Abstract

Background

Men who have sex with men (MSM) who report receptive anal intercourse (RAI) are currently recommended to undergo annual screening for rectal C. trachomatis (CT) and N. gonorrhoeae (GC) infection.

Methods

Using standard culture methods, we assessed prevalence of rectal GC/CT among MSM who reported RAI in the last year (n=326) at an urban STD clinic in a midwestern US city. A subset (n=125) also underwent rectal GC/CT screening via nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). We examined associations between HIV status and prevalence of rectal GC and rectal CT using unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models.

Results

Prevalence of rectal GC, rectal CT and either rectal infection was 9%, 9% and 15% by culture and 24%, 23% and 38% by NAAT, respectively. HIV was not associated with rectal GC prevalence in unadjusted or adjusted analyses. HIV-positive status was significantly associated with increased rectal CT prevalence in unadjusted models (odds ratio (OR): 2.18, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.04, 4.60); this association increased after multivariable adjustment (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 1.37, 7.19).

Conclusions

MSM reporting RAI had high prevalence of rectal GC and rectal CT. HIV-positive status was significantly associated with prevalent rectal CT, but not with prevalent rectal GC.

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States (US) are disproportionately affected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). MSM accounted for half of prevalent HIV cases the US by the end of 2008 (1); of the estimated 48,100 incident HIV cases in 2009, a majority (61%) occurred in gay and bisexual men (2). The median prevalence of N. gonorrhoeae (GC) and C. trachomatis (CT) among US MSM attending STD Surveillance Network clinics in 2010 (including rectal, urethral and oropharyngeal infections with these pathogens) was 15.5% and 13.0%, respectively (3). Focusing just on rectal GC and CT, prevalence estimates in MSM as high as 38% for rectal GC (4) and 24% for rectal CT (5) have been documented. By contrast, in nationally-representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, 14-39 year-old men and women had urethral GC and CT prevalence of 0.24% and 2.2%, respectively (6).

Nearly two decades of epidemiologic data confirm a dangerous synergy between HIV and other STDs (7-8). It is plausible that rectal STDs increase risk of HIV transmission and acquisition through anal intercourse. Only one study has evaluated differences in rectal HIV shedding among MSM with rectal GC/CT compared to MSM without rectal GC/CT (9); those authors reported no differences in HIV shedding among MSM with rectal GC/CT compared to MSM without GC/CT. However, correlations exist between HIV, rectal GC and rectal CT among MSM using STD Surveillance Network data: rectal GC and CT prevalences in 2010 were 8.1% and 11.7% in HIV-uninfected MSM and 14.4% and 19.6% in HIV-infected MSM (3).

Given existing data suggesting that rectal GC and CT may differ by HIV status among MSM, we undertook a project in an urban, public STD clinic in a midwestern US city. Our study had two aims: 1) to assess the prevalence of rectal GC and rectal CT among MSM reporting receptive anal intercourse (RAI) in the last 12 months; and 2) to examine associations between HIV status and prevalence of rectal GC/CT in the same population of MSM.

Methods

Study design and setting

This retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted in a public STD clinic housed within a city health department. Per clinic protocol, any clinic attendee who reports RAI in the past year undergoes screening for rectal CT and GC testing by culture. The present analysis is an examination of all rectal CT and GC screening performed in male clinic attendees in the 14-month period from November 2010 to December 2011. No exclusion criteria were applied.

Validation study

From May through December 2011, MSM undergoing screening for rectal GC and CT via culture were also screened using nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) as part of an in-house laboratory validation study.

Diagnostic testing

Rectal GC cultures were performed in-house on Thayer-Martin media using standard culture methods. Rectal CT cultures were performed by Laboratory Corporation of America (LabCorp, Dublin, Ohio), the clinic reference lab, per standard procedures. NAAT was performed using Aptima Combo 2 Assay with Tigris (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA). All indeterminate NAAT results for rectal GC/CT were repeated. If the repeat test was conclusive, those results were reported; if it remained indeterminate, the result was reported as indeterminate. All clinic attendees are also screened for urethral GC and CT via NAAT on urine specimens; syphilis either via rapid plasma reagin (RPR) titers with reactive RPRs confirmed by fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay (FTA-ABS) or Treponema pallidum passive particle agglutination assay (TPPA) from serum, or dark field microscopy from any suspected syphilitic chancre; and HIV via OraQuick (OraSure Technologies, Inc, Bethlehem, PA) or Uni-Gold (Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland) rapid tests using plasma. Preliminary HIV-positive results are confirmed via western blot analysis by the Ohio Department of Health.

Data collection and extraction

A complete list of men undergoing rectal GC and CT testing during the study period was obtained from clinic billing records. We then extracted relevant behavioral, demographic and clinical data from electronic medical records. All patients complete a self-administered, one-page, paper Sexual Health Self-Assessment Form at each visit that captures data about previous STD diagnoses and treatment, HIV status, sexual behavior in the last year, intravenous drug use and the number and sex of partners. Relevant behavioral variables for this analysis from the Sexual Health Self-Assessment Form were also extracted.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We calculated prevalence of rectal GC and CT (primary outcomes) separately and as a combined GC/CT outcome. We computed prevalences separately for testing done via culture and during the NAAT validation study. We computed simple frequency statistics of demographic and behavioral data. Finally, we conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses with generalized estimating equations (GEE) and robust variance estimation (10) to account for repeat visits by some patients. Following adjustment for relevant confounders, we assessed the association between a) HIV status and rectal GC via culture; b) HIV and rectal CT via culture; and c) HIV and rectal GC/CT via culture (combined outcome). We began with fully-adjusted models which were reduced using manual backward-elimination procedures (11). Variables were retained in the final models if their removal from any individual model led to a change in the HIV-rectal GC/CT association of ≥10%. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

We conducted two sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our observed measures of effect. First, we restricted the analysis to include only men's first visits to the clinic within the study window; successive visits by repeat attendees were excluded to determine whether our primary findings were skewed by the presence of men who returned for multiple visits. Second, we repeated all primary analyses using rectal GC and CT results via NAAT, for the subset of participants in the NAAT validation sample.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. All study procedures were undertaken in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Results

A total of 326 men were screened for rectal CT and GC via culture during the study period. Twenty-four men (7%) returned two times within the study window and 4 men (1%) returned three times; the analysis dataset thus includes 354 study visits. During the NAAT validation study, 125 men from the larger sample were screened for rectal GC and CT using both NAAT and culture methods.

Demographic, behavioral and clinical characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of MSM undergoing rectal testing for chlamydial and gonococcal infection, via culture (n=326) or NAAT (n=125), 2010-2011.

| Characteristic | Culture | NAAT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N=326 | (%) | N=125 | (%) | |

| Race* | ||||

| Black | 121 | (37) | 47 | (38) |

| White | 185 | (57) | 69 | (55) |

| Other | 21 | (6) | 10 | (10) |

| Education | ||||

| Did not finish high school | 31 | (10) | 12 | (10) |

| High school or GED | 57 | (17) | 14 | (11) |

| Some college | 134 | (41) | 58 | (46) |

| College graduate | 88 | (27) | 35 | (28) |

| Missing | 16 | (5) | 6 | (5) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 299 | (92) | 115 | (92) |

| Married | 5 | (2) | 1 | (1) |

| Civil union | 2 | (1) | 2 | (2) |

| Separated/divorced | 14 | (4) | 6 | (5) |

| Widowed | 2 | (1) | 1 | (1) |

| Missing | 4 | (1) | 0 | (0) |

| In the last year, have you had … | ||||

| Sex with women? | ||||

| Yes | 32 | (10) | 13 | (10) |

| No | 281 | (86) | 107 | (86) |

| Missing | 13 | (4) | 5 | (4) |

| Sex without a condom? | ||||

| Yes | 286 | (88) | 112 | (90) |

| No | 34 | (10) | 11 | (9) |

| Missing | 6 | (2) | 2 | (2) |

| Sex with known HIV-positive partners? | ||||

| Yes | 32 | (10) | 11 | (9) |

| No | 220 | (67) | 81 | (65) |

| Missing | 74 | (23) | 33 | (26) |

| Sex with partners of unknown HIV status? | ||||

| Yes | 88 | (27) | 31 | (25) |

| No | 125 | (38) | 49 | (39) |

| Missing | 113 | (35) | 45 | (36) |

| Sex with anonymous partners? | ||||

| Yes | 85 | (26) | 39 | (31) |

| No | 125 | (38) | 42 | (34) |

| Missing | 116 | (36) | 44 | (35) |

| Sex while using drugs or alcohol? | ||||

| Yes | 107 | (33) | 39 | (31) |

| No | 108 | (33) | 40 | (32) |

| Missing | 111 | (34) | 46 | (37) |

| Sex in exchange for money or drugs? | ||||

| Yes | 5 | (2) | 4 | (3) |

| No | 193 | (59) | 71 | (57) |

| Missing | 128 | (39) | 50 | (40) |

Race categories sum to more than the total sample size because some patients selected more than one race.

Participants were predominantly black (37%) or white (57%), with a median age of 27 years. Most men (86%) had at least a high school education. Almost all (92%) were unmarried. Ten percent reported sex with women in the last year, and 88% reported ever having sex without condoms in the last year. One in ten men reported sex in the last year with a partner known to be HIV-positive. More than a quarter (27%) reported sex in the last year with a partner of unknown HIV status and a similar proportion reported sex with an anonymous partner. A third of men reported sex in the last year while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Characteristics and reported behaviors of men in the subset undergoing rectal GC/CT screening via NAAT were not meaningfully different from the full sample (Table 1).

STD and HIV prevalence

By culture methods, the prevalence of rectal GC, CT and either infection in the full study sample was 9%, 9% and 15%, respectively. In the sample undergoing screening via NAAT, the prevalence of rectal GC, CT and either infection was 24%, 23% and 38%, respectively. Among individuals tested by both culture and NAAT, no one had a positive culture and a negative NAAT result.

In the overall sample, 7% of men had urethral GC, 5% had urethral CT, and 12% had either urethral infection. Twenty-five of 32 (78%) men who had rectal GC via culture tested negative for urethral GC, and 19 of 30 (63%) men who had rectal GC via NAAT tested negative for urethral GC. Thirty of 31 (97%) men who had rectal CT via culture tested negative for urethral CT, and 28 of 29 (97%) men who had rectal CT via NAAT tested negative for urethral CT.

Almost a quarter (24%) of men in the full cohort had tested positive for HIV prior to their clinic visit; another 7% tested newly HIV-positive on the day of their visit. Thus total HIV prevalence was 31%. Syphilis prevalence was 17%. Of syphilis-positive men, 5% had primary syphilis, 53% had secondary syphilis, 13% had early latent syphilis, 13% had late latent syphilis, and 15% had latent syphilis of unknown duration.

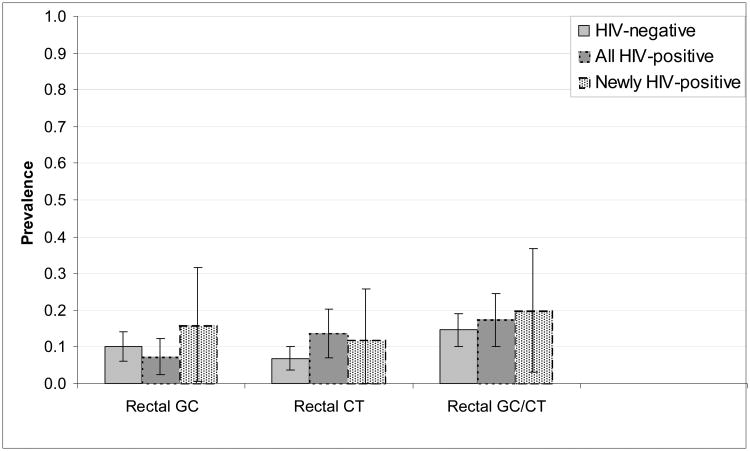

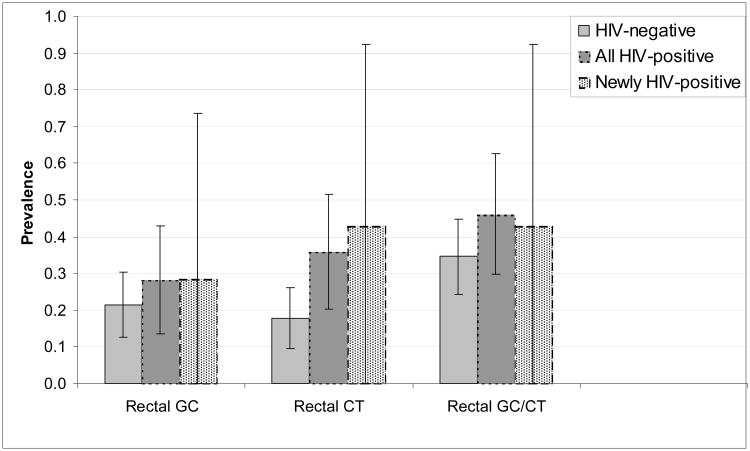

Rectal STD prevalence differed by HIV status (Figures 1a and 1b). With one exception (rectal GC detected by culture), the prevalence of rectal infections was lower among HIV-negative men than among HIV-positive men. We observed no significant differences in rectal GC or CT between men newly diagnosed with HIV and those diagnosed with HIV before the current visit. Similar patterns were seen in the subset undergoing NAAT, with wider confidence intervals given the smaller sample size.

Figure 1a.

Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of rectal GC, rectal CT and rectal GC/CT, as detected by culture, by HIV status, among MSM undergoing rectal GC and CT screening (n=354), 2010-2011.

Figure 1b.

Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of rectal GC, rectal CT and rectal GC/CT, as detected by NAAT, by HIV status, among MSM undergoing rectal GC and CT screening (n=125), 2010-2011.

Symptoms of rectal infection

The majority of patients undergoing testing (85%) reported no symptoms (Table 2). Sixty-nine percent of MSM who tested positive for rectal GC (via culture) and 58% of men who tested positive for rectal CT (via culture) reported no symptoms. Similarly, in 88% of men overall the clinician observed no signs of infection, including 58% of men with rectal CT and 78% of men with rectal GC. The most common clinician-observed sign of infection was proctitis, seen in 23% of men with rectal CT and 13% of men with rectal GC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant-reported and clinician-observed symptoms of rectal GC or CT among MSM undergoing rectal GC/CT testing via culture (n=354), 2010-2011.

| Total n=354 (%)* | Rectal CT n=31 (%)* | Rectal GC n=32 (%)* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant-reported | |||

|

| |||

| No symptoms | 300 (85) | 18 (58) | 22 (69) |

| Rectal pain | 14 (4) | 3 (10) | 3 (9) |

| Pain with defecation | 12 (3) | 5 (16) | 4 (13) |

| Rectal discharge | 50 (14) | 14 (45) | 8 (25) |

|

| |||

| Clinician-observed | |||

|

| |||

| No signs | 313 (88) | 18 (58) | 25 (78) |

| Proctitis | 14 (4) | 7 (23) | 4 (13) |

| Anal fissures | 8 (2) | 3 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Rectal tenderness | 9 (3) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Rectal discharge | 11 (3) | 5 (16) | 3 (9) |

Percentages add to >100% because many patients and clinicians reported more than one symptom per patient visit

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between HIV and rectal GC/CT via culture

We assessed age, race, sex without a condom in the last year, syphilis status at the present visit, and the number of sex partners in the last year as potential confounders of the associations between HIV and rectal GC, rectal CT and rectal GC/CT. According to our a priori criteria for confounding, all final multivariable models adjusted for age, race, and any sex without a condom in the last year.

HIV status (positive vs. negative, without stratification by timing of HIV diagnosis) was not associated with rectal GC prevalence in unadjusted or adjusted analyses (Table 3). However, HIV-positive status was associated with increased prevalence of rectal CT in unadjusted analyses (OR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.04, 4.60); after adjustment, this significant association was strengthened (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 1.37, 7.19) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between HIV and rectal GC/CT, among MSM undergoing rectal GC/CT testing via culture (n=354), 2010-2011.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR† | 95% CI† | OR | 95% CI | |

| Rectal GC† | 0.70 | 0.30, 1.61 | 0.97 | 0.40, 2.34 |

| Rectal CT† | 2.18 | 1.04, 4.60 | 3.14 | 1.37, 7.19 |

| Rectal GC/CT | 1.24 | 0.67, 2.28 | 2.16 | 1.01, 4.64 |

adjusted for age, race, and any sex without a condom in the last year

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; CT: infection with C. trachomatis; GC: infection with N. gonorrhoeae

Sensitivity analysis 1: Restriction of the analysis sample to first visits only

When the analysis was restricted to men's first visits only (n=326), the unadjusted and adjusted associations between HIV and rectal STDs were remarkably similar to the primary findings. For example, the adjusted OR for the association between HIV and rectal CT was 3.12 (95% CI: 1.33, 7.33) in this sensitivity analysis compared to OR: 3.14 (95% CI: 1.37, 7.19) in the primary findings. All other associations in the restricted sample were also similar to the primary findings; no measure changed from statistically significant to non-significant or vice-versa (data not shown).

Sensitivity analysis 2: Unadjusted and adjusted associations between HIV and rectal GC/CT via NAAT

We also assessed the associations between HIV status and rectal GC, rectal CT and rectal GC/CT in the subset of men undergoing NAAT (Table 4). The results were very similar to those obtained using rectal GC and CT status via culture. HIV status was not significantly associated with rectal GC in unadjusted or adjusted analyses. HIV-positive status was significantly associated with increased rectal CT prevalence in unadjusted (OR: 2.58, 95% CI: 1.09, 6.09) and adjusted analyses (OR: 3.02, 95% CI: 1.18 to 7.71) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis: unadjusted and adjusted associations between HIV and rectal GC/CT, among MSM undergoing rectal GC/CT testing via NAAT (n=125), 2010-2011.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR† | 95% CI† | OR | 95% CI | |

| Rectal GC† | 1.44 | 0.61, 3.44 | 2.15 | 0.83, 5.52 |

| Rectal CT† | 2.58 | 1.09, 6.09 | 3.02 | 1.18, 7.71 |

| Rectal GC/CT | 1.63 | 0.75, 3.52 | 2.18 | 0.90, 5.25 |

adjusted for age, race, and any sex without a condom in the last year

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; CT: infection with C. trachomatis; GC: infection with N. gonorrhoeae

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of MSM reporting RAI in the last year, the prevalence of both rectal GC and rectal CT was generally higher than the prevalence of these rectal infections in other MSM populations in the US (9, 12-18). In our sample, nearly one in seven MSM in whom rectal STD screening was recommended tested positive for rectal GC or CT via culture, and more than 1 in 3 had rectal GC or CT via NAAT. A sizable proportion of our study population was HIV-positive, including several individuals newly diagnosed with HIV on the date of the clinic visit. We observed significantly increased prevalence of rectal CT among HIV-positive MSM, but the prevalence of rectal GC was not significantly different by HIV status.

Nearly two decades of epidemiologic research worldwide confirms synergy between STDs and HIV across a range of populations. Both ulcerative (e.g., herpes simplex virus (HSV) type-2, syphilis) and inflammatory STDs (e.g., GC, CT) potentiate HIV acquisition and transmission (8). Among HIV-negative individuals, the odds of HIV acquisition are increased in the presence of CT, GC, trichomoniasis and genital ulcers (e.g., (19-21). In HIV-infected individuals, detection of HIV in genital secretions is significantly increased in the presence of urethritis, cervicitis, GC, CT, vulvo-vaginal candidiasis, and genital ulcer disease (22). Appropriate treatment for STDs or STD-associated inflammation (e.g. cervicitis, urethritis) significantly reduces HIV shedding in vaginal/cervical and seminal secretions (e.g., (23-24).

Despite the documented high rates of both HIV and other STDs among MSM, and existing evidence of HIV-STD synergy in non-MSM populations, HIV-STD synergy for rectal STDs and HIV has not been well-studied. One retrospective cohort study in San Francisco reported that MSM with two prior rectal GC or CT infections had an 8-fold increased risk of HIV acquisition (25). Another study of HIV-positive MSM reported no difference in rectal HIV shedding among MSM with rectal GC/CT compared to MSM without rectal GC or CT (9), however, that study was underpowered to evaluate the confounding effects of antiretroviral therapy or other STDs (9). A large, well-designed, prospective study of the associations between rectal GC and CT, rectal inflammation and rectal HIV shedding is essential to understand the role of each of these factors in HIV transmission dynamics in MSM.

As expected, the majority of men in our sample reported no symptoms. However, among men with diagnosed infections, symptoms were reported more frequently among men with rectal CT than among men with rectal GC. This counterintuitive finding raises the possibility that some CT-positive men may have been infected with an LGV serovar, which can present with proctitis and proctocolitis (26). Unfortunately, we did not perform CT serological testing or PCR-based LGV genotyping on patients with positive CT cultures, and our validated NAAT does not distinguish between CT serovars.

We, like others (e.g. (15)), found that screening MSM who report RAI for GC and CT only using urine/urethral specimens would lead to a large proportion of positive rectal infections not being treated. Depending on which infection and which diagnostic approach, between 63% and 97% of rectal GC or CT infections in our study population would not have been diagnosed – because those individuals did not also have a concurrent urethral infection with the same pathogen – if only urine screening for GC and CT had been implemented. Current CDC guidelines recommend that all MSM who report RAI within the past year undergo annual screening for rectal GC and CT, and more frequently if high risk behavioral factors are present (27). Rectal specimens are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for GC/CT detection via NAAT, but CDC considers NAAT the optimal modality for rectal GC and CT diagnosis (27). Many large reference laboratories have performed NAAT validation studies for oral and rectal GC/CT detection, and CDC offers guidance to labs who seek to perform their own validation studies. However, considerable data suggest that guidelines for the type and frequency of rectal STD testing are not routinely followed, even among HIV-infected men (28-29). Our findings provide further confirmation that screening and treatment for these rectal infections is very much needed.

This retrospective, cross-sectional study has important limitations. First, given the simultaneous measurement of HIV and rectal STD, the temporality of the observed association between HIV and rectal CT cannot be definitively established. Second, several of the sexual behavior variables we assessed are self-reported, and may suffer from recall and social desirability biases often present with measurement of sensitive behaviors. Third, the behavioral data used in these analyses were extracted from the self-administered Sexual Health Self-Assessment Form. Patients with limited literacy may not have correctly completed that form. We have no way to assess whether patients fully comprehended the questions on that form. Fourth, some selection bias may be present in our assessed sample. For example, we do not know if all clinicians followed CDC's screening guidelines for rectal STD for all patients reporting RAI in the past year with the same fidelity. Some clinicians may have only ordered rectal STD screening for patients they perceived to be at particularly increased risk of rectal infection, despite clear recommendations that all patients reporting RAI in the last year should undergo screening. Our analysis also has important strengths. We assessed the association between HIV and rectal GC and CT using both the standard diagnostic method (culture) and the newer, recommended NAAT method. We performed sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the observed associations, and although (as expected) the prevalence of rectal infections was higher using NAAT than culture methods for diagnosis, the magnitude of the associations with HIV were similar.

In summary, rectal GC and CT are highly prevalent among MSM reporting RAI in the last year and presenting for screening at an STD clinic in a midwestern US city. Rectal GC and CT are curable, and available diagnostic methodologies (especially NAAT) are sensitive and specific for their accurate detection. Because NAAT is standard for urethral and cervical GC/CT screening, the required equipment and personnel to implement more widespread screening for rectal GC/CT already exist. However, the lack of FDA approval of GC/CT screening via NAAT for extragenital sites is likely a barrier to more widespread availability of this superior screening modality. Assisting STD clinics in provision of rectal NAAT screening is thus an important public health priority. MSM in the US have critical unmet sexual health needs, reflected in their disproportionate and exceedingly high HIV and STD rates. Future interventions focused on better rectal STD screening and treatment in MSM may significantly impact HIV transmission dynamics in this most-affected group.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science (OSU CCTS). The OSU CCTS is supported by the National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1RR025755, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 8UL1TR000090-05. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Dr. Mysheika Williams Roberts for her support of this project.

References

- 1.HIV surveillance--United States, 1981-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Jun 3;60(21):689–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2010. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2011; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manavi K, Zafar F, Shahid H. Oropharyngeal gonorrhoea: rate of co-infection with sexually transmitted infection, antibiotic susceptibility and treatment outcome. Int J STD AIDS. 2010 Feb;21(2):138–40. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMillan A, Manavi K, Young H. Concurrent gonococcal and chlamydial infections among men attending a sexually transmitted diseases clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2005 May;16(5):357–61. doi: 10.1258/0956462053888925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datta SD, Sternberg M, Johnson RE, Berman S, Papp JR, McQuillan G, et al. Gonorrhea and Chlamydia in the United States among Persons 14 to 39 Years of Age, 1999 to 2002. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007 Jul 17;147(2):89–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999 Feb;75(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992 Mar-Apr;19(2):61–77. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley CF, Haaland RE, Patel P, Evans-Strickfaden T, Farshy C, Hanson D, et al. HIV-1 RNA rectal shedding is reduced in men with low plasma HIV-1 RNA viral loads and is not enhanced by sexually transmitted bacterial infections of the rectum. J Infect Dis. 2011 Sep 1;204(5):761–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988 Dec;44(4):1049–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvin S. Statistical Analysis of Epidemological Data. 3rd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, Markowitz L, Papp JR, Palella FJ, Jr, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis rectal infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2010 May;48(5):1827–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02398-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker J, Plankey M, Josayma Y, Elion R, Chiliade P, Shahkolahi A, et al. The prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrheae and Chlamydia trachomatis among asymptomatic men who have sex with men in a prospective cohort in Washington, D.C. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009 Aug;23(8):585–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis TW, Goldstone SE. Sexually transmitted infections as a cause of proctitis in men who have sex with men. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Mar;52(3):507–12. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819ad537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, Liska S, Gibson S, Hubbard G, et al. Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Jul 1;41(1):67–74. doi: 10.1086/430704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer KH, Bush T, Henry K, Overton ET, Hammer J, Richardson J, et al. Ongoing sexually transmitted disease acquisition and risk-taking behavior among US HIV-infected patients in primary care: implications for prevention interventions. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 Jan;39(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823b1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimiaga MJ, Helms DJ, Reisner SL, Grasso C, Bertrand T, Mosure DJ, et al. Gonococcal, chlamydia, and syphilis infection positivity among MSM attending a large primary care clinic, Boston, 2003 to 2004. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Aug;36(8):507–11. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a2ad98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moncada J, Schachter J, Liska S, Shayevich C, Klausner JD. Evaluation of self-collected glans and rectal swabs from men who have sex with men for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by use of nucleic acid amplification tests. J Clin Microbiol. 2009 Jun;47(6):1657–62. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02269-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laga M, Manoka A, Kivuvu M, Malele B, Tuliza M, Nzila N, et al. Non-Ulcerative Sexually-Transmitted Diseases as Risk-Factors for Hiv-1 Transmission in Women - Results from a Cohort Study. AIDS. 1993 Jan;7(1):95–102. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, Ndinya-Achola JO, Kreiss JK, Gakinya MN, et al. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1991 Feb;163(2):233–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rottingen JA, Cameron DW, Garnett GP. A systematic review of the epidemiologic interactions between classic sexually transmitted diseases and HIV: how much really is known? Sex Transm Dis. 2001 Oct;28(10):579–97. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200110000-00005. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson LF, Lewis DA. The Effect of Genital Tract Infections on HIV-1 Shedding in the Genital Tract: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2008 Nov;35(11):946–59. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181812d15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MS, Hoffman IF, Royce RA, Kazembe P, Dyer JR, Daly CC, et al. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet. 1997 Jun 28;349(9069):1868–73. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)02190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClelland RS, Wang CC, Mandaliya K, Overbaugh J, Reiner MT, Panteleeff DD, et al. Treatment of cervicitis is associated with decreased cervical shedding of HIV-1. AIDS. 2001 Jan 5;15(1):105–10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101050-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Rectal Gonorrhea and Chlamydia Reinfection Is Associated With Increased Risk of HIV Seroconversion. Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010 Apr 1;53(4):537–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson D, Goldmeier D. Lymphogranuloma venereum: an emerging cause of proctitis in men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2007 Jan;18(1):11–4. doi: 10.1258/095646207779949916. quiz 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(RR-12) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berry SA, Ghanem KG, Page KR, Thio CL, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Gonorrhoea and chlamydia testing rates of HIV-infected men: low despite guidelines. Sex Transm Infect. 2010 Nov;86(6):481–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.041541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoover KW, Butler M, Workowski K, Carpio F, Follansbee S, Gratzer B, et al. STD Screening of HIV-Infected MSM in HIV Clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2010 Dec;37(12):771–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e50058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]