Abstract

Knowing health literacy levels of older patients and their caregivers is important because caregivers assist patients in the administration of medications, manage daily health care tasks, and help make health services utilization decisions. The authors examined the association of health literacy levels between older Hispanic patients and their caregivers among 174 patient-caregiver dyads enrolled from 3 community clinics and 28 senior centers in San Antonio, Texas. Health literacy was measured using English and Spanish versions of the Short-Test of Functional Health Literacy Assessment and categorized as “low” or “adequate.” The largest dyad category (41%) consisted of a caregiver with adequate health literacy and patient with low health literacy. Among the dyads with the same health literacy levels, 28% had adequate health literacy and 24% had low health literacy. It is notable that 7% of dyads consisted of a caregiver with low health literacy and a patient with adequate health literacy. Low health literacy is a concern not only for older Hispanic patients but also for their caregivers. To provide optimal care, clinicians must ensure that information is given to both patients and their caregivers in clear effective ways as it may significantly affect patient health outcomes.

Low health literacy is a major problem in the United States. It is estimated that approximately 80 million people in the United States have limited health literacy (Berkman, Sheridan, Donahue, Halpern, & Crotty, 2011). On the basis of the Institute of Medicine's definition, this is defined as a limited “capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Ratzan & Parker, 2000). The 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy survey, which used the Institute of Medicine's definition, reported that nearly 1 in 6 Americans possess only the most simple health literacy skills (Kutner, U.S. Department of Education, & National Center for Education Statistics, 2006). A 2003–2011 systematic review of the English language literature documented that patients with low health literacy compared with patients whose health literacy is adequate have worse health outcomes, more hospitalizations and emergency room use, and fewer health maintenance and preventative medicine services, such as mammography screenings and immunizations (Berkman et al., 2011). Proceedings from the Surgeon General's workshop on improving health literacy also noted the strong association between low health literacy and poor health outcomes, such as emergency department use, hospitalization, self-reported health, and mortality (Office of the Surgeon General and the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2006). Economists estimate that the adverse consequences of low health literacy add $106 billion to $238 billion annually to U.S. health care costs (Vernon, Trujillo, Rosenbaum, & DeBuono, 2007).

Hispanics are disproportionately represented among persons with low health literacy and, in 2003, comprised 41% of U.S. adults with below basic health literacy (Kutner, 2006). Older Hispanics—the fastest growing subgroup among older U.S. adults (Federal Interagency Forum On Aging-Related Statistics, 2010)—are at greater risk than younger Hispanics of having inadequate health literacy (Kutner, 2006). A study of 414 older adults older than 60 years of age living in New York City found that among those with inadequate health literacy, more than half were Hispanic (Federman, Sano, Wolf, Siu, & Halm, 2009). Compounding the problem of low health literacy, older Hispanics are more likely than older European Americans are to report functional limitations and disabilities (Carrasquillo, Lantigua, & Shea, 2000; Ostchega, Harris, Hirsch, Parsons, & Kington, 2000). However, older Hispanics are less likely than European Americans are to use community-based long-term care services (Aranda & Knight, 1997); instead, they frequently rely on informal caregivers such as spouses, family members, or friends (Weiss, Hector, Mohammed, & Kenneth, 2005).

As persons age, the onset of cognitive impairment erodes the capacity to comprehend and act on health information. Given that advancing age is a correlate of low health literacy (Baker, Gazmararian, Sudano, & Patterson, 2000), the presence of a caregiver may safeguard individuals in assuring their effective use of health services. Caregivers play a major role in encouraging medication adherence, interpreting medical information, communicating with providers, making decisions about when to seek medical treatment, learning and performing technical procedures (e.g., wound care), and acting as translators for patients who are not proficient in English (Bevan & Loretta, 2008). Nonetheless, little is known about the caregiver's health literacy, its association with the patient's health literacy, and its potential effect on the capacity of the dyad to use health services effectively for the older adult. Although there are several studies on the health literacy of caregivers of children, there is only one published study that examined the health literacy of paid caregivers of older adults, which reported that the rate of low health literacy in this group of caregivers is high (Lindquist, Jain, Tam, Martin, & Baker, 2010).

The purpose of the present study was to measure the level of health literacy among dyads of Hispanic older adults (patients) and their caregivers to determine the patterns of association within dyads and the correlates of low health literacy in both patients and their caregivers. Many clinicians assume that caregivers will have the same or greater level of health literacy when compared with the patient. Therefore, we hypothesized that low or high levels of health literacy among caregivers would be associated with matching low or high levels of health literacy in their patients.

Method

Patients

We recruited 174 patient–caregiver dyads from outpatient clinics (70 dyads) and community senior centers (104 dyads) in San Antonio, Texas, from November 2010 to August 2011. Outpatient clinics included (a) the Veterans Administration Geriatric Evaluation and Management clinic, (b) the CHRISTUS Santa Rosa Senior Health Clinic in downtown San Antonio, and (c) the University of Texas Medical Arts and Research Center Geriatrics Clinic. Individuals were recruited in clinics using informational flyers at the time of clinic check-in and also by primary care physician referral to the study team. Community senior centers included 28 centers in socioeconomically diverse locations across San Antonio. Individuals recruited through community centers were recruited with the use of flyers and brochures available in the center as well as informational presentations made by a member of the study team (C.G.).

Data were collected through 45-minute in-person interviews. Interviews were conducted by trained, bilingual staff using standardized protocols and administered in English or Spanish (on the basis of the participant's stated preference). Participants were given the option of doing the interview on site (where recruited) or in their homes. Study visits comprised three parts: (a) an oral interview to obtain demographic data, (b) assessments of health status and acculturation, and (c) a self-administered measurement of health literacy.

Inclusion criteria were the following: (a) being a community-dwelling older adult (65 years of age or older) who (b) had a caregiver and (c) self-identified as Hispanic. At clinic sites, the patient was defined as the individual being served by the health providers. In senior centers, dyads were identified; then, the patient was defined as the individual who acknowledged receiving greater care and support (instrumental, physical, emotional, and mental) from the other dyad member. Caregivers had to be at least 18 years old but could be from any ethnic group. Both patient and caregiver had to agree to participate.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) vision score worse than 20/100 using the Rosenbaum handheld eye chart, (b) score less than 18 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) or (c) too ill to participate. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio approved the study, and all participants gave informed consent.

Measures

Age

Age was self-reported by patients and caregivers and described both as a continuous and categorical variable collapsed into four groups: <65, 65–70, 71–80, and >80 years. Age was used as a categorical variable in the multivariable model.

Education Level

The highest number of years of schooling completed was obtained by self-report. Years of education were described both as a continuous and categorical variable (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate). In the multivariable model, education was included as a categorical variable.

Caregiver Relationship

Caregiver's relationship to the patient was ascertained by caregiver self-report. Categories included spouse/partner (n = 111), family member (n = 49), hired caregiver (n = 8), and unpaid friend (n = 6). In the multivariable model, caregiver was treated as a dichotomous variable categorized as a spouse/partner relationship versus any other relationship (family member, hired caregiver, or friend).

Vision

Binocular, corrected vision was treated as a continuous variable. Vision was assessed in a well-lit area using a Rosenbaum Handheld Vision Chart (range = 20/20 to 20/100). Higher numbers in the range represent poorer vision. Participants were asked to read the smallest line they could see. If more than two mistakes were made, they were asked to read the next largest line.

MMSE

Cognitive function was assessed using the MMSE (range = 0–30), available in English and Spanish. MMSE was treated as a continuous variable, with higher scores indicating better cognitive function. (Espino, Lichtenstein, Palmer, & Hazuda, 2001, 2004; Folstein et al., 1975).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the 15-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (range = 0–15; D'Ath, Katona, Mullan, Evans, & Katona, 1994) available in English and Spanish (Ortega Orcos, Salinero Fort, Kazemzadeh Khajoui, Vidal Aparicio, & de Dios del Valle, R., 2007). The Geriatric Depression Scale was treated as a continuous variable, with higher scores indicating presence of greater depressive symptoms.

Acculturation

Acculturation was defined as a multidimensional process in which individuals whose primary learning has been in one culture (e.g., the Mexican or Mexican-American culture) take over characteristic ways of living (i.e., language, attitudes, values, and behavior) from another culture (e.g., the broader American culture). Because we believed that language usage was the most salient dimension to assess relative to health literacy, we measured that dimension of acculturation with the 10-item Hazuda Adult English versus Spanish Language Usage scale, (Hazuda, Haffner, Stern, & Eifler, 1988), which assesses the language an individual uses with family members, friends, neighbors, and coworkers, as well as the language of the TV shows they watch, radio stations they listen to, and books they read. The instrument is validated in both English and Spanish. Item responses are as follows: only Spanish, mostly Spanish, Spanish and English equally, mostly English, and only English. Scores range from 0 to 50 (higher scores indicate greater use of English relative to Spanish-language usage) and are categorized into four rank-ordered strata from least (lowest strata) to most acculturated (highest strata). The four rank-ordered strata (range = 1–4) were treated as a linear trend variable.

Health Literacy Level

Health literacy was measured using the reading portion of the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy Assessment (S-TOFHLA). The S-TOFHLA takes approximately 7 minutes to complete and is validated in both English and Spanish (Baker, Williams, Parker, Gazmararian, & Nurss, 1999). The 36-item S-TOFHLA uses a modified Cloze procedure to measure reading comprehension. It consists of two reading passages: one about preparation for an upper GI series (written at the 4th-grade level), the second about patients' rights and responsibilities from a Medicaid application form (written at the 10th-grade level). Score range is 0–36, with higher scores indicating better literacy. Scores are stratified into inadequate (0–16), marginal (17–22), or adequate health literacy (23–36) (Nurss, Parker, Williams, & Baker, 1998). Individuals with marginal or inadequate health literacy will have difficulty reading, understanding, and interpreting most written health materials (Nurss et al., 1998). Because of the skewed distribution of S-TOHFLA categories in our sample, we combined marginal and inadequate scores into a single “low” health literacy category (0–22), which we compared with the “adequate” category (23 36). At the beginning of the interview, participants were asked in which language they wished to be interviewed, and in which language they preferred to receive written health forms. Their answer to the latter question determined the language in which the S-TOFHLA was administered. The majority of patients and caregivers took the interview and S-TOFHLA in the same language (English or Spanish). Only 2 patients and 1 caregiver completed the interview and the self-administered S-TOFHLA in different languages. All three participants completed the interview in Spanish, and the S-TOFHLA in English. All survey instruments were available in both English and Spanish.

Statistical Analysis

Patient and caregiver characteristics were analyzed using either Fisher's exact test or the chi-squared statistic, as appropriate, for categorical variables and the two-sample t test statistic for continuous variables (Kirkwood & Sterne, 2003). Consistency, or matching, of health literacy levels within dyads was assessed using continuous and categorical measures of health literacy. Differences in all patient and caregiver characteristics by recruitment site (clinic vs. senior center) were also examined using t tests for continuous variables and chi-square statistics for categorical variables. Intraclass correlation coefficients were used to correlate continuous S-TOFHLA scores between patients and their caregivers; kappa statistics were used to compare categorical S-TOFHLA levels (Kirkwood & Stern, 2003). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to examine the relationship between factors potentially associated with low health literacy among patients and caregivers (Kirkwood & Stern, 2003). Low health literacy was regressed on age category, gender, education category, acculturation strata, interview language, spousal relationship, MMSE score, corrected vision score, and recruitment site. Analyses were performed with STATA/SE 11.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Compared with patients (Table 1), caregivers were more likely to be younger, female, spouses, more educated, and more acculturated. Caregivers also had better corrected vision and higher MMSE scores than patients. Both groups had little evidence of depressive symptoms; however, patients recruited in the clinic had higher scores on the Geriatric Depression Scale compared with patients recruited from senior centers. Participants who interviewed in Spanish were less educated and less acculturated than those who interviewed in English. Overall, caregivers had higher mean S-TOFHLA scores and higher prevalence of adequate health literacy compared with patients. Further, caregivers recruited from senior centers compared with those recruited from the clinics were more likely to be older, less educated, and less acculturated. They also had lower scores on the Mini Mental State Exam, were more likely to have taken the interview in Spanish, and had lower health literacy compared with caregivers recruited from the clinics.

Table 1.

Characteristics and health literacy levels of Hispanic elderly patients and their caregivers, by recruitment site

| Clinic |

Senior center* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 70) M (SD) or n (%) | Caregivers (n = 70) M (SD) or n(%) | p value for difference between patients and caregivers | Patients (n = 104) M (SD) or n(%) | Caregivers (n = 104) M (SD) or n (%) | p value for difference between patients and caregivers | |

| Age, years (range = 30–96) | 75.5 (6.8) | 57.2 (14.5)a | <.0001 | 75.1 (6.1) | 69.7 (10.2)a | <.001 |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||||

| <65 | 0 (0) | 42 (60)b | <.001 | 0 (0) | 27 (25.9)b | <.001 |

| 65–70 | 16 (22.8) | 13 (18.6) | 28 (26.9) | 24 (23.1) | ||

| 71–80 | 38 (54.3) | 11 (22.5) | 51 (49.0) | 40 (38.5) | ||

| >80 | 16 (22.9) | 4 (5.7) | 25 (24.0) | 13 (12.5) | ||

| Male, n (%) | 27 (39.1)c | 17 (24.6) | .068 | 67 (64.4) | 24 (23.1)c | <.001 |

| Caregiver relationship, n (%) | ||||||

| Spouse/partner | 26 (37.1)d | — | 85 (81.7)d | — | ||

| Family member | 40 (57.1) | 9 (8.7) | ||||

| Hired caregiver | 4 (5.7) | 4 (3.9) | ||||

| Friend (unpaid) | 0 (0) | 6 (5.8) | ||||

| Education, years (range = 0–20) | ||||||

| Overall | 8.7 (4.5) | 12.5 (3.6)e | <.0001 | 8.6 (4.4) | 9.6 (3.8)f | .0849 |

| Spanish speakerf | 6.9 (4.7) | 11.5 (5.7) | .0138 | 4.6 (3.7) | 6.5 (4.0) | .0415 |

| English speakersg | 9.7 (4.1) | 12.8 (3.1) | <.0001 | 10.6 (3.4) | 11.0 (2.7) | .4204 |

| Education category, n (%) | ||||||

| Overall | ||||||

| Less than high school | 46 (65.7) | 17 (24.3)h | <.001 | 60 (57.7) | 51 (49.0)h | .419 |

| High school graduate | 12 (17.1) | 19 (27.1) | 27 (26.0) | 38 (36.5) | ||

| Some college | 8 (11.4) | 18 (25.7) | 14 (13.5) | 13 (12.5) | ||

| College graduate | 4 (5.7) | 16 (22.9) | 3 (2.9) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| Spanish speakers | ||||||

| Less than high school | 19 (76.0) | 5 (20.8) | .034 | 31 (91.2) | 26 (81.3) | .283 |

| High school graduate | 2 (8.0) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (8.8) | 4 (12.5) | ||

| Some college | 3 (12.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.2) | ||

| College graduate | 1 (4.0) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| English speakers | ||||||

| Less than high school | 27 (60.0) | 12 (20.7) | <.001 | 29 (41.4) | 25 (34.7) | .466 |

| High school graduate | 10 (22.2) | 18 (31.0) | 24 (34.3) | 34 (47.2) | ||

| Some college | 5 (11.1) | 17 (29.3) | 14 (20.0) | 11 (15.3) | ||

| College graduate | 0 (0) | 2 (2.8) | ||||

| Acculturation | 2.4 (1.0) | 3.1 (0.9)i | <.0001 | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.0)i | 1.00 |

| Acculturation level, n (%) | ||||||

| Strata 1 | 19 (27.1) | 5 (7.1)j | <.001 | 25 (24.0) | 23 (22.1)j | .214 |

| Strata 2 | 11 (15.7) | 9 (12.9) | 18 (17.3) | 27 (26.0) | ||

| Strata 3 | 34 (48.6) | 33 (47.1) | 51 (49.0) | 39 (37.5) | ||

| Strata 4 | 6 (8.6) | 23 (32.9) | 10 (9.6) | 15 (14.4) | ||

| Vision (20/X) | 38.3 (18.1) | 29.4 (13.8) | .0013 | 40.7 (20.1) | 30.6 (10.1) | <.0001 |

| Mini Mental State Exam score (range = 0–30) | 25.0 (3.5) | 28.6 (1.2)k | <.0001 | 25.0 (3.3) | 26.8 (3.0)k | .0001 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale score (range = 0–15) | 1.9 (2.3)l | 1.7 (2.8) | .6931 | 0.7 (1.2)l | 1.2 (2.0) | .0662 |

| Language S-TOFHLA administered (%) | ||||||

| English | 45 (64.3) | 58 (82.9)m | .013 | 70 (67.3) | 72 (69.2)m | .766 |

| Spanish | 25 (35.7) | 12 (17.1) | 34 (32.7) | 32 (30.8) | ||

| S-TOFHLA score (range = 0–36) | 16.1 (12.9) | 30.1 (7.8)n | <.0001 | 17.0 (11.3) | 21.8 (11.9)n | .0032 |

| Health literacy level, n (%) | ||||||

| Low (<23) | 45 (64.3) | 8 (11.4)o | <.001 | 68 (65.4) | 46 (44.2)o | .002 |

| Adequate (≥23) | 25 (35.7) | 62 (88.6) | 36 (34.6) | 58 (55.8) | ||

S-TOFHLA = Short Test of Functional Health Literacy Assessment.

*Differences in all patient and caregiver characteristics by recruitment site, clinic versus senior center, were tested using t test for continuous variables and chi-square statistic for categorical variables. If a significant difference was found, the p value is included in a footnote for the individual characteristic. If there is no footnote, no significant difference was found.

p value for age difference between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: <.0001.

p value for difference in distribution of age category between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: < .001.

p value for difference in proportion of male patients recruited from the clinic versus senior centers = .001.

p value for difference in distribution of caregiver relationship by recruitment site: <.001.

p value for difference in years of education between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: <.001.

Spanish speakers denotes those individuals who took the S-TOFHLA in Spanish; n = 37 at clinic sites and n = 66 at senior centers.

English speakers denotes those individuals who took the S-TOFHLA in English; n = 103 at clinic sites and n = 142 at senior centers.

p value for difference in distribution of age category between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: < .0001.

p value for difference in mean acculturation between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: <.001.

p value for difference in proportion of acculturation level between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers = .001.

p value for difference in Mini Mental State Exam score between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: < .0001.

p value for difference in Geriatric Depression Scale score between patients recruited from the clinic versus senior centers = .043.

p value for difference in proportion of caregivers taking the S-TOFHLA in Spanish versus English between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: < .0001.

p value for difference in S-TOFHLA score between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: < .0001.

p value for difference in proportion of low versus adequate health literacy between caregivers recruited from the clinic versus senior centers: < .001.

Table 2 documents the proportions of patients and caregivers with low health literacy overall and stratified by the language in which the patient completed the self-administered S-TOFHLA. Among the dyads, 52.3% (n = 91; 49 + 42) were composed of patients and caregivers with the same level of health literacy, whereas 47.7% (n = 83; 12 + 71) were composed of patients and caregivers who differed in their level of health literacy. The largest dyad category was the caregiver adequate-patient low health literacy group (n = 71; 41%), followed by the caregiver adequate-patient adequate health literacy group (n = 49; 28%), and the caregiver low-patient low health literacy group (n = 42; 24%). A small proportion (n = 12; 7%) of dyads consisted of the caregiver low-patient adequate health literacy group. Concordance of patient and caregiver health literacy levels within dyads was low for both continuous and categorical scores (Spearman's rho = 0.17 and kappa = 0.16, respectively).

Table 2.

Health literacy levels among older Hispanics and their caregivers

| Language of interview |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient and caregiver health literacy level | Total | Spanish | English |

| Patient adequate | n = 61 | n = 9 | n = 52 |

| Caregiver adequate, n (%) | 49 (80.3) | 9 (100.0) | 40 (76.9) |

| Caregiver low, n (%) | 12 (19.7) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (23.1) |

| Patient low | n = 113 | n = 50 | n = 63 |

| Caregiver adequate, n (%) | 71 (62.8) | 22 (44.0) | 49 (77.8) |

| Caregiver low, n (%) | 42 (37.2) | 28 (56.0) | 14 (22.2) |

| p | .017 | .002 | 1.00 |

Older Hispanic patients with low health literacy were somewhat more likely than those with adequate health literacy to also have low health literacy caregivers (37.2% [42/113] vs. 19.7% [12/61]). This appears to be attributable entirely to differences in caregivers' health literacy associated with their patients' interview language. A third (33.9%; n = 59) of the patients interviewed in Spanish; among these, 50 of 59 (84.7%) had low health literacy. Spanish-interview patients with low health literacy were much more likely to have caregivers with low health literacy compared with Spanish-interview patients with adequate health literacy (56.0% [28/50] vs. 0.0% [0/9]). In contrast, slightly more than half (54.8%, 63/115) of the patients who interviewed in English had low health literacy, but there was no association between their health literacy and that of their caregiver.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for potential correlates of low health literacy are shown in Table 3. In the adjusted analyses among patients, MMSE, education, and vision were significantly associated with the odds of having low health literacy. The adjusted odds ratios (low vs. adequate health literacy) were as follows: MMSE (OR = 0.68, CI [0.55, 0.83]), education category (OR = 0.15, CI [0.07, 0.31], and vision (OR = 1.04, CI [1.01, 1.07]). Higher MMSE score and education category were protective against low health literacy, whereas poorer vision was a risk factor for low health literacy. Each MMSE point increase was associated with 32% lower odds of low health literacy, while each increase in education stratum (indicating higher education) was associated with an 85% lower odds of low health literacy. Each decrease in visual acuity level (e.g., 20/30 vs. 20/20) was associated with 4% increased odds of low health literacy. Among caregivers, age, acculturation, MMSE, and recruitment site (clinic vs. senior center) were significantly associated with the odds of having low health literacy. The adjusted ORs (low vs. high health literacy) were as follows: age (OR = 3.16; CI [1.31, 7.25]), acculturation (OR = 0.45; CI [0.21, 0.93]), and MMSE (OR = 0.67; CI [0.54, 0.84]). After adjustment for all covariates in the model, recruitment site was not significantly associated with low health literacy. Older age was a risk factor for low health literacy, while higher MMSE scores and acculturation levels were protective against low health literacy. Each increase in age category was associated with greater than three times higher odds of low health literacy, while each increase in acculturation level was associated with 55% decreased odds of low health literacy; each point increase in MMSE was associated with 33% decreased odds of low health literacy.

Table 3.

Variables associated with low health literacy among patients and caregivers

| Patient (n = 174) OR (95% CI) | Caregiver (n = 174) OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate associationsa | ||

| Age categoryc | 1.83 (1.16–2.91)* | 2.44 (1.72–3.46)*** |

| Gender: Male versus female | 0.66 (0.35–1.24) | 1.84 (0.89–3.81) |

| Education categoryd | 0.13 (0.07–0.24)*** | 0.32 (0.20–0.52)*** |

| Acculturation stratum (1–4) | 0.37 (0.25–0.57)*** | 0.31 (0.21–0.47)*** |

| Interview language: Spanish versus English | 4.59 (2.06–10.20)*** | 6.06 (2.89–12.70)*** |

| Caregiver relationship: spouse/partner versus other | 0.44 (0.22–0.88)* | 5.88 (2.46–14.04)*** |

| Mini Mental State Exam (1-point increment) | 0.63 (0.54–0.74)*** | 0.58 (0.48–0.70)*** |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (1-point increment) | 1.09 (0.90–1.32) | 0.88 (0.74–1.04) |

| Vision (incremental decrease in visual acuity level) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06)*** | 1.03 (1.01–1.06)* |

| Recruitment site: clinic versus senior center | 1.05 (0.56–1.98) | 6.15 (2.68–14.12)*** |

| Multivariate associationsb | ||

| Age categoryc | 0.76 (0.24–2.41) | 3.16 (1.37–7.25)** |

| Education categoryd | 0.15 (0.07–0.31)*** | 0.84 (0.44–1.59) |

| Acculturation stratum (1–4) | 1.02 (0.43–2.40) | 0.45 (0.21–0.93)* |

| Interview language: Spanish versus English | 2.38 (0.46–12.44) | 2.58 (0.59–11.34) |

| Caregiver relationship: spouse versus other | 0.57 (0.17–1.92) | 1.55 (0.38–6.25) |

| Mini Mental State Exam (1-point increment) | 0.68 (0.55–0.83)*** | 0.67 (0.54–1.07)** |

| Vision (incremental decrease in visual acuity level) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07)** | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) |

| Recruitment site: clinic versus senior center | 1.62 (0.52–5.09) | 1.58 (0.53–4.70) |

OR = odds ratio.

Unadjusted; all associations are the unadjusted association between low health literacy and the individual variable listed.

Adjusted.

Age categories: <65, 65–70, 71–80, >80.

Education categories: less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduation.

p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

Discussion

Consistent with past studies (Baker et al., 2007; Federman, Sano, Wolf, Siu, & Halm, 2009; Kutner, 2006), we found a large prevalence (64.9%) of low health literacy within our sample of older Hispanic patients. Although caregivers were more likely to have adequate health literacy than their patients, the prevalence of low health literacy among caregivers was still 31%. Contrary to what we expected, there was no strong association between health literacy levels within dyads of older Hispanic patients and their caregivers in this sample. Factors associated with low health literacy in these analyses (i.e., cognitive impairment, age, lower education, poor vision, low acculturation) can be treated as signals that can alert health care professionals to possible low health literacy in their older Hispanic patients and their patients' caregivers.

The acculturation scale used in our study measured patients' and caregivers' relative use of English and Spanish in their daily lives. More frequent use of Spanish relative to English was associated with lower health literacy. This finding is consistent with prior studies showing that among U.S. Hispanics, informal (spoken) language is more important than formal (read or written) language; so that Hispanics who are fluent Spanish speakers may have little skill or experience in reading and/or writing Spanish (Espino, Lichtenstein, Palmer, & Hazuda, 2004). Further, in a study of California residents, including non-Hispanics who speak other languages, limited English proficiency was found to be associated with poorer comprehension of the medical situation, lower ability to understand labels, and more adverse medication reactions (Wilson, Chen, Grumbach, Wang, & Fernandez, 2005). In Hispanics, limited English proficiency has been shown to be associated with lower use of physician services (Derose & Baker, 2000). Although language of interview was associated with health literacy only in the univariate analyses and not in our multivariate analyses, speaking Spanish during the clinic visit may provide a useful, easily ascertained diagnostic clue that the older Hispanic patient and/or caregiver may have lower levels of education and acculturation—factors associated with low S-TOFHLA scores in our sample. Health care providers should attend to language spoken and appreciate that their patients may need both oral and written health information presented in the patients' native language in a clear, straightforward way that takes into account their education and acculturation levels. To more effectively meet communication needs, physicians can ask Hispanic patients and caregivers what language they use in their daily lives. For patients and caregivers who indicate that they use predominantly Spanish, it is important for clinicians to use more oral communication in Spanish with these individuals as an adjunct to written information. It has been noted that quality of care is compromised when patients with limited ability to communicate in English do not have access to interpreters, or when they use informal interpreters (Office of the Surgeon General and the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2006). Therefore, providers who lack Spanish fluency need access to skilled interpreters to relay health information in a clear, understandable way to Hispanic patients. Although data support that the use of professional interpreters improves health care delivery to limited English-speaking patients (Jacobs et al., 2001), these services may unfortunately not be widely available to practicing physicians and other care providers.

It is concerning that nearly a third of the caregivers in our study displayed low health literacy levels. A caregiver's low health literacy may negatively affect the health outcomes of their older patient, regardless of the patient's own health literacy level, as caregivers perform tasks that have a direct effect on the patient's health status, such as dispensing medications and assisting the patient in following physician instructions. As noted by Lindquist and colleagues (2010), who demonstrated that low health literacy was prevalent among paid caregivers of older patients, informal caregivers of older patients with low health literacy are likely unknowingly making errors, which could negatively affect health. The Surgeon General's Workshop on Health Literacy noted that low health literacy is not an individual deficit of any particular patient, but a systematic problem (Office of the Surgeon General and the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2010). Therefore, physicians and health care providers should be mindful of potentially low health literacy in the caregiver, and they should tailor advice and instructions carefully so as to provide information that is understandable to the caregiver and patient.

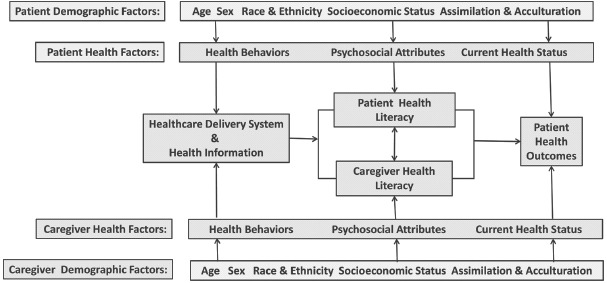

As shown in Figure 1, we have developed a conceptual framework to show the relationship between caregiver and patient health literacy and health outcomes during a clinical encounter. In this model, (a) patient and caregiver sociodemographic factors, (b) patient and caregiver health-related factors, and (c) health literacy factors (which include the patient and caregiver health literacy level, the health care delivery system itself, and the complexity of the health information to be conveyed) have relationships with each other as well as a direct effect on the patient's health outcomes.

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework for the influence of three major components on health outcome in the setting of the clinical encounter for both patients and caregivers: demographic factors, health literacy factors, and health status. Patient demographic factors include age, sex, ethnic group, and socioeconomic status. Acculturation and assimilation are also important demographic factors, encompassing language and culture. Health literacy factors include the health literacy of the patient and caregiver as well as the health care delivery itself and the health care information being conveyed. Patient health status includes disease, impairments, functional limitations, and disability. (Color figure available online.)

The conceptual model takes into account the influence on health literacy of acculturation as well as assimilation, particularly structural assimilation, or the degree to which members whose primary learning has been in another culture in which the language spoken is other than English have attained prerequisite English language skills and used them to interact with members of the broader society—that is, function effectively within the broader society (Hazuda, Stern, & Haffner, 1988). As noted by Frayne and colleagues in a study examining the inclusion of non-English patients in research (Frayne, Burns, & Hardt, 1996) one can anticipate intuitively that language differences between patients and providers affect communication and, thereby, patient outcomes such as compliance, education, and satisfaction. In an invited editorial comment on this study, we further noted that “… language and culture travel together. Language captures and shapes the meanings that constitute our understanding of ourselves and our world, and that set of meanings is culture” (Hazuda, 1996, p. 58).

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommends universal health literacy precautions to minimize the risk that patients will not understand the information they are given. These precautions ensure that systems are in place to promote better understanding of health care information for all patients, not just those that clinicians think need extra assistance (DeWalt et al., 2011). The high prevalence of low health literacy among caregivers highlights the need for clinicians to apply universal health literacy precautions not only to all patients but to all caregivers as well.

To potentially improve communication with caregivers, health professionals may want to use quick tools originally developed for patients. For example, the teach-back method requires the patient to verify understanding by repeating the information the provider just communicated to them to assure that this information was understood (Bertakis, 1977; Schillinger et al., 2003). Clinicians may also educate caregivers to use the “Ask me 3” questions when they receive information from health care providers (Miller et al., 2008). The “Ask Me 3” technique helps individuals take a more active role in their health care by asking their clinician three short questions that identify their main health problem, what they need to do about the problem, and why it is important to do this. These methods may help to determine whether an older patient, perhaps with cognitive impairment, fully understands the health information being conveyed. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of these communication tools among Spanish speakers. To assist older patients with visual impairment, which we showed also affects health literacy, the provider should consider screening for vision impairment, encourage use of corrective lenses, and provide written health information with large lettering to older patients.

This study had several limitations. First, although the S-TOFHLA has been validated in multiple groups (Nurss et al., 1998), it assesses only reading ability. Other aspects of communicating health information (e.g., oral and numeracy) were not assessed. However, written communication is frequently used in health care settings (e.g., registration forms, medication reconciliation lists, referrals, consent forms, and education materials); and, therefore, plays a role in adherence to medical treatment and health outcomes (Murphy et al., 2000). Second, the study sample was relatively small and not randomly selected. Nonetheless, this is the first study, to our knowledge, that examines levels of health literacy and concordance among Hispanic older patients and their caregivers. Therefore, it provides insights into areas requiring investigation in future studies: for example, (a) whether dyads with caregivers who have adequate health literacy are protective with regard to patients' health care utilization and outcomes, (b) whether patients are at increased risk of health problems when both the caregiver and the patient have low health literacy, and (c) which communication strategies are most effective with patients who speak only Spanish to assure that health information is understood and applied appropriately. Last, our population may not be representative of other Hispanic subgroups or of Mexican Americans in other regions of the United States.

In summary, we found a variety of health literacy levels among dyads composed of Hispanic older patients and their caregivers. Overall, however, both Hispanic elderly patients and their caregivers had a high prevalence of low health literacy.

Age, vision impairment, cognitive impairment, lower education, and lower acculturation were factors associated with low health literacy. These factors affect verbal and written communication among health care providers and their patients and caregivers. The current structure and characteristics of the U.S. health care system (lack of time and incentive, underdeveloped technology platforms to support communication, and provider/population mismatch across language and culture) does not support screening for and taking steps to address low health literacy by individual providers in their clinical practice settings (Office of the Surgeon General and the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2006). Our study suggests that providers should be attentive to possible low health literacy in the caregivers of their patients. We suggest that universal precautions should be used when in a clinical encounter with all patients and caregivers, and assume low health literacy for all individuals, until specific interactions provide evidence to the health care provider that the patient and/or caregiver has greater health care literacy. To improve the quality of care provided to older patients, policymakers should be mindful of low health literacy and its associated factors in patients and caregivers. Future longitudinal studies should examine the effect of caregiver health literacy on patient health outcomes.

References

- Aranda M. P., Knight B. G. The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:342–354. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. W., Gazmararian J. A., Sudano J., Patterson M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2000;55 doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.s368. S368-S374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. W., Williams M. V., Parker R., Gazmararian J. A., Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Education and Counseling. 1999;38:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. W., Wolf M. S., Feinglass J., Thompson J. A., Gazmararian J. A., Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1503–1509. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.14.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman N. D., Sheridan S. L., Donahue K. E., Halpern D. J., Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155:97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertakis K. D. The communication of information from physician to patient: A method for increasing patient retention and satisfaction. Journal of Family Practice. 1977;5:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan J. L., Loretta L. P. Understanding the impact of family caregiver cancer literacy on patient health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;71:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo O., Lantigua R. A., Shea S. Differences in functional status of Hispanic versus non-Hispanic White elders: Data from the medical expenditure panel survey. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12:342–361. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ath P., Katona P., Mullan E., Evans S., Katona C. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders. I: The acceptability and performance of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Family Practice. 1994;11:260–266. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose K. P., Baker D. W. Limited English proficiency and Latinos' use of physician services. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57:76–91. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt D. A., Broucksou K. A., Hawk V., Brach C., Hink A., Rudd R., Callahan L. Developing and testing the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Nursing Outlook. 2011;59:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino D. V., Lichtenstein M. J., Palmer R. F., Hazuda H. P. Ethnic differences in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores: Where you live makes a difference. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49:538–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49111.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino D. V., Lichtenstein M. J., Palmer R. F., Hazuda H. P. Evaluation of the Mini-Mental State Examination's internal consistency in a community-based sample of Mexican-American and European-American elders: Results from the San Antonio Longitudinal Study of Aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:822–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52226.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum On Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2010: Key indicators of well-being. Washington, DC: Author; 2010 July. [Google Scholar]

- Federman A. D., Sano M., Wolf M. S., Siu A. L., Halm E. A. Health literacy and cognitive performance in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:1475–1480. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02347.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M. F., Folstein S. E., McHugh P. R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayne S. M., Burns R. B., Hardt E. J., Rosen A. K., Moskowitz M. A. The exclusion of non-English-speaking persons from research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1996;11:39–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02603484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazuda H. P. Non-English-speaking patients a challenge to researchers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1996;11:58–59. doi: 10.1007/BF02603490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazuda H. P., Haffner S. M., Stern M. P., Eifler C. W. Effects of acculturation and socioeconomic status on obesity and diabetes in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Heart Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;128:1289–1301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazuda H. P., Stern M. P., Haffner S. M. Acculturation and assimilation among Mexican Americans: Scales and population-based data. Social Sciences Quarterly. 1988;69:687–705. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Promoting health literacy to encourage prevention and wellness: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs E. A., Lauderdale D. S., Meltzer D., Shorey J. M., Levinson W., Thisted R. A. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-English-proficient patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:468–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood B. R., Sterne J. Essential medical statistics. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kutner M. A. for the National Center for Education Statistics, United States Department of Education. The health literacy of America‘s adults: Results from the 2003 National assessment of adult literacy. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, United States Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist L. A., Jain N., Tam K., Martin G. J., Baker D. W. Inadequate health literacy among paid caregivers of seniors. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;26:474–479. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1596-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. J., Mary A. A., McClintock B., Matthew A. C., Corey D. D., Erin M. M. Promoting health communication between the community-dwelling well-elderly and pharmacists: The Ask Me 3 program. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2008;48:784–792. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P. W., Chesson A. L., Walker L., Arnold C. L., Chesson L. M. Comparing the effectiveness of video and written material for improving knowledge among sleep disorders clinic patients with limited literacy skills. Southern Medical Journal. 2000;93:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurss J., Parker R. M., Williams M. V., Baker D. W. Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (STOFHLA-English and STOFHLA-Spanish) Atlanta, GA: Center for the Study of Adult Literacy; 1998. Directions for administration and scoring and technical data. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General and the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Proceedings of the Surgeon General's Workshop on Improving Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: Office of the Surgeon General; 2006 September. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Orcos R., Salinero Fort M. A., Kazemzadeh Khajoui A., Vidal Aparicio S., de Dios del Valle R. Validation of 5 and 15 items spanish version of the geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in primary health care setting. Revista Clínica Española. 2007;207:559–562. doi: 10.1157/13111585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostchega Y., Harris T. B., Hirsch R., Parsons V. L., Kington R. The prevalence of functional limitations and disability in older persons in the US: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:1132–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan S. C., Parker R. M. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy(No. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1) Bethesda, MD: National Institue of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D., Piette J., Grumbach K., Wang F., Wilson C., Daher C. Closing the loop: Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon J., Trujillo A., Rosenbaum S., DeBuono B. Low health literacy: Implications for national health policy. Storrs: University of Connecticut, Department of Finance; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C. O., Hector M. G., Mohammed U. K., Kenneth M. L. Differences in amount of informal care received by non-Hispanic Whites and Latinos in a nationally representative sample of older americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E., Chen A. H., Grumbach K., Wang F., Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:800–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]