Abstract

Novel 5,6-disubstituted pyridazin-3(2H)-one derivatives were designed and synthesized as combretastatin A-4 analogues. Our objective was to overcome the spontaneous cis to trans isomerization of the compound. We therefore replaced the cis-double bond with a pyridazine ring. The antiproliferative activity of the novel analogues was evaluated against four human cancer cell lines (HL-60, MDA-MB-435, SF-295 and HCT-8). We found that the analogues had little activity either against selected cell lines or against purified tubulin. Molecular modeling studies may account for their inactivity.

Keywords: Pyridazine, Combretastatin A-4, Cytotoxicity, Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling, Anticancer agent, Tubulin activity

1. INTRODUCTION

Combretastatin A-4 (CA-4; (Fig. 1), a natural product isolated from the bark of the South African bush willow tree Combretum caffrum, [1, 2] possesses high cytotoxic activity against multiple human cancer cells, including multidrug resistant cancer cell lines [3, 4]. The molecule binds at or near the colchicine site and inhibits tubulin polymerization, and this ultimately leads to cell death [5]. Moreover, combretastatin A-4 displays selective toxicity toward tumor vasculature, disrupting the blood supply to tumor cells [4].

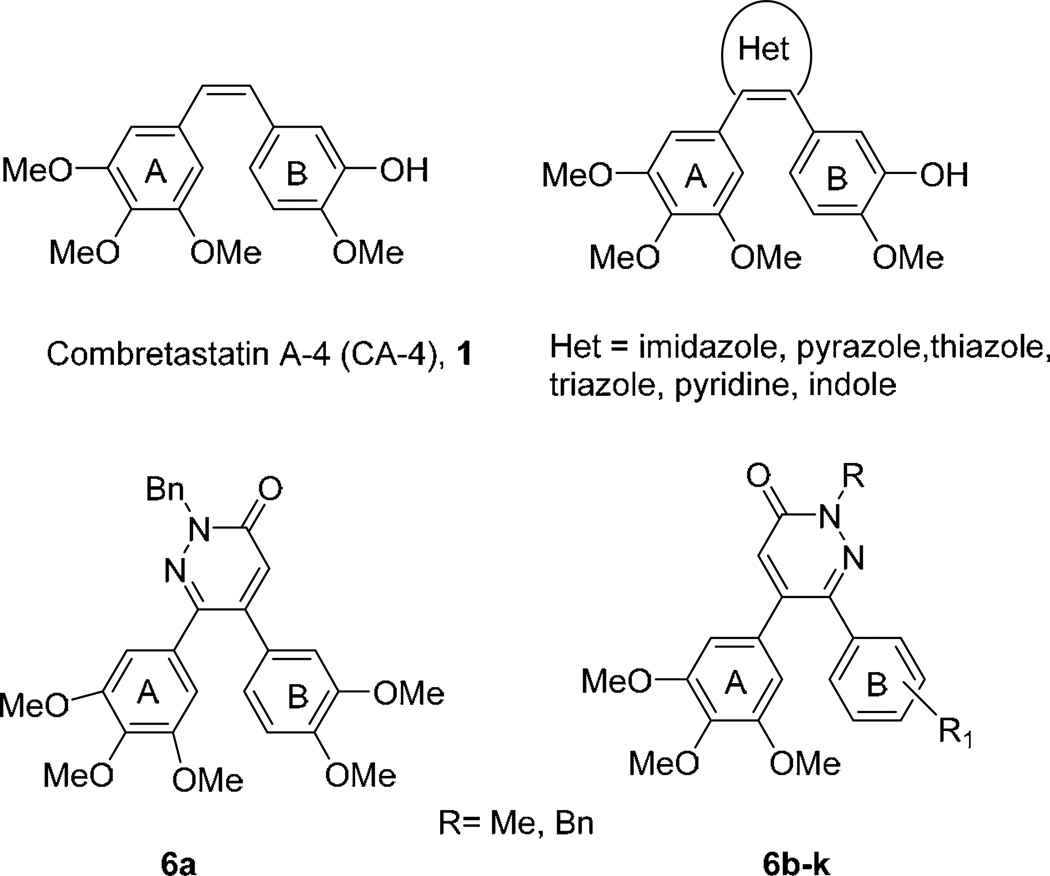

Fig. (1).

5,6-diaryl-substituted pyridazone derivatives.

Structure activity relationship (SAR) studies [6–8] showed that the cis-configuration of the double bond, bearing two aryl groups and the 3,4,5-trimethoxy substituents on ring A are essential for biological activity. However CA-4 suffers from isomerization of the double bond to the inactive trans-form (the more stable conformer) and very low water solubility. A key approach to overcome double bond isomerization of CA-4 is to replace the olefin by either a five-or a six-membered heterocyclic ring. Several analogues possessing heterocyclic ring systems such as isoxazole [9], pyridine [9], imidazole [10] or triazole [11] have been synthesized and assessed for their anti-cancer activity. For some of them, their antiproliferative and/or inhibitory effects on tubulin polymerization activity were greater than or similar to those of CA-4.

In the present work we designed and synthesized some novel CA-4 analogues. In particular, the alkenyl motif of CA-4 was incorporated in a pyridazinone ring system, yielding compounds 6 that incorporate both of the two phenyl rings A and B of the starting CA-4 at the 5 and 6 positions Fig. (1) of the pyridazinone ring.

We fixed first on position 5 a 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxyphenyl ring identical to the A ring of CA-4 and examined several substitutions on the other aryl moiety corresponding to the B ring of CA-4 (6bk). We also reconsidered the substitution pattern around the pyridazine ring by interchanging the substitution pattern of rings A and B. One regioisomer was prepared in this work (6a). The synthesis, the antiproliferative activity and inhibitory effects on tubulin polymerization of these new compounds were described.

2. CHEMISTRY

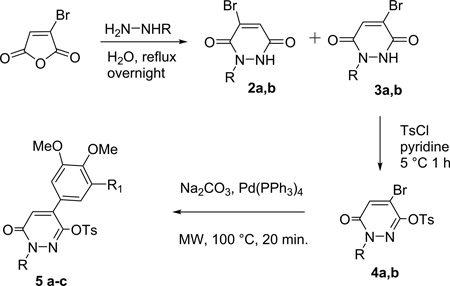

For the preparation of 6, we took advantage of an original desymmetrization method of 4-bromopyridazine-3,6-diones by means of N-alkyl substitution. The two isomeric intermediates 2 and 3 allowed regioselective control of chemical variation at different positions of the pyridazine backbone [12]. Thus, the treatment of bromomaleic anhydride with substituted hydrazines gave a mixture of the expected N-alkylpyridazine-3,6-diones 2a,b and 3a,b.

Due to their similar Rf values, the regioisomers could not be separated by column chromatography. However, a simple trituration of the crude material containing both compounds 2 and 3 with a mixture of ethyl acetate and diethyl ether (1:4) gave an insoluble residue, which was recovered and recrystallized from ethanol, giving the pure regioisomer 3a,b. The filtrate was evaporated, and the solid was recrystallized from isopropyl ether, affording the other isomer 2a,b. Activation of the free amides 3a,b with tosyl chloride in pyridine led to the corresponding O-tosyl derivatives 4a,b. Compounds 4a,b were subjected to microwave (MW) assisted Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction [12–15] with 3,4-di-OMe, or 3,4,5-tri-OMe boronic acids to give 5a–c in good yields Table 1.

Table 1.

Preparation of Compounds 2–5

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Yield (%)a |

Yield (%)a |

Yield (%) |

R1 | Yield (%) |

| 1 2 |

Bn | 2a (30) | 3a (44) | 4a (76) | H OMe |

5a (80) 5b (75) |

| 3 | Me | 2b (30) | 3b (45) | 4b (77) | OMe | 5c (70) |

Yields after recrystallization.

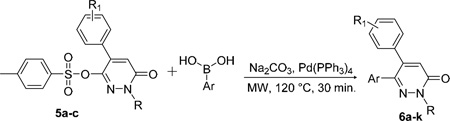

The tosyl group of 5a-c was easily replaced by aromatic systems by means of another Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction to afford the corresponding compounds 6a-k in good yields (Table 2). Such an approach was especially appealing to us, because of the large number of substituents that could be incorporated at position 6 of the pyridazine ring Table 2.

Table 2.

Preparation of Compounds 6a–k

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cpd | R | R1 | Ar | Yield (%) |

| 6a | Bn | 3.4-(OMe)2 | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 Ph | 82 (89)a |

| 6b | Bn | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 4-OMe Ph | 64 |

| 6c | Bn | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 3-OH Ph | 65 |

| 6d | Bn | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 3-NH2 Ph | 65 |

| 6e | Bn | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 3-CH2OH Ph | 71 |

| 6f | Bn | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 1H-indol-6-yl | 75 |

| 6g | Bn | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | naphthalen-2-yl | 67 |

| 6h | Me | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 4-OMe Ph | 82 |

| 6i | Me | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 3-OH Ph | 66 |

| 6j | Me | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 3-NH2 Ph | 73 |

| 6k | Me | 3,4,5-(OMe)3 | 3-CH2OH Ph | 70 |

Two successive Suzuki couplings in a one pot reaction.

However, for compound 6a, we performed two successive Suzuki couplings in a one pot procedure (see experimental part). The reaction was successful, as we obtained the expected disubstituted pyridazinone 6a in 89% yields.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The novel synthesized CA-4 analogues 6a–k were evaluated for their antiproliferative activity against the four cancer cell lines listed above, and the results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antiproliferative Activities

| Compound No |

IC50 µM* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-435 | HCT-8 | SF-295 | HL-60 | |

| 6a | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| 6b | 29 | 10.4 | 22.3 | 8.9 |

| 6c | 26.9 | 15.3 | 12.1 | 6.8 |

| 6d | >40 | >40 | >40 | 15.87 |

| 6e | 35 | 18.3 | 14.3 | 8.3 |

| 6f | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| 6h | 39.8 | >20 | 50 | 14.1 |

| 6i | >40 | 34.6 | 21.4 | 10.8 |

| 6j | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| 6k | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 |

| Combretastatin A-4 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| Doxorubicin | 1.5 | 0.13 | 0.5 | 0.05 |

All measurements were determined in triplicate, and mean values are reported. Data are presented as IC50 values, with 95% confidence intervals.

The tested compounds showed only mild to moderate antiproliferative activity against the tested cell lines. These µM IC50 values did not reach the level of potency of either doxorubicin or CA-4. Consistent with the relatively weak cytotoxicity observed, these compounds were found to have no effect on tubulin polymerization at 20 µM, in contrast to the strong inhibitory activity of CA-4 (IC50, about 1 µM). The assay we used was the glutamate-induced, GTP-dependent assembly of purified bovine brain tubulin [16].

Despite the mild activity observed with our pyridazine compounds, some SAR data and comments should be noted:

The lack of activity relative to CA-4 does not reflect steric hindrance resulting from the presence of bulky substituents like a benzyl group, as similar potencies and selectivities towards different cell lines were found with both the N-benzyl and N-methyl derivatives (compare 6b with 6h, 6c with 6i and 6e with 6k, respectively). In fact, the N-methyl derivatives were generally even less active than the N-benzyl derivatives.

The dramatic loss of activity (2–3 orders of magnitude) when compared with CA-4 probably results from a critical change in a structural feature common to both series of compounds. The presence of a carbonyl dipole in the pyridazinone ring is probably not detrimental, as similar compounds with a triazole [11] or an oxadiazole [6] ring had strong anti-proliferative activities.

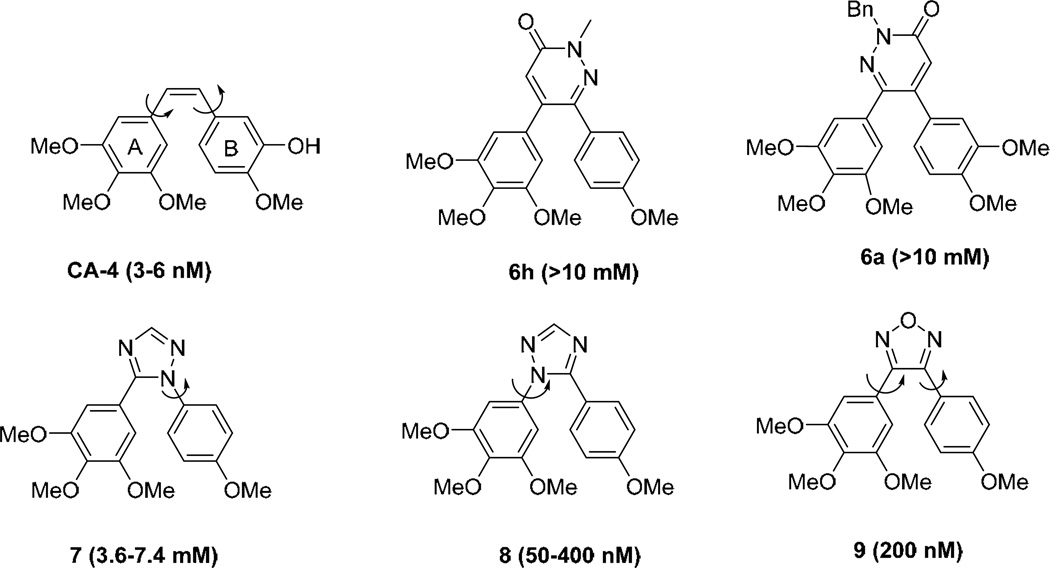

If we consider the major role played by both aromatic rings A and B in CA-4, specific conformations allowing optimal locations of m-OMe groups as H bond donor systems should be considered as critical. A recent publication presented an interesting series of triazole-derived CA-4 structural analog [11]. Two representatives 7 and 8 are shown in Fig. (2). Whereas compound 7 had low potencies similar to those found with our compounds, compound 8 had potent antiproliferative activity (IC50’s ranging from 50 to 400 nM in different cancer cell lines). Compound 8 was about 10 times less potent than CA-4.

Fig. (2).

Conformational behaviors of CA-4 and other structurally related compounds.

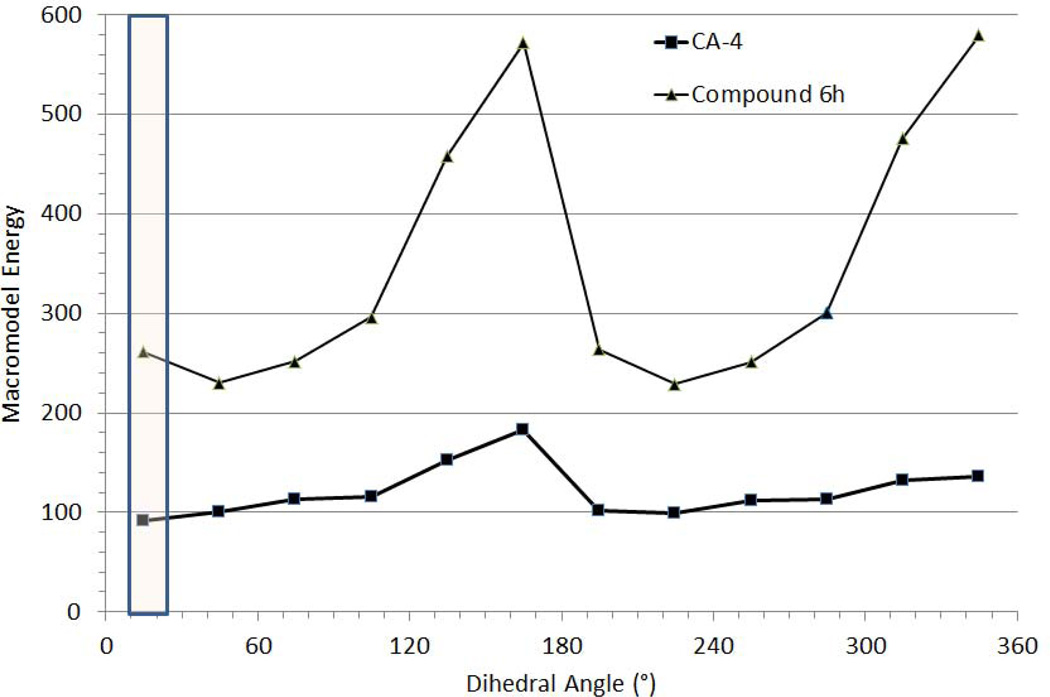

As depicted in Fig. (3), modeling studies showed that the rotation about ring A (trimethoxybenzene ring) is more unfavorable for compound 6h than for CA-4, as supported by two high energy barriers in a 360° rotation about ring A. Additionally, whereas the torsional bond angle of CA-4 that maps the bioactive conformation of colchicine [17] represents a minimum in the energy profile, a similar torsional bond angle for 6h is not located at a minima but is proximal to a minimum. These two factors suggest that 6h and its congeners are restricted in their ability to assume a bioactive conformation in the colchicine site. Thus, the desired conformational restriction appears to limit the activity of our compounds.

Fig. (3).

Energy profile of conformations of CA-4 and 6h derived from 30° torsional bond changes in ring A (trimethoxybenzene ring). The highlighted, boxed area shows the region of the torsional bond angles that is most consistent with that in the bioactive conformation of colchicine.

Major methoxy groups from both rings A and B are probably involved in a set of H bond interactions. In addition, electron-rich ring systems may interact in π-π interactions, and, finally, an active conformation may need specific rotamers from one or both aromatic rings. It is important to note that the location of para methoxy groups is not dependent upon rotation of both ring systems, whereas the meta methoxy groups may need free rotation of ring A to adopt the best position for H bonding. Fig. (3) clearly illustrates a strong difference between rotational features of ring A in CA-4 and the inactive pyridazinone 6h. The CA-4 ring A is relatively free to rotate, as the result of an expected similar free rotation of ring B. On the other hand, the ring A in compound 6h may allow strong delocalization of electrons of the para methoxy group toward the carbonyl amide (cinnamamide structure). A similar feature may be found in the structure of 7 and account for its inactivity. This partial delocalization of π electrons may lead to restriction of rotation and need higher energy levels to reach an active conformation. Free rotation of ring A is more or less restored when ring A is attached to an sp3 carbon [9] or to a trigonal nitrogen in compound 8 or to an sp2 carbon imine in compound 9. In keeping with these observations, compound 6a should be more active than 6h, with a lower µM range of IC50 antiproliferative values (see pyridine derivatives [9]). However, inactivity of 6a may result specifically from the presence of a bulky benzyl group that would bind in a region of the protein binding site sensitive to steric hindrance.

This SAR analysis highlights novel conformational hypotheses dealing with the active conformation of CA-4. The cis-geometry with both aromatic rings in close proximity must be associated with at least one freely rotating ring system, preferentially ring A, to obtain compounds with significant activities. This hypothesis is supported by i) the relative inactivity of our compounds (IC50’s ≥ 10 µM) when compared with CA-4, as both 6a and 6h present possible electronic delocalization with resulting restricted flexibility, and ii) conformational features observed in the crystal structure of another N-3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl triazole derivative, which showed potent CA-4 mimetic properties [18].

4. CONCLUSION

The novel CA-4 analogues 6a-k were designed and synthesized in good yield using Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling. These cis-restricted analogues overcome the isomerization problem of CA-4. Antiproliferative evaluation, however, showed that 6c and 6e have only modest activity against the cell lines examined (HL-60, MDA-MB-435, SF-295 and HCT-8). The novel hypothesis we present here emphasizes the presence of a free rotating ring A system and will serve as a more efficient guide for the future design of novel combretastatin structural analogues with improved ADMET properties.

5. EXPERIMENTAL PART

5.1. Chemistry

All materials purchased from commercial suppliers were used as received. Purification was done by Armen spot flash chromatography using silica gel Merck 60 (particle size 0.040–0.063 mm). Purity was determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Dionex U3000) using the following procedure: the compounds were dissolved at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL in MeOH. Then 5 µL of the sample was injected into an HPLC column (Acclaim 120, C18, 3 µm, 120 Å, 4.6 × 100 mm). Elution was performed with a gradient of water (containing 0.05% TFA):MeOH from 70:30 to 0:100 for 10 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, starting the gradient after 1.3 min. UV absorption was monitored from 190 to 400 nm using a diode array detector. Purity of the compounds was determined at 202, 210 and 254 nm. The melting points reported are uncorrected. IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Fisher Nicolet380 ATR FT-IR [13]. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 spectrometer operating at 100 MHz. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 300 MHz Avance DPX, dual probe. Chemical shifts are given in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS), coupling constants J are given in Hertz. Mass spectra were determined by ESI–mass spectra obtained on an LC/MS instrument (AGILENT, MS: MSD-SL, LC: 1200SL). For MW reactions, irradiation was performed using a Biotage Initiator EXP. Compounds 2a, 3a and 4a were prepared according to a reported procedure [12].

General Procedure for the Preparation of N-alkyl-pyridazine- 3,6-diones 2 and 3

In a 100 mL round bottom flask, alkyl hydrazine sulfate (16.95 mmol) was dissolved in boiling water (40 mL). To this solution bromomaleic anhydride (16.95 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was heated under reflux overnight and then cooled to room temperature. The resulting solid was collected by filtration and dried to yield the corresponding crude N-alkyl-pyridazine-3,6-diones 2 and 3. The crude product 2 and 3 was separated by trituration with an AcOEt/ethyl ether 1:4 mixture, with 2 going into solution, leaving 3 as a solid. After 2 was removed by filtration, crystallization from ethanol yielded isomer 3. Evaporation of the mother liquor under reduced pressure led to 2, which was crystallized from isopropyl ether.

1-Benzyl-5-bromo-1,2-dihydropyridazine-3,6-dione (2a)

White solid (30%); mp 157–159 °C; 1H NMR in agreement with previous data.

1-Benzyl-4-bromo-1,2-dihydropyridazine-3,6-dione (3a)

White solid (44%); mp 244–246 °C; 1H NMR in agreement with previous data.

5-Bromo-1-methyl-1,2-dihydropyridazine-3,6-dione (2b)

White solid (30%); mp 194–196 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 11.31 (s, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 3.53 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 155.2, 151.5, 129.8, 128.6, 39.9

4-Bromo-1-methyl-1,2-dihydropyridazine-3,6-dione (3b)

White solid (45%); mp 276–277 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 12.00 (s, 1H), 7.42 (s, 1H), 3.44 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 162.4, 154.5, 139.2, 128.2, 43.4

General Procedure for O-tosylation 4a and 4b

Tosyl chloride (4.5 mmol) was added to a solution of pyridazine 3,6-dione 3a or 3b (4.5 mmol) in pyridine (6 mL) under argon at 5 °C and stirred for 1 h. The solvent was evaporated under vacuum, and the residue was diluted with AcOEt (25 mL), washed with a saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution (2 × 25 mL) and brine. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure to yield a pure compound.

1-Benzyl-4-bromo-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyridazin-3-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (4a)

Yellow solid (76%); mp 97–98 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 7.79 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.35–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.14–7.11 (m, 2H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 2.43 (s, 3H).

4-Bromo-1-methyl-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyridazin-3-yl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (4b)

Yellow solid (77%); mp 157–158 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 3.59 (s, 3H), 2.50 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 158.4, 146.3, 142.9, 134.4, 133.0, 129.9, 128.9, 125.0, 39.7, 21.8.

General Procedure for Synthesis of Compounds 5a-c

Pyridazine derivative 4a or 4b (0.230 mmol), sodium carbonate (0.517 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (9.19 µmol) and the appropriate boronic acid drivative (0.253 mmol) in a 3:1 mixture of DME (dimethoxyethane)/H2O (4 mL) were mixed in a 5 mL process vial, which was flushed with argon for 2 min. The reaction mixture was then capped tightly and heated in a MW apparatus at 100 °C for 20 min. The mixture was cooled and the solvent evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in AcOEt (20 mL), and the organic layer was washed with H2O (3 × 20 mL) and brine. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude solid product was purified by flash chromatography; the eluting solution used is indicated for each specific compound.

1-Benzyl-4-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyridazin-3-yl-4-methylbenzene Sulfonate (5a)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/1); oil (80%); IR (cm−1): υ 3062 (C-H aromatic), 2925 (C-H aliphatic), 1664 (C=O amide),1384, 1122 (SO2); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.56 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (br s, 5H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (dd, J = 2, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 5.16 (s, 2H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 2.44 (s, 3H); 13C NMR: δ 159.7, 150.8, 149.0, 145.6, 144.2, 141.0, 135.6, 133.5, 129.7, 129.6, 128.8, 128.6, 128.5, 128.1, 124.0, 121.9, 111.7, 111.1, 56.0, 56.0, 54.5, 21.7.

1-Benzyl-6-oxo-4-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1,6-dihydropyridazin- 3-yl-4-methyl Benzenesulfonate (5b)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/1); white solid (75%); mp 105–106 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3042 (C-H aromatic), 2937 (C-H aliphatic), 1665 (C=O amide),1382, 1124 (SO2);1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.60 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (br s, 5H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.65 (s, 2H), 5.17 (s, 2H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3,84 (s, 6H), 2.44 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.6, 153.3, 145.7, 144.0, 141.1, 139.7, 135.5, 133.4, 130.2, 129.6, 128.8, 128.6, 128.5, 128.2, 126.7, 106.1, 61.0, 56.2, 54.7, 21.7; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 7.1 min.

1-Methyl-6-oxo-4-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1,6-dihydropyridazin- 3-yl-4-methyl Benzenesulfonate (5c)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/2); white solid (70%); mp 170–172 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3012 (C-H aromatic), 2945 (C-H aliphatic), 1666 (C=O amide),1383, 1126 (SO2);1H NMR (CDCl3): υ 7.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.28 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.63 (s, 2H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 6H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 2.46 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 160.1, 153.3, 145.9, 143.7, 141.2, 139.7, 133.2, 129.7, 129.6, 128.5, 126.7, 106.1, 61.0, 56.2, 39.6, 21.7; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 6.24 min.

General Procedure for Synthesis of Compounds 6a-k

A suspension of pyridazine derivative 5a–c (0.162 mmol), sodium carbonate (0.487 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (9.76 µmol) and the appropriate boronic acid derivative (0.227 mmol) in a 3:1 mixture of DME/H2O (3.33 mL) were mixed in a 5 mL process vial, which was flushed with argon for 2 min. The reaction mixture was then capped tightly and heated in a MW apparatus at 120 °C for 30 min. The mixture was cooled and the solvent evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in AcOEt (20 mL), and the organic layer was washed with H2O (3 × 20 mL) and brine. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude solid product was purified by flash chromatography; the eluting solution used is indicated for each specific compound.

One Pot Procedure for the Synthesis of Compound 6a

A suspension of pyridazine derivative 4a (100 mg, 0.230 mmol), sodium carbonate (44 mg, 0.41 mmol), 3,4-dimethoxyboronic acid (44 mg, 0.241 mmol), Pd(PPh3)4 (13,5 mg, 11.5 µmol) in a 3:1 mixture of DME/H2O (4 mL) were mixed in a 5 mL process vial, which was flushed with argon for 2 min. The reaction mixture was then capped tightly and heated in a MW apparatus at 100 °C. Progress of the reaction was monitored by HPLC. After 20 min, the mixture was cooled under argon, and the 3,4,5-trimethoxy boronic acid was added (51 mg, 0.241 mmol), followed by sodium carbonate (44 mg, 0.41 mmol). The reaction mixture was then tightly recapped and heated in a MW apparatus at 120 °C for 30 min. The mixture was cooled, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in AcOEt (20 mL), and the organic layer was washed with H2O (3 × 20 mL) and brine. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The crude solid product was purified by flash chromatography using heptane/AcOEt (1/1) to afford 6a in 89% yield.

2-Benzyl-5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) pyridazin-3(2H)-one (6a)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/1); oil (82%); IR (cm−1): υ 3062 (C-H aromatic), 2933 (C-H aliphatic), 1658 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.31 (m, 3H), 6.95 (s, 1H), 6.83–6.74 (m, 2H), 6.54 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 6.40 (s, 2H), 5.44 (s, 2H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.64 (s, 6H), 3.63 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.9, 152.8, 149.8, 148.7, 145.8, 145.1, 138.3, 136.1, 130.8, 129.1, 128.6, 128.4, 128.0, 121.5, 112.0, 111.0, 106.8, 60.9, 56.0, 56.0, 55.8, 55.1; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 7.72 min; LC/MS m/z: 489 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C28H28N2O6: C, 68.84; H, 5.78; N, 5.73. Found: C, 68.75; H, 5.71; N, 5.52.

2-Benzyl-6-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) pyridazin-3(2H)-one (6b)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/1); white solid (64%); mp 144–145 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3012 (C-H aromatic), 2942 (C-H aliphatic), 1655 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.55 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.8 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.29 (s, 2H), 5.43 (s, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.64 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.9, 153.1, 145.9, 145.3, 138.6, 136.4, 131.5, 131.2, 130.5, 129.0, 128.6, 128.5, 128.0, 127.9, 113.5, 106.3, 61.0, 56.0, 55.4, 55.2; HPLC: purity: >98%, ret. time: 7.16 min; LC/MS m/z: 459 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C27H26N2O5: C, 70.73; H, 5.72; N, 6.11. Found: C, 70.90; H, 5.59; N, 6.03.

2-Benzyl-6-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) pyridazin-3(2H)-one (6c)

Purification using DCM/AcOEt (2/1); white solid (65%); mp 198–199 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3281 (OH, broad band), 3028 (C-H aromatic), 2939 (C-H aliphatic), 1649 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.53 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 2H), 7.37–7.29 (m, 3H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (s, 1H), 6.84–6.77 (m, 2H), 6.69 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.29 (s, 2H), 5.42 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.62 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 160.1, 155.9, 153.0, 146.1, 145.5, 138.8, 137.0, 136.1, 130.6, 129.3, 129.0, 128.6, 128.2, 128.0, 121.6, 116.2, 115.7, 106.3, 61.0, 56.0, 55.4; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 6.56 min; LC/MS m/z: 445 [M+H+], 443 [M−H+], Anal. Calcd. for C26H24N2O5: C, 70.26; H, 5.44; N, 6.30. Found: C, 70.45; H, 5.59; N, 6.48.

6-(3-Aminophenyl)-2-benzyl-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)pyridazin- 3(2H)-one (6d)

Purification using DCM/AcOEt (2/1); yellow solid (65%); mp 189–191 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3457 (NH2, asymmetric), 3362 (NH2, symmetric), 3021 (C-H aromatic), 2928 (C-H aliphatic), 1652 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.54 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.04 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.66–6.51 (m, 3H), 6.32 (s, 2H), 5.43 (s, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.64 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.9, 152.9, 146.3, 146.2, 145.3, 138.7, 136.7, 136.3, 130.9, 129.0, 128.9, 128.6, 128.2, 127.9, 119.7, 115.7, 115.2, 106.3, 61.0, 56.1, 55.3; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 5.6 min; LC/MS m/z: 444 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C26H25N3O4: C, 70.41; H, 5.68; N, 9.47. Found: C, 70.32; H, 5.73; N, 9.24.

2-Benzyl-6-(3-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) pyridazin-3(2H)-one (6e)

Purification using DCM/AcOEt (2/1); white solid (71%); mp 111–113 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3558 (OH, broad), 3040 (C-H aromatic), 2942 (C-H aliphatic), 1651 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.54 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.29 (m, 5H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 6.27 (s, 2H), 5.44 (s, 2H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.61 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.9, 153.0, 146.0, 145.3, 141.0, 138.8, 136.2, 135.9, 130.8, 129.0, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 128.0, 127.7, 127.0, 106.4, 64.9, 61.0, 56.0, 55.3; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 6.44 min; LC/MS m/z: 459 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C27H26N2O5: C, 70.73; H, 5.72; N, 6.11. Found: C, 70.51; H, 5.66; N, 6.19.

2-Benzyl-6-(1H-indol-6-yl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)pyridazin- 3(2H)-one (6f)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/1); brownish solid (75%); mp 189–190 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3358 (NH), 3034 (C-H aromatic), 2937 (C-H aliphatic), 1646 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.25 (s, 1H), 7.57–7.51 (m, 3H), 7.39–7.31 (m, 3H), 7.23–7.21 (m, 2H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.95 (dd, J = 1.6, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.52–6.51 (m, 1H), 6.29 (s, 2H), 5.45 (s, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.50 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 160.0, 152.9, 147.2, 145.6, 138.5, 136.4, 135.3, 131.3, 129.3, 129.0, 128.6, 128.3, 128.1, 127.9, 125.6, 121.2, 120.3, 112.1, 106.4, 102.6, 60.9, 55.9, 55.2; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 7.04 min; LC/MS m/z: 468 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C28H25N3O4: C, 71.93; H, 5.39; N, 8.99. Found: C, 72.21; H, 5.47; N, 9.16.

2-Benzyl-6-(naphthalen-2-yl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)pyridazin- 3(2H)-one (6g)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/1); oil (67%); IR (cm−1): υ 3062 (C-H aromatic), 2932 (C-H aliphatic), 1658 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.82–7.57 (m, 5H), 7.51-7.47 (m, 2H), 7.39-7.33 (m, 4H), 7.21 (dd, J = 1.9, 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 6.31 (s, 2H), 5.48 (s, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.49 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 159.9, 153.1, 146.0, 145.4, 136.3, 133.0, 132.9, 132.8, 130.9, 129.1, 128.8, 128.6, 128.5, 128.3, 128.0, 127.6, 127.5, 126.8, 126.5, 126.5, 106.4, 61.0, 56.0, 55.3; HPLC: Purity: >95%, ret. time: 7.65 min; LC/MS m/z: 479 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C30H26N2O4: C, 75.30; H, 5.48; N, 5.85. Found: C, 75.55; H, 5.39; N, 5.70.

6-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) pyridazin-3(2H)-one (6h)

Purification using heptane/AcOEt (1/2); white solid (82%); mp 161–163 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3005 (C-H aromatic), 2939 (C-H aliphatic), 1662 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.15 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (s, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.31 (s, 2H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.64 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 160.4, 159.9, 153.1, 145.8, 145.4, 138.6, 131.1, 130.4, 128.0, 127.9, 113.6, 106.3, 61.0, 56.0, 55.4, 40.0; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 6.16 min; LC/MS m/z: 383 [M+H+]; Anal. Calcd. for C21H22N2O5: C, 65.96; H, 5.80; N, 7.33, Found: C, 65.62; H, 5.76; N, 7.40.

6-(3-Hydroxyphenyl)-2-methyl-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) pyridazin-3(2H)-one (6i)

Purification using DCM/AcOEt (2/1); white solid (66%); mp 219–220 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3296 (OH, broad), 3053 (C-H aromatic), 2937 (C-H aliphatic), 1650 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.14 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.87–6.70 (m, 3H), 6.31 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.62 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 160.7, 156.3, 153.0, 146.4, 145.7, 138.8, 136.9, 130.5, 129.5, 127.6, 121.2, 116.1, 115.8, 106.3, 61.0, 56.0, 40.2; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 5.38 min; LC/MS m/z: 369 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C20H20N2O5: C, 65.21; H, 5.47; N, 7.60. Found: C, 65.57; H, 5.72; N, 7.49.

6-(3-Aminophenyl)-2-methyl-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)pyridazin- 3(2H)-one (6j)

Purification using DCM/AcOEt (2/1); green solid (73%); mp 195–196 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3452, 3355 (NH2), 3002 (C-H aromatic), 2941 (C-H aliphatic), 1654 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.05 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 6.68–6.54 (m, 3H), 6.34 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.65 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 160.5, 153.0, 146.3, 146.0, 145.4, 138.7, 136.7, 130.8, 129.1, 127.7, 119.8, 115.7, 115.4, 106.4, 61.0, 56.1, 40.0; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 4.09 min; LC/MS m/z: 368 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C20H21N3O4: C, 65.38; H, 5.76; N, 11.44. Found: C, 65.63; H, 5.85; N, 11.74.

6-(3-(Hydroxymethyl)phenyl)-2-methyl-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl) pyridazin-3(2H)-one (6k)

Purification using DCM/AcOEt (2/1); white solid (70%); mp 119–121 °C; IR (cm−1): υ 3420 (OH, broad), 3005 (C-H aromatic), 2941 (C-H aliphatic), 1646 (C=O amide); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.34–7.24 (m, 3H), 7.09 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (s, 1H), 6.28 (s, 2H), 4.64 (s, 2H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.61 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 160.4, 153.1, 145.9, 145.4, 141.2, 138.8, 135.9, 130.8, 128.4, 128.4, 127.8, 127.5, 127.0, 106.5, 64.8, 61.0, 56.1, 40.1; HPLC: purity: >99%, ret. time: 5.24 min; LC/MS m/z: 383 [M+H+], Anal. Calcd. for C21H22N2O5: C, 65.96; H, 5.80; N, 7.33. Found: C, 65.87; H, 5.97; N, 7.22.

Antiproliferative Assay

Antiproliferative activity was tested against HL-60 (leukemia), MDA-MB-435 (melanoma), SF-295 (brain), and HCT-8 (colon) human cancer cell lines, all obtained from the National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD, USA. Cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100µg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The tested compounds were dissolved in sterile DMSO.

Antiproliferative activity against HL-60, MDA-MB-435, SF-295 and HCT-8 cells were determined using an MTT assay. In brief, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a concentration of 5×104−105 cells/well. After 24 h, the compounds (5-0.000001 µg/mL) were added to the wells (using the HTS—high-throughput screening- Biomek 3000; Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA), and the cells were incubated for 72 h. At the end of the incubation, the plates were centrifuged, and the medium was replaced by fresh medium (150 µL) containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT. Three hours later, the formazan product was dissolved in 150 µL DMSO, and the absorbance was measured using a multiplate reader at 595 nm (DTX 880 Multimode Detector, Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA).

Tubulin Polymerization Assay

The assay has been described in detail previously.16 In brief, 10 µM (1.0 mg/mL) bovine brain tubulin was preincubated for 15 min at 30 °C with 20 µM of each compound dissolved in DMSO or with varying concentrations of CA-4, so that the final concentration of the solvent was 4% (v/v) in both the control and samples containing the compounds. In addition, the 0.24 mL reaction mixtures contained 0.8 M monosodium glutamate (taken from a 2.0 M solution adjusted to pH 6.6 with concentrated HCl), with all concentrations referring to the final reaction volume of 0.25 mL. After the preincubation, the samples were placed on ice, and 10 µL of 10 mM GTP (final concentration, 0.4 mM) was added to each sample. The samples were then transferred to cuvettes maintained at 0 °C in Beckman model DU-7400 and DU-7500 spectrophotometers equipped with electronic temperature controllers. After baselines at 350 nm were established, the temperature was jumped to 30 °C, with the temperature transition taking about 1 min, and turbidity development was followed for 20 min. With an active compound, such as CA-4, the IC50 is defined as the concentration inhibiting 50% of the increase in turbidity after 20 min at 30 °C.

Molecular Modeling

The modeling software Maestro 9 (Schrodinger, LLC) was used in this investigation. Using the bioactive conformation of colchicine as the template, the initial conformations of CA-4 and compound 6h were modeled. Conformations were generated by 30° bond rotation about ring A. The conformations of CA-4 and 6h were energy minimized using 500 steps of Polak-Ribière conjugate gradient in an OPLS2005 force-field with the heavy atoms outside of the trimethoxy moiety fixed in Cartesian space. Macromodel was used to calculate the energy of each conformation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are thankful to Dr. Hussein Elkashef.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pettit GR, Singh SB, Niven ML, Hamel E, Schmidt JM. Isolation, structure, and synthesis of combretastatins A-1 and B-1, potent new inhibitors of microtubule assembly, from Combretum caffrum. J. Nat. Prod. 1987;50:119–131. doi: 10.1021/np50049a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh R, Kaur H. Advances in synthetic approaches for the preparation of combretastatin-based anti-cancer agents. Synthesis. 2009;15:2471–2491. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babu B, Lee M, Lee L, Strobel R, Brockway O, Nickols A, Sjoholm R, Tzou S, Chavda S, Desta D, Fraley G, Siegfried A, Pennington W, Hartley RM, Westbrook C, Mooberry SL, Kiakos K, Hartley JA, Lee M. Acetyl analogs of combretastatin A-4: Synthesis and biological studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:2359–2367. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liou J, Chang Y, Kuo F, Chang C, Tseng H, Wang C, Yang Y, Chang J, Lee S, Hsieh H. Concise synthesis and structure-activity relationships of combretastatin A-4 analogues 1-aroylindoles and 3-aroylindoles, as novel classes of potent antitubulin agents. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:4247–4257. doi: 10.1021/jm049802l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tozer GM, Prise VE, Wilson J, Locke RJ, Vojnovic B, Stratford MR, Dennis MF, Chaplin DJ. Combretastatin A-4 phosphate as a tumor vascular-targeting agent: early effects in tumors and normal tissues. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1626–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tron GC, Pagliai F, Grosso ED, Genazzani AA, Sorba G. Synthesis and cytotoxic evaluation of combretafurazans. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:3260–3268. doi: 10.1021/jm049096o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorion M, Agouridas V, Couture A, Deniau E, Grandclaudon P. Synthesis and cytotoxic evaluation of cis-locked and constrained analogues of combretastatin and combretastatin A4. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:5146–5149. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinney KG, Mejia MP, Villalobos VM, Rosenquist BE, Pettit GR, Verdier-Pinard P, Hamel E. Synthesis and biological evaluation of aryl azide derivatives of combretastatin A-4 as molecular probes for tubulin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000;8:2417–2425. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simoni D, Grisolia G, Giannini G, Roberti M, Rondanin R, Piccagli L, Baruchello R, Rossi M, Romagnoli R, Invidiata FP, Grimaudo S, Jung MK, Hamel E, Gebbia N, Crosta L, Abbadessa V, Di Cristina A, Dusonchet L, Meli M, Tolomeo M. Heterocyclic and phenyl double-bond-locked combretastatin analogues possessing potent apoptosis -inducing activity in HL-60 and MDR cell lines. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:723–736. doi: 10.1021/jm049622b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellina F, Cauteruccio S, Di Fiore A, Rossi R. Regioselective synthesis of 4,5-diary-l-methyl-1 H-imidazoles including highly cytotoxic derivatives by Pd-catalyzed direct c-5 arylation of 1-methyl-1H-imidazole with aryl bromides. Eur J. Org. Chem. 2008;32:5436–5445. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romagnoli R, Baraldi PG, Cruz-Lopez O, Cara CL, Carrion MD, Brancale A, Hamel E, Chen L, Bortolozzi R, Basso G, Viola G. Synthesis and antitumor activity of 1,5-disubstituted 1,2,4-triazoles as cis-restricted combretastatin analogues. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:4248–4258. doi: 10.1021/jm100245q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Araujo-Junior JX, Schmitt M, Antheaume C, Bourguignon JJ. Synthesis of regiospecifically polysubstituted pyridazinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:7817–7820. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmitt M, de Araujo-Junior JX, Oumouch S, Bourguignon JJ. Use of 4-bromopyridazine-3,6-dione for building 3-aminopyridazine libraries. Mol. Divers. 2006;10:429–434. doi: 10.1007/s11030-006-9020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nara S, Martinez J, Wermuth C, Parrot I. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions on pyridazine moieties. SYNLETT. 2006;19:3185–3204. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villemin D, Jullien A, Bar N. Isonitriles as efficient ligands in Suzuki-Miyaura reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:4191–4193. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamel E. Evaluation of antimitotic agents by quantitative comparisons of their effects on the polymerization of purified tubulin. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2003;38:1–22. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravelli RGB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature. 2004:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Peng Y, Wang XI, Keenan SM, Arora S, Welsh WJ. Highly potent triazole-based tubulin polymerization inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:749–754. doi: 10.1021/jm061142s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]