Abstract

This longitudinal study modeled lexical development among children who spoke Vietnamese as a first language (L1) and English as a second language (L2). Participants (n=33, initial mean age of 7.3 years) completed a total of eight tasks (four in each language) that measured vocabulary knowledge and lexical processing at four yearly time points. Multivariate hierarchical linear modeling was used to calculate L1 and L2 trajectories within the same model for each task. Main findings included (a) positive growth in each language, (b) greater gains in English resulting in shifts toward L2 dominance, and (c) different patterns for receptive and expressive domains. Timing of shifts to L2 dominance underscored L1 skills that are resilient and vulnerable to increases in L2 proficiency.

Many children in the United States learn a minority first language (L1) at home and learn the language of the majority community, English, as a second language (L2) in an school setting such as preschool or kindergarten. Different ages and contexts for learning make minority L1-majority L2 sequential learners a unique population in the investigation of cognitive, social, and linguistic factors in child development. The vast majority of empirical studies measuring the L1 and L2 of bilingual children have focused on Spanish-speaking L1 learners (e.g., Cobo-Lewis, Pearson, Eilers, & Umbel, 2002a, b; Hammer, Lawrence, & Miccio, 2007; Jia, Kohnert, Collado, & Aquino-Garcia, 2006; Kohnert, Bates, & Hernandez, 1999; Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Ordoñez, Carlo, Snow, & McLaughlin, 2002; Peña, Bedore, & Zlatic-Giunta, 2002; Rojas & Iglesias, 2012). Far fewer studies have investigated minority languages in the US other than Spanish such as Chinese (e.g., Jia & Aaronson, 2003) and Hmong (Kan & Kohnert, 2012).

This study focuses on the lexical development of school-age children learning Vietnamese (L1) and English (L2). There are no empirical studies that measure Vietnamese language skills in bilingual learners with the single exception of Pham and Kohnert (2010). The investigation of language pairs that greatly differ in origin and typology contributes to a broader understanding of child language acquisition in diverse circumstances. Children who speak Vietnamese and English navigate two highly contrastive language systems. Although there are a shared set of consonant and vowel sounds, each language has unique phonological characteristics such as consonant blends in English (e.g., “string”) and lexical tones in Vietnamese (e.g., “má” with a rising tone means “cheek”, while “ma” with a level tone means “ghost”; see Tang, 2007, for a detailed cross-language comparison). Unlike language pairs that are more related in typology, English and Vietnamese do not share cognates or words with similar form and meaning (e.g., “elephant” in English and “elefante” in Spanish). English is a moderately inflected language that marks number (e.g., cats) and verb tense (e.g., walked), while Vietnamese is an isolating language that does not use bound morphemes (Tang, 2007). Pragmatically, English is considered “low context” in which communication is based on explicit verbal statements, while Vietnamese, similar to many Asian languages, can be considered “high context” in which communication is heavily dictated by body language, the use of silence, and social status (Hall & Hall, 1976). Studies with children who speak two distinct languages such as Vietnamese and English complement the extensive Spanish-English literature to collectively provide a more comprehensive empirical basis for understanding minority L1–majority L2 bilingualism. Prior to introducing the present study, we begin with a review of L1 and L2 lexical development and current methodological advances in bilingual language acquisition.

L1 and L2 Lexical Skills in School-Age Children

Vocabulary acquisition plays an important role in language development across the life span. During the early school years, children experience rapid increases in vocabulary as a function of home and school experiences, particularly through the onset of literacy (Clark, 1995). Vocabulary knowledge is often measured using standardized expressive and receptive vocabulary tests (e.g., Brownell 2000a, b). Performance on these measures is highly dependent on previous language experiences (Umbel, Pearson, Fernández, & Oller, 1992).

Bilingual children have been found to have different growth patterns for the L1 and L2 during the school-age years due to varying levels of input and educational experience in each language. Oller and Eilers (2002) examined language proficiency in a cross-sectional study with bilingual children in kindergarten, second and fifth grade living in Miami, Florida. Participants spoke Spanish (L1) and English (L2) and were divided into groups based on three independent variables: school programming (L2-only vs. L1 and L2), home language (L1-only vs. L1 and L2) and SES (high vs. low). Participants completed a variety of oral and written language tests, four of which are relevant here: English and Spanish versions of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised (PPVT: Dunn & Dunn, 1981; TVIP: Dunn, Padilla, Lugo, & Dunn, 1986) to measure receptive vocabulary, and English and Spanish versions of the Picture Vocabulary Test from the Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery Revised (Woodcock, 1991; Woodcock & Sandoval, 1996) to measure expressive vocabulary. For receptive vocabulary, participants on average showed high and steady Spanish (L1) skills and made significant gains in English (L2) by grade level; for expressive vocabulary, participants on average showed slow increases in Spanish and relatively more rapid gains in English (Cobo-Lewis et al, 2002a, b). More rapid increases in English contributed to a shift to L2 dominance at Grade 2 with higher average performance in English than Spanish for Grades 2 and 5. High English performance was related to high SES. However, school programming did not affect English outcomes. Participants in school programs with L1 and L2 instruction performed as well in English as participants in English-only programs (Cobo-Lewis, et al, 2002a). High Spanish performance was associated with Spanish-only home language use and L1-L2 school programs (Cobo-Lewis et al., 2002b).

Alongside gains in vocabulary knowledge, school-age children also begin to process lexical information more effectively (Kohnert & Bates, 2002). Measures of lexical processing emphasize efficiency in accessing or using vocabulary knowledge. In contrast to knowledge-based measures, processing-based measures minimize the role of prior experience and consist of stimuli that are equally familiar to all children such as high-frequency words or equally unfamiliar stimuli such as nonsense words (e.g., Kohnert, Windsor, & Yim, 2006).

Kohnert and colleagues conducted a series of cross-sectional studies to examine lexical processing skills in bilinguals (Kohnert et al, 1999; Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Jia, et al, 2006). Participants lived in Southern California and spoke Spanish as their L1 in the home with formal English (L2) experience beginning at age 5. Participants were divided into five age groups: 5 to 7 years, 8 to 10 years, 11 to 13 years, 14 to 16 years, and college age. Lexical processing measures included picture naming (Kohnert et al, 1999; Jia et al, 2006) and picture word verification (Kohnert & Bates, 2002). Stimuli were high frequency objects and actions with accuracy and response time (RT) as the dependent variables. Main findings included positive increases in both languages, relatively greater gains in the L2, and shifts towards L2 dominance as a function of age. Timing of shifts to L2 dominance varied across expressive and receptive modalities. In the receptive modality as measured by picture word verification, children in the youngest three age groups (ages 5 to 10) responded to high frequency items equally well in both languages, but by early adolescence (ages 11+) participants demonstrated a shift towards faster processing speed and higher accuracy in the L2 (Kohnert & Bates, 2002). In the expressive modality as measured by picture naming, a complete shift to L2 dominance (accuracy and RT) came later and was not evident until 14 to 16 years of age (Kohnert et al, 1999; Jia et al, 2006).

Evaluating vocabulary knowledge alongside lexical processing provides a richer description of children’s overall lexical development that includes the amount of words children know and how efficiently they are able to use this knowledge. The present study uses four knowledge-based measures (two in each language) to investigate expressive and receptive vocabulary and four processing-based measures (two in each language) to investigate lexical access and retrieval. There have been no longitudinal studies of lexical development in school-age bilinguals using a combination of knowledge and processing-based tasks. Previous studies have focused solely on lexical knowledge of children learning a single language (e.g., Brownell 2000a, b) or two languages (e.g., Ordoñez et al, 2002). Other studies have focused exclusively on lexical processing skills in a single language (e.g., Dollaghan & Campbell, 1998) or two languages (e.g., Jia et al, 2006). For younger bilingual children, there has been cross-sectional work involving both knowledge-based and processing-based measures (Marchman, Fernald, & Hurtado, 2010). For single language learners, there have been few studies involving both types of lexical measures using cross-sectional (e.g., Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990) and longitudinal designs (e.g., Fernald, Perfors, & Marchman, 2006; Gathercole, Willis, Emslie, & Baddeley, 1992). The present study uses a longitudinal design and incorporates lexical knowledge and processing in order to provide a comprehensive profile of L1-L2 lexical development.

Methodological Advances in Bilingual Language Acquisition

Historically, language studies with minority language children have focused on L2 acquisition. Key research questions consisted of the positive and negative effects of bilingualism on English (L2), educational, and cognitive outcomes (e.g., Ben-Zeev, 1977). Current studies have broadened the focus to include both languages of bilingual children. Within the past three decades, there has been a surge of empirical studies with direct measures of the L1 and L2. Studies have incorporated large cross-sectional designs to compare bilinguals of varying ages (e.g., Kohnert et al, 1999; Kohnert & Bates, 2002) and have examined L1 and L2 performance as a function of educational programming, SES, and language(s) spoken in the home (e.g., Oller & Eilers, 2002). Subsequent longitudinal studies have incorporated two time points to measure within-participant change and highlight individual variability (e.g., Kohnert, 2002) as well as identify potential longitudinal relations between the L1 and L2 (e.g., Uccelli & Páez, 2007).

Within the past five years, empirical studies on bilingual language acquisition have begun to incorporate multiple time points and growth curve modeling (e.g., Hammer et al, 2007; Kan & Kohnert, 2012; Rojas & Iglesias, 2012; Gutierrez-Clellen, Simon-Cereijido, & Sweet, 2012). Growth curve modeling, also referred to as hierarchical linear modeling (HLM: Raudenbush & Bryk, 2001), linear mixed modeling (Long, 2011), or multilevel modeling (Singer & Willett, 2003), has many advantages over traditional repeated measures approaches (e.g., ANOVAs) including the ability to (a) calculate rates of change (i.e., slope) and extrapolate future change, (b) model linear and nonlinear change, (c) include participants who complete varying number of time points, and (d) account for between-subjects and within-subject variability (Long, 2011; Singer & Willett, 2003). The present study contributes to these methodological advances through the use of multivariate longitudinal analysis. Specifically, the present study uses multivariate HLM (Long, 2011; MacCallum, Kim, Malarkey, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1997) to model L1 and L2 response variables within the same model. The statistical advantage of multivariate HLMs is the ability to make direct comparisons between the two response variables (Long, 2011). Models that capture growth of the L1 and L2 within the same model may better reflect the nature of bilingualism in which two languages are nested within individual speakers.

The Present Study

The present study is framed within a dynamic systems approach to development in which a child’s language system emerges through multiple interactions within language (e.g., words vs. grammar) and between social and cognitive systems (Elman, 1995; Lewis, 2003; van Geert, 1998). A dynamic systems approach addresses the basic question of “how does X change over time?” (Smith & Samuelson, 2003) through the use of empirically-derived models of previous developmental states that serve as the basis for positing potential future states (Thelen, Ulrich, & Wolff, 1991; van Geert, 1998). The purpose of this study is to statistically model L1 and L2 lexical growth trajectories among bilingual children. The goal is to determine the relative resiliency or vulnerability of different components of the lexical system to changes in absolute and relative language proficiencies. Based on previous empirical findings with Spanish L1 bilinguals (e.g., Jia et al, 2006; Kohnert et al, 1999; Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Oller & Eilers, 2002), we anticipate (a) positive gains in both languages, (b) relatively more rapid growth in the majority L2, and (c) shifts toward L2 dominance. The timing of the shift to L2 dominance may vary as a function of the type of lexical measure (knowledge vs. processing based) or modality (receptive vs. expressive). Early shifts to L2 dominance would indicate vulnerable skills in the L1, while later shifts would indicate resilient L1 skills in the face of increases in L2 proficiency and use that are characteristic of minority L1 learners acquiring English as the majority L2. We anticipate early shifts to L2 dominance in expressive knowledge-based measures (i.e., expressive vocabulary) based on previous studies that found a shift to L2 dominance by second grade or 7 to 8 years of age (Cobo-Lewis et al, 2002a, b). In contrast, previous studies that used processing-based measures found shifts to the L2 ranging from 11 to 14 years of age (Jia et al, 2006; Kohnert et al, 1999; Kohnert & Bates, 2002). Similar L1 and L2 growth trajectories on processing-based measures would be consistent with interactive theories that point to common cognitive processing substrates for the L1 and L2 (Kohnert, Windsor, & Yim, 2006).

The present study used an accelerated cohort design (Singer & Willett, 2003) in which information was gathered from ages 6 to 11 years (6 year age span) within four years of data collection. The total sample consisted of three age cohorts: Cohort 1 began the study at age 6 years, Cohort 2 at age 7 years, and Cohort 3 at age 8 years. Data collection was completed within a two week time span during the month of January for 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011.

Method

Participants

A total of 33 typically developing school-age children (18 girls) participated in this longitudinal study (mean age at Time 1 was 7.35 years, SD = 0.9). Table 1 displays participant characteristics of the total sample and of Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 separately. Nonparametric tests were used to compare the three cohorts given small sample sizes. Participant characteristics did not differ by cohort based on separate Kruskal-Wallis tests for each independent variable (see Table 1). For the total sample, 18 participants (55%) were born in the US; the average age of immigration to the US for the remaining 15 participants was 3.37 years (SD = 1.9). All participants learned Vietnamese as the L1 beginning at birth and English as the L2 in early childhood. The average age of L2 onset was 4.46 years (SD = 1.3) with the vast majority of participants beginning systemic L2 exposure in preschool or kindergarten. Nineteen participants (58%) qualified for free or reduced lunch at school, an indicator of low SES.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Total Sample n = 33 | Cohort 1 n = 12 | Cohort 2 n = 12 | Cohort 3 n = 9 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at Time 1 in years (SD) | 7.35 (0.9) | 6.45 (0.3) | 7.43 (0.3) | 8.45 (0.5) | --- |

| Females (% sample) | 18 (55%) | 7 (58%) | 6 (50%) | 5 (56%) | .92 |

| Mean TONI-3 standard score (SD) | 111 (13) | 106 (12) | 113 (10) | 114 (19) | .40 |

| Free or reduced lunch (% sample) | 19 (58%) | 6 (50%) | 7 (58%) | 6 (67%) | .75 |

| U.S. born (% sample) | 18 (55%) | 8 (67%) | 5 (42%) | 5 (56%) | .45 |

| Age of U.S. arrival in years (SD) | 3.37 (1.9) | 3.33 (1.5) | 3.00 (1.8) | 4.75 (2.5) | .43 |

| Age of English (L2) onset in years | 4.46 (1.3) | 4.30 (1.1) | 4.56 (1.1) | 4.60 (2.1) | .54 |

Note. Age of U.S. arrival is reported for participants born outside of the US. Age of L2 onset is based on parent report and includes all participants. P-values correspond to separate nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests for each independent measure to compare Cohorts 1, 2, and 3. TONI-3 =Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, 3rd edition (Brown, Sherbenou, & Johnsen, 1997).

Based on responses from individually administered interview questions, participants reported high proficiency in both of their languages. Nearly all children reported understanding Vietnamese (93%) and English (97%) “well” or “very well” and speaking Vietnamese (93%) and English (93%) “well” or “very well”. Nearly all participants (97%) reported speaking only Vietnamese to parents and grandparents; Vietnamese and English (40%) or mainly Vietnamese (32%) to siblings; and Vietnamese and English (41%) or only English (35%) to friends. On written questionnaires, parents reported that children used Vietnamese and English approximately the same amount of time in their daily lives and spoke both languages either “well” or “very well”. Most children (84%) lived with both parents, had siblings (74%) and many children had at least one grandparent living at home (39%).

All participants scored within one standard deviation of the published mean or higher on the Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, 3rd edition, (TONI-3:Brown, Sherbenou, & Johnsen, 1997) with a mean standard score of 111 (SD = 13) and range from 85 to 140. School records indicated that all children passed vision and hearing screenings at the beginning of each year. Children were excluded from the study if they had lived in the US for less than one year, or had documented hearing, cognitive, neurological, language or learning impairments. Additionally, in the absence of normative data on Vietnamese populations, children were excluded from participation if a teacher or parent expressed concern regarding the child’s language development or academic achievement (cf. Restrepo, 1998).

General Study Design and Procedures

Children were recruited to participate in this study from a single public elementary school (kindergarten through fifth grade) in an urban area in the Southeastern United States in which Vietnamese American children comprised approximately 20% of the total student population. Although English was the primary language of instruction, participants also received 90 minutes per day of heritage language and literacy instruction in Vietnamese as part of a transitional program for English language learners. Vietnamese language classes mirrored English language classes in content with the focus on building literacy skills (e.g., students read and wrote about Martin Luther King day in both English and Vietnamese language classes: H.A. Nguyen, personal communication, January 6, 2009). The Vietnamese language program was open to students throughout the school district. Most Vietnamese American children who attended this school did not live in the neighborhood but rather traveled by bus for commutes as long as one hour away (H.A. Nguyen, personal communication, January 6, 2009). Participants were recruited from two Vietnamese language classes taught by the same teacher. The morning class consisted of children in kindergarten and first grade. The afternoon class consisted of children in first and second grades. Within a given academic year, total enrollment in the two classes ranged from 30 to 45 students. (A second Vietnamese language teacher who taught grades 3 to 5 was not directly involved in recruitment but helped with scheduling sessions for her students to participate in follow-up years.) Study recruitment consisted of fliers written in Vietnamese that were sent home via students’ class folders and follow-up phone calls by the Vietnamese language teacher to answer any further questions. The positive response rate was nearly 100% given the well-established trusting relationship between the Vietnamese teacher and parents. Participants completed the informed consent process annually to ensure parents understood that their child would participate in the same study over multiple years. Individual results were summarized in Vietnamese and mailed home to families after each year’s data collection. Group findings were presented to the school principal and teachers at faculty meetings and written reports.

Participants completed the same language tasks in Vietnamese (L1) and in English (L2) at each yearly time point. Experimental tasks were administered individually in a quiet room in the children’s school or home by trained examiners who were native speakers of Vietnamese or English. Languages were separated by examiner, and the first language of administration was counterbalanced across participants; at each time point, half the children were tested first in Vietnamese and half the children were tested first in English.

Lexical tasks

Participants completed a total of eight language tasks, four in each language. The following is a description of two tasks based on vocabulary knowledge and two tasks based on lexical processing.

Knowledge-based tasks

Knowledge-based tasks consisted of items from standardized vocabulary tests: Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th edition (ROWPVT: Brownell, 2000b) and Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th edition (EOWPVT: Brownell, 2000a). Tests were originally standardized for monolingual English-speaking children ages 4 to 13 years to measure breadth of knowledge from basic to advanced academic vocabulary. Because these tests have not been standardized for Vietnamese-English bilinguals, all participants completed the same set of items rather than following the recommended starting and ending points. Items were translated into Vietnamese by the first author using an online dictionary (vdict.com) and at a later time point back-translated into English (cf. Peña, 2007).

Receptive vocabulary

This task consisted of items from the ROWPVT in which an array of four pictures were presented, and participants were asked to identify the picture corresponding to the target word item. Sixty items were originally selected within the age range of 5 to 11 years to include advanced vocabulary such as “parallel,” “competitive,” and “octagon”. Twelve items that did not have clear one-to-one translation equivalents were omitted (e.g., the Vietnamese translation of “slumber” was giấc ngủ, which back-translates as both “sleep” and “slumber”). The dependent measure was percent of items correctly identified out of 48 total. These tasks showed adequate to good internal consistency in this sample at Time 1 with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 for the Vietnamese measure and 0.84 for the English measure.

Expressive vocabulary

This task consisted of items from EOWPVT in which participants were asked to name items depicted in pictures. Sixty items were selected within the age range of 5 to 11 years to include advanced vocabulary such as “microscope,” “measuring,” and “percentage”. Seventeen items were omitted in the translation process that did not have clear one-to-one translation equivalents (e.g., the word “hoof” was translated as bàn chân, which was back-translated as “foot”). The dependent measure was percent of items correctly named out of 43 total. These tasks showed good internal consistency in this sample at Time 1 with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 for the Vietnamese measure and 0.92 for the English measure.

Processing-based tasks

The two processing-based tasks, Picture Word Verification (PWV) and Picture Naming, shared a set of common features. Stimuli for both tasks consisted of high frequency objects and actions depicted in black-and-white line drawings from the International Picture Naming Project (Szekely et al., 2004). Items were equated by word frequency using language corpora in Vietnamese (Pham, Kohnert, & Carney, 2008) and English (Baayen, Piepenbrock, & Gulikers, 1995). For each task, stimuli were presented in a set of 40 pictured objects followed by a set of 40 pictured actions with 8 training items and 3 practice items before each set. Separate Vietnamese and English tasks used the same items presented in a different order. There were no overlapping items between PWV and Picture Naming.

Both tasks were administered using E-Prime 2.0 computer software to capture response time (RT) in milliseconds. RTs were individually trimmed for each participant, in each language, separately for objects and actions so that RTs ± 2 SDs from each child’s mean was omitted. Spurious RTs were also omitted, defined as either < 50 ms or > 5000 ms for PWV and items in which the microphone malfunctioned and/or RTs were less than < 50 ms for Picture Naming. Less than 3% of the data were omitted using these criteria. Composite RTs, one for each language, reflected the average response time across object and action stimuli.

Picture word verification

PWV provided an index of receptive lexical processing skills by measuring the accuracy and speed with which children confirmed or rejected picture-word correspondences (cf. Kohnert & Bates, 2002). Participants saw a picture appear on a computer screen and listened to a word presented via headphones; they were instructed to press one of two buttons on a response box with the index finger of their dominant hand to indicate whether a picture and spoken word were congruent (e.g., a picture of a chair paired with the spoken word “chair”) or incongruent (e.g., a picture of a table paired with the word “chair”). Within each set of 40 objects and 40 actions, 20 items were congruent and 20 items were incongruent. The order of items was block randomized with congruency alternating on every first, second, or third trial. The first author (female voice, fluent in Vietnamese and English) digitally audio-recorded each word item in both languages in a soundproof booth using natural speech intonation. Dependent measures were accuracy and RT. Accuracy was the number of objects and actions correctly identified in the congruent condition and was calculated as percent correct (out of 40 total). As is conventional, RTs were measured solely for accurate responses and defined as the time between the presentation of the picture and word stimuli and child response. Using accuracy as the dependent measure, the English measure showed good internal consistency in this sample at Time 1 with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. The Vietnamese measure showed poor internal consistency based on a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.66. However, the reliability coefficient for the Vietnamese task may have underestimated the internal consistency of the sample’s responses given the high number of items with zero variance (i.e., items in which all participants responded correctly). For example, 21 of 80 Vietnamese items had zero variance compared to 9 of 80 items in English. Participants performed at ceiling levels in accuracy for the Vietnamese measure at Time 1, which may have artificially lowered Cronbach’s alpha.

Picture naming

Picture naming measured expressive lexical processing skills, specifically, the ability to access, retrieve, and generate high frequency lexical items (cf. Kohnert et al, 1999; Jia et al, 2006). This task measured how quickly and accurately participants were able to use their vocabulary knowledge in a “real-time” situation. Individual participants wore a microphone headset and sat next to the examiner in front of a computer. An “X” appeared on the computer screen to indicate that a picture would appear. Once the picture appeared, participants named the picture as quickly as possible. Once the microphone detected a sound, a blank screen with the word “more?” appeared (or thêm? in Vietnamese), and the examiner clicked the mouse to continue to the next trial. Dependent measures were accuracy and RT. Accuracy reflected the number of objects and actions correctly named and was calculated as percent correct (out of 80 total). RT was defined as the time between the onset of the picture and the onset of the spoken word for correctly named items. Using accuracy as the dependent measure, these tasks showed good internal consistency in this sample at Time 1 with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 for the Vietnamese measure and 0.95 for the English measure.

Study Attrition

Participants completed a minimum of one time point and a maximum of four yearly time points of language testing. Tables 2 and 3 display the number of participants at each time point for the total sample and by cohort. The attrition rate over the four-year enrollment period was 64% for the total sample, 75% for Cohort 1, 50% for Cohort 2, and 67% for Cohort 3. These attrition rates, although seemingly high, were comparable to previous language studies with bilingual children living in the US. For example, Kohnert (2002) reported an attrition rate of 47% in a follow up study with school-age bilingual children after a single year. Restrepo and colleagues (2012) conducted a language treatment study with bilingual preschoolers and reported an average attrition rate of 44% within a 20-month time period.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Vietnamese (L1)

| Total Sample | Time 1 (n = 33) | Time 2 (n = 27) | Time 3 (n = 21) | Time 4 (n = 12) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

| Age | 7.35 | 0.9 | 6.00 – 9.25 | 8.31 | 0.8 | 7.00 – 10.00 | 9.13 | 0.8 | 8.00 – 10.92 | 10.53 | 0.7 | 9.58 – 11.92 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 62 | 11 | 40 – 85 | 69 | 11 | 48 – 96 | 75 | 12 | 42 – 94 | 83 | 9 | 63 – 92 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 30 | 12 | 2 – 65 | 34 | 11 | 19 – 63 | 34 | 12 | 19 – 70 | 42 | 13 | 21 – 67 |

| PWV ACC | 93 | 5 | 83 – 100 | 95 | 5 | 75 – 100 | 97 | 4 | 88 – 100 | 98 | 2 | 95 – 100 |

| PWV RT | 1429 | 310 | 967 – 2211 | 1191 | 240 | 781 – 1635 | 1063 | 224 | 811 – 1722 | 915 | 117 | 737 – 1178 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 72 | 10 | 53 – 91 | 77 | 9 | 58 – 94 | 77 | 10 | 61 – 91 | 82 | 10 | 61 – 94 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1363 | 382 | 796 – 3125 | 1279 | 232 | 883 – 1832 | 1187 | 204 | 855 – 1575 | 1040 | 188 | 786 – 1312 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cohort 1 | Time 1 (n = 12) | Time 2 (n = 10) | Time 3 (n = 10) | Time 4 (n = 3) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | 6.45 | 0.3 | 6.00 – 6.83 | 7.50 | 0.3 | 7.00 – 7.83 | 8.42 | 0.3 | 8.00 – 8.83 | 9.75 | 0.1 | 9.58 – 9.83 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 55 | 8 | 40 – 71 | 61 | 9 | 48 – 75 | 68 | 11 | 42 – 79 | 75 | 11 | 63 – 83 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 23 | 11 | 2 – 40 | 26 | 5 | 19 – 33 | 27 | 6 | 19 – 35 | 31 | 9 | 21 – 37 |

| PWV ACC | 91 | 5 | 83 – 100 | 93 | 8 | 75 – 100 | 95 | 4 | 88 – 100 | 98 | 1 | 98 - 98 |

| PWV RT | 1601 | 391 | 1074 – 2211 | 1233 | 239 | 918 – 1635 | 1096 | 282 | 811 – 1722 | 829 | 82 | 737 – 893 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 65 | 8 | 53 – 79 | 72 | 8 | 63 – 84 | 73 | 10 | 61 – 85 | 81 | 5 | 76 – 86 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1334 | 165 | 1120 – 1657 | 1207 | 196 | 984 – 1470 | 1188 | 198 | 972 – 1575 | 935 | 137 | 854 – 1093 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cohort 2 | Time 1 (n = 12) | Time 2 (n = 11) | Time 3 (n = 7) | Time 4 (n = 6) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | 7.43 | 0.3 | 7.00 – 7.83 | 8.43 | 0.3 | 8.00 – 8.83 | 9.43 | 0.3 | 9.00 – 9.83 | 10.50 | 0.3 | 10.17 – 10.83 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 64 | 12 | 44 – 85 | 71 | 10 | 60 – 96 | 82 | 8 | 75 – 94 | 85 | 7 | 73 – 90 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 34 | 12 | 21 – 65 | 34 | 11 | 26 – 63 | 39 | 15 | 23 – 70 | 44 | 12 | 33 – 67 |

| PWV ACC | 95 | 4 | 88 – 100 | 96 | 3 | 93 – 100 | 98 | 4 | 90 – 100 | 98 | 2 | 95 – 100 |

| PWV RT | 1395 | 198 | 1141 – 1733 | 1184 | 226 | 864 – 1582 | 1039 | 201 | 835 – 1444 | 966 | 120 | 848 – 1178 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 75 | 7 | 68 – 88 | 78 | 10 | 58 – 94 | 80 | 8 | 66 – 90 | 81 | 13 | 61 – 94 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1406 | 597 | 796 – 3125 | 1260 | 228 | 883 – 1633 | 1141 | 239 | 855 – 1528 | 1060 | 210 | 786 – 1312 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cohort 3 | Time 1 (n = 9) | Time 2 (n = 6) | Time 3 (n = 4) | Time 4 (n = 3) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | 8.45 | 0.5 | 8.00 – 9.25 | 9.43 | 0.4 | 9.00 – 10.00 | 10.40 | 0.4 | 10.08 – 10.92 | 11.39 | 0.5 | 11.08 – 11.92 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 69 | 8 | 58 – 83 | 79 | 9 | 67 – 90 | 81 | 11 | 65 – 90 | 88 | 5 | 83 – 92 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 35 | 9 | 23 – 47 | 44 | 12 | 30 – 58 | 43 | 11 | 33 – 58 | 50 | 12 | 37 – 60 |

| PWV ACC | 94 | 5 | 85 – 100 | 98 | 2 | 95 – 100 | 100 | 1 | 98 – 100 | 98 | 3 | 95 – 100 |

| PWV RT | 1243 | 188 | 967 – 1547 | 1132 | 293 | 781 – 1529 | 1022 | 82 | 926 – 1122 | 900 | 114 | 777 – 1003 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 80 | 8 | 70 – 91 | 85 | 4 | 78 – 90 | 84 | 8 | 75 – 91 | 88 | 8 | 79 – 93 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1344 | 225 | 1078 – 1758 | 1437 | 257 | 1066 – 1832 | 1266 | 183 | 1100 – 1442 | 1105 | 203 | 905 – 1312 |

Note. Means, standard deviations, and ranges displayed for the total sample and Cohorts 1, 2, and 3. PWV = Picture word verification; ACC = Accuracy in percent correct; RT = Response time in milliseconds.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for English (L2)

| Total Sample | Time 1 (n = 33) | Time 2 (n = 27) | Time 3 (n = 21) | Time 4 (n = 12) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

| Age | 7.35 | 0.9 | 6.00 – 9.25 | 8.31 | 0.8 | 7.00 – 10.00 | 9.13 | 0.8 | 8.00 – 10.92 | 10.53 | 0.7 | 9.58 – 11.92 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 55 | 14 | 27 – 88 | 67 | 16 | 33 – 98 | 75 | 13 | 48 – 94 | 87 | 7 | 71 – 96 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 28 | 19 | 0 – 60 | 35 | 19 | 0 – 70 | 50 | 19 | 16 – 81 | 64 | 14 | 33 – 84 |

| PWV ACC | 92 | 7 | 63 – 100 | 95 | 7 | 63 – 100 | 95 | 5 | 80 – 100 | 98 | 2 | 93 – 100 |

| PWV RT | 1399 | 363 | 856 – 2293 | 1153 | 209 | 883 – 1836 | 1112 | 308 | 807 – 2216 | 858 | 76 | 760 – 953 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 66 | 16 | 13 – 89 | 76 | 13 | 33 – 94 | 83 | 12 | 45 – 98 | 90 | 5 | 80 – 98 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1120 | 218 | 746 – 1631 | 1051 | 203 | 742 – 1559 | 1049 | 158 | 788 – 1358 | 827 | 102 | 653 – 981 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cohort 1 | Time 1 (n = 12) | Time 2 (n = 10) | Time 3 (n = 10) | Time 4 (n = 3) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | 6.45 | 0.3 | 6.00 – 6.83 | 7.50 | 0.3 | 7.00 – 7.83 | 8.42 | 0.3 | 8.00 – 8.83 | 9.75 | 0.1 | 9.58 – 9.83 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 48 | 9 | 29 – 60 | 53 | 12 | 33 – 69 | 69 | 15 | 48 – 92 | 78 | 6 | 71 – 83 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 15 | 9 | 0 – 35 | 19 | 13 | 0 – 40 | 37 | 16 | 16 – 63 | 52 | 17 | 33 – 63 |

| PWV ACC | 87 | 9 | 63 – 98 | 92 | 10 | 63 – 98 | 94 | 6 | 80 – 98 | 96 | 2 | 95 – 98 |

| PWV RT | 1599 | 405 | 942 – 2293 | 1239 | 297 | 924 – 1836 | 1185 | 412 | 858 – 2216 | 820 | 65 | 760 – 890 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 54 | 17 | 13 – 75 | 66 | 16 | 33 – 83 | 76 | 13 | 45 – 86 | 84 | 4 | 80 – 88 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1184 | 157 | 933 – 1446 | 1086 | 262 | 742 – 1559 | 1036 | 151 | 788 – 1230 | 738 | 89 | 653 – 831 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cohort 2 | Time 1 (n = 12) | Time 2 (n = 11) | Time 3 (n = 7) | Time 4 (n = 6) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | 7.43 | 0.3 | 7.00 – 7.83 | 8.43 | 0.3 | 8.00 – 8.83 | 9.43 | 0.3 | 9.00 – 9.83 | 10.50 | 0.3 | 10.17 – 10.83 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 52 | 17 | 27 – 88 | 70 | 9 | 56 – 88 | 78 | 7 | 69 – 90 | 90 | 3 | 85 – 94 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 29 | 19 | 5 – 60 | 40 | 16 | 14 – 67 | 56 | 15 | 30 – 81 | 66 | 11 | 53 – 84 |

| PWV ACC | 93 | 4 | 88 – 100 | 95 | 4 | 90 – 100 | 96 | 4 | 90 – 100 | 98 | 3 | 93 – 100 |

| PWV RT | 1393 | 305 | 1001 – 2068 | 1114 | 106 | 946 – 1281 | 1084 | 150 | 845 – 1199 | 864 | 79 | 765 – 953 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 68 | 11 | 51 – 85 | 79 | 7 | 69 – 94 | 87 | 4 | 83 – 94 | 91 | 3 | 86 – 95 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1080 | 227 | 758 – 1631 | 991 | 129 | 837 – 1180 | 1034 | 158 | 835 – 1234 | 828 | 90 | 717 – 976 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cohort 3 | Time 1 (n = 9) | Time 2 (n = 6) | Time 3 (n = 4) | Time 4 (n = 3) | ||||||||

| M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | M | SD | Range | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age | 8.45 | 0.5 | 8.00 – 9.25 | 9.43 | 0.4 | 9.00 – 10.00 | 10.40 | 0.4 | 10.08 – 10.92 | 11.39 | 0.5 | 11.08 – 11.92 |

| Receptive Vocabulary | 66 | 9 | 54 – 75 | 86 | 11 | 73 – 98 | 86 | 8 | 75 – 94 | 90 | 8 | 81 – 96 |

| Expressive Vocabulary | 44 | 15 | 16 – 60 | 53 | 14 | 30 – 70 | 69 | 8 | 56 – 74 | 71 | 13 | 58 – 84 |

| PWV ACC | 96 | 4 | 88 – 100 | 98 | 2 | 95 – 100 | 98 | 2 | 95 – 100 | 99 | 1 | 98 – 100 |

| PWV RT | 1142 | 201 | 856 – 1490 | 1082 | 152 | 883 – 1280 | 978 | 190 | 807 – 1152 | 884 | 90 | 780 – 941 |

| Picture Naming ACC | 79 | 8 | 64 – 89 | 86 | 4 | 78 – 90 | 93 | 4 | 90 – 98 | 95 | 3 | 93 – 98 |

| Picture Naming RT | 1088 | 275 | 746 – 1544 | 1100 | 210 | 818 – 1367 | 1109 | 203 | 924 – 1358 | 914 | 75 | 833 – 981 |

Note. Means, standard deviations, and ranges displayed for the total sample and Cohorts 1, 2, and 3. PWV = Picture word verification; ACC = Accuracy in percent correct; RT = Response time in milliseconds.

To assess the potential effects of attrition in the current study, we compared participant characteristics between the group of children who completed the maximum number of four yearly time points (n = 12) and the group of children who completed fewer time points (n = 22). Using separate Wilcoxon rank sum tests for each independent measure, we found no group differences in gender (p = .31), birthplace (p = .76), TONI-3 scores (p = .61), age at Time 1 (p = .29), age of U.S. arrival (p = .51), age of L2 onset (p = .29) or whether participants were eligible or not for reduced lunch (p = .44). The primary reason for attrition for the current study was that children moved out of the school district and could not be contacted. Consistent with Widaman (2006) and results from our preliminary tests of attrition, missing data were considered missing at random and were accounted for using maximum likelihood estimation.

Data Analysis

We used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to estimate participants’ initial levels of performance (i.e., intercept) and rates of change over time (i.e., slope). Given that participant ages at the start of the study ranged from 6.0 to 9.3 years, the time metric, age, was centered on the youngest participant in order for the intercept to represent initial language performance for all children at age 6.0 years (rather than all children at age 0). HLM analyses were conducted using the lmer() function in the lme4 package (Bates, 2005) of the R software program.

In a preliminary analysis of the data, we examined the shape of change for each dependent measure using a taxonomy of seven first-order fractional polynomial transformations of the time variable, age, based on procedures outlined in Long and Ryoo (2010). Fractional polynomials are recommended over conventional polynomial transformations (e.g., quadratic, cubic) for samples with relatively few waves of data collection to maximize efficiency and minimize the number of parameters required to model nonlinear change (Long & Ryoo, 2010). Designation of the shape of change was based on two explicit biases towards (a) linearity for parsimony if linear and nonlinear models had similar fit, and (b) fitting the same models for both languages in order to fit later multivariate HLMs. Consistent with Long and Ryoo (2010), the number of models was first narrowed down from seven to three models based on smaller values of fit indices (AIC, BIC, -2LL) and larger effect sizes (R2 and adjusted R2). Based on the original criteria, the linear model was highlighted as a candidate for all dependent measures along with nonlinear models such as logarithmic and inverse square transformations. Second, graphic comparisons for each dependent measure with superimposed regression and smoothed curves showed that the nonlinear curve did not greatly differ from the linear curve (cf. Long & Ryoo, 2010). Therefore, the linear model was selected for all dependent measures.

The main set of analyses consisted of constructing multivariate HLMs (Long, 2011; MacCallum, Malarkey, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1997) to model L1 and L2 performance on each task within a single model (e.g., Vietnamese and English percent correct for Expressive Vocabulary). As outlined in Long (2011), random effects were first added to the model in a step-up fashion. The inclusion of random intercepts was based on inferential testing of whether the variance of each random intercept was greater than zero using fast bootstrapping (Crainiceanu & Ruppert, 2004) in the RLRsim package in R (Scheipl, Greven, & Küchenhoff, 2008). Random intercepts with corresponding p-values < .05 were retained. Then, inferential testing for random slopes included analytical likelihood ratio tests (LRT) and AIC weights of evidence to compare pairs of full and reduced models with (a) random intercepts only, (b) random intercepts and one random slope, and (c) random intercepts and two random slopes (Long, 2011). We selected the best-fitting model based on converging evidence of the largest AIC weight and the results of the LRTs (i.e., p < .05). Nonsignificant random intercepts were included in the final model if the corresponding random slopes were significant as lower-order effects were needed when higher-order effects were significant (Long, 2011).

With random effects included in the multivariate model, the main focus of analysis was fixed effects. First, fixed slopes were tested for equality in order to test whether Vietnamese and English had the same rate of change. The full model with two fixed intercepts and two fixed slopes was compared to a reduced model of two fixed intercepts and one fixed slope (cf. Long, 2011). Second, fixed intercepts were tested for equality to assess whether initial performance was the same for Vietnamese and English. The full model with two fixed intercepts and two fixed slopes was compared to a reduced model with one fixed intercept and two fixed slopes (cf. Long, 2011). For fixed effects, selection of the best-fitting model was based on converging evidence of the largest AIC weight and the results of LRTs (i.e., p < .05).

Results

Tables 2 and 3 display descriptive statistics for all dependent measures in Vietnamese and English, respectively, for the total sample and by cohort. Receptive Vocabulary, Expressive Vocabulary, Picture Word Verification Accuracy (PWV ACC), and Picture Naming ACC increased over the four years in Vietnamese and English. Similarly, PWV RT and Picture Naming RT were faster each year in both languages. The general pattern of increased accuracy and faster RT was reflected within participants over time as well as between cohorts as a function of age (e.g., participants in Cohort 3 who started the study at age 8 years performed better than participants in Cohort 2 who started the study at age 7 years). Participants reached ceiling levels for PWV ACC with mean values ranging from 93 to 98% in Vietnamese and 92 to 98% in English across time points for the total sample. Therefore RT was the main variable of focus for PWV.

Table 4 displays estimates of fixed effects for six separate multivariate HLMs with Vietnamese and English as the two response variables for Receptive Vocabulary, Expressive Vocabulary, PWV ACC, PWV RT, Picture Naming ACC, and Picture Naming RT. The best fitting model for Receptive Vocabulary contained separate fixed intercepts and slopes for each language. As shown in Table 4, participants on average showed greater initial performance in Vietnamese (53%) than English (42%); however, the rate of change was faster rate in English (+10%/year) than Vietnamese (+7%/year).

Table 4.

Vietnamese and English Developmental Trajectories

| Fixed Effect | Vietnamese

|

English

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Z-score | Estimate | SE | Z-score | |

| Receptive Vocabulary | ||||||

| Intercept | 52.55* | 2.05 | 25.67 | 41.80* | 2.16 | 19.32 |

| Slope | 6.90* | 0.71 | 9.71 | 10.16* | 0.74 | 13.79 |

|

| ||||||

| Expressive Vocabulary | ||||||

| Intercept | 26.10* | 2.22 | 11.75 | 11.78* | 2.59 | 4.55 |

| Slope | 2.58* | 0.65 | 3.99 | 11.38* | 0.66 | 17.13 |

|

| ||||||

| Picture Word Verification ACC | ||||||

| Intercept | 91.30* | 1.07 | 85.30 | 89.58* | 1.57 | 56.91 |

| Slope | 1.56* | 0.31 | 5.01 | 2.02* | 0.44 | 4.61 |

|

| ||||||

| Picture Word Verification RT | ||||||

| Intercept | 1608.71* | 51.36 | 31.32 | 1602.58* | 54.24 | 29.55 |

| Slope | −167.29* | 15.82 | −10.58 | −172.52* | 16.31 | −10.58 |

|

| ||||||

| Picture Naming ACC | ||||||

| Intercept | 67.94* | 1.74 | 39.12 | 57.35* | 2.93 | 19.58 |

| Slope | 3.24* | 0.53 | 6.14 | 8.05* | 0.77 | 10.45 |

|

| ||||||

| Picture Naming RT | ||||||

| Intercept | 1461.20* | 60.98 | 23.96 | 1210.72* | 47.36 | 25.57 |

| Slope | −78.14* | 17.48 | −4.47 | −68.46* | 16.17 | −4.23 |

Note. Estimates based on multivariate models with Vietnamese and English as the two response variables. Boldface denotes significantly greater values (or faster for RT) between the two languages.

An asterisk (*) denotes values that are significantly different from zero (p < .05, corresponding to a z-score of ±1.96). ACC = accuracy; RT = response time.

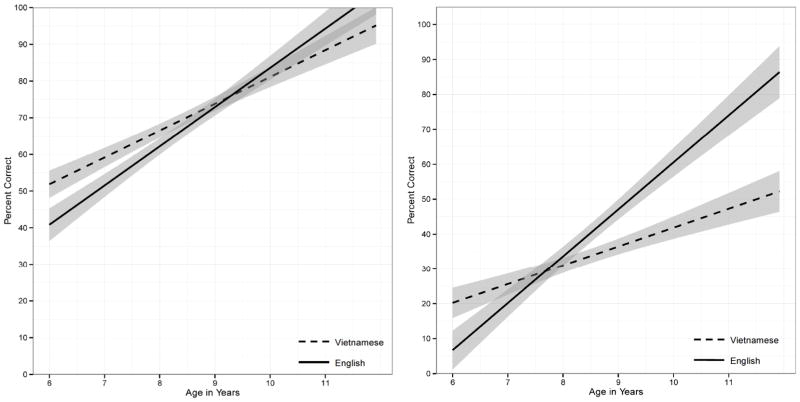

The final model for Expressive Vocabulary contained separate fixed intercepts and slopes for each language. As shown in Table 4, participants on average showed greater initial performance in Vietnamese (26%) than English (12%); however, the rate of change was nearly four times as great for English (+11%/year) as compared to Vietnamese (+3%/year). Figure 1 displays group level trajectories of receptive and expressive vocabulary for Vietnamese (L1) and English (L2). Group level trajectories showed greater accuracy on the receptive tasks than on the expressive tasks for the L1 and L2. In addition, a shift from L1 to L2 dominance that occurred before the age of 8 years for Expressive Vocabulary; the shift towards L2 dominance was not as clear in the receptive modality as demonstrated by overlapping standard error for L1 and L2 Receptive Vocabulary (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Group-level trajectories of Receptive Vocabulary (left) and Expressive Vocabulary (right) for Vietnamese and English based on multivariate models with the two languages as response variables and age as the predictor. Standard errors for group trajectories are shaded gray. For receptive and expressive vocabulary measures, Vietnamese and English were unequal in intercepts and slopes. See Table 4 for estimates of fixed effects.

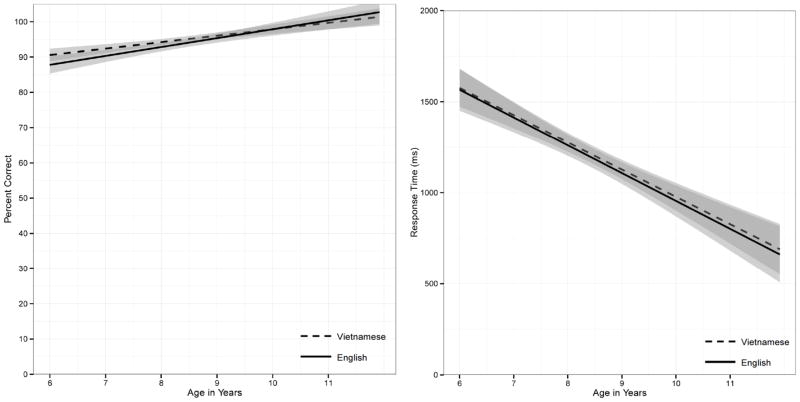

The final model for PWV ACC contained one fixed intercept and one fixed slope for both languages. As shown in Table 4, there was no statistical difference in initial performance (~ 90% correct) or rate of change (~ 2%/year) between the two languages. Similarly, the final model for PWV RT showed no cross-language difference in initial performance (~ 1606 ms) or rate of change (−170 ms/year). Figure 2 displays group level trajectories for the L1 and L2 on PWV ACC and RT. Participants on average were equally as accurate and fast in both languages: Accuracy was at ceiling levels, and the rate of change for L1 and L2 RT decreased (became faster) with age.

Figure 2.

Group-level trajectories of Picture Word Verification accuracy (ACC: left) and response time (RT: right) for Vietnamese and English based on multivariate models with the two languages as response variables and age as the predictor. Standard errors for group trajectories are shaded gray. For ACC and RT, Vietnamese and English were equal in both intercepts and slopes. See Table 4 for estimates of fixed effects.

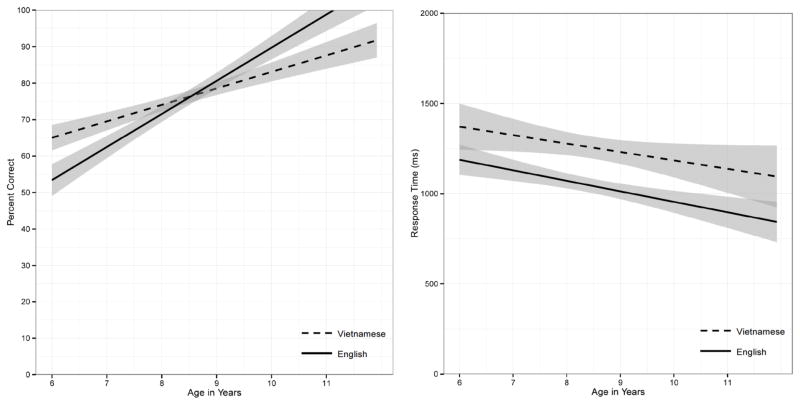

The final model for Picture Naming ACC contained separate fixed intercepts and slopes for each language. As shown in Table 4, Picture Naming ACC was initially higher in Vietnamese (68%) than in English (57%); however, it improved at more than twice the rate in English (+8%/year) as compared to Vietnamese (+3%/year). The final model for Picture Naming RT contained separate fixed intercepts for each language but the same slope. As shown in Table 4, Picture Naming RT showed an English (L2) advantage at initial performance (Vietnamese = 1461 ms; English = 1211 ms) that was maintained over time with steady and comparable RT gains in each language (approximately −73 ms/year). Figure 3 displays L1 and L2 trajectories for Picture Naming ACC and RT. Participants on average showed a shift towards L2 dominance before 9 years of age for ACC, and an L2 advantage in RT from the onset at 6 years of age.

Figure 3.

Group-level trajectories of Picture Naming accuracy (ACC: left) and response time (RT: right) for Vietnamese and English based on multivariate models with the two languages as response variables and age as the predictor. Standard errors for group trajectories are shaded gray. For ACC, Vietnamese and English were unequal in both intercepts and slopes. For RT, Vietnamese and English intercepts were unequal, while slopes were equal. See Table 4 for estimates of fixed effects.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate lexical development in school-age children learning Vietnamese (L1) and English (L2). Participants completed four lexical tasks in each language that measured vocabulary knowledge and lexical processing at four yearly time points. L1 and L2 developmental trajectories were statistically modeled to examine absolute and relative change over time.

Findings from this study highlight three general patterns of L1 and L2 development: (a) positive growth in both languages, (b) relatively greater gains in the L2, and (c) shifts in dominance from the L1 to the L2 over time. Participants on average acquired new vocabulary in both languages and became more efficient at using their vocabulary knowledge. Positive growth may be attributed to continued input and school support for the L1 and L2 (Cobo-Lewis et al, 2002) as well as maturation of cognitive underpinnings for language such as speed of processing (Kail, 1991). Children in this study received daily Vietnamese language instruction as part of their school curriculum. Study findings support conclusions from previous studies that report better L1 outcomes for students in bilingual school programs as compared to English-only programs (Cobo-Lewis et al, 2002; for meta-analysis, see Rolstad, Mahoney, & Glass, 2005). From a dynamic systems approach to development, positive growth in the L1 and L2 may reflect a cooperative relation between the two languages in that growth in one language facilitates growth in the other (van Geert, 1998). Particularly for two highly distinct languages such as Vietnamese and English, future studies on the presence and nature of cross-language interactions are needed to test whether increases in the L1 account for unique variance in L2 development (see Uccelli & Paez, 2007, for example with Spanish-English bilinguals).

Relatively more rapid gains in the L2 may reflect greater levels of L2 input, emphasis on L2 literacy during the early school years, and high social value for the majority language; as children grow up in the US, opportunities to use the L2 for social, educational, and vocational purposes increase substantially (Pearson, 2007). The general patterns of L1 and L2 were consistent with previous empirical studies with bilingual children who speak Spanish as the L1 (Cobo-Lewis et al, 2002a, b; Kohnert et al, 1999; Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Jia et al, 2006). As predicted, the most dramatic differences between L1 and L2 growth curves were observed for Expressive Vocabulary, a knowledge-based measure of advanced vocabulary. The rate of change for the L2 was nearly four times greater than the rate of change for the L1 (11% vs. 3%/year). Consistent with Cobo-Lewis and colleagues (2002a, b), participants on average exhibited a shift to L2 dominance at 8 years of age (see Figure 1).

For the processing-based expressive task, Picture Naming, the timing of the shift to L2 dominance was much earlier for participants in this study as compared to previous studies with Spanish-English bilinguals (Kohnert et al, 1999; Jia et al, 2006). In this study, participants on average showed shifts to L2 dominance as young as 6 years of age for RT and 8 years of age for accuracy (see Figure 3). Using similar object and action naming tasks, Kohnert et al (1999) and Jia et al (2006) did not find complete shifts to the L2 in accuracy and RT until after 14 years of age. Differences in timing could be related to methodological differences (i.e., cross-sectional vs. longitudinal design). It was noted that average L2 onset was consistent across studies at 4 to 5 years of age. Similar overall patterns of L1 and L2 growth and shifts towards L2 dominance across studies lend support to the robustness of general L1 and L2 growth patterns and meaningful differences in timing of L2 shifts.

Earlier shifts to the L2 may reflect socio-linguistic differences between Vietnamese-English and Spanish-English bilinguals. Participants in Kohnert et al (1999) and Jia et al (2006) lived in California where Hispanics comprise nearly 40% of the state population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Children lived in concentrated contexts where Spanish (L1) was consistently used within the larger community. In contrast, participants in the present study lived in Orlando, Florida, where the Vietnamese American population comprised less than 0.5% of the state population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Children lived in disperse communities where Vietnamese (L1) was infrequently used in the larger community. Linguistic isolation may have contributed to earlier shifts to L2 dominance for children in this study despite the fact that they received educational support for the L1. Ethnically concentrated vs. disperse contexts have been found to play a role in other developmental processes such as identity formation (Juang, Nguyen, & Lin, 2006). Future studies with bilingual groups from varying social contexts are needed to further examine the timing of shifts to L2 dominance and its effects on children’s overall language system.

In contrast to early and rapid shifts to the L2 in the expressive modality, L1 and L2 growth rates were more consistent in the receptive modality. As shown in Figure 1, standard error for L1 and L2 trajectories of Receptive Vocabulary were overlapping, and rates of change were relatively similar for English (10%/year) and Vietnamese (7%/year). For Picture Word Verification (PWV), a measure of receptive lexical processing, there was no shift to L2 dominance in RT. (PWV accuracy was at ceiling levels, and therefore RT was the main variable for this task). Participants were equally fast in confirming or rejecting picture-word correspondences in the two languages. Although the present study did not find shifts in language dominance for this task, future shifts to the L2 cannot be ruled out. For example, Kohnert and Bates (2002) found equal performance in the L1 and L2 on a similar picture word verification task for younger age groups (< 10 years old) but found better L2 performance in the older age groups (11+ years old). Overall, later shifts in the receptive modality, particularly in receptive lexical processing, may highlight resilient aspects of the L1 lexical system in the face of increasing L2 input and shifts in relative language dominance.

Finally, children in the present study can be considered a special case because they received educational instruction in both the L1 and L2. For Spanish L1 speakers, Cobo-Lewis and colleagues (2002a, b) found that educational programming with L1 and L2 instruction positively impacted L1 outcomes and had no effect on L2 outcomes as compared to English (L2) only programs (for meta-analysis, see Rolstad et al, 2005). Unfortunately, dual-language educational programs are the exception rather than the norm in the US. Children who do not receive L1 support in the schools are at risk for L1 loss (e.g., Jia & Aaronson, 2003). Regardless of whether there is support for the L1 at the school level, the minority L1 continues to play an important role in a child’s development. Children who have high proficiency in English as well as their home language have been shown to have higher self-esteem, closer family ties, and greater academic success than their same-ethnic peers who speak solely English (Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001; Zhou & Bankston, 1994). The question of how much support is needed to promote continued L1 development particularly when school programs are unavailable is of practical and theoretical importance. Future studies are needed to examine the efficacy of other forms of systematic support for the L1 such as the role of community-based classes (Zhou & Kim, 2006).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (F31HD055113) with additional funding from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation New Century Scholars Doctoral Fellowship, University of Minnesota College of Liberal Arts Student Dissertation Research Activity Award, and Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences Bryng Bryngelson Research Award. Portions of this study were presented at the 2010 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention in Chicago, Illinois, and the 2012 Society for Research in Child Development Themed Meeting: Positive Development of Minority Children in Tampa, Florida. We thank Moin Syed, Edward Carney, and Jeffrey Long for statistical and technical support, Hai Anh Nguyen for her role as school and community liaison, the participants recruited from Hillcrest Foreign Language Academy, and Kerry Ebert for her input on previous versions of this manuscript. We acknowledge the following individuals for assistance with data collection and management: Tien Pham, Amelia Medina, Irene Hien Duong, Kelann Lobitz, Kimson Nguyen, Xuan Tang, Ellyn Dam, Bao Dang, Ly Nguyen, Samantha Yang, Maura Arnoldy, and Renata Solum.

Contributor Information

Giang Pham, Department of Communication Disorders, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Kathryn Kohnert, Department of Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences, University of Minnesota.

References

- Baayen RH, Piepenbrock R, Gulikers L. The CELEX lexical database. 2. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D. Fitting linear mixed models in R. R News. 2005;5:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zeev S. The influence of bilingualism on cognitive strategy and cognitive development. Child Development. 1977;48:1009–1018. doi: 10.2307/1128353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Sherbenou RJ, Johnsen SK. Test of nonverbal intelligence. 3. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell R. Expressive one-word picture vocabulary test. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications; 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell R. Receptive one-word picture vocabulary test. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications; 2000b. [Google Scholar]

- Clark EV. The lexicon in acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo-Lewis AB, Pearson BZ, Eilers RE, Umbel VC. Effects of bilingualism and bilingual education on oral and written English skills: A multifactor study of standardized test outcomes. In: Oller DK, Eilers RE, editors. Language and literacy in bilingual children. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters; 2002a. pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo-Lewis AB, Pearson BZ, Eilers RE, Umbel VC. Effects of bilingualism and bilingual education on oral and written Spanish skills: A multifactor study of standardized test outcomes. In: Oller DK, Eilers RE, editors. Language and literacy in bilingual children. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters; 2002b. pp. 98–117. [Google Scholar]

- Crainiceanu CM, Ruppert D. Restricted likelihood ratio tests in nonparametric longitudinal models. Statistica Sinica. 2004;14:713–730. [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan C, Campbell TF. Nonword repetition and child language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:1136–1146. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4105.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L, Dunn L. Peabody picture vocabulary test-revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L, Padilla E, Lugo D, Dunn L. Test de vocabulario en imágenes Peabody—adaptación Hispanoamericana [Peabody picture vocabulary test—Latin American adaptation] Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Elman JL. In: Language as a dynamical system. Port R, Van Gelder T, editors. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1995. pp. 195–223. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Perfors A, Marchman V. Picking up speed in understanding: Speech processing efficiency and vocabulary growth across the 2nd year. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:98–116. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. The role of phonological memory in vocabulary acquisition: A study of young children learning new names. British Journal of Psychology. 1990;81:439–454. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1990.tb02371.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Willis CS, Emslie H, Baddeley AD. Phonological memory and vocabulary development during the early school years: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:887–898. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.28.5.887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Clellen V, Simon-Cereijido G, Sweet M. Predictors of second language acquisition in Latino children with specific language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2012;21:64–77. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0090). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ET, Hall E. How cultures collide. Psychology Today. 1976;10:66–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer CS, Lawrence FR, Miccio AW. Bilingual children’s language abilities and early reading outcomes in Head Start and kindergarten. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2007;38:237–248. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2007/025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Aaronson D. A longitudinal study of Chinese children and adolescents learning English in the United States. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24:131–161. doi: 10.1017/S0142716403000079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Kohnert K, Collado J, Aquino-Garcia F. Action naming in Spanish and English by sequential bilingual children and adolescents. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2006;49:588–602. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/042). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, Nguyen H, Lin Y. The ethnic identity, other-group attitudes, and psychosocial functioning of Asian American emerging adults from two contexts. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:542–568. doi: 10.1177/0743558406291691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kail R. Development of processing speed in childhood and adolescence. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 1991;23:151–185. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2407(08)60025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan PF, Kohnert K. A growth curve analysis of novel word learning by sequential bilingual preschool children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2012;15:452–469. doi: 10.1017/S1366728911000356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K. Picture naming in early sequential bilinguals: A 1-year follow-up. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:759–771. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/061). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Bates E. Balancing bilinguals II: Lexical comprehension and cognitive processing in children learning Spanish and English. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:347–359. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/027). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Bates E, Hernandez AE. Balancing bilinguals: Lexical-semantic production and cognitive processing in children learning Spanish and English. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 1999;42:1400–1413. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4206.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Windsor J, Yim D. Do language-based processing tasks separate children with language impairment from typical bilinguals? Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2006;21:19–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5826.2006.00204.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD. The promise of dynamic systems approaches for an integrated account of human development. Child Development. 2003;71:36–43. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J. Longitudinal data analysis for the behavioral sciences using R. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Long J, Ryoo J. Using fractional polynomials to model non-linear trends in longitudinal data. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2010;63:177–203. doi: 10.1348/000711009X431509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Kim C, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Studying multivariate change using multilevel models and latent curve models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1997;32:215–253. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3203_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman V, Fernald A, Hurtado N. How vocabulary size in two languages relates to efficiency in spoken word recognition by young Spanish-English bilinguals. Journal of Child Language. 2010;37:817–840. doi: 10.1017/S0305000909990055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oller DK, Eilers RE. Language and literacy in bilingual children. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez CL, Carlo MS, Snow CE, McLaughlin B. Depth and breadth of vocabulary in two languages: Which vocabulary skills transfer? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:719–728. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.94.4.719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BZ. Social factors in childhood bilingualism in the United States. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2007;28:399–410. doi: 10.1017/S014271640707021X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED. Lost in translation: Methodological considerations in cross-cultural research. Child Development. 2007;78:1255–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED, Bedore LM, Zlatic-Giunta R. Category-generation performance of bilingual children: The influence of condition, category, and language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:938–947. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/076). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham G, Kohnert K. Sentence interpretation by typically developing Vietnamese–English bilingual children. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2010;31:507–529. doi: 10.1017/S0142716410000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham G, Kohnert K, Carney E. Corpora of Vietnamese Texts: Lexical effects of intended audience and publication place. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:154–163. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Romero I, Nava M, Huang D. The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:135–153. doi: 10.1023/A:1010389607319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo MA. Identifiers of predominantly Spanish-speaking children with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:1398–1411. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4106.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo MA, Morgan GP, Thompson MS. The efficacy of a vocabulary intervention for dual-language learners with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012 doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0173). Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas R, Iglesias A. The language growth of Spanish-speaking English language learners. Child Development. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01871.x. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolstad K, Mahoney K, Glass GV. The big picture: A meta-analysis of program effectiveness research on English language learners. Educational Policy. 2005;19:572–594. doi: 10.1177/0895904805278067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheipl F, Greven S, Küchenhoff H. Size and power of tests for a zero random effect variance or polynomial regression in additive and linear mixed models. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2008;52:3283–3299. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2007.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB, Samuelson LK. Different is good: Connectionism and dynamic systems theory are complementary emergentist approaches to development. Developmental Science. 2003;6:434–439. [Google Scholar]

- Szekely A, Jacobsen T, D’Amico S, Devescovi A, Andonova E, Herron D, Wicha N. A new on-line resource for psycholinguistic studies. Journal of Memory and Language. 2004;51:247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G. Cross-linguistic analysis of Vietnamese and English with implications for Vietnamese language acquisition and maintenance in the United States. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement. 2007;2:1–33. Retrieved from http://jsaaea.coehd.utsa.edu/index.php/JSAAEA/article/viewArticle/13. [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E, Ulrich BD, Wolff PH. Hidden skills: A dynamic systems analysis of treadmill stepping during the first year. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1991;56:1–103. doi: 10.2307/1166099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelli P, Páez MM. Narrative and vocabulary development of bilingual children from kindergarten to first grade: Developmental changes and associations among English and Spanish skills. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2007;38:225–236. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2007/024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbel VM, Pearson BZ, Fernández MC, Oller DK. Measuring bilingual children’s receptive vocabularies. Child Development. 1992;63:1012–1020. doi: 10.2307/1131250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USCensus Bureau. US Census data. 2010 Retrieved from www.census.gov.

- van Geert P. A dynamic systems model of basic developmental mechanisms: Piaget, Vygotsky and beyond. Psychological Review. 1998;105:634–677. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.105.4.634-677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71:42–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW. Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery-Revised: English Form. Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, Sandoval AFM. Batería Woodcock-Muñoz: Pruebas de Aprovechamiento Revisada. Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing Company; 1996. [Woodcock-Munoz Battery: Achievement Tests Revised] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Bankston CL. Social capital and the adaptation of the second generation: The case of Vietnamese youth in New Orleans. International Migration Review. 1994;28:821–845. doi: 10.2307/2547159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Kim SS. Community forces, social capital, and educational achievement: The case of supplementary education in the Chinese and Korean immigrant communities. Harvard Educational Review. 2006;76:1–29. [Google Scholar]