Summary

Penicillins and cephalosporins are β‐lactam antibiotics widely used in human medicine. The biosynthesis of these compounds starts by the condensation of the amino acids l‐α‐aminoadipic acid, l‐cysteine and l‐valine to form the tripeptide δ‐l‐α‐aminoadipyl‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine catalysed by the non‐ribosomal peptide ‘ACV synthetase’. Subsequently, this tripeptide is cyclized to isopenicillin N that in Penicillium is converted to hydrophobic penicillins, e.g. benzylpenicillin. In Acremonium and in streptomycetes, isopenicillin N is later isomerized to penicillin N and finally converted to cephalosporin. Expression of genes of the penicillin (pcbAB, pcbC, pendDE) and cephalosporin clusters (pcbAB, pcbC, cefD1, cefD2, cefEF, cefG) is controlled by pleitropic regulators including LaeA, a methylase involved in heterochromatin rearrangement. The enzymes catalysing the last two steps of penicillin biosynthesis (phenylacetyl‐CoA ligase and isopenicillin N acyltransferase) are located in microbodies, as shown by immunoelectron microscopy and microbodies proteome analyses. Similarly, the Acremonium two‐component CefD1–CefD2 epimerization system is also located in microbodies. This compartmentalization implies intracellular transport of isopenicillin N (in the penicillin pathway) or isopenicillin N and penicillin N in the cephalosporin route. Two transporters of the MFS family cefT and cefM are involved in transport of intermediates and/or secretion of cephalosporins. However, there is no known transporter of benzylpenicillin despite its large production in industrial strains.

Introduction: the structure of β‐lactams

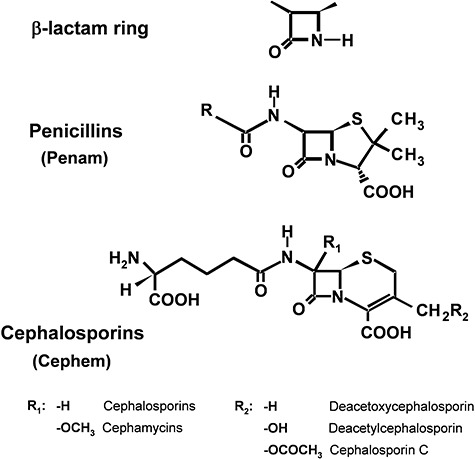

β‐Lactams, like many other secondary metabolites, have unusual chemical structures. All β‐lactams contain a four‐membered β‐lactam ring closed by an amide bond (Fig. 1). Penicillins contain a bicyclic ‘penam’ nucleus formed by fused β‐lactam and thiazolidine rings and an acyl side‐chain bound to the amino group at C‐6. They are produced by a few Penicillium and Aspergillus species (Aharonowitz et al., 1992). Recently penicillins have been found to be produced by a few other deuteromycetes (Laich et al., 1999; 2002; 2003). A second β‐lactam compound, cephalosporin C, produced by the fungi Acremonium chrysogenum, Paecilomyces persicinus and Kallichroma tethys (Kim et al., 2003) and some other deuteromycetes, contains the cephem nucleus (a six‐membered dihydrothiazine ring fused to the β‐lactam ring) (Fig. 1). Cephalosporin C has a d‐α‐aminoadipyl side‐chain attached to the C‐7 amino group, which is identical to that of hydrophilic penicillin N but differs from those of hydrophobic penicillins. Penicillins and cephalosporins are of great clinical interest as inhibitors of peptidoglycan biosynthesis in bacteria.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the β‐lactam ring, the penicillins (penam nucleus) and cephalosporins (cephem nucleus). Different penicillins contain distinct hydrophobic or hydrophilic side‐chains (R). The R1 and R2 groups of cephalosporins or cephamycins are indicated below the structure of cephalosporin.

Two groups of modified cephalosporins, the cephamycins and the cephabacins, are produced, respectively, by various Gram‐positive actinomycetes and some Gram‐negative bacteria (Aharonowitz et al., 1992). In the cephamycins, the cephem nucleus contains, in addition to the α‐aminoadipyl side‐chain, a methoxy group at C‐7; this group renders the cephamycin structure insensitive to hydrolysis by most β‐lactamases (Liras et al., 1998).

All these β‐lactam compounds (penicillins, cephalosporins, cephamycins and cephabacins) share a common mode of action and are synthesized from similar precursors by pathways with some steps in common.

Penicillin, cephalosporin and cephamycin biosynthetic pathways

A brief description of the biochemical pathways leading to classical β‐lactam antibiotic biosynthesis is made here. More detailed information on the specific steps are given in other review articles (Aharonowitz et al., 1992; Brakhage, 1998; Demain et al., 1998; Martín et al., 1999; Liras and Martín, 2009).

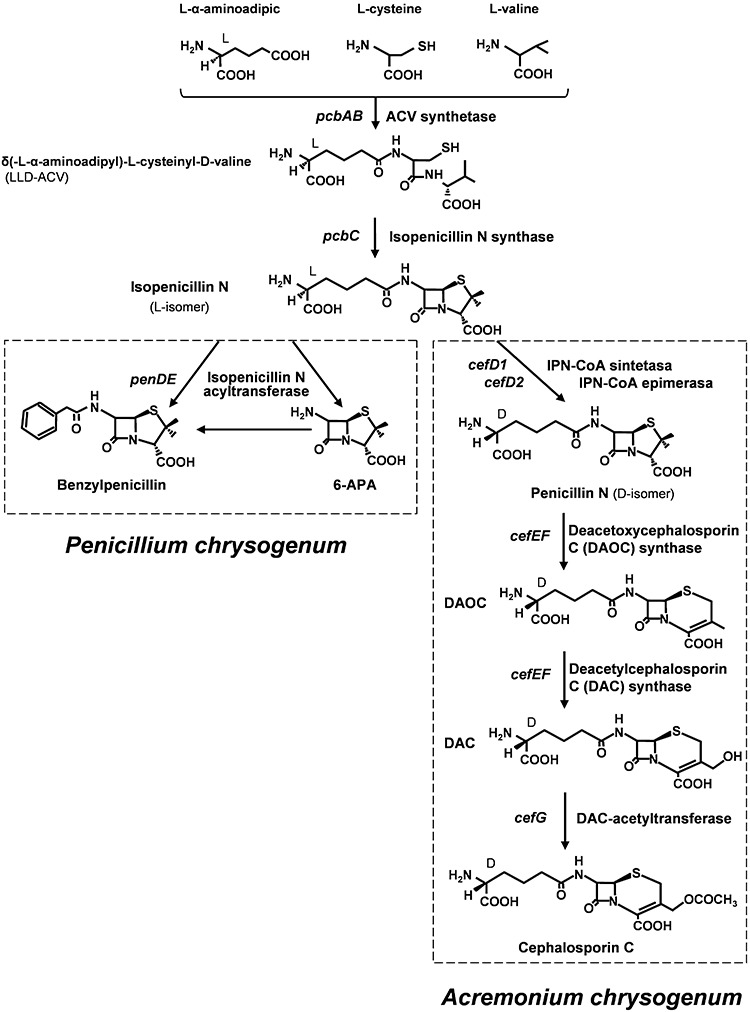

The biosynthesis of the β‐lactam compounds proceeds through a series of sequential reactions including the formation of a linear tripeptide intermediate and cyclization of the tripeptide to form the penam nucleus (so‐called ‘early biosynthetic steps’), conversion of the penam to the cephem nucleus by ring expansion (‘intermediate steps’) and ‘late (decoration) steps’ (Fig. 2) involving modifications of the β‐lactam nucleus.

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic pathways of benzylpenicillin and cephalosporin in Penicillium chrysogenum (left) and Acremonium chrysogenum (right) respectively. The first two steps (upper part of the figure) are common to both pathways. The l‐ or d‐configuration of the α‐aminoadipic side‐chains in each molecule is indicated by L or D on carbon 1 of this amino acid.

Three amino acids, l‐α‐aminoadipic acid, l‐cysteine and l‐valine, are the precursors of the basic structure of all the classical β‐lactam antibiotics; l‐valine and l‐cysteine are common amino acids but l‐α‐aminoadipic acid is a non‐proteinogenic amino acid and is formed by a specific pathway related to lysine biosynthesis. In bacteria‐producing β‐lactams, lysine is converted into α‐aminoadipic acid semialdehyde by lysine‐6‐aminotransferase (LAT) and this semialdehyde is oxidized to α‐aminoadipic acid by a piperideine‐6‐carboxylic acid dehydrogenase (P6C‐DH) (Coque et al., 1991; de la Fuente et al., 1997).

In fungi, α‐aminoadipic acid is an intermediate of the lysine biosynthesis pathway. In addition, lysine is catabolized to α‐aminoadipic acid in Penicillium chrysogenum (i) by an ω‐aminotransferase, encoded by the oat1 gene, which is induced by lysine (Martín de Valmaseda et al., 2005), and (ii) by a reversal of the lysine biosynthesis pathway catalysed by the enzymes saccharopine dehydrogenase/saccharopine reductase (Naranjo et al., 2001; Martín de Valmaseda et al., 2005).

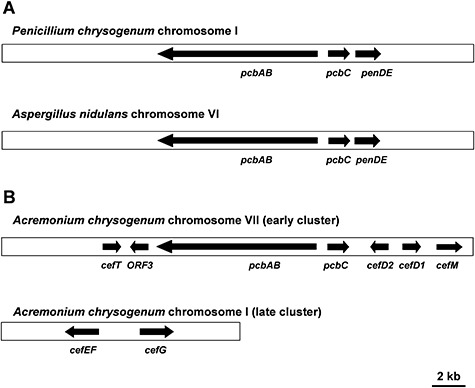

Two early enzymatic steps are common to all the classical β‐lactam producers, resulting in the formation of isopenicillin N (IPN), the first compound in the pathway with antibiotic activity. The first enzyme of the pathway is the ACV synthetase (ACVS), a non‐ribosomal peptide synthetase. The ACV synthetases are very large multifunctional proteins (Mr in the order of 420 kDa) encoded by intron‐free genes of 11 kb named pcbAB (Díez et al., 1990; Gutiérrez et al., 1991) which occur in the fungal and bacterial penicillin and cephalosporin (and cephamycin) clusters (Fig. 3). This enzyme sequentially activates the three substrates with ATP to form aminoacyl‐adenylates, binds them to the enzyme as thioesters, epimerizes the l‐valine to d‐valine, links together the three amino acids to form the peptide l‐δ(α‐aminoadipyl)‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine (hereafter named ACV) and, finally, releases this tripeptide from the enzyme by the action of an internal thioesterase activity. The ACV synthetases have three well conserved domains that activate each of the three amino acids respectively (Zhang and Demain, 1992; Aharonowitz et al., 1993; Martín, 2000a).

Figure 3.

A. Penicillin gene clusters in Penicillium chrysogenum and Aspergillus nidulans. B. Cephalosporin gene clusters in Acremonium chrysogenum. The ‘early cluster’ contains seven genes encoding the biosynthetic steps up to penicillin N and the MFS transporters, and the ‘late cluster’ contains the two genes converting penicillin N to cephalosporin C (see text).

The second enzyme in the pathway is the IPN synthase (IPNS, cyclase) encoded by the pcbC gene. The IPN synthases are intermolecular dioxygenases that require Fe2+, molecular oxygen and ascorbate. They remove four hydrogen atoms from the ACV tripeptide forming the bicyclic structure (penam nucleus) of IPN. The cyclase of P. chrysogenum has been crystallized showing a bread roll‐like structure (Roach et al., 1995; 1997).

In addition to the pcbAB and pcbC genes common to filamentous fungi and bacteria, the producers of hydrophobic penicillins (i.e. Penicillium, Aspergillus) contain a third gene in the penicillin cluster, named penDE, of eukaryotic origin (it contains three introns at difference of pcbAB and pcbC that are of bacterial origin) which encodes an IPN acyltransferase (IAT). This enzyme hydrolyses the α‐aminoadipic side‐chain of IPN and introduces an acyl molecule activated as its acyl‐CoA derivative to produce hydrophobic penicillins (e.g. benzylpenicillin). This gene is not present in cephalosporin C‐ or cephamycin‐producing microorganisms.

In addition to these key enzymes, other enzymes are also required for penicillin biosynthesis, such as the aryl‐CoA ligases, which activate the side‐chain aromatic acid (Lamas‐Maceiras et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007) and the phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) (Baldwin et al., 1991a; Lambalot et al., 1996), which activates the non‐ribosomal ACV tripeptide synthase (the first enzyme of the pathway).

Isopenicillin N is converted to its d‐isomer (penicillin N) in all the cephalosporin and cephamycin producers. Purification of the A. chrysogenum so‐called ‘IPN epimerase’ proved to be difficult and unreliable. In 2002 a breakthrough in our understanding of cephalosporin formation occurred when it was reported that the epimerization reaction was different in eukaryotic and prokaryotic microorganisms. The epimerization of IPN in A. chrysogenum is encoded by two linked genes, cefD1–cefD2, located in the ‘early’ cephalosporin gene cluster. The first gene, cefD1, has four introns and encodes a 71 kDa protein with similarity to fatty acid acyl‐CoA synthetases. In bacteria, epimerization of IPN to penicillin N is catalysed by a classical pyridoxal‐phosphate‐dependent epimerase. The second gene, cefD2, contains one intron and encodes a protein homologous to α‐methyl‐acyl‐CoA racemases of eukaryotic origin. Disruption of either of these ORFs results in a lack of cephalosporin C production, loss of IPN epimerase activity and accumulation of IPN in the culture (Ullán et al., 2002a). The proposed conversion includes three biochemical steps: CefD1 converts IPN into isopenicillinyl N‐CoA; then CefD2 isomerizes the compound into penicillinyl N‐CoA, which seems to be released from the enzyme by the third enzyme, a thioesterase (see Fig. 2).

The following step in the cephalosporin/cephamycin pathway is the enzymatic expansion of the five‐membered thiazolidine ring of penicillin N to a six‐membered dihydrothiazine ring. The enzyme responsible of this important conversion is the deacetoxycephalosporin C (DAOC) synthase. This protein is an intermolecular dioxygenase that requires Fe2+, molecular oxygen and α‐ketoglutarate to form DAOC and succinic acid. The DAOC synthase does not recognize (or does so very poorly) the isomer IPN, penicillin G or the deacylated 6‐aminopenicillanic acid (6‐APA) as substrates (Wu et al., 2005), although it recognizes adipyl‐ or glutaryl‐6‐APA derivatives. The DAOC synthase of Streptomyces clavuligerus has been crystallized (Öster et al., 2006) and the gene cefE has been introduced into P. chrysogenum, leading to the production of adipyl‐7‐aminodeacetoxycephalosporanic acid (ad‐7‐ADCA) and adipyl‐7‐ aminocephalosporanic acid (ad‐7‐ACA), (reviewed in Díez et al., 1997). The production of adipyl derivatives requires addition of adipic acid to the fermentation. The DAOC synthase from A. chrysogenum is also able to catalyse the next step of the pathway, namely the hydroxylation at C‐3‐forming deacetylcephalosporin C (DAC), whereas in bacteria there is a separate C‐3 hydroxylase encoded by cefF that performs this reaction.

The final step in cephalosporin C biosynthesis is the conversion of DAC to cephalosporin C by the DAC‐acetyltransferase, which uses acetyl‐CoA as donor of the acetyl group. This enzyme encoded by the cefG gene has an Mr of 49 kDa and is evolutionary similar to O‐acetylhomoserine acetyl transferases (Gutiérrez et al., 1992; Velasco et al., 1999). The cefG gene contains two introns and is linked to the cefEF gene, but in the opposite orientation (Fig. 3).

Expression of the gene cluster for penicillin biosynthesis

In P. chrysogenum, the three ‘core’ genes responsible for penicillin biosynthesis are clustered with other ORFs forming an amplifiable DNA unit of 56.8 kb (Fierro et al., 2006; van den Berg et al., 2007); this unit is present in several copies in high‐penicillin‐producing strains (Fierro et al., 1995). The genephlA encoding the phenylacetyl‐CoA ligase and the ppt gene encoding the PPTase that activates the ACV synthetase are not located in the amplifiable region.

Two of the penicillin biosynthetic genes, pcbAB and pcbC, are transcribed from divergent (bidirectional) promoter regions (Fig. 3). The expression of genes from a region containing two divergent promoters has been associated with reorganization of the chromatin structure that allows facilitated interaction of those promoter regions with the RNA polymerase II and the transcriptional factors (García et al., 2004; Ishida et al., 2006; Shwab et al., 2007).

Biosynthesis of hydrophobic penicillins in P. chrysogenum and Aspergillus nidulans is affected by several factors through complex regulatory processes (Chang et al., 1990; Aharonowitz et al., 1992; Feng et al., 1994; Martín, 2000b; Brakhage et al., 2004). Easily utilizable carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous sources dramatically affect the production of this antibiotic (Martín et al., 1999). The transcriptional regulation of the genes responsible for penicillin biosynthesis has been studied in detail. Regulatory elements have been identified (Chu et al., 1995; Feng et al., 1995; Haas and Marzluf, 1995), such as an enhancer region located in the divergent promoter pcbAB–pcbC region of P. chrysogenum, which binds a transcriptional activator named PTA1 (Kosalkováet al., 2000; 2007). However, surprisingly, no penicillin pathway‐specific regulatory genes have been found in the amplified region containing the three biosynthetic genes (Fierro et al., 2006; van den Berg et al., 2007), which indicates that penicillin biosynthesis might be controlled directly by global regulators (e.g. CreA, PacC, Nre) rather than by pathway‐specific ones.

One of these regulators is the LaeA protein, which is a nuclear methyltransferase controlling expression of the penicillin genes in P. chrysogenum (Kosalkováet al., 2009) and the synthesis of sterigmatocystin, lovastatin, penicillin and pigmentation in several aspergilli (Bok and Keller, 2004). LaeA also regulates the synthesis of gliotoxin and the virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus (Bok et al., 2005; Sugui et al., 2007). The LaeA protein contains a SAM binding site characteristic of methyltransferases and is predicted to function at the level of chromatin modification (Bok and Keller, 2004; Bok et al., 2005; 2006; Keller et al., 2005). It has been proposed that LaeA regulates the gene clusters through heterochromatin repression, perhaps by interacting with methylases or deacetylases that are associated with heterochromatin (Keller et al., 2005; Shwab et al., 2007; Kosalkováet al., 2009).

Organization and expression of the cephalosporin biosynthesis genes

While in A. nidulans and P. chrysogenum the penicillin biosynthesis genes are found in a single cluster, in A. chrysogenum the genes involved in cephalosporin biosynthesis are organized in at least two clusters located on different chromosomes. The pcbAB, pcbC, cefD1 and cefD2 genes are linked in the so‐called ‘early’ cephalosporin cluster, while the ‘late’ cluster contains the cefEF and cefG genes (Fig. 3). These genes are involved in the last two steps, which are specific for cephalosporin C biosynthesis (Gutiérrez et al., 1992).

Expression of the cephalosporin biosynthesis genes in A. chrysogenum is controlled by several global regulators including the carbon catabolite repressor CreA (Jekosch and Kück, 2000), the pH regulator PacC (Schmitt et al., 2001; 2004a) and the winged helix transcriptional factor CPCR1 (Schmitt et al., 2004b).

Recently, the velvet gene of A. chrysogenum veA has been shown to control cephalosporin biosynthesis and arthrospore formation (Dreyer et al., 2007). Acremonium chrysogenum mutants disrupted in the veA gene show an 80% reduction in the production of cephalosporin C. Analyses of the transcripts of the cephalosporin C in the mutants indicated that the main effect of the veA mutation is on expression of the cefEF gene encoding the DAOC synthase/hydroxylase enzyme, which is reduced by 85% in the mutants as compared with the parental strain (Dreyer et al., 2007).

The VeA protein carries a putative nuclear localization signal. The veA gene is found in all ascomycetes studied so far (Kim et al., 2002; Li et al., 2006). Moreover, VeA of A. chrysogenum seems to be also involved in the developmentally dependent hyphal fragmentation to form arthrospores.

In addition to the effect of this global regulator, dl‐methionine is a well‐known inducer of cephalosporin biosynthesis (Martín and Demain, 2002). Exogenous d‐ (or dl‐) methionine increases the level of mRNAs transcribed from pcbAB, pcbC and cefEF genes (Velasco et al., 1994). d‐methionine (but not l‐methionine) induces IPN synthase and deacetylcephalosporin‐C acetyltransferase and also stimulates arthrospore formation (Velasco et al., 1994). The effect of methionine may be related to that of the recently described veA‐encoded protein.

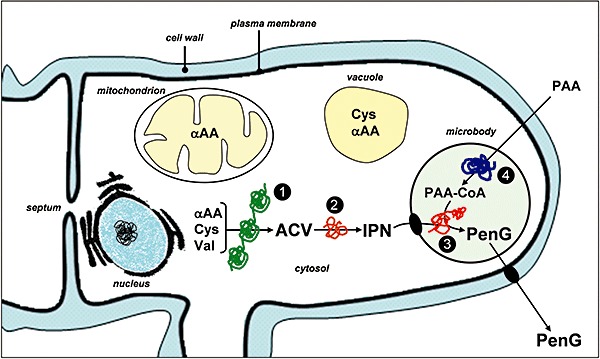

Compartmentalization of intermediates and enzymes in the biosynthesis of penicillins

The penicillin biosynthetic pathway occurs in different cellular compartments (reviewed by van de Kamp et al., 1999), which enables the spatial separation of precursors and enzymes, and the regulation and optimization of the processes involved. The distinct subcellular organization of penicillin biosynthesis implies transport of enzymes, precursors, intermediates and products through these compartments (Fig. 4). Therefore, every enzymatic step performed in an organelle has its own optimal environmental conditions.

Figure 4.

Compartmentalization of the penicillin biosynthetic pathway. Schematic representation showing the enzymatic steps and organelles involved in the penicillin biosynthetic pathway. (1) ACV synthetase; (2) IPN synthase; (3) IPN acyltransferase; (4) Phenylacetyl‐CoA (aryl‐CoA) ligase. αAA, l‐α‐aminoadipic acid; Cys, l‐cysteine; Val, l‐valine; PAA, phenylacetic acid; PAA‐CoA, phenylacetil‐CoA; PenG, benzylpenicillin.

As indicated above, the penicillin biosynthetic pathway begins with the non‐ribosomal condensation of the amino acids l‐α‐aminoadipate, l‐cysteine and l‐valine to form the tripeptide ACV. This step is catalysed by the 420 kDa ACV synthetase (Díez et al., 1990; Byford et al., 1997; Martín, 2000a). Initial studies on P. chrysogenum ACV synthetase associated this protein to membrane structures that were identified as Golgi‐like organelles (Kurylowicz et al., 1987). Additional cell fractionation experiments located ACV synthetase attached to or inside vacuoles (Müller et al., 1991; Lendenfeld et al., 1993). However, the pH for the optimal in vitro ACV synthase activity (pH = 8.4, which was higher than that of the vacuolar pH), the co‐factor requirement and protease sensitivity indicated that this enzyme is a cytosolic enzyme. Cytosolic localization of this enzyme was later confirmed by electron microscopy techniques (Van der Lende et al., 2002).

The ACV synthetase is synthesized as an inactive apoprotein form that becomes active (holo form) by means of a stand‐alone large PPTase, which covalently attaches the 4′‐phosphopantetheine moiety derived from coenzyme A (Baldwin et al., 1991a; Lambalot et al., 1996). Therefore, PPTases are necessary for penicillin biosynthesis, as it was initially reported in A. nidulans (Lambalot et al., 1996; Keszenman‐Pereyra et al., 2003; Marquez‐Fernandez et al., 2007) and recently in P. chrysogenum (García‐Estrada et al., 2008a). Stand‐alone PPTases are likely located in the cytosol because of their role in the activation of ACV synthetase and α‐aminoadipate reductase. The latter enzyme that converts α‐aminoadipate into α‐aminoadipate semialdehyde in the fungal lysine biosinthetic pathway (Casqueiro et al., 1998; Ehmann et al., 1999; Guo et al., 2001) occurs in the cytosol (Bhattacharjee, 1985; Matsuyama et al., 2006). A P. chrysogenum mutant defective in the PPTase is a lysine auxotroph due to the lack of activation of the α‐aminoadipate reductase (García‐Estrada et al., 2008a).

The amino acid precursors of the ACV tripeptide are provided through de novo synthesis, although they may also be taken up from the medium; l‐α‐aminoadipic acid, a non‐proteinogenic amino acid, is taken from the culture medium via the acidic amino acid permease and via the general amino acid permease (Trip et al., 2004). Unlike l‐cysteine and l‐valine, which are final products of primary metabolism, l‐α‐aminoadipic acid is a key intermediate in the lysine metabolism pathway of fungi (Bhattacharjee, 1985; Bañuelos et al., 1999; 2000; Nishida and Nishiyama, 2000; Zabriskie and Jackson, 2000). Mitochondria are essential organelles for the synthesis of this precursor amino acid, since enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of α‐aminoadipic acid such as homocitrate synthetase and homoisocitrate dehydrogenase are located within the mitochondrial matrix (Jaklitsch and Kubicek, 1990; Kubicek et al., 1990). Once these precursor amino acids are synthesized, they are stored in vacuoles (Lendenfeld et al., 1993). These organelles regulate the levels of l‐α‐aminoadipate and cysteine, which are toxic at moderate concentrations (Klionsky et al., 1990; Kubicek‐Pranz and Kubicek, 1991).

After the formation of ACV in the cytosol, this compound serves as substrate of the 38 kDa IPN synthase, which cyclizes the tripeptide to form IPN, an intermediate already containing the β‐lactam nucleus (Ramos et al., 1985; Carr et al., 1986; Baldwin et al., 1987; 1991b; Roach et al., 1997). The IPN synthase behaves as a soluble enzyme (Abraham et al., 1981), although its activity in cell‐free extracts seems to be stimulated by addition of Triton X‐100 or sonication (Sawada et al., 1980). This protein colocalizes with ACV synthetase in the cytosol, as it was confirmed by electron microscopy (Müller et al., 1991; Van der Lende et al., 2002).

Peroxisomal location of the IATs

Unlike the cephalosporin C biosynthetic pathway, where IPN is epimerized to form penicillin N (see below), in the penicillin pathway the l‐α‐aminoadipyl side‐chain of IPN is exchanged for a more hydrophobic side‐chain by the acyl‐CoA : IPN acyltransferase IAT (Álvarez et al., 1987; Barredo et al., 1989; Tobin et al., 1990; Whiteman et al., 1990).

The IAT is expressed as a 40 kDa precursor protein (proIAT) which undergoes an autocatalytic self‐processing between residues Gly‐102–Cys‐103 in P. chrysogenum, thus constituting a heterodimer of two subunits; α (11 kDa, corresponding to the N‐terminal fragment) and β (29 kDa, corresponding to the C‐terminal region) (Barredo et al., 1989; Veenstra et al., 1989; Tobin et al., 1990; 1993; Whiteman et al., 1990). In vivo, IAT catalyses six different reactions (Álvarez et al., 1993) related to the cleavage of IPN (releasing 6‐APA) and the replacement of the α‐aminoadipyl side‐chain of this intermediate by aromatic acids activated in the form of aryl‐CoA derivatives (Álvarez et al., 1993). As a consequence of the side‐chain substitution, hydrophobic penicillins (benzylpenicillin or phenoxyacetylpenicillin), which show a significant increase of antimicrobial activity as compared with that of IPN, are formed.

Isopenicillin N acyltransferases from P. chrysogenum and A. nidulans contain a functional peroxisomal targeting sequence PTS1 at the C‐terminal end (ARL and ANI respectively). Electron microscopy immunodetection has shown that the acyltransferase of P. chrysogenum is located inside peroxisomes (microbodies) (Müller et al., 1991; 1992; 1995; García‐Estrada et al., 2008b). In addition, transport of IAT inside the peroxisomal matrix is not dependent on the processing state of the protein, since the unprocessed proIAT variant IATC103S is correctly targeted to peroxisomes, although it is not active (García‐Estrada et al., 2008b).

Activation of the side‐chain precursor (phenylacetic acid for benzylpenicillin, or phenoxyacetic acid for phenoxymethylpenicillin) as a thioester with CoA (to form phenylacetyl‐CoA or phenoxymethyl‐CoA) is required for penicillin formation (Álvarez et al., 1993). This reaction is catalysed by aryl‐CoA ligases. These proteins belong to the acyl adenylate protein family (Turgay et al., 1992), which activate the acyl or aryl acids to acyl‐AMP or aryl‐AMP, respectively, using ATP. After activation, AMP is released and the carboxyl group is transferred to the thiol group of CoA forming a thioester. Two aryl‐CoA ligases involved in the activation of phenylacetic acid have been identified in P. chrysogenum (Lamas‐Maceiras et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007). Like IAT, phenylacetyl‐CoA ligases bear a peroxisomal targeting signal on their C‐terminus and are localized into microbodies (Gledhill et al., 1997). The localization of IAT and the two phenylacetyl‐CoA ligases in peroxisomes has been confirmed recently by physical isolation of those organelles and MS identification of the peroxisomal proteins (Kiel et al., 2009).

The peroxisomal colocalization of IAT and aryl CoA ligases indicates that the last two enzymes of the penicillin pathway form a peroxisomal functional complex, pointing to this organelle as a key compartment of the penicillin biosynthetic pathway. Peroxisomes (microbodies) are organelles that show a diameter of 200–800 nm and are surrounded by a single membrane (Müller et al., 1991). They are involved in a variety of metabolic pathways like β‐oxidation of fatty acids (Kionka and Kunau, 1985; Thieringer and Kunau, 1991a,b; Valenciano et al., 1996; 1998; Kiel et al., 2009) or karyogamy (Berteaux‐Lecellier et al., 1995). Penicillium chrysogenum microbody luminal pH has been estimated to be slightly alkaline, in the range of 7.0–7.5 (Van der Lende et al., 2002), a pH range optimal for the aryl‐CoA ligase and IAT (Álvarez et al., 1987; 1993; Gledhill et al., 1997).

The importance of microbodies in penicillin biosynthesis has been highlighted through the alteration of the number and shape of these organelles as a result of the overexpression of the Pc‐Pex11p protein (a peroxin that is involved in microbody abundance): overexpression of this protein led to an increase in the production of penicillin. This positive effect is likely to be related to an increased transport of penicillin and/or its precursors across the microbody membrane (Kiel et al., 2005), which evidences that transport events through the membrane of this organelle are very important. Because of the hydrophilic nature of IPN, the uptake of this precursor from cytosol is likely to occur through specific carriers. An active IPN transport system must be present in the peroxisomal membrane to assure an adequate pool of IPN inside microbodies. The 6‐APA is a penicillin precursor that is originally formed into the microbody by the IAT; it has been shown that this compound is taken up very efficiently through the plasma and peroxisomal membranes, probably by passive diffusion (García‐Estrada et al., 2007). The difference in the transport efficiency between IPN and 6‐APA may be due to differences in the polarity between these two compounds. The hydrophobic penicillins formed by the IAT might be released from the microbody through simple diffusion, but this hypothesis is very unlikely because the accumulated extracellular level is much higher than the intracellular one.

Are there active transport systems for large‐scale secretion of penicillin or alternative vesicle transport?

Penicillin is secreted in very large quantities by the overproducing strains. In fed‐batch cultures these industrial strains reach a biomass of about 25–30 g l−1 and they produce more than 40–50 g l−1 of penicillin. Since the last steps of penicillin biosynthesis (namely the activation of phenylacetic acid to phenylacetyl‐CoA and the transacylation reaction by the IAT) are located in peroxisomes, the final product has to be transported out of the peroxisome, first into the cytoplasm and then into the culture medium.

A significant effort has been made to clone transporters involved in the secretion of penicillin from P. chrysogenum. Penicillin secretion is sensitive to verapamil, an antagonist of multidrug transporters (van den Berg et al., 2008), suggesting that secretion is an active process involving this type of transporters. In a patent description, a large number of P. chrysogenum ABC transporters were cloned (29 different sequences) based on the conserved motifs of the transporters (van den Berg, 2001; Patent publication number WO 2001/32904). Surprisingly, genetic modification of several of these transporters did not affect the secretion of penicillin. The lack of clear involvement of any of these ABC transporters in secretion of penicillin is intriguing and may indicate that secretion of this antibiotic in the overproducing strains does not proceed through the classical ABC pumps, although this might be the case in the wild‐type strains; in other words, new secretion pathways may have been implemented in the penicillin‐overproducing strains that were absent (or inefficient) in the low‐producing wild‐type strains.

After sequencing the P. chrysogenum genome, two approaches have been used to investigate if any of those ABC transporters has a role in penicillin secretion, namely (i) transcriptional upregulation following phenylacetic acid addition to the culture and (ii) overexpression in an industrial penicillin‐producing strain when compared with the wild‐type strain (van den Berg et al., 2008).

Transcriptional studies following phenylacetic acid addition revealed two groups of MDR genes that were upregulated. However, many of those genes are probably related to phenylacetate transport and catabolism, which is known to affect penicillin biosynthesis (Rodríguez‐Sáiz et al., 2001), rather than with penicillin secretion.

The second approach, namely comparison of expression of MDR genes in a laboratory strain and in the industrial producer, revealed that some of the ABC transporters had increased expression in the industrial strain (van den Berg et al., 2008). However, a detailed functional analysis is required to confirm if the disruption or amplification of these genes affect penicillin secretion.

A gene encoding an ABC transporter of A. nidulans putatively involved in penicillin secretion was reported by Andrade and colleagues (2000). However, a detailed analysis of the reported evidence suggests that this gene is likely involved in nutrient transport, affecting directly or indirectly penicillin biosynthesis.

The pexophagy phenomenon in filamentous fungi: a putative secretion through vesicles

In a late stage of the cultures, peroxisomes are known to be integrated into vacuoles by the pexophagy phenomenon. Two types of pexophagy processes are known (Sakai et al., 2006; Kiel and van der Klei, 2009). The so‐called macro‐autophagy involves the sequestering of portions of the organelles and cytoplasm into vacuoles (Yorimitsu and Klionsky, 2005). In other cases, an autophagy process is involved in the sequestering and incorporation of peroxisomes into vacuoles. This involves several proteins encoded by the autophagy (ATG) genes (Klionsky et al., 2003). The ATG genes were initially discovered in yeasts, but recently have been reported in Podospora anserina (Pinan‐Lucarréet al., 2003; 2005), Aspergillus oryzae (Kikuma et al., 2006), A. fumigatus (Richie et al., 2007) and A. nidulans (Kiel and van der Klei, 2009).

If the peroxisomes are integrated into vacuoles, the benzylpenicillin formed in peroxisomes would be transferred to vacuoles and might be later secreted out of the cells. Although fusion of the vacuoles to the plasma membrane by an exocytosis process is possible, there is no evidence to support that this might be a major mechanism of penicillin release.

Compartmentalization and internal transport systems in the biosynthesis of cephalosporins

The cephalosporin pathway is an example of a complex secondary metabolite pathway that appears to involve several internal transporters. Only two fungal carriers have been described to be directly or indirectly involved in the β‐lactam antibiotic secretion: (i) the multidrug ABC transporter encoded by the atrD gene of A. nidulans (Andrade et al., 2000) that affects penicillin biosynthesis, and (ii) the cefT gene that is involved in transport of β‐lactam compounds in A. chrysogenum (Ullán et al., 2002b). The cefT gene is located in the early cephalosporin gene cluster and encodes a multidrug efflux pump protein belonging to the MFS class. The CefT protein is a membrane protein that has 12 transmembrane spanners (TMS) and contains all characteristic motifs of the drug: H+ antiporter 12‐TMS group of the major facilitator superfamily. Inactivation of the cefT does not reduce cephalosporin C biosynthesis, indicating that CefT is not the main transporter for cephalosporin C biosynthesis. However, when cefT was overexpresed in A. chrysogenum, it resulted in a twofold increase in total cephalosporin production (Ullán et al., 2002b).

Recently, heterologous expression of the cefT gene in the cephalosporin producer P. chrysogenum TA98, a strain carrying the cephalosporin biosynthesis genes (Ullán et al., 2007), revealed that the CefT protein is functional in P. chrysogenum acting as a hydrophilic β‐lactam transporter involved in the secretion of hydrophilic β‐lactams containing the α‐aminoadipic acid side‐chain (Ullán et al., 2008). Penicillium chrysogenum TA98 transformants showed an increase in the secretion of DAC and hydrophilic penicillins (IPN and PenN). In addition, when cefT was expressed in the parental P. chrysogenum Wis 54‐1255, it resulted in an increased secretion of IPN and a drastic reduction of benzylpenicillin production. Similar results were obtained by Nijland and colleagues (2008) with the introduction of the cefT gene of A. chrysogenum in an adipoyl‐7‐amino‐3‐carbamoyloxymethyl‐3‐cephem‐4‐carboxylic acid (ad7‐ACCCA)‐producing P. chrysogenum strain. Expression of cefT in this industrial strain results in almost a twofold increase in cephalosporin (ad‐7‐ACCCA) production.

It is noteworthy that Southern and Northern analyses showed the presence of an endogenous P. chrysogenum gene similar to cefT. The exact role of the cefT analogue is not yet known.

In A. chrysogenum all publications reported that the enzymes ACV synthetase (Baldwin et al., 1990), IPN synthase (Samsom et al., 1985), DAOC synthase‐hydroxylase (Scheidegger et al., 1984; Dotzlaf and Yeh, 1987; Samsom et al., 1987) and DAC acetyltransferase (Gutiérrez et al., 1992; Matsuda et al., 1992; Velasco et al., 1999) of the cephalosporin biosynthesis pathway have a cytosolic location (reviewed in van de Kamp et al., 1999; Evers et al., 2004).

The central step of the cephalosporin biosynthetic pathway is the conversion of isopenicillin N to penicillin N that is catalysed by the isopenicillinyl N‐CoA synthetase and isopenicillin N‐CoA epimerase proteins encoded by the cefD1 and cefD2 genes respectively (Ullán et al., 2002a). Bioinformatic analysis of the CefD1 and CefD2 proteins revealed the presence of putative peroxisomal targeting signals (PTSs) characteristic of peroxisomal matrix proteins (Reumann, 2004). Targeting and import of the peroxisomal matrix proteins depends on the PTSs present in each protein. Peroxisomal targeting signals fall into two categories: PTS1 and PTS2 (Hettema et al., 1999). The PTS1 signal is located at the C‐terminal end of proteins (consensus sequence: SKL or its derivative S/C/A‐K/R/H‐L) (Purdue and Lazarow, 2001) whereas the PTS2 signal is located at the N‐terminal region of proteins with a consensus sequence [(R/L)(L/V/I)‐X5‐(H/Q)(L/A)] (Rachubinski and Subramani, 1995; Reumann, 2004). CefD1 protein contains a putative PTS1 whereas CefD2 contains putative PST1 and PST2 targeting sequences. Moreover, the optimum pH for the in vitro conversion of IPN into PenN in A. chrysogenum cell‐free extracts was 7.0 (Baldwin et al., 1981; Jayatilake et al., 1981; Lübbe et al., 1986). This optimum pH for the PenN synthesis is the same that was estimated for the peroxisomal lumen (van der Lende et al., 2002). Recently, the CefD1 and CefD2 homologue proteins of P. chrysogenum have been found in the peroxisome matrix (Kiel et al., 2009). Therefore, the epimerization step seems to take place in peroxisomes and requires specific transport steps of precursors and intermediates across the peroxisomal membrane.

Our research group has identified some of these key metabolite transporters. Recently, we found the cefM gene (Teijeira et al., 2009) that is located in the early cephalosporin cluster (chromosome VII) downstream from cefD1 and encodes another efflux pump protein belonging to the MFS class of membrane proteins specifically to Family 3 (drug efflux proteins), the same family of the CefT protein (Ullán et al., 2002b). Bioinformatic analysis of the CefM protein sequence revealed the presence of a Pex19p‐binding domain (http://www.peroxisomedb.org/) located between amino acids 212–221. This domain is characteristic of proteins that are recruited by the Pex19 protein to be incorporated in the peroxisomal membrane (Rottensteiner et al., 2004). Targeted inactivation of cefM gene was accomplished by the two marker strategy (Liu et al., 2001; Ullán et al., 2002a,b). The disrupted mutant (Teijeira et al., 2009) showed a drastic reduction (more than 90%) in the extracellular penicillin N and cephalosporins production, and accumulated more intracellular penicillin N than the parental strain. Complementation in trans with the cefM gene cloned in integrative vectors restored the intracellular penicillin N levels, and the secreted levels of the cephalosporin intermediates and cephalosporin C.

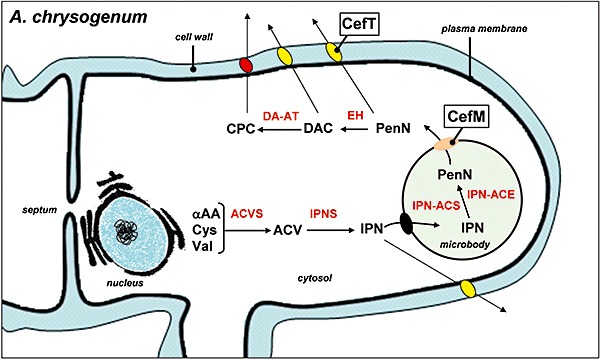

Localization of the CefM transporter

cefM–GFP fusions were used to study the in vivo localization of the CefM protein. The confocal microscopy analysis revealed a microbody localization of this protein (Teijeira et al., 2009). Taken together, these results suggest that the CefM protein is involved in the penicillin N secretion from the microbody lumen to the cytosol in A. chrysogenum and reveals a compartmentalization of the cephalosporin C biosynthetic pathway.

Based on these results, we propose a hypothetical model of compartmentalization in the biosynthesis of cephalosporins (Fig. 5). This compartmentalization model starts with the ACV and IPN synthesis in the cytosol by cytoplasmic ACV synthetase and IPN synthase (Evers et al., 2004). Later the IPN is transported to the peroxisome where it is converted in PenN by the two‐protein (CefD1–CefD2) epimerization system (Ullán et al., 2002a). Afterwards, the penicillin N is transported to the cytosol, by means of the CefM carrier (Teijeira et al., 2009), where the two last enzymes of the cephalosporin pathway synthesize cephalosporin C (van de Kamp et al., 1999; Evers et al., 2004). On the other hand, the secretion of intermediates of the cephalosporin C biosynthetic pathway in A. chrysogenum appears to be performed by the CefT trasporter (Fig. 5). Although the CefT protein has not been yet localized in A. chrysogenum using fluorescent dyes, heterologous expression of the CefT–GFP fusion in P. chrysogenum indicates that it is located in the plasma membrane (Nijland et al., 2008).

Figure 5.

Proposed model describing the compartmentalization of the cephalosporin C biosynthetic pathway in A. chrysogenum showing the localization of the CefT and CefM transporters. ACVS, δ‐l‐α‐aminoadipyl‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine synthetase; ACV, l‐δ(α‐aminoadipyl)‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine; IPNS isopenicillin N synthase; IPN, isopenicillin N; IPN‐ACS isopenicillin N‐CoA synthetase; IPN‐ACE; isopenicillin N‐CoA epimerase; PenN, penicillin N; EH, deacetoxycephalosporin synthase (expandase/hydroxylase); DAC, deacetylcephalosporin C; DAC‐AT, deacetylcephalosporin acetyltransferase; CPC, cephalosporin C.

Summary and future outlook

In summary, peroxisomes play an important role in β‐lactams synthesis as several of the key biosynthetic steps take place in this organelle. The biosynthetic pathway of cephalosporin C in A. chrysogenum is compartmentalized and takes place in the cytosol and the peroxisomes, like the biosynthetic pathway of penicillin in P. chrysogenum. The CefM protein seems to act as a transporter between the peroxisomal lumen and the cytosol to provide the penicillin N molecules for the subsequent expandase/hydroxylase and acetyl‐CoA : DAC acetyltransferase reactions. More detailed experimental work is still required to confirm the role of each of these transporters, and how to take advantage of the genetic modification of these genes to increase transport of the intermediates and secretion of the final product. Significant progress has been recently made on the proteomics of peroxisome biosynthesis (Kiel et al., 2009). The ‘omics’ studies will allow a global view of the role of organelles in fungal physiology and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Our present knowledge on transport of biosynthetic intermediates and secretion of the final products is only sketchy and further progress will depend upon scientific advance on the knowledge of secondary metabolite transporters.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants of the Eupean Union (Eurofung QLRT‐1999‐00729 and Eurofungbase), of the ADE (Agencia de Inversiones y Servicios de Castilla y León, Proyecto Genérico de Desarrollo Tecnológico 2008) and the Ministry of Industry of Spain (PROFIT: FIT‐010000‐2007‐74). C. García‐Estrada is supported by the Torres Quevedo Program (PTQ04‐3‐0411) co‐financed by the ADE Inversiones y Servicios of Castilla y León (04B/07/LE/0003).

References

- Abraham E.P., Huddlestone J.A., Jayatilake G.S., O'Sullivan J., White R.L. Conversion of δ(L‐α‐aminoadipyl)‐L‐cysteinyl‐D‐valine to isopenicillin N in cell‐free extracts of Cephalosporium acremonium. In: Gregory G.I., editor. Royal Society of Chemistry; 1981. pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Aharonowitz Y., Cohen G., Martín J.F. Penicillin and cephalosporin biosynthetic genes: structure, regulation, and evolution. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:461–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonowitz Y., Bergmeyer J., Cantoral J.M., Cohen G., Demain A.L., Fink U. Delta‐(l‐alpha‐aminoadipyl)‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine synthetase, the multienzyme integrating the four primary reactions in beta‐lactam biosynthesis, as a model peptide synthetase. Biotechnology. 1993;11:807–810. doi: 10.1038/nbt0793-807. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez E., Cantoral J.M., Barredo J.L., Díez B., Martín J.F. Purification to homogeneity and characterization of the acyl‐CoA: 6‐APA acyltransferase of Penicillium chrysogenum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1675–1682. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.11.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez E., Meesschaert B., Montenegro E., Gutiérrez S., Díez B., Barredo J.L., Martín J.F. The isopenicillin N acyltransferase of Penicillium chrysogenum has isopenicillin N amidohydrolase, 6‐aminopenicillanic acid acyltransferase and penicillin amidase activities, all of which are encoded by the single penDE gene. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade A.C., Van Nistelrooy J.G., Peery R.B., Skatrud P.L., De Waard M.A. The role of ABC transporters from Aspergillus nidulans in protection against cytotoxic agents and in antibiotic production. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;263:966–977. doi: 10.1007/pl00008697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J.E., Keeping J.W., Singh P.D., Vallejo C.A. Cell free conversion of isopenicillin N into deacetoxycephalosporin C by Cephalosporium acremonium mutant M‐0198. Biochem J. 1981;194:649–651. doi: 10.1042/bj1940649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J.E., Killin S.J., Pratt A.J., Sutherland J.D., Turner N.J., Crabbe J.C. Purification and characterization of cloned isopenicillin N synthetase. J Antibiot. 1987;40:652–659. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.652. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J.E., Bird J.W., Field R.A., O'Callaghan N.M., Schofield C.J. Isolation and partial characterisation of ACV synthetase from Cephalosporium acremonium and Streptomyces clavuligerus. J Antibiot. 1990;43:1055–1057. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J.E., Bird J.W., Field R.A., O'Callaghan N.M., Schofield C.J., Willis A.C. Isolation and partial purification of ACV synthetase from Cephalosporium acremonium and Streptomyces clavuligerus: evidence for the presence of phosphopantothenate in ACV synthetase. J Antibiot. 1991a;44:241–248. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin J.E., Lynch G.P., Schofield C.J. Isopenicillin N synthase: a new mode of reactivity. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1991b;1:736–738. [Google Scholar]

- Bañuelos O., Casqueiro J., Fierro F., Hijarrubia M.J., Gutiérrez S., Martín J.F. Characterization and lysine control of expression of the lys1 gene of Penicillium chrysogenum encoding homocitrate synthase. Gene. 1999;226:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00551-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bañuelos O., Casqueiro J., Gutiérrez S., Martín J.F. Overexpression of the lys1 gene in Penicillium chrysogenum: homocitrate synthase levels, alpha‐aminoadipic acid pool and penicillin production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;54:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s002530000359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barredo J.L., Van Solingen P., Díez B., Álvarez E., Cantoral J.M., Kattevilder A. Cloning and characterization of the acyl‐coenzyme A: 6‐aminopenicillanic‐acid‐acyltransferase gene of Penicillium chrysogenum. Gene. 1989;83:291–300. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90115-7. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg M.A. 2001.

- Van Den Berg M.A., Westerlaken I., Leeflang C., Kerkman R., Bovenberg R.A.L. Functional characterization of the penicillin biosynthetic gene cluster of Penicillium chrysogenum Wisconsin 54‐1255. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44:830–844. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berteaux‐Lecellier V., Picard M., Thompson‐Coffe C., Zickler D., Panvier‐Adoutte A., Simonet J.M. A nonmammalian homolog of the PAF1 gene (Zellweger syndrome) discovered as a gene involved in caryogamy in the fungus Podospora anserina. Cell. 1995;81:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee J.K. Alpha‐aminoadipate pathway for the biosynthesis of lysine in lower eukaryotes. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1985;12:131–151. doi: 10.3109/10408418509104427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J.W., Keller N.P. LaeA, a regulator of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus spp. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:527–535. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.527-535.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J.W., Balajee S.A., Marr K.A., Andes D., Nielsen K.F., Frisvad J.C., Keller N.P. LaeA, a regulator of morphogenetic fungal virulence factors. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1574–1582. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.9.1574-1582.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J.W., Noordermeer D., Kale S.P., Keller N.P. Secondary metabolic gene cluster silencing in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1636–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakhage A.A. Molecular regulation of beta‐lactam biosynthesis in filamentous fungi. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:547–585. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.547-585.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakhage A.A., Spröte P., Al‐Abdallah Q., Gehrke A., Plattner H., Tüncher A. Regulation of penicillin biosynthesis in filamentous fungi. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2004;88:45–90. doi: 10.1007/b99257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byford M.F., Baldwin J.E., Shiau C.Y., Schofield C.J. The mechanisms of ACV synthetase. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2631–2650. doi: 10.1021/cr960018l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr L.G., Skatrud P.L., Scheetz M.E., Queener S.W., Ingolia T.D. Cloning and expression of the isopenicillin N synthetase gene from Penicillium chrysogenum. Gene. 1986;48:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casqueiro J., Gutiérrez S., Bañuelos O., Fierro F., Velasco J., Martín J.F. Characterization of the lys2 gene of Penicillium chrysogenum encoding alpha‐aminoadipic acid reductase. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;259:549–556. doi: 10.1007/s004380050847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L.T., McGrory E.L., Elander R.P. Penicillin production by glucose‐derepressed mutants of Penicillium chrysogenum. J Ind Microbiol. 1990;6:165–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01577691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y.W., Renno D., Saunders G. Detection of a protein which binds specifically to the upstream region of the pcbAB gene in Penicillium chrysogenum. Curr Genet. 1995;28:184–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00315786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coque J.J.R., Liras P., Láiz L., Martín J.F. A gene encoding lysine 6‐aminotransferase, which forms the β‐lactam precursor α‐aminoadipic acid, is located in the cluster of cephamycin biosynthetic genes in Nocardia lactamdurans. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6258–6264. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6258-6264.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demain A.L., Martín J.F., Elander R.P. Penicillin biochemistry and genetics. In: Mateles R.I., editor. Candida; 1998. pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Díez B., Gutiérrez S., Barredo J.L., Van Solingen P., Van Der Voort L.H.M., Martín J.F. The cluster of penicillin biosynthetic genes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16358–16365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez B., Mellado E., Rodríguez M., Fouces R., Barredo J.L. Recombinant microorganisms for industrial production of antibiotics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1997;55:216–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970705)55:1<216::AID-BIT22>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotzlaf J.E., Yeh W.K. Copurification and characterization of deacetoxycephalosporin C synthetase/hydroxylase from Cephalosporium acremonium. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1611–1618. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1611-1618.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer J., Eichhorn H., Friedlin E., Kürnsteiner H., Kück U. A homologue of the Aspergillus velvet gene regulates both cephalosporin C biosynthesis and hyphal fragmentation in Acremonium chrysogenum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3412–3422. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00129-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehmann D.E., Gehring A.M., Walsh C.T. Lysine biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: mechanism of alpha‐aminoadipate reductase (Lys2) involves posttranslational phosphopantetheinylation by Lys5. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6171–6177. doi: 10.1021/bi9829940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers M.E., Trip H., Van Den Berg M.A., Bovenberg R.A.L., Driessen A.J. Compartmentalization and transport in beta‐lactam antibiotics biosynthesis. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2004;88:111–135. doi: 10.1007/b99259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Friedlin E., Marzluf G.A. A reporter gene analysis of penicillin biosynthesis gene expression in Penicillium chrysogenum and its regulation by nitrogen and glucose catabolite repression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4432–4439. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4432-4439.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Friedlin E., Marzluf G.A. Nuclear DNA‐binding proteins which recognize the intergenic control region of penicillin biosynthetic genes. Curr Genet. 1995;27:351–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00352104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierro F., Barredo J.L., Díez B., Gutiérrez S., Fernández F.J., Martín J.F. The penicillin gene cluster is amplified in tandem repeats linked by conserved hexanucleotide sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6200–6204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierro F., García‐Estrada C., Castillo N.I., Rodríguez R., Velasco‐Conde T., Martín J.F. Transcriptional and bioinformatic analysis of the 56.8 kb DNA region amplified in tandem repeats containing the penicillin gene cluster in Penicillium chrysogenum. Fungal Genet Biol. 2006;43:618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente J.L., Rumbero A., Martín J.A., Liras P. Δ‐1‐Piperideine‐6‐carboxylate dehydrogenase, a new enzyme that forms α‐aminoadipate in Streptomyces clavuligerus and other cephamycin C‐producing actinomycetes. Biochem J. 1997;327:59–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García I., Gonzalez R., Gómez D., Scazzocchio C. Chromatin rearrangements in the prnD–prnB bidirectional promoter: dependence on transcription factors. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:144–156. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.1.144-156.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Estrada C., Vaca I., Lamas‐Maceiras M., Martín J.F. In vivo transport of the intermediates of the penicillin biosynthetic pathway in tailored strains of Penicillium chrysogenum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:169–182. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0999-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Estrada C., Ullán R.V., Velasco‐Conde T., Godio R.P., Teijeira F., Vaca I. Post‐translational enzyme modification by the phosphopantetheinyl transferase is required for lysine and penicillin biosynthesis but not for roquefortine or fatty acid formation in Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochem J. 2008a;415:317–324. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080369. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Estrada C., Vaca I., Fierro F., Sjollema K., Veenhuis M., Martín J.F. The unprocessed preprotein form IATC103S of the isopenicillin N acyltransferase is transported inside peroxisomes and regulates its self‐processing. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008b;45:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gledhill L., Greaves P.A., Griffin J.P. 1997. , and) Phenylacetyl‐CoA ligase from Penicillium chrysogenum. Patent IPN WO97/02349, Smithkline Beecham UK.

- Guo S., Evans S.A., Wilkes M.B., Bhattacharjee J.K. Novel posttranslational activation of the LYS2‐encoded alpha‐aminoadipate reductase for biosynthesis of lysine and site‐directed mutational analysis of conserved amino acid residues in the activation domain of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:7120–7125. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7120-7125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez S., Díez B., Montenegro E., Martín J.F. Characterization of the Cephalosporium acremonium pcbAB gene encoding α‐aminoadiyl‐cysteinyl‐valine synthetase, a large multidomain peptide synthetase: linkage to the pcbC gene as a cluster of early cephalosporin‐biosynthetic genes and evidence of multiple functional domains. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2354–2365. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2354-2365.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez S., Velasco J., Fernández F.J., Martín J.F. The cefG gene of Cephalosporium acremonium is linked to the cefEF gene and encodes a deacetylcephalosporin C acetyltransferase closely related to homoserine O‐acetyltransferase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3056–3064. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.3056-3064.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas H., Marzluf G.A. NRE, the major nitrogen regulatory protein of Penicillium chrysogenum, binds specifically to elements in the intergenic promoter regions of nitrate assimilation and penicillin biosynthetic gene clusters. Curr Genet. 1995;28:177–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00315785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema E.H., Distel B., Tabak H.F. Import of proteins into peroxisomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1451:17–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida C., Aranda C., Valenzuela L., Riego L., Deluna A., Recillas‐Targa F. The UGA3‐GLT1 intergenic region constitutes a promoter whose bidirectional nature is determined by chromatin organization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1790–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05055.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklitsch W.M., Kubicek C.P. Homocitrate synthase from Penicillium chrysogenum. Localization, purification of the cytosolic isoenzyme, and sensitivity to lysine. Biochem J. 1990;269:247–253. doi: 10.1042/bj2690247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayatilake S., Huddleston J.A., Abraham E.P. Conversion of isopenicillin N into penicillin N in cell‐free extracts of Cephalosporium acremonium. Biochem J. 1981;194:645–647. doi: 10.1042/bj1940645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekosch K., Kück U. Loss of glucose repression in an Acremonium chrysogenum beta‐lactam producer strain and its restoration by multiple copies of the cre1 gene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;54:556–563. doi: 10.1007/s002530000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van De Kamp M., Driessen A.J., Konings W.N. Compartmentalization and transport in beta‐lactam antibiotic biosynthesis by filamentous fungi. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;75:41–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1001775932202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller N.P., Turner G., Bennett J.W. Fungal secondary metabolism – from biochemistry to genomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:937–947. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keszenman‐Pereyra D., Lawrence S., Twfieg M.E., Price J., Turner G. The npgAcfwA gene encodes a putative 4′‐phosphopantetheinyl transferase which is essential for penicillin biosynthesis in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr Genet. 2003;43:186–190. doi: 10.1007/s00294-003-0382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel J.A, Van Der Klei I.J. Proteins involved in microbody biogenesis and degradation in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46:S62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel J.A., Van Der Klei I.J., Van Den Berg M.A., Bovenberg R.A.L., Veenhuis M. Overproduction of a single protein, Pc‐Pex11p, results in 2‐fold enhanced penicillin production by Penicillium chrysogenum. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel J.A., Van Den Berg M.A., Fusetti F., Poolman B., Bovenberg R.A.L., Veenhuis M., Van Der Klei I.J. Matching the proteome to the genome: the microbody of penicillin‐producing Penicillium chrysogenum cells. Funct Integr Genomics. 2009;9:167–184. doi: 10.1007/s10142-009-0110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuma T., Ohneda M., Arioka M., Kitamoto K. Functional analysis of the ATG8 homologue Aoatg8 and role of autophagy in differentiation and germination in Aspergillus oryzae. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1328–1336. doi: 10.1128/EC.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C.F., Lee S.K., Price J., Jack R.W., Turner G., Kong R.Y. Cloning and expression analysis of the pcbAB–pcbC beta‐lactam genes in the marine fungus Kallichroma tethys. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1308–1314. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.2.1308-1314.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Han K., Kim K., Han D., Jahng K., Chae K. The veA gene activates sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet Biol. 2002;37:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s1087-1845(02)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kionka C., Kunau W.H. Inducible beta‐oxidation pathway in Neurospora crassa. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:153–157. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.153-157.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D.J., Herman P.K., Emr S.D. The fungal vacuole: composition, function, and biogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:266–292. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.266-292.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D.J., Cregg J.M., Dunn W.A., Jr, Emr S.D., Sakai Y., Sandoval I.V. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy‐related genes. Dev Cell. 2003;5:539–545. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00296-x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosalková K., Marcos A.T., Fierro F., Hernando‐Rico V., Gutiérrez S., Martín J.F. A novel heptameric sequence (TTAGTAA) is the binding site for a protein required for high level expression of pcbAB, the first gene of the penicillin biosynthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2423–2430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosalková K., Rodríguez‐Sáiz M., Barredo J.L., Martín J.F. Binding of the PTA1 transcriptional activator to the divergent promoter region of the first two genes of the penicillin pathway in different penicillium species. Curr Genet. 2007;52:229–237. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosalková K., García‐Estrada C., Ullán R.V., Godio R.P., Feltrer R., Teijeira F. The global regulator LaeA controls penicillin biosynthesis, pigmentation and sporulation, but not roquefortine C synthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. Biochimie. 2009;91:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.09.004. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek C.P., Hönlinger C.H., Jaklitsch W.M., Affenzeller K., Mach R., Gerngross T.U., Ying L. Regulation of lysine biosynthesis in the fungus Penicillium chrysogenum. In: Lubec G., Rozenthal G.A., editors. ESCOM, Science Publishers B.V; 1990. pp. 1029–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek‐Pranz E.M., Kubicek C.P. Production and biosynthesis of amino acids by fungi. In: Arora D.K., Elander R.P., Mukerji K.G., editors. Marcel Dekker; 1991. pp. 313–356. [Google Scholar]

- Kurylowicz W., Kurzatkowski W., Kurzatkowski J. Biosynthesis of benzylpenicillin by Penicillium chrysogenum and its Golgi apparatus. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 1987;35:699–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laich F., Fierro F., Cardoza R.E., Martín J.F. Organization of the gene cluster for biosynthesis of penicillin in Penicillium nalgiovense and antibiotic production in cured dry sausages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1236–1240. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1236-1240.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laich F., Fierro F., Martín J.F. Production of penicillin by fungi growing on food products: identification of a complete penicillin gene cluster in Penicillium griseofulvum and a truncated cluster in Penicillium verrucosum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1211–1219. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.3.1211-1219.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laich F., Fierro F., Martín J.F. Isolation of Penicillium nalgiovense strains impaired in penicillin production by disruption of the pcbAB gene and application as starters on cured meat products. Mycol Res. 2003;107:1–10. doi: 10.1017/s095375620300769x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas‐Maceiras M., Vaca I., Rodríguez E., Casqueiro J., Martín J.F. Amplification and disruption of the phenylacetyl‐CoA ligase gene of Penicillium chrysogenum encoding an aryl‐capping enzyme that supplies phenylacetic acid to the isopenicillin N acyltransferase. Biochem J. 2006;395:147–155. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambalot R.H., Gehring A.M., Flugel R.S., Zuber P., LaCelle M., Marahiel M.A. A new enzyme superfamily – the phosphopantetheinyl transferases. Chem Biol. 1996;3:923–936. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90181-7. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Lende T.R., Van De Kamp M., Berg M., Sjollema K., Bovenberg R.A.L., Veenhuis M. Delta‐(l‐alpha‐Aminoadipyl) Fungal Genet Biol. 2002;37:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s1087-1845(02)00036-1. et al.‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine synthetase, that mediates the first committed step in penicillin biosynthesis, is a cytosolic enzyme. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendenfeld T., Ghali D., Wolschek M., Kubicek‐Pranz E.M., Kubicek C.P. Subcellular compartmentation of penicillin biosynthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. The amino acid precursors are derived from the vacuole. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:665–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Myung K., Guse D., Donkin B., Proctor R.H., Grayburn W.S., Calvo A.M. FvVE1 regulates filamentous growth, the ratio of microconidia to macroconidia and cell wall formation in Fusarium verticillioides. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:1418–1432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liras P., Martín J.F. β‐Lactam antibiotics. In: Schaechter M., editor. 3rd. Elsevier; 2009. pp. 274–289. [Google Scholar]

- Liras P., Rodríguez‐García A., Martín J.F. Evolution of the clusters of genes for β‐lactam antibiotics: a model for evolutive combinatorial assembling of new β‐lactams. Int Microbiol. 1998;1:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Casqueiro J., Bañuelos O., Cardoza R.E., Gutiérrez S., Martín J.F. Targeted inactivation of the mecIB gene, encoding cystathionine‐gamma‐lyase, shows that the reverse transsulfuration pathway is required for high‐level cephalosporin biosynthesis in Acremonium chrysogenum C10 but not for methionine induction of the cephalosporin genes. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1765–1772. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1765-1772.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübbe C., Wolfe S., Demain A.L. Isopenicillin N epimerase activity in a high cephalosporin‐producing strain of Cephalosporium acremonium. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1986;23:367–368. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez‐Fernandez O., Trigos A., Ramos‐Balderas J.L., Viniegra‐Gonzalez G., Deising H.B., Aguirre J. Phosphopantetheinyl transferase CfwA/NpgA is required for Aspergillus nidulans secondary metabolism and asexual development. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:710–720. doi: 10.1128/EC.00362-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F. α‐Aminoadipyl‐cysteinyl‐valine synthetases in β‐lactam producing organisms. From Abraham's discoveries to novel concepts of non‐ribosomal peptide synthesis. J Antibiot. 2000a;53:1008–1021. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F. Molecular control of expression of penicillin biosynthesis genes in fungi: regulatory proteins interact with a bidirectional promoter region. J Bacteriol. 2000b;182:2355–2362. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2355-2362.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F., Demain A.L. Unraveling the methionine‐cephalosporin puzzle in Acremonium chrysogenum. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:12502–12507. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)02070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín J.F., Casqueiro J., Kosalková K., Marcos A.T., Gutiérrez S. Penicillin and cephalosporin biosynthesis: mechanism of carbon catabolite regulation of penicillin production. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;75:21–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1001820109140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín de Valmaseda E.M., Campoy S., Naranjo L., Casqueiro J., Martín J.F. Lysine is catabolized to 2‐aminoadipic acid in Penicillium chrysogenum by an omega‐aminotransferase and to saccharopine by a lysine 2‐ketoglutarate reductase. Characterization of the omega‐aminotransferase. Mol Genet Genomics. 2005;274:272–282. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A., Sugiura H., Matsuyama K., Matsumoto H., Ichikawa S., Komatsu K. Cloning and disruption of the cefG gene encoding acetyl coenzyme A: deacetylcephalosporin C o‐acetyltransferase from Acremonium chrysogenum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186:40–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama A., Arai R., Yashiroda Y., Shirai A., Kamata A., Sekido S. ORFeome cloning and global analysis of protein localization in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:841–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt1222. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller W.H., Van Der Krift T.P., Krouwer A.J., Wösten H.A., Van Der Voort L.H., Smaal E.B., Verkleij A.J. Localization of the pathway of the penicillin biosynthesis in Penicillium chrysogenum. EMBO J. 1991;10:489–495. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller W.H., Bovenberg R.A.L., Groothuis M.H., Kattevilder F., Smaal E.B., Van der Voort L.H., Verkleij A.J. Involvement of microbodies in penicillin biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1116:210–213. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(92)90118-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller W.H., Essers J., Humbel B.M., Verkleij A.J. Enrichment of Penicillium chrysogenum microbodies by isopycnic centrifugation in nycodenz as visualized with immuno‐electron microscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1245:215–220. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(95)00106-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo L., Martín de Valmaseda E., Bañuelos O., López P., Riaño J., Casqueiro J., Martín J.F. The conversion of pipecolic acid into lysine in Penicillium chrysogenum requires pipecolate oxidase and saccharopine reductase: characterization of the lys7 gene encoding saccharopine reductase. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:7165–7172. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7165-7172.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijland J.G., Kovalchuk A., Van Den Berg M.A., Bovenberg R.A.L., Driessen A.J. Expression of the transporter encoded by the cefT gene of Acremonium chrysogenum increases cephalosporin production in Penicillium chrysogenum. Fungal Genet Biol. 2008;45:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida H., Nishiyama M. What is characteristic of fungal lysine synthesis through the alpha‐aminoadipate pathway? J Mol Evol. 2000;51:299–302. doi: 10.1007/s002390010091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öster L.M., Lester D.R., Terwisscha van Scheltinga A., Svenda M., Van Lun M., Généreux C., Andersson I. Insights into cephamycin biosynthesis: the crystal structure of CmcI from Streptomyces clavuligerus. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinan‐Lucarré B., Paoletti M., Dementhon K., Coulary‐Salin B., Clavé C. Autophagy is induced during cell death by incompatibility and is essential for differentiation in the filamentous fungus Podospora anserina. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:321–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinan‐Lucarré B., Balguerie A., Clavé C. Accelerated cell death in Podospora autophagy mutants. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1765–1774. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.11.1765-1774.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdue P.E., Lazarow P.B. Peroxisome biogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:701–752. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachubinski R.A., Subramani S. How proteins penetrate peroxisomes. Cell. 1995;83:525–528. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos F.R., López‐Nieto M.J., Martín J.F. Isopenicillin N synthetase of Penicillium chrysogenum, an enzyme that converts delta‐(l‐alpha‐aminoadipyl)‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine to isopenicillin N. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:380–387. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reumann S. Specification of the peroxisome targeting signals type 1 and type 2 of plant peroxisomes by bioinformatics analyses. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:783–800. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.035584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie D.L., Fuller K.K., Fortwendel J., Miley M.D., McCarthy J.W., Feldmesser M. Unexpected link between metal ion deficiency and autophagy in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:2437–2447. doi: 10.1128/EC.00224-07. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach P.L., Clifton I.J., Fülöp V., Harlos K., Barton G.J., Hajdu J. Crystal structure of isopenicillin N synthase is the first from a new structural family of enzymes. Nature. 1995;375:700–704. doi: 10.1038/375700a0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach P.L., Clifton I.J., Hensgens C.M., Shibata N., Schofield C.J., Hajdu J., Baldwin J.E. Structure of isopenicillin N synthase complexed with substrate and the mechanism of penicillin formation. Nature. 1997;387:827–830. doi: 10.1038/42990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez‐Sáiz M., Barredo J.L., Moreno M.A., Fernández‐Cañón J.M., Peñalva M.A., Díez B. Reduced function of a phenylacetate‐oxidizing cytochrome p450 caused strong genetic improvement in early phylogeny of penicillin‐producing strains. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5465–5471. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5465-5471.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottensteiner H., Kramer A., Lorenzen S., Stein K., Landgraf C., Volkmer‐Engert R., Erdmann R. Peroxisomal membrane proteins contain common Pex19p‐binding sites that are an integral part of their targeting signals. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3406–3417. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y., Oku M., Van Der Klei I.J., Kiel J.A. Pexophagy: autophagic degradation of peroxisomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1767–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsom S.M., Belagaje R., Blankenship D.T., Chapman J.L., Perry D., Skatrud P.L. Isolation, sequence determination and expression in Escherichia coli of the isopenicillin N synthetase gene from Cephalosporium acremonium. Nature. 1985;318:191–194. doi: 10.1038/318191a0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsom S.M., Dotzlaf J.F., Slisz M.L., Becker G.W., Van Frank R.M., Veal L.E. Cloning and expression of the fungal expandase/hydroxylase gene involved in cephalosporin biosynthesis. Biotechnology. 1987;5:1207–1214. et al. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y., Baldwin J.E., Singh P.D., Solomon N.A., Demain A.L. Cell‐free cyclization of delta‐(l‐alpha‐aminoadipyl)‐l‐cysteinyl‐d‐valine to isopenicillin N. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18:465–470. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidegger A., Küenzi M.T., Nüesch J. Partial purification and catalytic properties of a bifunctional enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of beta‐lactams in Cephalosporium acremonium. J Antibiot. 1984;37:522–531. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt E.K., Kempken R., Kück U. Functional analysis of promoter sequences of cephalosporin C biosynthesis genes from Acremonium chrysogenum: specific DNA–protein interactions and characterization of the transcription factor PACC. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;265:508–518. doi: 10.1007/s004380000439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt E.K., Bunse A., Janus D., Hoff B., Friedlin E., Kürnsteiner H., Kück U. Winged helix transcription factor CPCR1 is involved in regulation of beta‐lactam biosynthesis in the fungus Acremonium chrysogenum. Eukaryot Cell. 2004a;3:121–134. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.1.121-134.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt E.K., Hoff B., Kück U. Regulation of cephalosporin biosynthesis. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2004b;88:1–43. doi: 10.1007/b99256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shwab E.K., Bok J.W., Tribus M., Galehr J., Graessle S., Keller N.P. Histone deacetylase activity regulates chemical diversity in Aspergillus. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1656–1664. doi: 10.1128/EC.00186-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugui J.A., Pardo J., Chang Y.C., Müllbacher A., Zarember K.A., Galvez E.M. Role of laeA in the regulation of alb1gliP, conidial morphology, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1552–1561. doi: 10.1128/EC.00140-07. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teijeira F., Ullán R.V., Guerra S.M., García‐Estrada C., Vaca I., Casqueiro J., Martín J.F. The transporter CefM involved in translocation of biosynthetic intermediates is essential for cephalosporin production. Biochem J. 2009;418:113–124. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieringer R., Kunau W.H. Beta‐oxidation system of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Structural characterization of the trifunctional protein. J Biol Chem. 1991a;266:13118–13123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieringer R., Kunau W.H. The beta‐oxidation system in catalase‐free microbodies of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Purification of a multifunctional protein possessing 2‐enoyl‐CoA hydratase, l‐3‐hydroxyacyl‐CoA dehydrogenase, and 3‐hydroxyacyl‐CoA epimerase activities. J Biol Chem. 1991b;266:13110–13117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin M.B., Fleming M.D., Skatrud P.L., Miller J.R. Molecular characterization of the acyl‐coenzyme A: isopenicillin N acyltransferase gene (penDE) from Penicillium chrysogenum and Aspergillus nidulans and activity of recombinant enzyme in E. coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5908–5914. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5908-5914.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin M.B., Baldwin J.E., Cole S.C.J., Miller J.R., Skatrud P.L., Sutherland J.D. The requirement for subunit interaction in the production of Penicillium chrysogenum acyl‐conenzyme A: isopenicillin N acyltransferase in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1993;132:199–206. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90196-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trip H., Evers M.E., Kiel J.A., Driessen A.J. Uptake of the beta‐lactam precursor alpha‐aminoadipic acid in Penicillium chrysogenum is mediated by the acidic and the general amino acid permease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4775–4783. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4775-4783.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgay K., Krause M., Marahiel M.A. Four homologous domains in the primary structure of GrsB are related to domains in a superfamily of adenylate forming enzymes. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:529–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullán R.V., Casqueiro J., Bañuelos O., Fernández F.J., Gutiérrez S., Martín J.F. A novel epimerization system in fungal secondary metabolism involved in the conversion of isopenicillin N into penicillin N in Acremonium chrysogenum. J Biol Chem. 2002a;277:46216–46225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullán R.V., Liu G., Casqueiro J., Gutiérrez S., Bañuelos O., Martín J.F. The cefT gene of Acremonium chrysogenum C10 encodes a multidrug efflux pump protein that significantly increases cephalosporin C production. Mol Genet Genomics. 2002b;267:673–683. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullán R.V., Campoy S., Casqueiro J., Fernández F.J., Martín J.F. Deacetylcephalosporin C production in Penicillium chrysogenum by expression of the isopenicillin N epimerization, ring expansion, and acetylation genes. Chem Biol. 2007;14:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]