2008). Other comparative analyses of plant breeding history generally deal with more diverse breeding histories over longer periods of time (Sim et al. 2010; van Heerwaarden et al. 2012), making inference of the selective pressure on outlier loci more difficult. The identification of the genomic regions previously associated with FHB resistance and DON concentration suggests that the comparative approach applied here is complementary to the identification of trait-associated markers through QTL and association mapping approaches.

There are several advantages to the comparative approach as applied here. The first is the relative speed and minimal expense associated with identification of putatively trait-associated loci. This experiment was conducted within the confines of a breeding program, obviating the need for multiple QTL mapping populations to identify sources of resistance. The program developed two high-yielding malting cultivars from material represented in this population. Rasmusson is representative of the Closed population (Smith et al. 2010), whereas Quest (Smith et al. 2013), a cultivar with reduced DON accumulation, is derived from donor parents Chevron and Zhedar1 and is a product of the Reopened population. Second, comparison of allele frequencies among populations will remain effective even as divergence and low minor allele frequencies within populations minimize the potential for effective association mapping. Finally, the comparative population genetic approach is also free of a priori identification of phenotypes to be measured and can benefit dramatically from increased SNP density (Ross-Ibarra et al. 2007; Walsh 2008). We note that although we identified interesting genomic regions without the use of phenotype data in our two panels, the approach is not “phenotype-free,” but rather the result of repeated strong phenotypic selection.

The fact that we identified signals of selection for FHB resistance that are substantiated by previous mapping efforts in barley suggests that this approach may also be effective when applied to crop species without previous information from QTL mapping. Application of inexpensive genotyping to any breeding population that has a defined history of breeding and selection should provide valuable insight into the genetic architecture of the traits under selection and guidance for marker-based breeding efforts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ed Scheifelbein, Karen Beaubien, and Shiaoman Chao for SNP genotyping. Ana Gonzales, Matthew Hufford, Sofiane Mezmouk, Mohsen Mohammadi, Tanja Pyhäjärvi, Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra, and two anonymous reviewers provided discussion and helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This work was performed, in part, using hardware and software provided by the University of Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. We acknowledge funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute for Food and Agriculture USDA NIFA, 2006-55606-16722 for support (to K.P.S.), USDA NIFA 2011-68002-30029 for support (to K.P.S. and P.L.M.), USDA NIFA 2011-38420-20068 for support (to P.L.M.), and the University of Minnesota Faculty Grant-in-Aid of Research (to P.L.M.).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: D. Zamir

Literature Cited

- Albrechtsen A., Moltke I., Nielsen R., 2010. Natural selection and the distribution of identity-by-descent in the human genome. Genetics 186: 295–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard R. W., Kahler A. L., Weir B. S., 1972. The effect of selection on esterase allozymes in a barley population. Genetics 72: 489–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake V. C., Kling J. G., Hayes P. M., Jannink J. L., 2012. The Hordeum Toolbox - The Barley Coordinated Agricultural Project genotype and phenotype resource. The Plant Genome 5: 81–91 [Google Scholar]

- Burke M. K., Rose M. R., 2009. Experimental evolution with Drosophila. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 296: R1847–R1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke M. K., Dunham J. P., Shahrestani P., Thornton K. R., Rose M. R., et al. , 2010. Genome-wide analysis of a long-term evolution experiment with Drosophila. Nature 467: 587–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg M. T., Allard R. W., Kahler A. L., 1972. Is the gene the unit of selection? Evidence from two experimental plant populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 69: 2474–2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close T. J., Bhat P. R., Lonardi S., Wu Y., Rostoks N., et al. , 2009. Development and implementation of high-throughput SNP genotyping in barley. BMC Genomics 10: 582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockram J., White J., Zuluaga D. L., Smith D., Comadran J., et al. , 2010. Genome-wide association mapping to candidate polymorphism resolution in the unsequenced barley genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 21611–21616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condón F., Gustus C., Rasmusson D. C., Smith K. P., 2008. Effect of advanced cycle breeding on genetic diversity in barley breeding germplasm. Crop Sci. 48: 1027–1036 [Google Scholar]

- Condón F., Rasmusson D. C., Schiefelbein E., Velasquez G., Smith K. P., 2009. Effect of advanced cycle breeding on genetic gain and phenotypic diversity in barley breeding germplasm. Crop Sci. 49: 1751–1761 [Google Scholar]

- de la Pena R. C., Smith K. P., Capettini F., Muehlbauer G. J., Gallo-Meagher M., et al. , 1999. Quantitative trait loci associated with resistance to Fusarium head blight and kernel discoloration in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 99: 561–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley J. W., Lambert R. J., 2004. 100 generations of selection for oil and protein in corn. Plant Breed. Rev. 24: 79–110 [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., Gaut R. L., Hilton H., Feldman D. L., Gaut B. S., 1998. Investigation of the bottleneck leading to the domestication of maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 4441–4446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z., Pyhäjärvi T., Weber A., Dawe R. K., Glaubitz J., et al. , 2012. Megabase-scale inversion polymorphism in the wild ancestor of maize. Genetics 191: 883–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetch T. G., Steffenson B. J., Nevo E., 2003. Diversity and sources of multiple disease resistance in Hordeum spontaneum. Plant Dis. 87: 1439–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet J., 2005. Hierfstat, a package for R to compute and test hierarchical F‐statistics. Mol. Ecol. Notes 5: 184–186 [Google Scholar]

- Graubard M. A., 1932. Inversion in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 17: 81–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusev A., Lowe J. K., Stoffel M., Daly M. J., Altshuler D., et al. , 2009. Whole population, genome-wide mapping of hidden relatedness. Genome Res. 19: 318–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin M. T., Close T. J., Bhat P. R., Chao S., Kling J. G., et al. , 2010. Population structure and linkage disequilibrium in US barley germplasm: implications for association mapping. Crop Sci. 50: 556–566 [Google Scholar]

- Harlan H. V., Martini M. L., 1929. A composite hybrid mixture. J. Am. Soc. Agron. 21: 487–490 [Google Scholar]

- Hill W. G., Robertson A., 1968. Linkage disequilibrium in finite populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 38: 226–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R., 2002. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics 18: 337–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innan H., Kim Y., 2008. Detecting local adaptation using the joint sampling of polymorphism data in the parental and derived populations. Genetics 179: 1713–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Chee P. W., Draye X., Morrell P. L., Smith C. W., et al. , 2000. Multilocus interactions restrict gene introgression in interspecific populations of polyploid Gossypium (cotton). Evolution 54: 798–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono T. Y., Seth K., Poland J. A., Morrell P. L. 2013. SNPMeta: SNP annotation and SNP Metadata collection without a reference genome. Mol. Ecol. Resour. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin R. C., Krakauer J., 1973. Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of the selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. R., Schertz K. F., Paterson A. H., 1995. Comparative analysis of QTLs affecting plant height and maturity across the Poaceae, in reference to an interspecific sorghum population. Genetics 141: 391–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz A. J., Smith K. P., Jannink J. L., 2012. Potential and optimization of genomic selection for Fusarium head blight resistance in six-row barley. Crop Sci. 52: 1609–1621 [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Steffenson B. J., Prom L. K., Lapitan N. L. V., 2000. Mapping of quantitative trait loci for Fusarium head blight resistance in barley. Phytopathology 90: 1079–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. M., Blake T. K., Hockett E. A., 1991. Diversity among North American spring barley cultivars based on coefficients of parentage. Crop Sci. 31: 1131–1137 [Google Scholar]

- Massman J., Cooper B., Horsley R., Neate S., Dill-Macky R., et al. , 2011. Genome-wide association mapping of Fusarium head blight resistance in contemporary barley breeding germplasm. Mol. Breed. 27: 439–454 [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T., Tanaka T., Sakai H., Amano N., Kanamori H., et al. , 2011. Comprehensive sequence analysis of 24,783 barley full-length cDNAs derived from 12 clone libraries. Plant Physiol. 156: 20–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K. F., Martis M., Hedley P. E., Simkova H., Liu H., et al. , 2011. Unlocking the barley genome by chromosomal and comparative genomics. Plant Cell 23: 1249–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen M., Jones R., Gallenberg D., 1997. Scab of wheat and barley: a re-emerging disease of devastating impact. Plant Dis. 81: 1340–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean G., 2007. The structure of linkage disequilibrium around a selective sweep. Genetics 175: 1395–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesfin A., Smith K. P., Waugh R., Dill-Macky R., Evans C. K., et al. , 2003. Quantitative trait loci for Fusarium head blight resistance in barley detected in a two-rowed by six-rowed population. Crop Sci. 43: 307–318 [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Amatriaín M., Moscou M. J., Bhat P. R., 2011. An improved consensus linkage map of barley based on flow-sorted chromosomes and single nucleotide polymorphism markers. The Plant Genome 4: 238–249 [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Terwengel P., Kapun M., Nolte V., Kofler R., Flatt T., et al. , 2012. Adaptation of Drosophila to a novel laboratory environment reveals temporally heterogeneous trajectories of selected alleles. Mol. Ecol. 21: 4931–4941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E., Claude J., Strimmer K., 2004. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20: 289–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff C. L., Parra E. J., Bonilla C., Hiester K., McKeigue P. M., et al. , 2001. Population structure in admixed populations: effect of admixture dynamics on the pattern of linkage disequilibrium. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68: 198–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhasi R., Fort J., Ammerman A. J., 2005. Tracing the origin and spread of agriculture in Europe. PLoS Biol. 3: e410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhasi R., Thomas M. G., Hofreiter M., Currat M., Burger J., 2012. The genetic history of Europeans. Trends Genet. 28: 496–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team, 2011 R: A language and environment for statistical computing, version 2.12.2. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. http://www.r-project.org

- Rasmusson D. C., Phillips R. L., 1997. Plant breeding progress and genetic diversity from de novo variation and elevated epistasis. Crop Sci. 37: 303–310 [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg L. H., Sinervo B., Linder C. R., Ungerer M. C., Arias D. M., 1996. Role of gene interactions in hybrid speciation: evidence from ancient and experimental hybrids. Science 272: 741–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Ibarra J., Morrell P. L., Gaut B. S., 2007. Plant domestication, a unique opportunity to identify the genetic basis of adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 8641–8648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostoks N., Mudie S., Cardle L., Russell J., Ramsay L., et al. , 2005. Genome-wide SNP discovery and linkage analysis in barley based on genes responsive to abiotic stress. Mol. Genet. Genomics 274: 515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti P. C., Reich D. E., Higgins J. M., Levine H. Z. P., Richter D. J., et al. , 2002. Detecting recent positive selection in the human genome from haplotype structure. Nature 419: 832–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis, 1989 Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual, Ed. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Shin-I T., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Yoshida H., et al. , 2009. Development of 5006 full-length cDNAs in barley: a tool for accessing cereal genomics resources. DNA Res. 16: 81–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. H., Blay S., McNeney B., Graham J., 2006. LDheatmap: an R function for graphical display of pairwise linkage disequilibria between single nucleotide polymorphisms. J. Stat. Softw. 16: 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Sim S. C., Robbins M. D., Van Deynze A., Michel A. P., Francis D. M., 2010. Population structure and genetic differentiation associated with breeding history and selection in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Heredity 106: 927–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. P., Rasmusson D. C., Schiefelbein E., Wiersma J. J., Wiersma J. V., et al. , 2010. Registration of ‘Rasmusson’ barley. J. Plant Reg. 4: 167–170 [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. P., Budde A., Dill-Macky R., Rasmusson D. C., Schiefelbein E., et al. , 2013. Registration of ‘Quest’ spring malting barley with improved resistance to Fusarium head blight. J. Plant Reg. 7: 125–129 [Google Scholar]

- Suneson C. A., 1956. An evolutionary plant breeding method. Agron. J. 48: 188–191 [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F., 1983. Evolutionary relationship of DNA sequences in finite populations. Genetics 105: 437–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaillon O., Rodríguez-Verdugo A., Gaut R. L., McDonald P., Bennett A. F., et al. , 2012. The molecular diversity of adaptive convergence. Science 335: 457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teotónio H., Chelo I. M., Bradic M., Rose M. R., Long A. D., 2009. Experimental evolution reveals natural selection on standing genetic variation. Nat. Genet. 41: 251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton K., 2003. Libsequence: a C++ class library for evolutionary genetic analysis. Bioinformatics 19: 2325–2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner T. L., Stewart A. D., Fields A. T., Rice W. R., Tarone A. M., 2011. Population-based resequencing of experimentally evolved populations reveals the genetic basis of body size variation in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 7: e1001336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heerwaarden J., Hufford M. B., Ross-Ibarra J., 2012. Historical genomics of North American maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 12420–12425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh B., 2008. Using molecular markers for detecting domestication, improvement, and adaptation genes. Euphytica 161: 1–17 [Google Scholar]

- Weir B. S., Allard R. W., Kahler A. L., 1972. Analysis of complex allozyme polymorphisms in a barley population. Genetics 72: 505–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.