To the Editor

Rhinosinusitis (RS) is among the most common conditions encountered in medicine, affecting approximately 15% of the adult population annually.1, 2 According to major consensus guidelines, antibiotics are not recommended for most patients with uncomplicated cases of acute RS (ARS).1–5 The role of antibiotics for chronic RS (CRS) is controversial,2 and recent authors recommend objective evidence by endoscopy or CT should be obtained if a prolonged course of antibiotics are to be given for CRS.6 However, previous studies show antibiotics are prescribed extensively to treat RS, in approximately over 80% of ARS7 and 50% of CRS8 patient visits.

Excessive antibiotic use is associated with consequences including allergic reactions, adverse effects, unnecessary costs, and increasing bacterial resistance. With the clinical and economic tolls of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in mind, the goal of this study was to perform a contemporary analysis of the overall antibiotic burden of RS on a national level.

We analyzed data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) Outpatient Department component from 2006–2010. These surveys are conducted annually by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to provide data from a national sample of outpatient visits. These data are weighted to produce national estimates that describe the utilization of ambulatory medical care services in the United States.

We identified visits by adults 18 years of age or older in which an antibiotic was prescribed (antibiotic visits). The total number and percentage of primary diagnoses, identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code, associated with each antibiotic visit were tabulated. Primary diagnoses commonly grouped together9 were also analyzed in groups. The number and percentage of antibiotic visits associated with a primary diagnosis of ARS (ICD-9-CM 461.x) and CRS (ICD-9-CM 471.x or 473.x) were tabulated. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (Version 12.0.; STATA Corp, College Station, TX). Descriptive data are presented as mean with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Accounting for the survey’s sampling design, statistics were derived by a multistage estimation procedure designed by the National Center for Health Statistics to produce essentially unbiased national estimates: 1) inflation by reciprocals of the probabilities of selection, 2) adjustment for nonresponse, 3) a ratio adjustment to fixed totals, and 4) weight smoothing.10

Over the five year study period, there were 21.4 million [95% confidence interval (CI), 17.2–25.7 million] estimated visits associated with a primary diagnosis of ARS, and 47.9 million [95% CI, 41.2–54.7 million] estimated visits associated with a primary diagnosis of CRS. Overall, antibiotics were prescribed in 85.5% [95% CI, 80.7–89.2%] of ARS visits and 69.3% [95% CI, 64.8–73.5%] of CRS visits.

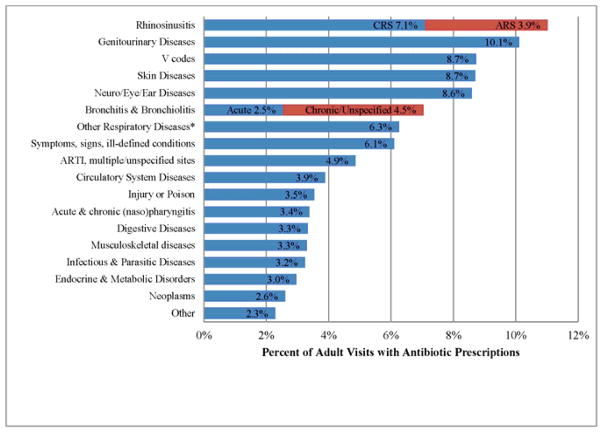

Over the five year study period, RS (ARS and CRS combined) accounted for 11.0% [95% CI, 10.0–12.1%] of all primary diagnoses for ambulatory care visits with antibiotic prescriptions, more than any other diagnosis or commonly grouped diagnoses (Figure 1). When comparing individual diagnoses, a primary diagnosis of unspecified CRS (ICD-9 473.x) accounted for 7.1% [95% CI, 6.2–8.0%] of antibiotic visits, still more than any other primary diagnosis. Analyses by individual year are presented in Table 1. There was no significant linear time trend in overall antibiotic burden in RS groups (p=0.98 for all RS, p=0.16 for CRS, p=0.19 for ARS). Because CRS with nasal polyps may be coded as 473.x (CRS) and 471.x (nasal polyp), we have shown that a diagnosis of nasal polyp did not make a meaningful contribution to the overall antibiotic burden of RS (Table 1). In 2010, unspecified CRS (ICD-9 473.x) accounted for 5.57% of antibiotic visits and ranked second to unspecified urinary tract infection, which accounted for 5.59% of antibiotic visits.

Figure 1.

Primary Diagnoses for Adult Outpatient Visits Resulting in Antibiotic Prescriptions

Abbreviations: CRS=Chronic Rhinosinusitis, ARS=Acute Rhinosinusitis, ARTI=Acute Respiratory Infection

* Tonsillitis/adenoiditis, laryngitis/tracheitis, deviated septum, peritonsillar abscess, allergic rhinitis, adenoid/tonsil hypertrophy/vegetations, pneumonia, influenza, emphysema, asthma, bronchiectasis, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, chronic airways obstruction NOS, pneumoconiosis, pleurisy, pneumothorax, lung/mediastinal abscess, pulmonary congestion/hypostasis, post-inflammatory pulmonary fibrosis, other alveolar diseases, other parieto/pneumopathies, sclerotic lung disease, acute chest syndrome, lung involvement in other disorders, other respiratory diseases

Table 1.

Percent of Outpatient Visits with Antibiotic Prescriptions Attributed to RS Diagnoses

| RS Total % (Rank*) | CRS % (Rank*) | ARS | Nasal Polyps | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 11.6 (1) | 7.8 (1) | 3.7 | 0.06 |

| 2007 | 9.6 (1) | 7.1 (1) | 2.5 | <0.01 |

| 2008 | 12.2 (1) | 8.2 (1) | 4.0 | 0.03 |

| 2009 | 10.7 (1) | 6.9 (1) | 3.7 | 0.03 |

| 2010 | 11.0 (1) | 5.6 (2) | 5.4 | 0.01 |

| Combined years, 2006–2010 | 11.0 (1) | 7.1 (1) | 3.9 | 0.03 |

Rank among all primary diagnoses or commonly grouped diagnoses for receipt of an antibiotic

The most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes at CRS visits were penicillins/beta-lactams, followed by macrolides, then quinolones (33.0% [95% CI, 26.3–41.2]%, 25.6% [95% CI, 21.3–30.4]%, and 18.6% [95% CI, 15.0–22.8]%, respectively). The most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes at ARS visits were penicillins/beta-lactams, followed by macrolides, then quinolones (54.4% [95% CI, 39.5–73.7]%, 28.7% [95% CI, 22.7–35.4]%, 19.9% [95% CI, 15.7–25.0]%, respectively).

This study demonstrates that RS accounts for more outpatient antibiotic prescriptions than any other diagnosis, identifying RS as a major target in national efforts to reduce unnecessary medical intervention. The proportion of outpatient antibiotics attributed to RS did not decrease following release of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head&Neck Surgery Clinical Practice Guidelines released in September 2007 (Table 1).3 In 2010, the proportion of all antibiotics associated with CRS diagnosis 473.x dropped, but the ARS diagnosis increased; future data will tell whether these changes represent fluctuations or a trend.

A study published in 1995 by McCaig and Hughs9 identified sinusitis as the fifth most common diagnosis associated with antibiotic prescriptions, and this figure is cited frequently in mass media and scientific literature, including major consensus guidelines1, 3. Their study used NAMCS data, but differs from our study as it included children and excluded fluoroquinolones, and macrolides.9 The increased burden of antibiotics accounted for by RS in our study likely reflects these differences in methodology, but may also reflect reduced antibiotic utilization for other diagnoses and reflexive increase in the proportion of antibiotics attributed to RS; such a determination is outside the scope of this study.

Physicians prescribed antibiotics in the vast majority of ARS and CRS visits in this study. Major consensus guidelines recommend against antibiotic treatment for uncomplicated mild ARS,1–5 and the role of antibiotics in CRS is controversial.2 According to the 2005 JTFPP guidelines, antibiotics may be useful for acute exacerbation of chronic disease.2 However, there are no placebo-controlled trials regarding short-term antibiotic treatment of CRS without nasal polyps, but there is some evidence supporting long-term, low-dose macrolide antibiotics for 12 weeks for patients with CRS.1 The 2012 European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps guidelines recommend initial long term macrolide therapy for moderate/severe cases of CRS without NP. In our study, CRS was associated most frequently with penicillins/beta-lactams, followed by macrolides. Lee and Bhattacharyya showed that amoxicillin and azithromycin were the most commonly prescribed antibiotics for CRS diagnoses in 2005–2006, with variations by region and physician specialty.8 Those authors propose that a lack of evidence regarding CRS treatment may lead physicians to broadly prescribe medications without improving patient care or outcomes.8 Ferguson et al. suggest that objective evidence by endoscopy or CT should be obtained if antibiotics are to be given for prolonged duration, recommending a “moratorium for the widespread practice of a prolonged course of empiric antibiotics in patients with presumed CRS.” 6 Nevertheless, it is apparent that antibiotics are prescribed frequently for ARS and CRS.

Our study relies on ICD-9 coding in a national database, and limitations include inability to reliably parse acute from chronic RS, and acute and chronic bronchitis. Therefore, we present data based on individual ICD-9 codes, as well as combined codes for all forms of RS and forms of bronchitis (Figure 1). Inclusion of ARS along with CRS ICD-9 diagnoses assures capture of all RS visits, including acute exacerbations of CRS that may be coded as ARS.

Failure to adhere to recommended antibiotic treatment guidelines remains a significant issue in RS. Thus, current treatment recommendations should be promoted across specialties, and efforts to educate policymakers and the general public on the indications, benefits, and risks of antibiotics should be increased. This should be of high relevance to policy makers, patients, and clinicians.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Research for this paper was done in large part while Dr. Stephanie Shintani Smith was a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Studies, supported by an institutional award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, T-32 HS 000078 (PI: Jane L. Holl, MD MPH), and while Dr. Sean Smith was supported by an NIH/NHLBI training grant T-32 HL 076139 (PI: Jacob Sznajder, MD).

We thank Jane Holl, MD, director of the postdoctoral fellowship in Health Services Research and Min-Woong Sohn who provided statistical support, at the Northwestern University Institute for Healthcare Studies. None of the persons listed received compensation for their contributions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. Rhinology. 2012;50:1–307. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL, Kaliner MA, Kennedy DW, Virant FS, et al. The diagnosis and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:S13–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Allergy A, & Immunology. Choosing Wisely: Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, Brozek JL, Goldstein EJ, Hicks LA, et al. IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis in Children and Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e72–e112. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson BJ, Narita M, Yu VL, Wagener MM, Gwaltney JM., Jr Prospective observational study of chronic rhinosinusitis: environmental triggers and antibiotic implications. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:62–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SS, Kern RC, Chandra RK, Tan BK, Evans CT. Variations in Antibiotic Prescribing of Acute Rhinosinusitis in United States Ambulatory Settings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0194599813479768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee LN, Bhattacharyya N. Regional and specialty variations in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1092–7. doi: 10.1002/lary.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCaig LF, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial drug prescribing among office-based physicians in the United States. JAMA. 1995;273:214–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics. NAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. Hyattsville, Md: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]