Summary

When attempting to assess the extent and the implications of environmental pollution, it is often essential to quantify not only the total concentration of the studied contaminant but also its bioavailable fraction: higher bioavailability, often correlated with increased mobility, signifies enhanced risk but may also facilitate bioremediation. Genetically engineered microorganisms, tailored to respond by a quantifiable signal to the presence of the target chemical(s), may serve as powerful tools for bioavailability assessment. This review summarizes the current knowledge on such microbial bioreporters designed to assay metal bioavailability. Numerous bacterial metal‐sensor strains have been developed over the past 15 years, displaying very high detection sensitivities for a broad spectrum of environmentally significant metal targets. These constructs are based on the use of a relatively small number of gene promoters as the sensing elements, and an even smaller selection of molecular reporter systems; they comprise a potentially useful panel of tools for simple and cost‐effective determination of the bioavailability of heavy metals in the environment, and for the quantification of the non‐bioavailable fraction of the pollutant. In spite of their inherent advantages, however, these tools have not yet been put to actual use in the evaluation of metal bioavailability in a real environmental remediation scheme. For this to happen, acceptance by regulatory authorities is essential, as is a standardization of assay conditions.

Introduction

Increasing awareness of anthropogenic environmental pollution, and of its implications for human and environmental health, has led to the continuous development of two complementary approaches for assessing the degree of contamination. Physicochemical analysis, using a wide spectrum of analytical instrumentation (Bontidean et al., 2000; Köhler et al., 2000), allows highly accurate and sensitive determination of sample composition. It is essential for regulatory compliance monitoring (Belkin, 2003) as well as for understanding the sources of pollution and the means for its remediation. However, the array of analytical procedures necessary for a complete analysis of environmental samples is often costly, time‐consuming, highly complex and requires trained personnel. Furthermore, such analysis fails to provide information on the degree of bioavailability and/or the toxicity of the sample components (Köhler et al., 2000; Tauriainen et al., 2000; Flynn et al., 2003).

As a partial response to these drawbacks, a complementary bioassay‐based approach has also been implemented, and is continuously evolving in parallel to analytical methodologies. One such group of biological tools is toxicity bioassays. Rather than detect and quantify specific sample constituents, such assays quantify the global negative impact of the sample on a population of test organisms, with the end result ‘averaging’ synergistic and antagonistic effects (Belkin, 2003). The most widely used test organisms are either fish or planktonic crustaceans (Daphnia etc.), but numerous other test systems have been standardized, including the bacterial Vibrio fischeri bioluminescence test in which the decrease in light emission serves as an indication of the toxicity level (Bulich and Isenberg, 1981). A somewhat different class of bioassays aims at assessing compounds’ bioavailability; such tests attempt to distinguish between the bioavailable fraction of a compound ‘seen’ in the bioassay, and the total concentration determined by chemical analysis. Unsurprisingly, the latter often contains biologically inert, unavailable forms of the target compound (Belkin, 2003; Ivask et al., 2004; Liao et al., 2006). This phenomenon, often of concern when remediation end‐points have to be determined, carries particular significance for metal pollution (Kelly et al., 2002).

Bioavailability, bioaccessibility and their determination

Most commonly found definitions for the term ‘bioavailability’ originate from medical uses, often relating to drug absorbance in body or tissue. A somewhat broader definition (The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th Edition, 2007) refers to the degree and rate at which a substance is absorbed into a living system or becomes available at the site of physiological activity. This definition, in essence, also applies to environmental pollutants (Impellitteri et al., 2003). ‘Bioavailability processes’ have been defined by the US National Research Council (2003) to include the release of solid bound contaminants and their subsequent transport, direct contact, uptake by passage by a biological membrane and incorporation into a living system. For a contaminant to have a biological effect, however, the last two phases are not essential, as in principle chemicals may affect living systems also extracellularly. Another term occasionally used in the same context is bioaccessibility. In some cases it is used only in relation to human exposure, defined, for example, as ‘the fraction of metals that desorbs from its matrix in the gastrointestinal tract’ (Ruby et al., 1996; 1999). Only after being thus absorbed the metal in question becomes bioavailable. A broader definition is provided by Semple and colleagues (2007), who regard bioaccessibility as ‘that which is available to cross an organism's (cellular) membrane from the environment it inhabits, if the organism had access to it’. According to this definition, the bioavailable fraction of a pollutant may be only a fraction of the bioaccessible one. Bioaccessibility can be assessed with extraction by simulated saliva or gastrointestinal fluids (Ruby et al., 1996; 1999) as well as by other media (Semple et al., 2007). The latter reference provides clear schematic representations of bioavailability and bioaccessibility.

It may be generally stated that the degree by which a compound is bound to a soil or sediment particle will determine (i) the ease by which it will be washed away (such as by rainwater or irrigation) and affect, for example, water or groundwater quality, (ii) the potential facility of biological, chemical or physical remediation and (iii) the potential biological effects: although it is possible for bound contaminants to exert an effect on living systems, it is the ‘free’ forms that are the more bioavailable and pose the greater environmental risk. To properly assess such risks, it is essential that some quantitative measure of bioavailability can be used. Such information can be crucial for the design and cost‐effective implementation of (bio)remediation schemes (Kamnev and van der Lelie, 2000; Lappalainen et al., 2000; Flynn et al., 2003), including the adjustments of cleanup goals (Kelly et al., 2002; Turpeinen et al., 2003).

In response to the need to quantify the bioavailable fraction out of the total concentration of the studied chemicals, various analytical tools have been proposed. These include physical/chemical extraction techniques, some of them attempting to mimic human exposure (Ruby et al., 1996; 1999; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Oomen et al., 2004; Schroder et al., 2004; Intawongse and Dean, 2006) or plant uptake (Zhang et al., 2001; Chojnacka et al., 2005; Dayton et al., 2006), as well as an array of bioassays. The latter group includes methodologies based on molecular approaches, cell cultures, isolated tissues and organs, and whole‐animal approaches. Among the parameters tested in the latter groups are dermal and gastrointestinal adsorption, assimilation efficiency and bioaccumulation (Sijm et al., 2000; Heinz et al., 2004; Darling and Vernon, 2005; Van Straalen et al., 2005; Casteel et al., 2006,Marschner et al., 2006).

A special position among whole‐organism assays is occupied by genetically engineered microorganisms, ‘tailored’ to respond to the presence of the target compound by a readily quantifiable signal (Daunert et al., 2000; Gu et al., 2004; Melten et al., 2006; Sorensen et al., 2006; Ron, 2007; Yagi, 2007). The present review summarizes current knowledge concerning the use of such reporter microorganisms for testing the bioavailability of heavy metals in the environment.

The use of bacteria for environmental sensing offers several advantages over higher organisms, including large and homogenous populations, short generation times, facility of maintenance and storage, low costs, and rapid responses. Furthermore, bacteria can be genetically manipulated to respond in a dose‐dependant manner to specific chemicals or classes of chemicals, thus providing a true measure of bioavailability. Several extensive reviews in recent years have described the basic principles of the approach (Köhler et al., 2000; Gu et al., 2004; Verma and Singh, 2005; Harms et al., 2006; Ron, 2007; Yagi, 2007). In all cases, the promoter of a gene or an operon that is induced by the target compound(s) is fused upstream of a reporter gene system; the fusion is harboured by the host strain either as a chromosomal integration or, in most cases, in a medium‐ or high‐copy‐number plasmid. Table 1 lists the most commonly used reporter systems and the nature of the signal they generate.

Table 1.

Reporter gene systems used in metals’ biosensors design.

| Reporter gene(s) | Reporter protein | Origin | Substrate | Detection method | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lux | Bacterial luciferase | Luminescent bacteria (V. fischeri, V. harvey) | Aldehydes (C9–C14) | Luminescence | O2 required | Billard and DuBow (1998); Gu et al. (2004) |

| lucGR | Insect luciferase | Click beetle (Pyrophorus plagiophtalamus) | luciferin | Luminescence | Exogenous substrate and O2 required | Bronstein et al. (1994) |

| lucFF | Firefly (Photinus pyralis) | Tauriainen et al. (1997); Billard and DuBow (1998) | ||||

| gfp | Green fluorescent protein | Aequorea victoria | Fluorescence | Highly stable | Billard and DuBow (1998); Hakkila et al. (2002) | |

| lacZ | β‐Galactosidase | E. coli | Galactopyranosides | Colorimetric Fluorescence Electrochemical | Exogenous substrate required | Biran et al. (2000); Gu et al. (2004) |

| bla | β‐Lactamase | E. coli | Lactamides | Colorimetric | Yoon et al. (1991); Moore et al. (1997) | |

| crtA | Spheroidenone | Rhodovulum sulfidophilum | Demethylspheroidene | Colorimetric | Yagi (2007) |

Metal resistance and bacterial metal sensors

As in the genetic construction of other bacterial reporter strains, the DNA segment acting as the sensing element is a promoter of a gene induced in the presence of the target metal(s). While in some of the original reports of metal‐sensor construction the sensor elements were determined by the use of random libraries or random promoter insertions (DuBow, 1998), many of the more recent reports describe the targeted selection of promoter elements known to take part in bacterial metal resistance or uptake mechanisms. In view of the considerable involvement of bacteria in metal transformations (Fairbrother et al., 2007), there are diverse microbial biochemical reactions involving exogenous metals. Bacterial resistance may be based on extracellular precipitation, sequestration at the cell envelope, intracellular precipitation and redox transformation (Rosen et al., 1999; Brunis et al., 2000). Such mechanisms have been shown to be active both against toxic metals (Pb, Hg, Cd, As, Sb, Ag, Tl) and against dangerously high concentrations of essential metals (Zn, Fe, Ni, Cu, Co, Cr) (Bontidean et al., 2000; 2004).

Table 2 lists genetically modified bacterial metal‐sensor strains described in the scientific literature along with their sensor/reporter elements, range of concentrations detected and the induction time required prior to the accumulation of a detectable signal. It is not surprising that most target metals listed in Table 2 are heavy metals of considerable environmental significance, with Cd, Hg, As and Sb sensors comprising most of the reported constructs. All of these metals are considered ‘soft’, tending to form strong covalent bonds with ligand binding sites on external or internal biological surfaces (Fairbrother et al., 2007). ‘Hard’ metals, which often act as nutrients, preferentially form ionic bonds and are generally far less toxic. The sensitivities reported are generally high, with lowest detection thresholds in the picomolar or even femtomolar range. While some of the gene promoters used as the sensing elements are highly specific, others exhibit a broader detection range. The isiAB genes of Synechococcus, copBC of P. fluorescens and pbrR and chrA of Cupriavidus metallidurans responding only to Fe, Cu, Pb and Cr respectively are excellent examples of the former group; the arsR, cadC and merR genes of Escherichia coli represent the latter: arsR responds to As, Cd and Sb, cadC is activated by Cd, Pb, Sb, Sn and Zn, and zntA is induced by Cd, Cr, Hg, Pb and Zn. Most of the assays are relatively rapid, with the results obtained within 30–180 min. In most cases, the constructs’ responses were dose‐dependent, and bioluminescence was the dominant reporter, using either insect luc or bacterial lux. Almost all of the promoter elements used for the construction of bioreporters drive the induction of genes involved in heavy metal resistance. Only one case, that of the iron‐sensing cyanobacterial isiAB–lux fusion, is based on a sensing element involved in the acquisition of the metal as an essential nutrient. In principle, sensors of the latter type should exhibit enhanced sensitivity as they are normally geared for the detection and uptake of very low external metal concentrations.

Table 2.

Microbial metal bioavailability assays.

| Promotera (origin) | Element | Reporter geneb | Host | Linear response (µM) | Time of induction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| arsB | As3+ | blaZ | Staphylococcus aureus | 1–10 | 60 min | Ji and Silver (1992) |

| As5+ | 10–100 | |||||

| Bi | 100–1000 | |||||

| Sb | 0.2–1 | |||||

| As | luxAB (V. fischeri) | E. coli | 0.01–1 | 120 min | Cai and Dubow (1997) | |

| arsR | As | lucFF(Firefly) | E. coli | 0.01–1 | 8 h | Hakkila et al. (2002) |

| As | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | 0.01–1 | ||||

| As | lacZ | E. coli | 0.1–100 | 30 min | Ramanathan et al. (1998) | |

| Sb | 0.005–10 | |||||

| As3+ | lucFF (Firefly) | E. coli | 0.033–1 | 90 min | Tauriainen et al. (1999) | |

| As5+ | 33–33 000 | |||||

| Cd | 10–10 000 | |||||

| Sb | 0.1–100 | |||||

| As | luxAB (V. fischeri) | E. coli | 0.1–0.8 | 60 min | Stocker et al. (2003) | |

| As | luxAB (V. fischeri) | E. coli | 0.1–0.4 | Trang et al. (2005) | ||

| As | gfp (A. Victoria) | E. coli | 0.13–133 | 12 h | Roberto et al. (2002) | |

| arsR (E. coli) | As | lucGR (P. plagiophthalamus) | P. fluorescens | 0.1–10 | 120 min | Petanen et al. (2001) |

| arsR | Cd | lucFF (Firefly) | S. aureus | 0.5–5 | 120 min | Tauriainen et al. (1997) |

| Sb | 0.1–10 | |||||

| As3+ | gfp (A. Victoria) | E. coli | 0.4–25 | 120 min | Liao and Ou (2005) | |

| As5+ | 1–50 | |||||

| Sb | 0.75–8 | |||||

| arsRD | As3+ | lacZ | E. coli | 0.5–100 | 17 h | Scott et al. (1997) |

| Sb | 0.1–10 | |||||

| cadAC | Cd | blaZ | S. aureus | 0.5–100 | 90 min | Yoon et al. (1991) |

| cadC (S. aureus) | Cd | lucFF (Firefly) | Bacillus subtilis | 0.003–0.1 | 180 min | Tauriainen et al. (1998) |

| Pb | 1–10 | |||||

| Sb | 0.033–3.3 | |||||

| Sn | 33–1000 | |||||

| Zn | 1–33 | |||||

| Cd | gfp (A. Victoria) | E. coli | 0.0001–500 | 120 min | Liao et al. (2006) | |

| Pb | 0.01–10 | |||||

| Sb | 0.0001–10 | |||||

| chrB | Cr | lacZ | C. metallidurans | 0.001–50 | 8 h | Peitzsch et al. (1998) |

| chrB | Cr3+ | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | C. metallidurans | 5–80 | 90 min | Corbisier et al. (1999) |

| Cr6+ | 2.5–40 | |||||

| chrAB | Cr3+ | lucFF (Firefly) | C. metallidurans | 2–100 | 120 min | Ivask et al. (2002) |

| Cr6+ | 0.04–1 | |||||

| cnrXYH | Co | luxDABE (V. fischeri) | C. metallidurans | 9–400 | 16 h | Tibazarwa et al. (2001) |

| Ni | 0.1–60 | |||||

| copA | Ag | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | E. coli | 0.3–3 | 80 min | Riether et al. (2001) |

| Cu | 3–30 | |||||

| Ag | lucFF (Firefly) | E. coli | 0.003–0.3 | 120 min | Hakkila et al. (2004) | |

| Cu | 0.3–300 | |||||

| copBC | Cu | luxAB (V. fischeri) | P. fluorescens | 1–100 | 180 min | Tom‐Petersen et al. (2001) |

| copSRA | Cu | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | C. metallidurans | 1–200 | 90 min | Corbisier et al. (1999) |

| cup1 | Cu | gfp (A. Victoria) | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.5–5000 | 120 min | Shetty et al. (2002) |

| isiAB | Fe | luxAB (V. fischeri) | Synechococcus | 0.001–1 | 12 h | Boyanapalli et al. (2007) |

| fliC | Al | LuxAB (Vibrio harveyi) | E. coli | 40–400 | 20 min | Guzzo et al. (1992) |

| katG | Cd | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | E. coli | 2–35 | 90 min | Ben‐Israel et al. (1998) |

| merR (Shigella flexneri) | Cd | lucFF (Firefly) | E. coli | 1–100 | 60 min | Virta et al. (1995) |

| Hg | lucFF (Firefly) | 10−9–0.01 | ||||

| merR | Hg | gfp (A. Victoria) | E. coli | 0.005–0.5 | 8 h | Hakkila et al. (2002) |

| Hg | l lucFF (Firefly) | 0.005–0.1 | ||||

| Hg | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | 0.0001–0.1 | ||||

| Cd | lucFF (Firefly) | P. fluorescens | 1–10 | 120 min | Petanen et al. (2001) | |

| Hg | 10−5–0.1 | |||||

| merRB | Cd | lucFF (Firefly) | E. coli | 0.27–80 | 120 min | Ivask et al. (2002) |

| Hg | 0.1–15 | |||||

| Zn | 1380–4000 | |||||

| Hg | lucFF (Firefly) | E. coli | 0.0002–0.01 | 120 min | Ivsak et al. (2001) | |

| merRT | Hg | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | E. coli | 0.005–0.5 | 40 min | Selifonova et al. (1993) |

| Hg | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | Vibrio anguillarum | 2.5 × 10−6–5 × 10−5 | 80 min | Golding et al. (2002) | |

| merRTPA (Pseudomonas stutzeri) | Hg | luxCDABE (V fischeri) | E. coli | 0.00005–0.0005 | Pepi et al. (2006) | |

| pbrR | Pb | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | C. metallidurans | 500–5000 | 180 min | Corbisier et al. (1999) |

| pvd | Fe | gfp (A. Victoria) | Pseudomonas syringae | 0.1–100 | Overnight | Joyner and Steven (2000) |

| smtA | Zn | luxCDABE (V fischeri) | Synechococcus | 0.5–4 | 240 min | Huckle et al. (1993) |

| zntA | Cd | lacZ | E. coli | 0.0001–0.1 | 120 min | Shetty et al. (2003) |

| Cd | Red‐shifted gfp (A. Victoria) | 0.1–10 | ||||

| Pb | lacZ | 0.0001–0.1 | ||||

| Pb | Red‐shifted gfp (A. Victoria) | 0.1–10 | ||||

| Cd | luxCDABE (V. fischeri) | E. coli | 0.01–0.33 | 80 min | Riether et al. (2001) | |

| Zn | 3–30 | |||||

| Cr6+ | 30–300 | |||||

| Hg | 1–30 | |||||

| Pb | 0.03–1 | |||||

| Cd | lacZ | E. coil | 0.2–10 | 60 min | Biran et al. (2000) | |

| zntR | Cd | lucFF (Firefly) | E. coli | 0.05–30 | 120 min | Ivask et al. (2002) |

| Hg | 0.01–1 | |||||

| Zn | 40–15 000 |

Unless mentioned otherwise, the source of the promoter is the host bacterium.

Unless mentioned otherwise, the source of the reporter gene(s) is the host bacterium.

Direct availability determination in soil and sediment samples

Practically in all of the reports summarized in Table 2, the reporter strains’ responses to metal availability were characterized using standard solutions of the tested metals. As, however, the potential advantage of such tools is not in the study of laboratory solutions but rather in assessing metal availability in soils and sediments, the direct applicability of these strains to such samples is of particular interest; only a few of the quoted reports actually attempt such assays. In order to get bacterial cells in contact with soil particles, the reaction has to take place in slurry; under such circumstances, when a bacterial reporter strain responds to its target analyte, it is unclear whether its cells actually sense a bound metal atom, or whether the observed response is only to its dissolved form.

Among the few reports that address this issue, contradictory conclusions have been drawn by different researchers. Some state that soil‐ or sediment‐bound metals become bioavailable only after dissolving into the liquid phase (Ma and Uren, 1998; Rasmussen et al., 2000; Adriano, 2001). Other reports, by comparing the bacterial responses to slurries and aqueous extracts, claim that even particle‐bound metals may be available (Ivask et al., 2002; 2004; Rooney et al., 2006). The resolution of this question is of particular practical significance for risk assessment: if bound forms of the metal are indeed bioavailable, target remediation end‐points may need to be lowered and harsher cleanup measures may be required (Kelly et al., 2002). It should also be considered that while metals tend to adsorb to various solid‐phase fractions (Ivask et al., 2002), they may be released due to the activity of microorganisms and plants roots (Kahru et al., 2005).

Table 3 summarizes reported attempts to assess metal bioavailability in soils and sediments. Approximately half of the reports involve aqueous extracts, whereas in the others a direct contact assay was attempted, for either contaminated or artificially spiked samples. In almost all cases, the fraction of the total metal found to be bioavailable in the different assays was smaller than 100%. Actual values varied greatly with sample, metal and reporter strain, mostly ranging between 0.1% and 50%.

Table 3.

Bioavailability of metals in contaminated soils.

| Element | Matrix | Soil sample type (No. of samples) | Time of induction | % Bioavailable | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | WE | Polluted (3) | 120 min | 15–35 | Turpeinen et al. (2003) |

| WE | Polluted (30) | 60 min | 0.2–47 | Flynn et al. (2003) | |

| GW | Polluted (52) | 90 min | 50–110 | Trang et al. (2005) | |

| GW | Polluted (2) | 120 min | 76–92 | Liao et al. (2006) | |

| Cd | SL | Spiked (1) | 120 min | 12 | Ivask et al. (2002) |

| WE | Spiked (1) | 120 min | 0.6 | ||

| SL | Polluted (50) | 120 min | 0.5–50 | Ivask et al. (2004) | |

| WE | Polluted (50) | 120 min | 0.1–0.27 | ||

| Acetic acid extract | Polluted (40) | 120 min | 0.14–13.9 | Kahru et al. (2005) | |

| SL | Polluted (5) | 120 min | 0–55 | Liao et al. (2006) | |

| Cr6+ | SL | Spiked (1) | 120 min | 46 | Ivask et al. (2002) |

| Cu | SL | Spiked (1) | 90 min | 19–39 | Brandt et al. (2006) |

| WE | Spiked (1) | 90 min | 0.6–3.8 | ||

| Hg | SL | Spiked (1) | 120 min | 40 | Ivask et al. (2002) |

| WE | Spiked (4) | 120 min | 0.26–7.6 | Petanen and Romantschuk (2003) | |

| WE | Polluted (10) | 300 min | 20–66 | Bontidean et al. (2004) | |

| WE | Polluted (6) | 120 min | 0 | Lappalainen et al. (2000) | |

| WE | Spiked (1) | 120 min | 1.3 | Ivask et al. (2002) | |

| WE | Polluted (10)a | 120 min | 0–0.8 | Ivask et al. (2007) | |

| WE | Spiked (2) | 70–90 min | 0–1.6 | Rasmussen et al. (2000) | |

| Ni | SL | Polluted (8) | > 12 h | < DL | Everhart et al. (2006) |

| Ca(NO3)2 extract | Polluted (8) | > 12 h | 50–60 | Tibazarwa et al. (2001) | |

| Pb | SL | Polluted (50) | 120 min | 0.24–8 | Ivask et al. (2004) |

| WE | Polluted (50) | 120 min | 0.1–0.14 | ||

| Acetic acid extract | Polluted (5) | 120 min | 0.25–0.55 | Kahru et al. (2005) | |

| SL | Spiked (10) | 16 h | 0–12 | Geebelen et al. (2003) | |

| Zn | SL | Spiked (1) | 120 min | 2.6 | Tandy et al. (2005) |

| SL | Polluted (1) | 120 min | 27 | Diels et al. (1999) |

River sediment.

WE, water extract; GW, ground water; SL, soil water slurry; DL, detection limit.

Attempts to assay microbial responses to particle‐bound pollutants are also hindered by technical difficulties. Once the bacteria are mixed with a slurried soil sample, the signal emitted by the reporter strain can be distorted or optically quenched by the opaque matrix. The methodologies proposed for overcoming this problem involve the reduction of particle concentration to a minimum (Brandt et al., 2006), as well as introduction of mathematical correction factors (Lappalainen et al., 2000; Hakkila et al., 2004; Ivask et al., 2004).

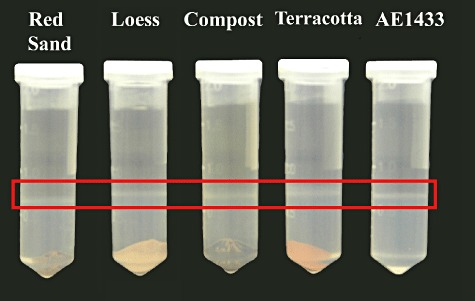

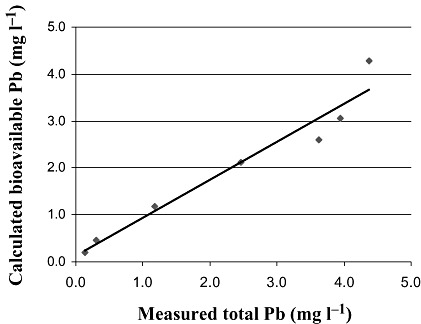

Another possible solution for this dilemma involves the separation of the reporter cells from the bulk sample after sufficient exposure has taken place. In the course of assessing Pb contamination in roadside soils, we tested the bioavailability of this element in different soil samples and subsamples using bioluminescent Cupriavidus metallidurans (previous names: Alcaligenes eutrophus, Ralstonia eutropha and Ralstonia metallidurans) CH34 reporter strain AE1433 (Corbisier et al., 1999). For this purpose we have developed a methodology for efficiently separating soil‐bacteria slurry by density centrifugation. This allowed quantifying the bacterial response with no physical interferences from suspended soil particles. Figure 1 presents several soil‐bacteria mixtures separated in this manner on a Percoll® (Sigma) gradient, with a clear bacterial band displayed above the soil pellet. This band was later removed to assess its response to the metals it was exposed to prior to the separation. We have also observed that only dissolved ions are sensed by the reporter cells. For example, when put into direct contact with a CaCO3 slurry (representing the carbonaceous fraction of the tested soil), the bioluminescent response of the tester strain was always equivalent to the amount of Pb re‐dissolved into the reaction mixture (Fig. 2). At least for this strain/sample combination, bound Pb (which amounted to 60–90% of the total metal in the sample) had no measurable biological effect. Detailed results of this study will be published elsewhere (S. Magrisso, Y. Erel, S. Belkin, in preparation).

Figure 1.

Separation of C. metallidurans AE1433 bioreporter cells (frame) from four different soils by density gradient centrifugation (80% Percoll, 12 000 r.p.m., 2 min) following a 3 h direct slurry exposure in continuous agitation. The test tube on the right contains bacterial cells that have undergone a similar treatment in the absence of a soil sample.

Figure 2.

Correlation between measured (Perkin‐Elmer 5100PC Atomic Absorption Flame Spectrometer) total Pb concentrations and calculated bioavailable Pb using C. metallidurans AE1433. CaCO3 was spiked with Pb at six different concentrations, and Pb bioavailability was determined by direct exposure of strain AE1433 to 15 mg of each of the samples. Luminescence was transformed to ‘bioavailable Pb’ using a calibration curve (bioluminescence as a function of Pb concentration in standard solutions).

Summary

Using a relatively small number of gene promoters as the sensing elements, and an even smaller selection of molecular reporter systems, numerous bacterial metal‐sensor strains have been developed over the past 15 years. As reviewed in this communication, these engineered microorganisms display very high detection sensitivities and cover a broad range of metal targets. Together, they comprise an impressive panel of tools for simple and cost‐effective determination of the bioavailability of heavy metals in the environment, and for the quantification of the non‐bioavailable fraction of the pollutant. The magnitude of this fraction should be a significant factor in the assessment of the risk posed by the polluting metal, as well as for the determination of end‐point goal in any remediation scenario. We are not aware, however, of any reported case in which such bacterial sensors, their numerous advantages notwithstanding, were actually put to use for the evaluation of metal bioavailability in a real environmental remediation scheme.

To a large extent, this lack of applied implementation of a useful set of tools is due to the fact that they have yet to be recognized by national and international regulatory agencies, and be adopted as legitimate members of the bioavailability assays arsenal. While a set of C. metallidurans‐based assays is available as a kit for general use (BIOMET®; Corbisier et al. 1998; 1999) and is routinely used in Belgian laboratories, it has not yet been recognized by any regulatory authority as an official measure of metal bioavailability. Neither are such assays specifically mentioned in the US EPA Framework for Metals Risk Assessment (Fairbrother et al., 2007). Another acute need is standardization and verification: only standardized and fully verified assays will allow meaningful risk assessment as well as the comparison of data from different sites. In addition, it would be advantageous if the detection spectrum could be expanded to cover additional metals. As indicated above, only a limited number of molecular sensing and reporting elements have been taken advantage of to date; our continuously increasing understanding of the molecular basis of both metal resistance and metal acquisition pathways should provide an almost unlimited selection of additional avenues for metal bioavailability sensor development.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Corbisier and L. Diels for their generous gift of C. metallidurans strain AE1433. Research was partially funded by the Israel Science Foundation Grant No. 226/2.

References

- Adriano D.C. Springer‐Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin S. Microbial whole‐cell sensing systems of environmental pollutants. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Israel O., Ben‐Israel H., Ulizur S. Identification and quantification of toxic chemicals by use of Escherichia coli carrying lux genes fused to stress promoters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4346–4352. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4346-4352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billard P., DuBow M.S. Bioluminescence‐based assays for detection and characterization of bacteria and chemicals in clinical laboratories. Clin Biochem. 1998;31:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(97)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biran I., Babai R., Levcov K., Rishpon J., Ron E.Z. Online and in situ monitoring of environmental pollutants: electrochemical biosensing of cadmium. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:285–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontidean I., Lloyd J.R., Hobman J.L., Wilson J.R., Csoregi E., Mattiasson B., Brown N.L. Bacterial metal‐resistance proteins and their use in biosensors for the detection of bioavailable heavy metals. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;79:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontidean I., Mortari A., Leth S., Brown N.L., Karlson U., Larsen M.M. Biosensors for detection of mercury in contaminated soils. Environ Pollut. 2004;131:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2004.02.019. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyanapalli R., Bullerjahn G.S., Pohl C., Croot P.L., Boyd P.W., McKay R., Michael L. Luminescent whole‐cell cyanobacterial bioreporter for measuring Fe availability in diverse marine environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1019–1024. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01670-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt K.K., Holm P.E., Nybroe O. Bioavailability and toxicity of soil particle‐associated copper as determined by two bioluminescent Pseudomonas fluorescens biosensors strain. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006;25:1738–1741. doi: 10.1897/05-558r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein I., Fortin J., Stanley P.E., Stewart G.S.A.B., Kricka L.J. Chemiluminescent and bioluminescent reporter gene assays. Anal Biochem. 1994;219:169–181. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunis M.R., Kapil S., Oehme W.F. Microbial resistance to metals in the environment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2000;45:198–207. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1999.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulich A.A., Isenberg D.L. Use of the luminescent bacterial system for rapid assessment of aquatic toxicity. ISA Trans. 1981;20:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Dubow S.M. Use of a luminescent bacterial biosensor for biomonitoring and characterization of arsenic toxicity of chromated copper arsenate (CCA) Biodegradation. 1997;8:105–111. doi: 10.1023/a:1008281028594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteel S.W., Weis C.P., Henningsen G.M., Brattin W.J. Estimation of relative bioavailability of lead in soil and soil‐like materials using young swine. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1162–1171. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacka K., Chojnacki A., Gorecka H., Gorecki H. Bioavailability of heavy metals from polluted soils to plants. Sci Total Environ. 2005;337:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbisier P., Mergeay M., Diels L. 1998.

- Corbisier P., Van Der Lelie D., Borremans B., Provoost A., Lorenzo V., Brown N.L. Whole cell and protein‐based biosensors for the detection of bioavailable heavy metals in environmental samples. Anal Chim Acta. 1999;387:235–244. et al. [Google Scholar]

- Darling T.R.C., Vernon T. Lead bioaccumulation in earthworms, Lumbricus terresris, from exposure to lead compounds of different solubility. Sci Total Environ. 2005;346:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daunert S., Barrett G., Feliciano J.S., Shetty R.S., Shrestha S., Smith‐Spencer W. Genetically engineered whole‐cell sensing systems: coupling biological recognition with reporter genes. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2705–2738. doi: 10.1021/cr990115p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton E.A., Basta N.T., Payton M.E., Bradham K.D., Schroder J.L., Lanno R.P. Evaluating the contribution of soil properties to modifying lead phytoavailability and phytotoxicity. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006;25:719–725. doi: 10.1897/05-307r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diels A., De Smet M., Hooybergha L., Corbisier P. Heavy metals bioremediation of soil. Mol Biotechnol. 1999;12:149–158. doi: 10.1385/MB:12:2:149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBow M.S. The detection and characterization of genetically programmed responses to environmental stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;851:286–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everhart J.L., McNear J.D., Peltier E., Van Der Lelie D., Chaney R.L., Sparks D.L. Assessing nickel bioavailability in smelter‐contaminated soils. Sci Total Environ. 2006;367:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother A., Wenstel R., Sappington K., Wood W. Framework for metal risk assessment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2007;68:145–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn C.H., Meharg A.A., Bowyer K.P., Paton G.I. Antimony bioavailability in mine soils. Environ Pollut. 2003;124:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(02)00411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geebelen W., Adriano D.C., Van Der Lelie D., Mench M., Carleer R., Clijsters H., Vangronsveld J. Selected bioavailability assays to test the efficacy of amendment‐induced immobilization of lead in soils. Plant Soil. 2003;249:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Golding G.R., Kelly C.A., Sparling R., Loewen P.C., Rudd W.M.J., Barkay T. Evidence for facilitated uptake of Hg(II) by Vibrio anguillarum and Escherichia coli under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Limnol Oceanogr. 2002;47:967–975. [Google Scholar]

- Gu M.B., Mitchell R.J., Kim C.B. Whole‐cell based biosensors for environmental biomonitoring and application. Adv Biochem Eng/Biotechnol. 2004;87:269–305. doi: 10.1007/b13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo J., Guzzo A., DuBow M.S. Characterization of the effects of aluminum on luciferase biosensors for the detection of ecotoxicity. Toxicol Lett. 1992;64–65:687–693. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(92)90248-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkila K., Maksimow M., Karp M., Virta M. Reporter genes lucFFluxCDABEgfp, and dsred have different characteristics in whole‐cell bacterial sensors. Anal Biochem. 2002;301:235–242. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkila K., Green T., Leskine P., Ivsak A., Marks R., Virta M. Detection of bioavailable heavy metals in EILATox‐Oregon samples using whole‐cell luminescent bacterial sensors in suspension or immobilized onto fiber‐optic tips. J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:333–342. doi: 10.1002/jat.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms H., Wells M.C., Van der Meer J.R. Whole‐cell living biosensors: are they ready for environmental application? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;70:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz G.H., Hoffman J.D., Audet J.D. Phosphorus amendment reduces bioavailability of lead to mallards ingesting contaminated sediments. Arch Environl Contam Toxicol. 2004;46:534–541. doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-3036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huckle J.W., Morby A.P., Turner J.S., Robinson N.J. Isolation of a prokaryotic metallothionein locus and analysis of transcriptional control by trace metal ions. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:177–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impellitteri C.A., Saxe J.K., Cochran M., Janssen G.M., Allen H.E. Predicting the bioavailability of copper and zinc in soils: modeling the partitioning of potentially bioavailable copper and zinc from soil solid to soil solution. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2003;22:1380–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intawongse M., Dean J.R. Uptake of heavy metals by vegetable plants grown on contaminated soil and their bioavailability in the human gastrointestinal tract. Food Addit Contam. 2006;23:36–48. doi: 10.1080/02652030500387554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivsak A., Hakkila K., Virta M. Detection of organomercurials with sensor bacteria. Anal Chem. 2001;73:5168–5171. doi: 10.1021/ac010550v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivask A., Virta M., Kahru A. Construction and use of specific luminescent recombinant bacterial sensors for the assessment of bioavailable fraction of cadmium, zinc, mercury and chromium in the soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34:1439–1447. [Google Scholar]

- Ivask A., Francois M., Kahru A., Dubourguier H.‐C., Virta M., Douay F. Recombinant luminescent bacterial sensors for the measurement of bioavailability of cadmium and lead in soils polluted by metal smelters. Chemosphere. 2004;55:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2003.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivask A., Green T., Polyak B., Mor A., Kahru A., Virta M., Marks R. Fiber‐optic bacterial biosensors and their application for the analysis of bioavailable Hg and As in soils and sediments from Aznalcollar mining area in Spain. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;22:1396–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G., Silver S. Regulation and expression of the arsenic resistance operon from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3684–3694. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3684-3694.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner C.D., Steven E.L. Heterogeneity of iron bioavailability on plants assessed with a whole‐cell GFP‐based bacterial biosensor. Microbiology. 2000;146:2435–2445. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahru A., Ivask A., Kasemets K., Pollumaa L., Kurvet I., Francois M., Dubourguier H.‐C. Biotests and biosensors in ecotoxicological risk assessment of field soils polluted with zinc, lead and cadmium. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2005;24:2973–2982. doi: 10.1897/05-002r1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamnev A.A., Van Der Lelie D. Chemical and biological parameters as tools to evaluate and improve heavy metal phytoremediation. Biosci Rep. 2000;20:239–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1026436806319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M.E., Brauning S.E., Schoof R.A., Ruby M.V. Battelle Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S., Belkin S., Schmid R.D. Reporter gene bioassays in environmental analysis. Fresenius J Anal Chem. 2000;366:769–779. doi: 10.1007/s002160051571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen J., Karp M., Nurmi J., Juvonen R., Virta M. Comparison of the total mercury content in sediment samples with a mercury sensor bacteria and Vibrio fischeri toxicity test. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2000;15:443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Liao V.H.‐C., Ou K.‐L. Development and testing of a green fluorescent protein‐based bacterial biosensor for measuring bioavailable arsenic in contaminated groundwater samples. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2005;24:1627–1631. doi: 10.1897/04-500r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao V.H.‐C., Chien M.‐T., Tseng Y.‐Y., Ou K.‐L. Assessment of heavy metal bioavailability in contaminated sediments and soils using green fluorescent protein‐based bacterial biosensors. Environ Pollut. 2006;142:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.B., Uren N.C. Transformation of heavy metals added to soil – application of a new sequential extraction procedure. Geoderma. 1998;84:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner B., Welge P., Hack A., Wittsiepe J., Wilhelm M. Comparison of soil Pb in vitro bioaccessibility and in vivo bioavailability with Pb pools from a sequential soil extraction. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:2812–2818. doi: 10.1021/es051617p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melten U.D., Stark B., Pagilla K. Use of genetically engineered microorganisms (GEMs) for the bioremediation of contaminants. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2006;26:145–164. doi: 10.1080/07388550600842794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J.T., Davis S.T., Dev I.K. The development of [beta]‐Lactamase as a highly versatile genetic reporter for eukaryotic cells. Anal Biochem. 1997;247:203–209. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomen A.G., Rompelberg C.J.M., Van de Kamp E., Pereboom D.P.K.H., De Zwart L.L., Sips A.J.A.M. Effect of bile type on the bioaccessibility of soil contaminants in an in vitro digestion model. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2004;46:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-2138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitzsch N., Eberz G., Nies H.D. Alcaligenes eutrophus as a bacterial chromate sensor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:453–458. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.453-458.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepi M., Reniero D., Baldi B., Barbieri P. A comparison of mer::lux whole cell biosensors and moss, a bioindicator for estimating mercury Pollut. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2006;173:163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Petanen T., Romantschuk M. Toxicity and bioavailability to bacteria of particle‐associated arsenite and mercury. Chemosphere. 2003;50:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petanen T., Virta M., Karp M., Romantschuk M. Construction and use of broad host range mercury and Arsenite sensor plasmid in the soil bacterium P. fluorescens OS8. Microbiol Ecol. 2001;41:360–368. doi: 10.1007/s002480000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan S., Shi W., Rosen B.P., Daunert S. Bacteria‐based chemiluminescence sensing system using [beta]‐galactosidase under the control of the ArsR regulatory protein of the ars operon. Anal Chim Acta. 1998;369:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen L.D., Sorensen S.J., Turner R.R., Barkay T. Application of a mer–lux biosensor for estimating bioavailable mercury in soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2000;32:639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Riether K.B., Dollard M.A., Billard P. Assessment of heavy metal bioavailability using Escherichia coli zntApxlux and copAp::lux‐based biosensors. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;57:712–716. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0852-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto F., Barnes F.M.J., Bruhn F.D. Evaluation of a GFP reporter gene construct for environmental arsenic detection. Talanta. 2002;58:181–188. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(02)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R.R., Basta T.N., Casteel S.W., Pace T. An in‐vitro gastrointestinal method to estimate bioavailable arsenic in contaminated soils and solid media. Environ Sci Technol. 1999;33:642–649. [Google Scholar]

- Ron E.Z. Biosensing environmental pollution. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney C.P., Zhao F.‐J., McGrath S.P. Soil factors controlling the expression of copper toxicity to plants in a wide range of European soils. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006;25:726–732. doi: 10.1897/04-602r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B.P., Bhattacharjee H., Zhou T., Walmsley A.R. Mechanism of the ArsA ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1461:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby M., Davis A., Schoof F., Eberle S., Sellstone C.M. Estimation of lead and arsenic bioavailabilty using a physiologically based extraction test. Environl Sci Technol. 1996;30:422–430. [Google Scholar]

- Ruby M., Schoof R., Brattin W., Goldade M., Post G., Harnois M. Advances in evaluating the oral bioavailability of inorganics in soil for use in human health risk assessment. Environ Sci Technol. 1999;33:3697–3705. et al. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder J.L., Basta T.N., Casteel S.W., Evans T.J., Payton M., Si J. Validation of the in vitro gastrointestinal (IVG) method to estimate relative bioavailable lead in contaminated soil. J Environ Qual. 2004;33:513–521. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.5130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D.L., Ramanathan S., Shi W., Rosen B.P., Daunert S. Genetically engineered bacteria: electrochemical sensing systems for antimonite and arsenite. Anal Chem. 1997;69:16–20. doi: 10.1021/ac960788x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selifonova O., Burlage R., Barkay T. Bioluminescent sensors for detection of bioavailable Hg(II) in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3083–3090. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.3083-3090.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple K.T., Doick K.J., Wick L.Y., Harms H. Microbial interactions with organic contaminants in soil: definitions, processes and measurement. Environ Pollut. 2007;150:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty S.R., Deo K.S., Liu Y., Daunert S. Fluorescence‐based sensing system for copper using genetically engineered living yeast cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;88:664–670. doi: 10.1002/bit.20331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty R.S., Deo S.K., Shah P., Sun Y., Rosen B.P., Daunert S. Luminescence‐based whole‐cell‐sensing systems for cadmium and lead using genetically engineered bacteria. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003;376:11–17. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-1862-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijm D., Kraaij R., Belfort G. Bioavailability in soil or sediment: exposure of different organisms and approaches to study it. Environ Pollut. 2000;108:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(99)00207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen S.J., Burmolle M., Hansen L.H. Making bio‐sense of toxicity: new developments in whole‐cell biosensors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker J., Balluch D., Gsell M., Harms H., Feliciano J., Daunert S. Development of a set of simple bacterial biosensors for quantitative and rapid measurements of arsenite and arsenate in potable water. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:4743–4750. doi: 10.1021/es034258b. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandy S., Barbosa V., Tye A., Preston S., Paton G., Zhang H., McGrath S. Comparison of different microbial bioassays to assess metal‐contaminated soils. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2005;24:530–536. doi: 10.1897/04-197r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauriainen S., Karp M., Chang W., Virta M. Recombinant luminescent bacteria for measuring bioavailable arsenite and antimonite. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4456–4461. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4456-4461.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauriainen S., Karp M., Chang W., Virta M. Luminescent bacterial sensor for cadmium and lead. Biosens Bioelectron. 1998;13:931–938. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(98)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauriainen S., Virta M., Chang W., Lampinen J., Karp M. Measurement of firefly luciferase reporter gene activity from cells and lysates using Escherichia coli arsenite and mercury sensors. Anal Biochem. 1999;272:191–198. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauriainen S., Virta M., Karp M. Detecting bioavailable toxic metals and metalloids from natural water samples using luminescent sensor bacteria. Water Res. 2000;34:2661–2666. [Google Scholar]

- The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, 4th Edition. 2007. ). [WWW document]. URL http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/bioavailability (retrieved from Dictionary.com website), Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, USA.

- Tibazarwa C., Corbisier P., Mench M., Bossus A., Solda P., Mergeay M. A microbial biosensor to predict bioavailable nickel in soil and its transfer to plants. Environ Pollut. 2001;113:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(00)00177-9. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom‐Petersen A., Hosbond C., Nybroe O. Identification of copper‐induced genes in Pseudomonas fluorescens and use of a reporter strain to monitor bioavailable copper in soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2001;38:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Trang P.T.K., Berg M., Viet P.H., Mui N.V., Van der Meer J.R. Bacterial bioassay for rapid and accurate analysis of arsenic in highly variable groundwater samples. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:7625–7630. doi: 10.1021/es050992e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpeinen R., Virta M., Haggblom M.M. Analysis of arsenic bioavailability in contaminated soils. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2003;22:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US National Research Council. The National Academic Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Straalen N.M., Donker M.H., Vijver M.G., Van Gastel C.A.M. Bioavailability of contaminants estimated from uptake rates into soil invertebrates. Environ Pollut. 2005;136:409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma N., Singh M. Biosensors for heavy metals. Biometals. 2005;18:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s10534-004-5787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virta M., Lampinen J., Karp M. A luminescence‐based mercury biosensor. Anal Chem. 1995;67:667–669. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi K. Application of whole‐cell bacterial sensors in biotechnology and environmental science. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;73:1251–1258. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K.P., Misra T.K., Silver S. Regulation of the cadA cadmium resistance determinant of Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7643–7649. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7643-7649.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhao F.J., Sun B., Davidson W., McGrath S.P. A new method to measure effective soil solution concentration predicts copper availability to plants. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:2602–2607. doi: 10.1021/es000268q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]