During the past year, a newly identified human coronavirus (hCoV) associated with severe respiratory disease and occasionally acute renal failure has emerged in the Middle East.1 A total of 15 laboratory-confirmed human cases have been reported from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Jordan, and England, with 9 deaths. The first human isolate of hCoV-EMC/20121 was classified as a betacoronavirus, which placed it in the same genus as the coronavirus that causes the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).2 Studies revealed a broad tropism for replication in cell lines originating from different mammalian species, potentially indicating a low barrier for cross-species transmission.3 This situation reminds the infectious-disease community of the emergence of the SARS coronavirus and calls for immediate public health preparedness and response with rapid, reliable diagnostic tests and vigilant surveillance. The availability of an animal disease model is an important aspect of developing effective countermeasures.

Here we report a nonhuman primate disease model for hCoV-EMC/2012, with the virus provided by the Erasmus Medical Center. Six rhesus macaques between the ages of 6 and 12 years were inoculated with 7 million 50% tissue-culture infectious doses (TCID50) of hCoV-EMC/2012 through a combination of intratracheal, intranasal, oral, and ocular routes, following an established protocol.4 Clinical signs of disease developed in all six animals within 24 hours. These signs included reduced appetite, elevated temperature, increased respiration rate, cough, piloerection, and hunched posture. Clinical signs were transient and lasted for a few days. Radiographic changes showed varying degrees of localized infiltration and interstitial markings (Fig. 1A).

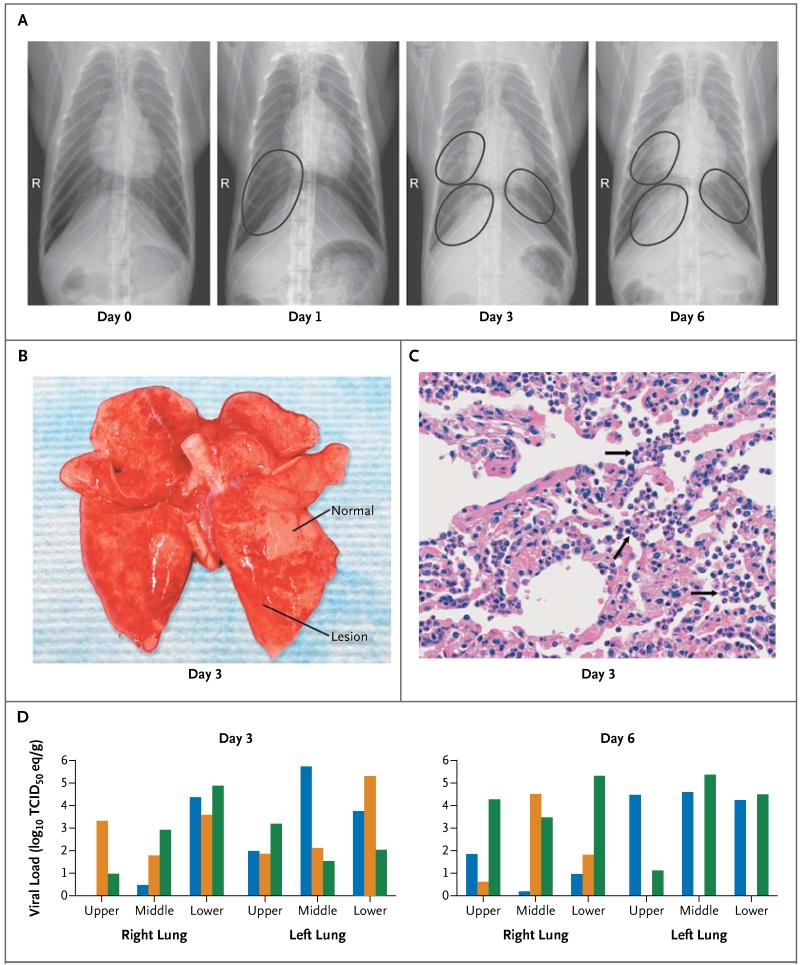

Figure 1. Radiographic and Histopathological Findings and Viral Loads in Lungs of Rhesus Macaques Inoculated with hCoV-EMC/2012.

Panel A shows ventrodorsal thoracic radiographs taken before inoculation and 1, 3, and 6 days after inoculation with hCoV-EMC/2012. The circled areas are regions of interstitial infiltrates indicative of viral pneumonia. Panel B shows a view of the ventral lung of an infected animal obtained on autopsy on day 3 after inoculation, showing both normal and affected tissue. Panel C shows histopathological analysis of lung tissue collected on day 3 after inoculation, with infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages associated with acute interstitial pneumonia (arrows; hematoxylin and eosin). Panel D shows viral loads in right and left upper, middle, and lower lung lobes on day 3 (left) and 6 (right) after inoculation. After the collection of lung samples, tissues were homogenized, RNA was extracted, and quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction analysis was performed. Log10 equivalents of 50% tissue-culture infective doses (TCID50 eq) were calculated per gram of tissue. Each bar represents one animal.

After the animals were euthanized, postmortem examinations showed multifocal to coalescent bright red lesions throughout the lower respiratory tract indicative of acute pneumonia (Fig. 1B). These lesions progressed into dark reddish purple areas of pulmonary inflammation, as seen on histopathological analysis (Fig. 1C), with fibrous adhesions, consolidation, and edematous and atelectatic areas in the lungs. No extrapulmonary lesions were observed. Hematologic and blood chemical analyses showed a transient early increase in white cells, but otherwise values were within normal ranges, supporting an organ-specific process rather than a systemic infection. Quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction analysis5 of lung tissue revealed the widespread presence of hCoV-EMC/2012 the lower respiratory tract (Fig. 1D), with viral loads decreasing over time. Virus was reisolated from lung tissue collected 3 and 6 days after infection.

Collectively, hCoV-EMC/2012 caused acute localized-to-widespread pneumonia in all animals, resulting in mild-to-moderate clinical disease. This animal model establishes the causal relationship between hCoV-EMC/2012 and respiratory disease in rhesus macaques reminiscent of the respiratory disease observed in humans, thus fulfilling Koch’s postulates. The model enables detailed studies of the pathogenesis of this illness and may be a critical component in the evaluation of intervention strategies for this newly emerging coronavirus.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C, et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio. 2012;3(6):e00473–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müller MA, Raj VS, Muth D, et al. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. MBio. 2012;3(6):e00515–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00515-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brining DL, Mattoon JS, Kercher L, et al. Thoracic radiography as a refinement methodology for the study of H1N1 influenza in cynomologus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Comp Med. 2010;60:389–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corman VM, Müller MA, Costabel U, et al. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20334. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.49.20334-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]