Abstract

In this study we present a novel method for studying cellular traction force generation and mechanotransduction in the context of cardiac development. Rat hearts from three distinct stage of development (fetal, neonatal and adult) were isolated, decellularized and characterized via mechanical testing and protein compositional analysis. Stiffness increased ~2 fold between fetal and neonatal time points but not between neonatal and adult. Composition of structural extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins was significantly different between all three developmental ages. ECM that was solubilized via pepsin digestion was cross-linked into polyacrylamide gels of varying stiffness and traction force microscopy was used to assess the ability of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to generate traction stress against the substrates. The response to increasing stiffness was significantly different depending on the developmental age of the ECM. An investigation into early cardiac differentiation of MSCs demonstrated a dependence of the level of expression of early cardiac transcription factors on the composition of the complex ECM. In summary, this study found that complex ECM composition plays an important role in modulating a cell’s ability to generate traction stress against a substrate, which is a significant component of mechanotransductive signaling.

Keywords: extracellular matrix, mesenchymal stem cells, traction stress, mechanotransduction

Introduction

In the past decade or more, a significant amount of research effort has been devoted to studying the role of substrates properties on cell fate and function. Substrate stiffness has been shown to influence proliferation [1], migration [1,2] and differentiation [3], while the protein composition of the substrate can modulate differentiation [4], as well as the response to growth factors [5] and mechanical stretch [6]. The effects of substrate properties on cell fate and function are particularly important in the heart where it is known that both organ stiffness and extracellular matrix composition change significantly during development. In particular, cardiac stiffness increases 2–3 fold from fetal to adult life stages [7] while studies into the protein content of the ECM during cardiac development observed significant alterations in the amount of fibronectin [8] and collagens [9] during fetal/neonatal development. However, these studies were carried out over short windows of time during early development, even though there are significant changes to the postnatal cardiac ECM composition. Moreover, none of these studies correlated alterations to the protein content or mechanical stiffness of the cardiac ECM to changes in cell fate and function.

The ECM in vivo is a dynamic, complex organization of proteins, polysaccharides, and glycoproteins that are expressed in varying ratios dependent upon tissue location, form, function and age. Given recent evidence that cells respond differently to external stimuli when cultured on substrates of different composition [5,6], it is likely that studies using singular proteins as binding sites for mechanotransduction experiments are not capturing the full response resulting from the complex environment in vivo. The development of decellularization techniques [10] has led to the use of whole organ ECM as a scaffold for regenerative medicine applications in the heart. Specifically, adult ventricular ECM has been demonstrated to enhance the cardiomyogenic potential of ckit+ cardiac progenitor cells [11], increase the differentiation of embryonic stem cells [12] and result in increased ventricular function when injected into the infarcted heart without cells [13]. While these results with adult organ ECM were significant, it is likely that ECM derived from earlier stages in development would hold more cues for stem/progenitor cell differentiation and cardiomyocyte development. In addition, there has been no study to date that has systematically investigated the combined effects of complex ECM composition and stiffness on cellular traction stress. The goal of this work was to advance the concept of whole-organ ECM as a binding milieu in studies of cellular mechanotransduction.

Materials and Methods

Heart Isolation, decellularization and solubilization

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tufts University and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Hearts were isolated from Sprague Dawley rats at fetal (E18-19), neonatal (P2-3) and Adult (2–3 Months) time points and decellularized. For the adult life point, retrograde perfusion of the aorta was performed [10]. Fetal and neonatal hearts were soaked in 1% SDS solution, as diffusion and convection were sufficient for removal of the cellular material due to their smaller size. Solubilization of the ECM was achieved via pepsin digestion as described previously [14].

Characterization of Rat Heart Extracellular Matrix

To assess mechanical properties, samples were immersed in a PBS bath at room temperature and uniaxially stretched in the circumferential direction of the heart using a custom-built mechanical testing setup [15]. Portions of the left ventricular free wall were used for neonatal and adult hearts; whole heart measurements were performed on fetal tissue due to their small size (n=4 per group). The thickness and width of the tissue were measured in the unstrained state via an optical measurement system in order to calculate engineering stress and strain. The elastic modulus was taken as the slope of the linear portion of the stress-strain curve (~60–70% strain).

To analyze composition, samples were frozen at −20°C, lyophilized, and digested at a concentration of 5 mg/ml in a solution containing 5M urea, 2M thiourea, 50mM DTT, and 0.1% SDS in PBS [16]. Afterward, samples were sonicated on ice (Branson Digital Sonifier, 20 sec pulses, 30% amplitude), protein was precipitated with acetone and samples were analyzed via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Mass Spectrometry Core Facility. Common ECM structural proteins were identified and compared between developmental ages by normalizing the spectral count for each protein by the total number of spectra for all ECM proteins (n=3 per group).

MSC Culture

Rat MSCs (Cell Applications Inc., San Diego, CA) were passaged in culture using the provided protocols. For all experiments, MSC were cultured with maintenance media (20% FBS, 1% pen-strep, 2% L-glutamine in alpha-MEM) which was changed every 2–3 days. For traction force microscopy, cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells per gel to ensure that the calculated forces were attributable to a single cell. For differentiation experiments cells were seeded at 30,000 cells per gel. All experiments were performed with cells between passages 2–5.

Polyacrylamide gels incorporating cardiac ECM

Polyacrylamide (PA) gels were created by combining acrylamide solution (40%, Bio-Rad) with bis-acrylamide solution (2%, Bio-Rad) at varying concentrations to produce a range of biologically relevant stiffnesses (~9–50 kPa) [3,17,18]. Solubilized ECM from the different life points and N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (NHS) (both at 400 μg/ml) were incorporated into the acrylamide/bis-acrylamide mixture and 40 μl of PA-ECM solution was polymerized with the addition of 10% ammonium persulfate (w/v) between an activated and non-activated cover slip resulting in ~80 μm thick gels, similar to previous studies [3]. NHS covalently binds free amines together. In our case, a free amine on the ECM peptides would be covalently bound to a free amine on the polyacrylamide gel. After polymerization was complete, the non-activated cover slip was removed and the gels were washed in 1X PBS overnight.

Traction Force Microscopy

Traction force microscopy was carried out using the recipe above with the addition of 0.53 μm Amino Fluorescent Polystyrene Particles (Spherotech Inc. Libertyville, IL) in a 5% bead to final gel solution [17]. MSCs were cultured for 16–20 hours and then a fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX-81, Olympus America Inc., Chelmsford, MA) was used to acquire: 1) a transmitted image of each cell, 2) a fluorescent image of the beads near the gel surface and 3) a fluorescent image of the beads after lifting the cell with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA for 5–10 minutes. Image analysis was carried out with a custom written Matlab program supplied by Professor Jeffrey Jacot (Rice University) and the resulting total integrated traction forces and the cell area were recorded. Traction stress was calculated by taking the total integrated traction force over the cell area (n=7–16 cells per group).

Immunohistochemistry

We interrogated the PA-ECM gels for expression of the early cardiac transcription factors Nkx2.5 and GATA4 (SC-14033 and SC-1237, respectively, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) via a previously described immunohistochemistry protocol [19].

Western Blotting

Gels were placed in ice cold cell lysis buffer and underwent Western blot analysis as previously described [19]. Blots were probed for Nkx2.5 (SAB2101601, Sigma-Aldrich) and GATA4 (sc-25310, SantaCruz) in a 1:400 primary antibody dilution then rinsed in TBST and incubated in a 1:1000 dilution of HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents on a G:Box Chemi XR5 (Syngene, Cambridge, UK) and normalized to cellular β-actin expression (primary 1:1000 [A5316, Sigma-Aldrich] and secondary 1:5000). Band intensities were quantified with ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) (n=4 for each condition).

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between conditions in traction force and Western blot data were compared using a two way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (stiffness x composition). All other data was compared via Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was determined as p <0.05.

Results

ECM Characterization

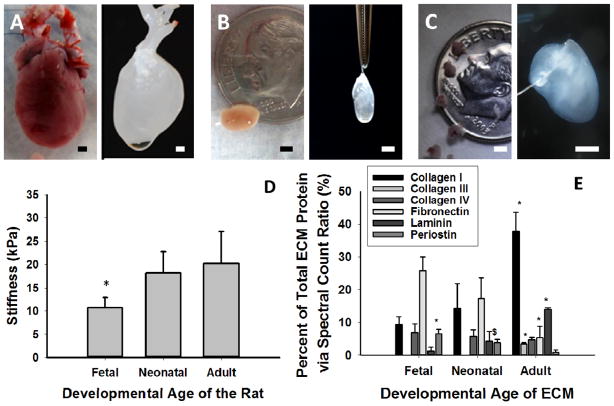

Rat hearts from the various life stages were able to be decellularized in 1% SDS solution (fetal, neonatal, adult in Figure 1B and C respectively). Mechanical testing of the hearts (Figure 1D) demonstrated that fetal hearts had a Young’s modulus of approximately 10 kPa, which was half as stiff as neonatal and adult myocardium (p<0.04). As the heart matured, there were significant increases in collagen I, collagen III and laminin (all p<0.05) (Figure 1E). Periostin and fibronectin decreased significantly with developmental age (all p<0.05), while Collagen IV remained unchanged.

Figure 1. Characterization of Cardiac Extracellular Matrix at Different Developmental Stages.

Adult (A), Neonatal (B) and Fetal (C) rat hearts were isolated and decellularized (right image). (D) Stiffness of the tissue (* denotes p<0.05 vs. all other groups). (E) LC-MS/MS analysis of cardiac ECM demonstrated significant changes to the composition of the ECM with developmental age (* denotes p< 0,05 vs. all other developmental ages for that ECM protein; $ denotes p<0.05 vs. the adult developmental ages for that ECM protein). Scale bars equal 2 mm for all images.

Cellular Traction Force is Modulated by ECM Composition

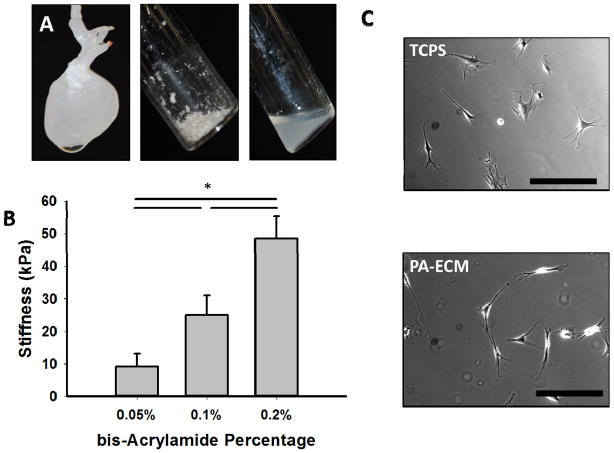

To generate PA-ECM gels, cardiac ECM was solubilized (Figure 2A) and covalently bound to PA gels using NHS ester. By combining bis-acrylamide at 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.2% with 10% acrylamide, we were able to produce PA hydrogels of 9.3 ± 3.8 kPa, 25 ± 5.9 kPa, and 48.5 ± 6.8 kPa respectively (Figure 2B). 9 kPa gels represent the stiffness of fetal hearts, 25 kPa corresponds to neonatal and healthy adult hearts and 48 kPa gels represent infarcted adult hearts. By including increasing amounts of solubilized ECM, we determined that 400 μg/ml resulted in attachment and spreading on 48 kPa gels in a manner similar to that observed on tissue culture plastic (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Creation of PA-ECM Gels.

(A) Decellularized hearts are mechanically disrupted, lyophilized (middle) and solubilized in pepsin (right). (B) PA gels can be fabricated with stiffnesses that approximate the native tissues (* denotes p<0.05). (C) Incorporation of cardiac ECM into the PA gels results in cell attachment and spreading similar to that seen on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS). Scale bars equal 100 μm.

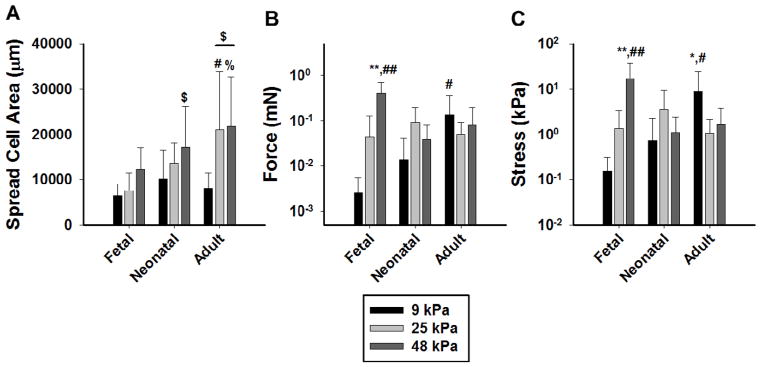

Traction force microscopy data showed that cell spread area was greatest on adult gels at 25 kPa and 48 kPa stiffness (p<0.05) (Figure 3A). In addition, spread area was significantly higher at 48 kPa as compared to 9 kPa on neonatal gels (p<0.05). In terms of traction force (Figure 3B), MSCs cultured on 9 kPa gels had the highest traction force with adult ECM as the binding sites (p<0.05), but there was no difference in force between the different stiffnesses on adult gels. Fetal gels showed a significantly increased force at 48 kPa as compared to the other stiffnesses (p<0.001) that was also significantly higher than either of the other ECM compositions at 48 kPa (p<0.001). Interestingly, the highest cellular traction stresses recorded for all conditions (Figure 3C) were generated by MSCs on fetal ECM at 48 kPa (p<0.001). MSCs cultured on adult ECM gels at 9 kPa had the second highest traction stress value (p<0.05). There was no significant difference in traction stresses on any of the substrate stiffnesses with the neonatal ECM gels.

Figure 3. Traction Force is Modulated by Complex ECM Composition.

(A) Cell spread area of MSCs on the different PA-ECM gels shows a dependence on stiffness and substrate composition ($ denotes p<0.05 vs. 9 kPa for that ECM type; # denotes p<0.05 vs. other ECM types at that stiffness; % denotes p<0.01 vs. fetal ECM at that stiffness). (B) Cellular traction force for the PA-ECM gels demonstrates differences in the response to increasing substrate stiffness depending on the ECM composition (C) Cellular traction stress for all PA-ECM gels (* denotes p <0.05 vs. all other stiffness for that ECM types; ** denotes p<0.001 vs. all other stiffnesses for that ECM type; # denotes p<0.05 vs. all other ECM types at that stiffness; ## denotes p<0.001 vs. all other ECM types at that stiffness). In all three plots there was a significant interaction between stiffness and ECM composition as determined by two-way ANOVA (p<0.05).

Expression of early cardiac markers on PA-ECM gels

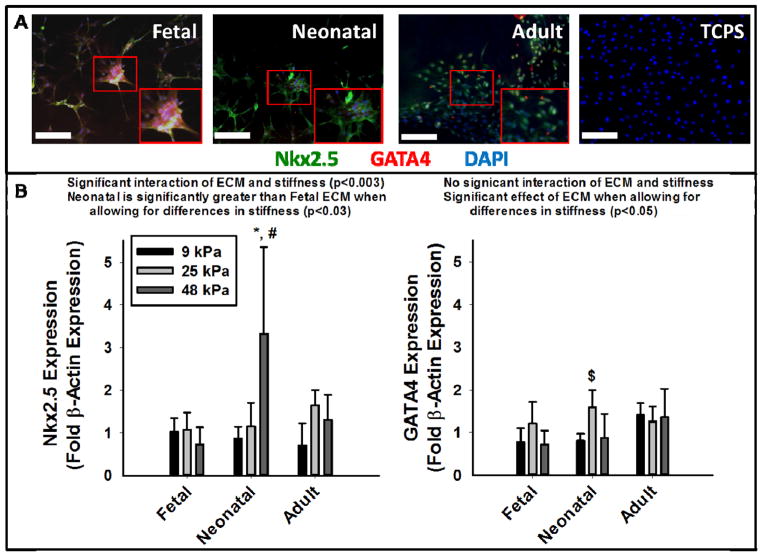

After 1 week in culture cells appear attached and well spread, and all express some level of Nkx2.5 and GATA4 when cultured on PA-ECM gels but not on TCPS (Figure 4A. An increase in substrate stiffness negatively influenced Nkx2.5 expression in the presence of fetal ECM, but promoted the expression in the presence of neonatal and adult ECM. In particular, Nkx2.5 expression was most significant on the stiffest gels (48 kPa) incorporated with neonatal ECM (p<0.001). Alternatively, stiffness only appeared to influence GATA4 expression in the presence of fetal or neonatal ECM, while adult ECM generated similar expression levels of GATA4 for all three stiffnesses. 25 kPa gels promoted GATA4 expression with the most significant expression observed in the presence of neonatal ECM (p<0.05 compared to 9 kPa neonatal gels).

Figure 4. Early Cardiac Differentiation of MSCs on PA-ECM Gels.

(A) Representative histological images for each of the PA-ECM gels at 25 kPa and cells on TCPS (Nkx2.5 = green, GATA 4 = red, DAPI nuclei = blue). Note that all ECM compositions resulted in some degree of expression of both cardiac markers while TCPS did not. (B) Quantification of expression of Nkx2.5 (left) and GATA4 (right) for each of the PA-ECM gels from Western blot analysis (presented as fold β-actin expression). Two-way ANOVA determined a significant interaction between composition and stiffness on Nkx 2.5 expression (p<0.003) and that expression of Nkx2.5 is significantly greater on neonatal gels than it is on fetal gels (p<0.03). In addition, there was a significant effect of ECM composition on GATA 4 expression when allowing for the effects of differences in stiffness (p<0.05). * denotes p<0.001 compared to other stiffnesses within ECM type, # denotes p< 0.001 when compared to other ECM types within stiffness, and $ denotes p<0.05 when compared to 9 kPa neonatal gels. Scale bars equal 100 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we have presented a novel method for investigating cellular traction stress and mechanotransduction in the context of the complex composition of the ECM of the developing heart. Our characterization of the ECM from different developmental stages (Figure 1) shows distinct changes in both stiffness and composition which mirror the results of previous studies (mechanical properties [7] and composition [8,9]). To our knowledge there has been only one other study using a decellularized organ scaffold from a younger developmental age, which found that fetal and juvenile kidney ECM resulted in the best cell repopulation and the formation of tubular structures within the decellularized tissue section [20]. However, this study did not control for stiffness in the culture, which could have a significant impact on their findings based on the data presented here. Our study is the first to look at early developmental age ECM in the heart and also the first to study how complex composition and substrate stiffness interact to alter the ability of cells to generate traction stress.

It is important to note that the forces [17] and cell areas [21] we report here are similar to values previously reported in the literature (Figure 3). Of particular significance is the finding that increasing stiffness from 9 to 48 kPa resulted in a significant decrease in the stress generated by cells on adult ECM gels but a significant increase in stress generated by MSCs on the fetal ECM gels. Cell spread area generally increases with stiffness in our experiment except on the adult ECM composition where the spread area plateaus at the higher two substrates stiffnesses (Figure 3C). This result agrees with a previous study carried out on a singular ECM protein that demonstrated a plateau in the cell spread area at higher substrate stiffnesses [18]. In terms of traction force, a few studies have reported that cell traction force increases with increasing substrate stiffness before reaching a plateau in the range of 20–50 kPa [18]. This appears to be the case on fetal ECM but not on either the neonatal or adult ECM composition. Given the significant differences in composition of ECM at these stages, it is possible that related alterations in integrin expression/ binding of the cells to the substrate could shift this plateau. Another potential cause for the difference between the conditions could be related to differences in binding ligand density. Engler et al. has previously shown an increase in traction force and cell spread area as a function of increasing collagen density on gels [22]. Our data also demonstrates a potential dependence between collagen concentration and cell-spread area, particularly at higher substrate stiffnesses (Figure 1E, Figure 2A). However, traction force/stress generation does not appear to be modulated by collagen composition.

PA-ECM gels of different stiffnesses allow for adherence and spreading of MSCs and in all cases we see expression of early cardiac transcription factors Nkx2.5 and GATA4, while culture on standard tissue culture plates devoid of any ECM proteins demonstrated no expression (Figure 4A for histology, Western data not shown). This is particularly significant since the cells were cultured in standard growth medium, which did not contain soluble factors typically used to differentiate the cells towards a cardiac lineage such as 5-azacytidine [23]. Quantifying this data shows that there was a significant effect of ECM composition on GATA 4 expression when allowing for the effects of differences in stiffness (p<0.05). Moreover, gels with neonatal ECM resulted in significantly greater expression of Nkx2.5 when accounting for the effects of differences in stiffness (p< 0.03). The finding that complex ECM can enhance the differentiation of stem cells is not a new one. Recent work by Zhang et al found that culturing a number of different iPSC lines on Matrigel resulted in significantly enhanced cardiac differentiation from standard differentiation protocols [4]. Cardiac specific ECM has been shown to enhance cardiac differentiation in both hESC [12] and ckit+ cardiac progenitor cells [11]. In all of these cases the cardiac ECM was derived from an adult organ. In our study, neonatal and adult ECM seem to be the best at promoting a combination of both Nkx2.5 and GATA4 expression particularly at higher stiffnesses (25 kPa and 48 kPa). The neonatal time point in our study corresponds with the period of time when cardiomyocytes undergo postnatal terminal differentiation and lose their ability to proliferate [24]. It is believed that the increase in stress in the heart following birth alters the matrix composition of the heart and we believe this newly deposited matrix is positively influencing the stem cells’ potential for cardiac differentiation. While other studies have demonstrated that adult cardiac ECM promotes the potential of stem cells for cardiac differentiation [11,12], our results suggests that the neonatal matrix could prove more effective. While previous studies have indicated that stiffness alone can direct differentiation lineage [3], our data demonstrate that stiffness is not the only contributing factor. Differentiation seems to occur reasonably well at all stiffnesses but with different responses to increasing stiffness depending on the composition of the ECM (Figure 4B). Analysis of the data via two-way ANOVA indicated that there was a significant effect of composition on Nkx2.5 and GATA 4 expression. These findings highlight the importance of the composition of the ECM in studies looking at the effects of cellular mechanotransduction on cardiac differentiation. Previous work by Engler et al demonstrated the greatest degree of skeletal muscle differentiation of MSCs on substrates coated with fibronectin with stiffnesses between 9 and 17 kPa [3]. Our data demonstrate that in the presence of complex ECM, MSCs generally have lower cardiac differentiation potential on lower stiffnesses (9 kPa) with increased differentiation at higher stiffnesses (25 kPa and 48 kPa). As a follow up, we investigated whether there were any correlations between the early cardiac differentiation potential and the measures derived from TFM (see Supplementary Figure 1). The strongest correlations were between GATA 4 expression and cellular traction stress or force (r2 = 0.52 and 0.69, respectively). In general there was low correlation between Nkx2.5 expression and traction force measures, although lower traction stress and force tended to result in higher expression. These correlations confirm previous findings that differentiation induced via substrate stiffness is directly related to the cells ability to generate tension against the substrate [3].

It is important to note that our study has some limitations associated with it. There are likely small changes in the composition of the cardiac ECM from batch-to-batch and this possibly contributed to the variability in our data. One potential solution to this issue is to make a synthetic mimic of the ECM composition by combining recombinant proteins in the exact ratios determined from the LC-MS/MS analysis to ensure consistency of the binding sites and this will be explored in future studies. MSCs have been previously demonstrated to express early cardiac transcription factors and the expression of these factors has been implicated in the potential beneficial effects of MSCs following implantation into the injured heart; however, the ability of MSCs to differentiate into contractile myocytes is controversial. Further explorations with this system include the application of other cell types with greater functional cardiomyogenic potential.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cardiac ECM composition and stiffness change significantly during development

Cardiac ECM can be incorporated into polyacrylamide gels of varying stiffnesses

Traction stress of MSCs increases with increasing stiffness on fetal ECM gel

MSCs on adult ECM gels generate lower traction stress on higher stiffness gels

Cardiac transcription factor expression is optimized on neonatal ECM gels

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Professor Jeffrey Jacot of Rice University for supplying the Matlab code used for the traction force analysis and Professor John Asara and the Mass Spectrometry Core Laboratory at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for proteomics analysis of the ECM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ghosh K, Pan Z, Guan E, Ge S, Liu Y, Nakamura T, Ren XD, Rafailovich M, Clark RA. Cell adaptation to a physiologically relevant ECM mimic with different viscoelastic properties. Biomaterials. 2007;28:671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent LG, Choi YS, Alonso-Latorre B, Del Alamo JC, Engler AJ. Mesenchymal stem cell durotaxis depends on substrate stiffness gradient strength. Biotechnol J. 2013;8:472–484. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Klos M, Wilson GF, Herman AM, Lian X, Raval KK, Barron MR, Hou L, Soerens AG, Yu J, Palecek SP, Lyons GE, Thomson JA, Herron TJ, Jalife J, Kamp TJ. Extracellular matrix promotes highly efficient cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells: the matrix sandwich method. Circ Res. 2012;111:1125–1136. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong TT, Shaw RM, Srivastava D. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacKenna DA, Dolfi F, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation by mechanical stretch is integrin-dependent and matrix-specific in rat cardiac fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:301–310. doi: 10.1172/JCI1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacot JG, Martin JC, Hunt DL. Mechanobiology of cardiomyocyte development. J Biomech. 2010;43:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farhadian F, Contard F, Corbier A, Barrieux A, Rappaport L, Samuel JL. Fibronectin expression during physiological and pathological cardiac growth. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:981–990. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borg TK, Gay RE, Johnson LD. Changes in the distribution of fibronectin and collagen during development of the neonatal rat heart. Coll Relat Res. 1982;2:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(82)80015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, Taylor DA. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature’s platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213–221. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French KM, Boopathy AV, DeQuach JA, Chingozha L, Lu H, Christman KL, Davis ME. A naturally derived cardiac extracellular matrix enhances cardiac progenitor cell behavior in vitro. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:4357–4364. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeQuach JA, Mezzano V, Miglani A, Lange S, Keller GM, Sheikh F, Christman KL. Simple and high yielding method for preparing tissue specific extracellular matrix coatings for cell culture. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seif-Naraghi SB, Singelyn JM, Salvatore MA, Osborn KG, Wang JJ, Sampat U, Kwan OL, Strachan GM, Wong J, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Braden RL, Bartels K, DeQuach JA, Preul M, Kinsey AM, DeMaria AN, Dib N, Christman KL. Safety and efficacy of an injectable extracellular matrix hydrogel for treating myocardial infarction. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:173ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singelyn JM, DeQuach JA, Seif-Naraghi SB, Littlefield RB, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Christman KL. Naturally derived myocardial matrix as an injectable scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5409–5416. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black LD, Brewer KK, Morris SM, Schreiber BM, Toselli P, Nugent MA, Suki B, Stone PJ. Effects of elastase on the mechanical and failure properties of engineered elastin-rich matrices. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1434–1441. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00921.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngoka LC. Sample prep for proteomics of breast cancer: proteomics and gene ontology reveal dramatic differences in protein solubilization preferences of radioimmunoprecipitation assay and urea lysis buffers. Proteome Sci. 2008;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dembo M, Wang YL. Stresses at the cell-to-substrate interface during locomotion of fibroblasts. Biophys J. 1999;76:2307–2316. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77386-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tee SY, Fu J, Chen CS, Janmey PA. Cell shape and substrate rigidity both regulate cell stiffness. Biophys J. 2011;100:L25–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black LD, 3rd, Meyers JD, Weinbaum JS, Shvelidze YA, Tranquillo RT. Cell-induced alignment augments twitch force in fibrin gel-based engineered myocardium via gap junction modification. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3099–3108. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakayama KH, Batchelder CA, Lee CI, Tarantal AF. Renal tissue engineering with decellularized rhesus monkey kidneys: age-related differences. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2891–2901. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron AR, Frith JE, Cooper-White JJ. The influence of substrate creep on mesenchymal stem cell behaviour and phenotype. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5979–5993. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engler A, Bacakova L, Newman C, Hategan A, Griffin M, Discher D. Substrate compliance versus ligand density in cell on gel responses. Biophys J. 2004;86:617–628. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makino S, Fukuda K, Miyoshi S, Konishi F, Kodama H, Pan J, Sano M, Takahashi T, Hori S, Abe H, Hata J, Umezawa A, Ogawa S. Cardiomyocytes can be generated from marrow stromal cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:697–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI5298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Sadek HA. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.