Abstract

Poly-γ-glutamate (PGA), a novel polyamide material with industrial applications, possesses a nylon-like backbone, is structurally similar to polyacrylic acid, is biodegradable and is safe for human consumption. PGA is frequently found in the mucilage of natto, a Japanese traditional fermented food. To date, three different types of PGA, namely a homo polymer of d-glutamate (D-PGA), a homo polymer of l-glutamate (L-PGA), and a random copolymer consisting of d- and l-glutamate (DL-PGA), are known. This review will detail the occurrence and physiology of PGA. The proposed reaction mechanism of PGA synthesis including its localization and the structure of the involved enzyme, PGA synthetase, are described. The occurrence of multiple carboxyl residues in PGA likely plays a role in its relative unsuitability for the development of bio-nylon plastics and thus, establishment of an efficient PGA-reforming strategy is of great importance. Aside from the potential applications of PGA proposed to date, a new technique for chemical transformation of PGA is also discussed. Finally, some techniques for PGA and its derivatives in advanced material technology are presented.

Introduction

Most plastics and synthetic polymers, such as nylons and acrylic materials, are derived from petrochemicals. These long-lasting polymers are used even for short-lived applications leading to a profound influence on the environment. Plastic materials that are improperly disposed of are serious sources of environmental pollution. The elimination of waste plastics is therefore of value in the following disciplines: surgery, health, catering, packing, agriculture, fishing, environmental protection and other technical endeavours. Increased knowledge of the value of the preservation of environmental systems has resulted in a complete change in the production of conventional and non-degradable polymers. The ultimate goal is to produce earth-friendly biodegradable polymers that will contribute to savings in energy and resources, help to curb the greenhouse effect, encourage the development of eco-compatible processes and products, and diversify agriculture for food production.

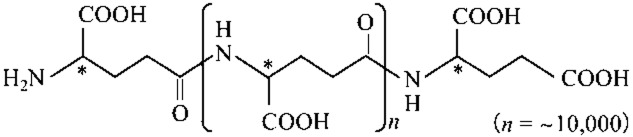

A biopolymer with a nylon-like backbone and structurally similar to polyacrylic acid, poly-γ-glutamate (PGA; Fig. 1), is attracting commercial interest (Bajaj and Singhal, 2011). If PGA is lyophilized so that its moisture content is < 5% of its total weight, it possesses thermoplastic properties (Ashiuchi et al., 2013a), and PGA with multiple chirotopic carbons is fairly biodegradable (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002). Currently, two distinct PGA-reforming strategies, esterification (Yahata et al., 1992) and polymer γ-irradiation techniques (Choi and Kunioka, 1995), have been proposed. Indeed, they may provide plastics and hydrogels; however, the merits in environment and industry (e.g. biodegradability and recyclability) of these newly created polymers cannot be assumed on the basis of those of PGA itself because of the irreversible modification of the PGA chains. Hereafter, it is desired that PGA is transformed into plastics by strong but reversible binding with certain common (and preferably safe) chemicals. PGA should be recovered via the liberation of such chemicals from the waste materials. In the study, this idea is tentatively called ‘chemical transformation’ of polymers.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of PGA. The backbone is virtually the same as that of a chemically synthesized (and achiral), high-performance polyamide material, such as nylon-4 (Ashiuchi, 2011). The chirotopic carbon(s) of PGA are usually indicated with asterisk(s).

This review focuses on the occurrence and physiology of PGA (as a basis for obtaining a better understanding of its microbial production), polymer synthesis and localization (towards the creation and designing of genetically engineered mass producers of PGA), its potential applications (for bioremediation, functional food ingredients, health care, pharmaceutics and advanced biochemistry), and its chemical transformation (towards the development of feasible bio-nylons).

Occurrence and physiology

To date, three different types of PGA have been identified (Table 1): the homo polymer of d-glutamate (D-PGA), the homo polymer of l-glutamate (L-PGA), and the random copolymer consisting of d- and l-glutamate (DL-PGA). Current information about the molecular physiology of PGA implies that it functions as an adaptation agent in various environments.

Table 1.

Biochemical comparisons of some PGA producers

| Producers | Molecular masses (kDa) | Stereo-chemistry (d-Ratios; %) | d-Glu-supplying enzyme candidates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | 10–10000 | 20–80 | GLR, DAT |

| Bacillus anthracis | n.d. | 100 | GLR, DAT |

| Bacillus megaterium | > 1000 | 5–10 | GLR, DAT |

| Bacillus halodurans | < 20 | 0 | GLR, DAT |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | n.d. | 40–50 | GLR, DAT |

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | n.d. | n.d. | GLR |

| Archaea | |||

| Natrialba aegyptiaca | > 1000 | 0 | – |

| Natronococcus occultus | < 20 | 0 | – |

GLR, glutamate racemase; DAT, d-amino acid aminotransferase; –, absence of any d-glutamate-supplying enzymes. n.d., not determined.

DL-PGA producers

DL-PGA is found in the mucilage of a Japanese fermented soybean food known as natto (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002). Some strains of Bacillus subtilis are traditionally utilized as the natto starter (Sawamura, 1913). DL-PGA producers of Bacillus are classified into two groups: exogenous glutamate-dependent and -independent groups. B. subtilis IFO 3335 (Kunioka and Goto, 1994); MR-141 (Ogawa et al., 1997); F-2-01 (Kubota et al., 1993); subsp. chungkookjang (Ashiuchi et al., 2001a) and Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 9945A (Thorne et al., 1954; Leonard and Housewright, 1963; Cromwick and Gross, 1995; Pérez-Camero et al., 1999) are included in the former category. B. subtilis 5E (Shih and Van, 2001); TAM-4 (Ito et al., 1996) and B. licheniformis A35 (Cheng et al., 1989); S173 (Kambourova et al., 2001) belong to the latter group. Bacillus DL-PGA is generally accumulated in culture media ( Table 2) and therefore is considered a long-chain exo-polymer with various molecular masses of 250 to 5000 kDa (Park et al., 2005).

Table 2.

Over-accumulation of PGA in media by B. subtilis and its related strains (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002)

| Strains | Important components in media | Culture conditions | Yield (g l−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate-dependent PGA producers | |||

| B. subtilis IFO 3335 | L-Glutamate (30 g l−1); (NH4)2SO4 (30 g l−1); citric acid (20 g l−1) | 37°C, 2 days | 10–20 |

| B. licheniformis ATCC 9945A | L-Glutamate (20 g l−1); NH4Cl (7 g l−1); citric acid (12 g l−1); CaCl2 (0.2 g l−1); MnSO4.7H2O (0.3 g l−1) | 37°C, 2–3 days | 35 |

| B. subtilis (natto) MR-141 | L-Glutamate (30 g l−1); maltose (60 g l−1); soy sauce (70 g l−1) | 40°C, 3–4 days | 35 |

| B. subtilis subsp. chungkookjang | L-Glutamate (20 g l−1); sucrose (50 g l−1); NaCl (0.5-5.0 g l−1) | 30°C, 5 days | 13.5–16.5 |

| B. subtilis F-2-01 | L-Glutamate (70 g l−1); glucose (1 g l−1); veal infusion broth (20 g l−1) | 30°C, 2–3 days | 50 |

| Glutamate-independent PGA producers | |||

| B. subtilis TAM-4 | NH4Cl (18 g l−1); fructose (75 g l−1) | 30°C, 4 days | 20 |

| B. licheniformis A35 | NH4Cl (18 g l−1); glucose (75 g l−1); MnSO4.7H2O (0.04 g l−1); HNO3 (20 g l−1) | 30°C, 3–5 days | 8–12 |

| B. licheniformis S173 | NH4Cl (4 g l−1); citric acid (20 g l−1); Mn2+, Fe2+, Ca2+, Zn2+ (1 mM each) | 37°C, 30 h | 1.27 |

Other than Bacillus, some strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis also produce DL-PGA as a capsular polymer for evading mammalian immune defence mechanisms (Kocianova et al., 2005).

D-PGA producer

Microbial PGA production was discovered for the first time in Bacillus anthracis (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002), and, to our knowledge, this is the only sole D-PGA producer among those identified so far (Table 1). Although D-PGA itself is avirulent in mammals, its capsular form completely nullifies the immunity of hosts and eventually promotes severe anthrax symptoms (Keppie et al., 1963).

L-PGA producers

An extremely halophilic archaeon, i.e. Natrialba aegyptiaca (Hezayen et al., 2001), produces long-chain L-PGA (with molecular masses of more than 1000 kDa) for the prevention of drastic dehydration under extremely high-saline conditions (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002). Interestingly, salt-inducible PGA (l-glutamate content, ∼95%) was also identified from a halotolerant bacterium, Bacillus megaterium (Shimizu et al., 2007).

Bacillus halodurans (Aono, 1987) and Natronococcus occultus (Niemetz et al., 1997) produce short-chain L-PGA (with molecular masses of less than 20 kDa) as a secondary cell-wall polymer (e.g. teichuronopeptide) for neutralization of the near-cell surfaces, causing extreme alkalophilicity. Short-chain l-PGA was further identified as the major constituent of sticky substances in the nematocysts of cnidarians (e.g. hydra) as well as the generator (or regulator) of internal osmotic pressure in these organisms (Weber, 1989; 1990).

Biosynthesis

Some B. subtilis PGA producers (Table 2) may have potential industrial application. However, in reality, the polymer productivity and quality may vary dramatically depending on small differences in cultivation factors such as the ionic strength of media, aeration, temperature and culture time. Thus, the establishment of reproducible PGA mass-production techniques is of great urgency.

Reaction mechanism

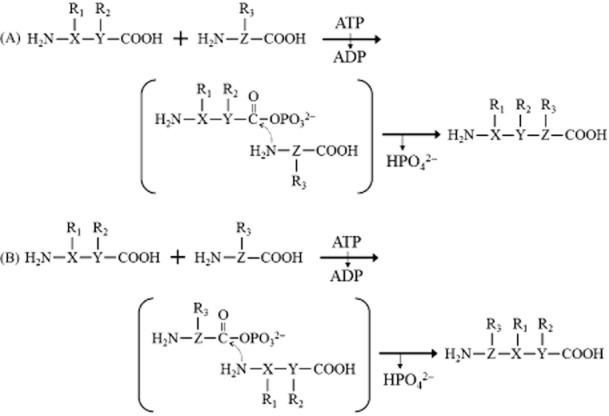

Elucidation of the mechanism reproducible for the synthesis of PGA would be indispensable for obtaining a better understanding of enzymes involved in its synthesis. Based on the structural features of PGA, such as the introduction of non-proteinaceous d-glutamate and its unusual γ-amide linkage formula, the existence of a novel enzyme that can catalyze non-ribosomal glutamate ligation (viz., polymerization) is predicted. Moreover, the nucleotide formed by coincident ATP hydrolysis is ADP, not AMP (Ashiuchi et al., 2001b; Urushibata et al., 2002), revealing that PGA is synthesized in an amide-ligation manner (Ashiuchi, 2010). The amide-ligation mechanism is catalyzed by typical amide ligases with a Rossmann-like fold such as murein-biosynthetic enzymes (Eveland et al., 1997), or ATP-dependent (ADP-forming) carboxylate-amine/thiol ligases (peptide synthetases) with ATP-grasp domain(s), including glutathione synthetase and d-alanine-d-alanine ligase (Galperin and Koonin, 1997). Both types of amide ligases are commonly characterized by a lack of isomerization activity for amino acid residues in a growing chain, resulting in the substrate having the same stereochemistry as the polymer produced. Therefore, d-amino acid residues in polyamides generated via the amide-ligation mechanism will be derived from free d-amino acids in cells (Ashiuchi et al., 2013b). Ashiuchi and colleagues (2004) actually found a membrane-associated DL-PGA synthetic activity from B. subtilis subsp. chungkookjang, in which both d- and l-glutamate served as direct substrates. Interestingly, there is a noteworthy difference in the proposed catalytic mechanisms of amide ligases (Fig. 2), namely that the Rossmann-type enzymes activate the C-terminal carboxyl residue of the polymers (as the acceptor in peptide elongation; Sheng et al., 2000), whereas the ATP-grasp-type enzymes generally phosphorylate the carboxyl group of donor substrates (Fan et al., 1995; Kino et al., 2009). This may sometimes cause a lack of stereo-exactitude in the former enzymes, resulting in dl-copolymer production. Ashiuchi and colleagues (2001b) previously observed that there was no phosphorylation activity for the monomers of glutamate during the elongation reaction with a B. subtilis DL-PGA synthetase, predicting that the enzyme will belong to the superfamily of Rossmann-type amide ligases (Eveland et al., 1997).

Figure 2.

Proposed reaction mechanisms of amide ligases containing either a Rossmann-like fold (A) or ATP-grasp domain (B). In the reaction schemes, X, Y and Z indicate the moieties containing a chirotopic carbon; R1, R2 and R3 are the side chains (viz., amino acid residues). In the case of poly-α-glutamate synthesis, XYZ and R1,2,3 are represented as –*CH– and –(CH2)2–COOH respectively, whereas the former and the latter are altered to –*CH–(CH2)2– and –COOH in poly-γ-glutamate (PGA) synthesis, for instance.

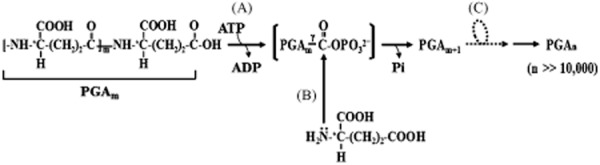

The mechanism for DL-PGA synthesis has been proposed (Fig. 3): step (A), the transfer of the phosphoryl group of ATP to the C-terminal carboxyl group of a growing chain and the release of the resulting ADP from the active site of the enzyme; step (B), the formation of an amide linkage via nucleophilic attack of the amino group of either a d- or l-glutamate on the phosphorylated carboxyl group; and step (C), the export of DL-PGA after multiple iterations of steps (A) and (B) within the enzyme. In principle, PGA is not covalently bound to a membrane-associated enzyme at any stage.

Figure 3.

Proposed reaction mechanism for PGA production (Ashiuchi, 2010). Detailed explanation about the reactions steps is described in the Biosynthesis subsection ‘Reaction mechanism’.

Molecular enzymology

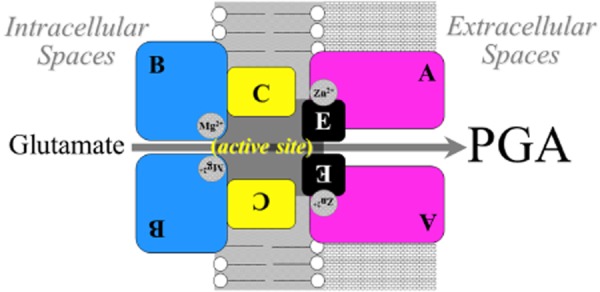

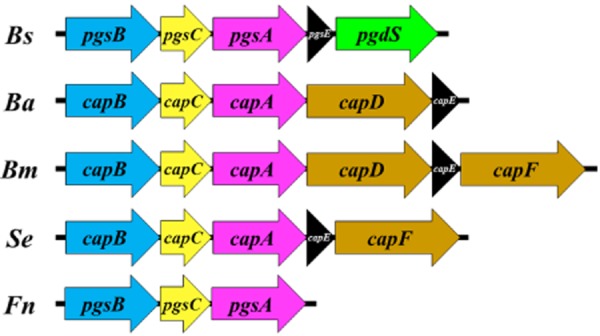

As expected, current research supports the idea that DL-PGA synthetase is a membrane-associated modular protein complex (viz., PgsBCAE) with a Rossmann-type amide ligase-like PgsB component (Fig. 4; Ashiuchi et al., 1999; 2001b; Urushibata et al., 2002). Research has also been published on the operon organization and molecular machinery involved in D-PGA synthesis in B. anthracis (Candela and Fouet, 2006), the L-rich PGA synthesis carried out by B. megaterium (DDBJ accession no., AB571872), the DL-PGA synthesis by S. epidermidis (Kocianova et al., 2005) and the PGA synthesis by Fusobacterium nucleatum (Candela et al., 2009). All are homologous to the DL-PGA synthesis carried out by B. subtilis (Fig. 5). These bacteria possess the responsible genes for d-glutamate synthesis (Kunst et al., 1997; Kapatral et al., 2002; Read et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; Eppinger et al., 2011) and generally demonstrate the associated enzyme activities in varying amounts (Table 1). In contrast, N. aegyptiaca, which is capable of producing long-chain L-PGA, does not contain any pathways for d-glutamate supply (Ashiuchi et al., 2013b). B. halodurans has the machinery to potentially participate in d-glutamate synthesis similar to other bacilli (Takami et al., 2000), though it can produce L-PGA in the absence of d-glutamyl residues. It is noteworthy that neither the pgs nor cap operon is found in the B. halodurans genome (Takami et al., 2000), because this strongly implies the participation of an unidentified system: for example, novel L-PGA synthetase(s) with an ATP-grasp domain.

Figure 4.

Proposed complex structure of PGA synthetase from B. subtilis. All the components of PGA synthetase are essentially membrane associated (Urushibata et al., 2002; Ashiuchi, 2010; Ashiuchi et al., 2013c).

Figure 5.

Gene operons for microbial PGA production. Bs, B. subtilis; Ba, B. anthracis; Bm, B. megaterium; Se, S. epidermidis; and Fn, F. nucleatum. PgsB (CapB) and PgsC (CapC) are structurally similar to a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the addition of a short γ-l-glutamyl chain to a folate moiety (FolC) and the N-acetyltransferase-domain of N-acetylglutamate synthetase respectively. PgsA (CapA) reveals the homology with cytosolic protein serine/threonine phosphatases. PgsE (CapE) is a potent stimulator of PGA production with an assembly accelerator-like structure (Yamashiro et al., 2011; Ashiuchi et al., 2013c). Detailed information about PgdS and CapD/F is described in the Localization section.

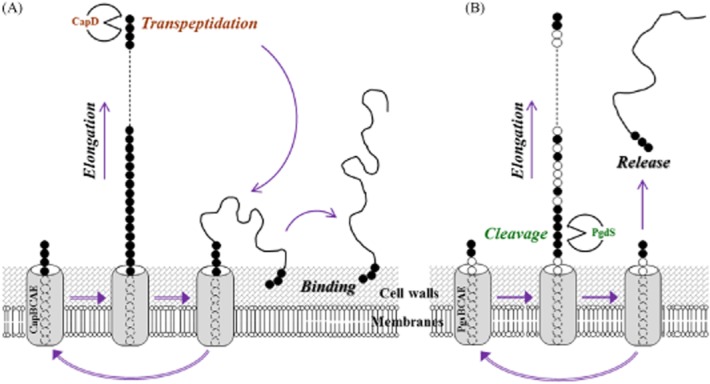

Localization

PGA is mainly found as a capsular polymer; therefore, its accumulation as an exo-polymer, as observed for B. subtilis and B. licheniformis, the PGA synthetic system of which is virtually the same as that of B. subtilis (Wang et al., 2011; Yangtse et al., 2012), is currently considered a peculiar phenomenon. Comparative genetic analysis of the pgs and cap operons (Fig. 5) reveals a difference in their downstream genes for PGA cleavage. In fact, B. anthracis CapD is essential for the covalent anchoring of D-PGA to peptidoglycans in the cell walls (Fig. 6A; Candela and Fouet, 2006). B. megaterium CapD and CapF and S. epidermidis CapF structurally resemble the B. anthracis enzyme. It was first characterized as an exo-type of γ-glutamyltransferase, whereas B. subtilis PgdS was identified as an endo-type of amidase that catalyzes the γ-glutamyl dd-amidohydrolysis of DL-PGA (Ashiuchi et al., 2006). It therefore seems likely that the latter enzyme, different from the former enzyme, has potential to participate in the stimulated release of PGA in vivo (Fig. 6B). Further studies on the localization of F. nucleatum PGA may be helpful to understanding the function of PgdS enzymes, as any structural gene that corresponds to pgdS was absent in the pgs operon of F. nucleatum (Kapatral et al., 2002; see Fig. 5). Although the physiological roles of extracellular PGA remain obscure (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002), Pgs systems should prove more useful as a PGA mass-producer(s) than Cap systems.

Figure 6.

Proposed localization mechanisms of PGA. (A) B. anthracis Cap system including CapD enzyme. (B) B. subtilis Pgs system with PgdS enzyme. Symbols in elongated polymer structures: closed circles, d-glutamyl residues; and open circles, l-glutamyl residues of PGA.

Potential applications

Because PGA, regardless of its stereochemistry, is non-toxic to humans and the environment and is even edible, this chiral-polyamide material is of interest to those in material engineering and related industries. In fact, a wide range of unique applications have been developed (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002; see Table 3).

Table 3.

Potential applications of PGA

| Categories | Applications | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Bioremediation | Flocculants | Substitution for petrochemically synthesized flocculants, such as polyacrylate gels |

| Metal absorbents | Removal of heavy metals and radionuclides | |

| Ingredients | Cryoprotectants | Preservation of cryolabile nutrients |

| Bitterness-relieving agents | Relief of bitter tastes from amino acids, peptides, quinine, caffeine, and minerals | |

| Thickeners | Viscosity enhancement for drinks; improvement of food texture; prevention of aging in foods such as bakery products and noodles | |

| Mineral absorbents | Promotion of absorption of bioavailable minerals, such as Ca2+, resulting in increase in egg-shell strength; decrease in body fat of livestock; prevention of human osteoporosis | |

| Health care | Humectants | Use in cosmetic skin-care products |

| Dispersants | Uses in detergents, cosmetics, sanitary materials | |

| Pharmaceutics | Drug delivery | Improvement of anticancer drugs; nanoparticle medicines |

| Gene vectors | Use for gene therapy | |

| Curable adhesives | Substitution of fibrin and other synthetic adhesives | |

| Biochemistry | Functional membranes | Separation of metal ions; enantioselection of amino acids |

| Extremolytes | Improvement of stability and versatility of macromolecules, enzymes, and bioactive substances |

Bioremediation

Since the Industrial Revolution, we have been releasing into the environment various pollutants such as heavy metals, radionuclides and chemicals that threaten public health and increase the likelihood of a universal shortage of provisions due to profound contamination leading to reduced agricultural output, contaminated water and effects such as acid rain. The remediation of contaminated soils, sediments and waters presents a tremendous challenge, and understanding the interaction of these pollutants with PGA may provide a basis for developing new remediation technologies.

Pötter and colleagues (2001) established a new biological technique that solves serious environmental problems caused by the use of large amounts of liquid manure in intensified agriculture: the reduction of excess NH3 in soil and the conversion of the nitrogen into PGA. PGA functions not only as a transit depot for waste nitrogen but also as an earth-friendly fertilizer by which naturally occurring bioavailable cations, such as Fe2+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Zn2+, Mg2+ and Mn2+, can be temporarily condensed and more efficiently transferred to plant rhizospheres (Kinnersley et al., 1994).

With the aim of wide adoption in wastewater treatment, dredging and industrial downstream processes, PGA flocculants were developed (Yokoi et al., 1995; 1996; Shih et al., 2001). In the future, such bio-based flocculants may be used for rapid drinking water purification in addition to downstream processing in food and fermentation industries.

PGA has the potential to be a good absorbent for both bioavailable and toxic cations including rare metals (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002). Moreover, the biopolymer can bind even an ionic radionuclide, i.e. U4+ (He et al., 2000), indicating that it may be useful for the removal (or recovery) of heavy metals and radionuclides.

Functional food ingredients

Current research has highlighted various uses of PGA as a functional food ingredient, for example in cryoprotectants, bitterness-relieving agents, thickeners and mineral absorbents (Shih and Van, 2001; see Table 3).

Frequent freezing and thawing cycles cause undesirable deterioration in living cells and bioactive substances, and results in unstable food nutrients. The cyroprotectant properties of PGA (Birrer et al., 1994; Mitsuiki et al., 1998; Yamasaki et al., 2010) makes it suitable for the preservation of cryolabile nutrients.

Bone mass decreases more with increasing aging. Osteoporosis, a significant condition affecting mostly elderly women, arises by a dramatic deterioration of bone density (Price, 1985). Tanimoto and colleagues (2001) found that PGA increased Ca2+ solubility in vitro and in vivo, resulting in intestinal Ca2+ absorption. Functional foods supplemented by a proper quantity of PGA may therefore serve as a therapeutic tool for osteoporosis treatment.

Health care

Based on the fact that PGA has potential applications in water absorption and surface adhesion, some high-performance humectants and dispersants have been developed (Shih and Van, 2001) and utilized in the cosmetic and sanitary industries.

Pharmaceutics

Many drugs, despite showing great potential as chemotherapeutic agents against human malignancies, have been difficult to use in clinical settings due to their water insolubility (Rowinsky and Donehower, 1995). However, the repurposing of some anticancer drugs is likely to be accomplished via the conjugation to water-soluble materials such as short-chain PGAs to the drug (Kishida et al., 1998; Kim et al., 1999; Li et al., 1999; Shih and Van, 2001).

PGA is not only considered to be useful as a vector for gene therapy (Dekie et al., 2000), but as a main component of nanoparticle drugs (Akagi et al., 2007; Prencipe et al., 2009).

To create high-performance adhesives applicable for use in humans, PGA glues have been proposed (Otani et al., 1998; Sekine et al., 2000). In fact, their mechanical properties were demonstrated to be superior to those of available glues made from fibrins of human blood (Spotniz, 2012).

Advanced biochemistry

PGA is likely to contribute to the development of advanced biochemical technologies. In the design of functional membranes for metal separation (Bhattacharyya et al., 1998) and for enantioselection of amino acids (Lee and Frank, 2002), chemically synthesized poly-α-glutamate (α-PGA) has been employed as a surface-modified material. Hereafter, naturally occurring PGA may replace α-PGA, as the former has significant advantages over the latter in terms of production cost and output, structural features (e.g. molecular size), and environmental impact (e.g. biodegradability).

Recent literature revealed the extremolyte-like functionality of PGA (Yamasaki et al., 2010), implying that PGA-coated enzymes may be useful even under extreme conditions where enzymes are usually inactivated: high salt concentrations, dried milieu, extremely low temperatures and high pH. In the near future, PGA may be also used for the processing of conditionally labile macromolecules including DNA and polysaccharides (Tachaboonyakiat et al., 2000).

Chemical transformation

Most of today's plastics are only minimally degraded in nature, and some of the raw materials are harmful to the human body (Dearfield and Abermathy, 1988). To make matters worse, the incineration of waste plastics often generates various endocrine disrupters such as dioxins. Hence, the development of environmentally friendly bio-based plastics is urgently required.

PGA is promising as a novel nylon (polyamide) plastic, although it is not a thermoplastic under ambient humidity. In fact, attempts to use it for industrial purposes for producing important water-insoluble materials such as plastics, fibers and films have been largely unsuccessful because of its hygroscopic nature (Ashiuchi et al., 2013a), and the fact that the occurrence of multiple carboxyl residues in PGA makes its plasticization difficult (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002). Thus, it is necessary to design a method that is effective at transforming the structure and function of the PGA carboxyl so that it can be converted to a water-insoluble bio-nylon material.

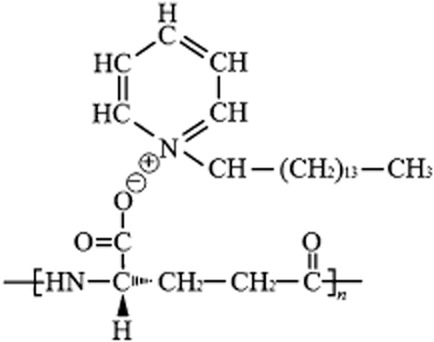

Plasticization and nanofabrication of PGA

Ashiuchi and colleagues (2013a) recently demonstrated that a compound used in toothpaste, called hexadecylpyridinium cation (HDP+), serves as a potent candidate to suppress the extreme hydrophilicity of PGA. In fact, a water-insoluble complex was readily formed by mixing PGA and HDP+ at 60°C for 30 min. The nuclear magnetic resonance analysis revealed that it is a stoichiometric ion-complex containing equal number of the carboxyl groups of PGA and HDP+ (Fig. 7). This complex is currently called PGAIC. The calorimetric assay of PGAIC implied that it possesses the potential to form a thermoplastic, which could be easily processed into a variety of the shapes and sizes via a simple pressurization. Although PGAIC is an ionic complex, it was unexpectedly stable to chemicals such as salts, acids and alkalis, suggesting the involvement of a driving force in the solidification of PGAIC other than a typical ionic interaction. It is noteworthy that PGAIC exhibits good solubility in alcohols (Ashiuchi et al., 2013a), whereas PGA itself never dissolves in alcohols. These transformable properties must be taken into account when processing PGA for diverse applications.

Figure 7.

Predicted molecular structure of PGAIC comprised of L-PGA and HDP+ (Ashiuchi et al., 2013a).

Ashiuchi and colleagues (2013a) also succeeded in synthesizing a stable PGA-based nanofiber without a covalent crosslinking (Wang et al., 2012), but by using only an ethanol solution of PGAIC. The use of cationic surfactants (e.g. HDP+) is likely to provide a promising strategy for fabricating water-friendly anionic polymers (e.g. PGA).

Antimicrobial performance of plasticized PGA material, PGAIC

The plasticized PGA material, PGAIC, strongly suppressed the proliferation of Gram-negative (Escherichia coli), Gram-positive (B. subtilis), pathogenic (Salmonella typhimurium; Staphylococcus aureus) and eukaryotic (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) microorganisms. Its antifungal activity was also demonstrated against a prevalent species of Candida (Candida albicans) and a filamentous fungus (Aspergillus niger). The minimal inhibitory concentrations for fungi were about 0.25 mg ml−1; PGAIC is thus classified as potent anti-Candida agent (Aligiannis et al., 2001). Owing to the potential of PGA and its derivatives as surface-contact adhesives (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002), PGAIC-coated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) films have been efficiently manufactured. As a result, zones of growth inhibition appeared when PGAIC-coated PETs were placed in culture plates, whereas PET itself had very little effect on fungal growth. Accordingly, solubilized materials of PGAIC show promise as an antimicrobial material and as a coating substrate.

HDP+ is a potent and broadly acting microbicidal agent against bacteria and fungi. The structure of HDP+ comprises a hydrophobic chain (aliphatic alkane) and a hydrophilic ring (pyridinium cation). The hydrophobic chain primarily serves to make initial contact with a cell and subsequently is used to attach to membranes, while the hydrophilic ring increases the permeability of the membrane causing the cytoplasmic contents to leak, resulting in cell death (Hugo and Russell, 1982; Petrocci, 1983; Schep et al., 1995; Jones et al., 1995a,b). PGAIC, however, is formed via multiple ionic bonds between the pyridinium cations of the HDP+ molecules and the carboxyl anions of PGA (Fig. 7), suggesting that it lacks microbicide functions. Furthermore, the rates of dissociation and diffusion of HDP+ from stable PGAIC are limited or very slow, resulting in its resistance to degradation by chemicals. Taken together, these characteristics indicate that PGAIC essentially acts as a microbiostat (non-microbicide).

Prospects and opportunities

Because antibiotics continue to be used inappropriately, the emergence of drug-resistant strains of fungal pathogens is increasing. Candida species, in particular, cause serious health problems and are often associated with life-threatening mycoses (Calderone, 2002; Lass-Flör, 2009). Therefore, the development of high-performance plastic materials possessing antimicrobial activity as well as biodegradability (or biocompatibility) has become a requisite in the food packaging industries (Liu et al., 2009) and for producing advanced pharmaceuticals (Schwartz et al., 2012; Song et al., 2012). Interestingly, PGAIC has the potential to serve as a bio-plastic material possessing a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, resulting from a novel contact-active mechanism of growth inhibition (Ashiuchi et al., 2013a). As a class of antimicrobial agents, polymeric materials are generally more efficient and selective (thus safer) than smaller molecules including elemental silver and its composites (Kenawy et al., 2007), because they can facilitate prolonged activity owing to the controlled release of toxic moieties from the polymer networks. Long-acting microbiostatic polymers may reduce the spread of drug-resistant microbes.

Over the long term, a biotechnological method for the hyper-elongation and mass-production of useful polyamide materials is needed. Eventually, after optimization, it is hoped that the performance of polyamide materials can be dramatically improved so that they are suitable for widespread industrial applications.

References

- Akagi T, Baba M, Akashi M. Preparation of nanoparticles by the self-organization of polymers consisting of hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments: potential applications. Polymer. 2007;48:6729–6747. [Google Scholar]

- Aligiannis N, Kalpotzakis E, Mitaku S, Chinou IB. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of two Origanum species. J Agri Food Chem. 2001;40:4168–4170. doi: 10.1021/jf001494m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aono R. Characterization of structural component of cell walls of alkalophilic strain of Bacillus sp. C-125. Biochem J. 1987;245:467–472. doi: 10.1042/bj2450467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M. Occurrence and biosynthetic mechanism of poly-γ-glutamic acid. In: Hamano Y, editor. Microbiol Monogr (Amino-Acid Homopolymers Occurring in Nature) Vol. 15. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2010. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M. Analytical approaches to poly-γ-glutamate: rapid quantification, molecular size determination, and stereochemistry investigation. J Chromatogr B. 2011;879:3096–3101. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Misono H. Poly-γ-glutamic acid. In: Fahnestock SR, Steinbüchel A, editors. Biopolymers. Vol. 7. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2002. pp. 123–174. (chap. 6) [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Soda K, Misono H. A poly-γ-glutamate synthetic system of Bacillus subtilis IFO 3336: gene cloning and biochemical analysis of poly-γ-glutamate produced by Escherichia coli clone cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263:6–12. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Kamei T, Baek DH, Shin SY, Sung MH, Soda K, et al. Isolation of Bacillus subtilis (chungkookjang), a poly-γ-glutamate producer with high genetic competence. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001a;57:764–769. doi: 10.1007/s00253-001-0848-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Nawa C, Kamei T, Song JJ, Hong SP, Sung MH, et al. Physiological and biochemical characteristics of poly γ-glutamate synthetase complex of Bacillus subtilis. Eur J Biochem. 2001b;268:5321–5328. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Shimanouchi K, Nakamura H, Kamei T, Soda K, Park C, et al. Enzymatic synthesis of high-molecular-mass poly-γ-glutamate and regulation of its stereochemistry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4249–4255. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4249-4255.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Nakamura H, Yamamoto M, Misono H. Novel poly-γ-glutamate-processing enzyme catalyzing γ-glutamyl DD-amidohydrolysis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006;102:60–65. doi: 10.1263/jbb.102.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Fukushima F, Oya H, Hiraoki T, Shibatani S, Oka N, et al. Development of antimicrobial thermoplastic material from archaeal poly-γ-L-glutamate and its nanofabrication. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013a;5:1619–1624. doi: 10.1021/am3032025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Yamamoto T, Kamei T. Pivotal enzyme in glutamate metabolism of poly-γ-glutamate-producing microbes. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 2013b;3:181–188. doi: 10.3390/life3010181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashiuchi M, Yamashiro D, Yamamoto K. Bacillus subtilis EdmS (formerly PgsE) participates in the maintenance of episomes. Plasmid. 2013c doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.03.008. (in press). doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj I, Singhal R. Poly (glutamic acid) – An emerging biopolymer of commercial interest. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:5551–5561. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya D, Hestekin JA, Brushaber P, Cullen L, Bachas LG, Sikder SK. Novel poly-glutamic acid functionalized microfiltration membranes for sorption of heavy metals at high capacity. J Membr Sci. 1998;141:121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Birrer GA, Cromwick AM, Gross RA. γ-Poly(glutamic acid) formation by Bacillus licheniformis 9945A: physiological and biochemical studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 1994;16:265–275. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderone R. Introduction and historical perspectives. In: Calderone R, editor. Candida and Candidiasis. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 2002. pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Candela T, Fouet A. Poly-gamma-glutamate in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1091–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candela T, Moya M, Haustant M, Fouet A. Fusobacterium nucleatum, the first Gram-negative bacterium demonstrated to produce polyglutamate. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55:627–632. doi: 10.1139/w09-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Asada Y, Aida T. Production of γ-polyglutamic acid by Bacillus subtilis A35 under denitrifying conditions. Agric Biol Chem. 1989;53:2369–2375. [Google Scholar]

- Choi HJ, Kunioka M. Preparation conditions and swelling equilibria of hydrogel prepared by γ-irradiation from microbial poly γ-glutamic acid. Radiat Phys Chem. 1995;46:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cromwick AM, Gross RA. Effect of manganese (II) on Bacillus licheniformis ATCC9945A: physiology and γ-poly(glutamic acid)formation. Int J Biol Macromol. 1995;17:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(95)98153-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearfield KL, Abermathy CO. Acrylamide: its metabolism, development and reproductive effects, genotoxicity, and carcinogenicity. Mutant Res. 1988;195:45–77. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(88)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekie L, Toncheve V, Dubruel P, Schacht EH, Baarrett L, Seymour LW. Poly-l-glutamic acid derivatives as vectors for gene therapy. J Control Release. 2000;65:187–202. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger M, Bunk B, Johns MA, Edirisinghe JN, Kutumbaka KK, Koenig SSK, et al. Genome sequences of the biotechnologically important Bacillus megaterium strains QM B1551 and DSM319. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4199–4213. doi: 10.1128/JB.00449-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eveland SS, Pompliano DL, Anderson MS. Conditionally lethal Escherichia coli murein mutants contain point defects that map tp regions conserved among murein and folyl poly-γ-glutamate ligases: identification of a ligase superfamily. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1997;36:6223–6229. doi: 10.1021/bi9701078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Moews PC, Shi Y, Walsh CT, Knox JR. A common fold for peptide synthetases cleaving ATP to ADP: glutathione synthetase and d-alanine:d-alanine ligase of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1172–1176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Koonin EV. A diverse superfamily of enzymes with ATP-dependent carboxylate-amine/thiol ligase activity. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2639–2643. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He LM, Neu MP, Vanderberg LA. Bacillus licheniformis γ-glutamyl exopolymer: physicochemical characterization and U (VI) interaction. Environ Sci Technol. 2000;34:1694–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Hezayen FF, Rehm BHA, Tindall BJ, Steinbüchel A. Transfer of Natrialba asiatica B1T to Natrialba taiwanensis sp. nov., a novel extremely halophilic, aerobic, non-pigmented member of the Archaea from Egypt that produces extracellular poly(glutamic acid) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:1133–1142. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-3-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo WB, Russell AD. Types of antimicrobial agents. In: Russell AD, Hugo WB, Ayliffe GAJ, editors. Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publication; 1982. pp. 158–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Tanaka T, Ohmachi T, Asada Y. Glutamic acid independent production of poly(g-glutamic acid) by Bacillus subtilis TAM-4. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:1239–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DS, Schep LJ, Shepherd MG. The effect of cetylpyridinium chloride on the cell surface charge (zeta potential) of Candida albicans: implications for anti-adherence effects. Pham Sci. 1995a;1:513–515. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DS, Schep LJ, Shepherd MG. The effect of cetylpyridinium chloride on the cell surface hydrophobicity and adherence of Candida albicans to human buccal epithelial cells in vitro. Pham Res. 1995b;12:1896–1900. doi: 10.1023/a:1016231620470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambourova M, Tangney M, Priest FG. Regulation of polyglutamic acid synthesis by glutamate in Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1004–1007. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.1004-1007.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapatral V, Anderson I, Ivanova N, Reznik G, Los T, Lykidis A, et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the oral bacterium Fusobacterium nucleatum strain ATCC 25586. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2005–2018. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.2005-2018.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenawy ER, Worley SD, Broughton R. The chemistry and applications of antimicrobial polymers: a state-of-the-art review. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1359–1384. doi: 10.1021/bm061150q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppie J, Harris-Smith PW, Smith H. The chemical basis of the virulence of Bacillus anthracis. IX. Its aggressins and their mode of action. Br J Exp Pathol. 1963;44:446–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Kim TK, Graham NB. Controlled release behavior of prodrugs based on the biodegradable poly(L-glutamic acid) microspheres. Polym J. 1999;31:813–816. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnersley A, Strom D, Meah RY, Koskan CP. 1994. Composition and method for enhanced fertilizer uptake by plants (WO patent no. 94/09,628)

- Kino K, Kotanaka Y, Arai T, Yagasaki M. A novel L-amino acid ligase from Bacillus subtilis NBRC3134, a microorganism producing peptide-antibiotic rhizocticin. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:901–907. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida A, Murakami K, Goto H, Akashi M. Polymer drugs and polymeric drugs. X. Slow release of 5-fluorouracil from biodegradable poly(γ-glutamic acid) and its benzyl ester matrices. J Bioact Compat Polym. 1998;13:270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kocianova S, Vuong C, Yao Y, Voyich JM, Fischer ER, DeLeo FR, et al. Key role of poly-γ-DL-glutamic acid in immune evasion and virulence of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:688–694. doi: 10.1172/JCI23523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota H, Matsunobu T, Uotani K, Takebe H, Satoh A, Tanaka T, et al. Production of poly(γ-glutamic acid) by Bacillus subtilis F-2-01. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1212–1213. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunioka M, Goto A. Biosynthesis of poly(γ-glutamic acid) from L-glutamic acid, citric acid, and ammonium sulfate in Bacillus subtilis IFO3335. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;40:867–872. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini AM, Alloni G, Azevedo V, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass-Flör L. The changing face of epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in Europe. Mycoses. 2009;52:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NH, Frank CW. Separation of chiral molecules using polypeptide-modified poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes. Polymer. 2002;43:6255–6262. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CG, Housewright RD. Polyglutamic acid synthesis by cell-free extracts of Bacillus licheniformis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963;73:530–532. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(63)90461-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Price JE, Milas L, Hunter NR, Ke S, Tansey W, et al. Antitumor activity of poly(L-glutamic acid)-paclitaxel on syngeneic and xenografted tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:891–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Jin TN, Coffin DR, Hicks KB. Preparation of antimicrobial membranes: coextrusion of poly(lactic acid) and nisaplin in the presence of plasticizers. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:8392–8398. doi: 10.1021/jf902213w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuiki M, Mizuo A, Tanimoto H, Motoki M. Relationship between the antifreeze activities and the chemical structures of oligo- and poly(glutamic acid)s. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:891–895. [Google Scholar]

- Niemetz R, Kärcher U, Kandlera O, Tindall BJ, König H. The cell wall polymer of the extremely halophilic archaeon, Natronococcus occultus. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:905–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Yamaguchi F, Yuasa K, Tahara Y. Efficient production of γ-polyglutamic acid by Bacillus subtilisnatto) in jar fermenters. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:1684–1687. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani Y, Tabata Y, Ikeda Y. Hemostatic capability of rapidly curable from gelatin, poly(L-glutamic acid), and carbodiimide. Biomaterials. 1998;19:2091–2098. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Choi JC, Choi YH, Nakamura H, Shimanouchi K, Horiuchi T, et al. Synthesis of super-high-molecular-weight poly-γ-glutamate from Bacillus subtilis subsp. chungkookjang. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2005;35:128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Camero G, Congregado F, Bou JJ, Muñoz-Guerra S. Biosynthesis and ultlasonic degradation of bacterial poly(γ-glutamic acid) Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;63:110–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrocci AN. Surface-active agents: quaternary ammonium compounds. In: Block SS, editor. Disinfection, Sterilization and Preservation. 3rd edn. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Lea and Febiger; 1983. pp. 309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Pötter M, Oppermann-Sanio FB, Steinbüchel A. Cultivation of bacteria producing polyamino acids with liquid manure as carbon and nitrogen source. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:617–622. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.617-622.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prencipe G, Tabakman SM, Welsher K, Liu Z, Goodwin AP, Zhang L, et al. PEG branched polymer for functionalization of nanomaterials with ultralong blood circulation. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4783–4787. doi: 10.1021/ja809086q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price PA. Vitamin K-dependent formation of bone Gla protein (osteocalcin) and its function. Vitam Horm. 1985;42:65–108. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)60061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read TD, Peterson SN, Tourasse N, Baillie LW, Ian T, Paulsen IT, et al. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature. 2003;423:81–86. doi: 10.1038/nature01586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowinsky KE, Donehower RC. Paclitaxel (Taxol) N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1004–1014. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504133321507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura S. On Bacillus natto. J Coll Agric. 1913;5:189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Schep LJ, Jones DS, Shepherd MG. Primary interactions of three quaternary ammonium compounds with blastospores of Candida albicans (MEN strain) Pham Res. 1995;12:649–652. doi: 10.1023/a:1016291021552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz VB, Thétiot F, Ritz S, Pütz S, Choritz L, Lappas A, et al. Antibacterial surface coatings from zinc oxide nanoparticles embedded in poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogel surface layers. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:2376–2386. [Google Scholar]

- Sekine T, Nakamura T, Shimizu Y, Ueda H, Matsumoto K, Takimoto Y, et al. A new type of surgical adhesive made from porcine collagen and polyglutamic acid. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;35:305–310. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200102)54:2<305::aid-jbm18>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Y, Sun X, Shen Y, Bognar AL, Baker EN, Smith CA. Structural and functional similarities in the ADP-forming amide bond ligase superfamily: implications for a substrate-induced conformational change in folylpolyglutamate synthetase. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:427–440. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih IL, Van YT. The production of poly-(γ-glutamic acid) from microorganisms and its various applications. Bioresour Technol. 2001;79:207–225. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(01)00074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih IL, Van YT, Yeh LC, Lin HG, Chang YN. Production of a biopolymer flocculant from Bacillus licheniformis and its flocculation properties. Bioresour Technol. 2001;78:267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(01)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Nakamura H, Ashiuchi M. Salt-inducible bionylon polymer from Bacillus megaterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:2378–2379. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02686-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Kang H, Lee C, Hwang SH, Jang J. Aqueous synthesis of silver nanoparticle embedded cationic polymer nanofibers and their antibacterial activity. Appl Mater Interfaces. 2012;4:460–465. doi: 10.1021/am201563t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spotniz WD. Hemostats, sealants, and adhesives: a practical guide for the surgeon. Am Surg. 2012;78:1305–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachaboonyakiat W, Serizawa T, Endo T, Akashi M. The influence of molecular weight over the ultrathin films of biodegradable polyion complexes between chitosan and poly(γ-glutamic acid) Polym J. 2000;32:481–485. [Google Scholar]

- Takami H, Nakasone K, Takaki Y, Maeno G, Sasaki R, Masui N, et al. Complete genome sequence of the alkaliphilic bacterium Bacillus halodurans and genomic sequence comparison with Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4317–4331. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto H, Mori M, Motoki M, Torii K, Kadowaki M, Noguchi T. Natto mucilage containing poly-γ-glutamic acid increases soluble calcium in the rat small intestine. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65:516–521. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne CB, Gómez CG, Noyes HE, Housewright RD. Production of glutamyl polypeptide by Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1954;68:307–315. doi: 10.1128/jb.68.3.307-315.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushibata Y, Tokuyama S, Tahara Y. Characterization of the Bacillus subtilis ywsC gene, involved in γ-polyglutamic acid production. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:337–343. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.337-343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Yang G, Che C, Liu Y. Heterogenous expression of poly-γ-glutamic acid synthetase complex gene of Bacillus licheniformis WBL-3. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2011;47:381–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Cao X, Shen M, Guo R, Bányal I, Shi X. Fabrication and morphology control of electrospun poly(γ-glutamic acid) nanofibers for biomedical applications. Colloids Surf B. 2012;89:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber J. Nematocysts (stinging capsules of Cnidaria) as Donnan-potential-dominated osmotic systems. Eur J Biochem. 1989;184:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber J. Poly(γ-glutamic acid)s are the major constituents of Nematocysts in HydraHydrozoaCnidaria. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9664–9669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahata K, Sadanobu J, Endo T. Preparation of poly-α-benzyl-γ-polyglutamate fiber. Polym Prep Jpn. 1992;41:1077. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki D, Minouchi Y, Ashiuchi M. Extremolyte-like applicability of an archaeal exopolymer, poly-γ-L-glutamate. Environ Technol. 2010;31:1129–1134. doi: 10.1080/09593331003592279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro D, Yoshioka M, Ashiuchi M. Bacillus subtilis pgsE (formerly ywtC) stimulates poly-γ-glutamate production in the presence of zinc. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:226–230. doi: 10.1002/bit.22913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yangtse W, Zhou Y, Lei Y, Qiu Y, Wei X, Ji Z, et al. Genome sequence of Bacillus licheniformis WX-02. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3561–3562. doi: 10.1128/JB.00572-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi H, Natsuda O, Hirose J, Hayashi S, Takasaki Y. Characteristics of a biopolymer flocculant produced by Bacillus sp. PY-90. J Ferment Bioeng. 1995;79:378–380. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi H, Arima T, Hirose J, Hayashi S, Takasaki Y. Flocculation properties of poly(γ-glutamic acid) produced by Bacillus subtilis. J Ferment Bioeng. 1996;82:84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Ren SX, Li HL, Wang YX, Fu G, Yang J, et al. Genome-based analysis of virulence genes in a non-biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis strain (ATCC 12228) Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1577–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]