Summary

Ubiquitous noxious hydrophobic substances, such as hydrocarbons, pesticides and diverse industrial chemicals, stress biological systems and thereby affect their ability to mediate biosphere functions like element and energy cycling vital to biosphere health. Such chemically diverse compounds may have distinct toxic activities for cellular systems; they may also share a common mechanism of stress induction mediated by their hydrophobicity. We hypothesized that the stressful effects of, and cellular adaptations to, hydrophobic stressors operate at the level of water : macromolecule interactions. Here, we present evidence that: (i) hydrocarbons reduce structural interactions within and between cellular macromolecules, (ii) organic compatible solutes – metabolites that protect against osmotic and chaotrope‐induced stresses – ameliorate this effect, (iii) toxic hydrophobic substances induce a potent form of water stress in macromolecular and cellular systems, and (iv) the stress mechanism of, and cellular responses to, hydrophobic substances are remarkably similar to those associated with chaotrope‐induced water stress. These findings suggest that it may be possible to devise new interventions for microbial processes in both natural environments and industrial reactors to expand microbial tolerance of hydrophobic substances, and hence the biotic windows for such processes.

Introduction

The sustainability of Earth's biosphere is threatened by pollution loads of both persistent and non‐persistent hydrophobic substances. The degree of hydrophobicity of a compound is traditionally expressed as its partition coefficient in an octanol : water mixture, log Poctanol–water. Environmentally persistent compounds with a log P > 3, and non‐persistent molecules such as benzene (log P ≈ 2–3), can bioaccumulate along natural food chains (Kelly et al., 2007) and have adverse effects on animal and human health and reproduction (Lamm and Grunwald, 2006; Kelly et al., 2007). Moreover, many types of hydrophobic substances, such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene (the more soluble components of petroleum and oil), and pesticides such as gamma‐hexachlorocyclohexane (γ‐HCH or Lindane), can negatively influence the activities of microbial communities in impacted habitats (see Abraham et al., 2002; Roling et al., 2002; Olapade and Leff, 2003; Timmis, 2009). Microorganisms form the majority of the Earth's biomass (Whitman et al., 1998) and they collectively catalyse key processes in the element and energy cycles that maintain planetary health and biosphere function: decomposition of organic waste materials, the biogeochemical cycling of nutrients, soil formation, regulation of atmosphere composition and the degradation of pollutants.

The low solubility of hydrophobic substances limits their availability for catabolism by bacteria and other microbes (Quintero et al., 2005; Keane et al., 2008). However if the bioavailability of pollutants is increased (by surfactant addition or modifications in temperature), there is usually a concomitant increase in their inhibitory potency/lethality to the microbial cell (Bramwell and Laha, 2000). Toxicants such as toluene cause cross‐membrane proton gradients to break down and induce the upregulation of genes involved in toluene degradation and/or the synthesis of solvent extrusion pumps (and genes involved in increasing energy generation for these pumps) to remove the compound from the cell (Weber and de Bont, 1996; Kieboom et al., 1998; Ramos et al., 2002). Hydrophobic substances are well known for both their toxicity and their interference with the structural interactions of cellular macromolecules and lipid bilayers (see Sikkema et al., 1994; Fang et al., 2007; Duldhardt et al., 2010). However, there have been few studies in relation to a role for water in the stress mechanisms by which hydrophobic substances may inhibit cellular processes, the biological consequences for the microbial cell, and of the water‐stress responses they may induce. Here we have tested the hypothesis that diverse hydrophobic substances induce cellular stress via a common mechanism, namely by perturbation of the process by which water molecules facilitate structural, and hence functional interactions of cellular macromolecules.

Cells of the environmentally ubiquitous bacterium Pseudomonas putida, and two phylogenetically widespread enzymes, hexokinase and β‐galactosidase, were used as model systems to test this hypothesis. Pseudomonas putida is efficient in the catabolism and bioremediation of an extensive range of xenobiotics and other aromatics (Garmendia et al., 2001), due to a combination of its metabolic versatility and inherent tolerance of hydrophobic substances (Inoue and Horikoshi, 1989; Timmis, 2002); it has multiple uses in industrial biotechnologies, such as biocatalysis in two‐phase solvent systems, and was recently used as a model species to elucidate a new form of solute stress: chaotrope‐induced non‐osmotic water stress (Hallsworth et al., 2003a). In the present study, we analysed the responses of P. putida and the model enzymes to chemically diverse compounds with a range of log P values, from extremely hydrophobic species (e.g. trichlorobenzene) to those of a relatively hydrophilic nature, such as formamide. The data obtained suggested that indeed diverse hydrophobic substances inhibit the activities of macromolecules and cells through a common mechanism, that cells mount a generic response when exposed to them, and that water : macromolecule interactions are implicated in both the stress mechanism and cellular response. Furthermore, compatible solutes – such as glycerol – are protective against this type of stress. We suggest here that hydrophobic compounds induce a new type of water stress, which seems at first sight counter‐intuitive, but is consistent with the protective effect of compatible solutes.

Results and discussion

Inhibition of cellular activity by hydrophobic substances: chaotropicity versus log P

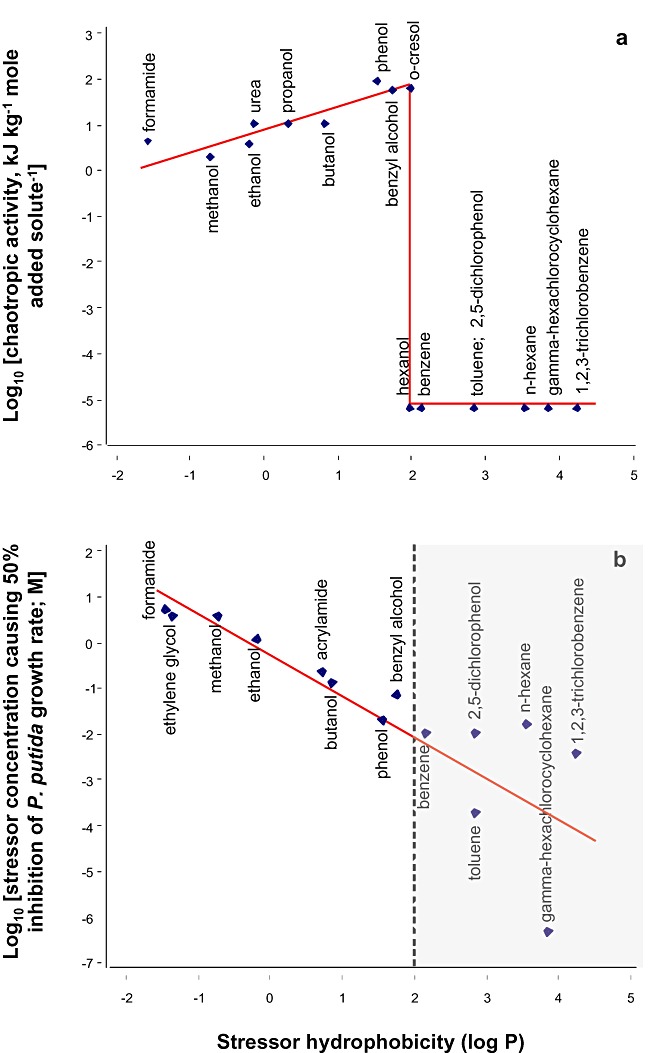

The physicochemical properties and biological activities of persistent (e.g. xylene, hexane, trichlorobenzene) and non‐persistent hydrophobic pollutants (e.g. benzene and toluene) were compared with lower log P substances such as phenol, formamide and ethanol. All compounds were studied at sub‐saturating concentrations and were therefore incorporated into media as solutes. The macromolecule‐disordering (chaotropic) activity of each solute was quantified according to its tendency to lower the gelation temperature of hydrophilic agar molecules (a technique that correlates with diverse observations in the field of cellular stress biology; see Hallsworth et al., 2003a; 2007) and plotted against hydrophobicity (log Poctanol–water; Fig. 1A). For substances with a log P ≤ 1.95, there was a direct relationship between chaotropicity and hydrophobicity. For substances with a log P higher than 1.95, no chaotropic activity was detected (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Activities of hydrophobic substances, and other environmentally relevant stressors, in macromolecular (A) and cellular systems (B) versus log Poctanol–water for (A) chaotropic solute activity – quantified using agar gelation as a model system – and (B) inhibitory activity against P. putida. Trend lines are shown in red, and the grey shaded area in (B) indicates the log P region for hydrophobic stressors. The values for chaotropic activity that were calculated from agar : stressor solutions are listed in Table S1; chaotropicity (±1.2 kJ kg−1; see Table S1) and growth‐rate values are means of three independent experiments, and these values were plotted on logarithmic scales.

Many chaotropic solutes hydrogen‐bond more weakly with water molecules than water molecules do with themselves (e.g. ethanol; see Ly et al., 2002), so have small hydration shells relative to non‐chaotropic compounds, such as kosmotropes. There is accordingly an inverse correlation between the polarity and chaotropicity of a compound: for substances that do not partition in the hydrophobic domains of macromolecular systems, hydrophobicity and chaotropicity are at this chemical level interconnected. However, at log P values > 1.95, hydrocarbons are insufficiently soluble to exert detectable chaotropic activity from within the aqueous phase of macromolecular systems. We formulated the hypothesis that environmental pollutants include two major categories of cellular stressor, namely those solutes that are ubiquitous and pervasive in the cellular milieu, are partitioned in the aqueous phase of all macromolecular systems, and induce cellular water stress via their chaotropic properties (Hallsworth et al., 2003a), and those that partition into the hydrophobic domains of macromolecules and lipid bilayers, thereby disordering their structures and thereby acting in a chaotropic manner.

In order to test this hypothesis we plotted the concentration of hydrophilic chaotropes and hydrophobic substances that inhibited the growth rate of P. putida by 50% relative to the control (no stressor present) versus stressor log P, to determine whether the qualitative distinction between the behaviour of hydrophilic versus hydrophobic stressors observed in Fig. 1A correlated with differences in growth‐rate inhibition (Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, there was a proportionality between inhibition of cell function and hydrophobicity, for stressors with a log P < 2 (see Fig. 1B), a result consistent with a study of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus stressed by chemically diverse aliphatic alcohols, including ethanol, butanol, octanol and decanol (Kabelitz et al., 2003). In contrast, the log P values of hydrophobic compounds did not correlate strongly with P. putida growth‐rate inhibition (see grey shaded region), and a low concentration (low‐mM range) terminated growth of bacterial cells (Fig. 1B). One difference between the agar (Fig. 1A) and bacterial assay systems (Fig. 1B; Kabelitz et al., 2003) is that agar is homogeneous and hydrophilic, so macromolecular interactions are primarily hydrophilic in nature, whereas cellular systems are heterogeneous with hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains, so undergo both hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions. In order to shed light on the differences in the results of Fig. 1A and B, we investigated the inhibitory activities of hydrocarbons on two well‐characterized, multi‐subunit enzyme systems, β‐galactosidase and hexokinase. In both systems, the hydrophobic effect is required to stabilize the secondary, tertiary and/or quaternary structure, but the hydrophobic effect is apparently more important for the structural stability, and therefore catalytic activity, of hexokinase. Hydrophobic substances with log P values > 1.95 exerted negligible inhibition of β‐galactosidase activity (Fig. 2A), which is consistent with their low solubility and inability to disorder hydrophilic macromolecule systems (Fig. 1A). In contrast the relatively hydrophilic, chaotropic, substances inhibited β‐galactosidase activity by 70–95% and the magnitude of this inhibition was proportional to their chaotropicity (Figs 1A and 2B). This implies that they did so via their disordering effect on the structure of β‐galactosidase, a result that is consistent with data obtained using other enzyme systems (Hallsworth et al., 2007). In order to shed light on the mechanism by which hydrophobic compounds inhibit cell function (Fig. 1B), we quantified the activity of the hexokinase‐based enzyme system in the presence of benzene, toluene, octanol, xylene and hexane (Fig. S1). These substances reduced hexokinase activity by up to 80%, which is consistent with their inhibitory effect on the cell (see Fig. 1B). In other words, these hydrocarbons inhibit the functionality of cellular systems via their interaction with hydrophobic domains.

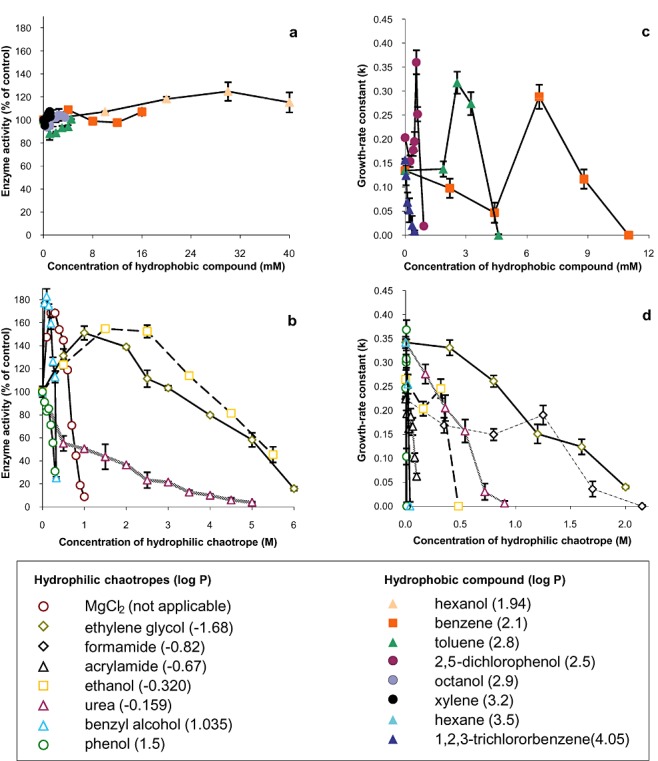

Figure 2.

Inhibition of (A and B) catalytic activity of the model enzyme β‐galactosidase, and (C and D) growth rate of P. putida, by hydrophobic substances and other environmentally relevant stressors: (A) β‐galactosidase activity in the presence of hydrophobic compounds or (B) hydrophilic chaotropes, (C) growth rate of P. putida in media containing hydrophobic compounds or (D) hydrophilic chaotropes. Enzyme assays were carried out independently in duplicate (β‐galactosidase) and P. putida stress tolerance assays were carried out in triplicate; plotted values are means, and standard deviations are shown.

We therefore quantified growth inhibition of P. putida cells over a range of concentrations of chemically diverse stressors, to establish whether the inhibition of microbial function hydrophobic substances correlates with the inhibition of macromolecule function (Fig. 2C and D; for kosmotropic stressors see Table S2). As reported previously for toluene (see Joo et al., 2000) some hydrocarbons promoted growth at low concentrations (see Fig. 2C); at very low sublethal levels diverse stress parameters are known to stimulate microbial growth rates (Brown, 1990). For both hydrophobic substances (Fig. 2C) and hydrophilic chaotropes (Fig. 2D), the concentrations at which inhibition of cellular activity occurred were of the same order of magnitude as those at which inhibition of enzyme activities occurred (Fig. 2B; Fig. S1). Hydrophobic substances were tolerated only up to 12 mM (Fig. 2C), whereas chaotropic and kosmotropic solutes were tolerated at concentrations of up to 2500 mM (see Fig. 2D; Table S2), depending on the compound. Furthermore, the stressor concentrations required to inhibit growth rates were proportional to stressor chaotropicity and/or log P. The results obtained suggest that any target‐specific toxic effects of these stressors on cells of P. putida are minimal and that, despite their distinct chemical properties and cellular partitioning tendencies, the inhibition of cellular activity by hydrophobic compounds and hydrophilic chaotropes occurs via a common mechanism. As both these classes of stressor are able to disorder macromolecular systems, and compatible solutes are known to protect against hydrophilic chaotropes, we formulated the hypothesis that compatible solutes would protect biological macromolecules against both classes of stressor.

Compatible solutes protect microbes exposed to hydrophobic substances

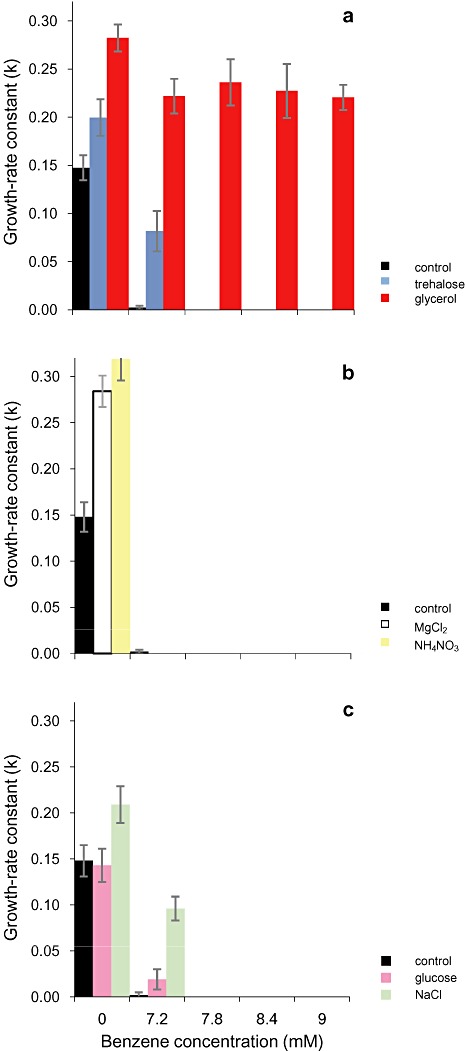

Microbial cells synthesize and accumulate low‐molecular‐weight hydrophilic compounds such as glycerol, mannitol, proline, betaine and trehalose that can protect their macromolecular apparatus under stressful conditions such as low water activity or extremes of temperature (see Brown, 1990). Compatible solutes such as glycerol and trehalose may sometimes be implicated in turgor control but frequently act as protectants of macromolecular structures independently of osmotic processes (see Brown, 1990); indeed microbial cells may even release compatible solutes into the extracellular mileu in order to protect both sides of the plasma membrane (see Eleutherio et al., 1993; Albertyn et al., 1994; Kets et al., 1996a). To test whether such compounds can reduce the inhibitory effects of hydrophobic substances in vivo we obtained exponential‐phase P. putida cells with high intracellular concentrations of glycerol or trehalose [up to 714 and 870 µg (1010 cells)−1 respectively] by culturing on a range of media (see Table 1); these concentrations were consistent with those reported previously, see Brown, 1990; Manzanera and colleagues, 2004. These cells were used to inoculate media containing benzene (up to 9 mM), a model hydrophobic stressor that is environmentally ubiquitous, industrially relevant, and can be metabolized to induce carcinogenic activity in mammals. Control (low‐compatible solute) cells – see Table 1– were virtually unable to grow under benzene stress (at or above a benzene concentration of 7.2 mM; Fig. 3A–C). In contrast, the cells containing high intracellular concentrations of glycerol retained a high growth‐rate (k ≥ 0.22) regardless of benzene concentration, and there was no apparent inhibition of cellular function even at 9 mM benzene (Fig. 3A). High‐trehalose cells were also more benzene‐tolerant than control cells, but were unable to grow at ≥ 7.8 mM benzene (Fig. 3A). The potent protective effect of glycerol did not correlate with the water activity or chaotropicity of the medium used to produce these cells because those obtained from cultures grown at low water activities (in media supplemented with MgCl2, glucose or NaCl) or those from chaotropic media (which had been supplemented with MgCl2 or NH4NO3) that contained only trace amounts of glycerol did not show benzene tolerance comparable to those from glycerol‐supplemented media (see Table 1; Fig. 3B and C). These data eliminate factors such as modified membrane composition as the determinants of stress tolerance (see also Hallsworth and Magan, 1995; Hallsworth et al., 2003b). This result is consistent with the results of parallel studies for the chaotropic stressor ethanol (Hallsworth et al., 2003b); furthermore the protective effect of glycerol was maintained throughout the period of growth‐rate assessment (i.e. through approximately nine cell divisions; data not shown). Cells were provided with a balanced C : N ratio in the medium (approximately 8:1 that is required for structural growth; Roels, 1983) so given that stressed cells expend energy to retain their compatible solutes (see Brown, 1990), the intracellular glycerol concentration of benzene‐stressed cells would have become diluted by a factor of nine. Previous studies of intracellular compatible solutes in fungal cells showed a powerful protective effect against ethanol in cells harvested from glycerol‐supplemented media as well as those obtained from KCl‐supplemented media even when the intracellular polyol content of the latter was 10 or 20 times lower than the former (Hallsworth et al., 2003b). Whereas glycerol, at high concentrations (≥ 4 M), can act as a powerful chaotrope (see Williams and Hallsworth, 2009; Chin et al., 2010) this compound is not chaotropic at lower concentrations and is well known for its protective properties (see Brown, 1990). We speculated that some compatible solutes may enable cellular function under benzene stress by reversing the disordering activities of this hydrocarbon (see Fig. 4). In order to test whether retention of metabolic activity in the presence of hydrophobic hydrocarbons was determined at the macromolecule structure–function level, we carried out activity assays for enzymes inhibited by benzene and hexane, using the hexokinase enzyme system. For comparison, we assayed β‐galactosidase that was inhibited by the hydrophilic chaotropes ethanol and MgCl2. In each case, enzyme assays (controls) were carried out at concentrations of stressors that inhibited catalytic activity between 60% and 90% relative to the optimum. Further assays were carried out over a range of concentrations of trehalose, mannitol, glycerol, betaine or proline, all of which occur naturally as protectants in cells of P. putida (Kets et al., 1996b), to see whether optimum enzyme activity could be restored.

Table 1.

Compatible‐solute content of P. putida cells during exponential growth on minimal mineral‐salt media supplemented with diverse solutes.a

| Added compound (concentration; M) | Water activity of mediab | Chao‐ or kosmotropic activity of media (kJ kg−1 mole−1)c | Intracellular concentration [µg (1010 cells)−1]d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | Mannitol | Trehalose | Betaine | |||

| None [control] | 0.998 | −0.95 | 2 | Trace | 20 | Trace |

| Trehalose (0.53)e | 0.984 | −6.3 | 4 | 11 | 870 | Trace |

| Glycerol (2.0)e | 0.951 | +1.3 | 714 | Trace | Trace | Trace |

| MgCl2 (0.26)f | 0.982 | +0.9 | Trace | Trace | Trace | Trace |

| NH4NO3 (0.36)f | 0.995 | +3.9 | Trace | 10 | Trace | Trace |

| Glucose (0.57)g | 0.986 | −0.2 | Trace | 30 | 60 | Trace |

| NaCl (0.60)g | 0.972 | −7.1 | Trace | 10 | Trace | Trace |

All values represent means of three independent analyses.

At 30°C.

Positive values indicate chaotropic activity; negative values indicate kosmotropic activity.

Trace indicates ≤ 1 µg (1010 cells)−1.

Compatible solutes.

Chaotropic stressors.

Kosmotropic compounds (that induce osmotic stress).

Figure 3.

Benzene tolerance of P. putida cells with diverse compatible‐solute contents after growth on media supplemented with glycerol, trehalose or solute stressors (see Table 1) for: (A) cells from high‐trehalose and high‐glycerol media, (B) cells from chaotropic (high‐MgCl2 and high‐NH4NO3) media and (C) cells from low‐water‐activity (high‐glucose or high‐NaCl) media. The stress tolerance assays were carried out in triplicate; plotted values are means and standard deviations are shown.

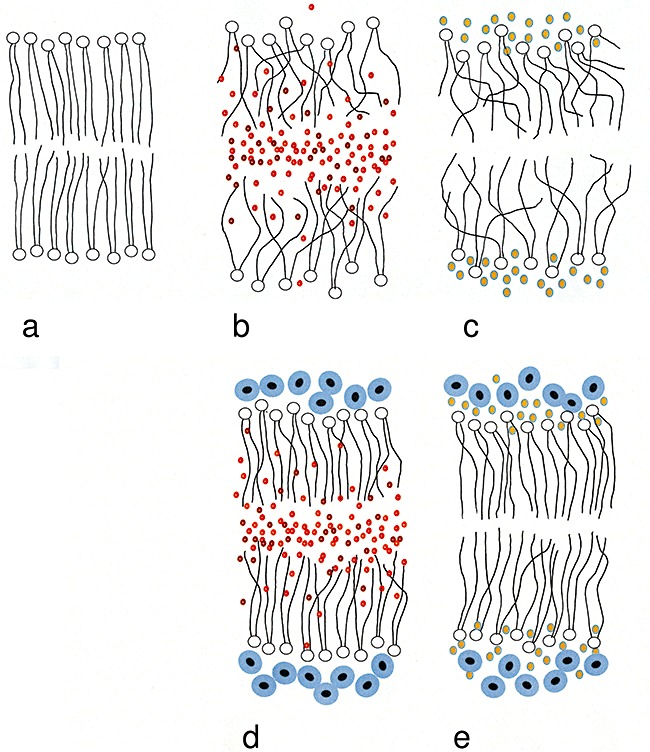

Figure 4.

Diagrammatic illustration of a lipid bilayer showing the locations of hydrophobic substances (e.g. benzene) and hydrophilic chaotropes (e.g. ethanol) that destabilize the structure of lipid bilayers, and the way in which compatible solutes (e.g. betaine) protect against this activity: (A) no added substance (unstressed membrane), (B) benzene‐stressed membrane, (C) ethanol‐stressed membrane, (D) membrane exposed to benzene and betaine and (E) membrane exposed to ethanol and betaine.

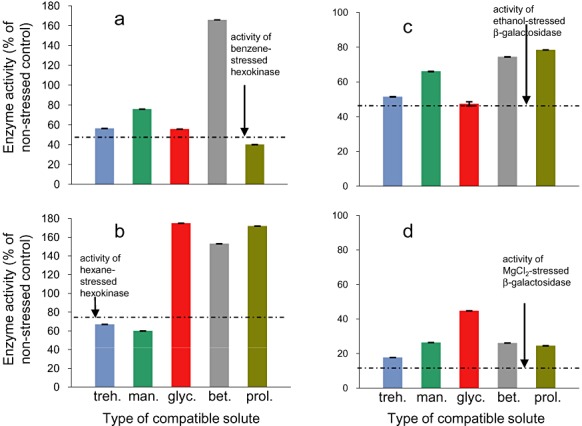

Generally, the effect of compatible solutes on enzyme activities was both stressor‐ and protectant‐specific, a phenomenon consistent with diverse studies of microbial stress biology (Fig. 5A–D; see Brown, 1990; Hallsworth and Magan, 1995; Hallsworth, 1998; Joo et al., 2000) and compatible solute : macromolecule interactions (e.g. Crowe et al., 1984; Arakawa and Timasheff, 1985). Glycerol reversed enzyme inhibition under hexane and MgCl2 stress (Fig. 5B and D), a result that is consistent with the observed protective effect of glycerol against benzene in vivo (Fig. 3A). Betaine was highly protective under benzene, hexane, ethanol and MgCl2 stress (Fig. 5A–D), a result that correlated with the known protective effect of betaine in vivo (see Brown, 1990; Jennings and Burke, 1990). Indeed, glycerol and betaine enhanced activity to beyond the level of the non‐stressed enzyme for benzene‐ and hexane‐stressed systems (Fig. 5A and B).

Figure 5.

Protection of stressor‐inhibited enzymes by diverse compatible solutes for: (A and B) a benzene‐inhibited (A) and a hexane‐inhibited (B) hexokinase‐pyruvate kinase‐lactate dehydrogenase reaction and (C and D) ethanol‐inhibited (C) and MgCl2‐inhibited (D) β‐galactosidase. All stressors were used to cause 60–90% inhibition of catalytic activity at the following concentrations: benzene 20.5 mM, hexane 123 µM, ethanol 5.2 M and MgCl2 0.97 M (see A–D). Compatible‐solute concentrations were: trehalose 5 mM, mannitol 300 mM, glycerol 2000 mM, betaine 1500 mM and proline 78 mM (A and B) and trehalose 62.5 mM, mannitol 75 mM, glycerol 150 mM, betaine 125 mM, proline 156 mM (C and D). All enzyme assays were carried out independently in triplicate (hexokinase assay) or duplicate (β‐galactosidase) and standard deviations are shown.

Trehalose reduced the inhibition caused by benzene (Fig. 5A) as well as the chaotropic substances ethanol (Fig. 5C), MgCl2 (Fig. 5D) and ethylene glycol (data not shown). In contrast, trehalose was inhibitory in hexane (Fig. 5B) and xylene assays (data now shown), as well as those of chaotropic stressors such as urea and benzyl alcohol (data not shown). This correlates with observations in cellular biology that trehalose protects cells against lower‐log P hydrocarbons such as benzene (Fig. 3A) and toluene (Joo et al., 2000) as well as specific chaotropes such as ethanol (see Mansure et al., 1994; Hallsworth, 1998). Generally, mannitol and proline showed greater protective activity than trehalose, depending on the stressor (Fig. 5A–D). The observation that protectants against water stress can protect macromolecular and cellular systems against inhibition by both hydrophilic chaotropes and hydrophobic hydrocarbons provides evidence of the common macromolecule‐disordering activities of each class of stressor (see Fig. 4), and that substances that are located in hydrophobic domains nevertheless impair the function of both enzymes and cellular systems via a water‐mediated mechanism (Fig. 4; see also McCammick et al., 2009). We therefore asked the question whether microbial cells exposed to diverse hydrophobic stressors exhibit a water stress response.

Commonality between cellular responses to hydrophobic hydrocarbons and hydrophilic chaotropes

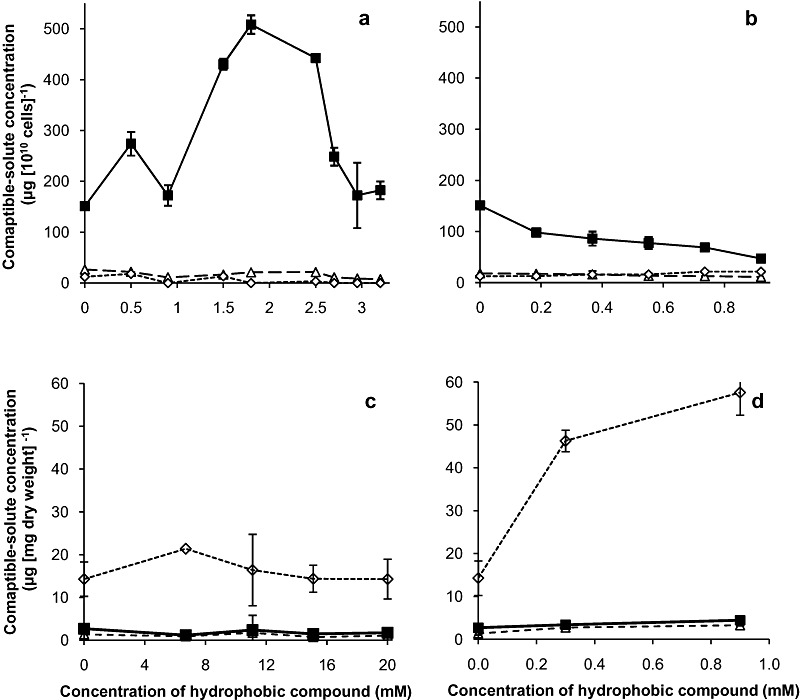

There are numerous studies of microbial activity in the presence of hydrophilic chaotropes that either correlate stressor tolerance with compatible‐solute concentration (e.g. Hallsworth, 1998; Hallsworth et al., 2003b), or demonstrate the upregulation of genes involved in compatible‐solute synthesis (e.g. Alexandre et al., 2001; Kurbatov et al., 2006; van Voorst et al., 2006; see also Table 2). We searched for evidence that compatible solutes protect diverse microbial species from stress induced by hydrophobic stressor and/or that such stressors (log P > 1.95) can upregulate the synthesis of intracellular compatible solutes. Surprisingly, we found a substantial number of studies that demonstrated a role for compatible solutes in hydrocarbon‐stressed cells for diverse bacterial species as well as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (for a selection of these see Table 2). We stressed cells of P. putida by culturing them in the presence of diverse hydrophobic stressors – benzene, toluene and 2,5‐dichlorophenol – over a range of concentrations, and harvested cells during the exponential growth phase to analyse compatible‐solute content (Fig. 6A and B). Intriguingly we only found one compatible solute, trehalose, that was synthesized and accumulated in response to toluene (Fig. 6A) but not benzene (data not shown) or 2,5‐dichlorophenol (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the accumulation of trehalose correlated with an unusually high toluene tolerance considering the high log P value of the latter (see Fig. 1B). Despite the comparable hydrophobicity of toluene and 2,5‐dichlorophenol, the trehalose‐protected cells were able to tolerate up to ≈ 4.5 mM toluene whereas the low‐trehalose cells in 2,5‐dichlorophenol‐supplemented media were unable to grow above 0.9 mM 2,5‐dichlorophenol (Fig. 2C). Generally, induction of compatible‐solute synthesis in response to turgor changes occurs at water activity values ≤ 0.985 (F.L. Alves and J.E. Hallsworth, unpubl. data) and toluene is therefore insufficiently soluble – by an order of magnitude – to generate an osmotic stress. The toluene‐induced accumulation of trehalose correlated with evidence that toluene upregulates genes involved in trehalose synthesis (e.g. Park et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Evidence for the role of compatible solutes and protein‐stabilization proteins in microbial cells that are adapting, or have adapted, to hydrophobic substances or hydrophilic chaotropes.a

| Area of stress metabolism | Hydrophobic substances | Hydrophilic chaotropes |

|---|---|---|

| Compatible solutes | In P. putida glycerol and trehalose enhance benzene tolerance (current study); trehalose enhances toluene tolerance. Toluene triggers trehalose synthesis and accumulation in P. putida and in Micrococcus sp. (Joo et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2006; Park et al., 2007; current study). Betaine and other amino acids protect microbial enzymes against diverse hydrophobic stressors (e.g. benzene and hexane; current study). Evidence for increased synthesis and transport of proline, glutamate and other amino acids under stress in P. putida (for toluene, xylene and DCP; Segura et al., 2005; Benndorf et al., 2006; Dominguez‐Cuevas et al., 2006), Burkholderia xenovorans (biphenyl; Denef et al., 2004) and in Escherichia coli (hexane; Hayashi et al., 2003)b and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (octanol; Fujita et al., 2004). Upregulation of AGT1 (which is involved in trehalose uptake) in S. cerevisiae in response to iso‐octane (Miura et al., 2000) | Trehalose enhances ethanol tolerance in E. coli and S. cerevisiae (Mansure et al., 1994; Hallsworth, 1998; Purvis et al., 2005). Ethanol‐inducedc upregulation of trehalose synthesis genes in S. cerevisiae (Alexandre et al., 2001; van Voorst et al., 2006). Glycerol and erythritol enhance ethanol tolerance in Aspergillus nidulans (Hallsworth et al., 2003b). Highest reported ethanol yield/tolerance (28% v/v) achieved in presence of proline (Thomas et al., 1994; see Hallsworth et al., 2007). Ectoine enhances phenol tolerance in Halomonas sp. (Maskow and Kleinsteuber, 2004). Phenol‐ and ethanol‐induced upregulation of genes involved in betaine, glutamate and proline synthesis and transport in P. putida and E. coli (Gonzalez et al., 2003; Kurbatov et al., 2006). Glycerol, trehalose, mannitol, betaine and proline protect microbial enzymes against MgCl2 stress (current study) |

| Protein stabilization | Upregulation of gene expression, increased synthesis and/or enhanced stress tolerance associated with diverse chaperonins, heat‐shock proteins and other protein‐stabilization proteins (e.g. CspA, DnaJ, DnaK, GroEL, GroES, GrpE, HtpX, IbpA, HtpG, HSIV, HSIU, trigger protein) in response to toluene and xylene in P. putida (Segura et al., 2005; Dominguez‐Cuevas et al., 2006; Volkers et al., 2006; Ballerstedt et al., 2007), benzene and hexane in E. coli (Hs1J, HtpX, IbpAB; Blom et al., 1992; Hayashi et al., 2003), biphenyl in B. xenovorans (Denef et al., 2004) and octanol and pentane in S. cerevisiae (see Fujita et al., 2004). (Similar responses are seen in mammalian cells in response to benzene and Lindane; e.g. Wu et al., 1998; Saradha et al., 2008) | Upregulation of gene expression, increased synthesis and/or enhanced stress tolerance associated with diverse chaperonins, heat‐shock proteins and other protein‐stabilization proteins (e.g. ClpB, DnaK, GroEL, GrpE, Hs1V, HtpG, IbpA, trigger protein) in response to ethanol, phenol and benzyl alcohol in P. putida (Hallsworth et al., 2003a; Santos et al., 2004; Tsirogianni et al., 2006) and other species (e.g. Bacillus subtilis; see Tam et al., 2006; S. cerevisiae on ethanol; see van Voorst et al., 2006 ). Overproduction of heat‐shock proteins enhanced tolerance to LiCl stress in S. cerevisiae (Imai and Yahara, 2000) and ethanol and butanol stress in Lactobacillus plantarum (Fiocco et al., 2007) |

All types of macromolecular structure and interaction can potentially be stabilized by compatible solutes.

Compatible solutes are required on both sides of the plasma membrane for effective protection (see Mansure et al., 1994).

Whereas pure ethanol is an organic solvent, at sub‐saturating concentrations ethanol acts as a solute in water (see Hallsworth, 1998).

Figure 6.

Intracellular compatible‐solute contents of exponentially growing cells of P. putida (A and B) in minimal mineral‐salt media (at 30°C; see Fig. 2C) supplemented with (A) toluene and (B) 2,5‐dichlorophenol; and those of A. penicillioides (C and D) on MYPiA+sucrose (1.64 M, at 15°C; see Fig. S2) medium supplemented with (C) benzene and (D) octanol over a range of concentrations. Compatible solutes were (◊) glycerol, (▵) mannitol and ( ) trehalose. Plotted values are means of triplicate experiments, and standard deviations are shown.

) trehalose. Plotted values are means of triplicate experiments, and standard deviations are shown.

To determine whether compatible‐solute synthesis under stress induced by specific hydrocarbons is unique to the bacterium P. putida we carried out a cross‐kingdom study to see whether a stress‐tolerant xerophile, the ascomycete fungus Aspergillus penicillioides that has some tolerance to benzene and octanol (for growth curves see Fig. S2), accumulates compatible solutes in response to these stressors (Fig. 6C and D). Studies of other eukaryotic microbes, such as S. cerevisiae, present evidence for enhanced synthesis and uptake of compatible solutes in response to hydrocarbons such as octanol and isooctane (see Miura et al., 2000; Fujita et al., 2004). In the current study cells of A. penicillioides did accumulate a compatible solute, namely glycerol, on octanol‐supplemented media (Fig. 6D) but not on benzene‐supplemented media (Fig. 6C). This suggests that, despite the low solubility of octanol, this compound may trigger the same stress response (via a high‐osmolarity glycerol response pathway signal transduction pathway) that is known to be triggered by osmotic stress (Furukawa et al., 2005). This gives rise to a number of scientifically intriguing questions – what is the mechanism by which this takes place; why do toluene and octanol trigger compatible‐solute synthesis/accumulation whereas benzene and 2,5‐dichlorophenol do not; how are phylogenetically diverse organisms genetically wired up to synthesize physicochemically distinct compatible solutes in response to hydrophobic stressors; and what are the different ecological benefits that trehalose and glycerol might confer?

Genes coding for production of chaperonins, heat‐shock proteins and other proteins involved in protein stabilization (e.g. DnaK, GroEL, GroES, GrpE, HtpG, HtpX, IbpA and trigger protein) can be upregulated by diverse hydrocarbons including benzene, toluene, xylene and hexane in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic species (see Table 2). Furthermore such proteins have been correlated with enhanced tolerance to these stressors (see Table 2). A comparable range of microbes have been shown to upregulate protein stabilization proteins in response to hydrophilic chaotropes, including LiCl, ethanol, butanol, phenol and benzyl alcohol (see Table 2) and have, in numerous studies, been associated with enhanced tolerance to the stressor. Other microbial responses to these two classes of stressor include the stabilization of nucleic acid structures, gene‐regulating processes and membrane structures; there is a strong resemblance between the cellular responses to hydrophobic substances and hydrophilic chaotropes regardless of microbial taxon or specificity of the chemical compound (e.g. Mizushima et al., 1993; Dogan et al., 2006; Radniecki et al., 2008; Trautwein et al., 2008).

Compatible solutes may also protect nucleic acid structures and those of proteins involved in nucleic acid synthesis, repair and binding (Xie and Timasheff, 1997); it has been suggested that nucleic acids represent the failure point of microbial cells under other extreme conditions (see Pitt, 1975). The empirical evidence for the upregulation of diverse macromolecule‐protection systems is remarkably similar for both hydrophilic chaotropes and hydrophobic substances (Figs 3 and 5; Table 2; Hallsworth et al., 2003a). There are a number of qualitative differences between these two classes of stressor: their chemistry and behaviour (see Fig. 1A); their location within macromolecular structures (see Figs 2A and B and 4; Fig. S1); the inhibitory concentrations differ by orders of magnitude (Fig. 2A–D; Fig. S1) implying that macromolecular stress induced by hydrophobic compounds is more potent; the mechanisms by which macromolecular structures may be inhibited (Fig. 4); and the types of macromolecular structures that are affected (Fig. 2A and B; Fig. S1). However the structural changes induced by hydrophobic substances and chaotropic solutes may, in essence, be the same (see Fig. 4), a notion supported by the remarkable similarity between microbial response to each class of stressor (Table 2).

Collectively these data, and the data presented in the current study, support the hypothesis that hydrophobic substances in the microbial cell can act as chaotropic stressors that disorder macromolecular systems by not only weakening hydrophobic forces, but ultimately by reducing water : macromolecule interactions. The data presented in the current study (see also Table 2) indicate that hydrophobic hydrocarbons are not primarily cellular toxicants that have target‐specific modes‐of‐action (see Trinci and Ryley, 1984), but that they inhibit microbial systems via physicochemical interventions in the interactions of diverse cellular macromolecules (Sikkema et al., 1995), and that their stressful effects and the corresponding cellular adaptations/responses can be mediated by water (see also McCammick et al., 2009).

A previously uncharacterized form of water stress

Water stress has conventionally been thought of as the cellular consequence of either excess or insufficient water, e.g. hypo‐osmotic stress, hyper‐osmotic stress, matric stress, desiccation. However, macromolecular systems interact with water at multiple levels (see Brown, 1990; Daniel et al., 2004), and these interactions can be modified with adverse consequences to the cellular system as demonstrated in studies of chaotrope‐induced microbial stress (Hallsworth, 1998; Hallsworth et al., 2003a). Chaotropic ions induce cellular water stress (see Hallsworth et al., 2007) and may do so by shedding their water of hydration as they move into the hydrophobic domains of macromolecules/membranes from where they destabilize the structure due, in part at least, to their physical bulk (see Sachs and Woolf, 2003). Recent studies of glycerol‐induced water stress suggest that, at high concentrations, glycerol may have a lower affinity to hydrogen bond with water so it may partition into hydrophobic domains in a similar way to chaotropic ions or hydrophobic compounds (Chen et al., 2009; Williams and Hallsworth, 2009). Hydrocarbon‐induced water stress may be described as a form of non‐osmotic water stress that results from the chaotropicity of substances that preferentially partition into hydrophobic domains of the cell (see also McCammick et al., 2009). In this way, hydrophobic compounds that are typically not in contact with cellular water induce water stress by proxy and this is remarkably similar to that induced by chaotropic ions as well as, it seems, by excessive glycerol concentrations. Furthermore, cellular compatible solutes that counter hydrocarbon‐induced water stress primarily protect the system by proxy, i.e. without direct contact with the hydrocarbon stressor (see Fig. 4D).

Regardless of their chemical nature, stressors that destabilize macromolecular structures will ultimately have an adverse impact on most, if not all, of the biochemical reactions and interactions within the cell, and can potentially impact on any (all) metabolic process(es). Furthermore, a significant proportion of cellular metabolites are chaotropic or hydrophobic (e.g. ethanol, urea, phenol, catechol, benzene) and the possibility that microbial cells are subject to collateral damage from intracellular substances has not yet been investigated. In a study of Rhodococcus erythropolis, cells adapted to toluene were found to have increased tolerance to ethanol (de Carvalho et al., 2007), and in studies of diverse bacterial species cells adapted to hydrophilic chaotropes or hydrophobic substances have increased tolerance to heat stress (e.g. Flahaut et al., 1996; Vercellone‐Smith and Herson, 1997; Park et al., 2001; Periago et al., 2002; Capozzi et al., 2009). Whereas cross‐talk between microbial responses to different stresses is well known, it has not been mechanistically well understood. The data presented in the current study exemplify how diverse stresses are linked through macromolecular structures and their interactions, and via the role that compatible solutes play in this aspect of cellular activity. This understanding may facilitate knowledge‐based interventions in microbial processes such as bioremediation of polluted soils or biotransformations in two‐phase solvent systems where cellular stress currently limits microbial productivity.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strain, media and culture conditions

Pseudomonas putida strain KT2440 (DSMZ 6125) was obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) and maintained in a liquid minimal mineral‐salt medium with glucose as the sole carbon substrate and NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen substrate (pH 7.4; for details see Hartmans et al., 1989). All cultures were grown in 50 ml of medium in Supelco serum bottles (100 ml) sealed with aluminum caps with PTFE/butyl septa to avoid volatilization of added stressors (see below), and incubated in a shaking incubator (New Brunswick Innova 44, set at 120 rpm) at 30°C.

Addition of stressors to media

For all stress experiments, stressors were added after media were autoclaved and been allowed to cool, and prior to inoculation. The chaotropic stressors were: MgCl2, formamide, ethylene glycol, methanol, ethanol, urea, propanol, acrylamide, butanol, phenol, benzyl alcohol and cresol. For hydrophobic stressors (hexanol, benzene, 2,5‐dichlorophenol, toluene, octanol, xylene, hexane, gamma‐hexachlorocyclohexane and 1,2,3‐trichlorobenzene) each substance was chilled to 15°C prior to addition to media in order to minimize the risk of volatilization, and the serum bottles were immediately sealed with a cap. Inoculations were carried out through the caps' septa using disposable syringes (1 ml) fitted with a needles. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Quantification of water activity, and chaotropic activity, of media

The water‐activity values of media were determined at 30°C (unless otherwise stated) using a Novasina IC II water activity machine fitted an alcohol‐resistant humidity sensor and eVALC alcohol filter (Novasina, Pfäffikon, Switzerland) as described previously (see Hallsworth and Nomura, 1999). This equipment was calibrated using saturated salt solutions of known water activity (Winston and Bates, 1960) and values were determined three times using replicate solutions made up on separate occasions; variation between replicates was within ±0.003 aw. The chaotropic activity of stressors was quantified based on changes in the gelation temperature of agar solutions as described previously (Hallsworth et al., 2003a); variation between replicate measurements was within ±0.3°C.

Determination of P. putida growth rates

All media were inoculated using cell suspensions from exponentially growing pre‐cultures (0.4–0.6 ml) to give a turbidity reading between 0.1 and 0.15 at 560 nm. Samples were taken at hourly or 2‐hourly intervals (depending on growth rate) and the growth‐rate constant (k) during the exponential growth phase was calculated from the slopes of the growth curves. Calculations of stressor concentrations that inhibited P. putida growth rate by 50% were made by comparing growth‐rate data with that for control media (no stressor added).

P. putida stressor dose–response experiments

To establish the stress tolerance of P. putida to each stressor, cells were grown over a range of concentrations of chemically diverse stressors (see Brown, 1990; Hallsworth et al., 1998; Hallsworth et al., 2003a) at 30°C; details of inoculation and incubation are described above. Control cultures were incubated in the minimal mineral‐salt medium (no stressor added) under the same conditions. Growth rates were calculated as described above, and the growth‐rate constant values obtained were used to plot dose–response curves.

Manipulation of compatible‐solute phenotype of P. putida

Cells of P. putida were inoculated into diverse media in order to obtain cells that accumulated compatible solutes; as described previously for other microbial species (see Hallsworth and Magan, 1995; Hallsworth et al., 2003b). Cultures were grown in minimal mineral‐salt medium (control) or a medium supplemented with a compatible solute (either 0.53 M trehalose or 2 M glycerol), a chaotropic salt (0.26 M MgCl2 or 0.36 M NH4NO3), or a kosmotropic stressor (0.57 M glucose or 0.6 M NaCl). The concentration of each added substance was selected because it caused a 75% inhibition of P. putida growth rate at 30°C relative to the control (data not shown). Cells were harvested during mid‐exponential phase (turbidity560 ≈ 0.4–0.5) and used immediately either to test for stress tolerance (see below), or for compatible‐solute analysis (see below).

Analysis of intracellular compatible solutes from P. putida

Upon harvesting (see above), the turbidity of cultures were recorded and converted to cell number using a standard curve. Cells were centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 min at 4°C, resuspended in a harvesting solution with a composition identical to minimal mineral‐salt medium (no glucose or NH4Cl added) for control cells. The harvesting solutions for other cells were supplemented with NaCl to give water activity values consistent with each medium (see Table 1). In each case the harvesting solutions were kept on ice prior to the resuspension of cells. All cell suspensions were washed by decanting the supernatant and resuspending again in the same harvesting solution followed by a repeated centrifugation. The supernatants were decanted and the pellets of P. putida cells were immediately frozen at −20°C and stored at this temperature overnight prior to compatible‐solute extraction. Pellets were then defrosted by adding 1 ml of deionized, reverse‐osmosis (18 MΩ‐cm) water and sonicated (for 120 s at an amplitude of 15 µm), placed in a boiling water bath (5.5 min) and filtered as described previously (Hallsworth and Magan, 1997). Polyols and trehalose were analysed by ICS‐3000 Dionex Ion Chromatography System (Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, California, USA) fitted with a CarboPac™ MA1 plus guard column (Dionex), and quantified by pulsed electrochemical detection as described previously (Hallsworth and Magan, 1997). Amino acids and amino acid derivatives were analysed on the same system fitted with a AminoPac® PA10 plus guard column (Dionex), and also quantified by pulsed electrochemical detection. NMR was used for betaine analyses as described by Graham and colleagues (2009). All analyses were performed in triplicate using cultures harvested from independent experiments.

Impact of compatible‐solute phenotype on P. putida stress tolerance

Low‐compatible‐solute cells (from control media), high‐trehalose cells (from trehalose‐supplemented media) and high‐glycerol cells (from glycerol‐supplemented media; see Table 1) were assayed for tolerance to benzene. For comparison, chaotropically stressed cells (from MgCl2‐ and NH4NO3‐supplemented media) and cells from low‐water‐activity (glucose‐ and NaCl‐supplemented) media were assayed in the same experiment. Cells cultured at low water activity or under chaotrope‐induced stress were included for comparison to eliminate the possibility that observed phenotypic differences may have correlated with other adaptations to high‐solute media other than compatible‐solute accumulation (see also Hallsworth and Magan, 1995). Exponentially growing cells from each medium (with known intracellular compatible‐solute contents) were harvested as described above were immediately added to a range of minimal mineral‐salt media containing either no benzene or 7.2, 7.8, 8.4 or 9 mM benzene and incubated at 30°C (see above). Growth rates were recorded hourly and growth‐rate constants calculated as described above.

β‐Galactosidase functional activity assay

Escherichia coliβ‐galactosidase [Product code; G‐2513; Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, USA; supplied as a suspension in 1.7 M (NH4)2SO4, 10 mM Tris buffer salts and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.3] assays were carried out in a total reaction volume of 3 ml at 37°C. Each reaction contained 47 mM MOPS‐KOH (pH 7.3), 1 mM MgCl2, 1.1 mM 2‐nitrophenyl β‐d‐galactopyranoside. Stressors and/or compatible solutes were added as required (see Results and discussion). Cuvettes were immediately sealed with Parafilm (to prevent evaporation of volatile stressors), mixed by inverting, and placed in the thermoelectrically controlled heating block of the Cecil E2501 spectrophotometer (Milton Technical Centre, Cambridge, England) for 2 min to equilibrate. Reactions were initiated by addition of 0.255 units of β‐galactosidase to the cuvette. The absorbance was monitored at 410 nm at 30‐s intervals over a period of 10–15 min.

Hexokinase functional activity assay

Saccharomyces cerevisiae hexokinase (Type F‐300, lyophilized powder; Sigma‐Aldrich). The assay was carried out in a volume of 900 µl and each reaction contained 20.3 mM Hepes‐KOH, pH 7.4, 5 mM glucose, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, 133 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM NADH, 0.2 mM PEP, 0.2 mM MgCl2 and 1.5 units of lactate dehydrogenase/pyruvate kinase (P0294; Sigma‐Aldrich). Stressors and/or compatible solutes were added as required. Cuvettes were sealed with Parafilm, inverted to mix and placed in the thermoelectrically controlled heating block of a spectrophotometer (see above) for 10 min at 25°C. The NADH‐utilization assay was initiated by the addition of hexokinase (9 µg ml−1; approximately 1 unit) and monitored at 340 nm at 30 s intervals over a period of 10 min. All measurements were made in triplicate.

Compatible‐solute response of A. penicillioides to hydrophobic compounds

The xerophile A. penicillioides (strain FRR 2179) was obtained from Food Research Ryde, Australia and maintained at 15°C on Malt‐Extract, Yeast‐Extract Phosphate Agar [MYPiA; 1% Malt‐Extract w/v (Oxoid, UK), 1% Yeast‐Extract w/v (Oxoid, UK), 0.3% Agar w/v (Acros, USA), 0.1% K2HPO4 w/v] supplemented with 1.64 M sucrose (0.955 aw at 15°C). Benzene and octanol that had been stored at 15°C were added to the MYPiA (which remained in a semi‐liquid state) at this temperature. Cellulose discs (9 cm diameter; A.A. Packaging, Preston, UK) were placed in each Petri plate, on top of the media and fungal plugs were inoculated in the centre of each (see Hallsworth et al., 2003b). Sections of mycelium (∼1 cm2) were dissected from the periphery of each culture (avoiding mycelium that had borne spores), washed and lyophilized (see Hallsworth and Magan, 1997), and compatible solutes were extracted and analysed as described above.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for useful discussions with Giuseppe Albano (Edinburgh University, UK), Virendra S. Gomase (Patil University, India), Allen Y. Mswaka (Queen's University Belfast), Mary Palfreyman (Outwood Grange College, UK) and Kenneth N. Timmis (Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, Germany). This project was carried out within the research programme of the Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation which is part of the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, the EU‐funded MIFRIEND and LINDANE projects, and a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council‐funded project (UK; Grant No. BBF0034711) which is part of the P. putida Systems Biology of Microorganisms project (PSYSMO).

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig. S1. Inhibition of catalytic activity of a model enzyme, hexokinase, in the presence of hydrophobic substances. Enzyme assays were carried out independently in triplicate; plotted values are means, and standard deviations are shown.

Fig. S2. Inhibition of growth rates (15°C) of four xerophilic fungi: Aspergillus penicillioides FRR 2179 (◆), Eurotium amstelodami FRR 2792 (▲), JH06THH (●) and JH06GBM (△) by the hydrophobic stressors (A) benzene and (B) octanol. All treatments were carried out in triplicate, and standard deviations are shown.

Table S1. Chaotropic activity of chemically diverse stressors calculated from agar : stressor solutions.

Table S2. Inhibitory concentrations of kosmotropic stressors for Pseudomonas putida KT2440.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Abraham W.R., Nogales B., Golyshin P.N., Pieper D.H., Timmis K.N. Polychlorinated biphenyl‐degrading microbial communities in soils and sediments. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:246–253. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertyn J., Hohmann S., Thevelein J.M., Prior B.A. GPD1, which encodes glycerol‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase, is essential for growth under osmotic‐stress in Saccharomyces‐cerevisiae, and its expression is regulated by high‐osmolarity glycerol response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4135–4144. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre H., Ansanay‐Galeote V., Dequin S., Blondin B. Global gene expression during short‐term ethanol stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2001;498:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa T., Timasheff S.N. The stabilization of proteins by osmolytes. Biophys J. 1985;47:411–414. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83932-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerstedt H., Volkers R.J.M., Mars A.E., Hallsworth J.E., Santos V.A.M., Puchalka J. Genomotyping of Pseudomonas putida strains using P. putida KT2440‐based high‐density DNA microarrays: implications for transcriptomics studies. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:1133–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0914-z. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benndorf D., Thiersch M., Loffhagen N., Kunath C., Harms H. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 responds specifically to chlorophenoxy herbicides and their initial metabolites. Proteomics. 2006;6:3319–3329. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom A., Harder W., Matin A. Unique and overlapping pollutant stress proteins of Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:331–334. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.331-334.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell D.A.P., Laha S. Effects of surfactant addition on the biomineralization and microbial toxicity of phenathrene. Biodegradation. 2000;4:263–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1011121603049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A.D. Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho C.C.C.R., Fatal V., Alves S.S., Da Fonseca M.M.R. Adaptation of Rhodococcus erythropolis cells to high concentrations of toluene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:1423–1430. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi V., Fiocco D., Amodio M.L., Gallone A., Spano G. Bacterial stressors in minimally processed food. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10:3076–3105. doi: 10.3390/ijms10073076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Li W.Z., Song Y.C., Yang J. Hydrogen bonding analysis of glycerol aqueous solutions: a molecular dynamics simulation study. J Mol Liq. 2009;146:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chin J.P., Megaw J., Magill C.L., Nowotarski K., Williams J.P., Bhaganna P. Solutes determine the temperature windows for microbial survival and growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7835–7840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000557107. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe J.H., Crowe L.M., Chapman D. Preservation of membranes in anhydrobiotic organisms – the role of trehalose. Science. 1984;223:701–703. doi: 10.1126/science.223.4637.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel R.M., Finney J.L., Stoneham M. The molecular basis of life: is life possible without water? A discussion meeting held at the Royal Society, London, UK, 3–4 December 2003. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1141–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Denef V.J., Park J., Tsoi T.V., Rouillard J.M., Zhang H., Wibbenmeyer J.A. Biphenyl and benzoate metabolism in a genomic context: outlining genome‐wide metabolic networks in Burkholderia xenovorans LB400. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4961–4970. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4961-4970.2004. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan I., Pagilla K.R., Webster D.A., Stark B.C. Expression of Vitreoscilla haemoglobin in Gordonia amarae enhances biosurfactant production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;33:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s10295-006-0097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez‐Cuevas P., Gonzalez‐Pastor J.E., Marques S., Ramos J.L., De Lorenzo V. Transcriptional tradeoff between metabolic and stress–response programs in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 cells exposed to toluene. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11981–11991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duldhardt I., Gaebel J., Chrzanowski L., Nijenhuis I., Härtig C., Schauer F., Heipieper H.J. Adaptation of anaerobically grown Thauera aromaticaGeobacter sulfurreducens and Desulfococcus multivorans to organic solvents on the level of membrane fatty acid composition. Microb Biotechnol. 2010;3:201–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleutherio E.C.A., Dearaujo P.S., Panek A.D. Role of the trehalose carrier in dehydration resistance of Saccharomyces‐cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1156:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(93)90040-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J.S., Lyon D.Y., Wiesner M.R., Dong J., Alvarez P.J.J. Effect of fullerene water suspension on bacterial phospholipids and membrane phase behaviour. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:2636–2642. doi: 10.1021/es062181w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiocco D., Capozzi V., Goffin P., Hols P., Spano G. Improved adaptation to heat, cold, and solvent tolerance in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;77:909–915. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flahaut S., Benachour A., Giard J.C., Boutibonnes P., Auffray Y. Defence against lethal treatments and de novo protein synthesis induced by NaCl in Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 19433. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s002030050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K., Matsuyama A., Kobayashi Y., Iwahashi H. Comprehensive gene expression analysis of the response to straight‐chain alcohols in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using cDNA microarray. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:57–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K., Hoshi Y., Maeda T., Nakajima T., Abe K. Aspergillus nidulans HOG pathway is activated only by two‐component signaling pathway in response to osmotic stress. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1246–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmendia J., Devos D., Valencia A., De Lorenzo V. Á la carte transcriptional regulators: unlocking responses of the prokaryotic enhancer‐binding protein XylR to non‐natural effectors. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:47–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R., Tao H., Purvis J.E., York S.W., Shanmugam K.T., Ingram L.O. Gene array‐based identification of changes that contribute to ethanol tolerance in ethanologenic Escherichia coli: comparison of KO11 (parent) to LY01 (resistant mutant) Biotechnol Prog. 2003;19:612–623. doi: 10.1021/bp025658q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S.F., Amiques E., Migaud M., Browne R.A. Application of NMR based metabolomics for mapping metabolite variation in European wheat. Metabolomics. 2009;5:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E. Ethanol‐induced water stress in yeast. J Ferment Bioeng. 1998;85:125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E., Magan N. Manipulation of intracellular glycerol and erythritol enhances germination of conidia at low water availability. Microbiology. 1995;141:1109–1115. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-5-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E., Magan N. A rapid HPLC protocol for detection of polyols and trehalose. J Microbiol Methods. 1997;29:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E., Nomura Y. A simple method to determine the water activity of ethanol‐containing samples. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;62:242–245. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990120)62:2<242::aid-bit15>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E., Nomura Y., Iwahara M. Ethanol‐induced water stress and fungal growth. J Ferment Bioeng. 1998;86:451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E., Heim S., Timmis K.N. Chaotropic solutes cause water stress in Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2003a;5:1270–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2003.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E., Prior B.A., Nomura Y., Iwahara M., Timmis K.N. Compatible solutes protect against chaotrope (ethanol)‐induced, nonosmotic water stress. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003b;69:7032–7034. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7032-7034.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallsworth J.E., Yakimov M.M., Golyshin P.N., Gillion J.L.M., D'Auria G., Alves F.D.L. Limits of life in MgCl2‐containing environments: chaotropicity defines the window. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:801–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01212.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmans S., Smits J.P., Van Der Werf M.J., Volkering F., De Bont J.A.M. Metabolism of styrene oxide and 2‐phenylethanol in the styrene‐degrading Xanthobacter strain 124X. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2850–2855. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2850-2855.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S., Aono R., Hanai T., Mori H., Kobayashi T., Honda H. Analysis of organic solvent tolerance in Escherichia coli using gene expression profiles from DNA microarrays. J Biosci Bioeng. 2003;95:379–383. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(03)80071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai J., Yahara I. Role of HSP90 in salt stress tolerance via stabilization and regulation of calcineurin. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9262–9270. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9262-9270.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A., Horikoshi K. A Pseudomonas thrives in high‐concentrations of toluene. Nature. 1989;338:264–266. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings D.H., Burke R.M. Compatible solutes – the mycological dimension and their role as physiological buffering agents. New Phytol. 1990;116:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Joo W.H., Shin Y.S., Lee Y., Park S.M., Jeong Y.K., Seo J.Y., Park J.U. Intracellular changes of trehalose content in toluene tolerant Pseudomonas sp. BCNU 171 after exposure to toluene. Biotechnol Lett. 2000;22:1021–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Kabelitz N., Santos P.M., Heipieper H.J. Effect of aliphatic alcohols on growth and degree of saturation of membrane lipids in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;220:223–227. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane A., Lau P.C.K., Ghoshal S. Use of a whole‐cell biosensor to assess the bioavailability enhancement of aromatic hydrocarbon compounds by nonionic surfactants. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99:86–98. doi: 10.1002/bit.21524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B.C., Ikonomou M.G., Blair J.D., Morin A.E., Gobas F.A.P.C. Food web‐specific biomagnification of persistent organic pollutants. Science. 2007;317:236–239. doi: 10.1126/science.1138275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kets E.P.W., De Bont J.A.M., Heipieper H.J. Physiological response of Pseudomonas putida S12 subjected to reduced water activity. FEMS Microbiol Letts. 1996a;139:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kets E.P.W., Galinski E.A., De Wit M., De Bont J.A.M., Heipieper H.J. Mannitol, a novel bacterial compatible solute in Pseudomonas putida S12. J Bacteriol. 1996b;178:6665–6670. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6665-6670.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieboom J., Dennis J.J., De Bont J.A.M., Zylstra G.J. Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux pump involved in Pseudomonas putida S12 solvent tolerance. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:85–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurbatov L., Albrecht D., Herrmann H., Petruschka L. Analysis of the proteome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 grown on different sources of carbon and energy. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:466–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm S.H., Grunwald H.W. Benzene exposure and hematotoxicity. Science. 2006;312:998. doi: 10.1126/science.312.5776.998b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly H.V., Block D.E., Longo M.L. Interfacial tension effect of ethanol on lipid bilayer rigidity, stability, and area/molecule: a micropipette aspiration approach. Langmuir. 2002;18:8988–8995. [Google Scholar]

- McCammick E.M., Gomase V.S., Timson D.J., McGenity T.J., Hallsworth J.E. Water‐hydrophobic compound interactions with the microbial cell. In: Timmis K.N., editor. Springer; 2009. pp. 1451–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Mansure J.J.C., Panek A.D., Crowe L.M., Crowe J.H. Trehalose inhibits ethanol effects on intact yeast‐cells and liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1191:309–316. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanera M., Vilchez S., Tunnacliffe A. High survival and stability rates of Escherichia coli dried in hydroxyectoine. FEMS Microbiol Letts. 2004;233:347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskow T., Kleinsteuber S. Carbon and energy fluxes during haloadaptation of Halomonas sp. EF11 growing on phenol. Extremophiles. 2004;8:133–141. doi: 10.1007/s00792-003-0372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura S., Zou W., Ueda M., Tanaka A. Screening of genes in Isooctane tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by using mRNA differential display. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:4883–4889. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.11.4883-4889.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima T., Natori S., Sekimizu K. Relaxation of supercoiled DNA associated with induction of heat shock proteins in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00279523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olapade O.A., Leff L.G. The effect of toluene on the microbial community of a river in Northeastern Ohio, USA. J Freshw Ecol. 2003;18:465–477. [Google Scholar]

- Park S.H., Oh K.H., Kim C.K. Adaptive and cross‐protective responses of Pseudomonas sp. DJ‐12 to several aromatics and other stress shocks. Curr Microbiol. 2001;43:176–181. doi: 10.1007/s002840010283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.C., Bae Y.U., Cho S.D., Kim S.A., Moon J.Y., Ha K.C. Toluene‐induced accumulation of trehalose by Pseudomonas sp BCNU 106 through expression of otsA and otsB homologues. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2007;1:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.02036.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periago P.M., Van Schaik W., Abee T., Wouters J.A. Identification of proteins involved in the heat stress response of Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3486–3495. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3486-3495.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt J.I. Xerophilic fungi and the spoilage of foods of plant origin. In: Duckworth R.B., editor. 1st. Academic Press; 1975. pp. 273–307. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis J.E., Yomano L.P., Ingram L.O. Enhanced trehalose production improves growth of Escherichia coli under osmotic stress. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3761–3769. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3761-3769.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero J.C., Moreira M.T., Feijoo G., Lema J.M. Effect of surfactants on the soil desorption of hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) isomers and their anaerobic biodegradation. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2005;80:1005–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Radniecki T.S., Dolan M.E., Semprini L. Physiological and transcriptional responses of Nitrosomonas europaea to toluene and benzene inhibition. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:4093–4098. doi: 10.1021/es702623s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos J.L., Duque E., Gallegos M.T., Godoy P., Gonzalez M.I.R., Rojas A. Mechanisms of solvent tolerance in gram‐negative bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:743–768. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.161038. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roels J.A. Elsevier Biomedical Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Roling W.F.M., Milner M.G., Jones D.M., Lee K., Daniel F., Swannell R.J.P., Head I.M. Robust hydrocarbon degradation and dynamics of bacterial communities during nutrient‐enhanced oil spill bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:5537–5548. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5537-5548.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J.N., Woolf T.B. Understanding the Hofmeister effect in interactions between chaotropic anions and lipid bilayers: molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8742–8743. doi: 10.1021/ja0355729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos P.M., Benndorf D., Sa‐Correia I. Insights into Pseudomonas putida KT2440 response to phenol‐induced stress by quantitative proteomics. Proteomics. 2004;4:2640–2652. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saradha B., Vaithinathan S., Mathur P.P. Single exposure to low dose of lindane causes transient decrease in testicular steroidogenesis in adult male Wistar rats. Toxicology. 2008;244:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura A., Godoy P., Van Dillewijn P., Hurtado A., Arroyo A., Santacruz S., Ramos J.L. Proteomic analysis reveals the participation of energy‐ and stress‐related proteins in the response of Pseudomonas putida DOT‐T1E to toluene. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5937–5945. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.5937-5945.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema J., De Bont J.A.M., Poolman B. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8022–8028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema J., De Bont J.A.M., Poolman B. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:201–222. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.201-222.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam L.T., Eymann C., Albrecht D., Sietmann R., Schauer F., Hecker M., Antelmann H. Differential gene expression in response to phenol and catechol reveals different metabolic activities for the degradation of aromatic compounds in Bacillus subtilis. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1408–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K.C., Hynes S.H., Ingledew W.M. Effects of particulate materials and osmoprotectants on very‐high‐gravity Eehanolic fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1519–1524. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1519-1524.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmis K.N. Pseudomonas putida: a cosmopolitan opportunist par excellence. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:779–781. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmis K.N., editor. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein K., Kuhner G., Wohlbrand L., Halder T., Kuchta K., Steinbuchnel A., Rabus R. Solvent stress response of the denitrifying bacterium ‘Aromatoleum aromaticum’ strain EbN1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:2267–2274. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02381-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinci A.P.J., Ryley J.F., editors. Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirogianni E., Aivaliotis M., Papasotiriou D.G., Karas M., Tsiotis G. Identification of inducible protein complexes in the phenol degrader Pseudomonas sp. strain phDV1 by blue native gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Amino Acids. 2006;30:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercellone‐Smith P., Herson D.S. Toluene elicits a carbon starvation response in Pseudomonas putida mt‐2 containing the TOL plasmid pWW0. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1925–1932. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1925-1932.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkers R.J.M., De Jong A.L., Hulst A.G., Van Baar B.L.M., De Bont J.A.M., Wery J. Chemostat‐based proteomic analysis of toluene‐affected Pseudomonas putida S12. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1674–1679. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorst F., Houghton‐Larsen J., Jonson L., Kielland‐Brandt M.C., Brandt A. Genome‐wide identification of genes required for growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae under ethanol stress. Yeast. 2006;23:351–359. doi: 10.1002/yea.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber F.J., De Bont J.A.M. Adaptation mechanisms of microorganisms to the toxic effects of organic solvents on membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1286:225–245. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(96)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman W.H., Coleman D.C., Wiebe W.J. Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6578–6583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.P., Hallsworth J.E. Limits of life in hostile environments; no limits to biosphere function? Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:3292–3308. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston P.W., Bates D. Saturated solutions for control of humidity in biological research. Ecology. 1960;41:232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.C., Yuan Y., Wu Y., He H.Z., Zhang G.G., Tanguary R.M. Presence of antibodies to heat stress proteins in workers exposed to benzene and in patients with benzene poisoning. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:161–167. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0161:poaths>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie G.F., Timasheff S.N. The thermodynamic mechanism of protein stabilization of trehalose. Biophys Chem. 1997;64:25–43. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(96)02222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Yuan Q.P., Gao H.L., Ma R.Y. Production of trehalose by permeabilized Micrococcus QS412 cells. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2006;43:137–141. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Inhibition of catalytic activity of a model enzyme, hexokinase, in the presence of hydrophobic substances. Enzyme assays were carried out independently in triplicate; plotted values are means, and standard deviations are shown.

Fig. S2. Inhibition of growth rates (15°C) of four xerophilic fungi: Aspergillus penicillioides FRR 2179 (◆), Eurotium amstelodami FRR 2792 (▲), JH06THH (●) and JH06GBM (△) by the hydrophobic stressors (A) benzene and (B) octanol. All treatments were carried out in triplicate, and standard deviations are shown.

Table S1. Chaotropic activity of chemically diverse stressors calculated from agar : stressor solutions.

Table S2. Inhibitory concentrations of kosmotropic stressors for Pseudomonas putida KT2440.