Abstract

Background

Familial dilated cardiomyopathy is a genetically heterogeneous disease with >30 known genes. TTN truncating variants were recently implicated in a candidate gene study to cause 25% of familial and 18% of sporadic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) cases.

Methods and Results

We used an unbiased genome-wide approach employing both linkage analysis and variant filtering across the exome sequences of 48 individuals affected with DCM from 17 families to identify genetic cause. Linkage analysis ranked the TTN region as falling under the second highest genome-wide multipoint linkage peak, MLOD 1.59. We identified six TTN truncating variants carried by affected with DCM in 7 of 17 DCM families (LOD 2.99); 2 of these 7 families also had novel missense variants segregated with disease. Two additional novel truncating TTN variants did not segregate with DCM. Nucleotide diversity at the TTN locus, including missense variants, was comparable to five other known DCM genes. The average number of missense variants in the exome sequences from the DCM cases or the ~5,400 cases from the Exome Sequencing Project was ~23 per individual. The average number of TTN truncating variants in the Exome Sequencing Project was 0.014 per individual. We also identified a region (chr9q21.11-q22.31) with no known DCM genes with a maximum heterogeneity LOD score of 1.74.

Conclusions

These data suggest that TTN truncating variants contribute to DCM cause. However, the lack of segregation of all identified TTN truncating variants illustrates the challenge of determining variant pathogenicity even with full exome sequencing.

Keywords: genetics, human, genome-wide analysis, dilated cardiomyopathy, exome

Introduction

Whole exome sequencing technologies are rapidly enabling the identification of novel rare variants in patients with cardiomyopathy, but assigning pathogenicity remains challenging. Truncating variants in TTN were recently observed in 25% of familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) cases.1 DCM is genetically heterogeneous with rare variants in over 30 disease genes, including TTN, previously indicated to cause DCM.2, 3 Prior to the recent publication of TTN contributing to a major fraction of genetic DCM, the fraction of cases attributable to any single gene ranged from <0.5% to ~6% per disease gene.4

Discovery and incorporation into clinical tests of a single gene accounting for a large fraction of DCM cases could be helpful for presymptomatic diagnosis in at-risk family members, but the clinical translation of this finding is confounded by several factors. First, despite a significant excess of truncating variants in DCM cases, these variants also occur in ~3% of controls.1 This is not unusual in complex trait analysis, where common genetic variants occur more frequently but not exclusively in cases compared to controls, and increase disease risk or susceptibility. However, in the context of DCM, which has been categorized primarily as a rare-variant Mendelian disease with marked locus and allelic heterogeneity,5 it is essential to know which truncating variants are pathogenic. Second, with over 300 exons and >34,000 amino acids, TTN has the largest coding sequence in the genome, and the majority of the general population will have at least one rare (defined as a mean allele frequency <0.5%) missense or truncating variant at this locus. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) now allows rapid variation analysis of the TTN gene despite its size. However, it relies on an economy of scale, and for a similar cost as sequencing TTN alone, NGS can be used to sequence the entire coding sequence of the genome. This allows DCM patients to be screened for sequence variants in TTN in parallel with all other known DCM genes and the rest of the coding genome, leading to the third issue: the recent study of TTN truncating variants in DCM1 used a custom NGS panel specific for TTN, and therefore neither the role of genetic variants in other known DCM genes nor segregating variants in novel DCM genes could be assessed. Detailed examination of TTN truncating variants in the context of all coding variants in known and potentially novel DCM genes is needed to assess variant pathogenicity.

In this study we used exome sequence data from seventeen families, each with three or more members affected with DCM, in an effort to identify a genetic cause of DCM, as each family proband was negative for mutations in the coding regions of 16 DCM genes, as previously reported.6–11 From these exome sequences we identified several families with TTN truncating variants. To more carefully assess TTN variants as a cause of DCM, we constructed a linkage map of common informative single nucleotide variants (SNVs) from our exome data in all seventeen families and performed linkage analysis across the genome. We hypothesized that if TTN is causative of 25% of DCM, we would observe a significant combined LOD score across our 17 families at this locus compared to the rest of the genome. Second, we evaluated all other unbiased rare variation in the exome data to identify putative DCM causative variants in each family. We describe the variants identified in TTN in the context of other top ranking variants across the exome sequence of each family. Third, we examined the nucleotide diversity at the TTN locus in the 5,400 exome sequences available from the Exome Variant Server12 to determine if the large amount of variation within this gene is accounted for by size or if the TTN locus is more genetically diverse than other known DCM genes.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Written, informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the Institutional Review Boards at the Oregon Health & Science University and the University of Miami approved the study. The investigation included 17 families, each with three or more members affected with DCM, and with each proband already known to be point mutation negative for 16 known DCM genes.6–11 Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood according to a standard salting out procedure, as previously reported.6–11

Linkage analysis

Two-point and multipoint parametric linkage analysis were performed with the Merlin software13 program. We assumed an affected only model with a disease allele frequency of 0.0001 and penetrance of 0.9. In addition to traditional LOD scores, a HETLOD score resulting from a test of linkage in the presence of genetic heterogeneity was also calculated. A genome-wide linkage map of common informative markers was constructed by identifying all SNV’s present from the exome data that overlap with known SNV’s in 60 unrelated Europeans from the International HapMap. SNV’s with minor allele frequency <1% and / or Mendelian errors within the HapMap were excluded. The remaining markers were then pruned using the PLINK software14 using pairwise r2 <0.1 in sliding windows of 50 SNV’s, moving in intervals of 5 SNV’s. This resulted in a final exome-wide marker set of 4,601 SNV’s. Marker allele frequencies for linkage analysis were determined by the frequency of each SNV in the Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) in the relevant ethnically matched population (either European (n=3,499 individuals) or African American ancestry (n=1,864 individuals).

Exome sequencing and analysis

Exome sequencing was performed at the University of Washington Genome Science Center across seventeen families (48 individuals) with NimbleGen V2 in solution capture and Illumina HiSeq. Sequences were aligned with BWA15 and realignment and single nucleotide and insertion-deletion variants were called with GATK version 1.4, at the Hussman Institute for Human Genomics. Vcf files were then imported into an in-house database, Genomes Management Application (GEMapp) to facilitate storage, variant annotation, querying and analysis. In addition to our exome data, GEMapp was used to store transcriptome data from the left ventricle of four unrelated individuals, two with DCM and two unaffected individuals, as previously published.11 This allowed us to filter variants mapped to genes expressed in heart tissue.

Using GEMapp, we queried each family to determine putative disease-causing variants that met the following criteria: read depth ≥5 and quality scores ≥40; variants that were either missense, nonsense, splice site, or a coding insertion or deletion; shared across all affected members of a family; frequency <0.5% in 5,400 exomes from the Exome Variation Server (EVS); have either a Phastcons16 score >0.4 or a GERP17 score >2; expression in our heart transcriptome dataset with Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads, (RPKM) >3. These criteria were defined from our previous work on 197 variants in known DCM genes published as disease-causing and that was analyzed by our group.18 We also excluded filtered variants that were present in all 48 exomes and variants occurring in more than one family that did not segregate with disease status in at least one other family.

Copy number variation

Copy number variation in 48 DCM exomes was also assessed by the Structural Variant Working Group at the University of Washington, using CoNIFER (Copy Number Inference From Exome Reads, http://conifer.sourceforge.net/).19 A total of 200 non-DCM exomes and 48 DCM exomes were used. Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) transformation was used to remove systematic bias, removing 8 components. The final SVD-ZRPKM signal was then smoothed and the duplication/deletion breakpoints found using a threshold of ±1.5 SVD-ZRPKM.

Sanger sequencing validation

All variants passing filter criteria and occurring within TTN were validated with Sanger sequencing and run on a 3130xl as previously published.11 Primer sequences are shown (Supplementary Table 1). Any additional DNA samples (n=29) from affected and unaffected family members were also sequenced for these variants.

Nucleotide diversity

A total of 316 exons in TTN were targeted in our exome sequence. To assess the genetic variation at this locus, accounting for the large amount of coding sequence, we used the normalized number of variant sites, θ, as a measure of nucleotide diversity across the 5,379 exomes available from the Exome Variant Server. θ was calculated as described in Cargill et al for all coding sequence and also separately for both missense and truncating variants.20

Results

Exome-wide linkage analysis across seventeen families with DCM

The maximum LOD score across the genome and the LOD score at the TTN locus are shown for each family (Table 1). In those families with TTN truncating variants identified by exome sequencing analysis, the maximum LOD score achieved across the genome for each family was comparable to the LOD score at the TTN locus (Table 1). The highest multipoint peak within the genome fell in the region spanning chromosome 9q21.11-q22.31 (hg19:71,862,987–95,840,256), producing a heterogeneity LOD score of 1.74. Overall, in the seventeen families, the TTN locus was the second highest (HLOD=1.59; Table 2).

Table 1.

Genome-wide linkage and rare variant exome sequence analysis summary by family.

| Family | mlod | hg19 region |

TTN mlod |

number filtered exome variants (TTN variants) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedigrees with segregating TTN truncating variants | ||||

| A | 1.178 | chr19:57802806–58058739 | 0.722 | 1 (TTN Arg13527stop) |

| B | 0.899 | chr11:1782594-5625847 | 0.725 | 6 (TTN Ser19378stop, Ile2686Val) |

| C | 0.902 | chr6:35477032–42666164 | 0.034 | 12 (TTN IVS 275+2 T>A) |

| D | 0.602 | chr18:6890434–7017322 | 0.444 | 34 (TTN IVS 275+2 T>A, Gly29127Arg) |

| E | 0.301 | N/A* | 0.283 | 28 (TTN Val28259SerfsX22) |

| F | 0.301 | N/A* | 0.236 | 24 (TTN Lys28880AsnfsX8) |

| G | 0.601 | chr11:290816–6891605 | 0.544 | 24 (TTN Arg31175stop) |

| Other pedigrees without segregating TTN truncating variants | ||||

| Family 8 | 0.901 | chr10:62863518–64597506 | −2.173 | 10 |

| Family 9 | 0.474 | chr5:137754695–137426447 | N/A | 16 |

| Family 10 | 0.601 | chr11:62863518–64597506 | −N/A | 18 |

| Family 11 | 0.301 | N/A* | 0.296 | 22 |

| Family 12 | 0.602 | chr22:29456733–35660875 | N/A | 29 |

| Family 13 | 0.301 | N/A* | −0.347 | 36 |

| Family 14 | 0.301 | N/A* | −0.305 | 43 |

| Family 15 | 1.242 | chr10:99504630–100219374 | N/A | 43 |

| Family 16 | 0.301 | N/A* | −1.238 | 51 |

| Family 17 | 0.301 | N/A* | −0.66 | 80 |

mlod, multipoint lod score across genome; TTN mlod, multipoint lod score at TTN locus; number filtered exome variants refers to the number top ranking variants from exome pipeline with annotation of all top ranking truncating and missense variants in TTN; N/A, not applicable because SNV’s at TTN locus were uninformative for linkage.

N/A* is not applicable, in that more than one region had the same mlod score. Pedigrees A-G and 8–14 had three and pedigrees 15–17 had two affected family members respectively, who underwent exome sequencing.

Table 2.

Top five positive linkage regions in seventeen DCM families

| chr | hg19 start | hg19 end | maximum HLOD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 71,862,987 | 95,840,256 | 1.743 |

| 2 | 174,128,513 | 215,820,013 | 1.588 |

| 6 | 311,938 | 6,318,795 | 1.304 |

| 3 | 336,508 | 16,268,974 | 1.11 |

| 5 | 94,994,339 | 138,456,815 | 1.072 |

HLOD, heterogeneity LOD score. TTN locus in bold.

Exome sequence analysis from seventeen families with DCM

Our criteria for putative DCM variants identified in the exome sequences was based on defined criteria (Methods) and as previously described.11 The number of shared variants meeting these criteria present in each family ranged from 1–80, (average 28.1, median 24). We had previously reported that of the 197 variants already published as causative of DCM, 16% were present in 2,400 exomes from the Exome Sequencing Project, and of those with functional data (and therefore presumed to be pathogenic variants of very low frequency), the median frequency in the Exome Sequencing Project population was 0.04%.18 Applying this maximum 0.04% frequency criterion to the current exome analysis, the number of shared filtered variants per family ranged from 1–49, (average 16.8, median 15).

CNV analysis using exome data did not identify any shared rare variants (frequency < 1% in the ESP dataset) across these families.

A total of six TTN truncating variants (two frameshift, three nonsense and 1 splice variant that occurred in two DCM families) were identified among the filtered candidates in seven of our 17 families (41%) (Table 3). Our approach to identifying which of these truncating variants were likely disease-causing within these families was to genotype them in additional DNA samples in the extended families where possible to assess segregation of the variant with disease, and we also consider them in the context of the additional shared variants in our filtered lists for each family. We further observed from our linkage data that those families with highly negative LOD scores at the TTN locus had no TTN truncating variants that passed our exome analysis filtering criteria. In addition, we screened against presence in the 1000 genomes data (which is independent of the EVS dataset). None of the six truncating variants were present in this dataset.

Table 3.

TTN filtered variants identified in exome analysis and validated with Sanger sequencing that segregated in families with DCM.

| hg19 position | Family ID | Variant function class |

Phast Cons |

GERP | Gran- tham |

additional filtered variants in family |

MAF % (EA) |

MAF % (AA) |

cDNA | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Truncating | ||||||||||

| chr2:179481235 | A: F128 | stop-gained | 1.00 | 3.90 | N/A | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.03 | c.40579C>T | Arg13527stop |

| chr2:179447693 | B: F533 | stop-gained | 1.00 | 5.02 | N/A | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 | c.58133C>G | Ser19378stop |

| chr2:179424036 | C: F27 | splice-5 | 0.99 | 5.61 | N/A | 11 (8) | 0 | 0 | N/A | IVS 275+2 T>A |

| chr2:179424036 | D: F40 | splice-5 | 0.99 | 5.61 | N/A | 32 (17) | 0 | 0 | N/A | IVS 275+2 T>A |

| chr2:179413874 | E: F2B | frameshift | N/A | N/A | N/A | 27 (14) | 0 | 0 | c.84774insT | Val28259SerfsX22 |

| chr2:179411904 | F: F19 | frameshift | N/A | N/A | N/A | 23 (18) | 0 | 0 | c.86640delAGAA | Lys28880AsnfsX8 |

| chr2:179400115 | G: F35 | stop-gained | 1.00 | 4.64 | N/A | 23 (10) | 0 | 0 | c.93523C>T | Arg31175stop |

| Missense | ||||||||||

| chr2:179635998 | B: F533 | missense | 0.98 | 2.44 | 29 | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 | c.8056A>G | Ile2686Val |

| chr2:179410975 | D: F40 | missense | 1.00 | 5.66 | 125 | 32 (17) | 0 | 0.06 | c.87379G>A | Gly29127Arg |

Conservation scores are given as PhastCons and GERP. MAF%, % minor allele frequency from 5,379 exomes in Exome Variant Server (EVS), given in European (EA) and African American (AA) populations. The number of additional filtered variants in other genes identified in each family with a TTN variant are given, and in parentheses, number of variants under more stringent filtering criteria of <0.05% in the EVS.

Clinical characteristics families with DCM and segregating TTN variants

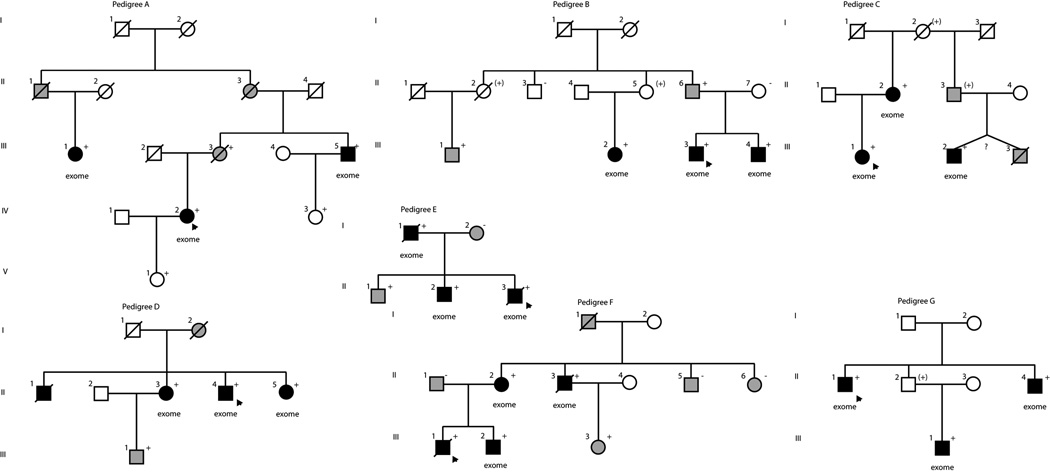

The pedigree structures are shown (Figure 1) and the clinical characteristics of relevant family members are provided (Table 4) of the DCM families with segregating TTN variants (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of families with DCM. Squares represent males, circles females. Diagonal lines mark deceased individuals. Solid symbols denote DCM. Gray symbols represent any cardiovascular abnormality. Open symbols represent unaffected individuals or individuals with no data available for analysis. The presence or absence of the family’s TTN truncating variant is indicated by a + or − symbol, respectively; obligate carriers are noted in parenthesis, (+), unknown zygosity, (?). Individuals who underwent exome sequencing are denoted (exome).

Table 4.

Clinical Characteristics

| Subject | Age at diagnosis, screening or family history information, years |

Gender | DCM | ECG/ Arrhythmia |

LVEDD, mm (Z-score) |

LV septum, posterior wall thickness, mm |

EF or FS, % |

TTN truncating mutation present (yes, no) |

Other mutation? (genotype) |

Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedigree A: Arg13527X | ||||||||||

| IV-2 | 42 | F | yes | PVCs | 56, NA | NA | 20 | yes | ||

| III-1 | 43 | F | yes | 54 (2.44) | NA, 11 | 40 | yes | |||

| III-3 | 69 | F | no | anterior MI | 54, NA | 11, 10 | 42 | yes | CAD diagnosis at age 69 | |

| III-5 | 51 | M | yes | PVCs, AF | 67 (4.04) | NA | 35 | yes | ||

| IV-3 | 27 | F | no | yes | history: paroxysmal atrial tachycardia and syncope | |||||

| V-1 | 23 | F | no | yes | records documenting normal echocardiogram | |||||

| Pedigree B: Ser19378X | ||||||||||

| III-3 | 29 | M | yes | PVCs | 56 (1.54) | 10, 10 | 47 | yes | TTN Ile2640Val | |

| II-2 | NA | F | no | obligate carrier | obligate carrier of TTN Ile2640Val | history: died at 76 from cancer | ||||

| II-3 | 66 | M | no | no | history: normal cardiac screening | |||||

| II-5 | 70 | F | obligate carrier | obligate carrier of TTN Ile2640Val | history: heart attack at age 50–60. | |||||

| II-6 | 64 | M | no | 56 (1.42) | 9, 8 | 49.5 | yes | TTN Ile2640Val | Borderline systolic dysfunction | |

| II-7 | 62 | F | no | 42 (−1.15) | 10, 10 | 39 (FS) | no | |||

| III-1 | 43 | M | no | ICD | yes | TTN Ile2640Val | CAD diagnosis at age 43 | |||

| III-2 | 47 | F | yes | PVCs, bigeminy | 64 (5.21) | 8, 6.8 | 21 | yes | TTN Ile2640Val | |

| III-4 | 36 | M | yes | ICD, PVCs | 64 (3.43) | 9, 10 | 24.5 | yes | TTN Ile2640Val | |

| Pedigree C: IVS 275+2 T>A | ||||||||||

| III-1 | 37 | F | yes | NSSTT | 68 (5.6) | NA | 40 | yes | Right deltoid muscle biopsy due to history of muscle weakness revealed congenital type I fiber predominance or chronic neurogenic atrophy with reinnervation. | |

| I-2 | NA | F | obligate carrier | history: died at 65 from cancer | ||||||

| II-2 | 52 | F | yes | NSSTT | 57 (3.29) | 11, 11 | 22 | yes | ||

| II-3 | 59 | M | no | obligate carrier | death certificate: VT, CAD | |||||

| III-2 | 39 | M | yes | PVCs, LAE, NSSTT | 73 (4.69) | 10, 10 | 32 | yes | ||

| Pedigree D: IVS 275+2 T>A | ||||||||||

| II-4 | 39 | M | yes | AF, cardioversion | 66 (3.58) | 11, 11 | 39 | yes | TTN Gly29127Arg | |

| II-3 | 49 | F | yes | PVCs, PACs, MI | 58 (3.56) | 10, 10 | 25 (FS) | yes | TTN Gly29127Arg | |

| II-5 | 46 | F | yes | NSSTT | 53 (2.26) | 8, 8 | 46 | yes | TTN Gly29127Arg | |

| III-1 | 32 | M | no | RBBB, MI | 51 (−0.07) | 8, 8 | 41 | yes | ||

| Pedigree E: Val28259SerfsX22 | ||||||||||

| II-3 | 14 | M | yes | 75 (6.30) | 5, 8 | 13 (FS) | yes | heart transplantation | ||

| I-1 | 44 | M | yes | LAHB, MI, NSSTT | 62 (3.06) | 10, 9 | 25 | yes | ||

| I-2 | 42 | F | no | normal | 55 (2.32) | 8, 9 | 60 | no | MYBPC3 Ala833Thr | |

| II-1 | 20 | M | no | normal | 60 (2.28) | 10, 9 | 60 | yes | ||

| II-2 | 22 | M | yes | AF, ICD | 63.5 (3.01) | 10, 7 | 20 | yes | MYBPC3 Ala833Thr | heart transplantation |

| Pedigree F: Lys28880AsnfsX8 | ||||||||||

| III-1 | 16 | M | yes | AF, NSSTT | 21 | yes | cardiomegaly (CXR); heart transplantation. Died post transplant, age 21. | |||

| II-1 | 47 | M | no | normal | 52 (0.28) | 12, 9 | 83 | no | ||

| II-2 | 45 | F | yes | NSSTT | 51 (1.78) | NA | 48 | yes | ||

| II-3 | 52 | M | yes | AF, NSCD, cardioversion | 50 (NA) | 8, 9 | 35 | yes | Death from non-cardiovascular cause | |

| II-5 | 52 | M | no | 1AVB | 50 (−0.22) | 9, 10 | 77 | no | ||

| II-6 | 41 | F | no | MI, NSSTT | 55 (2.97) | 6, 8 | 68 | no | ||

| III-2 | 20 | M | yes | ICD, tachycardia | 60 (2.55) | 8, 6 | 38 | yes | heart transplantation | |

| III-3 | 25 | F | no | normal | 51 (0.53) | 7, 7 | 47 | yes | ||

| Pedigree G: Arg31175X | ||||||||||

| II-1 | 52 | M | yes | 56 (NA) | NA | 10 | yes | |||

| II-2 | M | obligate carrier | By history: no known heart problems | |||||||

| II-4 | 49 | M | yes | LAE, tachycardia, NSSTT | 70 (5.04) | 12, - | FS 17 | yes | ||

| III-1 | 35 | M | yes | LAE, tachycardia, NSSTT | 69 (5.21) | 10, 9 | 20 | yes | ||

1AVB, first degree atrioventricular block; AF, atrial fibrillation; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; ECG, electrocardiogram; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; LAE, left atrial enlargement; LAHB, left anterior hemiblock; LV, left ventricle; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; MI, myocardial infarction pattern; NA, not available; NSCD, non-specific conduction delay; NSR, normal sinus rhythm; NSSTT, non-specific ST-T changes; PAC’s, premature atrial contractions; PVC’s, premature ventricular contractions; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Family A

Family A had DNA samples available for three additional members. Sanger sequencing showed that all six family members were heterozygous for the truncating variant. Subject III.3, a female who carried the TTN variant, died at age 69 with mild systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction of 42%) but without left ventricular enlargement (LVE), having suffered an myocardial infarction in her 50’s, and thus confounding assessment of whether the TTN variant, the myocardial infarction, or both contributed to her systolic dysfunction. Two subjects (IV.3, V.1), both mutation carrier’s in their 20’s, had no evidence of DCM.

Family B

In addition to the three samples that had exome sequencing, Family B had DNA samples available from six other family members. Sanger sequencing confirmed the nonsense variant as present in all affected family members. A female obligate carrier (II.2) died of cancer at age 76 without a cardiovascular history. Another female obligate carrier (II.5) had no cardiovascular history at age 70. A male who carried the TTN variant at age 69 (II.6) had only borderline systolic dysfunction without LVE.

Family C

Only three DNA samples were available for this family and were used for exome sequencing. Subject III.3, who died of DCM, was an identical twin by family history and thus may have been an obligate carrier. Another obligate carrier (III.3) had no known DCM but by death certificate died of ventricular tachycardia and coronary artery disease. None of the additional twelve variants passing filtering criteria (eight under more stringent filtering of population frequency <0.05% in the ESP exome dataset) occurred in known DCM or other cardiomyopathy associated genes.

Family D

This family of European ancestry carried the same TTN splice variant identified in Family C. Of the additional 32 variants also identified as putative disease-causing in this family, only one occurred in a known DCM gene, a missense variant in TTN, chr2:179,410,975, NM_133378.4, Gly29127Arg.

Family E

This family carried a single base insertion in TTN resulting in a frameshift mutation. Of the additional 26 segregating variants also identified in this family, the only variant in a gene with a reported association with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy occurred in SOS1.21 One of the affected children (II.2) carried a rare variant in MYBPC3 inherited from his mother (I.2), previously reported by us as likely disease-causing9 but suggested to be of unknown significance based on a subsequent study;22 we also note that this variant is present at a frequency 0.12% in the EVS, making it more common than many DCM rare variants.18

Family F

A four bp deletion in TTN resulted in a frameshift mutation. DNA was available from one additional affected member and three unaffected family members, and the TTN variant was confirmed to be present in all four affected members by Sanger sequencing and was not present in the three unaffected members. None of the other 23 segregating variants identified occurred in known cardiomyopathy-associated genes.

Family G

No DNA samples beyond those used for exome sequencing were available to assess segregation in this family. Of the additional 23 variants that segregated, none occurred in other cardiomyopathy-associated genes.

Segregating missense variants at the TTN locus

We also considered the implication of segregating TTN missense variants passing our exome filtering pipeline as a class of variants that were not discussed in the recent TTN paper.1 Determination of pathogenicity of these variants will be extremely challenging because of the large number of coding exons. In the 5,400 ESP exome datasets, the average number of TTN missense variants per individual was 23.3, ranging 6 to 55. These were comparable results to those observed in the exome sequences of our DCM families, with the average number of TTN missense variants per DCM individual at 22.75, (ranging 11 to 43). Application of our DCM filtering criteria to missense variants in the 5,400 ESP exomes (frequency <0.5% and either a PhastCons score >0.4 OR a GERP score of >2) resulted in an average of 1.91 missense variants per individual (ranging 0 to 23). Five TTN missense variants passed our exome filtering approach (that segregated with all individuals affected with DCM in a family): one each in two DCM families who also had segregating truncating variants (Table 3), and the others in two families, each with high quality candidates in known cardiomyopathy genes so they were not further prioritized. The average number of TTN missense variants without regard to sharing, that is, an analysis of only one individual from each of the 17 families, a less stringent approach and similar to the analysis of all missense TTN variants conducted for the EVS, was 1.88.

Non-segregating, truncating variants

Given the observed excess of TTN truncating variants in both familial and in sporadic DCM verses controls,1 we thought it also relevant to report the number of non-segregating truncating variants in TTN identified in the exome sequences of these 48 individuals with DCM, as these may be potential susceptibility variants. We observed two non-segregating TTN truncating variants that were validated with Sanger sequencing. First, a C insertion at hg19 chr2:179,426,992 generating a frameshift in one of three family members with DCM who underwent exome sequencing (Family 14, Table 1), and a nonsense variant at hg19 chr2:179,605,218, NM_003319.4 Gln3885stop in two of three family members (Family 17, Table 1). Neither variant was observed in the 5,400 ESP exome sequences or in the 1000 Genomes data, making them potential susceptibility variants. In the case of the frameshift variant, this family had already been shown to segregate a variant published as disease-causing accompanied by functional data6 and in Family 14 with the nonsense variant, a total of 43 segregating variants were identified by our exome filtering pipeline (Table 1), none of which were in previously published cardiomyopathy genes.

Nucleotide diversity of TTN

The NimbleGen V2 in solution capture target included 315 discrete exons from six TTN transcripts (NM_001256850.1, NM_133432.3, NM_133378.4, NM_003319.4, NM_133437.3 and NM_133379.3), totaling 110,459 bp coding sequence. Our exome pipeline identified TTN truncating variants in seven DCM families. This could simply be a result of the large number of exons. Hence, we investigated the nucleotide diversity at the TTN locus in a non-DCM population. The Exome Variant Server (EVS) contains annotated exome sequence from 5,379 individuals at the TTN locus totaling 2,425 and 25 discrete missense and nonsense variants, respectively. Across 5,379 EVS individuals there are a total of 125,575 missense alleles and 77 nonsense alleles, averaging 23 and 0.014 per individual, respectively. We calculated the normalized number of variant sites, θ 20, accounting for sample size and the number of coding bases in the EVS individuals at the TTN locus to be 2.23×10−3 and 2.3×10−5 for missense and nonsense variants respectively. The same calculation across five other known DCM genes (MYBPC3, TNNC1, TNNI3, MYH6 and TPM1) in the EVS data gave comparable results to those observed in TTN, (for missense variants, θ ranged from 6.9×10−4 at TPM1 to 1.05×10−3 at TNNC1 and for truncating variants, 0 at TNNC1 and TNNI3 to 1.29×10−4 for MYBPC3), suggesting that the excess of shared truncating variants in our DCM families is not due to the large number of exons alone and that nucleotide diversity at TTN is comparable to other known DCM genes.

Discussion

This is the first independent replication study of TTN truncating variants as frequently involved in the pathogenesis of familial DCM. Herman et al recently identified TTN truncating mutations in 25% of familial DCM and 18% of sporadic DCM, a significant excess compared to 3% of controls.1 The authors concluded that truncating mutations in TTN are a frequent cause of DCM, as all prior reports of unselected patients with DCM of unknown cause ranged from <<1% to 5–8%.4 However, 3% of controls in the Herman et al publication1 also were observed to have TTN truncating variants, suggesting that the interpretation of specific TTN truncating variant pathogenicity would be challenging, especially in simplex cases. Analysis across nineteen DCM families segregating rare TTN truncating variants in the Herman et al study1 yielded a combined LOD score of 11.1, providing strong evidence that the truncating variants in those families were pathogenic. However, in that study TTN was sequenced in isolation so that the relevance of the linkage evidence in the TTN region could not be compared to the rest of the genome.

We hypothesized that if rare variants in TTN indeed account for one-quarter of familial DCM, this locus should also be detected using an unbiased genome-wide linkage approach across our 17 DCM families, as they should be enriched for causative variants at this locus, especially since the DCM families in this study were selected for exome sequencing because they were already known to be point mutation negative for 16 other known DCM genes6–11 (with the exception of one family segregating a previously described variant 6 in a gene attributing ~0.5% of DCM). Genome-wide linkage analysis yielded the second most significant evidence of linkage at the TTN locus compared to other regions in the genome, which we interpret as evidence of the TTN locus in DCM pathogenesis.

Next we identified those nonsense, missense, splice and frameshift variants in the exome sequences, meeting our filtering approach that included conservation and myocardial expression, which segregated with DCM affection status in each family. Seven of 17 families (41%) had segregating TTN truncating variants identified in their filtered exome variants. Using common informative SNV’s within the exome sequences, the combined LOD score at the TTN locus for these seven families was 2.99, and in each family the maximum LOD score at the TTN locus was either the maximum LOD score achieved in that family across the whole exome or comparable to the maximum observed LOD score at any other locus. We interpret these data as replication of TTN truncating variants as frequently linked with DCM.

Despite the previous evidence1 and our findings presented here, all which collectively support the concept that TTN truncating variants are highly relevant for DCM pathogenesis, determining the pathogenicity of any specific variant remains extremely challenging. We interpret the 2 truncating variants not shared by all affected family members in two families (Families 14 and 17) as unlikely to be causative of DCM. We also note that in the 7 families where all those affected with DCM carried a truncating variant, some unaffected members at older ages also carried the same truncating variant. This observation confounds pedigree analysis even though it is consistent with reduced penetrance, which is commonly observed with familial DCM. Further, the plethora of TTN missense variants observed in all individuals, whether from control or DCM cohorts, further complicates TTN variant interpretation. The available evidence from the ESP data has shown that most individuals will carry numerous TTN missense variants, some even very rare, and even if such variants segregate with DCM in a family, this may occur as a play of chance. This concept may also apply to truncating variants.

These issues raise two central questions of TTN biology in DCM. Which specific variants, whether truncating or missense, play a role in DCM pathogenesis? Do TTN variants include causative as well as risk alleles? Titin splicing and titin biology are exceedingly complex,23, 24 and penetrance is well known to be incomplete and expressivity variable in familial DCM,4, 5 so it is possible if not likely that some TTN variants, whether missense or truncating, may also modulate penetrance and expressivity in DCM. Addressing these questions will require much larger DCM cohorts with detailed phenotypic data, ideally with knowledge of extended family structure (including presymptomatic DCM), genome-wide sequence data, and comprehensive, insightful analysis of the pathophysiological effects of TTN variants.

Though linkage analysis has been less frequently utilized in the GWAS era, our study highlights the importance of coupling linkage information with sequence data. This provides us both a measure of evidence for a cumulative effect of rare variants, since linkage is not compromised by allelic heterogeneity (i.e., multiple rare disease variants within a gene), and an assessment of the evidence in the context of the rest of the genome. Together, linkage analysis and sequencing provide complementary evidence that can improve the efficiency of gene discovery in sequencing studies.

The observation that 7 of 17, or 41%, of families with TTN truncating variants that segregated with DCM is higher than the 25% frequency observed in families with DCM the Herman et al study.1 This most likely resulted from a sample bias in our study because our families were already known to be point mutation negative for 16 other known DCM genes, and thus were likely enriched for TTN variants.

We also examined TTN missense variants in our seventeen families using an unbiased approach to exome analysis and additional data from >300 exomes with neurological phenotypes collated in our in-house database, GEMapp. Our calculation of nucleotide diversity in the Exome Sequencing Project dataset for this gene suggested that diversity at the TTN locus was comparable to other known DCM genes relative to the number of coding nucleotides. However, the >300 TTN exons resulted in a very large number of missense variants identified in both the exome sequence from individuals with DCM and individuals in the ESP dataset. Two TTN missense variants from two DCM families, both also carrying TTN truncating variants, passed our exome filtering criteria. We considered these two missense variants (Gly29127Arg and Ile2685Val) of unknown significance, as each met our stringent exome filtering criteria and were not present in over 300 other exomes in GEMapp but occurred in Families B and D that also had TTN truncating variants.

We also note that the most highly linked region in this study on chromosome 9q21.1-q22.31 did not contain any known DCM genes and that none of our filtered genes mapped to this region. The positive linkage at this region could be a chance finding. Alternatively, this could represent a region of the genome containing a novel DCM gene missed by our exome pipeline for two possible reasons. Our rare variant exome analysis approach is based on assumptions, based on our previous work.18 Firstly, we assumed that causative rare variants were missense, nonsense, splice or frameshift and the allele frequency of these variants would be <0.5%. We note here that the majority of known (published) DCM variants are significantly less frequent than 0.5% in the general population18 but there are examples of known DCM variants with convincing functional data where the variant frequency is very close to this cut-point (CSRP3 Trp4Arg variant25 has a frequency of 0.35% in European ancestry EVS dataset). Whilst this variant would have been identified in our pipeline, it is possible that other pathogenic variants have frequencies slightly greater than this. Secondly, our genome-wide linkage approach could also have identified regions containing common susceptibility or modifying variants, again that would not have been detected by our exome analysis approach. We note recent prior evidence of linkage to congenital heart defects and low atrial rhythm to this region,26 suggesting the possibility of cardiovascular modifying variants located here.

In conclusion, our data show that TTN was the only gene with implicated rare variants that occurred in multiple DCM families, and hence, have replicated the prior finding1 that TTN truncating variants do contribute frequently to DCM pathogenesis. We reiterate that TTN analysis for DCM causation should be considered within the context of the genome. While interpreting individual TTN truncating or missense variants will remain challenging due to the complexity of TTN biology, the availability of sequencing data from known DCM genes and variants at other exomic loci will assist in categorizing the pathogenicity of these variants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the family members who participated, without whom this study would not be a success. The authors would like to thank the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project which produced exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL-102923), the WHI Sequencing Project (HL-102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL-102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL-102926) and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL-103010). The authors would like to thank the ESP Family Studies Project Team: Sek Kathiresan, Jay Shendure, Mike Bamshad, Weiniu Gan, Rebecca Jackson, Ani Manichaikul, Christopher Newton-Cheh, Debbie Nickerson, Stephen Rich, Jerry Rotter, and James Wilson.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by NIH awards HL58626 (Dr Hershberger), HL094976 (Dr Nickerson, Seattle Seq).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MR, Wang L, Teekakirikul P, Christodoulou D, et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:619–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerull B, Gramlich M, Atherton J, McNabb M, Trombitas K, Sasse-Klaassen S, et al. Mutations of TTN, encoding the giant muscle filament titin, cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2002;14:201–204. doi: 10.1038/ng815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerull B, Atherton J, Geupel A, Sasse-Klaassen S, Heuser A, Frenneaux M, et al. Identification of a novel frameshift mutation in the giant muscle filament titin in a large Australian family with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Mol Med. 2006;84:478–483. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershberger RE, Siegfried JD. State of the Art Review. Update 2011: clinical and genetic issues in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1641–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershberger RE, Morales A, Siegfried JD. Clinical and genetic issues in dilated cardiomyopathy: A review for genetics professionals. Genetics in Medicine. 2010;12:655–667. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f2481f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li D, Parks SB, Kushner JD, Nauman D, Burgess D, Ludwigsen S, et al. Mutations of presenilin genes in dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1030–1039. doi: 10.1086/509900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parks SB, Kushner JD, Nauman D, Burgess D, Ludwigsen S, Peterson A, et al. Lamin A/C mutation analysis in a cohort of 324 unrelated patients with idiopathic or familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2008;156:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hershberger RE, Parks SB, Kushner JD, Li D, Ludwigsen S, Jakobs P, et al. Coding sequence mutations identified in MYH7, TNNT2, SCN5A, CSRP3, LBD3, and TCAP from 313 patients with familial or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin Translational Science. 2008;1:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershberger RE, Norton N, Morales A, Li D, Siegfried JD, Gonzalez-Quintana J. Coding sequence rare variants identified in MYBPC3, MYH6, TPM1, TNNC1, and TNNI3 from 312 patients with familial or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:155–161. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.912345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li D, Morales A, Gonzalez Quintana J, Norton N, Siegfried JD, Hofmeyer M, et al. Identification of novel mutations In RBM20 in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin Trans Sci. 2010;3:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norton N, Li D, Reider MJ, Siegfried JD, Rampersaud E, Zuchner S, et al. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [cited 2012 August 8, 2012];Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA. Available from: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/.

- 13.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin--rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siepel A, Bejerano G, Pedersen JS, Hinrichs AS, Hou M, Rosenbloom K, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper GM, Stone EA, Asimenos G, Green ED, Batzoglou S, Sidow A. Distribution and intensity of constraint in mammalian genomic sequence. Genome Res. 2005;15:901–913. doi: 10.1101/gr.3577405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norton N, Robertson PD, Rieder MJ, Zuchner S, Rampersaud E, Martin E, et al. Evaluating Pathogenicity of Rare Variants From Dilated Cardiomyopathy in the Exome Era. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2012;5:167–174. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumm N, Sudmant PH, Ko A, O'Roak BJ, Malig M, Coe BP, et al. Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cargill M, Altshuler D, Ireland J, Sklar P, Ardlie K, Patil N, et al. Characterization of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in coding regions of human genes. Nat Genet. 1999;22:231–238. doi: 10.1038/10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts AE, Araki T, Swanson KD, Montgomery KT, Schiripo TA, Joshi VA, et al. Germline gain-of-function mutations in SOS1 cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakdawala NK, Funke BH, Baxter S, Cirino AL, Roberts AE, Judge DP, et al. Genetic testing for dilated cardiomyopathy in clinical practice. J Card Fail. 2012;18:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo W, Bharmal SJ, Esbona K, Greaser ML. Titin diversity--alternative splicing gone wild. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;753675:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2010/753675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel JR, Pleitner JM, Moss RL, Greaser ML. Magnitude of length-dependent changes in contractile properties varies with titin isoform in rat ventricles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H697–H708. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00800.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knoll R, Hoshijima M, Hoffman HM, Person V, Lorenzen-Schmidt I, Bang ML, et al. The Cardiac Mechanical Stretch Sensor Machinery Involves a Z Disc Complex that Is Defective in a Subset of Human Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Cell. 2002;111:943–955. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van de Meerakker JB, van Engelen K, Mathijssen IB, Lekanne dit Deprez RH, Lam J, Wilde AA, et al. A novel autosomal dominant condition consisting of congenital heart defects and low atrial rhythm maps to chromosome 9q. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:820–826. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.