Abstract

Background

Postpartum physical health problems are common and have been understudied. This study explored the relationship between reported physical symptoms, functional limitations and emotional well-being of postpartum women.

Methods

The study involved data from interviews conducted at 9-12 months postpartum from 1,323 women who had received prenatal care at 9 community health centers located in Philadelphia, Pa. (February 2000 and November 2002). Emotional well-being was assessed with the CES-D Scale and perceived emotional health. Functional limitations measures were related to child care, daily activities (housework, shopping), and work. A summary measure of postpartum morbidity burden was constructed from a checklist of potential health problems typically associated with the postpartum period, such as backaches, abdominal pain, and dyspareunia.

Results

More than two-thirds (69%) of the women reported experiencing at least one physical health problem since childbirth. Forty-five percent reported at least one problem of moderate or major (as opposed to simply minor) severity, and 20 percent reported at least one problem of major severity. The presence, severity and cumulative morbidity burden associated with postpartum health problems was consistently correlated with reports of one or more functional limitations, and measures of emotional well-being, including depressive symptomatology.

Conclusions

Although physical problems typically associated with the postpartum period are often regarded as transient or comparatively minor, they are strongly related to both the functional impairment and poor emotional Health. Careful assessment of the physical, functional, as well as emotional health status of women in the year following childbirth may improve the quality of postpartum care.

Keywords: postpartum health, postpartum depression, functional limitations, urban low-income mothers

Historically, obstetrical outcomes research has focused mainly on maternal and neonatal mortality, or life-threatening and serious illnesses resulting in hospitalization during pregnancy or following childbirth (1-8). A small number of more recent studies have addressed a much wider range of health problems that childbearing women may experience in the postpartum period – including, for example, backaches, headaches, fatigue, and perineal or pelvic pain. Albers has referred to this category of health problems as the “hidden morbidity” (1). Empirical findings suggest that such problems are quite common and can persist over time, and thus should be regarded as having considerable importance for the functional health status and the overall quality of life of women, during the postpartum period (3,9-14). The absence of better information about the extent and nature of this hidden morbidity has been identified by patients as a significant problem, since women are surprised by and may be unprepared to deal with the attendant discomfort and limitations. Similarly, obstetrical providers see the lack of epidemiological data as a significant barrier to the provision of optimal postpartum care (3).

While awareness of the scope, prevalence and persistence of postpartum morbidity has improved, further research is needed to reveal its causes, correlates and consequences (13). Emotional health, for example, has been the subject of longstanding concern in obstetric and psychological literature (15-20), but surprisingly there are no known large-scale studies in the U.S. examining the link between the varying degrees and types of physical morbidity and depression or depressive symptoms in the postpartum period. This is in spite of well-documented comorbidity of physical illnesses, and depressive and emotional disorders in the wider adult and elderly populations,(21-25) which has arguably informed practice in ways that have improved the quality of care.

The current study explores the relationships between postpartum physical health, functional impairment and the emotional well-being of postpartum women. Specifically, data from a community-based observational study are examined to determine the associations between some of the more commonly occurring postpartum morbidities, the presence of work, child care, daily activity functional limitations, depressive symptomatology, and overall self-rated emotional health of new mothers in the study sample.

METHODS

This research was part of a larger, prospective, community-based study examining maternal stress, birth outcomes, and maternal and infant health and health-related behaviors. The larger study involved recruitment of women who first enrolled for prenatal care at a consortium of six community health centers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, between February 2000 and November 2002. The larger study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, and approved by the institutional review boards at Thomas Jefferson University and the University of Pennsylvania. Additional findings from and more details about the study are available from several articles in press, and published in other peer-reviewed journals (15, 26-32). The study involved an initial interview at the time of enrollment for prenatal care and three follow-up surveys in the subjects’ homes at approximately 3-4 months postpartum, 9-12 months postpartum, and at 22-24 months postpartum.. Ninety eight percent (98%) of all eligible women approached for recruitment during their pregnancy agreed to participate. Women with a singleton, intrauterine pregnancy and who spoke either English or Spanish were considered eligible. With the exception of a few sociodemographic characteristics reported and noted in Table 1, all results presented here are based on data obtained from the third interview only, conducted at 9-12 months postpartum. A total of 79 percent (N=1,323) of the women who enrolled, whose pregnancy ended in a live birth and who were living with their children at the time (the target group for all postpartum surveys: N=1,984) were successfully contacted and interviewed for the 9-12 months postpartum survey. All interviews were based on structured surveys, conducted in English or Spanish by trained female interviewers. To minimize the chances of interviewer bias or misinformation each interviewer received approximately 30 hours of training in use of this instrument, including instruction on when and when not to prompt women for responses, and how to explain the meaning of a question should any misunderstanding arise. The training included role playing, and each interviewer had to be carefully assessed and rated as competent by an experienced project supervisor before assignment to the field. For quality control purposes a ten percent random sample of all completed interviews completed by each interview were routinely reviewed for internal consistency of response items, and to ensure thoroughness, and appropriate use of the instrument. Weekly meetings were held with the interviewers, project staff and principal investigator (Dr. Jennifer Culhane) to discuss any issues related to the interviewing process.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Sample (n =1,323)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Marital Status, single n (%) | 1,058 (85) |

| U.S. Born** N ( % | 1,006 (76) |

| Race/Ethnicitv, n (%) | |

| African American | 933 (70) |

| White | 130 (10) |

| Hispanic | 218 (17) |

| Other | 42 (3) |

| Education, % ** | |

| <High School | 526 (39) |

| High School/GED*** | 802 (61) |

| Parity, primaparous % | 637 ( 48) |

| Method of Deliverv,% * | |

| C-section | 273 ( 21) |

| Assisted Vaginal | 63 (5) |

| Spontaneous Vaginal | 987 (74) |

| Infant’s Birthweight, * | |

| <2500g | 153 (12) |

| 2500-3499g | 847 (64) |

| 3500g or more | 223 (25) |

| Depressive Svmptomatology,% | |

| CES-D < 16 | |

| 17-22 | |

| >23 | |

| Functional Limitations,% | |

| No | |

| Yes | |

| Emotional Well Being,% | |

| Excellent/Good | |

| Fair/Poor | |

| Mean Annual Household Income,** | $8265 |

| Mean Age,** years (SD) | 24 (+6) |

Based on information reported on birth certificate records, which as part of the larger study, that were linked to information from the interviews

Based on information collected at time of first (prenatal) interview

GED refers to Graduate Equivalency Degree

Study Variables

Creation of the study variables was guided by three primary objectives: (1) to assess the prevalence and degree of severity of physical health problems experienced by women in the study sample; (2) to examine the associations between the presence and severity of each of the reported postpartum health conditions, and functional impairment and emotional well-being; and (3) to determine if there is evidence of a cumulative “morbidity burden” of physical problems that is correlated with increased impairment and/or poorer emotional well-being.

Postpartum Health Problems

The survey included a checklist of several health conditions potentially affecting postpartum women -- specifically, those that are generally considered to be either caused or exacerbated by pregnancy or childbirth. The checklist included thirteen possible symptoms: fatigue or tiredness; headaches; nausea or vomiting; backaches; constipation; hemorrhoids; vaginal pain, discomfort, or discharge, other than blood; dyspareunia; abdominal or pelvic pain; frequent urination, the feeling of having to urinate frequently including the inability to make it to the bathroom on time, or inability to control bowel movements; and breast soreness.

For each possible symptom, women were asked the following question by the interviewers: “since childbirth, have any of the following been a problem for you?” If the answer was ‘yes’ respondents were than asked to indicate the severity of the condition. Severity was measured by asking whether the condition represented a minor problem, somewhat of a problem, or a major problem for the respondent following parturition.

The reported presence and severity of specific conditions were used to gauge the extent and nature of postpartum morbidity. To determine whether or not postpartum morbidity might have a cumulative effect on functional impairment or emotional well-being, we constructed a rather straight forward scale, taking into account the number of postpartum conditions reported and the severity scores. Specifically, we calculated an algorithm assigning, zero, one, two, or three “points” for each condition depending on whether it had been reported as having never been a problem, as having been a minor problem, as having been somewhat of a problem, or as having been a major problem, respectively, following parturition. The points were then simply added to assign respondents a total score which we refer to here as the postpartum “morbidity burden scale”. Since this was largely an exploratory analysis, we established the cut-points which appeared to maximize the discrimination in terms of the measures of functional impairment and emotional well-being described below. In the final scheme used in these analyses women were categorized as having no morbidity burden (0 points), low (1 or 2), medium (3-6), or high (7 or more) morbidity burden. Subsequent data analyses, using cut-points defined in terms of quartiles of the scale, yielded very similar results and, therefore, are not presented here.

In order to make the analyses more manageable and meaningful, and based on the recommendations of an interdisciplinary panel comprised of obstetricians, pediatricians, family physicians, and epidemiologists, some reported conditions were grouped together. Specifically, items 1, 2 and 3 in the above checklist were combined so as to reflect the presence of either “fatigue, headaches or nausea;” items 5 and 6 were combined to indicate “constipation or hemorrhoids,” and items 10,11 and 12 were combined to indicate “urinary or bowel conditions.” Factor analyses of the data using all 13 of the original items confirmed that these conditions appear to be clinically related symptoms, amenable to the grouping scheme recommended by the panel (data not presented, but available upon request).

Functional Limitations

Participants were asked three related questions about their functional health status: specifically, if their physical health was currently affecting their ability to work; to care for their children; or to perform general household chores. Based on the responses to these items, functional health status was measured in terms of one or more reported functional limitations related to either work, childcare or everyday household activities.

Emotional Well-being

The survey included the measurement of maternal depressive symptoms using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a pre-tested, reliable and valid instrument used widely in studies of depression, including postpartum depression (15,23). As part of the survey, women were also asked to rate their overall emotional health as currently being “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” or “poor.” This question, too, is widely used in survey protocols to measure mood disorder. For these analyses, emotional well-being was measured by the CES-D and self-rated, overall emotional health. Presence of depressive symptoms was defined as a CES-D score of ≥ 23. This corresponds to the 90th percentile score for community samples and has been used by other investigators to identify depressive symptomatology among pregnant women (33-35). Self-reported ratings of overall emotional health were dichotomized and respondents were classified as being in relatively poor (“fair” or “poor”) vs. good (“excellent,” “very good,” or “good”) emotional health.

Statistical Analyses

We expected the relationships in question would be ordinal in nature -- that is, that increasing levels of severity would be associated with increasing prevalence of functional limitations, depressive symptomotalogy and emotional well being. Goodman and Kruskal’s Gamma is designed specifically to measure the degree of association (positive or negative) between two ordinal level variables by calculating the number of concordant and discordant pairs in the data. Gamma is appropriate, as in this case, where ordinal relationships are hypothesized or indicated, the strength of association between the relative ranking of observations for any set of two variables is of interest, and it is important to establish that the strength of associations is unlikely to be due to chance, or sampling variation alone. Hence, P-values presented in the tables that follow are tests of significance for Gamma, indicating the probability that the Gamma values reflect “chance” as opposed to systematic ordinal-level relationships observed. P-values for Gamma were consistent with those for Chi-square, Sommer’s D, and Kendals tau-b calculations; however, since Goodman and Kruskal’s Gamma is more precise and more appropriate when ordinal relationships are suspected, found to be present, and add to the understanding of the relationships between variables, only the P-values associated with Gamma are presented here. Additional information related to statistical inference procedures, including Gamma, Chi-square or other values is available from the authors upon request

All analyses for the study were conducted in SPSS, version 15.0 (36).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and other relevant characteristics for the 1,323 survey respondents are presented in Table 1. The majority of respondents were single, U.S-born women with low, annual, household incomes and of African American descent. Approximately one-third of the respondents had less than a high school education, and the overall mean age was 24 years. About one-half of our study population were primiparous, one-fifth were delivered by Cesarean section, and only 5 percent had assisted vaginal deliveries. About one out of eight (12%) delivered low birthweight infants.

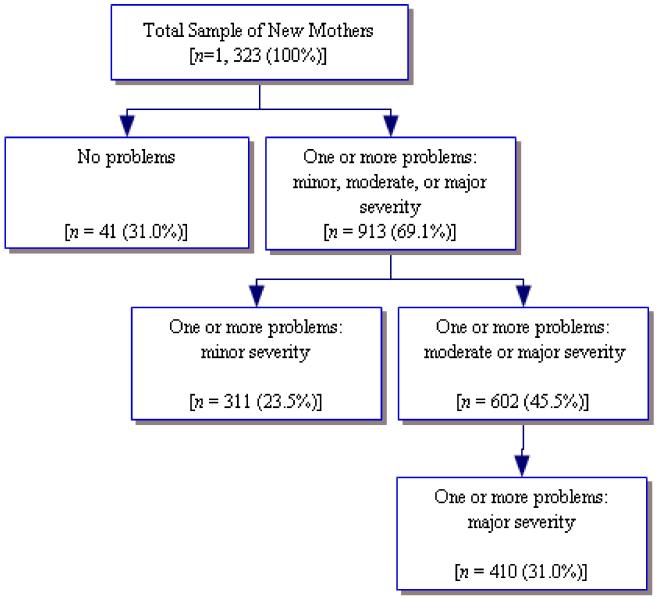

Table 2 shows the frequencies of reported physical health problems by level of severity. About half (51%) of the women reported having experienced fatigue, headaches or nausea since delivery; more than one out of five reported these conditions as having been of moderate (20.2%) or major (7.7%), as opposed to minor (23.1%) severity. Backaches were the only other frequently reported physical problem, with almost one out of four indicating that they were of either moderate (15.2%) or major (9.6%) severity. Although reports of having experienced other physical conditions, especially of moderate or major severity, were relatively rare, reports of having any condition that was more than minor were not so rare. As the results in Table 3 reveal, more than two out of every five women (45.5%) reported having experienced at least one condition of either moderate or major severity (45.5%), and more than one of every five reported having experienced at least one condition of major severity (20.5%). Fewer than one-third (31%) were essentially “symptom free” -- that is, none of the physical conditions on the checklist had presented a problem for them since delivery. It is important to note that these are not mutually excusive categories, and for the purposes of clarity we have presented the complete and detailed breakdown of reported morbidity and severity in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Reported Postpartum Conditions, By Perceived Severity (N=1,323)

| -------- % of Respondents Reporting as -------- | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never a Problem |

Problem of of Minor Severity |

Problem of Moderate Severity |

Problem of of Major Severity |

|

| Problem | ||||

| Fatigue, Headaches, or Nausea | 49.0 | 23.1 | 20.2 | 7.7 |

| Backache | 56.9 | 18.3 | 15.2 | 9.6 |

| Abdominal Pain | 89.0 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 1.9 |

| Vaginal Pain or Dyspareunia | 89.6 | 4.5 | 4.2 | 1.7 |

| Constipation or Hemorrhoids | 87.9 | 6.0 | 3.8 | 2.3 |

| Urinary or Bowel Problems | 85.6 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 3.2 |

| Breast Soreness | 92.1 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 1.3 |

Table 3. Aggregate Postpartum Morbidity, By Severity.

| N (% of Sample) | |

|---|---|

|

Respondents Reporting: |

|

| No Problems | 410 (31.0) |

|

One or more problems:

minor, moderate, or major severity |

913 (69.1) |

|

One or more problems:

moderate or major severity |

602 (45.5) |

|

One or more problems:

major severity |

264 (20.5) |

Figure 1.

Aggregate Postpartum Morbidity by Severity (reported by mothers 9-12 months after childbirth)

The percentages of women reporting functional limitations were consistently and significantly related to postpartum health problems (Table 4). All categories of morbidity were associated with increased frequencies of a reported functional limitation, and those frequencies appeared to increase with the greater severity of the problem experienced by the women.

Table 4. Specific Postpartum Conditions and Functional Limitations.

| --- % With Functional Limitation -- | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never A Problem |

Problem of Minor Severity |

Problem of Moderate or Major Severity |

P –Value * | |

| Condition | ||||

| Fatigue, Headaches, Nausea | 13.7 | 18.0 | 30.4 | 0.001 |

| Backache | 14.6 | 21.9 | 28.4 | 0.001 |

| Abdominal Pain | 17.2 | 35.5 | 37.3 | 0.001 |

| Vaginal Pain or Dyspareunia | 17.2 | 30.0 | 38.5 | 0.001 |

| Constipation or Hemorrhoids | 18.0 | 25.2 | 33.3 | 0.002 |

| Urinary or Bowel Problems | 17.6 | 21.8 | 35.4 | 0.001 |

| Breast Soreness | 17.8 | 40.2 | 34.0 | 0.001. |

The P-values here refer to test of significance levels for Gamma. As explained in the Methods section Gamma is a summary proportional reduction of error measure reflecting the extent to which rankings on two variables are correlated – in this casepostpartum condition and degree of functional limitations. Respondents are implicitly ranked ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’ depending on whether they reported never having the problem, having the problem with only minor severity, or having the problem with moderate/major severity, respectively. They are also implicitly ranked ‘low’ (not present) or ‘high’ (present) for the presence of a functional limitation. If the respective rankings for all possible observation pairings are perfectly correlated Gamma will be equal to one (+1 if the rankings are in the same direction; −1 of in the opposite direction). The specific P-values represent the probability that the Gamma values corresponding to each of the respective condition variables and functional limitation variable are due simply to sampling variation or ‘chance’ alone

The reported occurrence and severity of postpartum physical conditions were also consistently and, in some cases, quite strongly related to emotional well-being of the women in the study. Specifically, as we can see from the results presented in Table 5, the prevalence of depressive symptomatology, as indicated by CES-D scores was generally lower for women reporting no specific physical condition and increased if physical problems were reported to be of moderate or major rather than of minor severity. Statistically significant ordinal-level relationships, indicating greater likelihood of depressive symptomatology with condition/condition severity, were found for fatigue, headache, nausea; for backache; for vaginal pain or dyspareunia; and for urinary or bowel problems. For abdominal pain, the results tended in the same direction, but the relationship was not statistically significant. Women who reported having breast soreness of moderate or major severity and constipation of either moderate or major severity had higher prevalence of depressive symptomatology than those who did not, but again the trend was weak and did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5. Specific Postpartum Conditions, Depressive Symptomatology, and Emotional Well-being.

| --- % With Depressive Symptomatology -- | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never A Problem |

Problem of Minor Severity |

Problem of Moderate or Major Severity |

P –Value | |

| Condition | ||||

| Fatigue, Headaches, Nausea | 17.4 | 19.9 | 27.9 | 0.001 |

| Backache | 18.3 | 17.8 | 29.3 | 0.05 |

| Abdominal Pain | 20.3 | 25.8 | 26.5 | n.s. |

| Vaginal Pain or Dyspareunia | 19.2 | 25.0 | 43.6 | 0.001 |

| Constipation or Hemorrhoids | 20.4 | 20.3 | 29.6 | n.s. |

| Urinary or Bowel Problems | 19.8 | 24.4 | 32.7 | 0.001 |

| Breast Soreness | 20.8 | 17.3 | 28.3 | n.s. |

| --- % Emotional Well-being Fair or Poor -- | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never A Problem |

Problem of Minor Severity |

Problem of Moderate or Major Severity |

||

| Condition | ||||

| Fatigue, Headaches, Nausea | 9.6 | 16.7 | 33.1 | 0.001 |

| Backache | 11.8 | 20.2 | 29.6 | 0.001 |

| Abdominal Pain | 15.8 | 24.2 | 41.0 | 0.001 |

| Vaginal Pain or Dyspareunia | 15.5 | 26.7 | 44.9 | 0.001 |

| Constipation or Hemorrhoids | 16.9 | 17.7 | 30.9 | 0.03 |

| Urinary or Bowel Problems | 15.0 | 17.9 | 45.1 | 0.001 |

| Breast Soreness | 15.8 | 34.6 | 45.3 | 0.001 |

A similar, but even stronger and more consistent pattern of relationships was found for the percentage of women in relatively poor, overall emotional health (i.e., those reporting their own overall emotional health as being only “fair” or “poor”). Relatively poor emotional health was significantly related to all conditions, with increasing percentages corresponding to greater reported condition severity. Women reporting fatigue, headaches or nausea of moderate or major severity were more than three times more likely (9.6% vs. 33.1%) to also report being in relatively poor overall emotional health at the time of the survey. The direction and magnitude of this relationship were essentially the same for all other conditions, with the possible exception of “constipation or hemorrhoids” where the pattern was consistent but somewhat weaker.

In summary, our measure of functional health impairment and both measures of emotional well-being were consistently associated with postpartum physical health problems and the severity of those problems, as reported by women in the study at 9-12 months postpartum.

The consistency of these relationships across separate problem or condition categories suggests that both functional impairment and poor emotional health may be tied to a kind of cumulative effect or overall physical morbidity burden reflected by the number and severity of postpartum health problems. The data presented in Table 6 demonstrate that the presence of one or more functional limitations, depressive symptomatology, and poor overall emotional health, all occur more frequently with higher levels of the postpartum ‘morbidity burden scale’ -- as described in the methods section of this paper. Functional limitations, for example, were almost five times more prevalent among those high (43.5%), as opposed to low (9.3%), on the morbidity burden scale. Similarly, depressive symptomatology was more than twice that for those with a high (34.8%) compared to those with a low (16.1%) or no (16.8%) morbidity burden. Moreover, relatively poor overall emotional health was about six times more likely (45.7% vs. 7.6%) to be reported by respondents with a morbidity burden that was high as opposed to none.

Table 6. Postpartum Morbidity Burden, Self-reported Emotional Well-being, and Depressive Symptomatology.

| With Depressive Symptomatology N (%) |

Emotional Well-being: Fair/Poor N (%) |

With Functional Limitation N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Morbidity Burden | |||

| None | 69 (16.8) | 31 (7.6) | 38 (9.3) |

| Low | 61 (16.1) | 52 (13.7) | 69 (18.2) |

| Medium | 99 (25.0) | 89 (22.5) | 89 (22.5) |

| High | 48 (34.8) | 63 (45.7) | 60 (43.5) |

| p-Value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Morbidity Burden (Excluding Fatigue, Headache, Nausea) | |||

| None | 96 (17.2) | 48 (8.6) | 62 (11.1) |

| Low | 85 (20.5) | 78 (18.8) | 90 (21.7) |

| Medium | 66 (23.5) | 67 (23.8) | 72 (25.6) |

| High | 30 (43.5) | 42 (60.9) | 32 (46.3) |

| p-Value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Finally, because fatigue, headaches, and nausea could be regarded as relatively nonspecific complaints that could represent both psychological and physical problems (2), we recalculated the postpartum morbidity burden scale excluding these items and re-examined the relationships with depressive symptomatology, functional limitations, and overall self-reported emotional health. The pattern of results (bottom portion of Table 6) was essentially the same -- with equally strong, if not even stronger, relationships pertaining to all measures.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study of low income, inner-city women toward the end of the first year postpartum we found that reports of functional limitations, depressive symptomatolgy, and poor emotional health, were consistently associated with physical health problems. In addition, our ‘morbidity burden’ scale indicated a “dose response’ relationship between the degree of severity of the physical problem, functional impairment and emotional well-being of the postpartum women in our study.

We are unaware of any studies conducted on a U.S. community-based sample, examining these relationships. Brown and Lumely published the results of a postal survey, with a telephone follow-up component, conducted in Victoria, Australia, in an attempt to determine the relationship between maternal depressive symptomatolgy (as measured by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale or EPDS) and physical symptoms of postpartum women (37). Findings from the survey of 1,336 respondents (representing a 62% response rate) at 7-9 months postpartum were consistent with those reported here; maternal depressive symptomatolgy (EPDS ≥ 13) was significantly associated with reported back pain, urinary incontinence, bowel problems, tiredness, and “more minor colds and illnesses than usual”. In the telephone follow-up portion of the study, conducted six weeks later (n=204) maternal depression measured by the EPDS at the time of the initial survey was associated with current urinary incontinence, tiredness, and having “more colds and minor illnesses than usual”. In another study, based on telephone interviews of new mothers who delivered in one of six Toronto area hospitals (N=200; response rate 60%), Ansara et al. reported that a history of depression during pregnancy was significantly related to bad headaches and fatigue, but not to backaches, perineal pain, bowel problems or hemorrhoids, at 2-3 months postpartum (2). The prevalence and range of physical health conditions among the postpartum women that Ansara and her colleagues interviewed led them to conclude that “these more ‘typical’ maternal health outcomes have received relatively little research attention,” and that, “consequently, their pervasiveness and the cumulative effect that they have on women’s postnatal recovery may not be fully appreciated by researchers, clinicians, or even women themselves.” Moreover, they argued, “these health problems contribute to a burden of ill health and when considered in the greater context of women’s lives, they can interfere with women’s ability to adjust to new motherhood, and to resume prior work, family and social roles and responsibilities” (2, p.123).

Because of the cross-sectional nature of the study it is not possible to make any definitive statement about the direction of causality. It would seem plausible to suggest, however, that the presence of postpartum physical health problems undermines the functional health status and increases the emotional distress, including depressive symptoms, of women during the postpartum period. In fact, this is a point of view that has been offered by others (37), and it is supported by some empirical evidence suggesting that, at least in women, somatic complaints are indeed risks factor for subsequent depressive episodes (38). The findings presented here, that our morbidity burden scale remained strongly correlated with measures of poor emotional health, even after excluding those particular symptoms that are perhaps most frequently regarded as physical manifestations of emotional distress, is generally consistent with this theme. In all likelihood, however, causality is bi-directional. Indeed, results from cross-sectional studies published in the psychiatric literature have been used to strengthen the argument that depressive/anxiety disorders may amplify physical complaints, and that better detection of physical symptoms can improve the detection of such disorders among pregnant women (39), as well among the general population of adults (40) in primary care settings. In general, the extent to which somatic symptoms may contribute to depression or undermine emotional well-being (or vice versa) has largely been unexplored (38), and, as noted above, the study design limits our ability to directly address the complex issues related to the direction of causality. Additional research would appear to be warranted in order to elucidate the causal relationships between physical conditions (or ‘hidden morbidity’) and functional impairment in the postpartum period on the one hand, and postpartum depression and/or emotional distress among new mothers on the other.

Our study was limited to a sample of low-income urban women obtaining prenatal care at community health centers. Compared to the general population of childbearing women, the women in our study sample are younger and less educated; and a relatively high percentage of the population is minority, and the pregnancy outcomes are worse. Twelve percent of the sample, for example, delivered at low birthweights, compared to 8.1 percent (in 2004) for the nation as a whole. The characteristics of the sample reflect the sites for recruitment for the larger longitudinal study of which this study is a part – that is, participants for the larger study were initially enrolled at community-based health centers located in relatively poor neighborhoods throughout the city. We would expect, therefore, that the overall health status of the women in our study to be relatively poor. Perhaps, as a result, the prevalence and severity of postpartum health problems might be greater than that for childbearing women as whole. However, we see no compelling reason to suggest that the core relationships that were examined here, between physical health problems, functional status and emotional well-being would not hold for the general population of childbearing women in the U.S. Nonetheless, further research is needed to confirm the generalizability of our findings to other populations of postpartum women.

Regardless of the limitations of this study, the findings have important implications for clinical practice. First, although the maternal health outcomes examined in this study may be considered by some as ‘typical’, and perhaps of minor clinical significance, one out of every five respondents reported at least one of those conditions as having been a major problem for them, and 45% reported one or more as having been more than just a minor problem. This confirms recent findings that such problems are quite common and therefore should not be dismissed. It also highlights the need for increased attention and concern since many women appear to experience such problems as negatively affecting their quality of life. Secondly, the findings suggest a need for increasing awareness among obstetrical and other health professionals about the possibility of severe emotional distress, including depression, among postpartum women presenting with multiple or severe physical complaints. This is especially true in light of the fact that childbearing women appear to be less willing to disclose or discuss psychological problems or emotional issues than they are to discuss physical complaints -- perhaps, in part, because providers themselves may be less comfortable dealing with such topics (41). Simply stated, multiple physical complaints, or complaints of severe discomfort are likely to be associated with functional impairments, emotional distress, and even depressive states, which may not be routinely identified and treated during postpartum follow-up visits.

Conclusions

Although physical problems typically associated with the postpartum period are often regarded as transient or comparatively minor, we found that they are strongly related to both the functional impairment and poor emotional health of the women in our study sample. In brief, the evidence presented here strongly suggests that postpartum physical health problems are common, salient, and cumulative, and negatively influence the quality of life of women following parturition. In addition, the results suggest that clinical assessments which include the physical, functional, as well as emotional health status of women in the year following childbirth have a greater potential to identify the range of problems related to childbirth, and thus improve the overall quality of care available to postpartum women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ATPM TS-0626 and TS-0561, Atlanta Georgia; and The National Institute for Child Health and Human Development/RO1HD36462-01 A1

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers LL. Health problems after childbirth. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2000;45:55–7. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(99)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansara D, Cohen MM, Gallop R, Kung R, Schei B. Predictors of women’s physical health problems after childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;26:115–25. doi: 10.1080/01443610400023064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kline CR, Martin DP, Deyo RA. Health consequences of pregnancy and childbirth as perceived by women and clinicians. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:842–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loverro G, Pansini V, Greco P, Vimercati A, Parisi AM, Selvaggi L. Indications and outcome for intensive care unit admission during puerperium. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001;265:195–8. doi: 10.1007/s004040000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Martin DP, Easterling TR. Association between method of delivery and maternal rehospitalization.[see comment] JAMA. 2000;283:2411–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simoes E, Kunz S, Bosing-Schwenkglenks M, Schmahl FW. Association between method of delivery, puerperal complication rate and postpartum hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;272:43–7. doi: 10.1007/s00404-004-0692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb DA, Robbins JM. Mode of delivery and risk of postpartum rehospitalization.[comment] JAMA. 2003;289:46–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.46-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madlon-Kay DJ, DeFor TA. Maternal postpartum health care utilization and the effect of Minnesota early discharge legislation. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:307–11. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gjerdingen DK, Center B. A randomized controlled trial testing the impact of a support/work-planning intervention on first-time parents’ health, partner relationship, and work responsibilities. Behav Med. 2002;28:84–91. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gjerdingen DK, Center BA. First-time parents’ prenatal to postpartum changes in health, and the relation of postpartum health to work and partner characteristics. J Am Board Fam Practice. 2003;16:304–11. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGovern P, Dowd B, Gjerdingen D, Moscovice I, Kochevar L, Lohman W. Time off work and the postpartum health of employed women. Med Care. 1997;35:507–21. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schytt E, Lindmark G, Waldenstrom U. Physical symptoms after childbirth: prevalence and associations with self-rated health. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;112:210–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson JF, Roberts CL, Currie M, Ellwood DA. Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: associations with parity and method of birth. Birth. 2002;29:83–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gennaro S, Bloch J. Postpartum health in mothers of term and preterm infants. Journal of Women & Health. 2005;41:99–112. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung EK, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Lee HJ, Culhane JF. Maternal depressive symptoms and infant health practices among low-income women. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e523–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush AJ, et al. Children of currently depressed mothers: a STAR*D ancillary study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:126–36. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumley J, Watson L, Small R, Brown S, Mitchell C, Gunn J. PRISM (Program of Resources, Information and Support for Mothers): a community-randomised trial to reduce depression and improve women’s physical health six months after birth [ISRCTN03464021] BMC Public Health. 2006;6:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1071–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, Leventhal H. Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1442–50. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000164050.34126.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diehr PH, Derleth AM, McKenna SP, et al. Synchrony of change in depressive symptoms, health status, and quality of life in persons with clinical depression. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel BA, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: results from a longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1265–70. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Rippen N, Lowensteyn I, Khalife S. Health-related quality of life in postpartum depressed women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2006;9:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Everson-Rose SA, Skarupski KA, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF. Do depressive symptoms predict declines in physical performance in an elderly, biracial population? Psychosom Med. 2005;67:609–15. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000170334.77508.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huprich SK, Porcerelli J, Binienda J, Karana D. Functional health status and its relationship to depressive personality disorder, dysthymia, and major depression: preliminary findings. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22:168–76. doi: 10.1002/da.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culhane JF, Rauh V, McCollum KF, Hogan VK, Agnew K, Wadhwa PD. Maternal stress is associated with bacterial vaginosis in human pregnancy. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2001;5:127–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1011305300690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Culhane JF, Raugh VA, Elo IT, McCollum KF, Hogan V. Exposure to chronic stress and ethnic differences in rates of bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1272–1276. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HJ, Rubio MR, Elo IT, McCollum KF, Chung EK, Culhane JF. Factors associated with intention to breastfeed among low-income, inner-city pregnant women. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2005;9(3):253–61. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castrucci BC, Culhane JF, Chung EK, Bennett I, McCollum KF. Smoking in pregnancy: patient and provider risk reduction behavior. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(1):68–76. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200601000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung EK, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Culhane JF. Does prenatal care at community-based health centers result in infant primary care at these sites? Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett IM, Culhane JF, McCollum KF, Elo IT. Unintended rapid repeat pregnancy and low education status: any role for depression and contraceptive use? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(3):749–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett IM, Culhane JF, McCollum KF, Mathew L, Elo IT, Bennett IM, et al. Literacy and depressive symptomatology among pregnant Latinas with limited English proficiency. Am J of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(2):243–8. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okun A, Stein REK, Bauman LJ, Johnson Silver E. Content validity of the Psychiatric Symptom Index, CES-Depression Scale, and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory from the perspective of DSM-IV. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:1059–1069. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS, Locke BZ, editors. The community mental health assessment survey and the CES-D Scale. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas JL, Jones GN, Scarinci IC, Mehan DJ, Brantley PJ. The utility of the CES-D as a depression screening measure among low-income women attending primary care clinics. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31:25–40. doi: 10.2190/FUFR-PK9F-6U10-JXRK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.SPSS for Windows, Rel 15.0.0. SPSS Inc.; Chicago: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown S, Lumley J. Physical health problems after childbirth and maternal depression at six to seven months postpartum. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;107:1194–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terre L, Poston WS, Foreyt J, St Jeor ST. Do somatic complaints predict subsequent symptoms of depression? Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72:261–7. doi: 10.1159/000071897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly RH, Russo J, Katon W. Somatic complaints among women cared for in obstetrics:normal pregnancy or depressive and anxiety symptom amplification revisited? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:107–13. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barkow K, Heun R, Ustun TB, Berger M, Bermejo I, Gaebel W, Harter M, Schneider F, Stieglitz RD, Maier W. Identification of somatic and anxiety symptoms which contribute to the detection of depression in primary health care. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19:250–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Street RL, Gold WR, McDowell T. Using health status surveys in medical consultations. Med Care. 1994;32:732–44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]