Abstract

Objective

To provide recommendations for optimized anticoagulant therapy in the inpatient setting and outline broad elements that need to be in place for effective management of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients. The guidelines are designed to promote optimization of patient clinical outcomes while minimizing the risks for potential anticoagulation-related errors and adverse events.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Because of this document’s scope, the medical literature was searched using a variety of strategies. When possible, recommendations are supported by available evidence; however, because this paper deals with processes and systems of care, high-quality evidence (eg, controlled trials) is unavailable. In these cases, recommendations represent consensus opinion of all authors and are endorsed by the Board of Directors of The Anticoagulation Forum, a organization dedicated to optimizing anticoagulation care. The Board is composed of physicians, pharmacists, and nurses with demonstrated expertise and experience in the management of patients receiving anticoagulation therapy.

Data Synthesis

Recommendations for delivering optimized inpatient anticoagulation therapy were developed collaboratively by the authors and are summarized in eight key areas: (1) process, (2) accountability, (3) integration, (4) standards of practice, (5) provider education and competency, (6) patient education (7) care transitions, (8) outcomes. Recommendations are intended to inform the development of coordinated care systems containing elements with demonstrated benefit in improvement of anticoagulation therapy outcomes. Recommendations for delivering optimized inpatient anticoagulation therapy are intended to apply to all clinicians involved in the care of hospitalized patients receiving anticoagulation therapy.

Conclusions

Anticoagulants are high-risk medications associated with a significant rate of medication errors among hospitalized patients. Several national organizations have introduced initiatives to reduce the likelihood of patient harm associated with the use of anticoagulants. Healthcare organizations are under increasing pressure to develop systems to assure the safe and effective use of anticoagulants in the inpatient setting. This document provides consensus guidelines for anticoagulant therapy in the inpatient setting and serves as a companion document to prior guidelines relevant for outpatients.

Keywords: Anticoagulant, antithrombotic, anticoagulation, thromboembolism, guideline, consensus statement, care transition, hospitalized, inpatient, medication error, patient safety

Introduction

An estimated 4 million patients in the United States and almost 7 million worldwide are taking chronic oral anticoagulants, primarily warfarin or other coumarin derivatives, for prevention and treatment of venous and arterial thromboembolism.1–2 Hospitalized patients may be treated with anticoagulants for traditional ambulatory indications such as stroke prevention for atrial fibrillation, as well as for conditions encountered primarily in the inpatient setting, including venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis and treatment, and acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Inpatients are exposed to a wide variety of anticoagulants, including unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparins (LMWH), factor-Xa inhibitors and direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs). Anticoagulants are high-risk medications associated with a significant rate of medication errors3–4 and also the leading cause of hospitalizations among older adults.5 Among hospitalized patients, anticoagulants are associated with approximately 7% of all medication errors,6–7 resulting in a 20% increased risk of death.7 Similarly, the Joint Commission’s Sentinel Event Database showed that 7.2% of all adverse medication events from Jan 1997 to December 2007 were related to anticoagulants.8

In 2008, the Joint Commission (TJC) introduced National Patient Safety Goal 03.05.01 (formerly 3E) with the intent of “reducing the likelihood of patient harm associated with the use of anticoagulant therapy”.9 Hospitals were required to “develop and implement standardized anticoagulation practices” to reduce adverse drug events (ADEs) and improve patient outcomes. Other entities, such as the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP)10 and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)11, have also introduced initiatives with similar overarching goals of reducing anticoagulant-related errors and improving patient outcomes. With healthcare regulators increasingly focused on anticoagulants, hospitals are under increasing pressure to develop systems that optimize the safety and efficacy of anticoagulants in the inpatient setting.

This document provides consensus guidelines for optimized anticoagulant therapy in the inpatient setting. It is a companion document to our prior guidelines published as “Delivery of Optimized Anticoagulant Therapy: Consensus Statement from the Anticoagulation Forum.”12 Although the prior document suggested that its recommendations should “apply to all clinicians involved in the care of patients receiving anticoagulation, regardless of the structure and setting in which that care is delivered”, there are some anticoagulation-related challenges that are unique to the inpatient arena. These guidelines will discuss broad elements that need to be in place for effective management of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients. They are designed to promote optimization of patient clinical outcomes while minimizing the risks for potential anticoagulation-related errors and adverse events. Recommendations in this document are, whenever possible, based on best available evidence. However, for some issues, published evidence is inconclusive or unavailable. In all instances, recommendations set forth represent the consensus opinion(s) of all authors and are endorsed by the Anticoagulation Forum’s Board of Directors. The Anticoagulation Forum is an organization dedicated to optimizing anticoagulation care for all patients (www.acforum.org). The Board of Directors is comprised of physicians, pharmacists and nurses with demonstrated expertise and experience in the management of hospitalized patients receiving anticoagulant therapy. The medical literature was reviewed for topics and key words including, but not limited to, standards of practice, national guidelines, patient safety initiatives and regulatory requirements pertaining to anticoagulant use in the inpatient setting. Non-english language publications were excluded. Specific MeSH terms used for our search include: algorithms, anticoagulants/administration & dosage/adverse effects/therapeutic use, clinical protocols/standards, decision support systems, drug monitoring/methods, humans, inpatients, efficiency/organizational, outcome and process assessment (Health Care), patient care team/organization & administration, program development/standards, quality improvement/organization & administration, thrombosis/drug therapy, thrombosis/prevention & control, risk assessment/standards, patient safety/standards, risk management/methods.

1. Process

Every inpatient healthcare organization should use a system-based process for inpatient anticoagulation management to assure safe and effective use of these medications

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System13, which estimated that as many as 1 out of every 25 hospitalized patients is injured due to medical error. Systems failures, rather than human error, are the cause of three-fourths of these errors.14 In response, in 2002 the ISMP introduced Pathways for Medication Safety, a comprehensive set of tools intended to help hospitals adopt a “process- driven, system-based approach” to reduce medication errors and improve patient care. This launched an era in which hundreds of safe medication practices were implemented. However, the effectiveness of these practices was reduced by a lack of standardization at both the health system level and across organizations. The need for a well-defined, formally endorsed set of safe medication practices became evident. In 2003, the National Quality Forum (NQF), in conjunction with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), introduced Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: A Consensus Report15 in an effort to standardize medication safety processes. While not all-encompassing, this NQF report details thirty-four evidence-based practices that are generalizable to a wide variety of patient populations and care settings and when properly implemented are likely to have a significant impact on patient safety and outcomes. Some of these proven practices relate directly to anticoagulation management and have been adopted by the Joint Commission and other entities. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Systematic approaches for safe and effective inpatient anticoagulation management

| System | Possible action(s) |

|---|---|

| Storage |

|

| Ordering |

|

| Preparation |

|

| Distribution |

|

| Administration |

|

| Therapeutic Management |

|

For example, use of standardized anticoagulation dosing protocols reduces errors and improves patient outcomes by providing evidence-based decision support, decreasing divergence in therapies and facilitating timely monitoring of relevant laboratory parameters.16–21 Clinicians should be encouraged to use these dosing protocols and order sets. They should be available on every floor and/or from the hospital’s electronic medical record or intranet site. Implementation of technology, such as computerized physician order entry, bar code scanning, programmable infusion pumps and dose range checking, is also associated with a decrease in medication errors.22–23 Human or computer-based alert systems result in higher rates of appropriate VTE prophylaxis and reduction in thrombotic events.24–27 While not all hospitals are able to implement technology-based systems, there are several systematic approaches to anticoagulation management that most hospitals should be able to employ. One example is a multidisciplinary approach to anticoagulation management, such as having a pharmacist on rounds, which has been shown to reduce medication errors by up to 78%.28 Pharmacy-driven inpatient anticoagulation management services have a positive impact on patient care and are another systems-based approach utilized to ensure safe and effective use of anticoagulants.29–36 Regardless of the processes or systems used, the healthcare organization should create a culture of safety that encourages reporting and discussion of anticoagulation medication errors in a non-punitive manner to promote identification of systems-based solutions.

2. Accountability

The inpatient anticoagulation management system should have a clearly defined structure with respect to leadership, accountability and responsibility, and it should promote multidisciplinary involvement

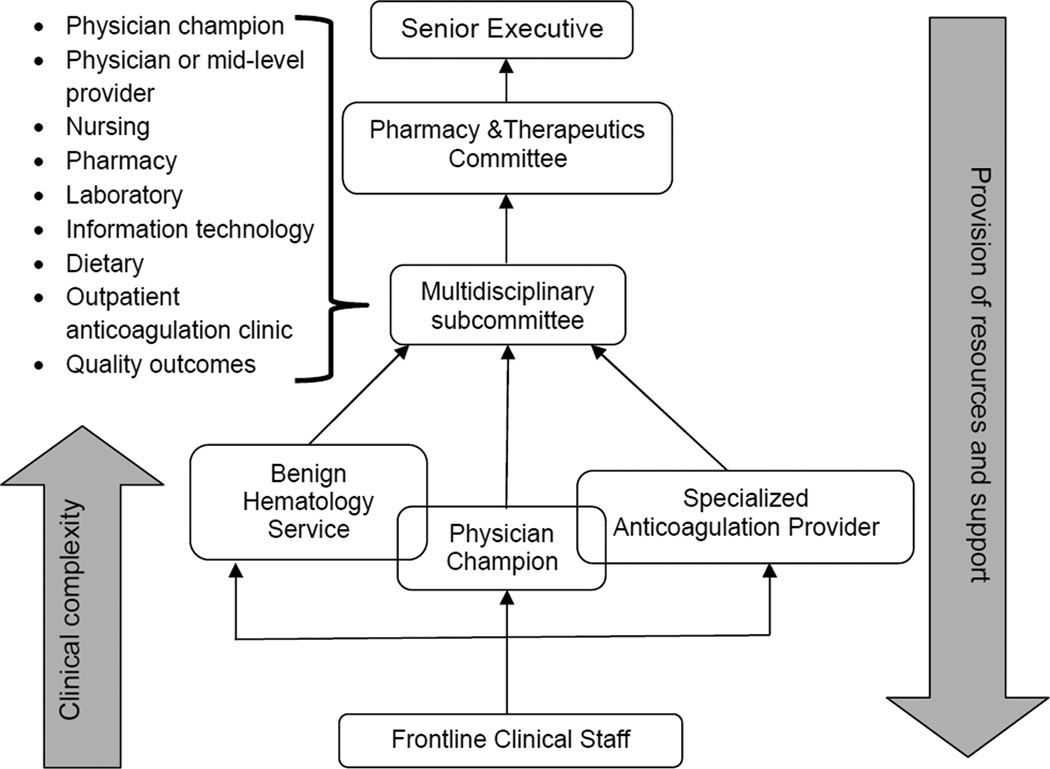

Systematic improvements within hospitals should have multidisciplinary involvement as all disciplines are likely to be affected and teamwork is integral for success. The anticoagulation multidisciplinary group or taskforce should be comprised of frontline medical staff such as physicians, nurses and pharmacists, along with supportive disciplines such as quality and safety, laboratory, dietary and information technology. Leadership within this group should be clearly delineated, with a dedicated champion (e.g. physician leader) to communicate the vision of the group and drive initiatives. Regardless of which discipline (pharmacy, nursing, physician, etc.) is the primary driver of the inpatient anticoagulation management system, accountability and responsibility for day-to-day operation of the anticoagulation management system needs to be clearly outlined in hospital policy, procedure or collaborative practice agreement for operational, clinical and medical-legal reasons. Frontline staff providing anticoagulation management need to be aware of resources to draw upon should they encounter clinical situations beyond their level of knowledge, experience or scope of practice. A hierarchy should be in place that facilitates the delegation of increasingly complex therapeutic situations upward to more knowledgeable, experienced and/or specialized practitioners. That hierarchy should also delineate a reporting structure and the relationship between the anticoagulation management system and executive level staff. Figure 1 provides one example of how such a hierarchy might be structured. However, no single model will fit all hospitals, as each will have unique characteristics, infrastructure, resources, patient demographics and regulations they must abide by.

Figure 1.

Example of Hierarchy of Inpatient Anticoagulation Management System

3. Integration

The inpatient anticoagulation management system should be reliable, sustainable, and seamlessly integrated with all patient care resources of the healthcare organization

Whenever possible, processes and tools utilized by the inpatient system of anticoagulation management should be hard-wired (electronically built and connected) into the healthcare organization and should not be person-dependent. The anticoagulation management system must incorporate a reliable means of identifying and tracking patients on anticoagulant therapy. If an outpatient anticoagulation management system is associated with the hospital and uses computer software for tracking patients, it may be beneficial to adopt the same or a similar software taylored for inpatient use. Use of evidence-based, standardized, approved anticoagulation order sets is encouraged for initiation and maintenance of anticoagulation to promote consistent, sustainable practices. Hospital administration should provide adequate resources (such as staffing, technology and support for clinical initiatives) to ensure sustainability of the anticoagulation management system. Additionally, the inpatient anticoagulation management system must be seamlessly integrated with all patient care resources in the healthcare system to facilitate accurate, efficient communication of pertinent patient information and delivery of optimized care. Table 2 provides recommendations for integration of the inpatient anticoagulation system.

Table 2.

Integration of the inpatient anticoagulation system with the healthcare organization

| • Integration of pharmacy order entry system with laboratory reporting system to promote review of key laboratory values prior to processing of orders or dispensing of anticoagulants |

| • Process for quickly communicating and responding to critical anticoagulant laboratory values or adverse events |

| • Dietary department or another responsible entity should have a method to identify patients with potential for significant drug-food interactions, authority to address these and a method to document recommendations or changes |

| • Provision of anticoagulation recommendations in a manner that is time sensitive and accessible to all practitioners |

| • Method of providing clear documentation of recommendations for dose adjustments of anticoagulants |

| • Anticoagulation education initiatives for both staff and patients aligned with initiatives, resources and workflow of the healthcare system |

| • Case management consultations to triage insurance coverage of outpatient medications and arrangement of follow up appointments |

| • Method to ensure continuity of anticoagulation management as care providers change (eg change of shift) and as patients transition to different levels of care within the hospital |

| • Method of providing clear documentation of the inpatient anticoagulation dosing history, along with any patient education or other pertinent anticoagulation information to outpatient providers in a concise, user-friendly format |

4. Standards of Practice

4.1 The inpatient anticoagulation management system should use evidence-based standards of practice to assure appropriate use of all related drug therapies in typical and special circumstances

The clinical use of anticoagulants in the inpatient setting should be organized on a drug-specific basis using protocols, guidelines, policies and procedures and/or other means to address the use of individual agents. All medical staff, house staff, pharmacists, mid-level providers and nurses should be educated on the use of these protocols, guidelines, policies and procedures. Examples of drug-specific standards of practice are noted in Table 3. It may be helpful to categorize these standards of practice as related to anticoagulant dosing, anticoagulant administration, and anticoagulant monitoring. They should be derived from evidence-based guidelines, with additional detail according to the formulary status of specific agents, as well as further evidence from clinical trials, published experience in various clinical settings, and institutional experience with individual agents.

Table 3.

Drug-Specific Standards of Practice

|

Anticoagulant use may also be organized from a disease management perspective, addressing the treatment and prevention of venous and arterial thromboembolism as well as the prevention and treatment of adverse effects associated with anticoagulant therapy. Examples of disease-specific standards of practice are noted in Table 4. These standards should be derived from evidence based guidelines, with additional institution-specific detail as necessary. A multidisciplinary approach to the development and implementation of institutional standards of practice is recommended. The input of various disciplines and specialists in the diverse aspects of anticoagulant dosing, administration and monitoring, as well as prevention, diagnosis and treatment of relevant disease states is critical to successful patient care. Leadership from hospital administration may be helpful to direct the overall process of development and implementation of clinical standards, and the guidance of a specialist “champion” is recommended.

Table 4.

Disease-Specific Standards of Practice

|

4.2 These clinical standards should be reviewed and updated on a periodic basis to assure that they reflect current evidence and are synchronized with other institutional processes, policies and procedures

A formalized method for review of institutional standards of practice is recommended. As new evidence becomes available or as new evidence-based guidelines are published, they should be incorporated into practice in a timely manner to assure the effectiveness and safety of anticoagulant therapy. In addition, as hospital processes change (for example, the transition from pharmacist order entry to CPOE), clinical standards should be aligned accordingly.

5. Provider Education and Competency

The anticoagulation management system should provide an appropriate level of staff training, ongoing educational development and documented competency assessment for all multidisciplinary personnel involved in anticoagulation management

The multidisciplinary healthcare practitioners involved in the management of anticoagulation therapy should be educated and licensed in a patient-oriented clinical discipline (i.e. medicine, nursing, pharmacy) and trained in the assessment and care of the anticoagulated patient. Inadequate knowledge about the patient’s medication or condition is one the most frequently cited causes of medication prescribing errors.37 Recognizing this risk, TJC NPSG 03.05.01 on anticoagulation therapy calls for the provision of focused anticoagulation education and training to prescribers and staff on a regular basis. Systems providing anticoagulation management should devise in-house staff educational programs and corresponding competency assessments. In addition to internal institutional-based training, formal external certification, didactic, experiential, and self-study programs can also be pursued. Examples of formal anticoagulant therapy management training programs are listed in Table 5. A multi-discipline national certification credential in anticoagulation is administered by the National Certification Board of Anticoagulation Providers (www.ncbap.org/). The credential, CACP (Certified Anticoagulation Care Provider), is inclusive of inpatient and outpatient management needs. The core domains of competency for anticoagulation providers are outlined in Table 6. Formal anticoagulant therapy management training programs should include the core domains of competency for anticoagulation providers required by the National Certification Board of Anticoagulation Providers.

Table 5.

Anticoagulation Therapy Certification and Training Programs for Multidisciplinary# Care Providers Involved in the Management of Anticoagulated Patients

Certified Anticoagulation Care Provider (CACP)

|

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Foundation Antithrombotic Pharmacotherapy Traineeship

|

University of Southern Indiana College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions Anticoagulant Therapy Management Certificate Program

|

University of Florida College of Pharmacy Anticoagulation Therapy Management Certificate Program

|

Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy

Table 6.

Competency Domains for Anticoagulation Providers

| Applied Physiology and Pathophysiology of Thromboembolic Disorders |

| working knowledge regarding the normal physiological processes of hemostasis and thrombosis, and the etiology, risk factors, and clinical manifestations of pathologic thrombus formation |

| Patient Assessment and Management |

| knowledge, skills, and competencies to manage and monitor patients on anticoagulant therapy including the ability to assess the efficacy and toxicity of the prescribed anticoagulant treatment, determine whether the therapeutic goals have been achieved, and identify patient-related variables that affect therapy |

| Patient and Family Education |

| ability to provide patient education that is tailored to patients’ specific needs to promote safety, enhance adherence, and positively affect clinical outcomes; perform an educational assessment; develop an educational plan; and document the educational activities in the patient’s medical record |

| Applied Pharmacology of Antithrombotic Agents |

| in-depth knowledge regarding the pharmacologic properties of all antithrombotic drugs |

| Operational (Administrative) Procedures |

| evaluate need for services, assess personnel and compensation requirements, develop effective communication strategies with patients and health care team, perform quality assurance and risk management activities, compliance with standards |

6. Patient Education

The anticoagulation management system should be structured to routinely provide an adequate level of patient education regarding anticoagulant therapy prior to discharge to ensure safe and effective use of these medications in the care-transition and post-discharge period

Many patients have inadequate knowledge regarding their medication therapy. To achieve better patient outcomes, patient education is a vital component of an anticoagulation therapy program. Improved outcomes have been reported when patients take responsibility for, understand, and adhere to an anticoagulation plan of care.1 TJC NPSGs mandate patient and family education be provided for those hospitalized patients receiving therapeutic anticoagulation therapy.9 The elements of patient education required by TJC include the importance of follow-up monitoring, compliance, drug-food interactions, and the potential for adverse drug reactions and interactions. (See Table 7) Effective methods of anticoagulation patient education include face-to-face interaction with a trained professional, group training sessions lasting 15–45minutes, or the use written materials and other audiovisual resources to review, teach-back and reinforce the educational process. Structured programs based on established models of education may be more likely to improve a patient’s knowledge level compared to improvised programs. Knowledge assessment tools, such as validated anticoagulation knowledge tests, can help the clinician assess and ensure that a patient’s educational needs are met.12 Teaching aids include written materials (booklets), visuals supports (video), drawings to illustrate daily situations, and medication administration calendars. Written materials provided to patients should be developed at an appropriate reading level and, when possible, in the patient’s native language. Local health literacy rates should also be factored in when developing patient educational materials.

Table 7.

Elements of Patient Education for Oral Anticoagulants

|

Novel Oral Anticoagulants Educational Points |

Anticoagulation Basics | Indicate the reason for initiating anticoagulation | Warfarin Educational Points |

| Review the name of the anticoagulant drug (generic and trade), how they work | |||

| Onset, duration, dosing, frequency, potential drug interactions, storage, reversibility, duration of therapy | |||

| Risk Benefit | Common signs and symptoms of bleeding and what to do when they occur | ||

| Common signs and symptoms of thrombosis and what to do when they occur | |||

| The need for birth control for women of child bearing age | |||

| Precautionary measures to reduce the risk of trauma or bleeding (e.g. shaving, toothbrushing, acceptable physical activities). | |||

| Common side effects or allergic type reactions | |||

| Accessing Health Care | Which health care providers (e.g. physicians, dentists) to notify of the use of anticoagulant therapy | ||

| When to notify an anticoagulation provider (dental, surgical, or invasive procedures or hospitalizations are scheduled) | |||

| Carrying identification (e.g. identification card, medical bracelet/necklace) | |||

| Adherence | Using one pharmacy for all prescription drug needs | ||

| Consequences of non-adherence or taking too much | |||

| When to take an anticoagulant medication and what to do if a dose is missed. | |||

| Lab Monitoring | Periodic (6–12 months) monitoring of renal function for novel anticoagulants | ||

| The meaning and significance of the INR for warfarin; The need for frequent INR testing and target INR values appropriate for treatment |

|||

| The narrow therapeutic index and the emphasis on regular monitoring as a way to minimize bleeding and thrombosis risk | |||

| Diet and Lifestyle | The influence of dietary vitamin K use and the need to limit or avoid alcohol |

Adapted from Garcia DA et al. Delivery of optimized anticoagulant therapy: Consensus statement from the Anticoagulation Form. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:979–988.

7. Care Transitions

The anticoagulation management system should be designed to assure appropriate care transitions for patients receiving anticoagulant therapy

The healthcare system in the United States has a fragmented structure and care transitions from one healthcare setting to another have been shown to be prone to error. Thirty-day hospital readmission rates among Medicare beneficiaries, a commonly-used indicator of appropriateness of care transitions, are nearly 20% and with associated annual costs exceeding $26 billion.38 Patients with complex or chronic medical conditions, including those on high risk anticoagulation therapy, are particularly prone to adverse outcomes from inadequate care transitions. Therefore, an inpatient anticoagulation management system should be designed to assure appropriate care transitions from inpatient to outpatient or other settings for patients receiving anticoagulation therapies, thus avoiding unnecessary readmissions.

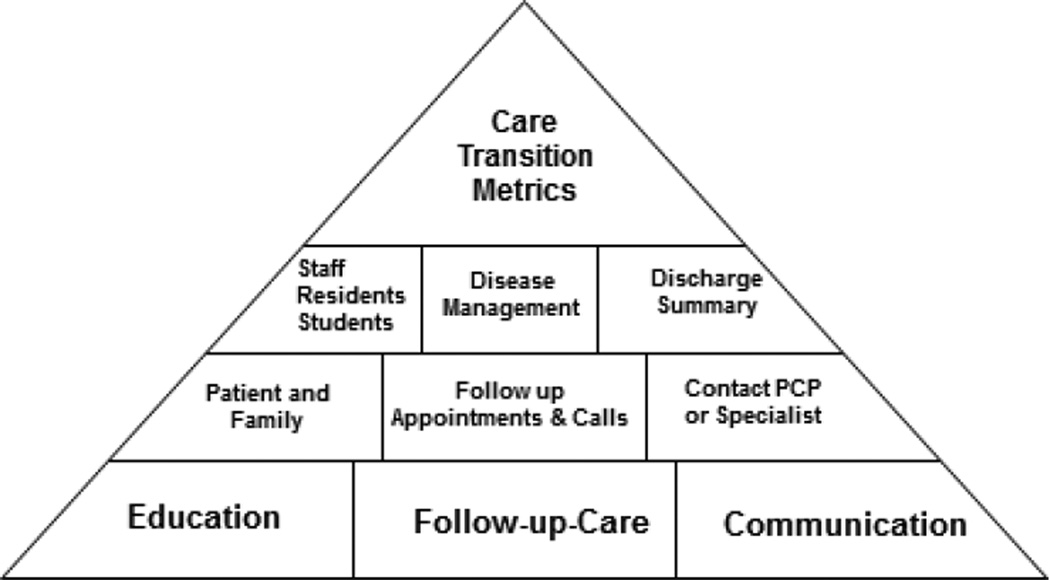

There are three fundamental elements of effective care transitions: education, follow-up care and communication. (See Figure 2) Education on anticoagulant agents through written, oral and electronic media should be provided to the patient and family as well as staff involved in the patient’s care. The empowerment of patients and their families through heightened awareness of medical conditions and appropriate use of medications is strongly recommended, as they are the most constant element in the care transition process. In addition to education on anticoagulant therapies, it is recommended that healthcare professionals undergo transition-specific competency training as most do not receive this during medical-education.

Figure 2.

Basics of Care Transition Programs

Care Transition Metrics = readmission, recurrent thromboembolic events, bleeding, follow up visits, primary care provider (PCP) or specialist contacted, discharge summary of hospitalization in 24 hours Staff (nursing, pharmacy, physicians), Residents, and Medical Students trained and involved in care transition processes

Disease Management = management of diseases requiring anticoagulation

Discharge Summary = Dictated within 24 hours of discharge

Patient and Family= Education program for patient and family

Follow up Appointments and Calls = Follow up appointments with primary care physician, specialists, anticoagulation program

Contact PCP or Specialist = Phone call placed at time of discharge to PCP and specialists

The second critical element of care-transitions is follow-up care. A follow-up appointment with the patient’s primary care physician or subspecialist should be scheduled within a pre-specified period of time after discharge to ensure patient safety. This timeframe should be delineated in hospital policy. A follow-up patient phone call within 48–72 hours after discharge is beneficial to identify issues that may occur in the immediate post-discharge period. Similarly, the patient and/or family should be provided with a “safety net” phone number prior to discharge should they need to call for assistance with barriers to care in the post-discharge period. The final step in effective care transition is communication with the receiving healthcare provider through verbal and written communication. For anticoagulant therapy, this includes inpatient dosing history, patient discharge instructions and a discharge summary. The inpatient anticoagulation management system should utilize a care transition checklist to ensure all essential elements have been addressed prior to discharge. (See Table 8) It is also essential to address care transitions when anticoagulated patients enter the hospital.

Table 8.

Care Transitions Checklist

| Element/s of care |

|---|

| Patient family education on disease state(s)and medications(s) and verbal expression of understanding |

| Demonstration of ability and comfort to self-administer parenteral anticoagulant |

| Assurance of affordability, insurance coverage and retail availability of anticoagulant therapies |

| Appropriate and accurate prescriptions given to patient prior to discharge |

| “Safety net” phone number provided to patient prior to discharge |

| Referral to outpatient anticoagulation clinic (if applicable) prior to discharge |

| Follow-up appointment within pre-specified timeframe scheduled with PCP or subspecialist prior to discharge |

| Inpatient dosing history, discharge instructions and discharge summary sent to receiving provider in time to allow for receiving provider to effectively care for the patient |

| Verbal communication between inpatient and receiving providers regarding patient’s anticoagulation therapy in time to allow for receiving provider to effectively car for the patient |

| Follow-up phone call to patient/family within 48–72 hours after discharge |

8. Outcomes

The inpatient anticoagulation system should measure pertinent quality indicators to assess the effectiveness of the system, analyze the impact on patient outcomes and identify opportunities for improvement

With healthcare costs rising rapidly, along with an increasing array of patient safety initiatives, there is increased pressure on healthcare facilities to evaluate their practices, report their findings and look for ways to improve their performance. At stake, is financial or accreditation punition for noncompliance. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) is integral to the process of improving patient safety and optimizing outcomes while reducing costs. Within CQI, there are two broad categories of quality indicators: process measures (how well the system works) and outcome measures (what impact the system ultimately has on the patient). The inpatient anticoagulation management system should be familiar with quality indicators pertinent to their organization, particularly those that are required by regulatory bodies such as CMS and TJC. Table 9 provides some examples of quality indicators relevant to inpatient anticoagulation management. The institution’s system should develop a method for tracking, reporting and responding to these indicators. It is often challenging to identify resources, such as personnel or information technology, to accomplish this and the multidisciplinary anticoagulation management team should anticipate these challenges and proactively plan for resource acquisition during the planning stages. It is recommended findings be reported to key groups within the organization, such as an anticoagulation subcommittee, pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee or hospital administration on a regular basis to showcase progress of the inpatient anticoagulation system or highlight needs for additional resources or support.

Table 9.

Anticoagulation quality indicators

| Process measures | Inpatient | Rate of use of anticoagulation protocols |

| Percentage of patients receiving anticoagulation education prior to discharge | ||

| Percentage of patients with appropriate VTE prophylaxis | ||

| Percentage of patients with appropriate duration of overlap anticoagulation therapy | ||

| Percentage of patients with appropriate lab monitoring of anticoagulation parameters | ||

| Percentage of patients with supratherapeutic INRs | ||

| Number of days to therapeutic INR | ||

| Percentage of patients with follow-up appointment scheduled prior to discharge | ||

| Transition | Percentage of patients with appropriate referral to outpatient anticoagulation clinic | |

| Percentage of patients receiving follow-up phone call within the specified time period | ||

| Rate of documented communication between inpatient and outpatient providers | ||

| Percentage of patients with discharge instructions and discharge summary sent to receiving provider | ||

| Percentage of patients with documented follow-up within pre-specified timeframe of discharge | ||

| Percentage of patients with therapeutic INR at the first follow-up visit post hospitalization | ||

| Outcome measures | Incidence of thrombotic events | |

| Incidence of bleeding events | ||

| Incidence of incidental adverse effects (eg- heparin-induced thrombocytopenia) | ||

Summary

Anticoagulants are high-risk medications associated with a significant rate of medication errors among hospitalized patients. Several national organizations have introduced initiatives to reduce the likelihood of patient harm associated with the use of anticoagulants. Healthcare organizations are under increasing pressure to develop systems to assure the safe and effective use of anticoagulants in the inpatient setting. This document provides consensus guidelines for anticoagulant therapy in the inpatient setting and serves as a companion document to prior guidelines developed for outpatients.12

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amir Jaffer, MD, Michael Gulseth, Pharm.D., and William Dager, Pharm.D. for their helpful insights and suggestions for manuscript content and development.

Funding: Dr. Nutescu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23HL112908. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This Consensus Document is endorsed by the Anticoagulation Forum’s Board of Directors: Jack E Ansell, MD, Marc Crowther, MD, MSc, David Garcia, MD, Alan Jacobson, MD, Janet Delaney, MSN, ARNP-BC, CACP, Scott Kaatz, DO, MSc, FACP, Terry Schnurr, RN, CCRC, Stephan Moll, MD, Edith A. Nutescu, PharmD, FCCP, Lynn Oertel, MS, ANP, CACP, Daniel Witt, PharmD, FCCP, BCPS, CACP, Ann Wittkowsky, PharmD, CACP, FASHP, FCCP.

Contributor Information

Edith A Nutescu, Departments of Pharmacy Practice and Administration, Center for Pharmacoeconomic Research, University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Pharmacy, Director Antithrombosis Center, Co-Director Pharmacogenomics Service, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, 833 South Wood Street, Room 164-2, Mail Code 886, Chicago, Illinois 60612, Phone: 312-996-0880, Fax: 312-413-4805, enutescu@uic.edu.

Ann K Wittkowsky, School of Pharmacy, University of Washington, Director, Anticoagulation Services, University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA.

Allison Burnett, Internal Medicine Rx Team Lead, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Geno J Merli, Jefferson Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA.

Jack E Ansell, Department of Medicine, Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, NY.

David A Garcia, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Medical Director, Anticoagulation Clinic, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

References

- 1.Garcia DA, Schwartz MJ. Warfarin therapy: Tips and tools for better control. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wysowski DK, Nourjah P, Swartz L. Bleeding complications with warfarin use: A prevalent adverse effect resulting in regulatory action. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1414–1419. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296:1858–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.QuarterWatch. Monitoring FDA MedWatch Reports. [Accessed January 7,2013];Anticoagulants the Leading Reported Drug Risk in 2011. Available from: http://www.ismp.org/QuarterWatch/pdfs/2011Q4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency Hospitalizations for Adverse Drug Events in Older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fanikos J, Stapinski C, Koo S, Kucher N, Tsilimingras K, Goldhaber SZ. Medication errors associated with anticoagulant therapy in the hospital. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:532–535. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond CA, Raehl CL. Adverse drug reactions in united states hospitals. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:601–608. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Joint Commission, Sentinel event alert. Preventing errors relating to commonly used anticoagulants. [Accessed January 7,2013]; Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_41.PDF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Joint Commission, National patient safety goals NPSG 03.01.05. [Accessed January 7, 2013]; Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/NPSG_Chapter_Jan2013_AHC.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute for Safe Medication Practices. [Accessed January 7,2013];Improving medication safety with anticoagulant therapy. Available from: http://www.ismp.org/tools/anticoagulantTherapy.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital-acquired conditions. [Accessed January 7,2013]; Available from: http://www.cms.gov/HospitalAcqCond/06_Hospital-Acquired_Conditions.asp.

- 12.Garcia DA, Witt DM, Hylek E, Wittkowsky AK, Nutescu EA, Jacobson A, et al. Delivery of optimized anticoagulant therapy: Consensus statement from the anticoagulation forum. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:979–988. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. [Accessed January 7,2013];1999 Available from: http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Cooper J, Demonaco HJ, Gallivan T, et al. Systems analysis of adverse drug events. ADE prevention study group. JAMA. 1995;274:35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Quality Forum. Safe practices for better healthcare. [Accessed January 7,2013]; Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2009/03/Safe_Practices_for_Better_Healthcare%e2%80%932009_Update.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raschke RA, Reilly BM, Guidry JR, Fontana JR, Srinivas S. The weight-based heparin dosing nomogram compared with a "standard care" nomogram. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:874–881. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-9-199311010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott CG, Hiltunen SJ, Suchyta M, Hull RD, Raskob GE, Pineo GF, et al. Physician-guided treatment compared with a heparin protocol for deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:999–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruickshank MK, Levine MN, Hirsh J, Roberts R, Siguenza M. A standard heparin nomogram for the management of heparin therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollingsworth JA, Rowe BH, Brisebois FJ, Thompson PR, Fabris LM. The successful application of a heparin nomogram in a community hospital. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:2095–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips WS, Smith J, Greaves M, Preston FE, Channer KS. An evaluation and improvement program for inpatient anticoagulant control. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown G, Dodek P. An evaluation of empiric vs nomogram-based dosing of heparin in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1534–1538. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199709000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates DW, Teich JM, Lee J, Seger D, Kuperman GJ, Ma'Luf N, et al. The impact of computerized physician order entry on medication error prevention. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6:313–321. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1999.00660313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poon EG, Keohane CA, Yoon CS, Ditmore M, Bane A, Levtzion-Korach O, et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1698–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia DA, Highfill J, Finnerty K, Varoz E, McConkey S, Hutchinson K, et al. A prospective, controlled trial of a pharmacy-driven alert system to increase thromboprophylaxis rates in medical inpatients. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2009;20:541–545. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32832d6cfc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, Cooper JM, Paterno MD, Soukonnikov B, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:969–977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piazza G, Rosenbaum EJ, Pendergast W, Jacobson JO, Pendleton RC, McLaren GD, et al. Physician alerts to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Circulation. 2009;119:2196–2201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.841197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobieraj DM. Development and implementation of a program to assess medical patients' need for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1755–1760. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kucukarslan SN, Peters M, Mlynarek M, Nafziger DA. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2014–2018. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dager WE, Gulseth MP. Implementing anticoagulation management by pharmacists in the inpatient setting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1071–1079. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dager WE, Branch JM, King JH, White RH, Quan RS, Musallam NA, et al. Optimization of inpatient warfarin therapy: Impact of daily consultation by a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation service. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:567–572. doi: 10.1345/aph.18192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bond CA, Raehl CL. Pharmacist-provided anticoagulation management in United States hospitals: Death rates, length of stay, medicare charges, bleeding complications, and transfusions. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:953–963. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.11.953.36133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donovan JL, Drake JA, Whittaker P, Tran MT. Pharmacy-managed anticoagulation: Assessment of in-hospital efficacy and evaluation of financial impact and community acceptance. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;22:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-8328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locke C, Ravnan SL, Patel R, Uchizono JA. Reduction in warfarin adverse events requiring patient hospitalization after implementation of a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation service. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:685–689. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.5.685.63582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schillig J, Kaatz S, Hudson M, Krol GD, Szandzik EG, Kalus JS. Clinical and safety impact of an inpatient pharmacist-directed anticoagulation service. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:322–328. doi: 10.1002/jhm.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellis RF, Stephens MA, Sharp GB. Evaluation of a pharmacy-managed warfarin-monitoring service to coordinate inpatient and outpatient therapy. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:387–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rivey MP, Peterson JP. Pharmacy-managed, weight-based heparin protocol. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50:279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tully MP, Ashcroft DM, Dornan T, Lewis PJ, Taylor D, Wass V. The causes of and factors associated with prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32:819–836. doi: 10.2165/11316560-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]