These days, more and more scientists are diving into genome sequencing projects, urged by fast and cheap next‐generation sequencing technologies. Only to discover that they are quickly drowning in an unfathomable sea of sequence data and gasping for help from experts to make biological sense of this ensuing disaster. Bioinformaticians and genome annotators to the rescue!

Microbial genome annotation involves primarily identifying the genes (or actually the open reading frames: ORFs) encrypted in the DNA sequence and deducing functionality of the encoded protein and RNA products (Fig. 1). First, a gene finder such as Glimmer (Delcher et al., 1999) or GeneMark (Lukashin and Borodovsky, 1998) is applied to the genome DNA sequence, producing a set of predicted protein‐coding genes. These programs are quite accurate, though not perfect. The next step is to take the set of predictions and search for hits against one or more protein and/or protein domain databases using blast (Altschul et al., 1997), HMMer (Eddy, 1998) or other programs. For each gene that has a significant match, the blast output together with the annotation of the hit can be used to assign a name and function to the protein. The accuracy of this step depends not only on the annotation software, but also on the quality of the annotations already in the reference database.

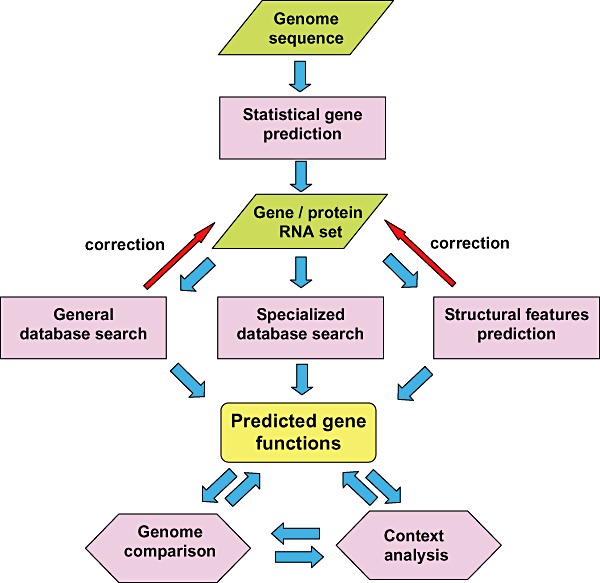

Figure 1.

A generalised flow chart of genome annotation. Statistical gene prediction: use of methods like GeneMark or Glimmer to predict protein‐coding genes. General database search: searching sequence databases (typically, NCBI NR) for sequence similarity, usually using blast. Specialized database search: searching domain databases (such as Pfam, SMART and CDD), for conserved domains, genome‐oriented databases (such as COGs), for identification of orthologous relationship and refined functional prediction, metabolic databases (such as KEGG) for metabolic pathway reconstruction and other database searches. Prediction of structural features: prediction of signal peptide, transmembrane segments, coiled domain and other features in putative protein functions.

Genome sequences deposited in NCBI/GenBank, EMBL and DDBJ databases (which mirror each other) are annotated by the submitting groups, who each use their own methods, criteria and thoroughness. This leads to a large diversity in annotation completeness and accuracy. Many of the first genomes published had very limited or no functional annotation, simply because there was very little genomic information in these reference databases to compare with. Most public genome annotation remains static for years, and many annotations have never been changed since their initial publication. Over the years, annotation updates may have been maintained by the submitters, but they are generally only stored in local databases such as GenProtEC/EcoGene for Escherichia coli K12 (Rudd, 2000), Genolist/Bactilist for Bacillus subtilis 168 (Lechat et al., 2008) and SGD for Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Christie et al., 2004).

Since gene functional annotation relies heavily on sequence similarity searching techniques with protein sequence databases, automatically annotated entries based on blast hits to NCBI databases can quickly become outdated. In the mean time, downstream sciences, such as comparative genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics and metabolomics, have rapidly increased our knowledge of many gene products. It is critical therefore, that genome annotations are frequently updated if the information they contain is to remain accurate, relevant and useful.

Re‐annotation

Re‐annotation is defined as the process of updating a previously annotated genome. Automated annotation pipelines combine many different algorithms for gene calling and protein function analysis. In some cases this is followed by manual expert curation, albeit less and less these days, which involves including experimental evidence, and using more sophisticated bioinformatics analysis, such as operon predictions, comparative genome analysis, regulatory motifs prediction, metabolic pathway reconstruction and a lot of common (biochemical) sense. Automated methods save time and resources, but will not incorporate the maximum information available from expert curators, leading to incomplete or even false designations. By contrast, manual annotation is costly and time‐consuming. However, manual re‐annotation of genomes can significantly reduce the propagation of annotation errors and thus reduce the time spent on flawed research. Hence, there is a need for a research community‐wide review and regular update of genome interpretations.

Re‐annotations can be published in literature or made available on websites. Examples of published re‐annotated genomes are unfortunately rare compared with the rapidly increasing number of sequenced genomes. A first overview of re‐annotated genomes was made by (Ouzounis and Karp, 2002). In Table 1 we list some more recently re‐annotated microbial genomes. In the latest cases, next‐generation technologies have been used for re‐sequencing of the original strain prior to re‐annotation. Exemplary is the re‐sequencing and re‐annotation of B. subtilis 168 (Barbe et al., 2009), published 12 years after the original genome paper (Kunst et al., 1997). About 2000 sequence differences were revealed, mainly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), allowing correction of some frameshifts and variation of amino acid residues prior to re‐annotation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selection of re‐annotated microbial genomes.

| Genome | Re‐sequencing | Deleted genes | New genes | Corrected genesb | Original publication | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotes | ||||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | No | 370 | 3 | 46 | 1996 | Wood et al. (2001) |

| Aspergillus nidulans | No | 640 | 494 | 2005 | Wortman et al. (2009) | |

| Prokaryotes | ||||||

| Bacillus subtilis 168 | 454 pyro, Solexa | 171a | 326 | 1997 | Barbe et al. (2009) | |

| Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168 | No | 2000 | Gundogdu et al. (2007) | |||

| Escherichia coli CFT073 | No | 608 | 299 | 435 | 2002 | Luo et al. (2009) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | No | 10 | 82 | 60 | 1998 | Camus et al. (2002) |

| Zymomonas mobilis ZM4 | 454 pyro | 271 | 48a | 539 | 2005 | Yang et al. (2009) |

Includes new pseudogenes.

Includes corrected pseudogenes, but not genes with SNPs leading to only amino acid changes.

Standardized (re)‐annotation databases

Many (re)annotation databases exist (see Table 2 for an overview), of which a few are general: DDBJ, EMBL, Pedant and NCBI GenBank. The ERGO resource is the only commercial database. Some of these databases contain manually curated and standardized gene functions (e.g. ERGO, RefSeq and Genome Reviews). Many of these databases contain gene functions compiled from various sources (e.g. GIB, GOLD, CMR, Genome Reviews, IMG, RefSeq, the SEED and ERGO).

Table 2.

Genome (re‐)annotation databases.

| Database | Organization | Description | Access/distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCBI Genbank | National Institutes of Health, USA | An annotated collection of all publicly available DNA sequences | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank | Benson et al. (2009) |

| DDBJ | DDBJ (DNA Data Bank of Japan) | General nucleotide database | http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/ | None |

| EMBL | EMBL‐EBI | Nucleotide sequence database | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/embl/ | None |

| Entrez Genome Project | National Institutes of Health, USA | Collection of complete and incomplete genome sequences | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=genomeprj | None |

| ERGO | Integrated Genomics, USA | A systems‐biology informatics toolkit for comparative genomics | http://www.integratedgenomics.com/ergo.html Commercial license | Overbeek et al. (2003) |

| Genome Reviews | EMBL‐EBI | Up‐to‐date, standardised and comprehensively annotated complete genomes | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/GenomeReviews/ | Sterk et al. (2006) |

| RefSeq | National Institutes of Health, USA | A curated non‐redundant sequence database | http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/RefSeq/ | Pruitt et al. (2009) |

| The SEED | Fellowship for Integration of Genomes (FIG) | Subsystems approach to genome annotation | http://www.theseed.org/wiki/index.php/Main_Page | Overbeek et al. (2005) |

| IMG | DOE Joint Genome Institute, USA | Integrated microbial genomes database | http://img.jgi.doe.gov | Markowitz et al. (2006); Markowitz et al. (2010) |

| Microbes Online | Virtual Institute for Microbial Stress and Survival | An integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics | http://www.microbesonline.org/ | Dehal et al. (2010) |

| CMR | J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) | Comprehensive Microbial Resource: display information on all of the publicly available, complete prokaryotic genomes | http://cmr.jcvi.org/tigr‐scripts/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi | Davidsen et al. (2010) |

| GOLD | DOE Joint Genome Institute, USA | Genomes On Line Database | http://www.genomesonline.org/ | Liolios et al. (2010) |

| Genome information broker (GIB) | DDBJ (DNA Data Bank of Japan) | Database of microbial genomes and some comparative genomic tools | http://gib.genes.nig.ac.jp/ | Fumoto et al. (2002) |

| Genome Atlas | CBS, Technical University of Denmark | DNA structural atlases for complete microbial genomes | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/GenomeAtlas/ | Hallin and Ussery (2004) |

| Pedant | Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences (MIPS) | PEDANT 3 database: a Protein Extraction, Description and ANalysis Tool | http://pedant.gsf.de | Riley et al. (2005) |

| REGANOR | CeBiTec, Germany | Gene prediction server and database | https://www.cebitec.uni‐bielefeld.de/groups/brf/software/reganor/cgi‐bin/reganor_upload.cgi Note: site offline | Linke et al. (2006) |

| BacMap | University of Alberta, Canada | An interactive picture atlas of annotated bacterial genomes | http://wishart.biology.ualberta.ca/BacMap/ | Stothard et al. (2005) |

| MOSAIC | INRA, France | Database dedicated to the comparative genomics of bacterial strains at the intra‐species level | http://genome.jouy.inra.fr/mosaic/ | Chiapello et al. (2008) |

| InterPro | EMBL‐EBI | Integrative protein signature database | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/ | Hunter et al. (2009) |

| Pfam | Sanger Institute, UK | Protein families and domains database | http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/ | Finn et al. (2010) |

| SMART | EMBL, Germany | Protein domain architecture database | http://smart.embl‐heidelberg.de/ | Letunic et al. (2009) |

| Gene Ontology Annotation (GOA) | The Gene Ontology | GO controlled vocabulary of biological processes | http://www.geneontology.org/GO.tools.annotation.shtml and http://www.ebi.ac.uk/GOA/ | Barrell et al. (2009) |

| TIGRFAMs | J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) | Assignment of molecular function and biological process | http://www.jcvi.org/cms/research/projects/tigrfams/overview/ Free to use hidden markov models | Selengut et al. (2007) |

| Pseudogene.Org | Yale Gerstein Group | A comprehensive database and comparison platform for pseudogene annotation | http://pseudogene.org | Liu et al. (2004); Karro et al. (2007) |

| ExPASy ENZYME | Swiss Institute for Bioinformatics (SIB) | Enzyme nomenclature database | http://www.expasy.ch/enzyme/ | Bairoch (2000) |

| MetaCyc | SRI International, USA | Database of metabolic pathways and enzymes | http://metacyc.org/ | Caspi et al. (2010) |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia for Genes and Genomes: Kanehisa Laboratories | A bioinformatics resource for linking genomes to life and the environment | http://www.genome.jp/kegg/ | Okuda et al. (2008) |

Many of the previous databases make use of annotation information from InterPro protein domains, Gene Ontologies (GO; controlled vocabulary of cellular functions), and TIGRFAMs (also part of Manatee, used in IGS/JCVI annotation services). The pseudogene.org database can be used to determine whether a gene in a given genome could be a pseudogene (non‐functional).

Microbes adapt to their environment by modulating parts of their metabolic and gene regulatory networks. Metabolic networks consist of gene products (enzymes) that catalyse chemical reactions where metabolic compounds are (re)used. The Enzyme Commission (EC) number is a way of classifying enzyme activity, using a nomenclature with specific numbers that are organized hierarchically to indicate the catalysed chemical reaction (ExPASy). Both the KEGG and MetaCyc databases describe the relation of gene products to metabolic pathways. In addition to (curated) annotation information, a few databases also offer bioinformatics and/or visualisation tools for comparative genomics, e.g. MOSAIC, CMR, the Seed, ERGO, GIB, xBASE, MicrobesOnline and BacMap.

(Re)‐annotation pipelines

Many of the afore‐mentioned databases contain annotation information that is generated by gene annotation pipelines. Table 3 lists annotation pipelines that are either offered as a service or that can be downloaded and installed locally. Locally running pipelines (AGMIAL, DIYA, Restauro‐G, GenVar, SABIA, MAGPIE and GenDB) have the advantage that data can be kept confidential and that the annotation process is run on local hardware, ensuring reproducible annotation times. On‐line services (IGS, IMG, JCVI, IGS, RAST, xBASE, BASys) have the advantage of simplicity and little time investment. Curation of the annotation results requires constant user interaction to view the genes in context of different annotation information. The JCVI and IGS services both use the (formerly known as TIGR) Manatee pipeline, which also uses the TIGRFAMs to detect functional domains in protein sequences. They offer the user the possibility to view and alter annotations in the respective databases they use. Similar functionality is offered by MAGE (which uses the MicroScope database) (Fig. 2), IMG‐ER (uses the IMG data model as basis) and RAST (based on the Seed). The commercially available Pedant‐Pro pipeline is based on the Pedant annotation pipeline with various enhancements. Usability of the MiGAP and ATCUG annotation pipelines could not be judged by us due to unavailable software (ATCUG) or website language in Japanese (MiGAP). The Taverna work‐flow system allows to link different web services, and has the advantage that it can be adapted by experienced bioinformaticians. Assigning genes to metabolic pathways can be done using the KAAS service (Table 3), which annotates gene products by assigning EC numbers based on amino acid similarity to gene products with known EC numbers.

Table 3.

Genome (re‐)annotation pipelines.

| Pipeline | Organization | Description | Access/distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGS | University of Maryland | A FREE resource for genomics researchers and educators bringing advanced bioinformatics tools to the lab bench and the classroom | http://ae.igs.umaryland.edu/cgi/index.cgi Free service | None |

| JCVI annotation service | J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) | Free to use genome annotation service | http://www.jcvi.org/cms/research/projects/annotation‐service/overview/ Free to use annotation service | None |

| MiGAP | Database Center for Life Sciences (DBCLS) | Microbial Genome Annotation Pipeline (MiGAP) for diverse users | http://migap.lifesciencedb.jp/ Note: site is in Japanese | http://www.jsbi.org/modules/journal1/index.php/GIW09/Poster/GIW09S001.pdf |

| MaGe/MicroScope | GENOSCOPE | Magnifying Genomes: microbial genome annotation system | http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/agc/mage Free service | Vallenet et al. (2006); Vallenet et al. (2009) |

| BASys | University of Alberta, Canada | A web server for bacterial genome annotation | http://wishart.biology.ualberta.ca/basys/ Free to use | Van Domselaar et al. (2005) |

| RAST | Fellowship for Integration of Genomes (FIG) | The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology based on the Seed | http://rast.nmpdr.org/ Free to use service | Aziz et al. (2008) |

| xBASE | University of Birmingham, UK | Bacterial genome annotation service | http://xbase.ac.uk/annotation/ Free to use service | Chaudhuri et al. (2008) |

| IMG ER | Joint Genome Institute (JGI) | A system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation | http://img.jgi.doe.gov/er Free service | Markowitz et al. (2009) |

| GenVar | Virginia Bioinformatics Institute | Bacterial gene annotation and comparative genomics pipeline | http://patric.vbi.vt.edu/downloads/software/GenVar Free for non‐commercial use | Yu et al. (2007) |

| Pedant‐Pro | Biomax | Genome analysis package for comprehensive analysis of DNA and protein sequences | http://www.biomax.de/products/pedantpro.php Commercial license | Frishman et al. (2001) |

| AGMIAL | INRA, France | An annotation strategy for prokaryote genomes as a distributed system | http://genome.jouy.inra.fr/agmial/ Open source license | Bryson et al. (2006) |

| GenDB | CeBiTec, Germany | Bacterial annotation system | http://www.cebitec.uni‐bielefeld.de/groups/brf/software/gendb_info/ Free to use, stand‐alone software | Meyer et al. (2003) |

| DIYA | DIY Genomics Consortium | A bacterial annotation pipeline for any genomics lab | https://sourceforge.net/projects/diyg/ Free to use, stand‐alone software | Stewart et al. (2009) |

| SABIA | LNCC, Brazil | Bacterial annotation system | http://www.sabia.lncc.br/ Free to use, stand‐alone software | Almeida et al. (2004) |

| MAGPIE | Genome Prairie Project, Canada | Genome annotation system | http://magpie.ucalgary.ca/ Free to use, stand‐alone software | Gaasterland and Sensen (1996) |

| Restauro‐G | Institute for Advanced Biosciences, Keio University | A Rapid Genome Re‐Annotation System for Comparative Genomics | http://restauro‐g.iab.keio.ac.jp/ Software distributed under the GNU public license | Tamaki et al. (2007) |

| ATUCG system | Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil | Agent‐based environment for automatic annotation of Genomes | None Software should be requested at authors | Nascimento and Bazzan (2005) |

| Taverna: annotation of genomes | University of Manchester | Interactive genome annotation pipeline. | http://www.taverna.org.uk/introduction/taverna‐in‐use/annotation/annotation‐of‐genomes/ | Hull et al. (2006) |

| KAAS | Kyoto Encyclopedia for Genes and Genomes (KEGG) | KEGG automated annotation service for metabolic pathways | http://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/ Free to use service | Moriya et al. (2007) |

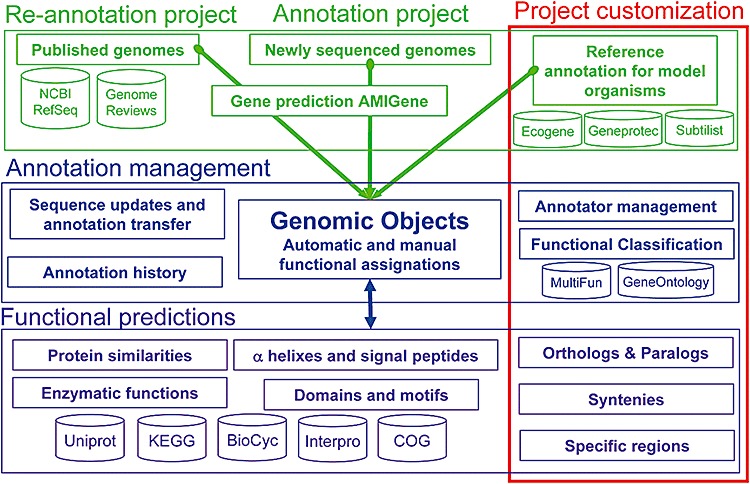

Figure 2.

Simplified prokaryotic genome database (PkGDB) relational model composed of three main components: sequence and annotation data (in green), annotation management (in blue) and functional predictions (in purple). Sequences and annotations come from public databanks, sequencing centres and specialized databases focused on model organisms. For genomes of interest, a (re)‐annotation process is performed using AMIGene (Bocs et al., 2003) and leads to the creation of new ‘Genomic Objects’. Each ‘Genomic Object’ and associated functional prediction results are stored in the PkGDB. The database architecture supports integration of automatic and manual annotations, and management of a history of annotations and sequence updates. Reproduced from Vallenet and colleagues (2006).

Once gene annotations have been determined, they can be checked for inaccurate or missing gene annotations using MICheck. Hsiao and colleagues (2010) describe an algorithm for policing gene annotations, which looks for genes with poor genomic correlations with their network neighbours, and are likely to represent annotation errors. They applied their approach to identify misannotations of B. subtilis. The Artemis generic visualisation tool can be used for manual editing of annotation (Rutherford et al., 2000). Prior to submission of a DNA sequence and annotation to the NCBI genome database, the NCBI Sequin service (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/Sequin/) also facilitates checking gene annotations, making sure that certain standards and formats are used.

Comparison of automatic annotation pipelines

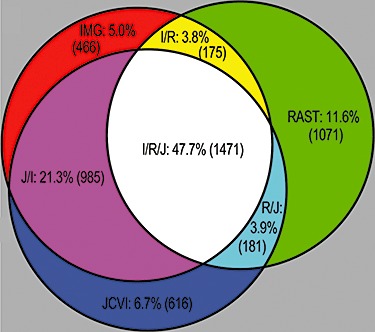

Genome annotations are accumulating rapidly and most genome centres depend heavily on automated annotation systems. But rarely has their output been systematically compared to determine accuracy and inherent errors. (Bakke and colleagues (2009) compared the automatic genome annotation services IMG, RAST and JCVI, and found considerable differences in gene calls (Fig. 3), features and ease of use. Each service provided multiple unique start sites and gene product calls as well as mistakes. They argue that the most efficient way to substantially decrease annotation error is to compare results from multiple annotation services. Aggregating data and displaying discrepancies between annotations should resolve many possible errors including false positives, uncalled genes, genes without a predicted function, incorrectly predicted functions and incorrect start sites. To accomplish multi‐annotation comparison, information must be interchangeable between annotation services, and software should be built to connect annotations in a manner that promotes easy human review. Tools that cross‐query annotations and provide side‐by‐side comparisons that include genomic context and multiple functional annotations will aid the user and decrease the amount of time required to make an accurate correction, i.e. to decrease manual curation time.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram of comparison of gene prediction in Halorhabdus utahensis using the RAST, IMG and JCVI automated annotation services. The diagram shows the number of predicted protein‐coding genes that share start site and stop site with the other annotations. Overlapping regions indicate genes having exact matches between annotations. Adapted from Bakke and colleagues (2009).

Future

Clearly, standardization of ORF calling and annotation (and re‐annotation of published genomes) is of utmost importance. A few standard operating procedures for genome annotation have already been proposed in recent years (Angiuoli et al., 2008; Mavromatis et al., 2009). Still, we are a long way from achieving that goal, and it is unlikely we will ever be able to weed out all the incorrect gene calls and inherited annotations that are abundant in present genome databases. The contents of NCBI GenBank can only be changed by the original submitters, and that rarely happens. So be aware that a blast search against GenBank may retrieve very outdated or incorrectly inherited annotations. It is wiser to blast against curated genome databases, but there are so many to choose from (Table 2), and we clearly need tools to compare annotations from different curated databases.

Re‐annotation of genomes is a never‐ending process, and any current genome annotation is only a snap‐shot. New information emerges almost every day from re‐sequencing, experimentation (e.g. transcriptomics, proteomics, phenotypic tests, gene knock‐outs), comparative genomics, etc. Salzberg (2007) has proposed that a ‘genome wiki’ might provide just the solution we need for genome annotation. A wiki would allow the community of experts to work out the best name for each gene, to indicate uncertainty where appropriate, to include experimental evidence, to discuss alternative annotations, and to continuously update annotations. Although wikis will not (and should not) supplant well‐curated model‐organism databases, for the majority of species they might represent our best chance for creating accurate, up‐to‐date genome annotation.

And if you are really serious about updating your annotations, don't forget to re‐sequence your original strains using next‐generation sequencing, at least if you can still find them in your freezer!

Acknowledgments

This project was carried out within the research programmes of the Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation and the Netherlands Bioinformatics Centre, which are part of the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

References

- Almeida L.G., Paixao R., Souza R.C., Costa G.C., Barrientos F.J., Santos M.T. A system for automated bacterial (genome) integrated annotation – SABIA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2832–2833. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth273. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI‐BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angiuoli S.V., Gussman A., Klimke W., Cochrane G., Field D., Garrity G. Toward an online repository of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for (meta)genomic annotation. OMICS. 2008;12:137–141. doi: 10.1089/omi.2008.0017. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz R.K., Bartels D., Best A.A., DeJongh M., Disz T., Edwards R.A. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A. The ENZYME database in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:304–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakke P., Carney N., Deloache W., Gearing M., Ingvorsen K., Lotz M. Evaluation of three automated genome annotations for Halorhabdus utahensis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006291. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe V., Cruveiller S., Kunst F., Lenoble P., Meurice G., Sekowska A. From a consortium sequence to a unified sequence: the Bacillus subtilis 168 reference genome a decade later. Microbiology. 2009;155:1758–1775. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.027839-0. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrell D., Dimmer E., Huntley R.P., Binns D., O'Donovan C., Apweiler R. The GOA database in 2009 – an integrated Gene Ontology Annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D396–D403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson D.A., Karsch‐Mizrachi I., Lipman D.J., Ostell J., Sayers E.W. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D26–D31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocs S., Cruveiller S., Vallenet D., Nuel G., Medigue C. AMIGene: Annotation of MIcrobial Genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3723–3726. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson K., Loux V., Bossy R., Nicolas P., Chaillou S., Van De Guchte M. AGMIAL: implementing an annotation strategy for prokaryote genomes as a distributed system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3533–3545. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl471. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camus J.C., Pryor M.J., Medigue C., Cole S.T. Re‐annotation of the genome sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Microbiology. 2002;148:2967–2973. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi R., Altman T., Dale J.M., Dreher K., Fulcher C.A., Gilham F. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D473–D479. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp875. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri R.R., Loman N.J., Snyder L.A., Bailey C.M., Stekel D.J., Pallen M.J. xBASE2: a comprehensive resource for comparative bacterial genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D543–D546. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiapello H., Gendrault A., Caron C., Blum J., Petit M.A., EI Karoui M. MOSAIC: an online database dedicated to the comparative genomics of bacterial strains at the intra‐species level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:498. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie K.R., Weng S., Balakrishnan R., Costanzo M.C., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S. Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) provides tools to identify and analyze sequences from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and related sequences from other organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D311–D314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh033. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsen T., Beck E., Ganapathy A., Montgomery R., Zafar N., Yang Q. The comprehensive microbial resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D340–D345. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp912. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehal P.S., Joachimiak M.P., Price M.N., Bates J.T., Baumohl J.K., Chivian D. MicrobesOnline: an integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D396–D400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp919. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher A.L., Harmon D., Kasif S., White O., Salzberg S.L. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4636–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S.R. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R.D., Mistry J., Tate J., Coggill P., Heger A., Pollington J.E. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman D., Albermann K., Hani J., Heumann K., Metanomski A., Zollner A., Mewes H.W. Functional and structural genomics using PEDANT. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:44–57. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumoto M., Miyazaki S., Sugawara H. Genome Information Broker (GIB): data retrieval and comparative analysis system for completed microbial genomes and more. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:66–68. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaasterland T., Sensen C.W. MAGPIE: automated genome interpretation. Trends Genet. 1996;12:76–78. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)81406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundogdu O., Bentley S.D., Holden M.T., Parkhill J., Dorrell N., Wren B.W. Re‐annotation and re‐analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168 genome sequence. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallin P.F., Ussery D.W. CBS Genome Atlas Database: a dynamic storage for bioinformatic results and sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3682–3686. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao T.L., Revelles O., Chen L., Sauer U., Vitkup D. Automatic policing of biochemical annotations using genomic correlations. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:34–40. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull D., Wolstencroft K., Stevens R., Goble C., Pocock M.R., Li P., Oinn T. Taverna: a tool for building and running workflows of services. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W729–W732. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter S., Apweiler R., Attwood T.K., Bairoch A., Bateman A., Binns D. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karro J.E., Yan Y., Zheng D., Zhang Z., Carriero N., Cayting P. Pseudogene.org: a comprehensive database and comparison platform for pseudogene annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D55–D60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl851. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst F., Ogasawara N., Moszer I., Albertini A.M., Alloni G., Azevedo V. The complete genome sequence of the gram‐positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechat P., Hummel L., Rousseau S., Moszer I. GenoList: an integrated environment for comparative analysis of microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D469–D474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Doerks T., Bork P. SMART 6: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D229–D232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke B., McHardy A.C., Neuweger H., Krause L., Meyer F. REGANOR: a gene prediction server for prokaryotic genomes and a database of high quality gene predictions for prokaryotes. Appl Bioinformatics. 2006;5:193–198. doi: 10.2165/00822942-200605030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liolios K., Chen I.M., Mavromatis K., Tavernarakis N., Hugenholtz P., Markowitz V.M., Kyrpides N.C. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D346–D354. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Harrison P.M., Kunin V., Gerstein M. Comprehensive analysis of pseudogenes in prokaryotes: widespread gene decay and failure of putative horizontally transferred genes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashin A.V., Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Hu G.Q., Zhu H. Genome reannotation of Escherichia coli CFT073 with new insights into virulence. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:552. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz V.M., Chen I.M., Palaniappan K., Chu K., Szeto E., Grechkin Y. The integrated microbial genomes system: an expanding comparative analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D382–D390. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp887. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz V.M., Korzeniewski F., Palaniappan K., Szeto E., Werner G., Padki A. The integrated microbial genomes (IMG) system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D344–D348. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj024. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz V.M., Mavromatis K., Ivanova N.N., Chen I.M., Chu K., Kyrpides N.C. IMG ER: a system for microbial genome annotation expert review and curation. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2271–2278. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavromatis K., Ivanova N.N., Chen I.A., Szeto E., Markowitz V.M., Kyrpides N.C. The DOE‐JGI standard operating procedure for the annotations of microbial genomes. Standards in Genomics Sciences. 2009;1:68–71. doi: 10.4056/sigs.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F., Goesmann A., McHardy A.C., Bartels D., Bekel T., Clausen J. GenDB – an open source genome annotation system for prokaryote genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2187–2195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg312. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y., Itoh M., Okuda S., Yoshizawa A.C., Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W182–W185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento L.V., Bazzan A.L. An agent‐based system for re‐annotation of genomes. Genet Mol Res. 2005;4:571–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda S., Yamada T., Hamajima M., Itoh M., Katayama T., Bork P. KEGG Atlas mapping for global analysis of metabolic pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W423–W426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn282. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounis C.A., Karp P.D. The past, present and future of genome‐wide re‐annotation. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-comment2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R., Begley T., Butler R.M., Choudhuri J.V., Chuang H.Y., Cohoon M. The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5691–5702. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki866. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R., Larsen N., Walunas T., D'Souza M., Pusch G., Selkov E., Jr The ERGO genome analysis and discovery system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:164–171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg148. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt K.D., Tatusova T., Klimke W., Maglott D.R. NCBI Reference Sequences: current status, policy and new initiatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley M.L., Schmidt T., Wagner C., Mewes H.W., Frishman D. The PEDANT genome database in 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D308–D310. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd K.E. EcoGene: a genome sequence database for Escherichia coli K‐12. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:60–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K., Parkhill J., Crook J., Horsnell T., Rice P., Rajandream M.A., Barrell B. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg S.L. Genome re‐annotation: a wiki solution? Genome Biol. 2007;8:102. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selengut J.D., Haft D.H., Davidsen T., Ganapathy A., Gwinn‐Giglio M., Nelson W.C. TIGRFAMs and Genome Properties: tools for the assignment of molecular function and biological process in prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D260–D264. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1043. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterk P., Kersey P.J., Apweiler R. Genome Reviews: standardizing content and representation of information about complete genomes. OMICS. 2006;10:114–118. doi: 10.1089/omi.2006.10.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A.C., Osborne B., Read T.D. DIYA: a bacterial annotation pipeline for any genomics lab. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:962–963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard P., Van Domselaar G., Shrivastava S., Guo A., O'Neill B., Cruz J. BacMap: an interactive picture atlas of annotated bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D317–D320. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki075. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki S., Arakawa K., Kono N., Tomita M. Restauro‐G: a rapid genome re‐annotation system for comparative genomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2007;5:53–58. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60014-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallenet D., Engelen S., Mornico D., Cruveiller S., Fleury L., Lajus A. MicroScope: a platform for microbial genome annotation and comparative genomics. Database (Oxford) 2009;2009:bap021. doi: 10.1093/database/bap021. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallenet D., Labarre L., Rouy Z., Barbe V., Bocs S., Cruveiller S. MaGe: a microbial genome annotation system supported by synteny results. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:53–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj406. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Domselaar G.H., Stothard P., Shrivastava S., Cruz J.A., Guo A., Dong X. BASys: a web server for automated bacterial genome annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W455–W459. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki593. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood V., Rutherford K.M., Ivens A., Rajandream M.A., Barrell B. A re‐annotation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Comp Funct Genomics. 2001;2:143–154. doi: 10.1002/cfg.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortman J.R., Gilsenan J.M., Joardar V., Deegan J., Clutterbuck J., Andersen M.R. The 2008 update of the Aspergillus nidulans genome annotation: a community effort. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46(1):S2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.12.003. et al (Suppl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Pappas K.M., Hauser L.J., Land M.L., Chen G.L., Hurst G.B. Improved genome annotation for Zymomonas mobilis. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:893–894. doi: 10.1038/nbt1009-893. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.X., Snyder E.E., Boyle S.M., Crasta O.R., Czar M., Mane S.P. A versatile computational pipeline for bacterial genome annotation improvement and comparative analysis, with Brucella as a use case. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3953–3962. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm377. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]